Abstract

Background

Widespread dissemination and implementation of evidence-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) linkage-to-care (LTC) interventions is essential for improving HIV-positive patients' health outcomes and reducing transmission to uninfected others. To date, however, little work has focused on identifying factors associated with intentions to adopt LTC interventions among policy makers, including city, state, and territory health department AIDS directors who play a critical role in deciding whether an intervention is endorsed, distributed, and/or funded throughout their region.

Methods

Between December 2010 and February 2011, we administered an online questionnaire with state, territory, and city health department AIDS directors throughout the United States to identify factors associated with intentions to adopt an LTC intervention. Guided by pertinent theoretical frameworks, including the Diffusion of Innovations and the "push-pull" capacity model, we assessed participants' attitudes towards the intervention, perceived organizational and contextual demand and support for the intervention, likelihood of adoption given endorsement from stakeholder groups (e.g., academic researchers, federal agencies, activist organizations), and likelihood of enabling future dissemination efforts by recommending the intervention to other health departments and community-based organizations.

Results

Forty-four participants (67% of the eligible sample) completed the online questionnaire. Approximately one-third (34.9%) reported that they intended to adopt the LTC intervention for use in their city, state, or territory in the future. Consistent with prior, related work, these participants were classified as LTC intervention "adopters" and were compared to "nonadopters" for data analysis. Overall, adopters reported more positive attitudes and greater perceived demand and support for the intervention than did nonadopters. Further, participants varied with their intention to adopt the LTC intervention in the future depending on endorsement from different key stakeholder groups. Most participants indicated that they would support the dissemination of the intervention by recommending it to other health departments and community-based organizations.

Conclusions

Findings from this exploratory study provide initial insight into factors associated with public health policy makers' intentions to adopt an LTC intervention. Implications for future research in this area, as well as potential policy-related strategies for enhancing the adoption of LTC interventions, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Timely linkage of newly diagnosed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals to healthcare is critical for improving patient health outcomes and reducing transmission of HIV to uninfected others [1–4]. Unfortunately, approximately 20% to 40% of newly diagnosed HIV-positive patients in the United States fail to be linked to care in a timely fashion [2, 4–6]. Researchers have identified numerous individual-, contextual-, and structural-level factors associated with delayed entry to HIV care [4, 7–20]; importantly, such information has served as the foundation for the development of several linkage-to-care (LTC) interventions [21–27].

Despite the potential to improve patient and public health outcomes [1–4, 28, 29], existing evidence-based HIV LTC interventions have yet to be widely and systematically disseminated and implemented in community-based organizations (CBOs) and health departments throughout the United States. In order to accelerate national-level scale-up, it is important to identify and understand factors associated with intentions to adopt LTC interventions and use this information to develop and test strategies to encourage intervention adoption and effective implementation among key end users, including consumers, organizations, and policy makers.

While limited empirical evidence exists regarding barriers to adoption and effective implementation of LTC interventions (see [30] for a notable exception), related work with evidence-based HIV prevention interventions has identified a range of influential factors, including characteristics of the intervention, organizational culture and climate, program champions, financial resources, and staffing [31–45]. For example, Miller [46] found organizational commitment, resources, and maturity to be distinguishing factors associated with the degree to which an HIV prevention program was adopted in 38 CBOs. Additionally, DiFranceisco and colleagues [31] identified individual- and organizational-level factors associated with attitudes towards using research-based HIV prevention interventions among a sample of 77 AIDS service organizations in the United States.

Comparatively less empirical work, however, has focused on understanding factors associated with intentions to adopt HIV interventions among city, state, and territory policy makers (so-called small p policy makers [47, 48]), including state, city, and territory health department AIDS directors. Indeed, health department AIDS directors play a critical role in the dissemination and implementation of interventions in their state, city, or territory, as they are able to actively promote and endorse the adoption of particular interventions within their coverage area or allocate funds for the implementation of particular interventions. Indeed, little is known about factors that influence policy makers' decision-making process regarding the adoption of evidence-based HIV-focused interventions, including LTC interventions.

Given the paucity of research on factors affecting health department AIDS directors' intentions to adopt evidence-based HIV-focused interventions, combined with their "gatekeeper" status and potential role in accelerating dissemination efforts, the objectives of the present study were two-fold: (1) to characterize health department AIDS directors' overall intentions to adopt an evidence-based LTC intervention for use in their state, city, or territory and (2) to compare responses between participants classified as "adopters" versus "nonadopters" on key theory-based constructs.

The current study focused on the adoption of a specific evidence-based LTC intervention, ARTAS (i.e., Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study) [19, 22, 23]. Briefly, ARTAS is a multisession, strengths-based case management [49, 50] intervention designed to link newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals to HIV medical care. In the ARTAS intervention, newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals meet with a case manager up to five times over a 90-day period. During these sessions, the case manager builds rapport with the client, helps the client identify barriers toward accessing HIV medical care, discusses strategies for overcoming these barriers, and supports the client in seeking HIV medical care. We opted to focus specifically on ARTAS because it is the only LTC intervention to date that has demonstrated positive outcomes in both an efficacy and an effectiveness trial [19, 22, 23], thus providing strong evidence to warrant its widespread use.

Methods

Participants

Eligible participants included the 65 health department AIDS directors from all 50 US states, US territories (n = 8; American Samoa, Guam, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Puerto Rico, and Virgin Islands), the District of Columbia, and six major US cities that receive direct funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; i.e., Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Procedure

Contact information for each of the 65 AIDS directors was obtained from the online directory of the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD; http://www.nastad.org), a nonprofit national association of state and territory health department HIV/AIDS program directors, and supplemented with health department websites, as needed. Individuals were invited to participate in the study via email, which included a link to a 30-minute questionnaire administered through Survey Monkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com, 2011). Data collection occurred from December 2010 to February 2011. The questionnaire included survey items, as well as a brief description of ARTAS (e.g., content, purpose, prior research evidence, and recommended staffing) in order to facilitate informed decision making. If directors felt that they were not the most appropriate person to complete the questionnaire, they were asked to forward the study invitation to an appropriate representative within the health department (e.g., AIDS prevention coordinator/program manager). Participants received email and/or phone reminders each week for up to three weeks after initial contact and were provided the option of receiving a $30 Visa gift card for participation in the study.

Measures

In absence of a standardized questionnaire designed specifically for our target population (e.g., health department AIDS directors) and evidence-based intervention (e.g., LTC intervention), we drew on several theoretical frameworks to inform the selection of key constructs in our questionnaire [47, 51, 52]. Guided by Rogers' Diffusion of Innovations Theory [52], we included measures to assess participants' attitudes towards the intervention, since attributes of the innovation are associated with innovation adoption [53]. The Diffusion of Innovations Theory also informed our selection of measures to assess participants' likelihood of adoption given endorsement from key stakeholder groups, which served as a proxy for assessing communication channels [52] through which an innovation may be received or promulgated, again influencing end-user adoption. Consistent with Orleans' push-pull capacity model [51, 54], we also included constructs to assess health department AIDS directors' perceived demand and support for the LTC intervention, as "pull" factors can hinder or facilitate the adoption of innovations. Validated measures from prior studies [53, 55–58] were adapted for the specific context of the present study and used to assess the above-mentioned constructs. Finally, we solicited expert review of the questionnaire from key representatives and researchers from CDC, NASTAD, and academia in an effort to bolster the reliability and validity of our findings given the dearth of validated measures in evidence-based public health policy research.

Demographic items

Demographic items included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. Participants were asked to identify their current job position (e.g., health department director, health department prevention coordinator, other), years in current position, and years worked for the health department. Categorical or continuous response options were provided, as appropriate. These items were selected based on use in a prior study examining the dissemination of physical activity programs among state health departments in the United States [55].

Intention to adopt ARTAS

Directors' intentions to adopt ARTAS for use in their city, state, or territory was assessed by a single item, "I will adopt ARTAS for use in my city, state, or territory," and measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Attitudes towards ARTAS

Directors' attitudes towards ARTAS were assessed on a 17-item scale. Consistent with the Diffusion of Innovations Theory [52], we assessed participants' attitudes towards attributes of ARTAS, including its relative advantage (i.e., degree to which an innovation is perceived as better than the idea it supersedes [52]), complexity (i.e., degree to which an innovation is perceived as difficult to understand or use [52]), compatibility (i.e., degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with the existing values, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters [52]), observability (i.e., degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others [52]), and trialability (i.e., degree to which an innovation may be experimented with on a limited basis [52]). We also assessed participants' attitudes towards intervention effectiveness (i.e., performance [59]), cost (i.e., money or other resources [59]), and simplicity (i.e., inverse of complexity [59]) based on our review of the literature [53, 56, 58, 59]. Sample items include, "Even though ARTAS was shown to be effective in research trials, it wouldn't really work in my city, state, or territory," "ARTAS would have a visible and substantial impact on the health status of newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals in my city, state, or territory," and "ARTAS is too complex" (reverse scored) . Items were assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Due to high inter-item correlation, we created a summed scale of attitudes towards ARTAS, with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes towards ARTAS. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.85).

Perceived demand and support for ARTAS

Directors' perceptions of demand and support for ARTAS were assessed on a nine-item scale. Consistent with the push-pull capacity model [51], we included items to assess perceived demand for ARTAS among potential end-user organizations (e.g., CBOs, local health departments), members of the target population (e.g., HIV-positive individuals), and the director's own health department. Sample items include, "There would be a high demand for ARTAS by community-based organizations in my city, state, or territory" and "Linking newly diagnosed HIV-positive individuals to medical care is a high priority in my health department." Items assessed perceived support for ARTAS among political leaders (e.g., governor/mayor and legislature/city council) and health department staff (e.g., administrators and managers). Sample items include, "The governor of my state or territory/mayor of my city would NOT support the use of ARTAS" and "The state and territory legislature/city council would NOT support the use of ARTAS" (reverse scored). All items were assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). We created a summed scale of perceived demand and support for ARTAS, with higher scores indicating greater perceived demand and support. The scale demonstrated relatively poor reliability (α = 0.51).

Likelihood of adoption given endorsement from stakeholders

Fourteen items were used to assess directors' likelihood of adopting ARTAS based on recommendations and endorsement from a variety of key stakeholder groups, as a proxy for assessing communication channels [52]. We selected a range of professional, peer, and nationally based stakeholder organizations involved in HIV care and treatment that would be potential marketing channels for the dissemination of ARTAS in the future. These key stakeholder groups included (1) other states, cities, or territories in the same region; (2) other health department AIDS directors; (3) academic researchers; (4) CBOs; (5) health departments; (6) professional organizations (e.g., HIV Medicine Association); (7) councils/groups (e.g., National Minority AIDS Council); (8) NASTAD; (9) activist organizations (e.g., Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization Project); (10) reputable, online websites (e.g., http://www.thebody.com); (11) US government's National AIDS Strategy; (12) Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); (13) Veterans Administration (VA); and (14) CDC. Each item asked, "If ARTAS was recommended and endorsed by (name of stakeholder group), I would adopt it for use in my state, city, or territory." Responses were assessed individually on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Enabling intervention dissemination

Three items were used to assess whether or not directors intended to enable future dissemination efforts by recommending ARTAS to other key stakeholders, including (1) other health department AIDS directors; (2) CBOs within their city, state, or territory; and (3) local health departments within their state or territory (as applicable). Each item stated, "I would recommend ARTAS to (name of key stakeholder group)." Each item was assessed individually by stakeholder group on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Data analysis

Consistent with the first objective of our exploratory study, descriptive statistics were used to characterize the overall sample in terms of demographics. Descriptive statistics were also used to characterize responses to individual items assessing directors' attitudes towards ARTAS, perceived demand and support for ARTAS, likelihood of adopting ARTAS given endorsement and recommendation from others, and likelihood of enabling intervention dissemination. Inter-item correlations and scale reliability were examined within measures; average scores were computed for scales, where appropriate. Consistent with the second objective of our exploratory study, we compared responses between adopters versus nonadopters on key constructs. Following the approach used in prior research [55], participants were classified as adopters if they responded agree or strongly agree to the single item assessing adoption intentions; those who indicated any other response option (i.e., neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree) were classified as nonadopters. One-way independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine differences between adopters and nonadopters on demographic variables and average scores (where applicable). All analyses were conducted in SPSS v. 17 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

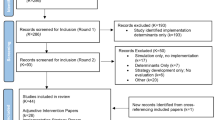

Participant characteristics

Table 1 summarizes demographic characteristics of the overall sample. Of 65 eligible participants, 47 agreed to participate (72%), and 42 provided complete responses to all items (64%). Of the five individuals who provided incomplete responses, two initiated the survey but indicated that they were already implementing an LTC intervention, and thus declined to answer any questions because they did not think it was applicable. Two other participants completed the majority of the questionnaire but failed to answer the last few questions. One individual provided his/her name, but did not answer any of the survey items. Thus, analyses for the present study were restricted to 44 individuals who provided responses to the majority of the questionnaire, representing approximately 67% of the total eligible sample.

Most participants were white (n = 31, 70.5%), female (n = 24, 54.5%), and between 46 and 55 years old (n = 18, 40.9%). Many participants reported having at least a bachelor's degree (n = 20); several also reported having a Master's degree (n = 26). The majority of participants self-identified as the health department AIDS director (n = 29, 67.4%), while a few participants identified as the department AIDS prevention coordinator/program manager (n = 9, 20.9%) or other (e.g., director of policy, director of evaluation, or LTC coordinator; n = 5, 11.7%). Most participants had been in their current position for less than five years (n = 26, 59.1%).

Intentions to adopt ARTAS

Among the 43 participants who provided a response to the item that assessed intentions to adopt ARTAS, 15 (34.9%) responded agree or strongly agree and were subsequently classified as adopters. Consistent with prior work [55], the remaining 28 participants (65.1%) who responded strongly disagree, disagree, or neither agree nor disagree were classified as nonadopters for between-group analyses.

Attitudes towards ARTAS

Descriptive statistics and differences between adopters and nonadopters on each individual item assessing attitudes towards ARTAS can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix A. On average, participants classified as adopters reported more positive attitudes towards ARTAS (M = 3.62, standard deviation [SD] = 0.40) than those classified as nonadopters (M = 3.21, SD = 0.32), t(41) = 3.65, p = .001.

Perceived demand and support for ARTAS

Descriptive statistics and differences between adopters and nonadopters on each individual item assessing perceived demand and support for ARTAS can be found in Additional file 1: Appendix B. On average, participants classified as adopters reported greater perceived demand and support for ARTAS (M = 3.91, SD = 0.40) than those classified as nonadopters (M = 3.66, SD = 0.29), t(41) = 2.38, p = .02. These findings should be interpreted with caution, however, given poor scale reliability (α = .51).

Likelihood of adoption given endorsement from stakeholders

Overall, as displayed in Table 2 a greater percentage of participants reported intentions to adopt ARTAS in the future if ARTAS was recommended and endorsed by CDC (59.1%), the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy (59.1%), HRSA (56.8%), NASTAD (54.5%), or a state, city, or territory health department AIDS director whom the participant respected and trusted (50%). Conversely, a lower percentage of participants reported intentions to adopt ARTAS in the future if ARTAS was recommended and endorsed by reputable online websites (18.2%), VA (25%), or activist organizations (25.6%).

Enabling intervention dissemination

Most participants reported that they would recommend ARTAS to other health departments (56.8%); CBOs in their city, state, or territory (54.5%); and local health departments in their state or territory (61%), respectively.

Discussion

In the current sample of city, state, and territory health department AIDS directors in the United States, 34.9% reported that they would adopt ARTAS for use in their city, state, or territory. Consistent with prior research [55, 60] and several theoretical frameworks [51, 52], participants classified as adopters indicated more positive attitudes towards the LTC intervention and greater perceived demand for ARTAS than those classified as non-adopters. Intentions to adopt ARTAS varied by the type of stakeholder group recommending and endorsing the intervention; greater likelihood of adoption was observed when the LTC intervention was hypothetically endorsed by the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and CDC than if endorsed by reputable online websites and VA. Finally, most participants reported that they would recommend ARTAS to other health departments, CBOs, and local health departments (where applicable).

Findings from this exploratory questionnaire study provide an initial description and identification of theory-based constructs associated with intentions to adopt an evidence-based LTC intervention among city, state, and territory health department AIDS directors throughout the United States. Importantly, future research may focus on developing strategies to increase positive attitudes toward the intervention, create demand and support for the intervention, and leverage particular stakeholder groups as effective intervention marketing channels in order to encourage and accelerate the adoption of LTC interventions among city, state, and territory health department AIDS directors.

While the current study provides an initial step towards better understanding policy makers' decision-making processes regarding the adoption of LTC interventions, additional work is needed to develop this area of inquiry further. Indeed, although evidence-based public health policy research has gained momentum in the past decade, especially in the areas of tobacco, cancer, physical activity, and school health [47, 61, 62], the field would benefit from programmatic efforts to advance both theory and measurement across a variety of public health areas. In the interim, the existing body of work can serve as a starting point for the development of more robust evidence-based public health policy research with specific application towards HIV prevention, treatment, and care interventions.

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. First, responses may be subject to social desirability bias. While procedural safeguards were implemented to reduce such bias (e.g., online questionnaire completed at the discretion of the participant's availability and location), it is possible that participants may have provided less-than-accurate responses because the survey was not anonymous. However, having an independent group (e.g., academic-affiliated investigator) administer the online survey--rather than an entity charged with allocating funds (e.g., CDC, HRSA)--may have reduced the likelihood of biased responses. Second, as is common across most areas of dissemination and implementation research [63], and particularly within evidence-based public health policy research [47, 63], the present study lacked established measures for assessing city, state, and territory policy makers'--specifically health department AIDS directors'--intentions to adopt ARTAS in the future. While constructs in the current study were informed by theoretical frameworks; measures used in related-research studies [47, 51, 52, 60, 62, 64]; and input from expert representatives from CDC, NASTAD, and academia, future work is needed to validate these measures with other HIV-focused interventions and to determine their predictive utility in discriminating between those who actually adopt versus do not adopt interventions in the future.

Identifying ways to promote the adoption of evidence-based LTC interventions among policy makers has the potential to accelerate the transition of such interventions from research to practice settings at the national level, which is essential for realizing the population benefits of our research investments. Although exploratory, the present study contributes to the evidence base in this area and seeks to instigate additional inquiry into this field in a concerted effort to spread evidence-based LTC interventions more quickly and effectively throughout the United States.

Endnote

aFor some analyses, N = 43 because of incomplete data or refusal to answer a question.

References

Mayer KH: Introduction: Linkage, engagement, and retention in HIV care: essential for optimal individual- and community-level outcomes in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl 2): S205-207.

Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, Lewis R, Savetsky J, Sullivan L, Levenson SM, Hingson R: Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998, 158: 734-740. 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734.

Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin HY, Routman JS, Abroms S, Allison J, Chatham A, Raper JL, Saag MS, Mugavero MJ: The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009, 23: 41-49. 10.1089/apc.2008.0132.

Marks G, Gardner LI, Craw J, Crepaz N: Entry and retention in medical care among HIV-diagnosed persons: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010, 24: 2665-2678. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b.

Horberg MA, Aberg JA, Cheever LW, Renner P: O'Brien Kaleba E, Asch SM: Development of national and multiagency HIV care quality measures. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 51: 732-738. 10.1086/655893.

Cunningham WE, Markson LE, Andersen RM, Crystal SH, Fleishman JA, Golin C, Gifford A, Liu HH, Nakazono TT, Morton S: Prevalence and predictors of highly active antiretroviral therapy use in patients with HIV infection in the united states. HCSUS Consortium. HIV Cost and Services Utilization. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000, 25: 115-123. 10.1097/00126334-200010010-00005.

Keller S, Jones J, Erbelding E: Choice of Rapid HIV Testing and Entrance Into Care in Baltimore City Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinics. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011, 25: 237-243. 10.1089/apc.2010.0298.

Bamford LP, Ehrenkranz PD, Eberhart MG, Shpaner M, Brady KA: Factors associated with delayed entry into primary HIV medical care after HIV diagnosis. AIDS. 2010, 24: 928-930. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b116.

Aziz M, Smith KY: Challenges and successes in linking HIV-infected women to care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl 2): S231-237.

Christopoulos KA, Das M, Colfax GN: Linkage and retention in HIV care among men who have sex with men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl 2): S214-222.

Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH: Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. South Med J. 2006, 99: 472-481. 10.1097/01.smj.0000215639.59563.83.

Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Vermund SH: Delayed access to HIV diagnosis and care: Special concerns for the Southern United States. AIDS Care. 2006, 18 (Suppl 1): S35-44.

McCoy SI, Miller WC, MacDonald PD, Hurt CB, Leone PA, Eron JJ, Strauss RP: Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing and linkage to primary care: narratives of people with advanced HIV in the Southeast. AIDS Care. 2009, 21: 1313-1320. 10.1080/09540120902803174.

Reed JB, Hanson D, McNaghten AD, Bertolli J, Teshale E, Gardner L, Sullivan P: HIV testing factors associated with delayed entry into HIV medical care among HIV-infected persons from eighteen states, United States, 2000-2004. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009, 23: 765-773. 10.1089/apc.2008.0213.

Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Nunn A, Beckwith CG: Linkage to care for HIV-infected heterosexual men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl 2): S223-230.

Zaller ND, Holmes L, Dyl AC, Mitty JA, Beckwith CG, Flanigan TP, Rich JD: Linkage to treatment and supportive services among HIV-positive ex-offenders in Project Bridge. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008, 19: 522-531. 10.1353/hpu.0.0030.

Bhatia R, Hartman C, Kallen MA, Graham J, Giordano TP: Persons newly diagnosed with HIV infection are at high risk for depression and poor linkage to care: Results from the steps study. AIDS Behav. 2010

Fuqua V, Chen YH, Packer T, Dowling T, Ick TO, Nguyen B, Colfax GN, Raymond HF: Using Social Networks to Reach Black MSM for HIV Testing and Linkage to Care. AIDS Behav. 2011

Gardner LI, Marks G, Craw J, Metsch L, Strathdee S, Anderson-Mahoney P, del Rio C: Demographic, psychological, and behavioral modifiers of the Antiretroviral Treatment Access Study (ARTAS) intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009, 23: 735-742. 10.1089/apc.2008.0262.

Torian LV, Wiewel EW, Liu KL, Sackoff JE, Frieden TR: Risk factors for delayed initiation of medical care after diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 1181-1187. 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1181.

Leider J, Fettig J, Calderon Y: Engaging HIV-positive individuals in specialized care from an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011, 25: 89-93. 10.1089/apc.2010.0205.

Gardner LI, Metsch LR, Anderson-Mahoney P, Loughlin AM, del Rio C, Strathdee S, Sansom SL, Siegal HA, Greenberg AE, Holmberg SD: Efficacy of a brief case management intervention to link recently diagnosed HIV-infected persons to care. AIDS. 2005, 19: 423-431. 10.1097/01.aids.0000161772.51900.eb.

Craw JA, Gardner LI, Marks G, Rapp RC, Bosshart J, Duffus WA, Rossman A, Coughlin SL, Gruber D, Safford LA: Brief strengths-based case management promotes entry into HIV medical care: results of the antiretroviral treatment access study-II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 47: 597-606. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181684c51.

Mugavero MJ: Improving engagement in HIV care: what can we do?. Top HIV Med. 2008, 16: 156-161.

Wanyenze RK, Hahn JA, Liechty CA, Ragland K, Ronald A, Mayanja-Kizza H, Coates T, Kamya MR, Bangsberg DR: Linkage to HIV Care and Survival Following Inpatient HIV Counseling and Testing. AIDS Behav. 2010

Molitor F, Kuenneth C, Waltermeyer J, Mendoza M, Aguirre A, Brockmann K, Crump C: Linking HIV-infected persons of color and injection drug users to HIV medical and other services: the California Bridge Project. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005, 19: 406-412. 10.1089/apc.2005.19.406.

Molitor F, Waltermeyer J, Mendoza M, Kuenneth C, Aguirre A, Brockmann K, Crump C: Locating and linking to medical care HIV-positive persons without a history of care: findings from the California Bridge Project. AIDS Care. 2006, 18: 456-459. 10.1080/09540120500217397.

Moore RD: Epidemiology of HIV infection in the united states: implications for linkage to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (Suppl 2): S208-213.

Tripathi A, Youmans E, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA: The impact of retention in early HIV Medical Care on viro-immunological parameters and survival: A statewide study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011

Craw J, Gardner L, Rossman A, Gruber D, Noreen O, Jordan D, Rapp R, Simpson C, Phillips K: Structural factors and best practices in implementing a linkage to HIV care program using the ARTAS model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010, 10: 246-10.1186/1472-6963-10-246.

DiFranceisco W, Kelly JA, Otto-Salaj L, McAuliffe TL, Somlai AM, Hackl K, Heckman TG, Holtgrave DR, Rompa DJ: Factors influencing attitudes within AIDS service organizations toward the use of research-based HIV prevention interventions. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999, 11: 72-86.

Dworkin SL, Pinto RM, Hunter J, Rapkin B, Remien RH: Keeping the spirit of community partnerships alive in the scale up of HIV/AIDS prevention: critical reflections on the roll out of DEBI (Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions). Am J Community Psychol. 2008, 42: 51-59. 10.1007/s10464-008-9183-y.

Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, Hamdallah M: The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006, 18: 5-20. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5.

Harshbarger C, Simmons G, Coelho H, Sloop K, Collins C: An empirical assessment of implementation, adaptation, and tailoring: the evaluation of CDC's National Diffusion of VOICES/VOCES. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006, 18: 184-197. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.184.

McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, Gelaude D, Carey JW: Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006, 18: 59-73. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59.

King W, Nu'Man J, Fuller TR, Brown M, Smith S, Howell AV, Little S, Patrick P, Glover L: The diffusion of a community-level HIV intervention for women: lessons learned and best practices. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008, 17: 1055-1066. 10.1089/jwh.2008.1035.

O'Donnell L, Scattergood P, Adler M, Doval AS, Barker M, Kelly JA, Kegeles SM, Rebchook GM, Adams J, Terry MA, Neumann MS: The role of technical assistance in the replication of effective HIV interventions. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000, 12: 99-111.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ: The ADAPT-ITT model: a novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV Interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 47 (Suppl 1): S40-46.

Stallworth JM, Andia JF, Burgess R, Alvarez ME, Collins C: Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions and Hispanic/Latino populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009, 21: 152-163. 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.152.

Collins CB, Hearn KD, Whittier DN, Freeman A, Stallworth JD, Phields M: Implementing Packaged HIV-Prevention Interventions for HIV-Positive Individuals: Considerations for Clinic-Based and Community-Based Interventions. Public Health Reports. 2010, 125: 55-63.

Kelly JA, Sogolow ED, Neumann MS: Future directions and emerging issues in technology transfer between HIV prevention researchers and community-based service providers. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000, 12: 126-141.

Kelly JA, Spielberg F, McAuliffe TL: Defining, designing, implementing, and evaluating phase 4 HIV prevention effectiveness trials for vulnerable populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 47 (Suppl 1): S28-33.

Kelly JA, Somlai AM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL, Amirkhanian YA, Brown KD, Stevenson LY, Fernandez MI, Sitzler C, Gore-Felton C: Distance communication transfer of HIV prevention interventions to service providers. Science. 2004, 305: 1953-1955. 10.1126/science.1100733.

Kelly JA, Heckman TG, Stevenson LY, Williams PN, Ertl T, Hays RB, Leonard NR, O'Donnell L, Terry MA, Sogolow ED, Neumann MS: Transfer of research-based HIV prevention interventions to community service providers: fidelity and adaptation. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000, 12: 87-98.

Miller RL: Adapting an evidence-based intervention: tales of the Hustler Project. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003, 15: 127-138. 10.1521/aeap.15.1.5.127.23612.

Miller RL, Bedney BJ, Guenther-Grey C: Assessing organizational capacity to deliver HIV prevention services collaboratively: tales from the field. Health Educ Behav. 2003, 30: 582-600. 10.1177/1090198103255327.

Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA: Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009, 99: 1576-1583. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224.

Brownson RC, Seiler R, Eyler AA: Measuring the impact of public health policy. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010, 7: A77-

Saleebey D: The strengths perspective in social work practice. 1997, New York: Longman Publishers, 2

Rapp C, Wintersteen R: The strengths model of case management: results from twelve demonstrations. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1989, 13: 23-32.

Orleans CT: Increasing the demand for and use of effective smoking-cessation treatments - Reaping the full health benefits of tobacco-control science and policy gains - In our lifetime. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 33: S340-S348. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.003.

Rogers EM: Diffusion of Innovations. 2003, New York: Free Press, 5

Dearing JW: Applying Diffusion of Innovation Theory to Intervention Development. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009, 19: 503-518. 10.1177/1049731509335569.

Green LW, Orleans CT, Ottoson JM, Cameron R, Pierce JP, Bettinghaus EP: Inferring strategies for disseminating physical activity policies, programs, and practices from the successes of tobacco control. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31: S66-81. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.023.

Brownson RC, Ballew P, Dieffenderfer B, Haire-Joshu D, Heath GW, Kreuter MW, Myers BA: Evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity: what contributes to dissemination by state health departments. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 33: S66-73. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.011. quiz S74-68

Dearing JW, Kreuter MW: Designing for diffusion: how can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations?. Patient Educ Couns. 2010, 81 (Suppl): S100-110.

Jacobs JA, Dodson EA, Baker EA, Deshpande AD, Brownson RC: Barriers to evidence-based decision making in public health: a national survey of chronic disease practitioners. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125: 736-742.

Moore GC, Benbasat I: Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Inf Syst Res. 1991, 2: 192-222. 10.1287/isre.2.3.192.

Dearing JA: Measurement of innovation attributes. [http://www.research-practice.org/umbraco/measures/Innovation%attributes%20measurement.pdf]

Brownson RC, Dodson EA, Stamatakis KA, Casey CM, Elliott MB, Luke DA, Wintrode CG, Kreuter MW: Communicating evidence-based information on cancer prevention to state-level policy makers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011, 103: 306-316. 10.1093/jnci/djq529.

Brownson RC, Jones E: Bridging the gap: translating research into policy and practice. Prev Med. 2009, 49: 313-315. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.008.

Brownson RC, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride TD: Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 30: 164-172. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M: Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011, 38: 65-76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Stamatakis KA, McBride TD, Brownson RC: Communicating prevention messages to policy makers: the role of stories in promoting physical activity. J Phys Act Health. 2010, 7 (Suppl 1): S99-107.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the city, state, and territory health department AIDS directors who participated in the study. In addition, thanks to Ross Brownson, PhD, Professor, Washington University in St. Louis; Charles B. Collins, PhD, Team Leader, Capacity Building Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and Natalie Cramer, Associate Director of Prevention, National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) for their invaluable input and feedback on the questionnaire. Special thanks to research assistants Emily Tubergen, MPH, and Molly Bailey, BA.

This research was supported in part by the Implementation Research Institute (IRI) at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2; Principal Investigator: Enola Proctor, PhD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Electronic supplementary material

13012_2011_469_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Appendix A. Descriptives and Differences between Non-adopters (n = 28) and Adopters (n = 15) on Attitudes Towards ARTAS. Appendix B. Descriptives and Differences between Non-adopters (n = 28) and Adopters (n = 15) on Perceived Organizational and Contextual Demand and Support. (DOC 61 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Norton, W.E. An exploratory study to examine intentions to adopt an evidence-based HIV linkage-to-care intervention among state health department AIDS directors in the United States. Implementation Sci 7, 27 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-27