Abstract

Background

The dose distribution to the rectum, delineated as solid organ, rectal wall and rectal surface, in 3D conformal (3D-CRT) and intensity-modulated radiotherapy treatment (IMRT) planning for localized prostate cancer was evaluated.

Materials and methods

In a retrospective planning study 3-field, 4-field and IMRT treatment plans were analyzed for ten patients with localized prostate cancer. The dose to the rectum was evaluated based on dose-volume histograms of 1) the entire rectal volume (DVH) 2) manually delineated rectal wall (DWH) 3) rectal wall with 3 mm wall thickness (DWH3) 4) and the rectal surface (DSH). The influence of the rectal filling and of the seminal vesicles' anatomy on these dose parameters was investigated. A literature review of the dose-volume relationship for late rectal toxicity was conducted.

Results

In 3D-CRT (3-field and 4-field) the dose parameters differed most in the mid-dose region: the DWH showed significantly lower doses to the rectum (8.7% ± 4.2%) compared to the DWH3 and the DSH. In IMRT the differences between dose parameters were larger in comparison with 3D-CRT. Differences were statistically significant between DVH and all other dose parameters and between DWH and DSH. Mean doses were increased by 23.6% ± 8.7% in the DSH compared to the DVH in the mid-dose region. Furthermore, both the rectal filling and the anatomy of the seminal vesicles influenced the relationship between the dose parameters: a significant correlation of the difference between DVH and DWH and the rectal volume was seen in IMRT treatment.

Discussion

The method of delineating the rectum significantly influenced the dose representation in the dose-volume histogram. This effect was pronounced in IMRT treatment planning compared to 3D-CRT. For integration of dose-volume parameters from the literature into clinical practice these results have to be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Dose escalation has been effective in radiotherapy treatment of localized prostate cancer. Especially intermediate risk patients benefit from doses higher than 70Gy, whether low and high risk patients do so is controversial [1].

Late rectal toxicity, in particular late rectal bleeding, turned out to be the limiting factor in dose escalation [2]. The Patterns of Care Study stated that the incidence of severe rectal and bladder complications almost doubled when dose levels were increased beyond 70Gy with conventional treatment [3]. Three dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) in comparison to conventional radiotherapy resulted in lower rates of late rectal toxicity [4] and allowed the safe administration of doses up to 80Gy. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) has been indicated to be beneficial in comparison with 3D-CRT and made further dose escalation to 86.4Gy possible [5].

The improvements from conventional RT to 3D-CRT and from 3D-CRT to IMRT are due to more conformal dose distributions with the high dose region confined to the target volume and sparing of organs-at-risk [6, 7]. The correlation between the volume of the rectum within the high dose region and the risk for late rectal toxicity suggested a dose volume effect [8].

Dose-volume histograms (DVH) are widely used to evaluate treatment plans and to estimate the risk for toxicity. For solid organs like most tumors, liver or parotid gland the DVH is based on the volume encompassed by the outer contour of the organ. For "hollow" organs like the rectum or bladder, the use of the DVH is controversial as this implicates that rectum and bladder are solid organs. From a radiobiological point of view the rectal wall without its filling defines the critical structure. The content of the hollow organ is irrelevant in terms of risk of complication. Therefore dose-wall histogram (DWH) and dose-surface histogram (DSH) have been suggested to describe the dose to hollow organs in a more appropriate way. Whereas DVH and DWH calculate dose distributions to 3D volumes (entire rectal volume and rectal wall respectively) DSH calculates dose distributions to 2D surfaces, e.g. the outer contour of the rectal wall.

This study compared and analyzed the dose distribution of the rectal DVH, DWH and DSH in 3D-CRT and IMRT treatment planning for prostate cancer. A literature review of the association of these dose parameters with late rectal toxicity was conducted.

Materials and methods

This retrospective planning study included ten consecutive patients treated for localized prostate cancer at the Department of Radiation Oncology of the University of Wuerzburg, Germany, between August 2003 and November 2003.

A spiral planning computed tomography (CT) scan was acquired in the supine position. Slice thickness was 5 mm. Patients were advised to have an empty bowel and a full bladder. A full bladder was advised to keep larger parts of the bladder outside the treatment fields. Simultaneously, a distended rectum has been demonstrated to be not reproducible during the total time of treatment [9]. Patients with a distended rectum in the planning CT received a second CT study in the first or second week of treatment. If the rectal filling was significantly smaller, a new treatment plan based on the second planning CT was generated.

Oncentra™ Treatment Planning (OTP) Version 1.3 (Nucletron, Veenendaal, Netherlands), now Masterplan™, was utilized for treatment planning.

The clinical target volume (CTV) encompassed the prostate gland and seminal vesicles to simulate treatment plans with high risk of vesicle involvement. This target volume concept was used because IMRT is particularly beneficial for concave targets wrapped around organs-at-risk (OAR) [10]. The planning target volume 1 (PTV 1) was generated with a 3D margin of 5 mm around the GTV. PTV 1 was not allowed to overlap with the rectum. PTV 2 was generated by defining a 3D margin of 10 mm around the CTV but only 7 mm in posterior direction.

The bladder (as a solid organ) and both femoral heads were defined as OARs. The rectum was contoured in four different ways: 1) rectal wall based on manual delineation of the inner and outer contour of the rectal wall 2) rectal wall based on manual delineation of the outer contour of the rectal wall and automatic calculation the inner contour using a 3 mm margin [11]3) entire rectal volume including the rectal wall and the rectal lumen 4) rectal surface as the outer contour of the rectal wall. For all four approaches the rectum was confined to 1 cm above to 1 cm below PTV 2 in superior-inferior direction. Therefore, the delineated OAR rectum was different from the anatomical anal canal and rectum as the most superior and inferior parts were not included into the OAR. Anal canal and rectum were not delineated as different OARs to make the analysis and presentation of results more straight-forward [12].

Treatment was planned for a Siemens PRIMUS™ linear accelerator with 6 MV and 18 MV photon energy and a multi-leaf collimator with 1 cm leaf width. The isocenter was placed in the geometrical center of PTV 2. Two 3D-CRT treatment plans were generated for each patient with a prescription dose of 70Gy to PTV 2 according to ICRU 50. Three-field plans with gantry angles of 0° (6 MV), 100° (18 MV) and 260° (18 MV) and four-field plans with gantry angles of 0° (6 MV), 90° (18 MV), 180° (18 MV) and 270° (18 MV) were generated.

A third treatment plan with step-and-shoot IMRT was generated for each patient using optimization objectives listed in Table 1. A simultaneous-integrated boost (SIB) [10] concept with a prescription dose of 66Gy to PTV 2 and a prescription dose of 73Gy to PTV 1 in 33 fractions was applied. Seven beams with 6 MV photon energy were used; the isocentre was placed in the centre of the PTV2. Five intensity levels were allowed for the optimization with a minimum segment size of 2 cm2 and a maximum of 10 segments per beam.

After plan generation the dose distribution was calculated for targets and OARs of each treatment plan. For the rectum the dose distribution to the manually delineated rectal wall (DWH), to the semi-automatic delineated rectal wall with 3 mm wall thickness (DWH3) and to the solid rectum including the lumen (DVH) were calculated. The dose distribution to the outer surface of the rectal wall (DSH) was calculated using the CERR software developed at Washington University in St. Louis [13]. Dx (Gy) denotes the minimal dose (Gy) delivered to x volume percent (x area percent for the DSH) of the evaluated volume-of-interest (VOI).

Dose parameters were compared using student's t-test for matched pairs. The Spearman's rank correlation was utilized to test the correlation between pairs of values. For statistical analysis Statistica 6.0 (Statsoft, Tulsa, USA) was utilized. Differences were considered significant for p < 0.05.

Results

The three-field treatment plans compared with the four-field plans resulted in significantly decreased doses to the rectum in the low dose region D70 and D90. The relationship between rectal DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH was not different between the three-field and the four-field plans. Therefore, only results of the 3-field plans are reported in the following and referred to as 3D-CRT in comparison to results from the IMRT treatment plans.

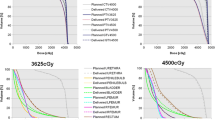

The relationship between DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH in 3D-CRT treatment planning is shown in Figure 1a. In the high-dose region D5 to D20 an almost identical dose distribution to the rectum was shown by all four approaches. In the mid-dose region D30 to D50 the doses displayed in the DWH were significantly lower compared to doses in the DSH and the DWH3: mean difference of 8.7% ± 4.2% (mean ± SD). In the low-dose region of D70 and D90 the DVH showed significantly higher dose of 6.8% ± 2.2%.

Correlation between corresponding dose parameters was investigated by the nonparametric Spearman's rank test. A highly significant linear correlation between pairs of DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH parameters was shown. Best correlation was seen between DSH and DWH3 (R2 = 0.996), worst correlation between DVH and DWH (R2 = 0.939). The slope of linear fit lines ranged between 0.997 (DSH and DWH3) and 1.03 (DVH vs. DWH3).

Comparing 3D-CRT with IMRT treatment plans, more pronounced differences between dose parameters were seen for the latter (Fig 1b). In IMRT the differences were statistically significant between DVH and all other dose parameters, between DWH and DSH but not between DWH and DWH3 and between DSH and DWH3. In the high-, mid- and low-dose region the DSH showed significantly higher doses to the rectum compared to the DVH. Doses in the DSH were increased by 23.6% ± 8.7% compared to the DVH in the mid-dose region; differences were smaller in the high-dose region (9.2% ± 6.6%) and in the low-dose region (6.2% ± 3.9%). The DWH showed decreased doses compared with the DWH3 in all dose regions.

In Fig. 2 the corresponding results of DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH were plotted and linear fit lines were calculated. In general correlation between dose parameters was worse in IMRT plans compared to 3D-CRT plans. Best correlation was seen between DSH and DWH3 (R2 = 0.994) and worst correlation between DSH and DVH (R2 = 0.930); the slope of linear fit lines ranged between 1.01 (DWH vs. DWH3) and 1.11 (DVH vs. DSH).

The influence of the rectal volume, the degree of rectal filling, on the relationship between the dose parameters was investigated. Patients were equally divided into two sub-groups according to the rectal volume.

In 3D-CRT treatment planning, no significant difference was seen between DWH3, DVH and DSH for patients with small rectal volumes (n = 5). For patients with a distended rectum (n = 5) DSH and DWH showed identical results but DVH showed significantly lower dose to the rectum in the mid-dose region by 6.3% ± 7.2%. In the IMRT treatment plans the influence of the rectal volume on the relationship between dose parameters was different. The order of the dose distribution to the rectum was not different between the sub-groups: DSH > DWH3 > DWH > DVH. However, differences between dose parameters were larger in the sub-group with a distended rectum. In the mid-dose region the difference between DVH and DWH was 7.5% ± 3.9% and 19.1% ± 4.9% in the subgroup with small rectal volumes and with a distended rectum, respectively. A statistical significant correlation (r = 0.81) between the rectal volume and the difference between DVH and DWH was observed (Fig 3).

Furthermore, the influence of the anatomy of the seminal vesicles on the relationship between the dose parameters was tested. Two sub-groups were generated with five patients each. The criterion was how far the seminal vesicles were wrapped around the rectum.

In the 3D-CRT plans a significant difference between DSH/DWH3 vs. DVH was seen for patients with the seminal vesicles confined to the anterior rectal wall. With the seminal vesicles wrapped around the rectum no difference between DSH, DWH3 and DVH was found. Contrary, in the IMRT treatment plans the anatomy of the seminal vesicles influenced the relationship between the dose parameters only marginally.

Dose distribution to the rectum was compared between IMRT and 3D-CRT treatment. Depending on the way of contouring the rectum the benefit of IMRT in sparing the rectum was different (Fig. 4). Comparing IMRT and 3D-CRT the IMRT technique resulted in 23% ± 15% decreased doses to the rectal DVH in the mid dose region. Based on DWH3 the benefit of the IMRT technique was 11% ± 11% and based on DSH the benefit was reduced to 7% ± 10%.

Discussion

Reducing rectal toxicity represents a major challenge in radiotherapy treatment planning for prostate cancer. Treatment with escalated doses was shown to result in improved rates of local control [14, 15] but simultaneously higher doses to the rectum were found to be correlated with increased rates of late rectal toxicity. Reliable tools in treatment planning for estimating the risk of toxicity are therefore essential. The dose-volume histogram is a common tool to express the dose that is delivered to targets and OARs. Though dose-volume histograms do not provide spatial information, i.e. the location of the high- and low-dose regions ("hot" and "cold" spots) inside the volume of interest, multiple studies have shown correlation between dose-volume-histogram parameters and rectal toxicity. In table 2 a literature review about these studies is given.

However, the transfer of the results from table 2 into clinical practice is complicated by the different way of contouring the rectum, different toxicity endpoints and different classifications of rectal toxicity in the literature.

Within this retrospective planning study it was demonstrated that the method of contouring the rectum significantly influenced the "dose to the rectum" represented in the dose-volume histogram. In general, delineation of the rectal volume as a solid organ underestimated the exposure of the rectum compared to delineation of the rectal surface or the rectal wall. The differences were larger in IMRT treatment planning compared to 3D-CRT. For one single patient the dose to the rectum in the mid-dose region was 35% higher in the DSH compared to the DVH. The rectum was delineated from 1 cm superior to 1 cm inferior the PTV. The delineated OAR rectum constituted a fairly constant fraction of the anatomical anus/rectum averaged over all patients (73% ± 4%). Portions of the rectum outside the beam, receiving very low doses, were therefore excluded from analysis. Differences between dose parameters would have been smaller if the complete anatomical anus and rectum would have been contoured.

It was also demonstrated that there was no constant relationship between dose parameters DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH for all patients. Both the rectal volume, the degree of the rectal filling, and the anatomy of the seminal vesicles were shown to be relevant. The pattern how these anatomic characteristics influenced the relationship between DWH3, DWH, DVH and DSH was different in IMRT and 3D-CRT treatment planning. Because of significant differences between dose parameters and because dose volume histograms do not provide spatial information the importance of reviewing the dose distribution in every single CT slice and not only relying on dose parameters has to be stressed.

Others studies compared rectal DVH, DWH and DSH in treatment planning of the prostate [16–20]. Using a cylindrical model for the rectum Fiorino et al. described substantial differences between DVH and DWH for a "full" rectum but only small differences for an "empty" rectum. For patients with a distended rectum the DSH was close to the DWH. Boehmer et al. [20] showed that the length of delineating the rectum in superior-inferior direction significantly influenced the dose to the rectum and therefore should be standardized. However, all these studies are based on 3D-CRT. In this work it has been clearly demonstrated that a one-to-one transfer of the results from 3D-CRT to IMRT treatment planning is not possible.

Another interesting result of this study was the finding that the dose to the manually delineated rectal wall (DWH) was different from the dose to the semi-automatically generated rectal wall with 3 mm wall thickness (DWH3). The choice of the 3-mm wall thickness is supported by the study of Rasmussen, in which the rectal wall thickness measured by ultrasound was found to have a median of 2.6 mm [21]. Tucker et al. reported only small differences of the DWH for rectal wall thicknesses ranging between 2 mm and 5 mm [19]. As the patients in this study were treated in a supine position the intra-rectal feces moved to the posterior rectal wall due to gravity. With CT density values of the rectal wall often very similar to the density of the filling a precise delineation of the inner contour of the rectal wall was difficult for some patients resulting in asymmetric rectal wall thicknesses between anterior (within high-dose region) and posterior (within mid- to low-dose region) rectal wall. It is likely that this explains the differences between DWH3 and DWH and because of this difficulty and uncertainty we do not advocate delineating the inner contour of the rectum manually. Though automatic generation of the DWH3 reduced uncertainties compared to DWH, the thickness of the rectal wall is dependent on the rectal distension and consequently not constant. Meijer et al. described a more sophisticated method of automatic DWH generation [18]: based on the delineated outer rectal contour the inner contour was generated automatically taking the rectal distension into account.

Delineation of the outer contour of the rectum was found to be associated with small intra- and inter-observer variability [22, 23]. Consequently, in analysis of DVH and DSH uncertainties are expected to be lower compared to DWH analysis. Furthermore, generation of the DSH and the DVH are known to be sensitive to parameters such as voxel dimensions and dose calculation grid size [16]. These facts could partially be responsible for differences between dose parameters.

Recently, de Crevoisier et al. showed an increased risk of local failure and simultaneously a lower incidence of late rectal bleeding for patients with a distended rectum on the planning CT study [9]. Treatment planning based on a planning CT with distended rectum introduced a systematic error with the prostate and the anterior rectal wall moving posterior out of the high-dose-region during the treatment. Repetition of the planning CT study in case of a distended rectum was suggested to avoid this error. Additionally, good agreement between DVH and DWH was shown in case of an empty rectum making transfer of constraints form the literature to treatment planning more reliable.

The fact that one single planning CT study is only a snapshot of the patients' anatomy has to be considered for the interpretation of dose-volume histograms. Image-guided treatment techniques are thought to correct differences between treatment planning and the current anatomy at the time of treatment [24–27]. Recently, technologies introduced 3D volume imaging into the treatment room with sufficient soft-tissue contrast for visualization of the prostate and OARs [28]. Such image-guided treatment protocol are expected to allow a substantial reduction of safety margins and consequence in a further escalation of the treatment dose [25].

Comparison of 3D-CRT and IMRT in terms of sparing the rectum was not aim of this study. A simultaneous integrated boost concept was applied for the IMRT plans whereas a homogenous dose distribution without field size reduction was planned for the 3D-CRT plans. It was interesting to note that the "benefit" of IMRT in comparison to 3D-CRT was strongly dependent on the way of contouring the rectum. Doses to the rectum were reduced in the IMRT plan by 23%, 11% and 7% with the calculation based on the rectal DVH, DWH3 and the DSH.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the method of delineating the rectum significantly influenced the dose representation in external beam radiotherapy of localized prostate cancer. Differences between the dose parameters, based on delineation of the rectal wall, rectal volume and rectal surface, were larger in IMRT treatment planning compared with 3D-CRT. It was shown that the patient's anatomy, both the rectal filling and the anatomy of the seminal vesicles, influenced the relationship between the four evaluated parameters. For integration of dose-volume parameters from the literature into treatment planning these results have to be considered: a one-to-one transfer of the results from 3D-CRT to IMRT treatment planning may be associated with substantial errors.

References

Kupelian P, Kuban D, Thames H, Levy L, Horwitz E, Martinez A, Michalski J, Pisansky T, Sandler H, Shipley W, Zelefsky M, Zietman A: Improved biochemical relapse-free survival with increased external radiation doses in patients with localized prostate cancer: The combined experience of nine institutions in patients treated in 1994 and 1995. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005,61(2):415-419. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.018

Schultheiss TE, Lee WR, Hunt MA, Hanlon AL, Peter RS, Hanks GE: Late GI and GU complications in the treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1997,37(1):3-11. 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00468-3

Leibel SA, Hanks GE, Kramer S: Patterns of care outcome studies: results of the national practice in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1984,10(3):401-409.

Dearnaley DP, Khoo VS, Norman AR, Meyer L, Nahum A, Tait D, Yarnold J, Horwich A: Comparison of radiation side-effects of conformal and conventional radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999,353(9149):267-272. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05180-0

Zelefsky MJ, Fuks Z, Hunt M, Yamada Y, Marion C, Ling CC, Amols H, Venkatraman ES, Leibel SA: High-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer: early toxicity and biochemical outcome in 772 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002,53(5):1111-1116. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02857-2

Oh CE, Antes K, Darby M, Song S, Starkschall G: Comparison of 2D conventional, 3D conformal, and intensity-modulated treatment planning techniques for patients with prostate cancer with regard to target-dose homogeneity and dose to critical, uninvolved structures. Med Dosim 1999,24(4):255-263. 10.1016/S0958-3947(99)00030-8

Zelefsky MJ, Fuks Z, Happersett L, Lee HJ, Ling CC, Burman CM, Hunt M, Wolfe T, Venkatraman ES, Jackson A, Skwarchuk M, Leibel SA: Clinical experience with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol 2000,55(3):241-249. 10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00100-0

Lee WR, Hanks GE, Hanlon AL, Schultheiss TE, Hunt MA: Lateral rectal shielding reduces late rectal morbidity following high dose three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer: further evidence for a significant dose effect. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996,35(2):251-257. 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00064-8

de Crevoisier R, Tucker SL, Dong L, Mohan R, Cheung R, Cox JD, Kuban DA: Increased risk of biochemical and local failure in patients with distended rectum on the planning CT for prostate cancer radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005,62(4):965-973. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.032

Bos LJ, Damen EM, de Boer RW, Mijnheer BJ, McShan DL, Fraass BA, Kessler ML, Lebesque JV: Reduction of rectal dose by integration of the boost in the large-field treatment plan for prostate irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002,52(1):254-265. 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)02676-1

Vargas C, Yan D, Kestin LL, Krauss D, Lockman DM, Brabbins DS, Martinez AA: Phase II dose escalation study of image-guided adaptive radiotherapy for prostate cancer: use of dose-volume constraints to achieve rectal isotoxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005,63(1):141-149. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.017

Guckenberger M, Pohl F, Baier K, Meyer J, Vordermark D, Flentje M: Adverse effect of a distended rectum in intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) treatment planning of prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol 2006.

Deasy JO, Blanco AI, Clark VH: CERR: a computational environment for radiotherapy research. Med Phys 2003,30(5):979-985. 10.1118/1.1568978

Pollack A, Zagars GK, Starkschall G, Antolak JA, Lee JJ, Huang E, von Eschenbach AC, Kuban DA, Rosen I: Prostate cancer radiation dose response: results of the M. D. Anderson phase III randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002,53(5):1097-1105. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02829-8

Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, Rossi CJJ, Miller DW, Adams JA, Shipley WU: Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. Jama 2005,294(10):1233-1239. 10.1001/jama.294.10.1233

Fiorino C, Gianolini S, Nahum AE: A cylindrical model of the rectum: comparing dose-volume, dose-surface and dose-wall histograms in the radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol 2003,48(16):2603-2616. 10.1088/0031-9155/48/16/303

Li S, Boyer A, Lu Y, Chen GT: Analysis of the dose-surface histogram and dose-wall histogram for the rectum and bladder. Med Phys 1997,24(7):1107-1116. 10.1118/1.598014

Meijer GJ, van den Brink M, Hoogeman MS, Meinders J, Lebesque JV: Dose-wall histograms and normalized dose-surface histograms for the rectum: a new method to analyze the dose distribution over the rectum in conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999,45(4):1073-1080. 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00270-9

Tucker SL, Dong L, Cheung R, Johnson J, Mohan R, Huang EH, Liu HH, Thames HD, Kuban D: Comparison of rectal dose-wall histogram versus dose-volume histogram for modeling the incidence of late rectal bleeding after radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004,60(5):1589-1601. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.712

Boehmer D, Kuczer D, Badakhshi H, Stiefel S, Kuschke W, Wernecke KD, Budach V: Influence of organ at risk definition on rectal dose-volume histograms in patients with prostate cancer undergoing external-beam radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol 2006,182(5):277-282. 10.1007/s00066-006-1462-7

Rasmussen SN, Riis P: Rectal wall thickness measured by ultrasound in chronic inflammatory diseases of the colon. Scand J Gastroenterol 1985,20(1):109-114.

Fiorino C, Vavassori V, Sanguineti G, Bianchi C, Cattaneo GM, Piazzolla A, Cozzarini C: Rectum contouring variability in patients treated for prostate cancer: impact on rectum dose-volume histograms and normal tissue complication probability. Radiother Oncol 2002,63(3):249-255. 10.1016/S0167-8140(01)00469-8

Foppiano F, Fiorino C, Frezza G, Greco C, Valdagni R: The impact of contouring uncertainty on rectal 3D dose-volume data: results of a dummy run in a multicenter trial (AIROPROS01-02). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003,57(2):573-579. 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00659-X

Litzenberg DW, Balter JM, Hadley SW, Sandler HM, Willoughby TR, Kupelian PA, Levine L: Influence of intrafraction motion on margins for prostate radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006,65(2):548-553. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.033

Wu Q, Ivaldi G, Liang J, Lockman D, Yan D, Martinez A: Geometric and dosimetric evaluations of an online image-guidance strategy for 3D-CRT of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006,64(5):1596-1609. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.12.029

Bos LJ, van der Geer J, van Herk M, Mijnheer BJ, Lebesque JV, Damen EM: The sensitivity of dose distributions for organ motion and set-up uncertainties in prostate IMRT. Radiother Oncol 2005,76(1):18-26. 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.010

Guckenberger M, Meyer J, Vordermark D, Baier K, Wilbert J, Flentje M: Magnitude and clinical relevance of translational and rotational patient setup errors: A cone-beam CT study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006,65(3):934-942. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.02.019

Smitsmans MH, de Bois J, Sonke JJ, Betgen A, Zijp LJ, Jaffray DA, Lebesque JV, van Herk M: Automatic prostate localization on cone-beam CT scans for high precision image-guided radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005,63(4):975-984. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.973

Hartford AC, Niemierko A, Adams JA, Urie MM, Shipley WU: Conformal irradiation of the prostate: estimating long-term rectal bleeding risk using dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996,36(3):721-730. 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00366-5

Boersma LJ, van den Brink M, Bruce AM, Shouman T, Gras L, te Velde A, Lebesque JV: Estimation of the incidence of late bladder and rectum complications after high-dose (70-78 GY) conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer, using dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998,41(1):83-92. 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00037-6

Storey MR, Pollack A, Zagars G, Smith L, Antolak J, Rosen I: Complications from radiotherapy dose escalation in prostate cancer: preliminary results of a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000,48(3):635-642. 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00700-8

Jackson A, Skwarchuk MW, Zelefsky MJ, Cowen DM, Venkatraman ES, Levegrun S, Burman CM, Kutcher GJ, Fuks Z, Liebel SA, Ling CC: Late rectal bleeding after conformal radiotherapy of prostate cancer. II. Volume effects and dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001,49(3):685-698. 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)01414-0

Fenwick JD, Khoo VS, Nahum AE, Sanchez-Nieto B, Dearnaley DP: Correlations between dose-surface histograms and the incidence of long-term rectal bleeding following conformal or conventional radiotherapy treatment of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001,49(2):473-480. 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)01496-6

Wachter S, Gerstner N, Goldner G, Potzi R, Wambersie A, Potter R: Rectal sequelae after conformal radiotherapy of prostate cancer: dose-volume histograms as predictive factors. Radiother Oncol 2001,59(1):65-70. 10.1016/S0167-8140(01)00281-X

Kupelian PA, Reddy CA, Carlson TP, Willoughby TR: Dose/volume relationship of late rectal bleeding after external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: absolute or relative rectal volume? Cancer J 2002,8(1):62-66.

Huang EH, Pollack A, Levy L, Starkschall G, Dong L, Rosen I, Kuban DA: Late rectal toxicity: dose-volume effects of conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2002,54(5):1314-1321. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)03742-2

Fiorino C, Sanguineti G, Cozzarini C, Fellin G, Foppiano F, Menegotti L, Piazzolla A, Vavassori V, Valdagni R: Rectal dose-volume constraints in high-dose radiotherapy of localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003,57(4):953-962. 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00665-5

Greco C, Mazzetta C, Cattani F, Tosi G, Castiglioni S, Fodor A, Orecchia R: Finding dose-volume constraints to reduce late rectal toxicity following 3D-conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) of prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol 2003,69(2):215-222. 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.08.003

Akimoto T, Muramatsu H, Takahashi M, Saito J, Kitamoto Y, Harashima K, Miyazawa Y, Yamada M, Ito K, Kurokawa K, Yamanaka H, Nakano T, Mitsuhashi N, Niibe H: Rectal bleeding after hypofractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: correlation between clinical and dosimetric parameters and the incidence of grade 2 or worse rectal bleeding. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004,60(4):1033-1039. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.07.695

Koper PC, Heemsbergen WD, Hoogeman MS, Jansen PP, Hart GA, Wijnmaalen AJ, van Os M, Boersma LJ, Lebesque JV, Levendag P: Impact of volume and location of irradiated rectum wall on rectal blood loss after radiotherapy of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004,58(4):1072-1082. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.08.008

Lee CM, Lee RJ, Handrahan DL, Sause WT: Comparison of late rectal toxicity from conventional versus three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: analysis of clinical and dosimetric factors. Urology 2005,65(1):114-119. 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.037

Peeters ST, Lebesque JV, Heemsbergen WD, van Putten WL, Slot A, Dielwart MF, Koper PC: Localized volume effects for late rectal and anal toxicity after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006,64(4):1151-1161. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

MG designed the analysis, generated the treatment plans, performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript.

JM was involved in the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript.

KB participated in the study design and revised the manuscript.

DV participated in the study design and revised the manuscript.

MF participated in the study design and revised the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Guckenberger, M., Meyer, J., Baier, K. et al. Distinct effects of rectum delineation methods in 3D-confromal vs. IMRT treatment planning of prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol 1, 34 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-1-34

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-717X-1-34