Abstract

Background

In the last 20 years, Cetacean Morbillivirus (CeMV) has been responsible for many die-offs in marine mammals worldwide, as clearly exemplified by the two dolphin morbillivirus (DMV) epizootics of 1990–1992 and 2006–2008, which affected Mediterranean striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba). Between March and April 2011, the number of strandings on the Valencian Community coast (E Spain) increased.

Case presentation

Necropsy and sample collection were performed in all stranded animals, with good state of conservation. Subsequently, histopathology, immunohistochemistry, conventional reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and Universal Probe Library (UPL) RT-PCR assays were performed to identify Morbillivirus. Gross and microscopic findings compatible with CeMV were found in the majority of analyzed animals. Immunopositivity in the brain and UPL RT-PCR positivity in seven of the nine analyzed animals in at least two tissues confirmed CeMV systemic infection. Phylogenetic analysis, based on sequencing part of the phosphoprotein gene, showed that this isolate is a closely related dolphin morbillivirus (DMV) to that responsible for the 2006–2008 epizootics.

Conclusion

The combination of gross and histopathologic findings compatible with DMV with immunopositivity and molecular detection of DMV suggests that this DMV strain could cause this die-off event.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Over the last 20 years, epizootics caused by Cetacean morbillivirus (CeMV) (genus Morbillivirus, family Paramyxoviridae) have occurred among cetacean populations worldwide and have caused mass mortality [1]. Three main CeMV groups have been described: dolphin morbillivirus (DMV) [2], porpoise morbillivirus (PMV) [3] and pilot whale morbillivirus (PWMV) [4, 5].

The spread of DMV infection in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) in the Mediterranean Sea caused around 1000 deaths in 1990–1992 [6]. This outbreak started in 1990 in the Gulf of Valencia, in the Spanish Mediterranean Sea [7], and propagated along European Mediterranean coasts over the following months [2, 8]. Then in 2007, a new DMV outbreak occurred off the Spanish Mediterranean coast. It affected approximately 100 striped dolphins [9] and up to 60 long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas) [10], and subsequently spread to the French Mediterranean coast [11].

In the last two decades, the annual mean mortality rate of dolphins stranded off the Mediterranean coast of Valencia has been 28.4 animals per year. However this rate lowers to 18.3 animals per year if the 1990 and 2007 outbreak years are excluded [12].

In the present study, 37 dolphins are reported as stranded dolphins in 2 months, which represents more than the annual mean in that region. An evaluation of Morbillivirus infection revealed the overwhelming positivity of the stranded animals, suggesting that DMV could be responsible for this increase in strandings, which might be the third DMV epizootic in the Mediterranean Sea.

Case presentation

Thirty-seven dolphins stranded along the Valencian Mediterranean coast between March and April 2011: 26 striped dolphins (S. coeruleoalba), three bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and eight dolphins of undetermined species (poor level of conservation hampered species identification).

Necropsies were performed according to standard protocols of the European Cetacean Society [13]. Stranded dolphins were recovered from the Valencia Mediterranean coast of Spain (39°N, 0°W) by the Marine Mammal Stranding Network of the Conselleria de Infraestructuras, Territorio y Medio Ambiente of Valencia. A detailed post-mortem examination could be carried out on 11 animals (nine striped dolphins and two bottlenose dolphins) since other animals were poorly preserved.

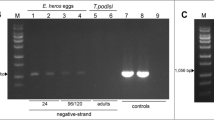

Fresh tissue samples (brain, lung, kidney, liver, lymph node, tonsil, thymus, spleen and skin) were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histopathology, refrigerated for microbiology, and tissue samples were frozen for molecular diagnosis. Immunohistochemical staining with a Canine Distemper Virus monoclonal antibody specific for nucleoprotein, IgG2B isotype (CDV-NP. VMRD®, Inc.), was carried out on selected samples of brain, lung, kidney, urinary bladder, stomach and intestine. Frozen tissues were homogenized using a Bullet BlenderTM (Next Advance, Inc., Averill Park, NY), and total nucleic acid was extracted using the NucleoSpin RNA II Kit (Macherey-Nagel) for RNA extraction and the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit for DNA extraction, following the manufacturers’ instructions in both kits. For the molecular CeMV diagnosis, real-time RT-PCR assays, based on the Universal Probe Library (UPL) platform, that target, a sequence within the fusion protein gene, was carried out [14].

CeMV infection was confirmed by sequencing the real-time RT-PCR products. For the phylogenetic analysis, in addition to the fusion protein gene, the DMV phosphoprotein (P) and nucleoprotein (N1 and N2) genes were amplified by conventional RT-PCRs assays according to published protocols [4, 15] in some positive sample. A BLAST analysis was used to compare the obtained phosphoprotein and nucleoprotein sequences with all the CeMV sequences available in GenBank. A phylogenetic analysis was performed using the MEGA 4.0 software [16]. P-distance matrices were calculated, and tree topology was inferred by the neighbor-joining maximum composite likelihood method to test the reliability of the topology by bootstrapping 1000 replicates generated with a random seed.

Brucella spp. and Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) diagnoses were carried out in the animals whose non suppurative encephalitis was observed in the histopathological analysis. The molecular identification of Brucella spp. was performed in the brains of suspected animals by TaqMan Real time PCR, targeting the insertion sequence IS711 of Brucella spp. [17]. Additionally, T. gondii DNA was detected by nested PCR, in which the target formed part of the sequence of repetitive gene B1 (194 bp, 97 bp) using the method described by Montoya et al. [18].

Thirty-seven dolphins were stranded on the Mediterranean coast of Valencia (Spain) in mid-2011. The epizootic started at the beginning of March 2011 with a low stranding rate, but gradually increased during this month (Figure 1).

Comparison of cumulative percentages of dolphins stranded in 1990, 2007 and 2011 epizootics. The 2011 curve represents % between March and April 2011. 1990 and 2007 curves shows % between July and August 1990 and 2007. In 2011 curve, day 0 corresponds to 12th of March 2011. Data from 1190 and 2007 are extracted from Raga et al. 2008.

A widespread poor body condition was observed in the necropsies. Mainly gross findings were localized in the central nervous, respiratory, lymphoid and digestive systems (Table 1).

The histopathological analysis showed severe non suppurative meningoencephalitis with numerous intranuclear inclusion bodies in three individuals (Figure 2B). Perivascular cuffing with many layers of mononuclear cells were found to especially affect inflammatory meningeal areas, vessels of cortical gray matter and, to a lesser extent, in the white matter areas. Positive immunostaining revealed the Morbillivirus antigen in glial cells and astrocytes of the brain in one of the three individuals (Figure 2B). Focal bronchointerstitial pneumonia with few giant cells was observed in some animals. However in lymphnodes, the necrotic areas in reticular and perivascular cells were found. No immunopositivity was revealed in either the lungs or lymph nodes from any animal.

Brain dolphin with morbillivirus infection. (A) Severe non-suppurative encephalitis with acidophilic intranuclear viral inclusions (arrows) (H&E) Original amplification ×20. (B) Positive immunoperoxidase staining of morbilliviral antigen in glial cells and astrocytes of the brain (arrows). Avidin-biotin-peroxidase with Harris hematoxylin counterstain. Original magnification × 40.

According to the molecular diagnosis performed by UPL RT-PCR assays, seven of the eleven analyzed dolphins were positive in DMV/PMV UPL PCR, which represents 63.6% of positivity to CeMV. They were all striped dolphins. After considering that the most affected specie in the last Mediterranean DMV epizootics was striped dolphin, the percentage was calculated in relation to all the analyzed striped dolphins, which changed to 78% of positivity (seven positive striped dolphins as compared to nine analyzed striped dolphins) (Table 1). Furthermore, the systemic form of the disease was found in five of these seven animals, which contained at least two positive tissues. However, only one of the seven positive animals analyzed by UPL RT-PCR was positive for phosphoprotein by conventional PCR, and this positivity was restricted to brain.

Sequencing the amplicons from the fusion protein gene (F) [14], the phosphoprotein gene (P) [15] and the two fragments of the nucleoprotein gene, named N1 [5] and N2 [19], confirmed infection by DMV. The phosphoprotein gene sequence obtained from the brain of one striped dolphin (GenBank accession number JN210891) showed a p-distance of 0.003 with the 2007 Spanish strain (GenBank EU039963) [10] and of 0.015 with the 1990 Spanish strain (GenBank AJ608288). Thus, the phosphoprotein gene sequences for the 2007 and 2011 Spanish strains were 98.5% identical (Figure 3). In addition, the fusion protein sequences showed 100% identity with the 1990 Spanish strain (GenBank AJ608288) and the 2007 Spanish strain (GenBank accession number HQ829972) [20] (Figure 3). Complementarily, the N2 fragment of 495 bp [19] and the N1 fragment of 181 bp of the nucleoprotein gene [5] were compared with other DMV nucleoprotein gene sequences, which confirmed that the 2011 DMV strain evolved from the 1990 DMV strain and the 2007 DMV strain (Figure 3). The N1 sequence was 100% identical to the others observed in the Mediterranean Sea from 2007 to 2012 [20, 21], whereas the N2 fragment showed a similarity of 99.8% with the DMV sequence obtained from the Globicephala melas mass stranding of 2007 [20].

Neighbor-joining phylogram of morbillivirus phosphoprotein (P), fusion (F) and nucleoprotein (N1 and N2) genes sequences. The name of each sequence is composed of the virus name (DMV, dolphin morbillivirus; CeMV, Cetacean morbillivirus; PMV, porpoise morbillivirus; PWMV, pilot whale morbillivirus; PPRV, Peste-des-Petits-Ruminants virus; RPV; Rinderpest virus; CDV, Canine Distemper virus; PDV, Phocine Distemper virus; MeV, Measles virus), GenBank accession number, cetacean species infected (Sc, Stenella coeruleoalba; Gme, Globicephala melas; La, Lagenorhynchus albirostris; Kb, Kogia breviceps; Tt, Tursiops truncatus; Pp, Phocoena phocoena; Gma, Globicephala macrorhynchus), the year and the geographical area of the stranding (At, Atlantic Ocean; Me, Mediterranean Sea; No, North Sea; Pa, Pacific Ocean).

The microbiological investigations found no pathologically significant microorganisms. As regards Brucella spp. and T. gondii PCRs, negative results were identified in the three animals with non suppurative encephalitis.

The 37 strandings in just 2 months might represent an unusual mortality event if we consider the annual number of stranded dolphins has not been exceeded since 1990, except in 1990 and 2007, on Valencian Mediterranean coasts [12]. DMV was considered the causative agent of this increase in strandings in 1990 and 2007 [7, 9]. In addition, this is not the first description of DMV in the Mediterranean Sea in 2011. In Italy, DMV has been reported in striped dolphins, bottlenose dolphins and fin whales on almost the same dates as this report [21–24]. Accordingly, Morbillivirus infection finding might be related with the rise in strandings in 2011.

DMV detection by the UPL RT-PCR assay in 78% of the analyzed striped dolphins highlights the important role that DMV plays in this unusual episode of mass strandings. At the same time, the recognition of DMV in at least two tissues in five animals may indicate the general spread of this virus, most likely by the circulatory system. Failure to detect CeMV in the central nervous system (CNS) in all the positive animals can be explained by the fact that distribution of CeMV brain infection is not homogeneous [25] and that the CNS samples in this study were not collected uniformly; thus it was impossible to determine from which brain region each sample had been taken. In addition, Toxoplasma gondii and Brucella spp. have been related with encephalitis in stranded dolphins [26, 27], and even together with CeMV [22]. However in our study, any of the three cases with non suppurative encephalitis can be related with these pathogens.

A comparison made of the striped dolphin outbreaks in 1990, 2007, and 2011 suggests a change in DMV epidemiology in the Western Mediterranean Sea. In 2011, mortality was even lower, lesions were less severe, and mostly younger animals were affected. Since enzootic infections in wildlife are characterized by milder lesions and lighter pathogen loads than epizootics [28], it is possible that DMV epidemiology in striped dolphins in the Western Mediterranean is changing from epizootic to enzootic infection, as suggested by others [20, 25]. Systematic serological surveys are urgently required to address this question.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the presence of DMV-compatible lesions, the antigen detection in one of the animals and the molecular detection of DMV genomic sequences all suggest that DMV is associated with this unusual mass mortality episode in striped dolphins in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Further research to define how the virus circulates and causes epidemics in the Mediterranean Sea, and why only striped dolphins were affected in 2011, is warranted.

Abbreviations

- CeMV:

-

Cetacean morbillivirus

- DMV:

-

Dolphin morbillivirus

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- UPL:

-

Universal probe library

- PMV:

-

Porpoise morbillivirus

- PWMV:

-

Pilot whale morbillivirus

- S. coeruleoalba:

-

Stenella coeruleoalba

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system.

References

Van Bressem MF, Raga JA, Di Guardo G, Jepson PD, Duignan PJ, Siebert U, Barrett T, Santos MC, Moreno IB, Siciliano S: Emerging infectious diseases in cetaceans worldwide and the possible role of environmental stressors. Dis Aquat Organ. 2009, 86 (2): 143-157.

Domingo M, Ferrer L, Pumarola M, Marco A, Plana J, Kennedy S, McAliskey M, Rima BK: Morbillivirus in dolphins. Nature. 1990, 348 (6296): 21-

Kennedy S: Morbillivirus infections in aquatic mammals. J Comp Pathol. 1998, 119 (3): 201-225. 10.1016/S0021-9975(98)80045-5.

Bellière EN, Esperón F, Fernandez A, Arbelo M, Munoz MJ, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM: Phylogenetic analysis of a new Cetacean morbillivirus from a short-finned pilot whale stranded in the Canary Islands. Res Vet Sci. 2011, 90 (2): 324-328. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.05.038.

Taubenberger JK, Tsai MM, Atkin TJ, Fanning TG, Krafft AE, Moeller RB, Kodsi SE, Mense MG, Lipscomb TP: Molecular genetic evidence of a novel morbillivirus in a long-finned pilot whale (Globicephalus melas). Emerg Infect Dis. 2000, 6 (1): 42-45. 10.3201/eid0601.000107.

Lipscomb TP, Kennedy S, Moffett D, Krafft A, Klaunberg BA, Lichy JH, Regan GT, Worthy GA, Taubenberger JK: Morbilliviral epizootic in bottlenose dolphins of the Gulf of Mexico. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1996, 8 (3): 283-290. 10.1177/104063879600800302.

Aguilar A, Raga JA: The striped dolphin epizootic in the Mediterranean Sea. Ambio. 1993, 22: 524-528.

Duignan PJ, Geraci JR, Raga JA, Calzada N: Pathology of morbillivirus infection in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) from Valencia and Murcia. Spain. Can J Vet Res. 1992, 56 (3): 242-248.

Raga JA, Banyard A, Domingo M, Corteyn M, Van Bressem MF, Fernandez M, Aznar FJ, Barrett T: Dolphin morbillivirus epizootic resurgence, Mediterranean Sea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008, 14 (3): 471-473. 10.3201/eid1403.071230.

Fernandez A, Esperon F, Herraez P, de Los Monteros AE, Clavel C, Bernabe A, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM, Verborgh P, DeStephanis R, Toledano F: Morbillivirus and pilot whale deaths, Mediterranean Sea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008, 14 (5): 792-794. 10.3201/eid1405.070948.

Keck N, Kwiatek O, Dhermain F, Dupraz F, Boulet H, Danes C, Laprie C, Perrin A, Godenir J, Micout L: Resurgence of Morbillivirus infection in Mediterranean dolphins off the French coast. Vet Rec. 2010, 166 (21): 654-655. 10.1136/vr.b4837.

Gonzalbes P, Jiménez J, Raga JA, Tomás J, Gómez JA, Eymar J: Cetáceos y tortugas marinas en la Comunitat Valenciana 20 años de seguimiento. Edited by: Consellería de Medio Ambiente A. 2010, Valencia, Spain: Urbanismo y Vivienda, 92-

Kuiken T, García-Hartmann M: Dissection techniques and tissue sampling. First ECS workshop on Cetacean Pathology: 1991. 1991, Leiden, Netherlands: European Society Newsletter No. 17-Special issue, 39-

Rubio-Guerri C, Melero M, Rivera-Arroyo B, Bellière EN, Crespo JL, García-Párraga D, Esperón F, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM: Simultaneous diagnosis of Cetacean morbillivirus infection in dolphins stranded in the Spanish Mediterranean sea in 2011 using a novel Universal Probe Library (UPL) RT-PCR assay. Vet Microbiol. 2012, 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.031.

Barrett T, Visser IK, Mamaev L, Goatley L, van Bressem MF, Osterhaust AD: Dolphin and porpoise morbilliviruses are genetically distinct from phocine distemper virus. Virology. 1993, 193 (2): 1010-1012. 10.1006/viro.1993.1217.

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Bio Evol. 2007, 24 (8): 1596-1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092.

Hinic V, Brodard I, Thomann A, Cvetnic Z, Makaya PV, Frey J, Abril C: Novel identification and differentiation of Brucella melitensis, B. abortus, B. suis, B. ovis, B. canis, and B. neotomae suitable for both conventional and real-time PCR systems. J Microbiol Methods. 2008, 75 (2): 375-378. 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.002.

Montoya A, Miro G, Blanco MA, Fuentes I: Comparison of nested PCR and real-time PCR for the detection of Toxoplasma gondii in biological samples from naturally infected cats. Res Vet Sci. 2010, 89 (2): 212-213. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.02.020.

van de Bildt MW, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD: Cetacean morbilliviruses are phylogenetically divergent. Arch Virol. 2005, 150 (3): 577-583. 10.1007/s00705-004-0426-4.

Belliere EN, Esperon F, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM: Genetic comparison among dolphin morbillivirus in the 1990–1992 and 2006–2008 Mediterranean outbreaks. Infect Genet Evol. 2011, 11 (8): 1913-1920. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.08.018.

Mazzariol S, Peletto S, Mondin A, Centelleghe C, Di Guardo G, Di Francesco CE, Casalone C, Acutis PL: Dolphin morbillivirus infection in a captive harbor seal (Phoca vitulina). J Clin Microbiol. 2013, 51 (2): 708-711. 10.1128/JCM.02710-12.

Mazzariol S, Marcer F, Mignone W, Serracca L, Goria M, Marsili L, Di Guardo G, Casalone C: Dolphin Morbillivirus and Toxoplasma gondii coinfection in a Mediterranean fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). BMC Vet Res. 2012, 8: 20-10.1186/1746-6148-8-20.

Di Guardo G: Morbillivirus-host interaction: lessons from aquatic mammals. Front Microbiol. 2012, 3: 431-

Di Guardo G, Di Francesco CE, Eleni C, Cocumelli C, Scholl F, Casalone C, Peletto S, Mignone W, Tittarelli C, Di Nocera F: Morbillivirus infection in cetaceans stranded along the Italian coastline: pathological, immunohistochemical and biomolecular findings. Res Vet Sci. 2013, 94 (1): 132-137. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.07.030.

Domingo M, Vilafranca M, Visa J, Prats N, Trudgett A, Visser I: Evidence for chronic morbillivirus infection in the Mediterranean striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba). Vet Microbiol. 1995, 44 (2–4): 229-239.

Roe WD, Howe L, Baker EJ, Burrows L, Hunter SA: An atypical genotype of Toxoplasma gondii as a cause of mortality in Hector’s dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori). Vet Parasitol. 2013, 192 (1–3): 67-74.

Alba P, Terracciano G, Franco A, Lorenzetti S, Cocumelli C, Fichi G, Eleni C, Zygmunt MS, Cloeckaert A, Battisti A: The presence of Brucella ceti ST26 in a striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) with meningoencephalitis from the Mediterranean Sea. Vet Microbiol. 2013, 164 (1–2): 158-163.

Sinclair ARE, Fryxell JM, Caughley G: Parasites and pathogens. Wildlife ecology, conservation, and management. 2006, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 179-195.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Miró Corrales and Dr. Montoya from Complutense University of Madrid and Dr. Fuentes from Parasitology Service of the National Centre of Microbiology in the Carlos III Institute of Health for the Toxoplasma gondii diagnosis. This work has been supported by a collaborative agreement between the Conselleria de Infraestructuras, Territorio y Medio Ambiente of Valencia of Valencia; the Oceanographic Aquarium of the Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias of Valencia; the VISAVET Center of Complutense University of Madrid; and the Pfizer Foundation. This work was cofinanced by Project CGL2009-08125 of the Spanish National Research Plan. The authors thank the Institut Cavanilles de Biodiversitat i Biologia Evolutiva, University of Valencia, for collaboration on necropsies, and Elena Neves, Belén Rivera, Verónica Nogal and Rocío Sánchez for technical assistance. Mar Melero is the recipient of a PhD student grant from the University Complutense of Madrid and Consuelo Rubio is the recipient of a FPU grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Necropsies were performed by JLC, CRG and MM; microscopic examination and immunhistochemistry were carried out by ES and MA; the viral study and the phylogenetic study were analyzed by CRG, MM, NEB, and FE; the manuscript was prepared and critically discussed by CRG, MM, FE, NEB and JMSV, with contributions by all the remaining authors. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consuelo Rubio-Guerri, Mar Melero contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubio-Guerri, C., Melero, M., Esperón, F. et al. Unusual striped dolphin mass mortality episode related to cetacean morbillivirus in the Spanish Mediterranean sea. BMC Vet Res 9, 106 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-9-106

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-9-106