Abstract

Background

Lesions on sows' limbs and bodies are an abnormality that might impact on their welfare. The prevalence of and risks for limb and body lesions on lactating sows on commercial English pig farms were investigated using direct observation of the sows and their housing.

Results

The prevalence of lesions on the limbs and body were 93% (260/279) and 20% (57/288) respectively. The prevalence of limb and body lesions was significantly lower in outdoor-housed sows compared with indoor-housed sows. Indoor-housed sows had an increased risk of wounds (OR 6.8), calluses (OR 8.8) and capped hock (OR 3.8) on their limbs when housed on fully slatted floors compared with solid concrete floors. In addition, there was an increased risk of bursitis (OR 2.7), capped hock (OR 2.3) and shoulder lesions (OR 4.8) in sows that were unwilling to rise to their feet. There was a decreased risk of shoulder lesions (OR 0.3) and lesions elsewhere on the body (OR 0.2) in sows with more than 20 cm between their tail and the back of the crate compared with sows with less than 10 cm.

Conclusion

The sample of outdoor housed sows in this study had the lowest prevalence of limb and body lesions. In lactating sows housed indoors there was a general trend for an increased risk of limb and body lesions in sows housed on slatted floors compared with those housed on solid concrete floors with bedding. Sows that were less responsive to human presence and sows that had the least space to move within their crates had an additional increased risk of lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Outdoors, sows farrow in a hut with free access to an outdoor paddock. In indoor production, sows usually farrow within a farrowing crate in an individual pen. The crate floor must, as far as possible, meet all the sow's needs for a comfortable surface for lying, sufficient space and a non slip surface for rising and standing, separation from excreta and be robust to her size and weight. To meet these requirements and to minimise labour, farrowing pen floors are often slatted and have little or no bedding.

In farrowing pens the floor type has been associated with the risk of developing limb and body lesions. In 383 lactating sows on an experimental unit the lowest prevalence of limb wounds occurred in sows housed on solid concrete floors and the prevalence increased as the proportion of the pen that was slatted increased [1]. In pregnant sow housing, slatted floors, compared with solid floors, and absence of bedding have been reported to be associated with increased prevalence of bursitis [2] and calluses [3]. Slatted floors were associated with an increased risk of body lesions in 555 lactating sows from 10 commercial herds in Denmark [4]. Further risks for body lesions include small farrowing crates [5], poor body condition [4, 6–9] and wet skin [4, 6, 9].

In this paper, the prevalence of, population attributable fractions for, and risks associated with limb and body lesions in a sample of lactating sows housed indoors and outdoors are presented.

Methods

Sample size

The data presented in this paper were collected as part of a larger study investigating the impact of floor type on commercially reared pigs of all ages. The farm selection criteria were breeder-to-finisher units with more than 100 breeding sows. In the absence of published studies on the prevalence of limb and body lesions in lactating sows in Britain, estimates from rearing pigs, were used [10]. Assuming 95% of herds have sows with limb and body lesions and an approximate population of 1,870 (number of herds fitting the selection criteria in 2003 in Britain according to DEFRA, personal communication) with 95% confidence intervals and 5% precision, it was calculated that it was necessary to sample sows from a minimum of 75 farms. A figure of 100 farms was chosen for the study design.

Assuming an approximate study population of 60,000 lactating sows on the target population farms (average herd size 220 sows according to DEFRA, 2003 data, personal communication), 50% lesion prevalence, a 95% confidence interval and 5% precision, with a farm level intraclass coefficient of 0.1 [11], it was calculated that a sample of approximately 400 lactating sows was required to estimate the prevalence of lesions if four sows were sampled from each of 100 farms. To detect a 3 fold difference in risk between exposed and unexposed sows with 95% confidence and 80% power given a 10% prevalence of disease in the unexposed sows, with an estimated farm intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.1, a sample size of approximately 250 sows was required. Sample size calculations were carried out in Win Episcope 2.0.

Data collected

A total of 549 breeder-finisher pig farms in England and Wales with more than 100 breeding sows were randomly selected from the Assured British Pig (ABP) database and invited to participate in the study. A total of 101 farmers agreed to take part in the study (18% compliance); 7 of these farms were used to pilot test the recording systems and to train observers. Data on lactating sows were collected from 89 farms. There was only one farm located in Wales so this farm was excluded from calculations of prevalence and population attributable fractions (n = 88). The Welsh farm, and a further 9 farms that were non-randomly selected for participation (5 from Scotland, recruited by Quality Meat Scotland and 4 from England recruited via their veterinarian), were included in the risk factor analysis giving a total of 99 farms.

Sow observations

On each farm, four lactating sows, one each at 3 - 7, 8 - 14, 15 - 21 and 22 - 28 days post partum, were randomly selected using random number tables (counting from the first pen/hut on the left of the entrance). A comprehensive protocol was written defining every lesion and score. Scoring systems were tested and compared on the seven on-farm training days prior to data collection. Eight trained researchers (all with science or agricultural degrees and experience with pigs) recorded data on the sows. All observers examined both indoor and outdoor housed sows.

For the purpose of classification; lesions dorsal to the elbow joint (condyle of humerus) on the fore limbs and the stifle (lateral condyle of femur) on the hind limbs were classed as body lesions while lesions ventral to these joints were classified as limb lesions. The sow's body and all four limbs were examined and all injuries were classified and their location and severity recorded (Table 1).

Observations were made of a sow's willingness to rise in the crate in response to human presence (Table 2) [12]. The sow's body condition was scored using DEFRA guidelines (Condition Scoring of Pigs, PB 3480). The size of sows in relation to the crate in which they were housed was assessed by estimating the space between the sow and the crate while the sow was standing with her snout in the feed trough. Sows were encouraged to root in their trough either by tapping the trough or by activating their drinker. The distance between a sow's back and the top of the crate was classified as less than 5 cm, 5-10 cm or more than 10 cm at this observation. The distance between a sow's tail and the back of the crate was classified as less than 10 cm, 10-20 cm or more than 20 cm.

Farrowing pen observations

Data were collected on the floor type, the condition of the floor and the use of bedding (Table 3). Indoor farrowing pen floors were divided into three areas; the pen outside the crate, the anterior part of the floor inside the crate, here after referred to as the sow lying area, and the sow dunging area.

Data checking and data analysis

A sow was defined as diseased if a lesion of score one or more (Table 1) was present. The prevalence of each different type of lesion was calculated separately. The maximum score per pig for each type of lesion was used in analysis of prevalence and associated risk factors.

The crude prevalence of each injury was calculated among the sows from the ABP English farms as follows:

The outcome variable used in the majority of risk factor analyses for each separate lesion was; 0 = sows with no lesions, 1 = sows with a lesion score 1-3. The exceptions were calluses and capped hock where, because of the high prevalence of calluses and the very mild nature of capped hock score one [14], diseased sows were classified as those with a lesion score of two or three.

Generalised binomial linear regression models with mixed effects were used with sows (level 1) nested within farms (level 2) to account for the similarity of sows within farms. MLwiN version 2.01 was used for all multilevel analysis [15]. The week of lactation was included in the models throughout the initial screening for all outcomes and forced into the final models regardless of statistical significance.

Models were built to compare indoor with outdoor housed sows. Separate models were built for sows housed indoors to investigate floor construction, bedding use and floor condition. Partly slatted floors with varying amounts of bedding were compared to investigate the effect of slat material and type of bedding on sow injury. The identity of the observer was tested in each final model to investigate whether it altered the interpretation of the fixed effects.

To check for a linear association with the outcome, continuous variables were categorised and the categories were examined for patterns of increasing or decreasing coefficients. Where the associations were non-linear the variables remained categorised. Variables were taken forward for multivariable analysis when significant at p < 0.2 [11]. Where variables were highly correlated, the most biologically plausible and useful variable, based on biological knowledge and previous research, was selected for inclusion in the model. Both forward addition and backward elimination were used to identify the variables that had a significant association (p < 0.05) with the outcome in the final model [11]. Finally, all variables rejected at the screening stage were retested in the final model to check for residual confounding [16].

The equation for the logistic models took the form:

Where pij = the probability of a lactating sow having a particular lesion, investigated with a logit link function, β0 = constant, βx is a vector of fixed effects varying at level 1 (ij) or level 2 (j), i is lactating sows, j is farms and vj and uij are the level two and level one residual variances for the distributions for sow and farm respectively.

Associations between the ordinal lesion score of different types of lesion were investigated using Pearson correlation. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare parity between indoor and outdoor housed sows. The Chi-square test was used to investigate whether lesion were more likely to be bilateral than by chance. The population attributable fractions for limb and body lesions were calculated from the ABP farms in England using the formula:

Where AFp is the population attributable fraction for each floor type, RD is the risk of a lesion in the exposed group minus the risk in the reference category group, p(E+) is the proportion of sows on a floor type and p(D+) is the proportion of sows with the lesion on a floor type [11]. Fractions are converted to percentages and summed across the floor types to calculate the total reduction possible if all sows were housed on the reference floor type.

Results

Herd, pen and sow characteristics

The study was carried out between 23 September 2003 and 2 August 2004. Visits to indoor and outdoor herds were spread throughout the year, 4-14 farms were visited per month. In total 328 sows were examined from 99 farms; 50 from 17 outdoor farms and 278 from 82 indoor farms. Prevalence estimates were calculated from sows from 16 outdoor and 73 indoor ABP English farms where complete data were available. See Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 for exact n values. The median herd size of the ABP English farms was 320 (IQR 220, 475) breeding sows (mean = 409).

All sows kept outdoors were housed in huts set on soil with deep straw bedding and access to an outdoor paddock. Of the 278 sows housed indoors on 82 farms, 12.2% (34) were kept on solid concrete floors with bedding, 21.6% (60) on partly slatted floors with bedding, 51.8% (144) on partly slatted floors without bedding and 14.4% (40) on fully slatted floors. During the previous gestation all outdoor housed sows were housed outdoors on soil, 10% of the indoor housed sows were housed on slatted floors and 90% were housed on solid concrete floors with bedding. Body condition score ranged from 1.5 to 4 with a mean of 2.9 (SD 0.5), 88% of the sows were score 2.5-3.5. The sows' parity ranged from 1-14 with a median of 3 (IQR 2, 4). Parity did not differ significantly between indoor and outdoor housed sows (U = 0.37, p = 0.71). However, parity was unknown for 20.0% of the sows.

Prevalence of limb and body lesions

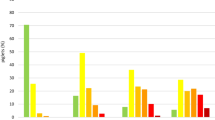

The prevalence of wounds, calluses, bursitis and capped hock on the limbs of 279 sows was 18.3% (51), 84.9% (237), 36.9% (103) and 57.0% (159) respectively. Wounds and bursitis were more prevalent on the hind limbs whilst calluses were more prevalent on the fore limbs. The prevalence of lesions on the right and left limbs was very similar and all limb lesions were significantly more likely to be bilateral then by chance (Table 4). The modal maximum lesion score was one for wounds and capped hock and two for calluses and bursitis (Table 4). The farm level prevalence of wounds, calluses, bursitis and capped hock was 37.6%, 94.1%, 71.8% and 85.9% respectively.

The prevalence of scars and new body lesions in 288 indoor and outdoor housed sows was 35.4%; 17.7% of sows had scars and 19.8% had new lesions. The prevalence of new lesions on the shoulders was 10.4% and the prevalence elsewhere on the body (hip, spine or tail area) was 11.7% (Table 5). The farm level prevalence of body lesions overall was 66.7%.

Body lesions at all locations were more prevalent and larger (higher score) in sows housed indoors compared with sows housed outdoors (Table 6).

Only one of the 39 sows housed outdoors had a new body lesion, the rest had old scars. The prevalence of limb and body lesions varied by floor type, floor condition, space in the crate, sow body condition and responsiveness to humans (Tables 7 and 8).

Risk factors associated with limb lesions in lactating sows

Wounds

No wounds on the limbs were observed in outdoor housed lactating sows. In indoor housed sows the risk of wounds on the limbs reduced with increasing week of lactation. There was an increased risk of wounds on the limbs associated with fully slatted floors, and a non significant trend for an increased risk on partly slatted floors with no bedding, compared with solid concrete floors with bedding. There was a reduced risk of wounds on the limbs on floors with dry slurry in the sow lying area (Table 9).

Calluses

There was a reduced risk of calluses in lactating sows housed outdoors compared with sows housed indoors (OR 0.1, CI 0.1, 0.2). In lactating sows housed indoors, there was a trend for the risk of calluses to increase with increasing week of lactation but the CI included unity. There was an increased risk of calluses in sows housed indoors on partly slatted floors with bedding, partly slatted floors with no bedding and fully slatted floors compared with solid concrete floors with bedding. There was a decreased risk of calluses in sows in crates with 5 - 10 cm, or more than 10 cm between the sows back and the top of the crate compared with sows with less than 5 cm (Table 9).

Bursitis

There was a reduced risk of bursitis associated with sows housed outdoors compared with sows housed indoors (OR 0.2, CI 0.1, 0.6). In sows housed indoors, the risk of bursitis increased with increasing week of lactation and decreased with increasing sow body condition. Sows that were 'dull and unresponsive' to human presence had an increased risk of bursitis compared with sows that were 'bright, alert and responsive' (Table 9).

Capped hock

There was a reduced risk of capped hock associated with sows housed outdoors compared with sows housed indoors (OR 0.1, CI 0.1, 0.6). Among indoor housed sows, an increased risk of capped hock was associated with partly slatted floors with no bedding and fully slatted floors compared with solid concrete floors with bedding. Sows that were classified as 'may be dull' had an increased risk of capped hock compared with sows that were 'bright, alert and responsive'. There was a trend for an increased risk of capped hock with increasing body condition, but the CI included unity. A reduced risk of capped hock was associated with floors with a covering of dry slurry in the sow lying area (Table 9).

Risk factors associated with body lesions in lactating sows

Body lesion scars

There was a positive association between body lesion scars and the parity of the sow (OR 1.2, CI 1.1, 1.4). No other associations were detected between floor type, crate size or sow behaviour and body lesion scars.

New shoulder lesions

There was only one outdoor housed sow with a new shoulder lesion, so there were insufficient data to calculate an estimate of risk between the prevalence outdoors (2.4%) and indoors (12.1%). Indoors, there was a trend for a decreasing risk of new shoulder lesions with increasing week of lactation, but the CI included unity. The risk of new shoulder lesions reduced as the space between the sow's tail and the back of the crate increased and there was a non significant trend for a decreased risk of new shoulder lesions with increasing body condition. The risk of new shoulder lesions increased as responsiveness to human presence decreased. An increased risk of new shoulder lesions was also associated with a lying area that was damaged or had a covering of wet slurry compared with clean, dry, undamaged floors (Table 10).

New hip, spine and tail lesions

None of the outdoor housed sows in the risk factor analysis had a new lesion on the hip, spine or tail. In indoor housed lactating sows the risk of new lesions on the hips, spine or tail reduced as the space within the crate increased. There were non significant trends for an increased risk of hip, spine and tail lesions associated with fully slatted floors, compared with solid concrete floors, and a decreased risk with increasing body condition (Table 10).

Model fit and observer differences

The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic indicated that the differences between the observed and predicted values in the models were generally small (Tables 9 and 10). Graphs of predicted verses observed values illustrated that there was a trend for the models to under predict the prevalence of limb lesions but over predict the prevalence of body lesions in the higher deciles (Figure 1). Controlling for observer or time of year the data were collected did not alter the interpretation of the fixed effects in any models.

Associations between limb and body lesions and slat materials and bedding type

Having accounted for floor type there were no significant associations between slat material (metal or plastic) or bedding type (wood shavings or straw) and the prevalence of any limb or body lesions in indoor housed lactating sows (data not shown).

Correlations between lesions

At a significance level of p < 0.01, calluses were positively correlated with wounds on the limbs, capped hock and new shoulder lesions. New lesions on the hip, spine or tail were positively correlated with bursitis. Additional correlations at a 5% significance level are presented in Table 11. Overall the R values were low and explained less than 20% of the variation between the paired variables (Table 11).

Correlations between parity, body condition and crate space

As the parity of the lactating sow increased, the body condition increased (r = 0.20, df = 219, p < 0.05) and the space in the crate decreased (between the sow's back and the top of the crate; r = -0.37, df = 219, p < 0.05, between the sow's tail and the back of the crate; r = -0.28, df = 219, p < 0.05). Sows that had less space within the crate between the sow's tail and the back of the crate were less likely to respond to human presence (r = 0.13, df = 278, p < 0.05).

Population attributable fractions

Based on the association between floor type and limb and body lesions reported in the current study, the prevalence of injuries in the diseased population would be reduced by between 32% and 100% (depending on the type of lesion, see 'total reduction' in Table 12) if sows currently housed indoors during lactation were housed outdoors. This also assumes that sows would be housed outdoors during pregnancy as for the outdoor housed lactating sows in the current study. For all types of limb and body lesions the largest proportion of lesions was attributable to part slatted floors with or without bedding (Table 12).

Discussion

This current study is, to the authors' knowledge, the first cross-sectional study of the prevalence of limb and body lesions in lactating sows on commercial English pig farms. Previous studies have been conducted in other countries and carried out on experimental units or with small numbers of farms or sampled a different population, e.g. culled sows or included pregnant sows [1–3, 6, 9]. As such the current study provides a useful benchmark for future work.

The farms in the current study are thought to be a reasonable representation of the English pig farm population in 2003-2004. The spatial location of farms reflects the location of pig farms in England with more farms sampled from the pig dense areas of North Yorkshire and East Anglia [17]. While only 17% of the study farms housed pigs outdoors, these farms housed approximately 30% of the breeding sows in the study herds, which was similar to the indoor: outdoor pig ratio in the British herd in June 2003 [18]. The mean herd size of the study farms (409 sows) was larger than the mean herd size (220 sows) of farms fitting the selection criteria in the national herd in 2003 (DEFRA June 2003 statistics, personal communication) but this might reflect the fact that herd sizes were increasing in Britain during this period [18]. It is possible that larger herds might have biased the data towards newer floors and more intensive systems. This could affect the prevalence estimates but would not have an impact on the associations between floors and lesions presented.

Assured British Pigs was the best sampling frame available, reportedly representing 90% of the national herd [19]. Sampling members of a farm assurance scheme might have resulted in a bias for farms with higher health and welfare standards. However, due to the high coverage of ABP, much of the variation in the population is captured within the sampling frame. Compliance in the current study was voluntary, which again may have biased the sample towards motivated farmers with higher standards. This could mean that the prevalence values presented from the current study underestimate the prevalence of limb and body lesions in the national herd but it is unlikely that this would bias associations between exposures and outcomes.

The number of sows in the prevalence calculations, 279 for limb lesions and 288 for body lesions, was less than the 400 specified in the study design as we did not manage to recruit 100 farms, and did not collect full data from four sows on all farms. This is likely to have increased the error around the prevalence estimates from 5% to around 7%. The sample size for prevalence calculations of lactating sows housed outdoors was low (n = 35-41 depending on outcome, from 16 farms). However, this study does provide useful information on which further work might be based. The sample size used in the risk factor analysis was sufficient to detect a 3 fold difference in risk between the exposed and unexposed sows and many useful hypotheses were generated.

The prevalence of limb and body lesions in indoor housed lactating sows was high, while the prevalence in sows housed outdoors was significantly lower (where tested). It is likely that soil and deeply bedded lying areas protect the sows from limb and body lesions. A similar pattern was reported in these sows' preweaning piglets [20]. Although analysis of a larger sample would be required to be confident this finding applied to all sows on outdoor farms, the association between injuries and slatted and unbedded floors makes this a plausible hypothesis for future studies.

As in previous studies [1, 3, 4, 9], there was an overall trend for the risk of calluses, capped hock and limb wounds to increase as the proportion of slatted floor in the farrowing crate increased and the quantity of bedding decreased. The risk of bursitis did not differ with floor type, however the prevalence of bursitis increased the longer the sow had been in the farrowing crate, suggesting that all floor surfaces were sufficiently hard to cause bursae to develop.

In addition to the effect of floor type, there was an increased risk of bursitis, capped hock and shoulder lesions in sows that were less responsive to human presence (classified as 'may be dull' or 'dull and unresponsive'). This might occur because these sows spent more time lying down because rising was difficult, e.g. slippery floors, or because once sows develop these lesions, they may experience sufficient discomfort to discourage them from rising to their feet.

It is unclear why a film of dry slurry on the floor reduced the risk of wounds on the limbs and capped hock. It is possible that the coating of dry dung made the floor less slippery, less abrasive or less hard or that a coating of dung on the sows' limbs made it difficult to detect lesions. It is possible that there might be misclassification of sows housed outdoors for this same reason. To eliminate this source of error it would be necessary to clean each sow before examination. In this cross sectional study time constraints meant that this was not feasible.

Sows that had less space in the crate had an increased risk of body lesions and calluses on the limbs, possibly because they were more likely to injure themselves against the crate whilst standing [5] or because it is harder for them to change position and move from lying to standing. Higher parity was correlated with higher body condition and therefore older sows had less space in the crate and were at increased risk of developing body lesions and calluses. Parity was not included in the final models because of the co-linearity between these variables and because parity is not a useful variable when considering intervention strategies (parity will increase in all breeding sows). The latter two explanatory variables suggest that larger sows should be kept in larger crates to minimise risk of injury. There were probably no detectable correlations between scars of old body lesions and the sow's current environment because some of these scars were from lesions that occurred in previous lactations.

There might be a reduced risk of bursitis with increasing body condition because subcutaneous fat protects against bursitis [21] or makes bursitis harder to detect. Conversely, there was a trend for increased body condition to be associated with an increased risk of capped hock. This might have occurred because heavier or older sows are at increased risk of capped hock but it can not be ruled out that there might have been a misclassification of sows with fatty hocks. The different risks for the two lesions suggests that, as proposed for finishing pigs [14], capped hock and bursae are aetiologically distinct.

As reported in several previous studies [4, 6–9], there was a trend for the risk of wounds on the limbs and body to increase in sows with poorer body condition, where there is less subcutaneous fat over the bony protuberances. This might not have reached significance in the current study because the majority of sows in this sample were in good body condition therefore a larger sample would be required to detect a significant effect. We propose that the good body condition of lactating sows arises from the good body condition of loose group-housed gestating sows that have to be fed well to avoid bullying. Sow body condition in the British breeding herd appears to be higher and more uniform than 10 - 15 years ago (Green, personal observation). Wet and rough floors probably increased the risk of shoulder sores, as reported in previous studies [4, 6, 9, 22], because moisture softened the skin and the rough floor surface was abrasive.

The prevalence of wounds on the limbs and body was highest in the first week of lactation in indoor housed sows (no sows were examined until three days post partum by which time they are likely to have been in the crate for around eight days). This might have occurred because when sows first entered the crate they were unaccustomed to having their movement restricted and this increased the risk of injury [23, 24] and also sows spent a large amount of time lying recumbent during the first days post partum [9, 22].

Conclusion

The sample of outdoor housed sows in this study had the lowest prevalence of limb and body lesions. In sows housed indoors there was a general trend for an increased risk of limb and body lesions in lactating sows housed on slatted floors compared with those housed on solid concrete floors with bedding. Sows that were less responsive to human presence and sows that had the least space to move within their crates had an additional increased risk of developing these lesions.

Abbreviations

- (OR):

-

Odds ratio

- (CI):

-

Confidence interval

- (IQR):

-

Interquartile range

- (SE):

-

Standard error

- (Var.):

-

Variance

- (ABP):

-

Assured British Pigs

- (DEFRA):

-

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

References

Edwards SA, Lightfoot AL: The effect of floor type in farrowing pens on pig injury II Leg and teat damage in sows. British Veterinary Journal. 1986, 142 (5): 141-145.

von Berner H, Hermans W, Papsthard E: Diseases of the hind legs on pigs with regard to bursitis and their relation to the type of floor. Berliner und Munichener Tierarztliche Woschenschrift. 1990, 103: 51-60.

Leeb B, Leeb C, Troxler J, Schuh M: Skin lesions and callosities in group-housed pregnant sows: animal-related welfare indicators. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica - Section A: Animal Science, SUPPL. 2001, 82-87. 10.1080/090647001316923126.

Bonde M, Rousing TJ, Badsberg H, Sørensen JT: Associations between lying-down behaviour problems and body condition, limb disorders and skin lesions of lactating sows housed in farrowing crates in commercial sow herds. Livestock Production Science. 2004, 87: 179-187. 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2003.08.005.

Curtis SE, Hurst RJ, Widowski TM, Shanks RD, Jensen AH, Gonyou HW, Bane DP, Muehling AJ, Kesler RP: Effects of sow-crate design on health and performance of sows and piglets. Journal of Animal Science. 1989, 67: 80-93.

Zurbrigg K: Sow shoulder lesions: Risk factors and treatment effects on an Ontario farm. Journal of Animal Science. 2006, 84: 2509-2514. 10.2527/jas.2005-713.

Knauer M, Stalder KJ, Karriker L, Baas TJ, Johnson C, Serenius T, Layman L, McKean JD: A descriptive survey of lesions from cull sows harvested at two Midwestern U.S. facilities. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2007, 82: 198-212. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.05.017.

Karlen GAM, Hemsworth PH, Gonyou HW, Fabrega E, Strom AD, Smits RJ: The welfare of gestating sows in conventional stalls and large groups on deep litter. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2007, 105: 87-101. 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.014.

Davies PR, Morrow WEM, Miller DC, Deen J: Epidemiologic study of decubital ulcers in sows. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1996, 208: 1058-1062.

Mouttotou N, Hatchell FM, Green LE: Prevalence and risk factors associated with adventitious bursitis in live growing and finishing pigs in south-west England. Preventative Veterinary Medicine. 1999, 39: 39-52. 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00141-X.

Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H: Veterinary Epidemiological Research. Publisher AVC, Charlottetown; 2003.

Main DCJ, Clegg J, Spatz A, Green LE: Repeatability of a lameness scoring system for finishing pigs. The Veterinary Record. 2000, 147: 547-576.

Mouttotou N, Hatchell FM, Green LE: Adventitious bursitis of the hock in finishing pigs: prevalence, distribution and association with floor type and foot lesions. The Veterinary Record. 1998, 142: 109-114.

KilBride AL, Gillman CE, Green LE: A cross-sectional study of the prevalence and associated risk factors for capped hock and the associations with bursitis in weaner, grower and finisher pigs from 93 commercial farms in England. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2008, 83: 272-284. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.08.004.

Rasbash J, Browne W, Goldstein H, Yang M, Plewis I, Healy M, Woodhouse G, Draper D, Langford I, Lewis T: A users guide to MLwiN, Version 2.1, Multilevel Models Project. Institute of Education, University of London, UK; 2000.

Cox DR, Wermuth N: Multivariate dependencies; models, analysis and interpretation. Publisher Chapman and Hall. London; 1996.

KilBride AL: An epidemiological study of foot, limb and body lesions and lameness in pigs. University of Warwick, Biological Sciences;2008.

June census data, 2003. [http://www.defra.gov.uk/esg/work_htm/publications/cs/farmstats_web]

Fearne A, Walters R: The costs and benefits of farm assurance to livestock producers in England Final report for Meat and Livestock Commission. Research CfFC: Imperial College London, Wye; 2003.

KilBride AL, Gillman CE, Ossent P, Green LE: A cross sectional study of prevalence, risk factors and population attributable fractions for foot and limb lesions in preweaning piglets on commercial farms in England. BMC Vet Res. 2009, 5 (1): 31-10.1186/1746-6148-5-31.

Smith WJ: A study of adventitious bursitis of the hock of the pigs. University of Edinburgh; 1993.

Davies PR, Morrow WEM, Rountree WG, Miller DC: Epidemiologic evaluation of decubital ulcers in farrowing sows. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1997, 210: 1173-1178.

Boyle LA, Leonard FC, Lynch PB, Brophy P: Effect of gestation housing on behaviour and skin lesions of sows in farrowing crates. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2002, 76: 119-134. 10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00211-8.

de Koning R: Injuries in confined sows. Incidence and relation with behaviour. Annales de Recherches Veterinaires. 1984, 15: 205-214.

Acknowledgements

DEFRA funded this project (AW0135). We thank Assured British Pigs and Quality Meat Scotland for assistance recruiting farmers and the farmers who kindly participate in the project. We would like to thank the field technicians and research staff who helped collecting the data; Jane Slevin, Kerry Woodbine, Megan Turner, Emma Novell, Fiona Boyd, Charlotte Boss, Maureen Horne, Martin Crockett, Lucy Reilly and Bart van den Borne.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ALK: participated in the study design, data collection and data management, carried out the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. CEG: provided advice and assistance with data analysis. LEG: conceived the project, designed the study, oversaw project management and supervised statistical analysis and assisted with preparation of the manuscript. All authors have read and contributed to the final draft of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

KilBride, A.L., Gillman, C.E. & Green, L.E. A cross sectional study of the prevalence, risk factors and population attributable fractions for limb and body lesions in lactating sows on commercial farms in England. BMC Vet Res 5, 30 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-5-30

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-5-30