Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of perceived stress, depressive symptoms and religiosity with frequent alcohol consumption and problem drinking among freshmen university students from five European countries.

Methods

2529 university freshmen (mean age 20.37, 64.9% females) from Germany (n = 654), Poland (n = 561), Bulgaria (n = 688), the UK (n = 311) and Slovakia (n = 315) completed a questionnaire containing the modified Beck Depression Inventory for measuring depressive symptoms, the Cohen’s perceived stress scale for measuring perceived stress, the CAGE-questionnaire for measuring problem drinking and questions concerning frequency of alcohol use and the personal importance of religious faith.

Results

Neither perceived stress nor depressive symptoms were associated with a high frequency of drinking (several times per week), but were associated with problem drinking. Religiosity (personal importance of faith) was associated with a lower risk for both alcohol-related variables among females. There were also country differences in the relationship between perceived stress and problem drinking.

Conclusion

The association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms on the one side and problem drinking on the other demonstrates the importance of intervention programs to improve the coping with stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol use during early adulthood presents a serious public health problem in many countries [1, 2]. Studies have shown that heavy drinking and related problems are prevalent among young people, regardless of whether they attend college or not [3]. The majority of studies have found higher rates of alcohol-related problems in students compared to non-students [4–6]. In contrast, a recent study showed that college students drink less frequently than their non-college peers, but when students do drink, they tend to drink in greater quantities than non-students [7]. Among university students, first year freshmen display particularly high levels of alcohol consumption [8]. On the one hand, first year at university is a developmental transition to new responsibilities in absence of well-established networks of social support. On the other hand, it also represents freedom, liberty and fewer restrictions due to living away from parents [9]. Both aspects can increase the use of alcohol among students.

Generally, alcohol consumption has been linked to mental health problems e.g. perceived stress or depressive symptoms [10–15]. Depressive symptoms (based on DSM-IV) include sadness, anxiety or empty feelings; decreased energy; loss of interest in usual activities; sleep disturbances; weight gain/loss; feelings of worthlessness; suicidal thoughts; difficulty in concentrating or making decisions. Tension reduction theory contends that tension-producing circumstances (i.e. stressors) could lead to increased drinking [16–18]. As alcohol is perceived to reduce tension high levels of stress are therefore associated with drinking [19, 20], and depressive symptoms might also result in increased alcohol consumption [21]. Indeed, college students consume alcohol to: potentially relax or relieve tension; celebrate; feel comfortable with the opposite gender; as a reward for working hard; and to get away from troubles [22].

Religiosity is involved in the coping processes against stress and depressive symptoms [23, 24]. Religious coping entails dealing with stress, which involves a religious perspective. Such religious coping includes prayer, congregational support, pastoral care, and religious faith [25]. An alternative value system, which could be part of religious coping, may also improve the coping mechanism with respect to alcohol drinking behavior. The ‘net’ effects of the academic, social or economic stressors on student wellbeing might well depend on the extent of availability of coping resources in order to ‘buffer and balance’ the stress. Certainly, studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship between religiosity and alcohol use. For instance, students who reported that “religion is important in my life” had a lower frequency of heavy drinking in Nova Scotia, Canada [26] and in the USA [27, 28]. Similarly, American students who used religious coping tended to drink less alcohol [29]. Such evidence suggested that religiosity could be a potential confounder or even factor that modifies the association between mental health problems and alcohol consumption.

University students in various Eastern and Western European countries differ in terms of the reported levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms [30], alcohol consumption frequency, and the proportions of students with problematic alcohol use [1, 31]. Based on past history, there are still differences between countries of Eastern and Western Europe in terms of social life, health knowledge/literacy, individual habits, sense of power/powerlessness over health, and health-related lifestyles [32]. Such lifestyle factors have been suggested to contribute to differences in health and well-being across Western and Eastern Europe [33]. Further, given the different religious traditions with majority status in each country, personal religiosity has a potentially different association with alcohol consumption across the countries.

Although the problem of alcohol use among university students is evident almost globally [34–38], comparative studies using the same alcohol measures, identical mental health indicators and similar methodologies remain limited across countries. The current study bridges this gap by employing the same measures and identical indicators of alcohol consumption, depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and religiosity across five Eastern and Western European countries. For three of the five countries (Germany, Bulgaria and Poland), descriptive results of alcohol consumption [31] and of depressive symptoms and perceived stress [39] have been published recently. However, the associations between alcohol consumption and depressive symptoms and perceived stress were not assessed.

Aim of the study

The aim of the current study was to assess the associations of perceived stress and depressive symptoms with frequency of alcohol use and problem drinking among university students from five European countries, as well as to examine the role of religiosity for these associations. The specific objectives of the study were to:

· Assess whether perceived stress is associated with a high alcohol use frequency and problem drinking and whether this association differs by country and/or by sex. It was hypothesized that a higher level of perceived stress would be associated with more frequent alcohol use and problem drinking.

· Assess whether depressive symptoms are associated with high alcohol use frequency and problem drinking. It was hypothesized that a higher level of depressive symptoms will be associated with more frequent alcohol use and problem drinking.

· For both the above objectives, the role of religiosity was examined. It was hypothesized that religiosity modifies the associations between perceived stress or depressive symptoms on the one hand, and the frequency of alcohol use and problem drinking on the other.

Methods

Sample

The analysis described in this paper is based on data collected among university students in five countries from Western and Eastern Europe as part of the Cross-National Student Health Study (CNSHS) [40]. The participating universities were selected on basis of personal contacts of the researchers. These included: Bielefeld University in Bielefeld, Germany; the Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland; the University of Sofia, Sofia, Bulgaria; the University of Gloucestershire, United Kingdom; and, three universities in Kosice, Slovakia – PJ. Safarik University, the University of Veterinary Medicine and the Technical University. The campuses of all participating universities are situated in urban environments and alcohol consumption was not restricted on the campuses. The survey was conducted in Germany, Bulgaria and Poland (May 2005), in the UK (May 2007) and in Slovakia (May 2008).

A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to first-year students during regular classes of courses which were selected in order to obtain about one third of the sample each from the natural sciences, the social sciences, and business and law. In the UK and Slovakia, students cross all years were sampled, but only first year students were included in the current analysis. The overall response rate was 74% and the final sample included 2529 students. In order to increase the accuracy of self-reports, students were assured that their answers would remain confidential, and data protection was observed at all times.

Informed consent and ethics

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. Students were informed that by completing the questionnaire they were providing their informed consent to participate. They were also informed that they could terminate the participation at any point while filling out the questionnaire. The permission to conduct the study was granted by the participating institutions: Bielefeld University in Bielefeld, the Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, the University of Sofia, the University of Gloucestershire, the University of PJ Safarik, the University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Kosice and the Technical University of Kosice.

Measures

The questionnaire was developed in German and then translated into Polish, Bulgarian, English and Slovak using two independent forward translations for each language. The research team reviewed any cases of disagreement and the authors familiar with the respective languages (usually native speakers) made final decisions. The translations focused on and ensured the equivalence of meaning [41], and the assessment of the same attributes/features in each cultural group/country [42], as cross-cultural and cross-language equivalence require attention [43].

Frequency of alcohol consumption

Frequency of alcohol consumption was measured using the question: “Over the past three months how often have you drunk alcohol, for example, beer?” The response options were: “never,” “once a week or less,” “once a week,” “a few times each week,” “every day,” “a few times each day”. Abstainers were excluded from the analyses. For the purpose of analysis, this variable was dichotomised into “Low” (drinking once a week or less) versus “High” (drinking several times per week).

Problem drinking

In order to gather data on problem drinking we included an alcoholism-screening test, the CAGE test [44]. CAGE is a brief screening instrument comprising four short questions: “Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?”; “Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?”; “Have you ever felt bad or g uilty about your drinking?”; and, “Have you ever had a drink in the morning to get rid of a hangover?” Each question is answered with either “yes” or “no.” Two or three affirmative answers suggest problem drinking, while four positive responses indicate serious suspicion of alcohol dependence [44]. Respondents were classified as non-problem drinkers (<2 positive answers) and problem drinkers (≥2 positive answers).

Demographic and economic variables

Students’ sex and age were based on individuals’ self-reports in the survey. Respondents’ subjective financial situation was measured by a single item: “How sufficient is your income?”, with a 4-point response scale ranging from 1 = ‘totally sufficient’ to 4 = ‘not sufficient at all’). To assess religion, the students were asked “What is your religion?”. They could chose among Christian, Islamic, other and none and in a second step specify the denomination of Christianity or Islam. In Slovakia, there was just one question with the three major Christian denominations, other religions and none as response options.

Perceived stress

This concept was measured with the four-item version of the Cohen’s perceived stress scale (PSS). PSS-4 is an economical and simple psychological instrument that measures the degree to which situations in one’s life over the past month are appraised as stressful [45]. The questions are of a general nature and items are designed to detect how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives, e.g. “How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”; and, “How often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems?”. Students responded on a five-point scale (0 = “never”, 1 = “almost never”, 2 = “sometimes”, 3 = “fairly often”, 4 = “very often”). Items were recoded so that higher scores indicated more perceived stress. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.74 (Germany), 0.75 (Poland), 0.67 (Bulgaria), 0.50 (UK) and 0.54 (Slovakia). The PSS score was obtained by summing up answers to individual questions.

Depressive symptoms

These were measured using a modified version of the Beck Depression Inventory (M-BDI) [46, 47]. Students were asked to describe how often they experienced 20 depressive feelings during the past few days with 6-point scale responses (from 0=”never” to 5 = “almost always”). The M-BDI score is obtained by summing up answers to individual questions. The authors of the M-BDI have demonstrated its construct validity and measurement equivalence as compared to the original BDI, and provided a cut-off score (at 35 points) for screening for clinically relevant depressive symptoms. The scale showed good to acceptable levels of reliability in all participating countries. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.90 (Germany), 0.92 (Poland), 0.87 (Bulgaria), 0.92 (UK) and 0.89 (Slovakia).

Religiosity (personal importance of religious faith)

From the many options available to measure formal and informal religiosity [48], we prioritised the assessment of the personal importance of religious faith as a measure of religiosity. Participants were asked about the extent that they agreed/disagreed with the following statement: "My religion is very important for my life”. Response options (1 = “strongly disagree”, 2 = “somewhat disagree”, 3 = “neither agree nor disagree”, 4 = “somewhat agree” and 5 = “strongly agree”) were subsequently dichotomised into two categories: ‘low importance of religious faith’ (values 1, 2 and 3) and ‘high importance of religious faith’ (values 4 and 5).

Statistical analysis

Listwise deletion was performed for handling missing data. Descriptive analysis of alcohol consumption, problem drinking and other studied variables was undertaken separately for each country. In the next step, the association between stress or depressive symptoms on the one side and frequency of drinking or problem drinking on the other was analysed in four separate multivariable logistic regression models. All models included sex, country, perceived sufficiency of income and personal religiosity. Additionally, all two-way interactions and three-way interactions were assessed. Only significant interactions were reported and included in final tables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 16, findings were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Significance level was set at p <0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the sample

The main characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Across the five countries, the majority of participants were females, with relatively higher proportions of female students in the Slavic countries. Slovakian students were the youngest, followed by students from Bulgaria, Poland, the UK, and Germany. Because of the relative small age variability within the countries and a higher variability between the countries, no adjustment for age was performed in the subsequent analyses. About 59.3% of the UK freshmen drank alcohol once a week or more often, followed by Bulgaria (33.6%), Germany (26.9%), Slovakia (15.1%) and Poland (12.2%). Problem drinking (two or more positive responses in CAGE) was found in 22.1% of UK students, followed by Slovakia (21.2%), Germany (17.0%), Bulgaria (13.6%) and Poland (11.8%). Importance of religious faith was highest among Polish participants followed by Slovakian, UK, Bulgarian and German participants. As expected, there was a substantial variation in students’ religions by country, with 21% of students stating no religion in Slovakia, 15.7% in Bulgaria, 12.1% in Germany and only 1.0% in Poland (data for the UK were not available). Among those who stated religion, most common was Christianity, but there were substantial differences in denominations, with Catholics being most common in Poland and Slovakia, Orthodox Christians in Bulgaria and Protestants in Germany.

Subjective perception of sufficiency of income was similar across the countries, with highest scores in the UK and Bulgaria and lowest in Slovakia and Germany. Mean PSS scores were highest in Slovakia followed by Bulgaria, Poland, Germany and the UK. The M-BDI scores were highest for the Bulgarians followed by Poles, Slovaks, Germans and finally the UK students.

Association between perceived stress and high frequency of alcohol consumption and problem drinking

Perceived stress was not associated with high frequency of drinking, but was associated with problem drinking after adjusting for sex, country, perceived sufficiency of income and importance of religious faith (Table 2). There was a significant interaction between sex and importance of religious faith: For both, the high frequency of drinking and problem drinking, females had a lower risk, additionally, the protective effects of high importance of religious faith were stronger among females than males. The association between perceived stress and problem drinking differed across the studied countries, with less pronounced effects in Germany and Slovakia and more pronounced effects in the UK. The interaction between the importance of religious faith and perceived stress was not significant; hence, there was no evidence that importance of religious faith modifies the relationships between perceived stress and high frequency of alcohol consumption or problem drinking.

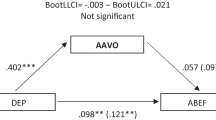

Association between depressive symptoms and high frequency of alcohol consumption and problem drinking

Depressive symptoms were not associated with high frequency of drinking, but were associated with problem drinking after adjusting for sex, country, perceived sufficiency of income and importance of religious faith (Table 3). Similarly to perceived stress, there was a significant interaction between sex and importance of religious faith for both, the high frequency of drinking and problem drinking. The association between depressive symptoms and both alcohol-related variables did not differ by country or sex.

Discussion

This study analysed the relationship between perceived stress and depressive symptoms and alcohol use and the modifying role of religious faith. We used two variables describing distinct patterns of alcohol use. Alcohol-related health and social problems tend to increase as the frequency of alcohol consumption rises [49], hence the first variable that the current study employed is the frequency of drinking, which is a general indicator that does not assess the quantity of alcohol consumed. The second variable is problem drinking, which focuses more on long-term drinking habits and thus represents more serious drinking patterns that have potentially more negative consequences [50, 51]. Such use of two distinct variables produces a more detailed picture of alcohol consumption across countries, and a more holistic understanding of its relationships to mental health indicators and religiosity.

Overall, the study found more high frequency drinking in Western (UK and Germany) and Southern (Bulgaria) European countries than in Central European countries (Slovakia and Poland). Problem drinking was most common in the UK and in Slovakia and least common in Bulgaria and Poland. Our results agree with WHO statistics of per-capita consumption of alcohol in these countries [52].

In relation to perceived stress, several studies of stress and substance use among college student populations provide evidence that stress motivates alcohol consumption [53–56]. Students experiencing higher levels of stress tend to use alcohol and other substances at higher levels and have a higher number of substance-related problems [54, 55]. We confirm this association among university students from five European countries for problem drinking. At the same time, there was no such association for frequency of drinking, which can be explained by the fact that the frequency of drinking is either not an indicator of alcohol problems yet, or that there is a strong influence of local cultures of drinking with regular but not problematic drinking (e.g. regular consumption of wine with meals in Bulgaria as part of a Southern European culture). The association between perceived stress and problem drinking was weaker among students in Germany and Slovakia. It could be that students from these countries have more/other alternative coping mechanisms and thus when encountering stress are less likely to develop problem drinking. Consistent with past studies of college students [3], our findings confirm the positive association between depressive symptoms and problem drinking among university students. Problem drinking can be a consequence of depressive symptoms [21], but the relationship works probably in both ways, so that drinking may lead to depressive symptoms [57].

Problem drinking among college students may be a means of coping with perceived stress and may also vary in relation to coping abilities e.g. religious coping. Results from current study are partly consistent with previous research demonstrating that religious faith was inversely related to the quantity and frequency of alcohol use and problem drinking in samples of college students [28, 34, 58]. In line with a previous study [59] we also found gender differences in religiosity with respect to the high frequency of drinking and with problem drinking. Females with a high level of religiosity were less likely to be involved in high frequency drinking and problem drinking compared to males. This relationship was consistent across countries. Females generally report higher levels of religiosity than males [60, 61], which could be related to different socialization, expected roles, and coping strategies relative to males. Religion may be more important for females and consequently more likely to influence their risk behaviours [62]. On the other side, religiosity did not modify the association between perceived stress or depressive symptoms and alcohol consumption or problem drinking. Given the different religious traditions with majority status in each country, a further interesting finding of the current study is that the effects of religiosity did not differ by country. This supported the notion that religiosity was more important with respect to alcohol consumption than the actual faith/denomination.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. Despite relatively low Cronbach’s alphas off PSS4 for the UK and Slovakia, we decided to keep these countries in the analyses. The alpha coefficient increases with the instrument's length [63]; and it has been argued in previous studies that a reliability coefficient as low as 0.5 should not seriously attenuate validity [64]. Still, the question remains why PSS4 performed worse in the UK and in Slovakia. The results related to prevalence of problem drinking have to be treated with caution as the CAGE test appears not to be an ideal measure of problem drinking in university students [65, 66]. However, the focus of our analysis was not on quantifying problem drinking, but on comparing those with higher and lower scores regarding problem drinking. The relative relationship can remain meaningful even if absolute scores require a different cut-off.

We used a single measure of religiosity. Religiosity is a multi-dimensional construct (i.e. spirituality, beliefs, practices, religious affiliation and attendance) [48], and restricting it only to the dimension of personal importance of faith, which can be viewed as a dimension of spirituality, might have affected the observed relationship between religiosity and use of alcohol [67]. Similarly, given the self-reported measures of drinking, some underreporting, e.g. for problem drinking which is socially undesirable, might have occurred especially among the religious groups of participants. Another limitation is the use of alcohol consumption frequency alone, without consideration of the amount consumed on each occasion. The relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol use may be different for someone who has one drink every day compared with someone who drinks heavily every day.

Regarding the time window of three months for the question on the frequency of alcohol consumption, recall bias also needs to be considered. In addition, each of the applied measures included a different recall period (e.g., past 3 months for frequency of alcohol consumption, lifetime for problem drinking, past few days for depressive symptoms, and past month for perceived stress). This further complicates the already difficult task of interpreting the findings from cross-sectional data in terms of temporality. For example, although problem drinking was regressed on depressive symptoms in the logistic regressions, the experience of alcohol problems may have occurred earlier in a student’s life (e.g. in adolescence) than the recent experience of depressive symptoms. We also did not address the issue of other potential variables associated with alcohol consumption and mental health. For example, it has been suggested in previous studies that when controlling for the effects of anger, depressed mood has little, or no independent effects on alcohol use [68]. Unfortunately, we did not have a measure of emotions such as anger in our questionnaire. Another concern can be the use of just a subjective measure of income sufficiency, instead of an objective amount of income. In one previous publication, we compared the subjective income sufficiency with reported income and concluded that for international comparisons with respect to mental health aspects the latter can be more useful [39].

The sample comprised first-year students. Thus, any generalisations of the findings for all students should be undertaken cautiously. We included only one university per country (except for Slovakia), so the observed differences might be specific site characteristics rather than true differences between countries. Future research should address these limitations.

Conclusions

We confirmed the previously proposed association between perceived stress and depressive symptoms and problem drinking in a culturally different sample of European students from five countries. At the same time, we demonstrated that the association does not exist for the frequency of alcohol consumption. We also showed that religiosity plays a role within this association, but the interaction effect is restricted to females.

These findings should be taken into account when developing prevention programs for problem drinking among students. The policy recommendation for addressing problem drinking should include improvement of mental health and development of coping mechanisms. We studied the effects of religiosity and found out that its role was limited to females, but other coping strategies can be more universal. Many students can ‘feel down’ sometimes. For adolescents and young adults, maladaptive coping mechanisms e.g. drug or alcohol use are common when dealing with social and emotional problems. Such coping strategies are ineffective and provide only immediate relief from stressful situations, and may even exacerbate the problems that the person is currently experiencing. Talking openly, having appropriate social support and adequate coping skills can help prevent the transformation of periods of sadness to more severe depression.

Prevention programs should directly target specific risk factors (e.g. perceived stress, depressive symptoms) that impact on adolescent well-being and focus on implementation programs that teach adaptive coping responses and problem solving skills so that they can effectively handle problems and stressors that typically characterise university students’ lives.

References

Hibell BAB, Bjarnason T, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Kokkevi A, Morgan M: The ESPAD Report, 2003. Alcohol and Other Drug Use Among Students in 35 European Countries. 2004, The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN), Stockholm

White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD: Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: the effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2006, 67: 810-822.

White HR, Labouvie EW, Papadaratsakis V: Changes in substance use during the transition to adulthood: a comparison of college students and their noncollege age peers. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005, 35: 281-305. 10.1177/002204260503500204.

Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS: Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and noncollege youth. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2004, 65: 477-488.

Blanco C: Mental health of college students and their non-college- attending peers: results from the national epidemiologic study on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008, 65: 1429-10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429.

Slutske WS: Alcohol use disorders among us college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005, 62: 321-327. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321.

Johnston-LDOM PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE: Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2004. College Students and Adults Ages 19–45. 2005, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, II

Wechsler H, Kuo M, Lee H, Dowdall GW: Environmental correlates of underage alcohol use and related problems of college students. American Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2000, 19: 24-29. 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00163-X.

Fisher CB, Fried AL, Anushko A: Development and validation of the college drinking influences survey. J Am Coll Health. 2007, 56: 217-230. 10.3200/JACH.56.3.217-230.

Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P: Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995, 69: 990-1005.

McCreary DR, Sadava SW: Stress, drinking, and the adverse consequences of drinking in two samples of young adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998, 12: 247-261.

Newcomb MD, Harlow LL: Life events and substance use among adolescents: mediating effects of perceived loss of control and meaninglessness in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986, 51: 564-577.

Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE: Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 1991, 100: 427-448.

Stewart SH, Devine H: Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000, 29: 495-511. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00210-X.

Windle M: A longitudinal study of stress buffering for adolescent problem behaviors. Dev Psychol. 1992, 28: 522-530.

Cappell H, Greeley J: Alcohol and tension reduction: An update on research and theory. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. Edited by: Blane KEL HT. 1987, Guilford Press, New York, 15-54.

Young RM, Oei TP, Knight RG: The tension reduction hypothesis revisited: An alcohol expectancy perspective. Br J Addict. 1990, 85: 31-40. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb00621.x.

Sher KJ: Stress response dampening. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. Edited by: Blane KEL HT. 1987, Guilford Press, New York, 221-271.

Critchlow B: The powers of John Barleycorn. Beliefs about the effects of alcohol on social behavior. Am Psychol. 1986, 41: 751-764.

Leigh BC: In search of the Seven Dwarves: issues of measurement and meaning in alcohol expectancy research. Psychol Bull. 1989, 105: 361-373.

Jones-Webb R, Jacobs DR, Flack JM, Liu K: Relationships between depressive symptoms, anxiety, alcohol consumption, and blood pressure: results from the CARDIA Study. Coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996, 20: 420-427. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01069.x.

Lindsay V: Factors that predict freshmen college students' preference to drink alcohol. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2006, 50: 7-19.

Brown KW, Ryan RM: The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003, 84: 822-848.

Hawks SR, Hull ML, Thalman RL, Richins PM: Review of spiritual health: definition, role, and intervention strategies in health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1995, 9: 371-378. 10.4278/0890-1171-9.5.371.

Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J: Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: a two-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol. 2004, 9: 713-730. 10.1177/1359105304045366.

Rasic DKS, Langille DB: Protective associations of importance of religion and frequency of service attendance with depression risk, suicidal behaviours and substance use in adolescents in Nova Scotia. Canada. Journal of affective disorders. 2011, 132: 389-395. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.007.

Galen LW, Rogers WM: Religiosity, alcohol expectancies, drinking motives and their interaction in the prediction of drinking among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2004, 65: 469-476.

Patock-Peckham JA, Hutchinson GT, Cheong J, Nagoshi CT: Effect of religion and religiosity on alcohol use in a college student sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998, 49: 81-88. 10.1016/S0376-8716(97)00142-7.

Daugherty TK, McLarty LM: Religious coping, drinking motivation, and sex. Psychological Reports. 2003, 92: 643-647. 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.2.643.

Mikolajczyk RT, Maxwell AE, El Ansari W, Naydenova V, Stock C, Ilieva S, Dudziak U, Nagyova I: Prevalence of depressive symptoms in university students from Germany, Denmark, Poland and Bulgaria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008, 43: 105-112. 10.1007/s00127-007-0282-0.

Stock C, Mikolajczyk R, Bloomfield K, Maxwell AE, Ozcebe H, Petkeviciene J, Naydenova V, Marin-Fernandez B, El-Ansari W, Kramer A: Alcohol consumption and attitudes towards banning alcohol sales on campus among European university students. Public Health. 2009, 123: 122-129. 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.12.009.

Marusic A, Petrovic A, Zorko M: Editorial: Does suicide know the points of the compass?. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008, 54: 387-389. 10.1177/0020764007084255.

Steptoe A, Wardle J: Health behaviour, risk awareness and emotional well-being in students from Eastern Europe and Western Europe. Soc Sci Med. 2001, 53: 1621-1630. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00446-9.

Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Castillo S: Correlates of college student binge drinking. Am J Public Health. 1995, 85: 921-926. 10.2105/AJPH.85.7.921.

Webb E, Ashton CH, Kelly P, Kamali F: Alcohol and drug use in UK university students. Lancet. 1996, 348: 922-925. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03410-1.

Adewuya AO: Prevalence of major depressive disorder in Nigerian college students with alcohol-related problems. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006, 28: 169-173. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.09.002.

Wilks J: Drinking patterns of Australian tertiary youth. Australian Drug and Alcohol Review. 1989, 8: 55-68. 10.1080/09595238980000121.

Akmatov MK, Mikolajczyk RT, Meier S, Krämer A: Alcohol consumption among university students in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany - Results from a multicentre crosssectional study. Journal of American College Health. 2011, 59: 620-626. 10.1080/07448481.2010.520176.

Mikolajczyk RT, Maxwell AE, Naydenova V, Meier S, El-Ansari W: Depressive symptoms and perceived burdens related to being a student. 2008, Clinical Practice and Epidemiolgy in Mental Health, Survey in three European countries, 4-

El Ansari W, Maxwell AE, Mikolajczyk RT, Stock C, Naydenova V, Kramer A: Promoting public health: benefits and challenges of a Europeanwide research consortium on student health. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2007, 15: 58-65.

Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ: A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005, 28: 212-232. 10.1177/0163278705275342.

Tang ST, Dixon J: Instrument translation and evaluation of equivalence and psychometric properties: the Chinese Sense of Coherence Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2002, 10: 59-76. 10.1891/jnum.10.1.59.52544.

Carroll JS HT, Segura-Bartholomew G, Bird MH, Busby DM: Translation and validation of the Spanish version of the RELATE questionnaire using a modified serial approach for cross-cultural translation. Fam Process. 2001, 40: 211-231. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100211.x.

Ewing JA: Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA: The Journal Of The American Medical Association. 1984, 252: 1905-1907. 10.1001/jama.1984.03350140051025.

Cohen S, Fau-Kamarck T, Kamarck T, Fau-Mermelstein R, Mermelstein R: A global measure of perceived stress.

Schmitt M, Beckmann M, Dusi D, Maes J, Schiller A, Schonauer K: Messgüte des vereinfachten Beck-Depressions-Inventars (BDI-V). Diagnostica. 2003, 49: 147-156. 10.1026//0012-1924.49.4.147.

Schmitt M, Maes J: Vorschlag zur Vereinfachung des Beck-Depressions-Inventars (BDI). Diagnostica. 2000, 46: 38-46. 10.1026//0012-1924.46.1.38.

Dein S: Religion, spirituality and depression: Implications for research and treatment. Primary Care and Community Psychiatry. 2006, 11: 67-72. 10.1185/135525706X121110.

Anderson P: Management of alcohol problems: the role of the general practitioner. Alcohol Alcohol. 1993, 28: 263-272.

Engs RC, Diebold BA, Hanson DJ: The drinking patterns and problems of national sample college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1996, 41: 13-33.

Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Maenner G, Gledhill-Hoyt J, Lee H: Changes in binge drinking related to problems among American college students between 1993 & 1997. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Survey. J Am Coll Health. 1998, 47: 57-68. 10.1080/07448489809595621.

WHO: Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004. 2004, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Geneva

Carpenter KM, Hasin DS: Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: a test of three alternative explanations. J Stud Alcohol. 1999, 60: 694-

Colder CR, Chassin L: The stress and negative affect model of adolescent alcohol use and the moderating effects of behavioral undercontrol. J Stud Alcohol. 1993, 54: 326-333.

McCreary DR, Sadava SW: Stress, alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: the influence of negative and positive affect in two cohorts of young adults. J Stud Alcohol. 2000, 61: 466-474.

Rutledge PC, Sher KJ: Heavy drinking from the freshman year into early young adulthood: the roles of stress, tension-reduction drinking motives, gender and personality. J Stud Alcohol. 2001, 62: 457-466.

Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ: Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009, 66: 260-10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543.

Wechsler H, Dowdall G, Davenport A, Rimm E: A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. Am J Public Health. 1995, 85: 982-985. 10.2105/AJPH.85.7.982.

Brown TL, Parks GS, Zimmerman RS, Phillips CM: The role of religion in predicting adolescent alcohol use and problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2001, 62: 696-705.

Francis LJ, Wilcox C: Religion and gender orientation. Personality and Individual Differences. 1996, 20: 119-121. 10.1016/0191-8869(95)00135-S.

Levitt M: Sexual identity and religious socialization. Br J Sociol. 1995, 46: 529-536. 10.2307/591855.

Forthun LF, Bell NJ, Peek CW, Sheh-Wei S: Religiosity, sensation seeking, and alcohol/drug use in denominational and gender contexts. Journal of Drug Issues. 1999, 29: 75-90.

Miller MB: Coefficient alpha: a basic introduction from the perspectives of classical test theory and structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1995, 2: 255-273. 10.1080/10705519509540013.

Schmitt N: Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychol Assess. 1996, 8: 350-

Clements R: A critical evaluation of several alcohol screening instruments using the CIDI-SAM as a criterion measure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998, 22: 985-993. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03693.x.

Maisto SA, Connors GJ, Allen JP: Contrasting self-report screens for alcohol problems: a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995, 19: 1510-1516. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01015.x.

D'Onofrio BM, Murrelle L, Eaves LJ, McCullough ME, Landis JL, Maes HH: Adolescent religiousness and its influence on substance use: preliminary findings from the mid-atlantic school age twin study. Twin Research: The Official Journal Of The International Society For Twin Studies. 1999, 2: 156-168.

Pardini D, Lochman J, Wells K: Negative emotions and alcohol use initiation in high-risk boys: the moderating effect of good inhibitory control. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2004, 32: 505-518.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted through the Cross National Students Health Study group. In addition to the authors, this group includes: Alexander Krämer (Bielefeld, Germany); Nazmi Bilir, Hilal Ozcebe, Dilek Aslan (Ankara, Turkey); Janina Petkeviciene, Jurate Klumbiene, Irena Miseviciene (Kaunas, Lithuania); Francisco Guillen Grima (Pamplona, Spain); Snezhana Ilieva (Sofia, Bulgaria); Urszula Dudziak (Lublin, Poland), and others.This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the contract No. APVV-20-038205 and The Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences under Contract No. VEGA 1/4518/07.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

RS developed the research question, performed the statistical analyses and interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. WEA wrote considerable parts of the manuscript and together with CS and OO commented extensively on the manuscript. RTM developed the study design, supervised the analysis, contributed to the interpretation and writing. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sebena, R., El Ansari, W., Stock, C. et al. Are perceived stress, depressive symptoms and religiosity associated with alcohol consumption? A survey of freshmen university students across five European countries. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 7, 21 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-21