Abstract

Background

The Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is an inherited rare cancer predisposition syndrome characterized by a variety of early-onset tumors. Although germline mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53 account for over 50% of the families matching LFS criteria, the lack of TP53 mutation in a significant proportion of LFS families, suggests that other types of inherited alterations must contribute to their cancer susceptibility. Recently, increases in copy number variation (CNV) have been reported in LFS individuals, and are also postulated to contribute to LFS phenotypic variability.

Methods

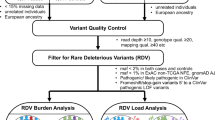

Seventy probands from families fulfilling clinical criteria for either Li-Fraumeni or Li-Fraumeni-like (LFS/LFL) syndromes and negative for TP53 mutations were screened for germline CNVs.

Results

We found a significantly increased number of rare CNVs, which were smaller in size and presented higher gene density compared to the control group. These data were similar to the findings we reported previously on a cohort of patients with germline TP53 mutations, showing that LFS/LFL patients, regardless of their TP53 status, also share similar CNV profiles.

Conclusion

These results, in conjunction with our previous analyses, suggest that both TP53-negative and positive LFS/LFL patients present a broad spectrum of germline genetic alterations affecting multiple loci, and that the genetic basis of LFS/LFL predisposition or penetrance in many cases might reside in germline transmission of CNVs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is an inherited condition characterized by early-onset sarcoma, brain, breast and other cancers. Families with incomplete LFS features are referred to as Li-Fraumeni-like (LFL) [1, 2]. Germline mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53 account for over 50% of the families matching LFS criteria [3] but for only 20-40% of the LFL families [4]; lack of TP53 mutation in a significant proportion of LFS/LFL families, suggests that other types of inherited alterations must contribute to their cancer susceptibility. Although point mutations have been commonly described, DNA copy number variations (CNVs) have been reported as an alternative mechanism for cancer predisposition for at least 30% of known Mendelian cancer genes [5, 6], including TP53[7, 8], APC[9], BRCA1[10] and the mismatch repair gene MSH2[9].

We used microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (array-CGH) to screen for CNVs in the germline DNA of 70 patients fulfilling diagnostic criteria for LFS or LFL, but with no detectable mutation involving TP53[11]. Results were compared to a random sample of 100 Brazilian control individuals [12], to a sample of LFS/LFL TP53 mutated patients previously published by us [13], and to publically available CNV data in normal individuals (DGV).

Subjects and methods

Patients

The patients were recruited and ascertained at the Department of Oncogenetics of the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, Brazil. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the institution and informed consent obtained from all subjects and their families. DNA was isolated from peripheral leukocytes using standard protocols. The cohort comprised 70 non-related probands fulfilling either the classical definition of LFS or at least one of the clinical criteria commonly defining LFL (Chompret, Birch or Eeles’s definitions) [14–17]. These DNA samples had been previously shown to have no mutations in the coding sequences (exons 2 to 11) or splice junctions of the TP53 gene [18].

Controls

The CNV data of a group of 100 individuals randomly selected from the urban area of São Paulo, Brazil, was used as control for this study as previously described [12].

Array-CGH

Array-CGH was performed using a 180 K whole-genome platform (design 22060, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA), with an average spacing of 18 Kb between probes. Scanned images of the arrays were processed and analyzed using Feature Extraction software and Genomic Workbench software (both from Agilent Technologies), together with the statistical algorithm ADM-2, and using a sensitivity threshold of 6.7. We applied a ‘loop design’ in our hybridizations as previously described [19], resulting in two reverse labeling hybridizations per sample. Alterations had to encompass at least three consecutive probes with aberrant log2 values to be called by the software, and those not detected in both dye-swap experiments were excluded from the analysis.

Analysis

The detected copy number variations were compared to CNVs reported in the Database of Genomic Variants (DGV; http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home; freeze December, 2011). We arbitrarily classified CNVs into “rare” and “common” by considering as “rare” those CNVs encompassing coding sequences and present in frequencies < 0.1% in DGV, that does not exclude that some rare CNVs might contain smaller segments which can vary in copy number in the population. Mann–Whitney and Fisher-exact tests were used to compare patients and controls for frequency, gene density and size distribution of CNVs.

Gene annotation was performed using the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser (UCSC) and the Catalog of Somatic Mutations (COSMIC; http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/).

Results

The clinical classification of the patients, description of their cancer types and age at onset are given in Additional file 1: Table S1. A total of 567 CNVs were identified in the 70 patients investigated (308 losses and 259 gains). Table 1 presents the CNV features detected in the LFS/LFL patients without TP53 mutations, the previously published CNV data from LFS/LFL patients with mutation [13] and controls. Full CNV data are presented in Additional file 2: Table S2.

No significant differences were found between the TP53- negative patients compared to controls regarding the number of common CNVs per genome or ratio of losses to gains. However, there was a significantly higher number of rare CNVs per genome in this patient group (p = 0.014; Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 1A). With respect to CNV size, the CNVs in the TP53- negative patients were significantly smaller than controls both for common (Figure 1B) and rare (Figure 1C) CNVs (p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney test).

Furthermore, the mean number of genes encompassed by rare alterations per Mb (gene density) was much higher in patients with 31 genes per Mb as opposed to 9 in controls (p < 0.0001; Mann Whitney test) (Figure 1D).

In addition, while no recurrence was found among the rare CNVs in control individuals, 4 rare CNV regions were either recurrent or partially overlapping in 2 independent patients for each region (Table 2).

Discussion

Despite extensive search for other genes underlying LFS/LFL, no genes other than TP53 have been consistently associated with this complex syndrome. However, patient series in the US and Europe have shown that only ~ 30% of those subjects tested for TP53 mutation because of familial predisposition or early-onset of cancer turned out to be positive. This strongly suggests that genetic factors other than TP53 mutations must be contributing to familial predisposition cancer in many LFS/LFL subjects.

We previously described an increased number of CNVs in Brazilian Li-Fraumeni patients carrying germline mutations in the TP53 gene, and also reported an increased number of rare CNVs per genome in patients carrying mutations that affected the DNA binding domain (DBD) of the TP53 gene compared to both controls and p.R337H mutants [13]. The Brazilian founder mutation p.R337H has a markedly less severe impact on tumor predisposition [20, 21] and has a CNV profile much closer to controls than the TP53 DBD mutations [13]. A similar, but milder increase in number of rare CNVs was observed among non-mutated patients. In a previous article [13], we speculated that an increase of rare CNVs could result from inefficient selection against pathogenic CNVs, due to failure or reduction in apoptosis driven by TP53 germline mutations. Similarly, in this new study of TP53- negative patients, increases in the number of rare CNVs could result from mutations in genes other than TP53, possibly in the TP53 pathway, as previously suggested [22–24]. Such an example was recently reported by us [25] in a patient of the present cohort and involved the deletion of the full BAX gene, which is directly activated by the TP53 protein. The very high gene content of rare CNVs in TP53-negative patients (an almost four-fold increase compared to controls) suggests that these CNVs are under strong selective pressure, and that their gene content likely contribute to oncogenesis. Interestingly, TP53-mutated patients also exhibit increased gene density, although this phenomenon is much less striking than in the non-mutated patients (Table 1). These results show that LFS/LFL patient’s, with the exception of those carrying the p.R337H mutation, share similar CNV profiles regardless of their mutation status.

The recurrent regions detected in the rare CNVs in our study encompass several genes with potential functional relevance to carcinogenesis, including MAD1L1, DOT1L1, MAGEA8 and MAGEA9. MAD1L1 encodes a protein that plays an important role in maintaining spindle checkpoint functions and alterations in this gene have been associated with colon, lung, prostate and breast cancers [26, 27]. The histone methyltransferase DOT1L1 is involved in leukemia [28]. The MAGE gene family encodes proteins only expressed on normal germ cells of the testis but are ectopically expressed in melanomas and in a variety of other common cancer types [29]. Although the frequency of each recurrent region is individually low, as a group, rare CNVs may represent a significant contributor to the etiology of LFS/LFL.

Although the potential role of CNVs as genetic risk factors to cancer predisposition has not yet been fully defined, there is now compelling evidence that cancer-related genes may be encompassed or overlapped by common CNVs. Shlien et al. [30] found a significant enrichment of CNVs in LFS probands; among the genes encompassed by common CNVs, they reported recurrence of a duplication of MLLT4, a target of the RAS pathway. In agreement with this, we also detected common MLLT4 duplications in three of the TP53- negative patients but none in the controls. We have also recently reported a 691 kb recurrent deletion at 7q34 harboring only the PIP and TAS2R39 genes [31] in five patients with high cancer predisposition from different cohorts, including two TP53-negative patients from the present study and one TP53-positive LFS patient. Common cancer CNVs, such as the ones harboring MLLT4 and PIP, most likely confer a minor increase in disease risk that collectively or in association with highly penetrant mutations may cause a substantially elevated risk.

Conclusion

These findings support the hypothesis that in LFS/LFL families not carrying TP53 mutations, cancer predisposition may be caused by a broad spectrum of genetic alterations affecting multiple loci. How CNVs and other genetic modifiers interact and modulate TP53 tumor suppressor activities remain to be determined. Elucidating these mechanisms may hold the key to define evidence-based strategies for counseling using combined risks from TP53 and other variants, including CNVs.

Availability of supporting data

The data set supporting the results of this article is included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- LFS:

-

Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- LFL:

-

Li-Fraumeni like syndrome

- CNV:

-

Copy number variation.

References

Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Mulvihill JJ, Blattner WA, Dreyfus MG, Tucker MA, Miller RW: A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988, 48 (18): 5358-5362.

Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, Evans DG, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Eden OB, Varley JM: Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene. 2001, 20 (34): 4621-4628. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204621.

Malkin D, Li FP, Strong LC, Fraumeni JF, Nelson CE, Kim DH, Kassel J, Gryka MA, Bischoff FZ, Tainsky MA: Germ line p53 mutations in a familial syndrome of breast cancer, sarcomas, and other neoplasms. Science. 1990, 250 (4985): 1233-1238. 10.1126/science.1978757.

Nagy R, Sweet K, Eng C: Highly penetrant hereditary cancer syndromes. Oncogene. 2004, 23 (38): 6445-6470. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207714.

Kuiper RP, Ligtenberg MJ, Hoogerbrugge N, Geurts van Kessel A: Germline copy number variation and cancer risk. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010, 20 (3): 282-289. 10.1016/j.gde.2010.03.005.

Krepischi AC, Pearson PL, Rosenberg C: Germline copy number variations and cancer predisposition. Future Oncol. 2012, 8 (4): 441-450. 10.2217/fon.12.34.

Bougeard G, Brugières L, Chompret A, Gesta P, Charbonnier F, Valent A, Martin C, Raux G, Feunteun J, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Frébourg T: Screening for TP53 rearrangements in families with the Li-Fraumeni syndrome reveals a complete deletion of the TP53 gene. Oncogene. 2003, 22 (6): 840-846. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206155.

Bougeard G, Sesboüé R, Baert-Desurmont S, Vasseur S, Martin C, Tinat J, Brugières L, Chompret A, de Paillerets BB, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Bonaïti-Pellié C, Frébourg T, French LFS Working Group: Molecular basis of the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: an update from the French LFS families. J Med Genet. 2008, 45 (8): 535-538. 10.1136/jmg.2008.057570.

Bunyan DJ, Eccles DM, Sillibourne J, Wilkins E, Thomas NS, Shea-Simonds J, Duncan PJ, Curtis CE, Robinson DO, Harvey JF, Cross NC: Dosage analysis of cancer predisposition genes by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Br J Cancer. 2004, 91 (6): 1155-1159. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602121.

Goncalves A, Ewald IP, Sapienza M, Pinheiro M, Peixoto A, Nobrega AF, Carraro DM, Teixeira MR, Ashton-Prolla P, Achatz MI, Rosenberg C, Krepischi AC: Li-Fraumeni-like syndrome associated with a large BRCA1 intragenic deletion. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12 (1): 237-10.1186/1471-2407-12-237.

Marcel V, Palmero EI, Falagan-Lotsch P, Martel-Planche G, Ashton-Prolla P, Olivier M, Brentani RR, Hainaut P, Achatz MI: TP53 PIN3 and MDM2 SNP309 polymorphisms as genetic modifiers in the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: impact on age at first diagnosis. J Med Genet. 2009, 46 (11): 766-772. 10.1136/jmg.2009.066704.

Krepischi AC, Achatz MI, Santos EM, Costa SS, Lisboa BC, Brentani H, Santos TM, Goncalves A, Nobrega AF, Pearson PL, Vianna-Morgante AM, Carraro DM, Brentani RR, Rosenberg C: Germline DNA copy number variation in familial and early-onset breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14 (1): R24-10.1186/bcr3109.

Silva AG, Achatz IMW, Krepischi AC, Pearson PL, Rosenberg C: Number of rare germline CNVs and TP53 mutation types. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012, 7: 101-10.1186/1750-1172-7-101.

Birch JM, Hartley AL, Tricker KJ, Prosser J, Condie A, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Jones PH, Binchy A, Crowther D, Lane DP, Craft AW, Eden OB, Evans DGR, Thompson E, Mann JR, Martin J, Mitchell ELD, Santibáñez-Koref MF: Prevalence and diversity of constitutional mutations in the p53 gene among 21 Li-Fraumeni families. Cancer Res. 1994, 54: 1298-1304.

Eeles RA: Germline mutations in the TP53 gene. Cancer Surv. 1995, 25: 101-124.

Chompret A, Brugières L, Ronsin M, Gardes M, Dessarps-Freichey F, Abel A, Hua D, Ligot L, Dondon MG, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Frébourg T, Lemerle J, Bonaïti-Pellié C, Feunteun J: P53 germline mutations in childhood cancers and cancer risk for carrier individuals. Br J Cancer. 2000, 82 (12): 1932-1937.

Chompret A, Abel A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Brugiéres L, Pagés S, Feunteun J, Bonaïti-Pellié C: Sensitivity and predictive value of criteria for p53 germline mutation screening. J Med Genet. 2001, 38 (1): 43-47. 10.1136/jmg.38.1.43.

Li FP, Fraumeni JF: Soft-tissue sarcomas, breast cancer, and other neoplasms. A familial syndrome?. Ann Intern Med. 1969, 71 (4): 747-752. 10.7326/0003-4819-71-4-747.

Allemeersch J, Van Vooren S, Hannes F, De Moor B, Vermeesch JR, Moreau Y: An experimental loop design for the detection of constitutional chromosomal aberrations by array CGH. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009, 10: 380-10.1186/1471-2105-10-380.

DiGiammarino EL, Lee AS, Cadwell C, Zhang W, Bothner B, Ribeiro RC, Zambetti G, Kriwacki RW: A novel mechanism of tumorigenesis involving pH-dependent destabilization of a mutant p53 tetramer. Nat Struct Biol. 2002, 9 (1): 12-16. 10.1038/nsb730.

Zambetti GP: The p53 mutation “gradient effect” and its clinical implications. J Cell Physiol. 2007, 213 (2): 370-373. 10.1002/jcp.21217.

Bell DW, Varley JM, Szydlo TE, Kang DH, Wahrer DC, Shannon KE, Lubratovich M, Verselis SJ, Isselbacher KJ, Fraumeni JF, Birch JM, Li FP, Garber JE, Haber DA: Heterozygous germ line hCHK2 mutations in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Science. 1999, 286 (5449): 2528-2531. 10.1126/science.286.5449.2528.

Vahteristo P, Tamminen A, Karvinen P, Eerola H, Eklund C, Aaltonen LA, Blomqvist C, Aittomäki K, Nevanlinna H: p53, CHK2, and CHK1 genes in Finnish families with Li-Fraumeni syndrome: further evidence of CHK2 in inherited cancer predisposition. Cancer Res. 2001, 61 (15): 5718-5722.

Barlow JW, Mous M, Wiley JC, Varley JM, Lozano G, Strong LC, Malkin D: Germ line BAX alterations are infrequent in Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004, 13 (8): 1403-1406.

Silva AG, Lisboa BC, Achatz MI, Carraro DM, da Cunha IW, Pearson PL, Krepischi AC, Rosenberg C: Germline BAX deletion in a patient with melanoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013, 108 (8): 1372-1375. 10.1038/ajg.2013.176.

Tsukasaki K, Miller CW, Greenspun E, Eshaghian S, Kawabata H, Fujimoto T, Tomonaga M, Sawyers C, Said JW, Koeffler HP: Mutations in the mitotic check point gene, MAD1L1, in human cancers. Oncogene. 2001, 20 (25): 3301-3305. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204421.

Guo Y, Zhang X, Yang M, Miao X, Shi Y, Yao J, Tan W, Sun T, Zhao D, Yu D, Liu J, Lin D: Functional evaluation of missense variations in the human MAD1L1 and MAD2L1 genes and their impact on susceptibility to lung cancer. J Med Genet. 2010, 47 (9): 616-622. 10.1136/jmg.2009.074252.

Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA: MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007, 7 (11): 823-833. 10.1038/nrc2253.

Sang M, Wang L, Ding C, Zhou X, Wang B, Lian Y, Shan B: Melanoma-associated antigen genes - an update. Cancer Lett. 2011, 302 (2): 85-90. 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.10.021.

Shlien A, Tabori U, Marshall CR, Pienkowska M, Feuk L, Novokmet A, Nanda S, Druker H, Scherer SW, Malkin D: Excessive genomic DNA copy number variation in the Li-Fraumeni cancer predisposition syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105 (32): 11264-11269. 10.1073/pnas.0802970105.

Silva AG, Krepischi AC, Torrezan GT, Capelli LP, Carraro DM, D’Angelo CS, Koiffmann CP, Zatz M, Naslavsky MS, Masotti C, Otto PA, Achatz MIW, Mills RE, Lee C, Pearson PL, Rosenberg C: Does germ-line deletion of the PIP gene constitute a widespread risk for cancer?. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013, 22: 307-309.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients for their participation to this study. This work was supported by Sao Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP (2009/00898-1 and 2008/57887-9) and The Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq (573589/08-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AGS carried out the molecular genetic studies. AGS and PLP wrote the manuscript. ACVK and CR participated in the design and coordination of the study and helped writing the manuscript. MIWA recruited and selected the patients. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13023_2014_744_MOESM2_ESM.xls

Additional file 2: Table S2: Full CNV data on the 70 probands, rare CNVs in bold-chromosome coordinates given according to Hg18. (XLS 195 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, A.G., Krepischi, A.C., Pearson, P.L. et al. The profile and contribution of rare germline copy number variants to cancer risk in Li-Fraumeni patients negative for TP53 mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9, 63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-63

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-9-63