Abstract

Background

Addressing deficiencies in the dissemination and transfer of research-based knowledge into routine clinical practice is high on the policy agenda both in the UK and internationally.

However, there is lack of clarity between funding agencies as to what represents dissemination. Moreover, the expectations and guidance provided to researchers vary from one agency to another. Against this background, we performed a systematic scoping to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activity.

Methods

We searched twelve electronic databases (including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), the reference lists of included studies and of individual funding agency websites to identify potential studies for inclusion. To be included, papers had to present an explicit framework or plan either designed for use by researchers or that could be used to guide dissemination activity. Papers which mentioned dissemination (but did not provide any detail) in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework, were excluded. References were screened independently by at least two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussion. For each included paper, the source, the date of publication, a description of the main elements of the framework, and whether there was any implicit/explicit reference to theory were extracted. A narrative synthesis was undertaken.

Results

Thirty-three frameworks met our inclusion criteria, 20 of which were designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities. Twenty-eight included frameworks were underpinned at least in part by one or more of three different theoretical approaches, namely persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory, and social marketing.

Conclusions

There are currently a number of theoretically-informed frameworks available to researchers that can be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity. Given the current emphasis on enhancing the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could consider encouraging researchers to adopt a theoretically-informed approach to their research dissemination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare resources are finite, so it is imperative that the delivery of high-quality healthcare is ensured through the successful implementation of cost-effective health technologies. However, there is growing recognition that the full potential for research evidence to improve practice in healthcare settings, either in relation to clinical practice or to managerial practice and decision making, is not yet realised. Addressing deficiencies in the dissemination and transfer of research-based knowledge to routine clinical practice is high on the policy agenda both in the UK [1–5] and internationally [6].

As interest in the research to practice gap has increased, so too has the terminology used to describe the approaches employed [7, 8]. Diffusion, dissemination, implementation, knowledge transfer, knowledge mobilisation, linkage and exchange, and research into practice are all being used to describe overlapping and interrelated concepts and practices. In this review, we have used the term dissemination, which we view as a key element in the research to practice (knowledge translation) continuum. We define dissemination as a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences and the settings in which research findings are to be received and, where appropriate, communicating and interacting with wider policy and health service audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake in decision-making processes and practice.

Most applied health research funding agencies expect and demand some commitment or effort on the part of grant holders to disseminate the findings of their research. However, there does appear to be a lack of clarity between funding agencies as to what represents dissemination [9]. Moreover, although most consider dissemination to be a shared responsibility between those funding and those conducting the research, the expectations on and guidance provided to researchers vary from one agency to another [9].

We have previously highlighted the need for researchers to consider carefully the costs and benefits of dissemination and have raised concerns about the nature and variation in type of guidance issued by funding bodies to their grant holders and applicants [10]. Against this background, we have performed a systematic scoping review with the following two aims: to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities; and to identify and describe any conceptual/organising frameworks relating to knowledge translation continuum that provide enough detail on the dissemination elements that researchers could use it to guide their dissemination activities.

Methods

The following databases were searched to identify potential studies for inclusion: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations (1950 to June 2010); EMBASE (1980 to June 2010); CINAHL (1981 to June 2010); PsycINFO (1806 to June 2010); EconLit (1969 to June 2010); Social Services Abstracts (1979 to June 2010); Social Policy and Practice (1890 to June 2010); Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Cochrane Library 2010: Issue 1).

The search terms were identified through discussion by the research team, by scanning background literature, and by browsing database thesauri. There were no methodological, language, or date restrictions. Details of the database specific search strategies are presented Additional File 1, Appendix 1.

Citation searches of five articles [11–15] identified prior to the database searches were performed in Science Citation Index (Web of Science), MEDLINE (OvidSP), and Google Scholar (February 2009).

As this review was undertaken as part of a wider project aiming to assess the dissemination activity of UK applied and public health researchers [16], we searched the websites of 10 major UK funders of health services and public health research. These were the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, the Chief Scientist Office, the Department of Health Policy Research Programme, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, the Medical Research Council (MRC), the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme, the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme and the Wellcome Trust. We aimed to identify any dissemination/communication frameworks, guides, or plans that were available to grant applicants or holders.

We also interrogated the websites of four key agencies with an established record in the field of dissemination and knowledge transfer. These were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ( AHRQ), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF), and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD).

As a number of databases and websites were searched, some degree of duplication resulted. In order to manage this issue, the titles and abstracts of records were downloaded and imported into EndNote bibliographic software, and duplicate records removed.

References were screened independently by two reviewers; those studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Where it was not possible to exclude articles based on title and abstract alone, full text versions were obtained and their eligibility was assessed independently by two reviewers. Where disagreements occurred, the opinion of a third reviewer was sought and resolved by discussion and arbitration by a third reviewer.

To be eligible for inclusion, papers needed to either present an explicit framework or plan designed to be used by a researcher to guide their dissemination activity, or an explicit framework or plan that referred to dissemination in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework but that provided enough detail on the dissemination elements that a researcher could then use it. Papers that referred to dissemination in the context of a wider knowledge translation framework, but that did not describe in any detail those process elements relating to dissemination were excluded from the review. A list of excluded papers is included in Additional File 2, Appendix 2.

For each included paper we recorded the publication date, a description of the main elements of the framework, whether there was any reference to other included studies, and whether there was an explicit theoretical basis to the framework. Included papers that did not make an explicit reference to an underlying theory were re-examined to determine whether any implicit use of theory could be identified. This entailed scrutinising the references and assessing whether any elements from theories identified in other papers were represented in the text. Data from each paper meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted by one researcher and independently checked for accuracy by a second.

A narrative synthesis [17] of included frameworks was undertaken to present the implicit and explicit theoretical basis of included frameworks and to explore any relationships between them.

Results

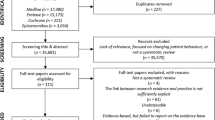

Our searches identified 6,813 potentially relevant references (see Figure 1). Following review of the titles and abstracts, we retrieved 122 full papers for a more detailed screening. From these, we included 33 frameworks (reported in 44 papers) Publications that did not meet our inclusion criteria are listed in Additional File 2, Appendix 2.

Characteristics of conceptual frameworks designed to be used by researchers

Table 1 summarises in chronological order, twenty conceptual frameworks designed for use by researchers [11, 14, 15, 18–34]. Where we have described elements of frameworks that have been reported across multiple publications, these are referenced in the Table.

Theoretical underpinnings of dissemination frameworks

Thirteen of the twenty included dissemination frameworks were either explicitly or implicitly judged to be based on the Persuasive Communication Matrix [35, 36]. Originally derived from a review of the literature of persuasion which sought to operationalise Lasswell's seminal description of persuasive communications as being about 'Who says what in which channel to whom with what effect' [37]. McGuire argued that there are five variables that influence the impact of persuasive communications. These are the source of communication, the message to be communicated, the channels of communication, the characteristics of the audience (receiver), and the setting (destination) in which the communication is received.

Included frameworks were judged to encompass either three [21, 27, 29], four [15, 20, 23, 26, 28, 31, 38], or all five [11, 18, 25] of McGuire's five input variables, namely, the source, channel, message, audience, and setting. The earliest conceptual model included in the review explicitly applied McGuire's five input variables to the dissemination of medical technology assessments [11]. Only one other framework (in its most recent version) explicitly acknowledges McGuire [17]; the original version acknowledged the influence of Winkler et al. on its approach to conceptualising systematic review dissemination [18]. The original version of the CRD approach [18, 39] is itself referred to by two of the other eight frameworks [20, 23]

Diffusion of Innovations theory [40, 41] is explicitly cited by eight of the dissemination frameworks [11, 17, 19, 22, 24, 28, 29, 34]. Diffusion of Innovations offers a theory of how, why, and at what rate practices or innovations spread through defined populations and social systems. The theory proposes that there are intrinsic characteristics of new ideas or innovations that determine their rate of adoption, and that actual uptake occurs over time via a five-phase innovation-decision process (knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation). The included frameworks are focussed on the knowledge and persuasion stages of the innovation-decision process.

Two of the included dissemination frameworks make reference to Social Marketing [42]. One briefly discusses the potential application of social and commercial marketing and advertising principles and strategies in the promotion of non-commercial services, ideas, or research-based knowledge [22]. The other briefly argues that a social marketing approach could take into account a planning process involving 'consumer' oriented research, objective setting, identification of barriers, strategies, and new formats [30]. However, this framework itself does not represent a comprehensive application of social marketing theory and principles, and instead highlights five factors that are focussed around formatting evidence-based information so that it is clear and appealing by defined target audiences.

Three other distinct dissemination frameworks were included, two of which are based on literature reviews and researcher experience [14, 32]. The first framework takes a novel question-based approach and aims to increase researchers' awareness of the type of context information that might prove useful when disseminating knowledge to target audiences [14]. The second framework presents a model that can be used to identify barriers and facilitators and to design interventions to aid the transfer and utilization of research knowledge [32]. The final framework is derived from Two Communities Theory [43] and proposes pragmatic strategies for communicating across conflicting cultures research and policy; it suggests a shift away from simple one-way communication of research to researchers developing collaborative relationships with policy makers [33].

Characteristics of conceptual frameworks relating to knowledge translation that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities

Table 2 summarises in chronological order the dissemination elements of 13 conceptual frameworks relating to knowledge translation that could be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities [13, 44–55].

Theoretical underpinnings of dissemination frameworks

Only two of the included knowledge translation frameworks were judged to encompass four of McGuire's five variables for persuasive communications [45, 47]. One framework [45] explicitly attributes these variables as being derived from Winkler et al[11]. The other [47] refers to strong direct evidence but does not refer to McGuire or any of the other included frameworks.

Diffusion of Innovations theory [40, 41] is explicitly cited in eight of the included knowledge translation frameworks [13, 45–49, 52, 56]. Of these, two represent attempts to operationalise and apply the theory, one in the context of evidence-based decision making and practice [13], and the other to examine how innovations in organisation and delivery of health services spread and are sustained in health service organisations [47, 57]. The other frameworks are exclusively based on the theory and are focussed instead on strategies to accelerate the uptake of evidence-based knowledge and or interventions

Two of the included knowledge translation frameworks [50, 53] are explicitly based on resource or knowledge-based Theory of the Firm [58, 59]. Both frameworks propose that successful knowledge transfer (or competitive advantage) is determined by the type of knowledge to be transferred as well as by the development and deployment of appropriate skills and infrastructure at an organisational level.

Two of the included knowledge translation frameworks purport to be based upon a range of theoretical perspectives. The Coordinated Implementation model is derived from a range of sources, including theories of social influence on attitude change, the Diffusion of Innovations, adult learning, and social marketing [45]. The Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model was developed using concepts from Diffusion of Innovations, social ecology, as well as the health promotion, quality improvement, and implementation literature [52].

Three other distinct knowledge translation frameworks were included, all of which are based on a combination of literature reviews and researcher experience [44, 51, 54].

Conceptual frameworks provided by UK funders

Of the websites of the 10 UK funders of health services and public health research, only the ESRC made a dissemination framework available to grant applicants or holders (see Table 1) [26]. A summary version of another included framework is available via the publications section of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation [60]. However, no reference is made to it in the submission guidance they make available to research applicants.

All of the UK funding bodies made brief references to dissemination in their research grant application guides. These would simply ask applicants to briefly indicate how findings arising from the research will be disseminated (often stating that this should be other than via publication in peer-reviewed journals) so as to promote or facilitate take up by users in the health services.

Discussion

This systematic scoping review presents to our knowledge the most comprehensive overview of conceptual/organising frameworks relating to research dissemination. Thirty-three frameworks met our inclusion criteria, 20 of which were designed to be used by researchers to guide their dissemination activities. Twenty-eight included frameworks that were underpinned at least in part by one or more of three different theoretical approaches, namely persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory, and social marketing.

Our search strategy was deliberately broad, and we searched a number of relevant databases and other sources with no language or publication status restrictions, reducing the chance that some relevant studies were excluded from the review and of publication or language bias. However, we restricted our searches to health and social science databases, and it is possible that searches targeting for example the management or marketing literature may have revealed additional frameworks. In addition, this review was undertaken as part of a project assessing UK research dissemination, so our search for frameworks provided by funding agencies was limited to the UK. It is possible that searches of funders operating in other geographical jurisdictions may have identified other studies. We are also aware that the way in which we have defined the process of dissemination and our judgements as to what constitutes sufficient detail may have resulted in some frameworks being excluded that others may have included or vice versa. Given this, and as an aid to transparency, we have included the list of excluded papers as Additional File 2, Appendix 2 so as to allow readers to assess our, and make their own, judgements on the literature identified.

Despite these potential limitations, in this review we have identified 33 frameworks that are available and could be used to help guide dissemination planning and activity. By way of contrast, a recent systematic review of the knowledge transfer and exchange literature (with broader aims and scope) [61] identified five organising frameworks developed to guide knowledge transfer and exchange initiatives (defined as involving more than one way communications and involving genuine interaction between researchers and target audiences) [13–15, 62, 63]. All were identified by our searches, but only three met our specific inclusion criteria of providing sufficient dissemination process detail [13–15]. One reviewed methods for assessment of research utilisation in policy making [62], whilst the other reviewed knowledge mapping as a tool for understanding the many knowledge creation and translation resources and processes in a health system [63].

There is a large amount of theoretical convergence among the identified frameworks. This all the more striking given the wide range of theoretical approaches that could be applied in the context of research dissemination [64], and the relative lack of cross-referencing between the included frameworks. Three distinct but interlinked theories appear to underpin (at least in part) 28 of the included frameworks. There has been some criticism of health communications that are overly reliant on linear messenger-receiver models and do not draw upon other aspects of communication theory [65]. Although researcher focused, the included frameworks appear more participatory than simple messenger-receiver models, and there is recognition of the importance of context and emphasis on the key to successful dissemination being dependent on the need for interaction with the end user.

As we highlight in the introduction, there is recognition among international funders both of the importance of and their role in the dissemination of research [9]. Given the current political emphasis on reducing deficiencies in the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could be making and advocating more systematic use of conceptual frameworks in the planning of research dissemination.

Rather than asking applicants to briefly indicate how findings arising from their proposed research will be disseminated (as seems to be the case in the UK), funding agencies could consider encouraging grant applicants to adopt a theoretically-informed approach to their research dissemination. Such an approach could be made a conditional part of any grant application process; an organising framework such as those described in this review could be used to demonstrate the rationale and understanding underpinning their proposed plans for dissemination. More systematic use of conceptual frameworks would then provide opportunities to evaluate across a range of study designs whether utilising any of the identified frameworks to guide research dissemination does in fact enhance the uptake of research findings in policy and practice.

Summary

There are currently a number of theoretically-informed frameworks available to researchers that could be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity. Given the current emphasis on enhancing the uptake of knowledge about the effects of interventions into routine practice, funders could consider encouraging researchers to adopt a theoretically informed approach to their research dissemination.

References

Cooksey D: A review of UK health research funding. London: Stationery Office. 2006

Darzi A: High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. 2008, London: Department of Health

Department of Health: Best Research for Best Health: A new national health research strategy. 2006, London: Department of Health

National Institute for Health Research: Delivering Health Research. National Institute for Health Research Progress Report 2008/09. London: Department of Health. 2009

Tooke JC: Report of the High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness A report to Sir Liam Donaldson Chief Medical Officer. London: Department of Health. 2007

World Health Organization: World report on knowledge for better health: strengthening health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2004

Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N: Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006, 26: 13-24.

World Health Organization: Bridging the 'know-do' gap: meeting on knowledge translation in global health 10-12 October 2005. 2005, Geneva: World Health Organization

Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Wensing M, Durieux P, Légaré F, Nielson CP, Adily A, Ward JE, Porter C, Shea B, Grimshaw JM: Health research funding agencies' support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q. 2008, 86: 125-55.

Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I: Why promote the findings of single research studies?. BMJ. 2008, 336: 722-

Winkler JD, Lohr KN, Brook RH: Persuasive communication and medical technology assessment. Arch Intern Med. 1985, 145: 314-17.

Lomas J: Diffusion, Dissemination, and Implementation: Who Should Do What. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993, 703: 226-37.

Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, DiCenso A: A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health-care policy and practice. Online J Knowl Synth Nurs. 2002, 9: 7-

Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P: Development of a framework for knowledge translation: understanding user context. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003, 8: 94-9.

Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, McLeod CB, Abelson J, Knowledge Transfer Study G: How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers?. Milbank Q. 2003, 81: 221-48.

Wilson PM, Petticrew M, Calnan MW, Nazareth I: Does dissemination extend beyond publication: a survey of a cross section of public funded research in the UK. Implement Sci. 2010, 5: 61-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews. 2009, York: University of York, 3

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD's guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews. York: University of York. 1994

National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research: A Review of the Literature on Dissemination and Knowledge Utilization. Austin, TX: National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. 1996

Hughes M, McNeish D, Newman T, Roberts H, Sachdev D: What works? Making connections: linking research and practice. A review by Barnardo's Research and Development Team. Ilford: Barnardo's. 2000

Harmsworth S, Turpin S, TQEF National Co-ordination Team, Rees A, Pell G, Bridging the Gap Innovations Project: Creating an Effective Dissemination Strategy. An Expanded Interactive Workbook for Educational Development Projects. Centre for Higher Education Practice: Open University. 2001

Herie M, Martin GW: Knowledge diffusion in social work: a new approach to bridging the gap. Soc Work. 2002, 47: 85-95.

Scullion PA: Effective dissemination strategies. Nurse Res. 2002, 10: 65-77.

Farkas M, Jette AM, Tennstedt S, Haley SM, Quinn V: Knowledge dissemination and utilization in gerontology: an organizing framework. Gerontologist. 2003, 43 (Spec 1): 47-56.

Canadian Health Services Research Foundation: Communication Notes. Developing a dissemination plan Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation. 2004

Economic and Social Research Council: Communications strategy: a step-by-step guide. Swindon: Economic and Social Research Council. 2004

European Commission. European Research: A guide to successful communication. 2004, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities

Carpenter D, Nieva V, Albaghal T, Sorra J: Development of a Planning Tool to Guide Dissemination of Research Results. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation, Programs, Tools and Practices. 2005, Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 4:

Bauman AE, Nelson DE, Pratt M, Matsudo V, Schoeppe S: Dissemination of physical activity evidence, programs, policies, and surveillance in the international public health arena. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S57-S65.

Formoso G, Marata AM, Magrini N: Social marketing: should it be used to promote evidence-based health information?. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64: 949-53.

Zarinpoush F, Sychowski SV, Sperling J: Effective Knowledge Transfer and Exchange: A Framework. Toronto: Imagine Canada. 2007

Majdzadeh R, Sadighi J, Nejat S, Mahani AS, Gholami J: Knowledge translation for research utilization: design of a knowledge translation model at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008, 28: 270-7.

Friese B, Bogenschneider K: The voice of experience: How social scientists communicate family research to policymakers. Fam Relat. 2009, 58: 229-43.

Yuan CT, Nembhard IM, Stern AF, Brush JE, Krumholz HM, Bradley EH: Blueprint for the dissemination of evidence-based practices in health care. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010, 86: 1-16.

McGuire WJ: The nature of attitudes and attitude change. Handbook of social psychology. Edited by: Lindzey G, Aronsen E. 1969, Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 136-314.

McGuire WJ: Input and output variables currently promising for constructing persuasive communications. Public communication campaigns. Edited by: Rice R, Atkin C. 2001, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 22-48. 3

Lasswell HD: The structure and function of communication in society. The communication of ideas. Edited by: Bryson L. 1948, New York: Harper and Row, 37-51.

National Center for the Dissemination of Disability Research: Developing an Effective Dissemination Plan. 2001, Austin, Tx: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory (SEDL)

Freemantle N, Watt I: Dissemination: implementing the findings of research. Health Libr Rev. 1994, 11: 133-7.

Rogers EM: The diffusion of innovations. 1962, New York: Free Press

Rogers EM: Diffusion of innovations. 2003, New York, London: Free Press, 5

Kotler P, Zaltman G: Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. J Market. 1971, 35: 3-12.

Caplan N: The two-communities theory and knowledge utilization. Am Behav Sci. 1979, 22: 459-70.

Funk SG, Tornquist EM, Champagne MT: A model for improving the dissemination of nursing research. West J Nurs Res. 1989, 11: 361-72.

Lomas J: Teaching old (and not so old) docs new tricks: effective ways to implement research findings. 1993, CHEPA working paper series No 93-4. Hamiltion, Ont: McMaster University

Elliott SJ, O'Loughlin J, Robinson K, Eyles J, Cameron R, Harvey D, Raine K, Gelskey D, Canadian Heart Health Dissemination Project Strategic and Research Advisory Groups: Conceptualizing dissemination research and activity: the case of the Canadian Heart Health Initiative. Health Educ Behav. 2003, 30: 267-82.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane , Kyriakidou O, Peacock R: How to spread good ideas. A systematic review of the literature on diffusion, dissemination and sustainability of innovations in health service delivery and organisation. London: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO). 2004

Green LW, Orleans C, Ottoson JM, Cameron R, Pierce JP, Bettinghaus EP: Inferring strategies for disseminating physical activity policies, programs, and practices from the successes of tobacco control. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S66-S81.

Owen N, Glanz K, Sallis JF, Kelder SH: Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2006, 31 (1 Suppl): S35-S44.

Landry R, Amara N, Ouimet M: Determinants of Knowledge Transfer: Evidence from Canadian University Researchers in Natural Sciences and Engineering. J Technol Transfer. 2007, 32: 561-92.

Baumbusch JL, Kirkham SR, Khan KB, McDonald H, Semeniuk P, Tan E, Anderson JM: Pursuing common agendas: a collaborative model for knowledge translation between research and practice in clinical settings. Res Nurs Health. 2008, 31: 130-40.

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE: A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008, 34: 228-43.

Clinton M, Merritt KL, Murray SR: Using corporate universities to facilitate knowledge transfer and achieve competitive advantage: An exploratory model based on media richness and type of knowledge to be transferred. International Journal of Knowledge Management. 2009, 5: 43-59.

Mitchell P, Pirkis J, Hall J, Haas M: Partnerships for knowledge exchange in health services research, policy and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, 14: 104-11.

Ward V, House A, Hamer S: Developing a framework for transferring knowledge into action: a thematic analysis of the literature. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009, 14: 156-64.

Ward V, Smith S, Carruthers S, House A, Hamer S: Knowledge Brokering. Exploring the process of transferring knowledge into action Leeds: University of Leeds. 2010

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane , Bate P, Kyriakidou O: Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Millbank Q. 2004, 82: 581-629.

Wernerfelt B: A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Manage J. 1984, 5: 171-80.

Grant R: Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Manage J. 1996, 17: 109-22.

Joseph Rowntree Foundation: Findings: Linking research and practice. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2000

Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Waye Perry B: Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007, 85: 729-68.

Hanney S, Gonzalez-Block M, Buxton M, Kogan M: The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment. Health Res Policy Syst. 2003, 1: 2-

Ebener S, Khan A, Shademani R, Compernolle L, Beltran M, Lansang M, Lippman M: Knowledge mapping as a technique to support knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ. 2006, 84: 636-42.

Grol R, Bosch M, Hulscher M, Eccles M, Wensing M: Planning and studying improvement in patient care: the use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007, 85: 93-138.

Kuruvilla S, Mays N: Reorienting health-research communication. Lancet. 2005, 366: 1416-18.

Acknowledgements

This review was undertaken as part of a wider project funded by the MRC Population Health Sciences Research Network (Ref: PHSRN 11). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Paul Wilson is an Associate Editor of Implementation Science. All decisions on this manuscript were made by another senior editor. Paul Wilson works for, and has contributed to the development of the CRD framework which is included in this review. The author(s) declare that they have no other competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, design, and analysis of the review. All authors were involved in the writing of the first and all subsequent versions of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Paul Wilson is the guarantor.

Electronic supplementary material

13012_2010_305_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Appendix 1: Database search strategies. This file includes details of the database specific search strategies used in the review. (DOC 39 KB)

13012_2010_305_MOESM2_ESM.DOC

Additional file 2: Appendix 2: Full-text papers assessed for eligibility but excluded from the review. This file includes details of full-text papers assessed for eligibility but excluded from the review. (DOC 52 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, P.M., Petticrew, M., Calnan, M.W. et al. Disseminating research findings: what should researchers do? A systematic scoping review of conceptual frameworks. Implementation Sci 5, 91 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-91

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-91