Abstract

Background

Adolescent health is a growing concern. High rates of binge drinking and teenage pregnancies, documented in the UK, are two measures defining poor wellbeing. Improving wellbeing through schools is a priority but information on the impact of wellbeing on alcohol use, and on sexual activity among schoolchildren is limited.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey using self-completed questionnaires was conducted among 3,641 schoolchildren aged 11-14 years due to participate in a sex and relationships education pilot programme in 15 high schools in North West England. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between wellbeing and alcohol use, and wellbeing and sexual activity.

Results

A third of 11 year olds, rising to two-thirds of 14 year olds, had drunk alcohol. Children with positive school wellbeing had lower odds of ever drinking alcohol, drinking often, engaging in any sexual activity, and of having sex. General wellbeing had a smaller effect. The strength of the association between alcohol use and the prevalence of sexual activity in 13-14 year olds, increased incrementally with the higher frequency of alcohol use. Children drinking once a week or more had 12-fold higher odds of any sexual activity, and 10-fold higher odds of having sex. Rare and occasional drinkers had a significantly higher odds compared with non-drinkers.

Conclusions

The relationship between wellbeing and alcohol use, and wellbeing and sexual activity reinforces the importance of initiatives that enhance positive wellbeing in schoolchildren. The association between alcohol use and sexual activity highlights the need for integrated public health programmes. Policies restricting alcohol use may help reduce sexual exposure among young teenagers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The health of adolescents is a growing concern in many countries, particularly in the UK,[1] where children have been identified as having one of the lowest wellbeing scores amongst wealthy nations[2, 3]. Comparison between countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development revealed the lower than average overall child wellbeing score reflected measures on risky behaviours (binge drinking and teen pregnancies), and higher rates of 15-19 year olds not in education, training or employment[4]. As such, the rising prevalence of adolescent alcohol misuse and stubbornly high teenage pregnancy rates are recognised to be national public health priorities[5–8]. Early alcohol use increases the risk of dependency and fuels the growing burden of alcohol-related disease[5]. The teenage birth rate has been found to most closely relate to the overall index of wellbeing[3].

An array of government programmes have been developed to enhance the health and wellbeing of children and young people in the UK, culminating with the Healthy Child Programme (HCP) launched by the Department of Health and Department for Children, Schools and Families[8]. Through the HCP, schools are charged with the duty to promote the wellbeing of their children, provide healthy food, and deliver comprehensive personal, social and health (PSHE) education, including sex and relationships education (SRE). Monitoring of success, through Ofsted,[9] will focus on the five 'Every Child Matters' outcomes: be healthy, stay safe, enjoy and achieve, make a positive contribution, and achieve economic wellbeing[10]. Schools are encouraged to develop their monitoring criteria based on local 'vital signs'; while a number of indicators are recommended for alcohol, no information is available on young people's sexual activities. Evidence demonstrating the relationship between wellbeing indicators and risky health behaviour is limited, particularly among young teenagers, who seldom participate in sexual health research. Research suggests dislike of school is an important determinant of teen pregnancy,[11, 12] and poor school engagement is associated with binge drinking[13]. An association between wellbeing and alcohol use, and wellbeing and sexual activity is therefore likely with important connotations for health policy.

We present findings from a baseline study piloting a sex and relationships (SRE) package for Year 7 to 9 (11-14 year old) children in high schools in North West England, a region documented to have high rates of teenage binge drinking,[14] and above average teenage pregnancy rates[15]. The questioning of children pre-intervention provided a unique opportunity to generate measures on their general and school wellbeing, in association with their reported use of alcohol and their sexual activities.

Methods

Of 17 schools recruited by Government Office North West (GONW) to participate in the teacher training and dissemination of the pilot SRE package, 15 contributed to the pre-intervention baseline cross-sectional survey in the target population. All children in Years 7 to 9 (aged 11 to 14 years), in 66 classes selected by the school leads to participate in the pilot SRE programme, were eligible in the sampling frame. Children outside the year group, severely incapacitated, did not speak English, had a signed withdrawal from consent by a parent or carer, or who personally did not assent, were excluded from the survey.

A baseline cross-sectional survey was organized by staff given lead responsibility for the pilot SRE programme at each local authority in the autumn term of 2008. Letters of invitation were sent to children's homes, to inform parents and enable them to opt-out prior to the survey. Self-completion of the closed questionnaires took place during a PSHE lesson after teachers discussed the project with children and witnessed written assent. The questionnaire asked children about their attitudes towards school life, general wellbeing, and activities outside school including their use of alcohol. Year 9 were also asked about their sexual behaviour. Children were advised they did not have to answer questions and they could stop answering at any time. Teachers or school nurses were available to talk or signpost children if needed.

The study and tools were submitted to and approved by the Ethics Committee of Liverpool John Moores University and the study was endorsed by the Regional Safeguarding Office. Data were stored in an anonymised form.

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows (Release v17.0). Wellbeing questions were abstracted from the national Canadian Youth, Sexual Health, and HIV/AIDS Study [16]. Five items were incorporated on school wellbeing and eight items were incorporated on general wellbeing, three of which were ambiguous and excluded from analyses (see Table 1). Wellbeing items were collapsed from the original 5-point Likert scale into 3-points (agree/don't know/disagree). Other characteristics were binary (yes/no). Alcohol endpoints comprised 'ever drunk' (a full drink not just a sip) and whether those who had ever consumed alcohol were drinking seldom (<once/week) or often (≥once a week). Frequency of alcohol consumption was also included as an independent variable in multivariate analyses of sexual activity and sex, grouped into never, rare (<once/month), occasional (≥once month or more), and frequent (≥once a week). Sexual activity comprised kissing, deep kissing, sexual petting, oral sex, or sexual intercourse. Definitions for each were incorporated into the question. Sex represented a 'yes' response to having had oral sex or intercourse. Bi- and multivariate associations between wellbeing exposure indicators and endpoints (alcohol use, drink often, sexual activity and sex) are reported with unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals. We included one set of wellbeing exposure indicators in the multivariate regression model. The school wellbeing indicator (school is a nice place to be) was chosen because of prior reference to its potential association with teenage pregnancy[11]. The general wellbeing indicator (you have a happy home life) was selected because of its use in school monitoring[9]. Clustering of responses by school was accounted for using the Complex Samples module in SPSS (Release v17.0). This uses Taylor series linearization methods to estimate variances that are in turn used to develop correct standard errors and confidence intervals for statistics of interest. Age and gender were controlled for in the regression models. Differences between groups were determined using Pearson's χ2 test, and significance assigned at the 5% level.

Results

The 15 schools successfully enrolled 3,641 children from 66 classes into the cross-sectional survey at baseline. Parental withdrawal forms were received for 30 children, a further 65 children refused assent, and 255 questionnaires returned were unused/spoilt, generating a non-response rate of 10%. Respondents were equally split by gender (51.6% female). More Year 7 classes were enrolled into the SRE pilot programme, generating a higher proportion of responses (1430, 39.3%) compared with Year 8 (1204; 33.1%) and Year 9 (1007; 27.7%).

Associations between wellbeing and reported alcohol use

Overall, 45.5% of children reported ever drinking alcohol. Prevalence increased from 32.0% in 11 year olds to 65.8% in 14 year olds (Pearsons χ2 = 190.32, df3, p < 0.001). Significantly more 11 year old boys than girls had drunk alcohol (39% versus 25% (Pearsons χ2 = 9.58, df1, p < 0.001), leveling out by age 14 (66.9% in girls versus 63.5% in boys). The mean age of reported first drink for 11 year old boys and girls was 9.4 (standard deviation SD 2.3) and 10.0 (SD 1.9), respectively (p < 0.001). Among drinkers, there was a significant trend for increased frequency of drinking by age (Pearsons χ2 = 11.711, df3, p = 0.008; Linear by linear association χ2 = 6.411, df1, p = 0.011).

In bivariate analyses, the odds of ever drinking alcohol were two-fold higher in children responding negatively to school wellbeing indicators (Table 1). Indicators depicting children's relationship with teachers were more strongly associated. Among general wellbeing indicators, children disagreeing they had a happy home life, or disagreed they were able to talk to parents about problems had the highest odds of ever drinking. Similar associations were recorded between drinking often (versus seldom, among drinkers) and wellbeing (Table 1). In multivariate analysis age, but not gender, was strongly significant for ever drinking, and weakly associated with drinking often (Table 2). A negative response to the selected school wellbeing statements (school is a nice place to be) was associated with a 53% higher odds for ever drinking (Table 2). A negative response to general wellbeing (have a happy home life) was associated with 78% higher odds of drinking often (Table 2).

Associations between wellbeing and sexual activity (Year 9)

Of 768 children in Year 9 (mean age 13.25 years), an equal proportion of boys (49.4%) and girls (55.2%) reported having had some type of sexual activity (Pearsons χ2 = 2.521, df1, p = 0.112). Over half reported kissing, with slightly fewer reporting deep kissing, and a quarter had petted. Oral sex was reported by 11% (boys 13.9%, girls 8.7%; Pearsons χ2 = 5.148, df1, p = 0.023) and intercourse by 10.2% (boys 13.0%, girls 8.0%; Pearsons χ2 = 5.083, df1, p = 0.024).

In bivariate analyses, having any sexual activity, and having sex, was significantly associated with negative responses to school wellbeing indicators (Additional file 1, Table S1). However, negative responses to general wellbeing indicators were mostly not statistically associated. In multivariate analyses, a negative response to school wellbeing (school is a nice place to be) was associated with a two and a half-fold higher odds of having any sexual activity (Table 2). An increased odds of having sex if male was non-significant. The odds of having sex was higher among children responding negatively to school and general wellbeing indicators, however, these did not reach statistical significance.

Associations between alcohol and sexual activity (Year 9)

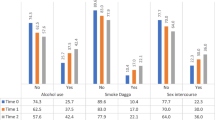

The prevalence of reported sexual activity was associated with their reported frequency of drinking alcohol (Figure 1). The prevalence of sexual activity rose significantly in students who drank more frequently (Pearsons χ2 = 142.31, df3, p < 0.001; Linear-by-Linear Association χ2 = 133.41, df1, p < 0.001). A similar highly significant trend was found for the prevalence of sex in students who drank more frequently (Pearsons χ2 = 69.48, df3, p < 0.001; Linear-by-Linear Association χ2 = 63.68, df1, p < 0.001).

The prevalence of a) any sexual activity and b) sexual intercourse by reported frequency of alcohol use (n = 708). Alcohol frequency: never, very occasionally (rare) (<once/month), occasionally (≥once/month or more), frequently (≥once/week); (a) Any sexual activity includes kissing, deep kissing, petting, oral sex, sexual intercourse; Statistics for any sexual activity: Pearsons χ2 = 142.31, df3, p < 0.001; Linear-by-Linear Association χ2 = 133.41, df1, p < 0.001 (b) Sexual intercourse is limited to those reporting having oral sex and/or intercourse; Statistics for sexual intercourse: Pearsons χ2 = 69.48, df3, p < 0.001; Linear-by-Linear Association χ2 = 63.68, df1, p < 0.001.

In multivariate analysis, the odds of having any sexual activity, and of having sex was incrementally associated with alcohol use, with the odds rising as the frequency of drinking increased (Table 2). This increased from a four-fold higher odds of having any sexual activity in rare compared with non-drinkers, to six-fold higher odds in occasional drinkers, while those drinking weekly or more had a twelve-fold higher odds of any sexual activity compared with non-drinkers (Table 2). Similar rising odds were evident between drinking frequency and having sex. Rare drinkers had two-fold higher odds, occasional drinkers had four-fold higher odds, and frequent drinkers had ten-fold higher odds of having sex (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that negative subjective wellbeing is associated with increased odds of drinking alcohol and engagement with sexual activity. While cause and effect cannot be extrapolated from cross-sectional surveys, the association between wellbeing and risk behaviours was incremental suggesting–as a minimum–that children with poor wellbeing are more likely to also encounter behavioural health risks. Generation of internationally recognised key indicators of poor child wellbeing, such as income and poverty,[3] was precluded from this school-based study since children could not accurately record these data. Nevertheless, youth resilience, self-esteem, social- and school-connectedness are critical determinants of successful transition from childhood into adulthood,[17–19] and the general and school wellbeing indicators we chose represent these themes[16]. Data were generated from the baseline of a sex and relationship education project. Schools were chosen by the Government Office North West, rather than random selection from a broader schools list. The sample was not intended to be representative but opportunistic for both students and classroom participation. Survey participants may thus not be fully representative of all children in North West England. However, schools would have included those agreeing to participate in the SRE pilot, characterizing 'progressive' teaching attitudes, as well as others representing schools in need of educational change. While children across the wellbeing spectrum were represented in our study, and analyses achieved statistical significance, generalising results directly to wider populations should be undertaken with caution. Our main analyses thus focuses on relationships between variables recorded by individual participants and do not seek to establish population prevalence. Despite these caveats we believe this study contributes further evidence to the hypothesis that school wellbeing influences children's risk behaviours,[11, 12, 20] and supports current efforts to enhance wellbeing at school[8].

Dislike of school has been identified as a potential contributor to teenage pregnancy risk,[11, 12] and to substance abuse, poor mental health, and low academic achievements[13, 17, 19]. Strengthening school-connectedness and development of resiliency programmes has thus been recommended to reduce teen pregnancies and substance misuse in the UK[13, 20]. However, a UK-based multi-component youth development programme did not secure a reduction in teen pregnancy, substance abuse and other harms, suggesting further understanding is needed to clarify factors that are associated with risky behaviours in teenagers[21]. Our study found children stating a dislike of school had 2.5-fold higher odds of having any sexual relationship and 86% higher odds of having sex, although the latter was not statistically significant. Dislike of school also strongly predicted alcohol use. We also explored other school wellbeing indicators, noting teacher-related markers were more strongly associated with alcohol use and frequency of drinking. Clearly, children involved with risky health behaviours are most in need of guidance and support through school programmes, but they appear to be the very children who poorly engage and are thus less receptive to learning new skills. Programmes supporting targeted activities to bring about healthier behaviours, such as the Healthy Schools enhancement model,[8] thus need to pay particular attention to fostering the engagement of disenfranchised children.

We report evidence of an incremental association between the frequency of alcohol use and the prevalence of sexual activity, including having sex, among young teenagers. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show such a strong and consistent association between alcohol use and sexual activity in children the UK, although the contributions of alcohol to pregnancy has been explored[22]. In the largest UK-based study of sexual activity in teenagers, being drunk or stoned elevated the risk of regretted sex, but student self-recording of being drunk was not found to be a strong predictor of sexual activity[23]. However, a survey among 15-16 year olds in north west England in 2007 found an association between binge drinking and sexual regret, but data on children's sexual activity were not available to explore this association further[14]. International studies have noted associations between alcohol and early onset of sexual activity,[24, 25] having multiple sexual partners,[26, 27] and becoming pregnant[28]. An American study of young people aged 12 to 20 years, showed a correlation between pregnancy and rates of binge drinking[29]. They documented a 30-fold higher odds of making/becoming pregnant in persons bingeing up to 10 times in the past 30 days, 10-fold in those bingeing twice, and 4-fold in non-bingers, compared with non-drinkers. In our study we also noted that the odds of having sexual activity (and sex) were higher among children who reported drinking rarely, compared with non-drinkers. This corroborates studies showing that even low level drinking increases the potential risk of harm[14, 29].

Conclusions

This study adds UK data to an international body of knowledge showing an association between alcohol and sexual activity, and confirms this occurrence in children, including young teenagers exploring early sexual activity prior to sexual debut. Such findings, along with evidence showing early onset of alcohol use, highlight the need to start educational activities early in schoolchildren's lives and calls into question the wisdom of abandoning statutory sex and relationships education. The relationship between risk behaviours underscores the need to integrate public health strategies and policies, to maximise opportunities to combat harms associated with alcohol abuse and poor sexual health. It also supports calls to strengthen policies to reduce the access and availability of alcohol to young teenagers[5, 6, 14]. The association between risk behaviours and wellbeing reinforces the importance of wellbeing and life skills programmes developed for school-aged children. Information generated from our survey provides early insights on the potential role of wellbeing in modulating risk behaviours that need to be tested more widely if we are to understand and develop meaningful strategies to protect children and young people from harm.

References

Viner R, Booy R: ABC of adolescence: Epidemiology of health and illness. BMJ. 2005, 411-414. 10.1136/bmj.330.7488.411.

UNICEF: Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Wellbeing in Rich Countries. United Nations Children Fund Innocenti Report Card No7, Innocenti Research Centre. Florence, Italy. 2007

Pickett K, Wilkinson R: Child wellbeing and income inequality in rich societies: ecological cross sectional study. BMJ. 2007, 10: 1136-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Chapter 2: Comparative child well-being across the OECD doing better for children. 2009, 60:

British Medical Association: Alcohol misuse: tackling the UK epidemic. BMA Board of Science. London. 2008

Donaldson L: Guidance on the consumption of alcohol by children and young people. 2009, London: Department of Health

Department for Education and Skills: Teenage Pregnancy: Accelerating the Strategy to 2010. 2006

Department for Children Schools and Families: Healthy Child Programme: From 5-19 years old. 2009, London Central Office of Information

Department for Children Schools and Families: Ofsted Indicators of a school's contribution to wellbeing. London. 2008

Every Child Matters.http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters/

Bonell C, Allen E, Strange V, Copas A, Oakley A, Stephenson A: The effect of dislike of school on risk of teenage pregnancy: testing of hypotheses using longitudinal data from a randomised trial of sex education. J Epid Comm Health. 2005, 223-230. 10.1136/jech.2004.023374.

Harden A, Bruton G, Fletcher A, Oakley A: Teenage pregnancy and social disadvantage: systematic review integrating controlled trials and qualitative studies. BMJ. 2009, 339: 10.1136/bmj.b4254.

Viner RM, Taylor B: Adult outcomes of binge drinking in adolescence: findings from a UK national birth cohort. J Epid Comm Health. 2007, 902-907.

Bellis M, Phillips-Howard P, Hughes K, Hughes S, Cook P, Morleo M, Hannon K, Smallthwaite L, Jones L: Teenage drinking, alcohol availability and pricing: a cross-sectional study of risk and protective factors for alcohol-related harms in school children. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9: 380-10.1186/1471-2458-9-380.

Office for National Statistics: Conceptions to women aged under 18 - annual numbers and rates 2001-2008. 2010http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/ssdataset.asp?vlnk=8903&More=Y

Boyce W, Doherty M, Fortin C, MacKinnon D: Canadian Youth, Sexual Health, and HIV/AIDS Study Factors influencing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours. Council of Ministers of Education. Canada. 2003

Bond L, Butler H, Thomas L, Carlin J, Glover S, Bowes G: Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2007, 40: 9-18. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013.

Hopkins G, McBride D, Marshak H, Freier K, Stevens J, Kannenberg W, Weaver J, Sargent Weaver S, Landless P, Duffy J: Developing healthy kids in healthy communities: eight evidence-based strategies for preventing high-risk behaviour. Med J Australia. 2007, 184 (Suppl): 70-73.

Resnick M, Bearman P, Blum R: Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997, 823-832. 10.1001/jama.278.10.823.

Bonell C, Fletcher A, McCambridge J: Improving school ethos may reduce substance misuse and teenage pregnancy. BMJ. 2007, 614-616. 10.1136/bmj.39139.414005.AD.

Wiggins M, Bonell C, Sawtell M, Austerberry H, Burchett H, Allen E, Strange V: Health outcomes of youth development programme in England: prospective matched comparison study. BMJ. 2009, 2534-10.1136/bmj.b2534.

Bellis MA, Morleo M, Tocque K, Dedman D, Phillips-Howard PA, Perkins C, Jones L: Contributions of alcohol use to teenage pregnancy: An initial examination of geographical and evidence based associations. 2009, North West Public Health Observatory, Centre for Public Health, Liverpool John Moores University

Wight D, Parkes A, Strange V, Allen E, Bonell C, Henderson M: The Quality of Young People's Heterosexual Relationships: a longitudinal analysis of characteristics shaping subjective experience. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008, 40: 226-237. 10.1363/4022608.

Fergusson D, Lynskey M: Alcohol misuse and adolescent sexual behaviours and risk taking. Pediatrics. 1996, 98: 91-96.

Choquet M, Manfriedi R: Sexual intercourse, contraception, and risk taking behaviour among unselected French adolescents aged 11-20 years. J Adolesc Health. 1992, 623-630. 10.1016/1054-139X(92)90378-O.

Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Goebert D, Nishimura S: Ethnic variation in drinking, drug use, and sexual behaviour among adolescents in Hawaii. J School Health. 2004, 74: 16-22. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06596.x.

Cook R, Pollock N, Rao A, Clark D: Increased prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among adolescent women with alcohol use disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2002, 169-174. 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00339-1.

Wells J, Horwood L, Fergusson D: Drinking patterns in mid-adolescence and psychosocial outcomes in late adolescence and early adulthood. Addiction. 2004, 1529-1541. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00918.x.

Miller J, Naimi T, Brewer R, Everett Jones S: Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviours among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007, 119 (1): 76-85. 10.1542/peds.2006-1517.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the PSHE pilot leads, teachers, and children who we thank for their valuable contribution towards this study. Government Office North West (GONW), and Cheshire and Merseyside Sexual Health Network provided funding for this project. We are grateful to Mark Limmer, GONW, and to Simon Henning, Cheshire and Merseyside Sexual Health Network, for their support. GONW guided the PSHE pilot leads on the implementation of the SRE pilot, commented on the questionnaires and project design. We are most grateful to Feiko ter Kuile for his statistical advice. The researchers confirm their independence from funders and sponsors. All researchers had access to all the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PAPH conceptualised, oversaw and wrote the study for this manuscript. PAPH, MAB and LBB analysed the data. HJ, IEK, TB and PAC contributed to data preparation, analysis and manuscript production. PAC, MAB, and JD designed the SRE evaluation project and edited the manuscript. HJ and JD managed the SRE evaluation project. MAB appraised the study for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13011_2010_146_MOESM1_ESM.DOC

Additional file 1: Table S1: Bivariate associations between wellbeing and sexual activity among schoolchildren aged 13 to 14 years. (DOC 84 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips-Howard, P.A., Bellis, M.A., Briant, L.B. et al. Wellbeing, alcohol use and sexual activity in young teenagers: findings from a cross-sectional survey in school children in North West England. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 5, 27 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-5-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-5-27