Abstract

Background

Bovine tuberculosis (bTB) remains a significant problem in some parts of Spain largely because of contacts between cattle and wildlife reservoirs in extensive grazing systems. European Wild boar (Sus scrofa) is one of the species involved in the transmission of the disease to other species. Fast and simple detection methods would be critical for assessing infection prevalence, study the mechanisms of pathogen transmission and monitoring the effects of TB control measures.

Results

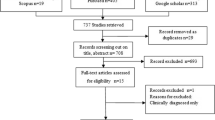

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect antibodies against Mycobacterium bovis in wild boar serum was developed and validated on 185 sera from TB positive and negative wild boar. Based on antigen inoculation of captive animals as well as tuberculosis compatible lesions, culture results and molecular analysis of hunted individuals, animals were allocated into two groups: tuberculosis positive group and tuberculosis negative group. After optimization of the positive to negative ratio using different combinations of serum dilutions and conjugate concentrations, the test yielded a sensitivity of 72.60% and a specificity of 96.43% for the best cut-off.

Conclusion

Although some negative group animals showed an ELISA positive reaction (< 3%), this assay showed a high potential for accurate diagnosis of TB in wild boar, as its large dynamic range supported a good discriminatory power and a satisfactory balance between sensitivity and specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bovine tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium bovis and other closely related mycobacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, is endemic in many countries. These mycobacteria can infect a wide range of domestic and wild animals [1–3]. Wild animals become increasingly important in the spread and maintenance of M. bovis infection, especially when the efforts to eradicate the disease in livestock have reduced its incidence in domestic cattle [2, 4]. The existence of wildlife tuberculosis (TB) reservoirs and the difficulty of controlling the disease in these species is the most important complication in eradication programs [3]. Well known examples of wildlife TB reservoirs include the badger (Meles meles) in the United Kingdom and Ireland [5, 6], the brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) in New Zealand [3], the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the north of the United States of America [7], the buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in South Africa [8, 9], or the bison (Bison bison) in Canada [10].

In Spain, TB prevalence is relatively low in cattle (0.42 in 2006), but the infection persists in other livestock including goats and free-ranging swine, and there is a wide range of wild animal species susceptible to this disease [11]. Previous research suggested inter-specific transmission of the M. tuberculosis complex among wild ungulates and livestock [11–14]. The European wild boar (Sus scrofa) is one of the ungulates involved in the epidemiology of tuberculosis in Spain. Recent epidemiological, pathological and microbiological evidence strongly suggests that, at least in Spanish Mediterranean ecosystems, wild boar are able to maintain TB infection in the wild and most likely can transmit the disease to other species, acting as a true wildlife reservoir [15]. Depending on risk factors such as host age and management including feeding and fencing, wild boar TB prevalence ranges based on gross pathology from 18 to 100% [16, 17]. The diagnosis of M. bovis infection in live animals generally depends on the cellular immune response to M. bovis antigens in the first stages of the infection [18]. The most usual technique is the hypersensitivity test, based on the intradermal injection of raw antigens [19–21]. This skin testing technique, described by Robert Koch, is still the most widely used tuberculosis diagnostic method in livestock. It is also used in wild ruminants [22, 23]. However, skin tests have a limited sensitivity, and non specific reactions may occur in animals sensitized by mycobacteria other than those of the M. tuberculosis complex [24, 25].

In wild animals, any diagnostic test has an associated risk during the capture, both for the people who handle the animal and for the animal itself, due to handling stress and injuries. Moreover, preliminary results of skin testing in wild boar of known TB status suggest a low sensitivity (unpublished data). Thus, the possibility of a test based on a single sampling would be highly desirable for assessing the prevalence, studying the mechanisms of transmission and monitoring the effects of control measures.

While the delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction is indicative of infection or exposure, antibody formation appears to be more closely related to the extent of bacterial multiplication and antigenic load in the infected individual. ELISA testing is not routinely used in bovine TB control programs mainly due to a reduced sensitivity [26], although it has been suggested to be used as a complement to the tuberculin test, especially for the detection of anergic tuberculous cattle [27, 28].

The aim of this study was to develop and validate an ELISA test for the detection of Mycobacterium bovis antibodies in wild boar serum. To achieve this goal, the humoral immune response measured by this test was first measured in captive wild boar sensitized with inactivated bacterial antigens and then results were validated with sera obtained from wild boar of known microbiological TB status.

Results

Humoral response to mycobacterial antigens

The two M. bovis immunized wild boars (WB1 and WB4) developed a large increase in the level of antibodies between pre-immunization (S1) and 30 days post-immunization (S2) serum samples while showing a much smaller increase at 90 days post-immunization (Table 1; Figure 1). The other two wild boar, immunized with M. avium (WB3) and M. paratuberculosis (WB2), showed a much smaller increase in the antibody level against bovine PPD between the pre-immunization sampling and controls S2 and S3 (Table 1).

The optical densities (OD) obtained showed better discrimination at greater dilutions, but at serum dilutions higher than 1/200 we observed a decrease in OD values converging to blank readings. Sera reacted with both conjugates, Protein G and Protein A, but OD values were more homogeneous and the discrimination was higher with Protein G. Finally, serum dilution and conjugate Protein G concentration combinations showing the highest increases between S1 and S2 were retained for validation with the known status sera: 1/10–0.05 μg/ml, 1/200–2.5 μg/ml, 1/200–0.5 μg/ml and 1/200–0.05 μg/ml.

Known status sera analysis and determination of cut-off value

The summary of ELISA results in Table 2 shows that at the highest semi-sum, specificities were > 93% and sensitivities > 69% in all combinations. The best semi-sum was obtained at 1/200 serum dilution and 2.5 μg/ml conjugate concentration. These dilutions yielded the highest sensitivity (80.26%) among all tested combinations, but at the same time the specificity was reduced to 95.61%. The next best combination was that of a 1/200 serum dilution and a conjugate concentration of 0.05 μg/ml, with 72.60% sensitivity and 96.43% specificity.

In order to assess the reproducibility of the ELISA and to validate the test, the two latter combinations (1/200 and 2.5 μg/ml, and 1/200 and 0.05 μg/ml) were repeated in two different days. It was observed that the replicates in case of the combination 1/200 and 0.05 μg/ml varied less than those of the other combination. Besides, the coefficient of variation (CV) between days of each test was smaller and the dynamic range was broader too for the 1/200 and 0.05 μg/ml combination (Table 3).

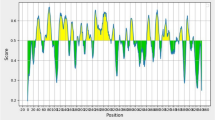

Figure 2 shows the dynamics of sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic value semi-sum, SeDI and SpDI values for the ELISA with 1/200 and 0.05 μg/ml sera/conjugate combination. It can be seen that the range between 0.115 and 0.655 has diagnostic values over 80%, with a slightly higher primary peak between 0.195 and 0.275 and a secondary one between 0.415 and 0.475. The SeDI and SpDI peak on both sides of the first peak, and indicate the optimal performance when either sensitivity or specificity is the main focus for the test. If a good balance is the goal, then an intermediate value should be the choice. In this case, and taking into account the distribution shown in the histogram (Figure 3) a value at around 0.2 appears to provide the best trade-off. This figure shows that there are at least bimodal distributions both for reference negative and positive sera. This bimodal distribution is less clear for the negative set since all but four sera locate below the 0.2 cut-off. The positives have a highly polarized distribution with markedly high modes at both ends of the EI range and an almost continuous distribution between them. Therefore a cut-off of 0.200 was finally chosen as the one yielding the best balance between sensitivity and specificity and locating to a region where no values were found thus indicating a biological separation between EI populations.

Discussion

To date, studies are not available on the experimental use of antigens to characterize the immune response of wild boar and pigs against M. bovis. Herein, inactivated mycobacterial antigens were successfully used to stimulate a specific humoral immune response in healthy wild boar. Injection of the antigens caused an increase of specific antibodies, but the administration of a second antigen dose did not raise the antibody levels so much. A strong cross reaction between antibodies specific for M. avium and M. avium paratuberculosis (WB 2 and WB 3) and the bovine PPD ELISA was not observed except to some extent for WB2 after the boosting. Thus, the immunization assay provided negative and positive M. bovis control sera to use in the development of the ELISA, as well as for reference in the future.

It is generally recognized that humoral immunity is not important for tuberculosis diagnosis [29], but it may nonetheless be useful to detect animals with severe illness since antibody concentration is related to lesion distribution and severity, as well as to the number of bacilli [18, 22, 26, 30–32]. Mycobacterial infections induce antibody production in ruminants, but the profile of immunoglobulin (Ig) expression in M. bovis infected animals is poorly understood [33–36]. In previous studies, Ig heavy and light chains were up-regulated in European wild boar infected with M. bovis [37]. However, serum determinations suggested elevated levels of IgG in uninfected wild boar when compared to M. bovis infected animals [38]. The mechanism of Ig differential expression in M. bovis infected wild boar is unknown but may reflect different stages during mycobacterial infection. Furthermore, differential gene expression analysis in response to mycobacterial infection in wild boar suggest that antibody responses against M. bovis may be important in natural infections of wildlife species and may be used for bTB surveillance and treatment monitoring [35, 39–41].

Previous studies using ELISA tests achieved 74% sensitivity and 90% specificity in cattle [26], and 79% to 98% specificity and 37% sensitivity in ELISA used in badgers [41–43], although the latter was increased for badgers with progressive tuberculosis [44]. In addition, a positive ELISA result in badgers was correlated with an enhanced likelihood of a future positive culture result [45]. Various mycobacterial antigens have also been used for bovine tuberculosis ELISA in other studies. This includes for example ELISA based on MPB70 and MPB83 in cattle, which have reported specificities of 89% and 96.4%, and sensitivities of 18.1% and 37.5% [46, 47]. The results obtained in the current study, thus, indicate that the ELISA performance was substantially better for wild boar, especially in terms of sensitivity (72.60%) and without a significant loss in specificity (96.43%) despite the fact that it is generally recognized that the sensitivities and specificities of ELISA protocols for serodiagnosis of bovine tuberculosis are low as compared to those for other diseases [48].

At the chosen cut-off, there were a few reference negative animals that had medium level antibody reactivity against bovine PPD. It might be possible that some of these animals were infected individuals without visible lesions and bacteria not found, or true non-infected but exposed to M. bovis infection, that is, potentially resistant animals. Actually, ELISA positive results are usually considered only as evidence of exposure [17] and not necessarily of current infection. Infections with other mycobacteria causing cross-reactivity cannot be completely ruled out although, given the origin of the animals in infected areas and the EI gap to the rest of negative controls, we think they are less likely to be involved. On the other hand there were animals where M. bovis was isolated that had very low EI readings. These animals might represent recently infected individuals not having developed yet a humoral immune response or anergic animals with limited immune responses due to poor body condition.

Conclusion

We conclude that the use of the serological ELISA test developed herein may contribute to the diagnosis of TB in wild boar and probably also in pigs, with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity and without the need to handle the animals twice as in the skin test. This ELISA test could be used in the control of TB in wild boar through "test & cull" schemes and in large-scale surveys [49]. These results support the use of the ELISA test to complement other techniques based on cellular response to characterize mycobacterial infection in wild boar.

Methods

Reference sera

Wild boar immunization

In order to obtain serum controls to be used in the ELISA, four captive adult wild boars living in a M. bovis free area were used. On day 0, wild boar 1 (WB1) and 4 (WB4) were immunized by the subcutaneous route with 1 ml of a suspension containing 103–106 colony-forming units (CFU; 2.5 mg) of heat inactivated M. bovis. Wild boar 3 (WB3) was immunized with 1 ml (103–106 CFU) of heat inactivated M. avium (M. bovis and M. avium were kindly provided by CZ Veterinaria), and wild boar 2 (WB2) with 1 ml (2.5 mg) of heat inactivated commercial M. avium paratuberculosis vaccine (Gudair® CZ Veterinaria, S.L., Spain). Prior to immunization a serum sample (S1) was taken from each animal. Thirty days later a second serum sample (S2) was taken and all the animals were re-immunized in the same way. Ninety days later a third serum sample (S3) was taken from the four animals. All sera were stored frozen at -20°C until used for testing. All animal use was supervised by the Neiker Committee on Animal Experimentation in accordance with Spanish laws.

Wild Boar of known TB status

In order to validate the ELISA, 185 sera obtained from known TB status cases (known status sera) were analyzed. This material included 73 sera from naturally TB positive wild boar, defined as individuals with both tuberculosis compatible lesions [50] and M. tuberculosis complex isolation and PCR confirmation (data not shown). The material also included 112 sera from TB negative wild boar, defined as animals with no visible TB-compatible lesions and negative culture. These sera were analyzed with the optimized ELISA protocol, using S3 of WB1 or WB4 as positive control and S1 as negative control.

Indirect ELISA optimization

Bovine tuberculin purified protein derivative (bovine PPD) (CZ Veterinaria, S.L., Spain) was diluted to 5 μg/ml in carbonate buffer (63 mM, pH 9.6). Plates (High binding ELISA microplate, Greiner bio-one, Germany) were coated with 100 μl of diluted PPD and used in fresh, without any storage. Serum samples and controls, were adsorbed (1/1) with Mycobacterium phlei saline suspension (5 gr/l; Dr. O. Fuentes, INIA, Spain), to remove non-specific anti-Mycobacterium spp. antibodies. After an overnight incubation at 4°C, samples were diluted in PBS-Tween (0.14 M NaCl; 3 mM KCl; 10 mM Phosphate buffer; 0.05 Tween 20; pH 7.4) and 100 μl of each dilution were added in duplicate in contiguous wells of the bovine PPD coated plate and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After three washings with PBS-Tween, 100 μl of Protein A or G were added and incubated for two hours at room temperature. Again after three washings, 100 μl of ABTS substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to each well and incubated for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Optical densities (OD) were read with 405 and 450 nm filters (MultiskanEX, Thermolabsystems). Sample result was expressed as an ELISA index (EI) that was calculated as the ratio of the mean sample OD to the mean OD of the positive controls.

Optimal dilutions of sera were determined by the evaluation of the reactivity of serial dilutions (1/10; 1/100; 1/200; 1/500; 1/1000 and 1/2500) and in combination of serial dilutions of Protein G or Protein A conjugated with recombinant peroxidase from Streptococcus sp. (2.5 μg/ml; 1 μg/ml; 0.5 μg/ml; 0.05 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) with reference serum samples S1, S2 and S3 from the four immunized wild boar analyzed in duplicate. The serum dilution and Protein G concentration at which the ratio between S2 and S1 ODs were higher and apparently more representative were selected for testing the whole set of known status sera. These sera were then tested only at 4 different combinations (serum dilution-PrG concentration): 1/10–0.05 μg/ml, 1/200–2.5 μg/ml, 1/200–0.5 μg/ml and 1/200–0.05 μg/ml.

Indirect ELISA validation

ELISA indices of the whole set of known status sera were entered in a spreadsheet (RA Juste, unpublished), that allowed to calculate sensitivity and specificity for each cut-off. This spreadsheet also calculates the semi-sum of sensitivity and specificity (diagnostic value ranging from 0 to 100) and the ratios of specificity to sensitivity (specificity discriminating index – SpDI) and of sensitivity to specificity (sensitivity discriminating index – SeDI). The spreadsheet also plots all the values in a single graph that allows seeing at once the behaviour of all these relevant variables along the dynamic range of the test. A verification of these analyses was made using the SigmaPlot (Addlink, Barcelona, Spain) graphics package that was also used to plot the positive and negative known status sera EI histogram and to calculate the 95% sensitivity and specificity confidence intervals at each cut-off.

The final cut-off for the test was chosen as that that yielded the highest semi-sum, was located in a region where small changes in its numerical value did not change substantially the semi-sum (Figure 2), and in the histogram was located in the widest gap without values (Figure 3).

References

de Lisle GW, Bengis RG, Schmitt SM, O'Brien DJ: Tuberculosis in free-ranging wildlife: detection, diagnosis and management. Rev Sci Tech. 2002, 21: 317-334.

Morris RS, Pfeiffer DU, Jackson R: The epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infections. Vet Microbiol. 1994, 40: 153-177. 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90053-1.

O'Reilly LM, Daborn CJ: The epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infections in animals and man: a review. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995, 76 (Suppl 1): 1-46. 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90591-X.

Aranaz A, Liebana E, Mateos A, Dominguez L, Vidal D, Domingo M, Gonzolez O, Rodriguez-Ferri EF, Bunschoten AE, van Embden JD, Cousins D: Spacer oligonucleotide typing of Mycobacterium bovis strains from cattle and other animals: a tool for studying epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996, 34: 2734-2740.

Cheeseman CL, Wilesmith JW, Stuart FA: Tuberculosis: the disease and its epidemiology in the badger, a review. Epidemiol Infect. 1989, 103: 113-125.

Gormley E, Costello E: Tuberculosis and badgers: new approaches to diagnosis and control. J Appl Microbiol. 2003, 94 (Suppl): 80S-86S. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.9.x.

Schmitt SM, Fitzgerald SD, Cooley TM, Bruning-Fann CS, Sullivan L, Berry D, Carlson T, Minnis RB, Payeur JB, Sikarskie J: Bovine tuberculosis in free-ranging white-tailed deer from Michigan. J Wildl Dis. 1997, 33: 749-758.

de Vos V, Bengis RG, Kriek NP, Michel A, Keet DF, Raath JP, Huchzermeyer HF: The epidemiology of tuberculosis in free-ranging African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2001, 68: 119-130.

Michel AL, de Klerk LM, van Pittius NC, Warren RM, van Helden PD: Bovine tuberculosis in African buffaloes: observations regarding Mycobacterium bovis shedding into water and exposure to environmental mycobacteria. BMC Vet Res. 2007, 3: 23-29. 10.1186/1746-6148-3-23.

Choquette LP, Gallivan JF, Byrne JL, Pilipavicius J: Parasites and Diseases of Bison in Canada: 1 Tuberculosis and Some Other Pathological Conditions in Bison at Wood buffalo And Elk Island National Parks in the Fall and Winter of 1959–60. Can Vet J. 1961, 2: 168-174.

Aranaz A, De Juan L, Montero N, Sanchez C, Galka M, Delso C, Alvarez J, Romero B, Bezos J, Vela AI, Briones V, Mateos A, Dominguez L: Bovine tuberculosis (Mycobacterium bovis) in wildlife in Spain. J Clin Microbiol. 2004, 42: 2602-2608. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2602-2608.2004.

Parra A, Fernandez-Llario P, Tato A, Larrasa J, Garcia A, Alonso JM, Hermoso de Mendoza M, Hermoso de Mendoza J: Epidemiology of Mycobacterium bovis infections of pigs and wild boars using a molecular approach. Vet Microbiol. 2003, 97: 123-133. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.08.007.

Parra A, Larrasa J, Garcia A, Alonso JM, de Mendoza JH: Molecular epidemiology of bovine tuberculosis in wild animals in Spain: a first approach to risk factor analysis. Vet Microbiol. 2005, 110: 293-300. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.07.013.

Gortazar C, Acevedo P, Ruiz-Fons F, Vicente J: Disease risk and overabundance of game species. Eur J Wildl Res. 2006, 52: 81-87. 10.1007/s10344-005-0022-2.

Naranjo V, Gortazar C, Vicente J, de la Fuente J: Evidence of the role of European wild boar as a reservoir of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Vet Microbiol. 2008, 127: 1-9. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.10.002.

Vicente J, Hofle U, Garrido JM, Fernandez-de-Mera IG, Juste R, Barral M, Gortazar C: Wild boar and red deer display high prevalences of tuberculosis-like lesions in Spain. Vet Res. 2006, 37: 107-119. 10.1051/vetres:2005044.

Vicente J, Hofle U, Garrido JM, Fernandez-de-Mera IG, Acevedo P, Juste R, Barral M, Gortazar C: Risk factors associated with the prevalence of tuberculosis-like lesions in fenced wild boar and red deer in south central Spain. Vet Res. 2007, 38: 451-464. 10.1051/vetres:2007002.

Rua-Domenech R, Goodchild AT, Vordermeier HM, Hewinson RG, Christiansen KH, Clifton-Hadley RS: Ante mortem diagnosis of tuberculosis in cattle: a review of the tuberculin tests, gamma-interferon assay and other ancillary diagnostic techniques. Res Vet Sci. 2006, 81: 190-210. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2005.11.005.

Snider DE: The tuberculin skin test. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982, 125: 108-118.

Pollock JM, Girvin RM, Lightbody KA, Clements RA, Neill SD, Buddle BM, Andersen P: Assessment of defined antigens for the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in skin test-reactor cattle. Vet Rec. 2000, 146: 659-665.

Palmer MV, Waters WR, Thacker TC, Greenwald R, Esfandiari J, Lyashchenko KP: Effects of different tuberculin skin-testing regimens on gamma interferon and antibody responses in cattle experimentally infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13: 387-394. 10.1128/CVI.13.3.387-394.2006.

Griffin JF, Nagai S, Buchan GS: Tuberculosis in domesticated red deer: comparison of purified protein derivative and the specific protein MPB70 for in vitro diagnosis. Res Vet Sci. 1991, 50: 279-285.

Zomborszky Z, Kormendy B, Tuboly S, Tilly P, Horn P: The value of immunodiagnostic tests in detecting tuberculosis in an infected red deer herd and in eradication of the disease by selection. Acta Vet Hung. 1995, 43: 385-392.

Chaparas SD, Maloney CJ: An analysis of cross reactions among mycobacteria by in vivo and in vitro assays of cellular hypersensitivity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978, 117: 897-902.

Wood PR, Rothel JS: In vitro immunodiagnostic assays for bovine tuberculosis. Vet Microbiol. 1994, 40: 125-135. 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90051-5.

Ritacco V, Lopez B, Barrera L, Nader A, Fliess E, de Kantor: Further evaluation of an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1990, 37: 19-27.

Auer LA: Assessment of an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of cattle infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Aus Vet J. 1987, 64: 172-176. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1987.tb09676.x.

Plackett P, Ripper J, Corner LA, Small K, de Witte K, Melville L, Hides S, Wood PR: An ELISA for the detection of anergic tuberculous cattle. Aus Vet J. 1989, 66: 15-19. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1989.tb09706.x.

Rook GA, Hernandez-Pando R: The pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996, 50: 259-284. 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.259.

Hanna J, Neill SD, O'Brien JJ: Use of PPD and phosphatide antigens in an ELISA to detect the serological response in experimental bovine tuberculosis. Res Vet Sci. 1989, 47: 43-47.

Young DB, Mehlert A: Serology of mycobacteria: characterization of antigens recognized by monoclonal antibodies. Rev Infect Dis. 1989, 11 (Suppl 2): S431-S435.

Hanna J, Neill SD, O'Brien JJ: ELISA tests for antibodies in experimental bovine tuberculosis. Vet Microbiol. 1992, 31: 243-249. 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90082-5.

Buddle BM, Wedlock DN, Denis M, Skinner MA: Identification of immune response correlates for protection against bovine tuberculosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005, 108: 45-51. 10.1016/j.vetimm.2005.08.002.

Palmer MV, Waters WR, Thacker TC, Stoffregen WC, Thomsen BV: Experimentally induced infection of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) with Mycobacterium bovis. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2006, 18: 52-60.

Waters WR, Palmer MV, Thacker TC, Bannantine JP, Vordermeier HM, Hewinson RG, Greenwald R, Esfandiari J, McNair J, Pollock JM, Andersen P, Lyashchenko KP: Early antibody responses to experimental Mycobacterium bovis infection of cattle. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13: 648-654. 10.1128/CVI.00061-06.

Fernandez de Mera MI, Perez de la Lastra JM, Ayoubi P, Naranjo V, Kocan KM, Gortazar C, de la Fuente J: Differential expression of inflammatory and immune response genes in mesenteric lymph nodes of Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) naturally infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008, 32: 85-91.

Naranjo V, Hofle U, Vicente J, Martin MP, Ruiz-Fons F, Gortazar C, Kocan KM, de la Fuente J: Genes differentially expressed in oropharyngeal tonsils and mandibular lymph nodes of tuberculous and nontuberculous European wild boars naturally exposed to Mycobacterium bovis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006, 46: 298-312. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00035.x.

Vidal D: Analysis of serum biochemical parameters in relation to Mycobacterium bovis infection of European wild boards (Sus Scrofa) in Spain. Eur J Wildl Res. 2006, 52: 301-304. 10.1007/s10344-006-0062-2.

Waters WR, Palmer MV, Thacker TC, Payeur JB, Harris NB, Minion FC, Greenwald R, Esfandiari J, Andersen P, McNair J, Pollock JM, Lyashchenko KP: Immune responses to defined antigens of Mycobacterium bovis in cattle experimentally infected with Mycobacterium kansasii. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13: 611-619. 10.1128/CVI.00054-06.

Naranjo V, Gortazar C, Villar M, de la Fuente J: Comparative genomics and proteomics to study tissue-specific response and function in natural Mycobacterium bovis infections. Anim Health Res Rev. 2007, 8: 81-88. 10.1017/S1466252307001260.

Morris JA, Stevens AE, Stuart P, Little TW: A pilot study to assess the usefulness of ELISA in detecting tuberculosis in badgers. Vet Rec. 1979, 104: 14.

Newell DG, Clifton-Hadley RS, Cheeseman CL: The kinetics of serum antibody responses to natural infections with Mycobacterium bovis in one badger social group. Epidemiol Infect. 1997, 118: 173-180. 10.1017/S0950268896007340.

Goodger J, Nolan A, Russell WP, Dalley DJ, Thorns CJ, Stuart FA, Croston P, Newell DG: Serodiagnosis of Mycobacterium bovis infection in badgers: development of an indirect ELISA using a 25 kDa antigen. Vet Rec. 1994, 135: 82-85.

Clifton-Hadley RS, Sayers AR, Stock MP: Evaluation of an ELISA for Mycobacterium bovis infection in badgers (Meles meles). Vet Rec. 1995, 137: 555-558.

Chambers MA, Pressling WA, Cheeseman CL, Clifton-Hadley RS, Hewinson RG: Value of existing serological tests for identifying badgers that shed Mycobacterium bovis. Vet Microbiol. 2002, 86: 183-189. 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00012-3.

McNair J, Corbett DM, Girvin RM, Mackie DP, Pollock JM: Characterization of the early antibody response in bovine tuberculosis: MPB83 is an early target with diagnostic potential. Scand J Immunol. 2001, 53: 365-371. 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00874.x.

Wood PR, Corner LA, Rothel JS, Ripper JL, Fifis T, McCormick BS, Francis B, Melville L, Small K, de Witte K: A field evaluation of serological and cellular diagnostic tests for bovine tuberculosis. Vet Microbiol. 1992, 31: 71-79. 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90142-G.

Sugden EA, Stilwell K, Rohonczy EB, Martineau P: Competitive and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for Mycobacterium bovis infections based on MPB70 and lipoarabinomannan antigens. Can J Vet Res. 1997, 61: 8-14.

Gortazar C, Torres MJ, Vicente J, Acevedo P, Reglero M, de la Fuente J, Negro JJ, Aznar-Martin J: Bovine tuberculosis in Donana Biosphere Reserve: the role of wild ungulates as disease reservoirs in the last Iberian lynx strongholds. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3: e2776-10.1371/journal.pone.0002776.

Martin-Hernando MP, Hofle U, Vicente J, Ruiz-Fons F, Vidal D, Barral M, Garrido JM, de la Fuente J, Gortazar C: Lesions associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex infection in the European wild boar. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2007, 87: 360-367. 10.1016/j.tube.2007.02.003.

Acknowledgements

We thank CZ Veterinaria, S.L., Spain for providing the mycobacterial antigens used in the experiments. This work was supported by projects INIA-RTA03-074-C2 and "Control of tuberculosis in Wildlife" of Santander-Fundación Marcelino Botín (to C. G. and J. F.); Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of the Basque Government; CICYT-MEC research Grant AGL2005-07401, and FEDER (Spain). This work was made in part thanks to the agreements with OAPN and SDGSA (MMA-MRM); MAPA; Fundación Candido de Iturriaga y María de Dañobeitia and Diputaciones Forales de Vizcaya, Guipúzcoa y Álava. We would also like to thank Karpin Aventura (Iniciativas Ambientales de Euskadi, S.L.) and Alfredo Peña for their contribution in immunization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

OA and JV performed the field work and collected all the samples of the study. OA carried out the laboratory work and generated the immunological data. OA, MB, RAJ, JV and CG designed the experiment. The immunological analyses were designed by OA, MB and RAJ. MB was the project leader and coordinated and supervised all the study. RAJ participated on data analysis and study supervision. OA wrote the manuscript and JF, CG, JV, MB and RAJ contributed to draft it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Aurtenetxe, O., Barral, M., Vicente, J. et al. Development and validation of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for antibodies against Mycobacterium bovisin european wild boar. BMC Vet Res 4, 43 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-4-43

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-4-43