Abstract

Background

This prospective study was conducted to evaluate inter- and intra-fraction errors in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients undergoing volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) and to thus obtain planning target volume (PTV) margins to effectively guide treatment in the future.

Methods

Fifteen NPC patients scheduled to undergo VMAT were prospectively enrolled in the study. For each patient, three CBCT scans were obtained; one after daily conventional positioning, one after online correction with 2 mm tolerance and one after 1 week of VMAT delivery. The scans were registered to the planning CT to determine the inter- and intra-fraction errors. Patient positioning errors were analyzed for time trends over the course of radiotherapy. PTV margins were calculated from the systematic (Σ) and random (σ) errors.

Results

The average absolute values of the pre-correction, post-correction and intra-fraction errors (in order) were 1.1, 0.6 and 0.4 mm in the medial–lateral (ML) direction, 1.2, 0.7 and 0.5 mm in the superior–inferior (SI) direction and 1.1, 0.7 and 0.5 mm in the anterior–posterior (AP) direction. The corresponding Σ were 1.0–1.4 mm, 0.4–0.5 mm and 0.2–0.4 mm, while the corresponding σ were 0.7–0.8 mm, 0.6–0.7 mm and 0.5–0.6 mm. With time, gradual increases in both the inter- and intra-fraction three-dimensional displacements were observed (P = 0.019 and P = 0.044, respectively). The total PTV margins accounting for pre-correction and intra-fraction errors were 3.4–4.1 mm and those accounting for post-correction and intra-fraction errors were 1.7–2.2 mm.

Conclusions

CBCT is an effective modality to evaluate and improve the accuracy of VMAT in NPC patients. Inter- and intra-fraction three-dimensional displacements increased as a function of time during the course of radiotherapy. In our institution, we recommend a PTV margin of 5 mm for NPC patients undergoing VMAT without CBCT and 3 mm for those treated with rigorous daily CBCT scans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is endemic in some regions of the world, especially Southeast Asia. The annual incidence of NPC in Southern China is between 15 and 50 per 100,000 [1]. NPC is unresectable due to the proximity of the tumor to the skull base, and as it has a high radiosensitivity, radiation therapy (RT) remains the mainstay treatment modality for locoregionally confined disease.

Intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) offers superior dose conformity to tumor targets with a relative sparing of critical organs, and recent studies have confirmed that IMRT has a high efficacy of disease control and improved treatment toxicity profile in NPC patients [2, 3]. IMRT processes such as posture fixation, computed tomography (CT) simulation and target volume delineation inherently introduce geometrical uncertainties. Errors of even a few millimeters may have a significant impact on dosimetry, due to the steep dose gradients between the tumor and critical organs [4, 5]. Hence, to take full advantage of IMRT, it is important to minimize setup error and provide appropriate safety margins around the clinical target volumes (CTVs). To date, few data are available on the quantification of setup error and planning target volume (PTV) margins in NPC patients [5, 6].

Intra-fraction motion is one source of positioning error which contributes to the design of PTV margins, and longer treatment times are associated with a greater risk of intra-fraction motion [7]. Only a small number of studies on intra-fraction patient motion monitored by cone-beam CT (CBCT) have been published [8, 9]. Furthermore, all of these studies reported errors occurring during IMRT, which requires a long beam delivery time. A recently described novel approach for volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) enables IMRT-like dose distributions with shorter treatment times [10, 11]; however, it is unclear how much error occurs during VMAT in NPC patients.

Given the importance of determining the setup error and appropriate PTV expansion for VMAT in NPC patients, we sought to characterize and correct the daily inter-fraction setup errors, as well as the residual errors and intra-fraction errors, using kilovoltage (kV) CBCT. On the basis of the results obtained, we determined appropriate PTV margins with a corresponding formula to account for patient variability during VMAT in NPC patients.

Methods

Patient characteristics

We conducted a prospective study on setup measurement error in our center between October 2010 and October 2011. The protocol was approved by the institution’s Protocol Review Board, and all patients provided written informed consent before participation. Eligible patients for this study included individuals with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic NPC, no metal dentures and undergoing definitive-intent VMAT. All patients were staged according to the 7th American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) staging system. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy and concomitant chemotherapy with a platinum-based protocol were recommended for stage III to IVB NPC patients. The characteristics of the patient cohort are shown in Table 1.

RT simulation and planning

All patients were immobilized using a five-point thermoplastic fixation mask with shoulder fixation (Civco Medical Solutions, Kolona, USA). The target volumes were delineated in accordance with the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements reports 50 and 62. The PTVs and planning organ-at-risk volumes were generated by adding a margin of 3 mm to the respective CTVs and corresponding structures such as the spinal cord and brainstem. The prescribed dose was 70 Gy to the PTV of the gross volume of the primary tumor, 64–66 Gy to the PTV of the nodal gross tumor volume, 60 Gy to the PTV of CTV-1 (i.e., high risk regions), 56 Gy to the PTV of CTV-2 (i.e., low-risk regions) and CTV-N (i.e., neck nodal regions) in 33 fractions. Optimization and dose calculation were performed using the Monaco treatment-planning system (version 2.02, Elekta Medical Systems, Crawley, UK) with a Monte Carlo algorithm. All patients were treated with one fraction daily for 5 days per week. Treatment was delivered on a 6-MV linear accelerator equipped with the PreciseBeam VMAT® linac control system (Elekta Medical Systems).

Image-guided radiotherapy procedure

CBCT imaging

The kV CBCT images were obtained using the Elekta Medical Systems linear accelerator equipped with kV imaging capabilities (Synergy; Elekta Medical Systems). The acquisition parameters were as follows: kVp, 100 kV; nominal milliamperes per frame, 10 mA; nominal milliseconds, 10 ms; kV collimator, s20; kV filter, f0; approximate frames, 361; and total angle, 200. Figure 1 shows the contrast between CBCT images and planning CT images of the nasopharynx and neck in the sagittal, coronal and transverse sections. It is obvious that the CBCT images have the quality needed to perform an accurate image registration with planning CT images.

CBCT guidance protocol

The kV CBCT images were acquired on a daily basis after conventional positioning by aligning the in-room lasers with the marks drawn on the masks. If the translational error was greater than 2 mm in any direction, setup corrections were made by adjusting the patient position through automatically shifting the treatment couch in all three translational dimensions. Then, a second CBCT scan was performed to measure the residual setup error and confirm the accuracy of the automatic correction. If the error was greater than 3° or 5 mm in any direction, the therapists removed and re-fitted the mask on the patient, verifying the correct placement. After VMAT delivery, a final CBCT scan was acquired to assess intra-fraction motion once a week. This imaging schedule was discontinued temporarily if the workload of patient treatment was heavy, or if the CBCT scanner was unavailable on the day of treatment.

CBCT image registration

All of the acquired images were assessed online by the radiation therapists, by registering the CBCT scan to the planning CT scan by automatic bone matching using Elekta Medical Systems XVI software. No manual adjustments were performed. The alignment box for automatic image registration included the target volume and organs at risk (such as the spinal cord and brain stem) and the surrounding bony structures above the C6 vertebrae.

Set-up errors protocol

Setup shifts were defined as the deviations between the CBCT and the planning CT in the medial–lateral (ML), superior–inferior (SI) and anterior–posterior (AP) directions, as well as pitch, roll and yaw. The pre-correction CBCT scan acquired after the in-room setup was used to calculate the initial inter-fraction error. The post-correction CBCT scan acquired after any corrections, or the pre-correction CBCT scan for fractions where the initial setup was within ± 2 mm tolerance, was used to calculate the residual inter-fraction error. The difference between the offset of the post-treatment CBCT and the post-correction CBCT, or the difference between the offset of the post-treatment CBCT and the pre-treatment CBCT of less than 2 mm, was used to calculate intra-fraction error.

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard error of the absolute values of pre-correction, post-correction and intra-fraction errors were calculated. For each patient, the mean (m) and standard deviation (SD) of the daily measurements was calculated. The group mean (M, the mean of all patients’ means), the systematic setup uncertainty (Σ, the standard deviation of M) and the random setup uncertainty (σ, the root mean square of the SD of all patients) were calculated for both inter-fraction and intra-fraction errors [12]. The overall Σ and σ were defined as the square root of the quadratic sum of the inter-fraction and intra-fraction Σ and σ, respectively. To calculate the PTV margins, we followed the geometric margin formula developed by van Herk et al., (2.5 Σ + 0.7 σ), which ensures that the minimum CTV dose is 95% for 90% of patients [13].

We also calculated the three-dimensional (3D) displacement, which was defined as the square root of the quadratic sum of the three components of an error. As inter- and intra-fraction errors may increase as the patient’s weight decreases, we examined the relationship between weight loss and setup errors, and analyzed the time trend of weight loss. We then analyzed the differences in setup errors as a function of time by dividing the RT course into intervals of 11 fractions, which were associated with significant differences in weight. The one-way ANOVA F-test for repeated measurements was used to analyze the changes in the displacement as a function of time for each translational direction, as well as the 3D vector direction. The least significance difference was used to compare the difference in displacements between each time group. The criterion for statistical significance was set at P = 0.05, and P values were based on two-sided tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 16.0 (SPSS, IL, Chicago, USA).

Results

Number of images and CBCT scan time

A total of 596 CBCT images were acquired from the 15 NPC patients, including 352 pre-correction images (71.1% of fractions), 149 post-correction images (30.1% of fractions) and 95 post-treatment images (19.2% of fractions). The median number of images per patient was 39.

The interval between the initial CBCT and post-correction CBCT was 4.2 min (range, 3.1–8.0 min), while the interval between the post-treatment CBCT and post-correction CBCT was 11.8 min (range, 9.3–16.8 min).

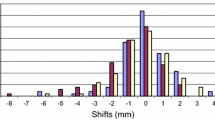

Inter-fraction error

The distribution of inter-fractional setup errors in each of the three translational directions were calculated using the 352 pre-correction images and 149 post-correction images (Figure 2). In all directions, the distributions obtained from the post-correction scans were narrower than those obtained from the pre-treatment scans, all lying within the ±2 mm tolerance level for total treatment fractions. The average absolute values of the pre-correction errors were 1.1, 1.2 and 1.1 mm in the ML, SI and AP directions, respectively, while the corresponding values of post-correction errors were 0.6, 0.7 and 0.7 mm. For initial inter-fractional shifts, the number of fractions exceeding ±2 mm in the ML, SI and AP directions were 57 (16.2%), 64 (18.2%) and 53 (15.1%), respectively, and 22 (6.3%), 51 (14.5%) and 19 (5.4%) fractions exceeded 2° for pitch, roll and yaw, respectively. The residual inter-fraction Σ and σ values were significantly smaller than the initial inter-fraction Σ and σ values (Table 2).

Intra-fraction error

The mean time interval of intra-treatment motion assessment was 7.3 ± 1.2 min (range, 5.6–9.4 min). No significant correlation was observed between the delivery time and the intra-fraction errors in the ML, SI, AP and 3D directions (P = 0.373, 0.523, 0.324 and 0.327, respectively). The mean absolute intra-fraction change was 0.4, 0.5 and 0.5 mm for the ML, SI and AP directions, respectively, while the corresponding values for the pitch, roll and yaw directions were 0.4°, 0.4° and 0.3°, respectively. The number of fractions exceeding ±2 mm in the ML, SI and AP directions were 1 (1.1%), 1 (1.1%) and 4 (4.2%), respectively, and 1 (1.1%), 0 (0.0%) and 0 (0.0%) fractions exceeded 2° for pitch, roll and yaw, respectively. Intra-fraction motion was significantly smaller than the initial inter-fraction error in both the translational and rotational directions (Table 2).

Displacement as a function of time

Our results showed that weight loss was significantly correlated with inter-fraction errors in the ML and 3D directions and with the intra-fraction error in the 3D directions (P < 0.05). The weight decreased significantly when the total treatment time was divided into three equal sections of 11 fractions each (P < 0.05). We, therefore, calculated the mean displacement for each patient after every 11 treatment fractions. The initial inter-fraction errors in the ML and AP directions and the intra-fraction errors in the AP and SI directions gradually increased, but no statistical difference was observed during the treatment period (P = 0.315, 0.065, 0.177 and 0.220, respectively). A gradual increase in the initial inter-fraction and intra-fraction 3D displacements was observed as a function of time (P = 0.019 and P = 0.044, respectively; Figure 3). Further comparisons of displacements in the three time phases indicated that both the initial inter-fraction and intra-fraction 3D displacement values were significantly higher in the last 11 fractions than in the first 11 fractions (2.2 mm vs. 2.5 mm, P = 0.003; 0.8 mm vs. 1.2 mm, P = 0.025).

PTV margins

For all patients, a comparison of the PTV margins obtained from pre-correction, post-correction and post-treatment CBCT images showed that PTV margins can be significantly reduced with the online correction, and margins accounting for intra-fraction errors were smaller than those account for the initial inter-fraction errors (Table 3). The total margins accounting for initial inter-fractional and intra-fractional setup errors were 4.1, 3.4 and 3.5 mm in the ML, SI and AP directions, respectively, in contrast to the corresponding required target margins of only 1.7, 2.2 and 2.2 mm in each of the three directions, if the residual and intra-fraction errors were considered after online correction.

Discussion

CBCT provides a promising method to quantify inter-fraction and intra-fraction errors, and allows a significant reduction in inter-fraction errors. To our knowledge, this is the first report on intra-fraction errors during VMAT in NPC patients, and it provides a guide for designing PTV margins in NPC patients during VMAT.

Inter-fraction error

When applying new treatment techniques to malignancies at other sites, it is necessary to determine setup errors to acquire appropriate PTV margins. The inter-fraction error observed in this study is similar to the inter-fraction error reported by other researches, including the study of Wang et al. in which CBCT analysis indicated that the systematic deviations and random errors during set-up in NPC patients were 1.1–1.3 mm [5]. Similarly, Velec et al. analyzed daily CBCT images acquired during the treatment of 20 head and neck cancer patients, and obtained systematic deviations ranging from 0.8 mm to 1.1 mm and random translational deviations of less than 2 mm [9]. However, a review carried out by Hurkmans et al. focusing on set-up verification in head and neck cancer patients using portal imaging, concluded that the systematic and random deviations varied by 1.6–4.6 mm and 1.1–2.5 mm, respectively [14], which are higher than the values in this study. These differences may be due to the fact that we automatically matched a smaller region of interest confined to the nasopharynx and upper neck, as there is evidence that positional variation is greater in the lower neck than in the upper neck [15]. In addition, our study used rigorous immobilization devices, such as the thermoplastic mask covering the head, neck and shoulders, and such devices have previously been used in IMRT delivery for head and neck cancer to improve the reproducibility and stability of patient position [16].

In our study, CBCT effectively improved the accuracy of VMAT in NPC patients because the inter-fraction systematic error could be decreased from 1.0–1.4 mm to 0.4–0.5 mm, which was similar to the results reported by Wang et al. and Dionisi et al.[5, 17]. While the uncertainties in delivering RT can be reduced with CBCT systems, it is important to understand the uncertainties arising from this process. One of the important factors is the uncertainties in image registration. It is current practice in head and neck cancer to use rigid registrations of bony anatomies with the planning CT, to obtain setup errors. The accuracy of these registrations can be affected by the image dose, image resolution, region of interest used for registration etc.[18–20]. Many research studies have reported bone alignment with an accuracy of nearly 1 mm for the translational displacement of a head phantom [21, 22]. However, head and neck cancer patients experience significant deformation, shrinkage and rotation, all of which could also affect the efficacy of a bone match. Recent studies have shown that due to the considerable and frequent shape and posture changes in patients with head and neck cancer, not all structures within a single large region of interest can be simultaneously aligned using bone registration [23, 24]. Therefore, misregistration can occur and the misalignment can persist due to shape or posture changes. It is encouraging that new registration and correction methods to reduce such misalignment and deformation have been proposed [25, 26]. In future, software updates will be aimed at automating these methods to allow better quantification of the setup error.

Furthermore, due to the limited availability of conventional treatment tables, not all users of the bone registration algorithm can adjust the rotational setup of the patient to minimize setup error [9, 27]. There is a possibility of significant misalignment when only the translational part of a six-dimensional (6D) registration is applied to the patient’s position in a completely general 6D registration framework. Fortunately, strategies for avoiding this misalignment have been proposed by Murphy [28]; these consist of putting the landmark/treatment isocenter at or very near the origin of the rotation axes or calculating only a 3D registration using landmarks near the treatment site. Therefore, it is important to realize the limits of bone registration and deal carefully with the practical application of bone registration tools and patient setup practices during imaging.

Intra-fraction error

Generally, intra-fraction error was mainly influenced by the immobilization device and delivery time. Theoretically, the magnitude and probability of patient intra-fraction movement will most likely increase when fraction times are extended. Hoogeman et al. concluded that intra-fraction systematic geometric error increases with time [7]. However, our study showed that there was no significant correlation between the delivery time and intra-fraction error. One reason for this result was possibly the narrow range of delivery time (5.6–9.4 min), which did not allow statistically significant results to be obtained. Another reason was that limited data were available for analysis, as our study included only 15 patients and six CBCT scans for each patient. In addition, in our study, the intra-fraction systematic error ranged from 0.2 mm to 0.4 mm during the 5–9 min VMAT time. Velec et al. reported an intra-fraction systematic error of 0.3–0.7 mm in patients fixed with a thermoplastic mask covering the head, neck and shoulders during an approximately 15-min IMRT time [9]. A comparison study of IMRT and VMAT in the same institution is required to determine whether VMAT is associated with reduced intra-fraction motion.

Patient intra-treatment movement can be assessed by several methods along a continuum of imaging frequencies. The most commonly used method of assessing intra-treatment motion is pre- and post-treatment imaging [8, 9], which we used in this study. The other approaches are intermittent imaging, acquired as frequently as every 0.5–2 min, or continuous, real-time tracking of the tumor target during radiation delivery with technologies such as CyberKnife or electromagnetic localization [7, 29]. However, as motion may be sustained during the entire course of radiation delivery, differences in the measurement and acquisition schedule could potentially lead to discrepancies between the measured motion and actual motion at radiation delivery. Further studies using continuous imaging should be performed to evaluate the intra-fraction motion during radiation delivery in NPC patients undergoing VMAT.

Gradual increase in displacement as a function of treatment time

Treatment accuracy during fractionated radiotherapy may decrease with time due to tumor regression or weight loss [30]. Den et al. reported that PTV margins in the last 3 weeks were significantly larger than those in the first 3 weeks [27]. We obtained a similar result, as patient inter-fraction and intra-fraction 3D displacements increased gradually as a function of time. Adaptive re-planning strategy is an effective method to account for significant dosimetric variation during radiotherapy, which was mainly caused by setup errors and anatomical changes. Currently, the optimal timing of re-planning remains to be determined.

Appropriate PTV margins

Reasonable designs of PTV margins are the key point for local control and normal tissue protection. Narrow margins tend to be associated with local recurrence, while wide margins result in excessive treatment. Decreasing the PTV margins can theoretically improve the therapeutic gains; such a benefit was illustrated by van Asselen et al.[31], who observed that narrow PTV margins improved parotid sparing and decreased the probability of normal-tissue complications such as xerostomia. However, the application of narrow margins must be based on the premise of excellent quality-control measures such as daily CBCT online correction. In general, narrow margins are not widely used in clinical practice, and are reserved for special cases such as locally advanced tumors that invade tissues adjacent to the brain stem or spinal cord. In this study, we have discussed the PTV margins accounting for setup errors, and these margins were 1.7–2.2 mm and 3.4–4.1 mm with and without correction, respectively. However, it should be noted that PTV margins are not the only component of the setup margin (inter- and intra-fraction motion), and other process-related components such as image registration, treatment planning uncertainties and transfer errors from the planning CT to the simulator should be accounted for. In our institution, therefore, we recommend a PTV margin of 5 mm for NPC patients undergoing VMAT without CBCT and 3 mm for those treated with rigorous daily CBCT scans. Our results provide a theoretical basis for the appropriate design of PTV margins for VMAT in NPC patients.

Conclusions

CBCT is an effective modality to evaluate and improve the accuracy of VMAT in NPC patients. Inter- and intra-fraction 3D displacements increased as a function of time during the course of radiotherapy. In our institution, we recommend a PTV margin of 5 mm for NPC patients undergoing VMAT without CBCT and 3 mm for those treated with rigorous daily CBCT scans.

References

Chan AT, Teo PM, Johnson PJ: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2002, 13: 1007-1015. 10.1093/annonc/mdf179

Lee N, Xia P, Quivey JM, Sultanem K, Poon I, Akazawa C, Akazawa P, Weinberg V, Fu KK: Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an update of the USCF experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002, 53: 12-22. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02724-4

Lin S, Pan J, Han L, Zhang X, Liao X, Lu JJ: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with reduced-volume intensity-modulated therapy: report on the 3-years outcome of a prospective series. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 75: 1071-1078. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.015

Xing L, Lin Z, Donaldson SS, Le QT, Tate D, Goffinet DR, Wolden S, Ma L, Boyer AL: Dosimetric effects of patient displacement and collimator and gantry angle misalignment on intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol 2000, 56: 97-108. 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00192-4

Wang J, Bai S, Chen N, Xu F, Jiang X, Li Y, Xu Q, Shen Y, Zhang H, Gong Y, Zhong R, Jiang Q: The clinical feasibility and effect of online cone beam computer tomography-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal cancer. Radiother Oncol 2009, 90: 221-217. 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.08.017

Mongioj V, Orlandi E, Palazzi M, Deponti E, Marzia F, Stucchi C, Sangalli C, Fallai C, Zonca G, Olmi P, Pignoli E: Set-up errors analyses in IMRT treatments for nasopharyngeal carcinoma to evaluate time trends, PTV and PRV margins. Acta Oncol 2011, 50: 61-71.

Hoogeman MS, Nuyttens JJ, Levendag PC, Heijmen BJ: Time dependence of intrafraction patient motion assessed by repeat stereoscopic imaging. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys 2008, 70: 609-618. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.08.066

Xu F, Wang J, Bai S, Li Y, Shen Y, Zhong R, Jiang X, Xu Q: Detection of intrafractional tumour position error in radiotherapy utilizing cone beam computed tomography. Radiother Oncol 2008,89(3):311-319. 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.08.003

Velec M, Waldron JN, O'Sullivan B, Bayley A, Cummings B, Kim JJ, Ringash J, Breen SL, Lockwood GA, Dawson LA: Cone-beam CT assessment of interfraction and intrafraction setup error of two head-and-neck cancer thermoplastic masks. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010, 76: 949-955. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.004

Otto K: Volumetric modulated arc therapy: IMRT in a single gantry arc. Med Phys 2008,35(1):310-317. 10.1118/1.2818738

Vanetti E, Clivio A, Nicolini G, Fogliata A, Ghosh-Laskar S, Agarwal JP, Upreti RR, Budrukkar A, Murthy V, Deshpande DD, Shrivastava SK, Dinshaw KA, Cozzi L: Volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy for carcinomas of the oro-pharynx, hypo-pharynx and larynx: a treatment planning comparison with fixed field IMRT. Radiother Oncol 2009,92(1):111-117. 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.12.008

van Herk M: Errors and margins in radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol 2004, 14: 52-64. 10.1053/j.semradonc.2003.10.003

van Herk M, Remeijer P, Rasch C, Lebesque JV: The probability of correct target dosage: Dose-population histograms for deriving treatment margins in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000, 47: 1121-1135. 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00518-6

Hurkmans CW, Remeijer P, Lebesque JV, Mijnheer BJ: Set-up verification using portal imaging; review of current clinical practice. Radiother Oncol 2001, 58: 105-120. 10.1016/S0167-8140(00)00260-7

Ove R, Cavalieri R, Noble D, Russo SM: Variation of neck position with image-guided radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2012,35(1):1-5. 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181fe46bb

Hong TS, Tomé WA, Chappell RJ, Chinnaiyan P, Mehta MP, Harari PM: The impact of daily setup variations on head-and-neck intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005, 61: 779-788. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.696

Dionisi F, Palazzi MF, Bracco F, Brambilla MG, Carbonini C, Asnaghi DD, Monti AF, Torresin A: Set-up errors and planning target volume margins in head and neck cancer radiotherapy: a clinical study of image guidance with on-line cone-beam computed tomography. Int J Clin Oncol 2012. [Epub ahead of print]

Sykes JR, Brettle DS, Magee DR, Thwaites DI: Investigation of uncertainties in image registration of cone beam CT to CT on an image-guided radiotherapy system. Phys Med Biol 2009,54(24):7263-7283. 10.1088/0031-9155/54/24/002

Brock KK: Image registration in intensity modulated, image-guided and stereotactic body radiation therapy. Front Radiat Ther Oncol 2007, 40: 94-115.

Dogan N, Song S, Saleh H, Wu J, Murphy MJ: Comparisons of multiple automated anatomy-based image-guidance methods for patient setup before head/neck external beam radiotherapy. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2010,12(1):3337.

Li H, Zhu XR, Zhang L, Dong L, Tung S, Ahamad A, Chao KS, Morrison WH, Rosenthal DI, Schwartz DL, Mohan R, Garden AS: Comparison of 2d radiographic images and 3d cone beam computed tomography for positioning head-and-neck radiotherapy patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008,71(3):916-925. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.008

Kim GY, Pawlicki T, Le QT, Luxton G: Linac-based on-board imaging feasibility and the dosimetric consequences of head roll in head-and-neck IMRT plans. Med Dosim 2008,33(1):93-99. 10.1016/j.meddos.2007.05.004

Ahn PH, Ahn AI, Lee CJ, Shen J, Miller E, Lukaj A, Milan E, Yaparpalvi R, Kalnicki S, Garg MK: Random positional variation among the skull, mandible, and cervical spine with treatment progression during head and neck radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009,73(2):626-633. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.10.007

van Kranen S, van Beek S, Rasch C, van Herk M, Sonke JJ: Setup uncertainties of anatomical sub-regions in head-and-neck cancer patients after offline CBCT guidance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 73: 1566-1573. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.11.035

van Beek S, van Kranen S, Mencarelli A, Remeijer P, Rasch C, van Herk M, Sonke JJ: First clinical experience with a multiple region of interest registration and correction method in radiotherapy of head-and-neck cancer patients. Radiother Oncol 2010,94(2):213-217. 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.017

van Kranen S, van Beek S, Mencarelli A, Rasch C, van Herk M, Sonke JJ: Correction strategies to manage deformations in head-and-neck radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2010,94(2):199-205. 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.12.016

Den RB, Doemer A, Kubicek G, Bednarz G, Galvin JM, Keane WM, Xiao Y, Machtay M: Daily Image Guidance With Cone-Beam Computed Tomography for Head-and-Neck Cancer Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy: A Prospective Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010, 76: 1353-1359. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.03.059

Murphy M: Image-guided patient positioning: if one cannot correct for rotational offsets in external-beam radiotherapy setup, how should rotational offsets be managed? Med Phys 2007,34(6):1880-1883. 10.1118/1.2731485

Willoughby TR, Kupelian PA, Pouliot J, Shinohara K, Aubin M, Roach M 3rd, Skrumeda LL, Balter JM, Litzenberg DW, Hadley SW, Wei JT, Sandler HM: Target localization and real-time tracking using the Calypso 4D Localization Systemin patients with localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006, 65: 528-534. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.050

Wang C, Chong F, Wu J, Lai M, Cheng J: Body weight loss associates with set-up error in nasopharyngeal cancer patients undergoing image guided radiotherapy [abstract]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007, 69: s203.

van Asselen B, Dehnad H, Raaijmakers CP, Roesink JM, Lagendijk JJ, Terhaard CH: The dose to the parotid glands with IMRT for oropharyngeal tumor: the effect of reduction of positioning margins. Radiother Oncol 2002, 64: 197-204. 10.1016/S0167-8140(02)00152-4

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Science Foundation of Key Hospital Clinical Program of Ministry of Health, P.R. China (No. 2010-178), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81071836), the Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2010) and the Cultivating Foundation of Education-Bureau of Guangdong Province(No. LYM09007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors indicate no actual or potential conflicts of interest exist.

Authors’ contributions

The authors contributions are the following: W-JY and YS contributed to literature research, study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of findings and writing of the manuscript. FC and J-LF contributed to image registration and data collection. RG and X-LY contributed to patient recruitment, data collection and data analysis. Z-YQ and M-ZL contributed to study design and carried out the quality assurance. YG (PhD, professor) contributed to data analyses. JM contributed to data collection, study design, critical review of data analyses, interpretation of findings and critical edit of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Wen-Jing Yin, Ying Sun contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yin, WJ., Sun, Y., Chi, F. et al. Evaluation of inter-fraction and intra-fraction errors during volumetric modulated arc therapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Radiat Oncol 8, 78 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-8-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-8-78