Abstract

Background

Photoperiod is known to cause physiological changes in seasonal mammals, including changes in body weight, physical activity, reproductive status, and adipose tissue gene expression in several species. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of day length on the adipose transcriptome of cats as assessed by RNA sequencing. Ten healthy adult neutered male domestic shorthair cats were used in a randomized crossover design study. During two 12-wk periods, cats were exposed to either short days (8 hr light:16 hr dark) or long days (16 hr light:8 hr dark). Cats were fed a commercial diet to maintain baseline body weight to avoid weight-related bias. Subcutaneous adipose biopsies were collected at wk 12 of each period for RNA isolation and sequencing.

Results

A total of 578 million sequences (28.9 million/sample) were generated by Illumina sequencing. A total of 170 mRNA transcripts were differentially expressed between short day- and long day-housed cats. 89 annotated transcripts were up-regulated by short days, while 24 annotated transcripts were down-regulated by short days. Another 57 un-annotated transcripts were also different between groups. Adipose tissue of short day-housed cats had greater expression of genes involved with cell growth and differentiation (e.g., myostatin; frizzled-related protein), cell development and structure (e.g., cytokeratins), and protein processing and ubiquitination (e.g., kelch-like proteins). In contrast, short day-housed cats had decreased expression of genes involved with immune function (e.g., plasminogen activator inhibitor 1; chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; C-C motif chemokine 5; T-cell activators), and altered expression of genes associated with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

Conclusions

Collectively, these gene expression changes suggest that short day housing may promote adipogenesis, minimize inflammation and oxidative stress, and alter nutrient metabolism in feline adipose tissue, even when fed to maintain body weight. Although this study has highlighted molecular mechanisms contributing to the seasonal metabolic changes observed in cats, future research that specifically targets and studies these biological pathways, and the physiological outcomes that are affected by them, is justified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Photoperiod is known to alter many physiologic outcomes in seasonal animals, including food intake, weight gain, and estrous. Melatonin, secreted by the pineal gland, is an important signal contributing to these seasonal responses. Melatonin secretion exhibits an obvious circadian rhythm, peaking during the dark period [1]. Over the course of a year, the peak of melatonin concentrations and the duration of high melatonin production is greatest during winter/short days (SD) and lowest during summer/long days (LD) [2]. The response to decreased daylight depends on species, however, with some gaining weight and others losing weight. For example, Siberian hamsters and meadow voles lose fat mass and total body weight (BW) with shortened days [3, 4], while Syrian hamsters, collared lemmings, prairie voles and raccoon dogs gain fat mass and total BW with SD [5–8]. Cats are sensitive to photoperiod as it relates to circulating melatonin concentrations and estrous cycling [9–11] and seasonal differences in activity levels are known to exist in feral cat populations, with increased activity during the spring/summer period [12]. Seasonal and photoperiod changes on energy intake, energy expenditure, and voluntary physical activity levels have also been recently reported in domestic cats [13, 14]. Feline obesity continues to increase in the pet population and is a risk factor for many chronic diseases. Although studying seasonal changes may provide a better understanding of energy homeostasis in cats, the mechanisms by which these changes occur in adipose tissue have not been adequately studied.

Studies in ruminants and rodents have shown that seasonal BW changes are often due to seasonal cycles in fat deposition and adipose tissue lipogenic activity and gene expression [4, 15–17]. Leptin, an important long-term BW regulator, is a common molecular target of study. Although leptin is typically positively correlated with BW, the mRNA expression and secretion of leptin also undergoes significant seasonal fluctuations. Adipose tissue leptin mRNA has been shown to increase during LD in several species, including lactating dairy cows, ovariectomized ewes, and Siberian hamsters [16, 18–20]. These increases did not necessarily correlate with BW, however, suggesting that photoperiod may override leptin responsiveness in some situations. A great example of this response has been reported in Siberian hamsters housed in LD vs. SD. In that study, food intake was altered due to photoperiod, but did not correlate with adipose tissue leptin mRNA abundance [18]. Thus, it appears that leptin sensitivity and signaling in Siberian hamsters is dependent on day length [18], with increased leptin resistance during LD [21]. Enzymes involved in adipose tissue metabolism have also been studied in several animal models, but with conflicting results [20, 22–24].

While it is clear that photoperiod impacts BW and adipose tissue metabolism, the response appears to be species-specific. Although previous studies have identified mechanisms by which ovariohysterectomy and/or dietary intervention contribute to changes in adipose tissue metabolism and BW in cats [25–27], a molecular analysis of how photoperiod affects the adipose tissue transcriptome has not yet been performed in this species. Moreover, only a few select genes or biological pathways have been typically studied in this regard. Therefore, research performed specifically in the cat using high-throughput molecular techniques to evaluate the entire adipose tissue transcriptome was justified. A commercial feline microarray is not currently available so RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), which provides a global assessment of gene expression [28, 29], was deemed to be the best strategy to use in this study. Thus, our objective was to evaluate the effects of photoperiod on the adipose transcriptome in cats as measured by RNA-seq. To test the effects of photoperiod only, and not the change in BW that often occurs with altered day length, cats were fed to maintain BW throughout the study.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to animal experimentation.

Animals and treatments

Ten healthy adult (4 yr old) neutered male domestic shorthair cats of healthy body condition (5/9 body condition score) were used. Cats were group housed for 22 hr of each day, but were isolated in individual stainless steel cages (0.61 × 0.61 × 0.61 m) for 1 hr twice daily (9:00–10:00 am; 4:00–5:00 pm) so food could be offered and individual intake measured. One group of cats (n = 5) was housed in a room measuring 12 m2 and a second group of cats (n = 5) was housed in a room measuring 26 m2. Cats had access to various toys and scratching posts for behavioral enrichment. Cats were fed a dry commercial diet (Whiskas® Meaty Selections®, Mars, Inc., Mattoon, IL) to maintain BW (within 5% of baseline BW) throughout the experiment. Water was available ad libitum throughout the experiment.

Four weeks prior to the experiment (wk -4), cats were acclimated to the diet and daily feeding schedule, and were exposed to 12 hr light: 12 hr dark. The experiment was performed using a crossover design composed of two 12-wk periods. Cats were randomly assigned to one of two groups, and with groups being randomly assigned to room. Cats remained in the same rooms throughout the experiment. Rooms were adjacent to each other in the animal facility, were maintained at the same temperature (20°C to 22°C) and humidity level (30% to 70%) throughout the study, and did not have windows (a source of natural light). For the first 12-wk period, Group 1 was exposed to 16 hr light: 8 hr dark (LD), while Group 2 was exposed to 8 hr light: 16 hr dark (SD). For the second 12-wk period, Group 1 was exposed to SD and Group 2 was exposed to LD. Daily food intake and twice-weekly BW were measured throughout the study. Food intake was adjusted to maintain BW and body condition score (9 point scale) [30] throughout the study.

Body composition, physical activity, and indirect calorimetry

Body composition, voluntary physical activity, and indirect calorimetry were measured during wk 0 and 12 as described previously [14]. Briefly, body composition (lean mass, fat mass, and bone mineral mass) was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Cats were placed in ventral recumbency and body composition was analyzed using a Hologic model QDR-4500 Fan Beam X-ray Bone Densitometer and software (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA). Voluntary physical activity was measured using Actical activity monitors (Mini Mitter, Bend, OR). Activity collars were worn around the neck for 7 consecutive d. Collars were then removed and data were analyzed, compiled, and converted into arbitrary numbers referred to as ‘activity counts’ by Actical software. Activity counts were summed and recorded at intervals of 15 sec. Activity data are represented as activity counts per hr. Indirect calorimetry was measured in calorimetry chambers measuring 0.52 × 0.52 × 0.41 m. Respiratory exchange ratio, heat, and flow of air through the chambers were measured using an open-circuit Oxymax System (Software, Version 5.0, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). Cats were food restricted overnight before indirect calorimetry and acclimated to the calorimetry chambers for at least 4 hr, after which time measurements were collected for 2 hr. Data from these 2 hr were extrapolated to obtain 24 hr daily energy expenditure values.

Adipose tissue sample collection and handling

Adipose tissue biopsies were collected at wk 12 of each period for RNA isolation and sequencing. After withholding food for at least 12 hr, cats were sedated with butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg), atropine (0.04 mg/kg) and medetomadine (0.02 mg/kg; intramuscular). Approximately 1 g of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue was collected, immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until further analyses.

RNA extraction

Total cellular RNA was isolated from adipose samples using the Trizol reagent as suggested by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA concentration was determined using a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA integrity was confirmed using a 1.2% denaturing agarose gel.

Construction of RNA-seq libraries

Construction of libraries and sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq2000 was performed at the W. M. Keck Center for Comparative and Functional Genomics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (Urbana, IL). RNA-seq libraries were constructed using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina San Diego, CA). Briefly, mRNA was selected from one microgram of high quality total RNA. First-strand synthesis was synthesized with a random hexamer and SuperScript II (Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Double-stranded DNA was blunt-ended, 3′-end A-tailed and ligated to indexed adaptors. The adaptor-ligated double-stranded cDNA was amplified by PCR for 10 cycles with the Kapa HiFi polymerase (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA) to reduce the likeliness of multiple identical reads due to preferential amplification. The final libraries were quantified using a Qubit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and the average size was determined on an Agilent bioanalyzer DNA7500 DNAchip (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE), diluted to 10 nM and the indexed libraries were pooled in equimolar concentrations. The pooled libraries were further quantified by qPCR on an ABI 7900, which resulted in high accuracy and a maximization of cluster numbers in the flowcell.

Illumina sequencing

The multiplexed libraries were loaded onto three lanes of an 8-lane flowcell for cluster formation and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000. One of the lanes was loaded with a PhiX Control library that provides a balanced genome for calculation of matrix, phasing and pre-phasing, which are essential for accurate base calling. The libraries were sequenced from one end of the molecules to a total read length of 100 nt. The raw .bcl files were converted into de-multiplexed fastq files with Casava 1.8.2 (Illumina, CA).

RNA-sequence alignment and statistical analysis

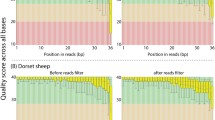

Raw FASTQ data were quality-trimmed from the 5′ and 3′ ends using the program Seqtk (http://github.com/lh3/seqtk), using a minimal PHRED quality score of 20 and a minimal length of 25. Sequences were then aligned using TopHat v. 2.0.6 [31] and Bowtie 2.0.4 [32]. The reference genome annotation and sequence index were from Felis_catus_6.2 from Ensembl (http://useast.ensembl.org/Felis_catus/Info/Annotation/#assembly). We used the GTF gene model file provided by The Sanger Centre for splice junctions and read counts (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/users/searle/cat). Each file was sorted using novosort (http://www.novocraft.com/wiki/tiki-index.php?page=Novosort;structure=Novocraft+Technologies;page_ref_id=91) prior to read counting. Raw read counts were tabulated from each sample from the generated BAM alignments at the gene level using htseq-count, from HTSeq v0.5.4p1 (http://www-huber.embl.de/users/anders/HTSeq/doc/index.html).

The raw read counts were input into R 2.15.1 [33] for data pre-processing and statistical analysis using packages from Bioconductor [34] as indicated below. Genes without 1 count per million mapped reads in at least one of the samples were filtered out due to unreliable data in any sample. Those genes that passed this filter were analyzed using edgeR 2.6.10 [35]. The raw count values were used in a negative bionomial statistical model that accounts for the total library size for each sample and an extra normalization factor [36] for any biases due to changes in highly expressed genes [37]. For sample clustering and heatmaps, comparable expression values were generated from the read counts using the voom transformation from limma 3.12.1 [38]. Gene symbols, descriptions, and Gene Ontology terms for the Ensembl gene models were downloaded from Ensembl Genes 70, Felis_catus_6.2. All raw sequence data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) archives (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession #GSE46431 (GSM1130067-GSM1130086).

Results and discussion

Obesity is a common health problem in the domestic cat population. Common therapeutic options include dietary intervention, mainly by energy restriction, and increased physical activity. Although these strategies are logical, in practice, they are not often successful. A better understanding of the molecular changes that occur in metabolically active tissues, including adipose tissue, may increase our understanding of feline metabolism, identifying methods for promoting weight maintenance. Photoperiod has been shown to alter the metabolism and BW of many seasonal animals, but has not been well studied in cats. Because their breeding habits and physical activity levels are altered by season [12–14], we believe that studying photoperiod may identify novel strategies to improve weight maintenance in pet cats. In this study, our objective was to use RNA-seq to identify genes and biological pathways differentially expressed in adipose tissue of lean adult cats housed in SD vs. LD conditions. So that we could study the effects of photoperiod using a crossover design and without the bias of BW change between periods, cats were fed to maintain BW throughout the entire study. Although the effects of photoperiod in our study may differ from cats fed ad libitum, we believed this study design was most appropriate to identify photoperiod-induced changes without the bias of BW gain.

As described above and presented by Kappen et al. [14], cats were fed to maintain BW (4.6 kg) and body condition score throughout the study. Cats were composed of approximately 16% fat mass, 82% lean mass, and 2% bone mass, values that were not altered by photoperiod. To maintain BW, however, SD-housed cats required less (P < 0.0001) energy than LD-housed cats (187 vs. 196 kcal/d). Similarly, SD-housed cats had reduced (P = 0.008) physical activity as assessed by accelerometers (3129 vs. 3770 activity counts/hr) and reduced (P < 0.05) resting metabolic rate as assessed by indirect calorimetry (8.4 vs. 9.0 kcal/hr) [14]. Because photoperiodic history may impact response to day length, the history of the cats studied herein is important. For most of their lives, the cats used in this study have been housed in an indoor animal facility without exposure to natural light and under a 16 hr light: 8 hr dark photoperiod. This light cycle has been used in our facility for many years due to practical reasons. It allows us to perform a variety of study designs and allows the collection of samples (blood, fecal, or urine), feeding, weighing, etc. early in the morning or into the evening when the lights are on in the facility (6 am to 10 pm). Because the current study was performed as a crossover design and 12-wk periods were used, previous history likely did not impact the gene expression results presented here, but it cannot be ruled out completely.

Because commercial DNA microarrays are not currently available for cats, we used RNA-seq to analyze global gene expression profiles of adipose tissue in this study. A total of 578 million sequences (28.9 million/sample) were generated by Illumina sequencing. Using a raw p value of P < 0.005, 170 mRNA transcripts were differentially expressed between SD- and LD-housed cats. Of the 170 transcripts highlighted, 89 annotated transcripts were up-regulated by SD, while 24 annotated transcripts were down-regulated by SD. Another 57 un-annotated transcripts (name and function not known) were also different between groups. Annotated, non-redundant genes were then classified into functional classes using SOURCE (http://smd.princeton.edu) [39] and NCBI resources (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Adipose tissue is complex and contains many different cell types, including adipocytes, preadipocytes, immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts. Our data are derived from adipose tissue biopsies, so gene expression differences cannot be attributed to different cellular fractions or types, but represents changes in gene expression of whole adipose tissue. Nonetheless, according to gene ontology classification, expression of genes in several broad functional categories, including protein processing and ubiquitination, nucleotide metabolism, transcription, cell growth and differentiation, cell development and structure, cell signaling, immune function, metabolism, and ion transport and binding, were altered by photoperiod (Figure 1). Altogether, these gene expression changes suggest that SD housing may promote adipogenesis, minimize inflammation and oxidative stress, and alter lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in adipose tissue of cats. Rather than feeding cats to maintain BW, as was done in this study, ad libitum access to food and the allowance of weight gain would probably be needed to test this physiologic response effectively.

Based on the gene expression changes observed in this study, namely the up-regulation of myostatin (MSTN), frizzled-related protein (FRZB), several kelch-like proteins (KLHL23, 33, 34, and 38; KBTBD12), and several genes involved with protein ubiquitination, adipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation appeared to be more abundantly expressed in SD- vs. LD-housed cats (Tables 1 and 2). Melatonin has been shown to promote differentiation of 3T3-L1 fibroblasts in vitro[40], but its effects on adipose metabolism of cats in vivo have not been described. Adipogenesis is the process by which mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into adipocytes. One of the most important regulators of this process is the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Constitutive activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in preadipocytes inhibits differentiation by preventing the induction of C/EBPα and PPARγ [41, 42]. Conversely, inactivation of this pathway releases the brake on adipogenesis [43–45]. Therefore, increased expression of FRZB, which is known to be a Wnt antagonist [46, 47], suggested increased adipogenesis in SD-housed cats. Because cats were not allowed to gain BW or body composition in this study and because excess adipose tissue was not available to measure markers of adipogenesis (e.g., Pref-1 only expressed in pre-adipocytes; FABP4 only expressed in mature adipocytes), it is unknown whether the process was actually up-regulated. MSTN, the expression of which was also increased in SD-housed cats, is a member of the TGF-β superfamily and is most commonly known as an important regulator of skeletal muscle development. While high levels of MSTN are detected in skeletal muscle, low levels are also detected in other tissues, including adipose tissue [48]. Although mixed results have been demonstrated in vitro[49, 50], MSTN overexpression in adipose tissue in vivo results in an increased number of small immature adipocytes, increased energy expenditure, and resistance to obesity [51]. MSTN appears to regulate preadipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism in adipose tissue via ERK1/2 [52].

LIM domain 7 (LMO7), tripartite motif containing 55 (TRIM55), ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component n-recognin 3 (UBR3), WW domain containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (WWP1), cullin 3 (CUL3), and ubiquitin specific peptidase 28 (USP28), all of which are involved in protein ubiquitination and the ubiquitin cycle, were up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 1). The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway has a well-established role in a number of physiological and pathological processes and is known to be important in cellular differentiation [53–55]. Proteasome activity has been shown to be at its highest level during the early stages of differentiation in human adipose-derived stem cells [56] and reduced as stem cells become differentiated. KLHL23, KLHL33, KLHL34, KLHL38, and kelch repeat and BTB (POZ) domain containing 12 (KBTBD12) were up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 1). Kelch family proteins contain two conserved domains, a BTB domain, and a kelch repeat domain. The kelch repeat domain is involved in organization of the cytoskeleton via interaction with actin and intermediate filaments, whereas the BTB domain has multiple cellular roles, including recruitment to E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes [57, 58]. Kelch-related actin-binding protein has previously been shown to be expressed in adipose tissue, specifically in the adipose-derived stroma-vascular fraction [59], and is transiently induced early during adipocyte differentiation. This induction precedes the expression of the transcription factors, PPARγ and C/EBPα, and other adipocyte-specific markers including adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein. Although both kelch-like proteins and FRZB are known to affect the induction of C/EBPα and PPARγ, those genes were not differentially expressed between SD- and LD-housed cats in the present study. The lack of response may have been due to the food-restricted feeding protocol in our study. If fed ad libitum, it is likely that increased energy intake and adipose expansion would have occurred resulting in increased PPARγ and C/EBPα expression.

Keratins (KRT5, 14, 25, 74, and 85) and keratin-associated proteins (KRTAP8-1; KRTAP11-1), all related to cell development, were up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 2). Keratin filaments are abundant in keratinocytes in the cornified layer of the epidermis - cells that have undergone keratinization. Cytokeratins are expressed by mesenchymal stem cells of human adipose tissue [60]. Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) is also expressed by mesenchymal stem cells in adipose tissue and functions in a paracrine fashion to stimulate epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation [61, 62]. KGF mRNA is present in the stromal–vascular fraction of human adipose tissue [63], and its expression is up-regulated in early-life programmed rat model of increased visceral adiposity [64]. KGF is produced by rat mature adipocytes and preadipocytes as well as 3T3-L1 cells [65]. Importantly, Zhang et al. [65] demonstrated that KGF stimulates preadipocyte proliferation, but not differentiation, via an autocrine mechanism. Although the expression of several cytokeratins was influenced by photoperiod in this study, KGF expression was not altered. The role of keratin and keratin associated protein in adipose tissue is unclear and warrants further investigation.

The expression of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and CCL5, plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI1), CD1e molecule, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD80, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4 (TIMD4), and TIM1 were lower in SD-vs. LD-housed cats (Table 3), suggesting reduced macrophage number and inflammation in adipose tissue. CCL2, also called monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), is believed to be an important initiator of adipose inflammation because it is important in attracting inflammatory cells into white adipose tissue. CCL2 expression is positively correlated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue, with overexpression being associated with obesity and insulin resistance [66–68]. CCL5 functions similarly by recruiting macrophages into adipose tissue and activating nuclear factor-kappa-B (NFκB) signaling [69, 70]. PAI1 is a protease inhibitor that facilitates blood clotting. It is also thought to contribute to the development of insulin resistance and obesity, however, with its expression being induced by increased circulating free fatty acids [71–73]. Because adipose tissue macrophages express high levels of PAI1 [74], these data are in agreement with that of CCL2 and CCL5, and suggests increased macrophage infiltration in LD-housed cats in the current study. TIM1, TIMD4, and CD80, all expressed by macrophages, are involved in regulating T-cell proliferation and activation. ICAM-1 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and is overexpressed during high-fat diet feeding or under conditions of inflammation [75, 76]. Although common pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNFα; IFNγ; IL6) were not differentially expressed in our study, collectively, our data suggest a lower macrophage number or activity and a decreased level of inflammation in adipose tissue of SD-housed cats.

Inflammation and oxidative stress not only alter energy homeostasis and host metabolism, but contribute to insulin resistance as well. Fasting blood glucose concentrations were not different between groups in our study [14]. Blood insulin was not measured. Photoperiod has the potential to manipulate these processes because melatonin is a powerful free radical scavenger [77] and regulator of antioxidant enzymes [78]. Recently, melatonin has also been shown to modify inflammatory proteins such as TNFα and ICAM1 [79] and improve insulin sensitivity in obese rats [80]. Ankyrin 1 (ANK1), ANK3, ankyrin repeat and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) box containing 4 (ASB4), ASB14, and ASB15, were up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 2). ASB proteins are involved in cellular differentiation and appear to regulate components of the insulin signaling pathway. ASB4, specifically, is down-regulated in the hypothalamus of rats during fasting and with obesity [81, 82]. ASB4 appears to influence insulin signaling by inhibiting c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) activity [83], but further research is necessary to clarify its role in adipose tissue. Several genes associated with calcium transport, including ATPase, Ca++ transporting, plasma membrane 2 (ATP2B2), calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha 2/delta subunit 1 (CACNA2D1), phospholamban (PLN), solute carrier family 8 (sodium/calcium exchanger), member 3 (SLC8A3), and ryanodine receptor 3 (RYR3), were also up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 4). Intracellular Ca2+ plays an important role in adipocyte lipid metabolism and triglyceride storage, modulating energy storage in this tissue. Although these changes have been associated with improved insulin sensitivity, response to glucose or insulin dose was not tested in this study. Uncoupling proteins (UCP) are most widely known for their ability to separate oxidative phosphorylation from ATP synthesis, resulting in thermogenesis, but appear to have other functions as well. UCP3, expressed in muscle and adipose tissues, was up-regulated in SD-housed cats and has been shown to be up-regulated by PPARγ [84], increases mitochondrial Ca++ uptake [85], and is thought to limit the production of reactive oxygen species [86].

In the current study, several genes associated with lipid and carbohydrate metabolism were altered due to photoperiod, but not with clear implications on feline health. Expression of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD), adiponutrin (ADPN), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), oxidized low density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1), and apolipoprotein L domain containing 1 (APOLD1), all involved in lipid and cholesterol metabolism, were down-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 3). Epilepsy, progressive myoclonus type 2A, Lafora disease (laforin) (EPM2A), protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 3A, and amylo-alpha-1,6-glucosidase, 4-alpha-glucanotransferase (AGL), all involved in glycogen metabolism, were up-regulated in SD-housed cats (Table 4).

Glycogen storage is much lower in adipose tissue compared to skeletal muscle and liver, but is present and believed to yield precursors for glycerol formation and lipid deposition [87, 88]. SCD is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids [89], and appears to change with BW. Reduced adiposity of the SCD-knock out mouse has been attributed to reduced lipid biosynthesis and increased lipid oxidation [90], while increased SCD in obese subjects seems to favor lipid storage [91–93]. ADPN is highly expressed in adipose tissue and appears to play a role in lipogenesis, being positively correlated with lipogenic enzymes and negatively correlated with uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1) [94]. G6PDH is a metabolic cytosolic enzyme involved in the pentose phosphate pathway, which provides NADPH for tissues actively engaged in the biosynthesis of fatty acids and/or isoprenoids. G6PDH is highly expressed in adipocytes of obese animal models and is involved with adipocytokine expression, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance [95, 96]. LDLR and OLR1 internalize LDL and oxidized LDL, respectively. LDL is the primary carrier of cholesterol in the bloodstream, with LDLR playing an important role in regulating blood cholesterol concentrations. OLR1 is one of a group of scavenger receptors, which are transmembrane proteins involved in several cellular functions, including adhesion and elimination of apoptotic cells and modified lipoproteins such as oxidized LDL. Oxidized LDL internalization leads to macrophage infiltration and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [97]. OLR1 expression has been shown to be regulated by adiponectin and PPARγ [98, 99], but also associated with insulin resistance [99]. Collectively, these gene expression differences suggest a difference in adipose tissue metabolism between SD- and LD-housed cats, with SD-housed cats having an increased level of glycogen synthesis, but lower level of lipogenesis in the fasted state.

Because this study has several limitations, data interpretation requires caution. One limitation was that our study only includes gene expression data. Because our adipose tissue biopsies were quite small, each sample was used entirely for RNA isolation and sequencing. Thus, we were not able to perform histological or any other analysis on those samples to compare adipocyte size, number, or responsiveness. Second, circulating melatonin was not measured in this study because a validated method for feline melatonin measurement is not currently available. Third, gene expression profiles were based on the entire adipose biopsy sample rather than a specific cell type. Lastly, cats were fed to maintain BW to limit changes to photoperiod. Therefore, the differences observed here may be different than cats allowed to adjust BW according to season that is known to occur in many seasonal animals. Despite the limitations provided above, this study provides a novel dataset of the adipose tissue transcriptome changes in response to photoperiod in healthy cats.

Conclusions

Photoperiod is known to cause physiological changes in seasonal animals and has been shown to affect energy intake, energy expenditure, and voluntary physical activity levels in cats. The molecular mechanisms by which these changes occur and the possible role that adipose tissue plays, however, are unknown. Our mRNA abundance data suggests that short day housing promotes adipogenesis, minimizes inflammation and oxidative stress, and alters lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in adipose tissue of cats, even when fed to maintain BW. Future research is needed to confirm these results in cats fed ad libitum and allowed to adjust food intake and BW according to photoperiod. Research designed to link gene expression of specific adipose cell types to pertinent physiologic outcomes is also justified.

Availability of supporting data

The dataset supporting the results of this article is available in the Gene Expression Omnibus repository at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) archives (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession #GSE46431 (GSM1130067-GSM1130086).

References

Hastings MH: Neuroendocrine rhythms. Pharmacol Therapeutics. 1991, 50: 35-71.

Bartness TJ, Powers JB, Hastings MH, Bittman EL, Goldman BD: The timed infusion paradigm for melatonin delivery: what has it taught us about the melatonin signal its reception and the photoperiodic control of seasonal responses?. J Pineal Res. 1993, 15: 161-190.

Dark J, Zucker I: Gonadal and photoperiodic control of seasonal body weight changes in male voles. Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 1984, 247: R84-R88.

Wade N, Bartness TJ: Effects of photoperiod and gonadectomy on food intake, body weight, and body composition in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 1984, 246: R26-R30.

Bartness TJ, Wade GN: Photoperiodic control of body weight and energy metabolism in Syrian hamsters (mesocricetus auratus): role of pineal gland, melatonin, gonads, and diet. Endocrinology. 1984, 114: 492-498.

Gower BA, Nagy TR, Stetson MH: Effect of photoperiod, testosterone, and estradiol on body mass, bifid claw size, and pelage color in collared lemmings (Dicrostonyx groenlandicus). Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1994, 93: 459-470.

Kriegsfeld LJ, Nelson RJ: Gonadal and photoperiodic influences on body mass regulation in adult male and female prairie voles. Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 1996, 270: R1013-R1018.

Nieminen P, Mustonen AM, Asikainen J, Hyvärinen H: Seasonal weight regulation of the raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides): interactions between melatonin, leptin, ghrelin, and growth hormone. J Biol Rhythms. 2002, 17: 155-163.

Dawson AB: Early estrus in the cat following increased illumination. Endocrinology. 1941, 28: 907-910.

Leyva H, Madley T, Stabenfeldt GH: Effect of light manipulation on ovarian activity and melatonin and prolactin secretion in the domestic cat. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1989, 39: 125-133.

Michel C: Induction of oestrus in cats by photoperiodic manipulations and social stimuli. Lab Anim. 1993, 27: 278-280.

Schmidt K, Nakanishi N, Izawa M, Okamura M, Watanabe S, Tanaka S, Doi T: The reproductive tactics and activity patterns of solitary carnivores: the Iriomote cat. J Ethol. 2009, 27: 165-174.

Bermingham EN, Weidgraaf K, Hekman M, Roy NC, Tavendale MH, Thomas DG: Seasonal and age effects on energy requirements in domestic short-hair cats (Felis catus) in a temperate environment. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2013, 97: 522-530.

Kappen KL, Garner LM, Kerr KR, Swanson KS: Effects of photoperiod on weight maintenance in adult neutered male cats. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). in press; 2013.

Reimers E, Ringberg T, Sorumgaard R: Body composition of Svalbard reindeer. Can J Zool. 1982, 60: 1812-1821.

Bocquier F, Bonnet M, Faulconnier Y, Guerre-Millo M, Martin P, Chilliard Y: Effects of photoperiod and feeding level on perirenal adipose tissue metabolic activity and leptin synthesis in the sheep. Reprod Nutr Dev. 1998, 38: 489-498.

Bernabucci U, Basiricò L, Lacetera N, Morera P, Ronchi B, Accorsi PA, Seren E, Nardone A: Photoperiod affects gene expression of leptin and leptin receptors in adipose tissue from lactating dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89: 4678-4686.

Klingenspor M, Dickopp A, Heldmaier G, Klaus S: Short photoperiod reduces leptin gene expression in brown and white adipose tissue of Djungarian hamsters. FEBS Lett. 1996, 399: 290-294.

Frühbeck G: A heliocentric view of leptin. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001, 60: 301-318.

Demas GE, Bowers RR, Bartness TJ, Gettys TW: Photoperiodic regulation of gene expression in brown and white adipose tissue of Siberian hamsters (Phodopus sungorus). Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 2002, 282: R114-R121.

El-Haschimi K, Lehnert H: Leptin resistance - or why leptin fails to work in obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003, 111: 2-7.

Bartness TJ, Hamilton JM, Wade GN, Goldman BD: Regional differences in fat pad responses to short days in Siberian hamsters. Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 1989, 257: R1533-R1540.

Faulconnier Y, Bonnet M, Bocquier F, Leroux C, Chilliard Y: Effects of photoperiod and feeding level on adipose tissue and muscle lipoprotein lipase activity and mRNA level in dry non-pregnant sheep. Brit J Nutr. 2001, 85: 299-306.

Powell CS, Blaylock ML, Wang R, Hunter HL, Johanning GL, Nagy TR: Effects of energy expenditure and Ucp1 on photoperiod-induced weight gain in collard lemmings. Obes Res. 2002, 10: 541-550.

Belsito KR, Vester BM, Keel T, Graves TK, Swanson KS: Impact of ovariohysterectomy and food intake on body composition, physical activity, and adipose gene expression in cats. J Anim Sci. 2009, 87: 594-602.

Vester BM, Sutter SM, Keel TL, Graves TK, Swanson KS: Ovariohysterectomy alters body composition and adipose and skeletal muscle gene expression in cats fed a high-protein or moderate-protein diet. Animal. 2009, 3: 1287-1298.

Vester BM, Liu KJ, Keel TL, Graves TK, Swanson KS, Graves TK, Swanson KS: In utero and postnatal exposure to a high-protein or high-carbohydrate diet leads to differences in adipose tissue mRNA expression and blood metabolites in kittens. Brit J Nutr. 2009, 102: 1136-1144.

Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M: RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009, 10: 57-63.

Li XJ, Yang H, Li GX, Zhang GH, Cheng J, Guan H, Yang GS: Transcriptome profile analysis of porcine adipose tissue by high-throughput sequencing. Anim Genet. 2012, 43: 144-152.

Laflamme DP: Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a clinical tool. Feline Pract. 1997, 25: 13-18.

Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL: TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25: 1105-1111.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL: Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012, 9: 357-359.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, URL; 2012. http://www.R-project.org/. ISBN 3-900051-07-0

Gentleman R, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J: Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004, 5: R80.

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK: edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26: 139-140.

Robinson MD, Oshlack A: A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11: R25.

McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK: Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40: 4288-4297.

Smyth GK: Limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor: Springer. Edited by: Gentleman R, Carey V, Dudoit S, Irizarry R, Huber W. New York: Springer; 2005:397-420.

Diehn M, Sherlock G, Binkley G, Jin H, Matese JC, Hernandez-Boussard T, Rees CA, Cherry JM, Botstein D, Brown PO, Alizadeh AA: SOURCE: a unified genomic resource of functional annotations, ontologies, and gene expression data. Nucleic Acid Res. 2003, 31: 219-223.

González A, Alvarez-García V, Martínez-Campa C, Alonso-González C, Cos S: Melatonin promotes differentiation of 3 T3-L1 fibroblasts. J Pineal Res. 2012, 52: 12-20.

Farmer SR: Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006, 4: 263-273.

Rosen ED, MacDougald OA: Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 7: 885-896.

Christodoulides C, Laudes M, Cawthorn WP, Schinner S, Soos M, O'Rahilly S, Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A: The Wnt antagonist Dickkopf-1 and its receptors are coordinately regulated during early human adipogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2006, 119: 2613-2620.

Cawthorn WP, Heyd F, Hegyi K, Sethi JK: Tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibits adipogenesis via a beta-catenin/TCF4(TCF7L2)-dependent pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14: 1361-1373.

Prestwich TC, Macdougald OA: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in adipogenesis and metabolism. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007, 19: 612-617.

Jones SE, Jomary C: Secreted frizzled-related proteins: searching for relationships and patterns. Bioessays. 2002, 24: 811-820.

Kawano Y, Kypta R: Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003, 116: 2627-2634.

McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ: Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-beta superfamily member. Nature. 1997, 387: 83-90.

Kim HS, Liang L, Dean RG, Hausman DB, Hartzell DL, Baile CA: Inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation by myostatin treatment in 3T3-L1 cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001, 281: 902-906.

Artaza JN, Bhasin S, Magee TR, Reisz-Porszasz S, Shen R, Groome NP, Meerasahib MF, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF: Myostatin inhibits myogenesis and promotes adipogenesis in C3H 10 T(1/2) mesenchymal multipotent cells. Endocrinology. 2005, 146: 3547-3557.

Feldman BJ, Streeper RS, Farese RV, Yamamoto KR: Myostatin modulates adipogenesis to generate adipocytes with favorable metabolic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103: 15675-15680.

Li F, Yang H, Duan Y, Yin Y: Myostatin regulates preadipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism of adipocyte via ERK1/2. Cell Biol Int. 2011, 35: 1141-1146.

Ichihara A, Tanaka K: Roles of proteasomes in cell growth. Mol Biol Rep. 1995, 21: 49-52.

Mugita N, Honda Y, Nakamura H, Fujiwara T, Tanaka K, Omura S, Shimbara N, Ogawa M, Saya H, Nakao M: The involvement of proteasome in myogenic differentiation of murine myocytes and human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Int J Mol Med. 1999, 3: 127-137.

Guo W, Shang F, Liu Q, Urim L, Zhang M, Taylor A: Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway function is required for lens cell proliferation and differentiation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006, 47: 2569-2575.

Sakamoto K, Sato Y, Sei M, Ewis AA, Nakahori Y: Proteasome activity correlates with male BMI and contributes to the differentiation of adipocyte in hADSC. Endocrine. 2010, 37: 274-279.

Stogios PJ, Privé GG: The BACK domain in BTB-kelch proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004, 29: 634-637.

Wu YL, Gong Z: A novel zebrafish kelchlike gene klhl and its human ortholog KLHL display conserved expression patterns in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Gene. 2004, 338: 75-83.

Zhao L, Gregoire F, Sul HS: Transient induction of ENC-1, a Kelch-related actin-binding protein, is required for adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 16845-16850.

Martinez-Conesa EM, Espel E, Reina M, Casaroli-Marano RP: Characterization of ocular surface epithelial and progenitor cell markers in human adipose stromal cells derived from lipoaspirates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012, 53: 513-520.

Rubin JS, Bottaro DP, Chedid M, Miki T, Ron D, Cheon H-G, Taylor WG, Fortney E, Sakata H, Finch PW, LaRochelle WJ: Keratinocyte growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995, 19: 399-411.

Finch PW, Rubin JS: Keratinocyte growth factor/fibroblast growth factor 7, a homeostatic factor with therapeutic potential for epithelial protection and repair. Adv Cancer Res. 2004, 91: 69-136.

Gabrielsson BG, Johansson JM, Jennische E, Jernås M, Itoh Y, Peltonen M, Olbers T, Lönn L, Lönroth H, Sjöström L, Carlsson B, Carlsson LM, Lönn M: Depot-specific expression of fibroblast growth factors in human adipose tissue. Obes Res. 2002, 10: 608-616.

Guan H, Arany E, van Beek JP, Chamson-Reig A, Thyssen S, Hill DJ, Yang K: Adipose tissue gene expression profiling reveals distinct molecular pathways that define visceral adiposity in offspring of maternal protein-restricted rats. Am J Physiol. 2005, 288: E663-E673.

Zhang T, Guan H, Yang K: Keratinocyte growth factor promotes preadipocyte proliferation via an autocrine mechanism. J Cell Biochem. 2010, 109: 737-746.

Kamei N, Tobe K, Suzuki R, Ohsugi M, Watanabe T, Kubota N, Ohtsuka-Kowatari N, Kumagai K, Sakamoto K, Kobayashi M, Yamauchi T, Ueki K, Oishi Y, Nishimura S, Manabe I, Hashimoto H, Ohnishi Y, Ogata H, Tokuyama K, Tsunoda M, Ide T, Murakami K, Nagai R, Kadowaki T: Overexpression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in adipose tissues causes macrophage recruitment and insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 26602-26614.

Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Miyachi H, Maeda S, Egashira K, Kasuga M: MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116: 1494-1505.

Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF: Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117: 902-909.

Keophiphath M, Rouault C, Divoux A, Clément K, Lacasa D: CCL5 promotes macrophage recruitment and survival in human adipose tissue. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010, 30: 39-45.

Kauts M-L, Pihelgas S, Orro K, Neuman T, Piirsoo A: CCL5/CCR1 axis regulates multipotency of human adipose tissue derived stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. 2013, 10: 166-178.

Schäfer K, Fujisawa K, Konstantinides S, Loskutoff DJ: Disruption of the plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 gene reduces the adiposity and improves the metabolic profile of genetically obese and diabetic ob/ob mice. FASEB J. 2001, 15: 1840-1842.

De Taeye BM, Novitskaya T, Gleaves L, Covington JW, Vaughan DE: Bone marrow plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 influences the development of obesity. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 32796-32805.

Esterson YB, Kishore P, Koppaka S, Li W, Zhang K, Tonelli J, Lee DE, Kehlenbrink S, Lawrence S, Crandall J, Barzilai N, Hawkins M: Fatty-acid induced production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by adipose macrophages is greater in middle-aged versus younger adult participants. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012, 67: 1321-1328.

Kishore P, Li W, Tonelli J, Lee DE, Koppaka S, Zhang K, Lin Y, Kehlenbrink S, Scherer PE, Hawkins M: Adipocyte-derived factors potentiate nutrient-induced production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by macrophages. Sci Transl Med. 2010, 2: 20ra15.

Dustin ML, Rothlein R, Bhan AK, Dinarello CA, Springer TA: Induction by IL 1 and interferon-gamma: tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function of a natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1). J Immunol. 1986, 137: 245-254.

Brake DK, Smith EO, Mersmann H, Smith CW, Robker RL: ICAM-1 expression in adipose tissue: effects of diet-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol. 2006, 291: C1232-C1239.

Poeggeler B, Saarela S, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Chen LD, Manchester LC, Barlow-Walden LR: Melatonin - a highly potent endogenous radical scavenger and electron donor: new aspects of the oxidation chemistry of this indole accessed in vitro. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994, 738: 419-420.

Rodriguez C, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Antolín I, Herrera F, Martín V, Reiter RJ: Regulation of anti-oxidant enzymes: a significant role for melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2004, 36: 1-9.

Yip H-K, Chang Y-C, Wallace CG, Chang LT, Tsai TH, Chen YL, Chang HW, Leu S, Zhen YY, Tsai CY, Yeh KH, Sun CK, Yen CH: Melatonin treatment improves adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for acute lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Pineal Res. 2013, 54: 207-221.

Zanuto R, Siqueira-Filho MA, Caperuto LC, Bacurau RF, Hirata E, Peliciari-Garcia RA, Do Amaral FG, Marçal AC, Ribeiro LM, Camporez JP, Carpinelli AR, Bordin S, Cipolla-Neto J, Carvalho CR: Melatonin improves insulin sensitivity independently of weight loss in old obese rats. J Pineal Res. 2013, 55: 156-165.

Li J-Y, Kuick R, Thompson RC, Misek DE, Lai YM, Liu YQ, Chai BX, Hanash SM, Gantz I: Arcuate nucleus transcriptome profiling identifies ankyrin repeat and SOCS box-containing protein 4 as a gene regulated by fasting in central nervous system feeding circuits. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005, 17: 394-404.

Li J-Y, Chai B, Zhang W, Wu X, Zhang C, Fritze D, Xia Z, Patterson C, Mulholland MW: Akyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) colocalizes with insulin receptor substrate 4 (IRS4) in the hypothalamic neurons and mediates IRS4 degradation. BMC Neurosci. 2011, 12: 95.

Li J-Y, Chai B-X, Zhang W, Liu Y-Q, Ammori JB, Mulholland MW, Liu Y-Q, Ammori JB, Mulholland MW: Akyrin repeat and SOCS box containing protein 4 (Asb-4) interacts with GPS1 (CSN1) and inhibits c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity. Cell Signalling. 2007, 19: 1185-1192.

Matsuda J, Hosoda K, Itoh H, Son C, Doi K, Hanaoka I, Inoue G, Nishimura H, Yoshimasa Y, Yamori Y, Odaka H, Nakao K: Increased adipose expression of the uncoupling protein-3 gene by thiazolidinediones in Wistar fatty rats and in cultured adipocytes. Diabetes. 1998, 47: 1809-1814.

Trenker M, Malli R, Fertschai I, Levak-Frank S, Graier WF: Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3 are fundamental for mitochondrial Ca2+ uniport. Nat Cell Biol. 2007, 9: 445-452.

Bouillaud F: UCP2, not a physiologically relevant uncoupler but a glucose sparing switch impacting ROS production and glucose sensing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009, 1787: 377-383.

Eichner RD: Adipose-tissue glycogen-synthesis. Int J Biochem. 1984, 16: 257-261.

Jurczak MJ, Danos AM, Rehrmann VR, Allison MB, Greenberg CC, Brady MJ: Transgenic overexpression of protein targeting to glycogen markedly increases adipocyte glycogen storage in mice. Am J Physiol. 2007, 292: E952-E963.

Cohen P, Ntambi JM, Friedman JM: Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2003, 3: 271-280.

Sjögren P, Sierra-Johnson J, Gertow K, Rosell M, Vessby B, de Faire U, Hamsten A, Hellenius ML, Fisher RM: Fatty acid desaturases in human adipose tissue: relationships between gene expression, desaturation indexes and insulin resistance. Diabetologia. 2008, 51: 328-335.

Jones BH, Maher MA, Banz WJ, Zemel MB, Whelan J, Smith PJ, Moustaïd N: Adipose tissue stearoyl-CoA desaturase mRNA is increased by obesity and decreased by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Am J Physiol. 1996, 271: E44-E49.

Dobrzyn A, Ntambi JM: The role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase in body weight regulation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004, 14: 77-81.

Alligier M, Meugnier E, Debard C, Lambert-Porcheron S, Chanseaume E, Sothier M, Loizon E, Hssain AA, Brozek J, Scoazec JY, Morio B, Vidal H, Laville M: Subcutaneous adipose tissue remodeling during the initial phase of weight gain induced by overfeeding in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012, 97: E183-E192.

Oliver P, Caimari A, Diaz-Rua R, Palou A: Cold exposure down-regulates adiponutrin/PNPLA3 mRNA expression and affects its nutritional regulation in adipose tissues of lean and obese Zucker rats. Brit J Nutr. 2012, 107: 1283-1295.

Park J, Rho HK, Kim KH, Choe SS, Lee YS, Kim JB: Overexpression of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is associated with lipid dysregulation and insulin resistance in obesity. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25: 5146-5157.

Park J, Choe SS, Choi AH, Kim KH, Yoon MJ, Suganami T, Ogawa Y, Kim JB: Increase in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase in adipocytes stimulates oxidative stress and inflammatory signals. Diabetes. 2006, 55: 2939-2949.

Martin-Fuentes P, Civeira F, Recalde D, García-Otín AL, Jarauta E, Marzo I, Cenarro A: Individual variation of scavenger receptor expression in human macrophages with oxidized low-density lipoprotein is associated with a differential inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2007, 179: 3242-3248.

Chui PC, Guan H-P, Lehrke M, Lazar M: PPARγ regulates adipocyte cholesterol metabolism via oxidized LDL receptor 1. J Clin Invest. 2005, 115: 2244-2256.

Rasouli N, Yao-Borengasser A, Varma V, Spencer HJ, McGehee RE, Peterson CA, Mehta JL, Kern PA: Association of scavenger receptors in adipose tissue with insulin resistance in nondiabetic humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009, 29: 1328-1335.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by Hatch Project #ILLU-538-384. We thank Alvaro Hernandez, Christopher Fields, and Jenny Drnevich for assistance with RNA sequencing, gene annotation, and statistical analyses, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KSS designed the research experiment; KLK conducted the animal experiment and collected adipose tissue; AM performed laboratory analysis; and AM, ACD, and KSS wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mori, A., Kappen, K.L., Dilger, A.C. et al. Effect of photoperiod on the feline adipose transcriptome as assessed by RNA sequencing. BMC Vet Res 10, 146 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-146

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-10-146