Abstract

Problems related to alcohol consumption are priority public health issues worldwide and may compromise women’s health. The early detection of risky alcohol consumption combined with a brief intervention (BI) has shown promising results in prevention for different populations. The aim of this study was to examine data from recent scientific publications on the use of BI toward reducing alcohol consumption among women through a systematic review. Electronic searches were conducted using Web of Science, PubMed(Medline) and PsycInfo databases. In all databases, the term “brief intervention” was associated with the words “alcohol” and “women”, and studies published between the years 2006 and 2011 were selected. Out of the 133 publications found, the 36 scientific articles whose central theme was performing and/or evaluating the effectiveness of BI were included. The full texts were reviewed by content analysis technique. This review identified promising results of BI for women, especially pregnant women and female college students, in different forms of application (face-to-face, by computer or telephone) despite a substantial heterogeneity in the clinical trials analyzed. In primary care, which is a setting involving quite different characteristics, the results among women were rather unclear. In general, the results indicated a decrease in alcohol consumption among women following BI, both in the number of days of consumption and the number of doses, suggesting that the impact on the woman’s reproductive health and the lower social acceptance of female consumption can be aspects favorable for the effectiveness of BI in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems are considered public health priorities worldwide [1, 2]. There are significant gender differences regarding the development of problems caused by alcohol. Compared with men, women’s risk of alcohol use has a disproportionate effect on their lives and health, including consequences on reproductive function and pregnancy [3].

Initiatives aimed at the early detection of risky (hazardous and harmful) drinking have been shown to be effective in preventing alcohol-related social and health consequences [4, 5]. Developed for use in primary care, Brief Intervention (BI) has been found to be an effective and low-cost treatment alternative for alcohol use problems. Using self-help strategies, BI aims to promote a decrease in alcohol consumption among nondependent individuals, and in the case of dependence, to facilitate referral to specialized treatment programs [5]. This approach is used in the primary or secondary prevention of alcohol and drug use, which is focused on changing the patient’s behavior through time-limited assistance and is performed by professionals from different backgrounds [4, 6]. Given those characteristics, this approach has been considered a relevant practice in the context of public health.

Studies on BIs have demonstrated both its efficacy (ideal world) and effectiveness (real world), in different clinical settings [6–9]. Research suggests that the effectiveness of a BI in reducing problems caused by alcohol can be equal to or even higher than other interventions that require more time to be performed [4, 7–9]. There are also different ways of applying this type of intervention, which may vary from counseling sessions with a professional (face-to-face, by phone or online) to self-applied interventions with the aid of manuals or computer-based tools [10–14].

Despite the existence of variations in BI, it is grounded in social-cognitive theory [9] and commonly incorporates some elements of motivational interviewing [15], a behavioral change technique which helps individuals to recognize a problem and motivate them to change it. BI typically provides risky drinkers with feedback on their use, information on the adverse consequences of alcohol; information on the benefits of reducing intake; analysis of high risk situations for drinking and techniques to help moderate their consumption [4, 6, 9]. The approach also includes an emphasis on the individual’s responsibility for his/her own consumption, empathic attitude, counseling toward changing those behaviors based on the identification of strategies for interrupting or decreasing consumption and stimulus to the patient’s self-efficacy perception. Moreover, the setting of goals to be achieved and reassessed at follow-up sessions is common practice in this type of intervention [4, 6, 9, 16, 17].

Data from the WHO (World Health Organization) [18] indicate that alcohol consumption patterns significantly differ between men and women and among age, ethnic, religious and cultural groups, which are key aspects to be addressed in health care. A comprehensive and significant review on BIs in primary care concluded that this approach reduces alcohol consumption in men, but these findings do not extend to women; therefore, research on the most effective components of those interventions in this population is necessary [9]. Thus, the main objective of this study was to examine data from recent scientific publications on the use of BI toward reducing alcohol consumption among women through a systematic literature review.

Methods

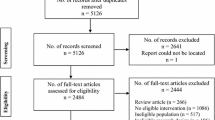

Online searches were performed using Web of Science, PubMed(Medline) and PsycInfo databases. The expression “brief intervention” was linked to the terms “alcohol” and “women” in all three databases, and studies published between 2006 and 2011 were selected.

Out of the 133 papers found, 97 were excluded upon a reading of their abstracts because they were proceeding papers, meetings, book chapters, dissertations, theoretical articles, literature reviews or because they did not address the subject of interest. The papers whose full text was not available in the English language were also disregarded. Most excluded studies consisted of cross-sectional studies that measured the prevalence of alcohol consumption but did not perform a BI, instead suggesting it as a key strategy to be evaluated in future studies. Thus, we included 36 articles that met the following inclusion criteria: a) performed and/or evaluated the effectiveness of a BI; b) performed a BI toward alcohol consumption (not other drugs); c) presented women as part of the studied sample.

The full texts were reviewed through a thematic and structural content analysis, undergoing several stages of data organization [19]. The first stage of analysis was a brief reading for general evaluation. Subsequently, the material exploration began through a vertical analysis of the data, thereby establishing categories and subcategories according to the most common topics found. The following categories of interest to the study were systematized: year and publishing journals, research design, samples with emphasis on women, tools for evaluating alcohol consumption, differentiated measurements of that consumption according to gender, setting where the intervention was performed, duration of sessions and main outcomes of the studies.

Two researchers performed the vertical analysis; however, in cases of disagreement as to the article categorization, a referee with experience in content analysis was defined and asked to reach a final consensus. A comparison and horizontalization of the categorization of each article was performed for a data overview as the final analysis stage. This phase consisted of joining and summing the frequency of categories and subcategories classified in each publication [19].

Results

Among the 36 articles included, 14 were published in 2006/2007 [16, 20–32], 10 in 2008/2009 [8, 11–14, 33–37] and 12 in 2010/2011 [3, 38–47]. The journals that published the most articles were the following: Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs (4) [8, 28, 36, 42] and Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research (4) [12, 27, 40, 47], which were followed by Addictive Behaviors (3) [16, 24, 43], Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (3) [22, 32, 37] and Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment (3) [20, 30, 46]. The vast majority of studies (28) were performed by North American institutions, while 4 studies were performed in Sweden [10, 11, 29, 39], 2 in Australia [14, 33], 1 in Switzerland [28] and 1 in Denmark [23]. Only 6 studies were not randomized clinical trials [10, 16, 25, 35, 43, 44].

The analysis of the samples of the 36 studies (Table 1) was aimed at highlighting the articles that performed BIs strictly on women or having them in majority. College students were the most studied population group (10) [14, 16, 22, 24, 32, 36–38, 41, 42], followed by pregnant women (8) [10, 13, 20, 25, 26, 30, 35, 45], inpatients (4) [8, 28, 31, 40], primary care patients (3) [23, 27, 39] and women at reproductive age (3) [21, 29, 47]. Considering the age of the study cohorts, the majority (16) of the articles presented a mean age under 30 years [12, 14, 16, 22, 24, 29, 35–38, 40–43],[45, 47], while 7 studies showed averages of 30–40 years [3, 11, 20, 21, 23, 28, 30] and 6 above 40 years [8, 31, 33, 39, 44, 46]. Seven studies [10, 13, 25–27, 32, 34], did not present information on the average age of the sample.

Regarding the intervention setting, most studies (23) were face-to-face. In 10 studies, the BI was performed online through a computer [13, 14, 25, 32, 38, 41, 43, 45],[47] and by telephone in 3 [11, 27, 39]. Furthermore, most interventions reported in the articles were performed in a single session (19) [3, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16, 20–26, 30],[31, 41, 45–47] , with the session length varying between 10 and 30 minutes in 10 studies [8, 13, 20, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31],[45, 46].

The timeline follow-back (TLFB) was one of the most used tools for measuring alcohol consumption and was adopted in 12 of the empirical studies analyzed [8, 22, 24, 28–30, 33, 34, 36, 38],[45, 47]. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was also applied in 12 studies [3, 10, 11, 14, 16, 23, 29, 31],[33, 37, 43, 44]. The T-ACE (Tolerance, Annoyed, Cut Down, Eye-Opener), was used in 7 studies [12, 20, 21, 30, 45–47]. The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ) was used in 6 studies [16, 22, 32, 37, 38, 41].

Of note, among the studies simultaneously focusing on men and women (21), the use of different measurements to characterize female alcohol consumption was identified in 14 of the studies examined, and there were variations in the distinctions adopted between men and women. Among the 5 studies that adapted the AUDIT score, 1 used 7 [16] and 3 studies used 6 [11, 43, 44] as the female cut-off point, while maintaining 8 as the male cut-off point. In contrast, the study performed on college students with alcohol consumption problems [37] used 10 as the cut-off point in that tool for both genders.

The differentiation most frequently found in the articles (in 7 of them) refers to the heavy episodic drinking on a single occasion, as follows: 4 or more doses for women and 5 or more doses for men. Regarding a weekly limit, 3 studies considered a female consumption of 7 or more doses for the period, while the male consumption equivalent was 14 or more weekly doses [8, 28, 38].

Analyzing the outcomes obtained with the BIs it was observed that out of the 36 studies analyzed, 12 of them showed no gender distinctions in the results [14, 16, 22, 24, 28, 31, 36, 40–44]. The 24 articles with separate results for women were classified in 3 groups (Tables 2, 3 and 4) according to the following study specificities: the first group comprised the studies whose main aim was to assess the effectiveness of BI in decreasing alcohol consumption; the second group assessed secondary outcomes of BI; and the third group compared different types of interventions.

Table 2 shows the 16 clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of a BI in decreasing alcohol consumption, with specific results for women. Among the 9 studies whose sample was exclusively composed of women [3, 12, 21, 25, 26, 29, 45–47], 6 of them obtained positive results [3, 12, 25, 26, 29, 45] with respect to the expected outcomes, while in 3 [21, 46, 47], the effectiveness of the BI could not be demonstrated (and the result was classified as neutral). The other 7 studies had samples comprising both genders, and the results found were positive in 5 of them, as follows: 1 study [11] found no significant differences between the genders and was effective for both men and women; and in 4 of them [8, 32, 38, 39], more changes were found in women than in men. Conversely, 2 articles reported better results with a male audience, with the female consumption in 1 study increasing following the BI [23] and the result being classified as negative, while in the other study [27], the effectiveness of the BI was not clear for women.

Table 3 shows four studies [20, 30, 34, 35] which indirectly assessed the impact of the BI on other phenomena in addition to alcohol use (i.e., depressive symptoms and stages of motivation toward change). Although BI has been performed in all these studies, the assessment of its effectiveness was not the main research focus.

Table 4 shows another 4 studies [10, 13, 33, 37] that were aimed at comparing different types of interventions. In all these studies, the BI can be considered effective in decreasing alcohol consumption among women, regardless of the way in which it was performed.

Discussion

This literature review identified promising results of BI for women, especially pregnant women and female college students, in different forms of application (face-to-face or by computer or telephone) despite a substantial heterogeneity in the clinical trials analyzed. In primary care, which is a setting involving quite different characteristics, the results among women were rather unclear.

It is worth noting that most empirical studies with a sample exclusively composed of women addressed pregnant women, given the impact of alcohol consumption on reproductive issues. In general, these studies indicate that BI was effective in decreasing alcohol consumption among participants of the experimental group. However, the control group participants also tended to reduce their consumption, a finding that coincides with the previous review on BI during pregnancy [48]. It is believed that pregnant women are usually highly motivated toward decreasing alcohol consumption and that the change in context brought by pregnancy provides an opportunity to break the drinking habit [17, 48, 49]. Therefore, given their condition, obstetric patients would already have a strong motivation to stop or decrease alcohol consumption, favoring the effectiveness of the intervention.

In this sense, studies with pregnant women generally address the incidence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), which includes a myriad of biological and behavioral disorders and may be regarded as the best-known consequence of alcohol drinking during pregnancy [13, 25, 26, 45]. Because a substantial number of women identify their pregnancy after a few months Floyd et al. [17] indicated the need to develop universal strategies aimed at alcohol consumption among women of reproductive age in different contexts and cultures, instead of only among obstetric patients. Such strategies could prevent the alcohol-related harms in the early months of pregnancy, when it is still unknown. Although some studies have indicated that light drinking during pregnancy is not associated to cognitive or behavioral problems in childhood [50–52], it remains unclear what level of alcohol consumption is safe during this phase and how this consumption can affect individual susceptibility [52].

It is worth noting that seven articles focused on non-pregnant female populations [3, 12, 21, 29, 34, 46, 47]. However, each study was performed on women with unusual health conditions and socio-demographic characteristics. There was a decrease of the participants’ consumption in all studies.

With regard to alcohol consumption among college students, it should be noted that this group is in a phase of life with specific characteristics, such as their age and the social activities related to this stage of life, that are associated with excessive drinking. Thus, alcohol use may cease upon graduation or may continue, thereby leading to serious problems. In this context BI is a key prevention strategy [53].

Among the studies analyzed involving college students, all results indicated a decrease in the levels of consumption in both genders [14, 16, 22, 24, 32, 36–38, 41, 42], and the studies that showed gender differences pointed to better effects among female participants [32, 37, 38]. These data on BI with college students, especially the best results on female audiences, were also indicated in a review study on the subject. It highlighted that online interventions have been effective among college students and that women seem more involved in that type of approach, which can be related to the anonymity provided in the face of the stigma regarding alcohol consumption problems in the female population [53].

The context of primary health care, which is considered to be strategic for the detection and prevention of alcohol use as a function of its scale of operation [1], was addressed in only three studies [23, 27, 39], reaching different results with regard to the female audience. Lin et al. [39] found a higher probability of decreasing consumption in Hispanic or non-Caucasian women following a BI by telephone in a sample composed of men and women with a mean age of 68 years. In addition, by applying a BI by telephone, Brown et al. [27] obtained a statistically significant decrease in the consumption of men only, while women of the intervention and control groups (predominantly Caucasian and aged between 20 and 39 years) showed a considerable reduction in alcohol consumption, albeit with no significant difference between the female groups. The authors believe that the initial measurement, which involved several questions about alcohol consumption, even addressing aspects of readiness to change that type of behavior, may have influenced the changes observed in the studied women.

In contrast, the study conducted by Beich et al. [23] focused on primary health care in Denmark (contrary to previous studies performed in the USA) and observed that women appear to show more defensive reactions than men when faced with a BI and may be more sensitive to criticism of their alcohol consumption. That study found no satisfactory results of a BI application in that context because both genders showed a modest increase of consumption during the follow-up.

The study by Kaner et al. [9] emphasized the need to investigate the applicability of BI in the actual context of primary care, considering issues relevant to that setting including the following: unawareness/non-receptiveness of professionals and patients to address issues related to alcohol consumption, time to implement the tool, professional training toward using that approach and the routine of that type of service. The difficulty of implementing a BI in primary care requires that better strategies be identified to adapt practices to the specific circumstances of the context [54].

With regard to the specificities of alcohol consumption in men and women, the WHO [18] indicates that biological factors, including a lower body weight and muscle-fat ratio contribute to making the substance effects appear faster/more intensely in women than in men. Most studies analyzed adopted different criteria to characterize the male and female consumption as risky. However, there seems to be no consensus regarding the quantification of this difference. Most likely, the variation in cut-off points and difference in doses in the tools results from differences in alcohol concentration, which varies from country to country.

Regarding the diversity of tools used for screening, there was a tendency to use more than one tool to characterize alcohol consumption in the samples studied, and the AUDIT and TLFB were the most frequently adopted in the samples analyzed. Beich et al. [23] thought that the exclusive use of the AUDIT as a tool to recruit at-risk consumers might not suffice to identify homogeneous samples regarding alcohol use. Thus, future studies involving two or three stages of measurement/identification of consumption patterns may show better results of BI effectiveness. Carey et al. [22] observed a decrease in alcohol consumption among college students based on the exclusive application of a TLFB by interview, recommending that the same be used as a BI procedure.

The findings of that study indicating different procedures for implementing BI, including the number and duration of sessions, converge with the summary performed by Nilsen [48]. According to the author, BIs are not homogenous entities but, instead, are a set of practices with common principles. Floyd et al. [29] and Kaner et al.[9] indicated the need to identify which components of the BI are most effective for women in subsequent studies.

The identification of studies comparing interventions and assessing the impact of a BI on various aspects of alcohol consumption indicates the connection between this problem and other key variables, in addition to the pursuit of improvement of interventions. In this sense, a key aspect found [34], which still requires further research, is the indirect impact of a BI on psychosocial phenomena and health consequences that may be linked to alcohol consumption in women (such as depression and domestic violence, among others), suggesting the expansion of its preventive approach. The use of a BI with a focus on other problems has shown promising results, but the evidence is still lacking [54].

The limitations of this study include the limited addition of recent studies (last five years) and the option for a descriptive review without performing a meta-analysis. Given the clinical, methodological and statistical heterogeneity of the studies, a more qualitative approach was used to compare findings in this systematic review. Moreover, because the studies reviewed were performed in developed countries, there is a need to produce cross-cultural studies and studies in developing countries to address the socio-cultural aspects related to alcohol consumption and the effectiveness of a BI in different contexts.

Conclusions

The studies assessing the effectiveness of a BI were performed primarily in clinical settings and healthcare services and, in general, reported a decrease in alcohol consumption in the sample studied, both in the number of days of consumption and in the number of doses (or both). Studies on women in community samples in different cultures could represent an alternative to the difficulties of implementation in health services and provide further data on the effectiveness for this population. The literature reports reviewed suggest that the impact on women’s reproductive health and the lower social acceptance of female consumption are aspects favoring the effectiveness of a BI for this audience.

To the extent that preventing female consumption is critical in terms of public health, public policies that encourage the implementation of integrated screening and BI in clinical practice may have a substantial impact on reducing alcohol related harms, both at individual and population levels, especially in developing countries.

Authors’ information

CG is a PhD student from the Department of Psychobiology of Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP). FB is a PhD student from the Department of Psychology of Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF). TR and LM are associate professors from the Department of Psychology of UFJF. AN is an associate professor from the Department of Psychobiology of UNIFESP.

Abbreviations

- BI:

-

Brief intervention

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol use disorders identification test

- TLFB:

-

Time-line followback

- DDQ:

-

Daily drinking questionnaire (DDQ)

- FASD:

-

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

References

Humeniuk RE, Henry-Edwards S, Ali RL, Poznyak V, Monteiro M: The ASSIST-Linked Brief Intervention for Hazardous and Harmful Substance use: Manual for use in Primary Care. 2010, Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse

World Health Organization (WHO): Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. 2011, Geneva

Begun AL, Rose SJ, LeBel TP: Intervening with women in jail around alcohol and substance abuse during preparation for community reentry. Alcohol Treat Q. 2011, 29: 453-478. 10.1080/07347324.2011.608333.

Babor TF, Mcree GB, Kassebaum MA, Grimaldi PL, Ahmed K, Bray J: Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management. Subst Abuse. 2007, 28: 7-30. 10.1300/J465v28n03_03.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG: AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. 2001, World Health Organization, Geneva: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care

Nilsen P, Kaner E, Babor TF: Brief intervention, three decades on. An overview of research findings and strategies for more widespread implementation. Nordisk Alkohol Nark. 2008, 25: 453-469.

Formigoni MLOS, Ronzani TM: Secretaria Nacional Antidrogas – Senad. (Org.). Sistema Para a Detecção do Uso Abusivo e Dependência de Substâncias Psicoativas – SUPERA. Volume 4. Efetividade e Relação Custo-Benefício das Intervenções Breves. 2008, Brasília: Senad – Governo Federal, 58-63. 2

Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM: Some medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use may benefit from brief intervention. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009, 70: 426-435.

Kaner EFS, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, Heather N, Saunders J, Burnand B: Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations [review]. Cochrane Libr. 2008, 1: 1-76.

Nilsen P, Holmqvist M, Bendtsen P, Hultgren E, Cedergren M: Is questionnaire-based alcohol counseling more effective for pregnant women than standard maternity care?. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010, 19: 161-167. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1417.

Eberhard S, Nordstrom G, Hoglund P, Ojehagen A: Secondary prevention of hazardous alcohol consumption in psychiatric out-patients: a randomised controlled study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009, 44: 1013-1021. 10.1007/s00127-009-0023-7.

Fleming MF, Lund MR, Wilton G, Landry M, Scheets D: The healthy moms study: the efficacy of brief alcohol intervention in postpartum women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008, 32: 1600-1606. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00738.x.

Armstrong MA, Kaskutas LA, Witbrodt J, Taillac CJ, Hung YY, Osejo VM, Escobar GJ: Using drink size to talk about drinking during pregnancy: a randomized clinical trial of early start plus. Soc Work Health Care. 2009, 48: 90-103. 10.1080/00981380802451210.

Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML, Herbison P: Randomized controlled trial of web-based alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 530-536. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.109.

Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change. 2002, New York: Guilford Press

Martens MP, Cimini MD, Barr AR, Rivero EM, Vellis PA, Desemone GA, Horner KJ: Implementing a screening and brief intervention for high-risk drinking in university-based health and mental health care settings: reductions in alcohol use and correlates of success. Addict Behav. 2007, 32: 2563-2572. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.005.

Floyd RL, Weber MK, Denny C, O’Connor MJ: Preventions of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009, 15: 193-199. 10.1002/ddrr.75.

World Health Organization (WHO): Gender, Health and Alcohol use. 2005, Geneva: WHO Department of Gender, Women and Health

Bardin L: Análise de Conteúdo (content analysis). Lisboa: Edições. 1977, 70: 95-150.

Chang G, McNamara TK, Wilkins-Haug L, Orav EJ: Brief intervention for prenatal alcohol use: the role of drinking goal selection. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006, 31: 419-424. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.016.

Chang G, McNamara TK, Haimovici F, Hornstein MD: Problem drinking in women evaluated for infertility. Am J Addict. 2006, 15: 174-179. 10.1080/10550490500528639.

Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM: Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006, 74: 943-954.

Beich A, Gannik D, Saelan H, Thorsen T: Screening and brief intervention targeting risky drinkers in Danish general practice - a pragmatic controlled trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007, 42: 593-603. 10.1093/alcalc/agm063.

Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH: Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: a randomized factorial study. Addict Behav. 2007, 32: 2509-2528. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018.

Witbrodt J, Kaskutas LA, Diehl S, Armstrong MA, Escobar GJ, Taillac C, Osejo V: Using drink size to talk about drinking during pregnancy: early start plus. J Addict Nurs. 2007, 18: 199-206. 10.1080/10884600701699420.

O’Connor MJ, Whaley SE: Brief intervention for alcohol use by pregnant women. Am J Public Health. 2007, 97: 252-258. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077222.

Brown RL, Saunders LA, Bobula JA, Mundt MP, Koch PE: Randomized-controlled trial of a telephone and mail intervention for alcohol use disorders: three-month drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007, 31: 1372-1379. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00430.x.

Gmel G, Daeppen JB: Recall bias for seven-day recall measurement of alcohol consumption among emergency department patients: implications for case-crossover designs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007, 68: 303-310.

Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM: Preventing alcohol-exposed pregnancies: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2007, 32: 1-10.

Chang G, McNamara T, Wilkins-Haug L, Orav EJ: Stages of change and prenatal alcohol use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007, 32: 105-109. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.003.

Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM: Brief intervention for medical inpatients with unhealthy alcohol use - a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 146: 167-176. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00005.

Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Mallett KA, Lostutter TW, Cronce JM, Feeney M, Neighbors C: Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007, 75: 285-293.

Baker AL, Kavanagh DJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Hunt AS, Lewin TJ, Carr VJ, Connolly J: Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: short-term outcome. Addiction. 2009, 105: 87-99.

Fleming MF: The effect of brief alcohol intervention on postpartum depression. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2009, 34: 297-302. 10.1097/01.NMC.0000360422.06486.c4.

Yonkers KA, Howell HB, Allen AE, Ball AS, Pantalon MV, Rounsaville BJ: A treatment for substance abusing pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009, 12: 221-227. 10.1007/s00737-009-0069-2.

Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, Mullett N, O’Brien MC: Alcohol screening and brief intervention in a college student health center: a randomized controlled trial. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009, 16: 131-141.

Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto AS: Computer versus in-person intervention for students violating campus alcohol policy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009, 77: 74-87.

Bingham CR, Barretto AI, Walton MA, Bryant CM, Shope JT, Raghunathan TE: Efficacy of a web-based, tailored, alcohol prevention/intervention program for college students: initial findings. J Am Coll Health. 2010, 58: 349-356. 10.1080/07448480903501178.

Lin JC, Karno MP, Tang LQ, Barry KL, Blow FC, Davis JW, Ramirez KD, Welgreen S, Hoffin M, Moore AA: Do health educator telephone calls reduce at-risk drinking among older adults in primary care?. J Gen Intern Med. 2010, 25: 334-339. 10.1007/s11606-009-1223-2.

Field C, Caetano R: The role of ethnic matching between patient and provider on the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions with Hispanics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010, 34: 262-271. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01089.x.

Martens MP, Kilmer JR, Beck NC, Zamboanga BL: The efficacy of a targeted personalized drinking feedback intervention among intercollegiate athletes: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010, 24: 660-669.

Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Grossberg PM, Mundt MP, Brown D, Wiegel JR, Zakletskaia LI, Saewyc EM: Brief physician advice for heavy drinking college students: a randomized controlled trial in college health clinics. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010, 71: 23-31.

Sinadinovic K, Berman AH, Hasson D, Wennberg P: Internet-based assessment and self-monitoring of problematic alcohol and drug use. Addict Behav. 2010, 35: 464-470. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.021.

Ahacic K, Allebeck P, Thakker KD: Being questioned and receiving advice about alcohol and smoking in health care: associations with patients’ characteristics, health behavior, and reported stage of change. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2010, 5: 1-11. 10.1186/1747-597X-5-1.

Tzilos GK, Sokol RJ, Ondersma SJ: A randomized phase I trial of a brief computer-delivered intervention for alcohol use during pregnancy. J Womens Health. 2011, 20: 1517-1524. 10.1089/jwh.2011.2732.

Chang G, Fisher NDL, Hornstein MD, Jones JA, Hauke SH, Niamkey N, Briegleb C, Orav EJ: Brief intervention for women with risky drinking and medical diagnoses: a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011, 41: 105-114. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.011.

Delrahim-Howlett K, Chambers CD, Clapp JD, Xu RH, Duke K, Moyer RJ, Van Sickle D: Web-based assessment and brief intervention for alcohol use in women of childbearing potential: a report of the primary findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011, 35: 1331-1338. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01469.x.

Nilsen P: Brief alcohol intervention to prevent drinking during pregnancy: an overview of research findings. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 21: 496-500. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332a74c.

Keough VA, Jennrich JA: Including a screening and brief alcohol intervention program in the care of the obstetric patient. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009, 38: 715-722. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01073.x.

Robinson M, Oddy WH, McLean NJ, Jacoby P, Pennell CE, Klerk NH, Zubrick SR, Stanley FJ, Newnham JP: Low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and risk to child behavioural development: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2010, 117: 1139-1150. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02596.x.

Kelly Y, Sacker A, Gray R, Kelly J, Wolke D, Head J, Quigley MA: Light drinking during pregnancy: still no increased risk for socioemotional difficulties or cognitive deficits at 5 years of age?. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012, 66: 41-48. 10.1136/jech.2009.103002.

Kelly Y, Iacovou M, Quigley MA, Gray R, Wolke D, Kelly J, Sacker A: Light drinking versus abstinence in pregnancy - behavioural and cognitive outcomes in 7-year-old children: a longitudinal cohort study. BJOG. 2013, 1-8. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12246

Kelly-Weeder S: Binge drinking in college-aged women: framing a gender-specific prevention strategy. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008, 20: 577-584. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00357.x.

Gual A, Sabadini MBA: Implementing alcohol disorders treatment throughout the community. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011, 24: 203-207. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459256.

Acknowledgments

This study was developed with support from the following agencies: São Paulo Research Foundation (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP) (Processes No.: 2010/51094-7 and No.: 2010/51837-0) and Research Incentive Fund Association (Associação Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa - AFIP). The authors would like to thank Mayla Diniz and Aline Vaz for their contributions in the collection and organization of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CG and FB collected, analyzed, and categorized the data as well as wrote the article; TR served as a consultant for subject- and text-reviewing procedures; LL judged the content analysis and supervised the writing of the text; AN supervised the methodological design and the writing of the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebara, C.F.d.P., Bhona, F.M.d.C., Ronzani, T.M. et al. Brief intervention and decrease of alcohol consumption among women: a systematic review. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 8, 31 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-8-31

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-8-31