Abstract

Background

Many recent papers have documented the phytochemical and pharmacological bases for the use of palms (Arecaceae) in ethnomedicine. Early publications were based almost entirely on interviews that solicited local knowledge. More recently, ethnobotanically guided searches for new medicinal plants have proven more successful than random sampling for identifying plants that contain biodynamic ingredients. However, limited laboratory time and the high cost of clinical trials make it difficult to test all potential medicinal plants in the search for new drug candidates. The purpose of this study was to summarize and analyze previous studies on the medicinal uses of American palms in order to narrow down the search for new palm-derived medicines.

Methods

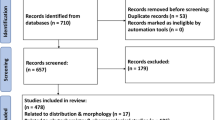

Relevant literature was surveyed and data was extracted and organized into medicinal use categories. We focused on more recent literature than that considered in a review published 25 years ago. We included phytochemical and pharmacological research that explored the importance of American palms in ethnomedicine.

Results

Of 730 species of American palms, we found evidence that 106 species had known medicinal uses, ranging from treatments for diabetes and leishmaniasis to prostatic hyperplasia. Thus, the number of American palm species with known uses had increased from 48 to 106 over the last quarter of a century. Furthermore, the pharmacological bases for many of the effects are now understood.

Conclusions

Palms are important in American ethnomedicine. Some, like Serenoa repens and Roystonea regia, are the sources of drugs that have been approved for medicinal uses. In contrast, recent ethnopharmacological studies suggested that many of the reported uses of several other palms do not appear to have a strong physiological basis. This study has provided a useful assessment of the ethnobotanical and pharmacological data available on palms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Palms (Arecaceae) are common throughout the American tropics. They abound in hot, wet regions on the continents and associated archipelagos, particularly in areas covered by tropical rainforests [1, 2]. Most of the 730 species of American palms [3] are used, particularly in rural areas, for food, shelter, fuel, medicine, and many other purposes [4]. For instance, in Ecuador, uses have been recorded for 111 of the 123 palm species present in that country [5]. This study extends from Plotkin and Balick's (1984) seminal paper that reviewed the medicinal uses of American palms. Plotkin and Balick deplored that the biodynamic and organic ingredients of palms were nearly unknown; but, during the quarter century since that publication, there has been increasing interest in palms as a source of active compounds. In recent years, pharmacological studies have become more numerous than ethnobotanical reports on medicinal palms. This may help bridge the gap between ethnobotanical data and clinical testing for the beneficial effects of palm products on human health.

The primary aim of this bibliographical survey was to compare existing ethnobotanical and pharmacological studies on the medicinal uses of palms. Gathering this large quantity of information may facilitate future search for new palm-derived medicines. A preliminary version of our database was presented at a palm symposium in Lima, Peru, in 2007 [6]. For this paper, we expanded the database with information from new and additional references and we present a full analysis of the data.

Methods

We collected literature reports concerning the use of American palms in ethnomedicine and organized them according to palm species and use categories. We updated the nomenclature of palm names, including the authors' names, according to the World Checklist of Palms [7]. Thus, when the name of a palm in a publication was considered a synonym of an accepted name, we used the accepted name. Plotkin and Balick (1984) listed the medicinal uses of palms under each species name. Instead, we presented the information according to categories of health disorders, in accordance with the Economic Botany Data Collection Standard prepared for the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences [8]. However, we departed from this standard by subdividing infections/infestations into the following categories: Fever, Bacterial, Fungal, Parasitic, and Viral infections. We added another category for Social Uses, including healing rituals, smoking materials, intoxicants, and religious uses that often influence human health (See additional file 1 for the categorized data derived from our literature searches). The latter categories are not included in the medicinal categories in Cook (1995).

Palms provide several nutritious food items. Therefore, they may be important in combating nutrient deficiency, a serious public health problem, particularly in developing countries. The nutrient compositions of palm fruits and palm-cabbage have been widely investigated and reported in the literature; therefore, these are not reviewed here.

Publications that described the use of palms in ethnomedicine covered most American countries where palms are found (Fig. 1). In addition, they investigated many, but far from all, ethnic groups in tropical America. The papers reviewed here cover both indigenous and non-indigenous societies.

Our bibliographic searches employed several databases, including PubMed, Embase, and RedLightGreen. In addition, we conducted dedicated searches with the search engines of The State and University Libraries of Aarhus. We also accessed many publications in the reprint collections accumulated by one of the authors (HB) over many years of palm and ethnobotanical research. We performed special searches at the Amazonian Library and in the Instituto de Investigaciones en la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) in Iquitos, Peru.

Results and Discussion

Medicinal palms

We found reports of medicinal uses for 106 American palm species (see Additional File 1). The most commonly used were: Cocos nucifera, for 19 different medicinal use categories, Oenocarpus bataua, for 14 categories; and Euterpe precatoria, for 14 categories (Fig. 2). Cocos nucifera is commonly cultivated throughout the Americas and was most likely introduced from other countries; in contrast, O. bataua and E. precatoria are native to the tropical rainforests of the Amazon basin and adjacent regions. The next most commonly used species was Attalea speciosa (13 categories). Phoenix dactylifera, Euterpe oleracea, Attalea phalerata, Phytelephas macrocarpa, Bactris gasipaes, Acrocomia aculeata, and Socratea exorrhiza were employed in 9-12 different medicinal use categories. Among American indigenous peoples, the best-known ethnomedicinal palms are the native palms, O. bataua, S. exorrhiza, E. precatoria, and a species with unknown origin, C. nucifera [1]. C. nucifera is widely cultivated throughout the tropical areas of the world. Thus, medicinal use of C. nucifera is the most widespread of the palms in the Americas (Fig. 2).

The fruit of the palm is most commonly used for medicinal purposes; the fruit is used in 56 species, the oil is used in 19 species, the mesocarp in 16 species, and the endosperm in 11 species. Other parts of the palms that are used include roots (27 spp.), leaves (22 spp.), palm hearts (19 spp.), stems (17 spp.), and flowers (9 spp.). Often, several species in the same genus are used medicinally (Fig. 3). For example, the genus Attalea has 11 different species with medicinal uses; the genera Astrocaryum, Bactris, and Syagrus each have 10 medicinal species; and the genus Geonoma has seven medicinal species; all the other genera have 1-5 species that are used medicinally. As expected, species from the same genus often have similar uses [9] but there are exceptions to this rule; O. bataua prevents fever, but Oenocarpus bacaba can be harmful to a person recovering from intermittent fever [10, 11].

Obviously, most medicinal uses of palms are beneficial; but, like many other drugs, inappropriate use may be harmful. For instance, a beverage made of O. bataua fruit is said to quickly cause a "horrible death" when mixed with liver of tapir [12]. The prevalence of medicinal palm use is notable; for example, the roots of E. precatoria are used medicinally almost everywhere it grows [10, 13–19].

Categories of health disorders treated with palms

In a general ethnomedicinal study of indigenous communities in Mexico, the most frequent ailments treated with medicinal plants were gastrointestinal disorders, dermatological diseases, and respiratory disorders [20]. These categories were also confirmed by other authors [21–23] that studied ethnomedicines in the indigenous societies of the Americas. In this paper, we used a different classification of diseases [8] (Fig. 4); our data related mainly to indigenous, but also to some non-indigenous peoples; and we looked only at health conditions treated with medicines from a single plant family. Among the diseases treated by palms, digestive system disorders were frequent, but pain ailments and skin tissue disorders were even more frequent. The preponderance of pain, injuries, and muscular-skeletal system disorders that could be treated with palm medicines may have reflected the epidemiological characteristics of the indigenous peoples in the region. Some indigenous peoples live in a traditional way, where hunting and gathering play a considerable role in subsistence. Hence, injuries and muscular-skeletal system disorders may be directly connected to everyday hunting activities. Palm-derived remedies may provide emergency treatments, as they commonly grow around villages and are easily accessible. Emergency medicines derived from palms, particularly those with styptic properties, like those derived from A. speciosa, are commonly used by the Apinayé and Guajajara Indians of northeastern Brazil [12]. Among the Warao and Arawak of Guyana, E. oleracea is considered a useful hemostatic medicine when a person is injured deep in the forest [24]; the sap of Euterpe edulis also possesses hemostatic properties [25].

Circulatory system disorders are among the major health problems in Western civilization; however, these seem not to be important among peoples that use American ethnomedicines derived from palms. Similarly, there are almost no reports of neurological system disorders that are common among ageing Western societies.

Indirect impact of palm on human health

Palm medicines also have an indirect influence human health. Beetle larvae that live in the decaying stems of Astrocaryum chambira, Wettinia maynensis [26], A. phalerata, and O. bataua are collected and used in medicines to cure severe chest pains [27–29]. A fungus that causes chromoblastomycosis has been found in the shell of A. speciosa, which may explain the prevalence of this disease among farm workers in the Amazon region of Maranhao in Brazil [30]. Problems with Triatominae infested palms are common in many places [31–41]. Most Rhodonius sp. (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) are associated with palm trees; they transmit Trypanosoma cruzi, the organism responsible for Chagas disease throughout the American tropics [42].

Traditional medicines of American peoples are also used to treat some folk illnesses like susto - bad spirit. Folk illnesses form part of the broader indigenous world-view, and there are no direct equivalents in modern medicine nomenclature. From the medical point of view, folk illnesses are not diseases sensu stricto, but clusters of loosely bound syndromes. Consequently, in the category of Social Uses for palm medicines, we included uses connected to healing rituals and folk illnesses.

Local versus pharmacological knowledge

As mentioned above, previous knowledge about the ethnomedicinal uses of American palms was based primarily on local knowledge and ethnobotanical studies [25]; in contrast, many recent papers have investigated the phytochemical and pharmacological bases for ethnomedicinal treatments. We compared local rationale and pharmacological evidence in a number of cases where both kinds of evidence existed.

There are many, often conflicting, reports about the medicinal properties of A. speciosa (babassu). Mesocarp flour from its fruit is used in Brazil to treat pain, constipation, obesity, leukemia, rheumatism, tumors, and ulcerations (references in Additional File 1). It has also been shown to have anti-inflammatory [43] or pro-inflammatory [44] properties, depending on the inflammation model and the time or route of treatment. These reports, together with the fact that it is used to treat venous disease, suggest that it could be a good candidate for the development of new medicines [45]. However, when tested, extracts of its leaves, flowers, and endocarp did not show pharmacological activity [46]. This may suggest that the uses are based on physiological effects of the mesocarp, which may have properties not found in other parts of babassu palm.

Interestingly, sap from the stem of E. oleracea (açai) is used as a hemostatic agent among Matowai, Arawak, and Warao peoples; however, pharmacological studies indicated that the fruit stone extract of E. oleracea had a vasodilator effect [47]. The fruit of E. oleracea also holds promise for use in modern medicine as an alternative oral contrasting agent for MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) studies of the gastrointestinal system [48].

The traditional claim that roots of E. precatoria have anti-inflammatory activity appears to have been verified, although the mechanism that underlies the effect remains unknown [19].

The roots of E. precatoria and the fruits of O. bataua were traditionally and are presently used to treat malaria in Peru [[15], Rengifo 2007, and Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarollo 2007 personal communication]. Although Deharo et al. (2001) [49] did not include these species in their pharmacological tests of anti-malarial activity, other studies showed a moderate antiplasmodial activity in extracts of E. precatoria roots [50].

In ethnobotanical studies, the fruit extracts of Astrocaryum vulgare and A. speciosa have been reported to be useful for the treatment of skin diseases. However, when they were screened for anti-tyrosinase activity, the effect was poor [51].

Hypoglycemic compounds have been found in the roots of A. aculeata in many studies; this coincides well with its traditional use as a treatment for diabetes among indigenous peoples in Mexico [52–54].

Coconut (C. nucifera) oil was shown to have antiseptic effects and is used as an efficient, safe skin moisturizer [55]. This suggested that its traditional use as a lotion in many parts of America is well founded. Its selective antibacterial effects [56] also make it useful for topical applications in wound healing. Other studies have suggested that extracts from C. nucifera husk fibers could be useful in the treatment of leishmaniasis [57, 58]. In traditional Mexican medicine, C. nucifera has been used to treat trichomoniasis, dysentery, and enteropathogens. These uses are consistent with its antimicrobial effects. Moreover, recent pharmacological studies have demonstrated that extracts of C. nucifera could be used as an alternative method to treat drug resistant enteric infections [59, 60]. In vivo assays demonstrated that C. nucifera extract had low toxicity, and that it did not induce dermic or ocular reactions [57]. Thus, considering its potent antioxidant activity and low toxicity, husk fiber extracts of C. nucifera have potential in the treatment of oral diseases [61]. Furthermore, its aqueous extract may be a source of new drugs with anti-neoplastic and anti-multidrug resistance activities [62]. It is of great interest for cancer therapy to identify new compounds that are able to overcome resistance mechanisms and lead to tumor cell death.

Seeds of Aiphanes aculeata were traditionally used for treatment of cancer by people from the Peruvian Amazon region (Rengifo, personal communication, 2007). Lee et al. (2001) [63] isolated Aiphanol and some other compounds that may have chemopreventive properties, but they have not been pharmacologically tested for their effects on cancer.

Increasing attention has focused on the use of phytotherapeutic agents to treat prostate disorders, ranging from benign prostatic hyperplasia to prostate cancer. The best described phytotherapeutic agent for prostate disorders was from Serenoa repens (saw palmetto) [[64–68], among others]. Several studies have reported no side effects of saw palmetto treatments [69], and a dietary supplement with S. repens may be effective in controlling prostate cancer tumorigenesis [70]. The extract of S. repens was as effective as the tested pharmaceuticals in the relief of urinary symptoms [71, 72]. The roots of Roystonea regia are used as a traditional medicine in Eastern Cuba to cure impotence [73]. Currently, R. regia fruit lipid extracts are being tested in the Cuban National Center for Scientific Research, and preliminary results suggest that they appear to provide a promising treatment for prostatic hyperplasia [74–82].

Conclusions

Palms have been used for the treatment of various human ailments throughout the Americas by many societies and in many regions. Local knowledge about the medicinal uses of palms is extensive, and recent ethnopharmacological studies have confirmed the effectiveness of many of the treatments; however, some uses appear not to have a physiological basis and others have not been investigated.

Ethnopharmacological research may improve the therapeutic use of traditional medicine in regions where these palms were originally used, and this information may also be important for the design of new drugs. Further analysis of the pharmacological activities of palm extracts may enable the design of less expensive therapies. Natural products are currently the leading source of new biologically active compounds. The ingestion of palm products with medicinal properties represents a concrete alternative treatment in many areas with limited access to modern medicine. Pharmacological analyses have previously focused on the antibiotic effects of palm medicines, but these medicines have also shown potential in the fight against prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes, leishmaniasis, and other diseases.

Abbreviations

- own obs:

-

own observation

- BACTER:

-

bacterial infections

- BLOOD:

-

blood system disorders

- CIRCUL:

-

circulatory system disorders

- DIGEST:

-

digestive system disorders

- ENDOCR:

-

endocrine system disorders

- FUNGAL:

-

fungal infections

- GENITO:

-

genitourinary system disorders

- ILLDEF:

-

ill-defined symptoms

- INFLAM:

-

inflammations

- INJUR:

-

injuries

- MENTAL:

-

mental disorders

- MUSCUL:

-

muscular-skeletal system disorders

- NEUROL:

-

neurological system disorders

- NEOPL:

-

neoplasms

- NUTRIT:

-

nutritional disorders

- ODONT:

-

odontological disorders

- PARASI:

-

parasitic infections

- POISON:

-

poisonings

- PREGN:

-

pregnancy/birth/puerperium disorders

- RESPIR:

-

respiratory system disorders

- SENSOR:

-

sensory system disorders

- SKIN:

-

skin/subcutaneous cell tissue disorders

- SOCIAL:

-

social uses

- VIRAL:

-

viral infections.

References

Henderson A, Galeano G, Bernal R: Field guide to the palms of the Americas. 1995, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

Vormisto J, Svenning JC, Hall P, Balslev H: Diversity and dominance in palm (Arecaceae) communities in terra firme forest in the western Amazon basin. J Ecol. 2004, 92: 577-588. 10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00904.x.

Dransfield J, Uhl NW, Asmussen CB, Baker WJ, Harley MM, Lewis CE: Genera Palmarum - the evolution and classification of palms. 2008, Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens

Balslev H, Barfod A: Ecuadorean palms - an overview. Opera Bot Societ Bot Lundensi. 1987, 92: 17-35.

de la Torre L, Navarrete H, Muriel MP, Macía MJ, Balslev H, (Eds): Enciclopedia de las Plantas Útiles del Ecuador. 2008, Quito & Aarhus: Herbario QCA & Herbario AAU

Sosnowska J, Balslev H: American palms used for medicine, in the ethnobotanical and pharmacological publications. Rev Peru Boil. 2008, 15: 143-146.

Govaerts R, Dransfield J: World Checklist of Palms. 2005, Kew: The Board of Trustees of Royal Botanic Gardens

Cook F: Economic Botany Data Collection Standard prepared for the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (TDWG). 1995, Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens

Bletter N: A quantitative synthesis of the medicinal ethnobotany ot the Malinké of Mali and the Asháninka of Peru, with a new theoretical framework. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007, 3: 36-10.1186/1746-4269-3-36.

Bourdy G, DeWalt SJ, Michel LR, Deharo E, Muñoz V, Balderrama L, Quenevo C, Gimnez A: Medicinal plants uses of Tacana, an Amazonian Bolivian ethnic group. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70: 87-109. 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00158-0.

Wallace AR: Palm trees of the Amazon and their uses. 1971, Kansas: Coronado Press

Balick MJ: Systematics and Economic Botany of the Oenocarpus -- Jessenia (Palmae) Complex. Adv Econ Bot. 1986, 3: 17-21.

Campos MT, Ehringhaus C: Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazonia. Econ Bot. 2003, 57: 324-344. 10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0324:PVAITE]2.0.CO;2.

Desmarchelier C, Repetto M, Coussio J, Llesuy S, Ciccia G: Total reactive antioxidant potential (TRAP) and total antioxidant reactivity (TAR) of medicinal plants used in southwest Amazonia (Bolivia and Peru). Internat J Pharmacol. 1997, 35: 288-296. 10.1076/phbi.35.4.288.13303.

Kahn F, Granville J: Palms in Forest Ecosystems of Amazonia. Ecol Stud. 1992, 95: 155-159.

Lescure JP, Balslev H, Alarcón R: Plantas Utiles de la Amazonia Ecuatoriana. 1987, Quito: ORSTOM

Paniagua-Zambrana NY: Diversidad, densidad, distribución y uso de las palmas en la region del Madidi, noreste del departamento de La Paz (Bolivia). Ecol Boliv. 2005, 40: 265-280.

de la Torre L, Alarcón SD, Kvist LP, Lecaro JS: Usos medicinales de las plantas. Enciclopedia de las plantas útiles del Ecuador. Edited by: de laTorre L, Navarrete H, Muriel MP, Macía MJ, Balslev H. 2008, Herbario QCA & Herbario AAU. Quito & Aarhus, 105-114.

Deharo E, Baelmans R, Gimenez A, Quenevo C, Bourdy G: In vitro immunomodulatory activity of plants used by Tacana ethnic group in Bolivia. Phytomedicine. 2004, 11: 516-522. 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.07.007.

Heinrich M: Ethnobotany and its Role in Drug Development. Phytother Res. 2000, 14: 479-488. 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<479::AID-PTR958>3.0.CO;2-2.

Martinez GJ: "Vienen buscando la vida" ("llotaique nachaalataxac"): Las trayectorias terapéuticas de los tobas del Río Bermejito (Chaco). Los caminos terapéuticos y los rastos de la diversidad. Tomo 1. 2007, Idoyaga MA: CAEA - IUNA, 401-424.

Tene V, Malagón O, Finzi PV, Vidari G, Armijos C, Zaragoza T: An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in Loja and Zamora-Chinchipe, Ecuador. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111: 63-81. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.032.

Vandebroek I, Thomas E, Sanca S, Van Damme P, Van Puyvelde L, De Kimpe N: Comparison of health conditions treated with traditional and biomedical health care in a Quechua community in rural Bolivia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008, 4: 1-12. 10.1186/1746-4269-4-1.

Andel T: Non-timber forest products of the North-West District of Guyana. A field guide. Part I. Tropenbos-Guyana Series 8B. PhD thesis. 2000, Utrecht University

Plotkin MJ, Balick MJ: Medicinal uses of South American palms. J Ethnoptarmacol. 1984, 10: 157-179. 10.1016/0378-8741(84)90001-1.

Cerón CE, Ayala CM: Ethnobotanica de los Huaorani de Quehueiri-Ono-Napo-Ecuador. 1998, Quito: Abya-Yala, 178-187.

Barfod A, Balslev H: The use of palms by the Cayapas and Coaiqueres on the coastal plain of Ecuador. Princeps. 1988, 32: 29-42.

DeWalt SJ, Bourdy G, Chavez de Michel LR, Quenevo C: Ethnobotany of the Tacana: Quantitive Inventories of Two Permanent Plots of Northwestern Bolivia. Econ Bot. 1999, 53: 237-260. 10.1007/BF02866635.

Macía MJ: Multiplicity in palm uses by the Huaorani of Amazonian Ecuador. Bot J Lin Soc. 2004, 144: 149-159. 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2003.00248.x.

Marques SG, Silva CMP, Saldanha PC, Rezende MA, Vicente VA, Queiroz-Telles F, Costa JML: Isolation of Fonsecaea pedrosi from the shell of the babassu coconut (Orbignya phalerata Martius) in the Amazon Region of Maranhão Brazil. Jap J Med Mycol. 2006, 47: 305-311. 10.3314/jjmm.47.305.

Miles MA, Arias JR, Souza AA: Chagas' disease in the Amazon basin: V. Periurban palms as habitats of Rhodnius robustus and Rhodnius pictipes - triatomine vectors of Chagas' disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1983, 78: 391-398. 10.1590/S0074-02761983000400002.

D'Alessandro A, Barreto P, Saravia N, Barreto M: Epidemiology of Trypanosoma cruzi in the oriental plains of Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984, 33: 1084-1095.

Diotaiuti L, Dias JC: Ocorrencia e biologia do Rhodnius neglectus Lent, 1954 em macaubeiras da periferia de Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Mém Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1984, 79: 293-301.

Bar ME, Wisnievsky-Colli C: Triatoma sordida Stål 1859 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae: Triatominae) in palms of northeastern Argentina. Mém Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001, 96: 895-899.

Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Palma ART, Manezes MNA, Leite RN, Cuba CAC: Sampling Rhodonius neglectus in Mauritia flexuosa palm trees: a field study in the Brazilian savanna. Med Veter Entomol. 2003, 17: 347-349. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00448.x.

Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Durante MA, Ramalho ED, Palma AR, Romaña CA, Cuba CAC: Spatial distribution of Triatominae populations (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Mauritia flexuosa palm trees in Federal District of Brazil. Rev Socied Bras Med Trop. 2004, 37: 241-247.

Sarquis O, Borges-Pereira J, Mac Cord JR, Gomes TF, Cabello PH, Lima MM: Epidemiology of Chagas Disease in Jaguaruana, Ceará, Brazil. I. Presence of triatomines and index of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in four localities of rural area. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004, 99: 263-270.

Sanchez-Martin MJ, Feliciangeli MD, Campbell-Lendrum D, Davies CR: Could the Chagas disease elimination programme in Venezuela be compromised by reinvasion of houses by sylvatic Rhodnius prolixus bug populations?. Trop Med Int Health. 2006, 11: 1585-1593. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01717.x.

Arévalo A, Carranza JC, Guhl F, Clavijo JA, Vallejo GA: Comparision of the life cycles of Rhodnius colombiensis Moreno, Jurberg and Galvão, 1999 and R. prolixus Stal, 1872 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae, Triatominae) under laboratory conditions. Biomedica. 2007, 27: 119-129.

Feliciangeli MD, Sanchez-Martin M, Marrero R, Davies C, Dujardin JP: Morphometric evidence for a possible role of Rhodnius prolixus from palm trees in house re-infestation in the State of Barinas (Venezuela). Acta Tropica. 2007, 101: 169-177. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.12.010.

Samudio F, Ortega-Barría E, Saldaña A, Calzada J: Predominance of Trypanosoma cruzi among Panamanian sylvatic isolates. Acta Tropica. 2007, 101: 178-181. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.12.008.

Abad-Franch F, Palomaque FS, Aguilar HM, Miles MA: Field ecology of sylvatic Rhodnius populations (Heteroptera, Triatominae): risk factor for palm tree infestation in western Ecuador. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2005, 10: 1258-1266. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01511.x.

Silva BP, Parente JP: An anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory polysaccharide from Orbigna phalerata. Fitoterapia. 2001, 72: 887-893. 10.1016/S0367-326X(01)00338-0.

Azevedo APS, Ferreira SCP, Chagas AP, Barroqueiro ESB, Guerra RNM, Nascimento FRF: Effect of babassu mesocarp treatment on paw edema and inflammatory mediators' liberation. Rev Ciên Saúde. 2003, 5: 21-28.

Azevedo APS, Farias JC, Costa GC, Ferreira SCP, Filho WCA, Sousa PRA, Pinheiro MT, Maciel MCG, Silva LA, Lopes AS, Barroqueiro ESB, Borges MOR, Guerra RNM, Nascimento FRF: Anti-thrombotic effect of chronic oral treatment with Orbignya phalerata Mart. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 111: 155-159. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.11.005.

Silva CG, Herdeiro RS, Mathias CJ, Panek AD, Silveira CS, Rodrigues VP, Rennó MN, Falcão DQ, Cerqueira DM, Minto ABM, Nogueira FLP, Quaresma CH, Silva JFM, Menezes FS, Eleutherio ECA: Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Brazilian plants. Pharmacol Res. 2005, 52: 229-233. 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.03.008.

Rocha APM, Carvalho LCRM, Sousa MAV, Madeira SVF, Sousa PJC, Tano T, Schini-Kerth VB, Resende AC, Soares de Moura R: Endothelium-dependent vasodilator effect of Euterpe oleracea Mart. (Açaí) extracts in mesenteric vascular bed of the rat. Vascul Pharmacol. 2007, 46: 97-104. 10.1016/j.vph.2006.08.411.

Córdova-Fraga T, de Araujo DB, Sanchez TA, Elias J, Carneiro AA, Brandt-Oliveira R, Sosa M, Baffa O: Euterpe oleracea (Acai) as an alternative oral contrast agent in MRI of the gastrointestinal system: preliminary results. Magn Reson Imag. 2004, 22: 389-393. 10.1016/j.mri.2004.01.018.

Deharo E, Bourdy G, Quenevo C, Muñoz V, Ruiz G, Sauvain M: A search for natural bioactive compounds in Bolivia through a multidisciplinary approach. Part V. Evaluation of the antimalarial activity of plants used by Tacana Indians. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 77: 91-98. 10.1016/S0378-8741(01)00270-7.

Jensen JF, Kvist LP, Christensen SB: An antiplasmodial lignan from Euterpe precatoria. J Nat Prod. 2002, 65: 1915-1917. 10.1021/np020264u.

Baurin N, Arnoult E, Scior T, Do QT, Bernard P: Preliminary screening of some tropical plants for anti-tyrosinase activity. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 82: 155-158. 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00174-5.

Pérez GS, Pérez GRM, Pérez GC, Zavala SMA, Vargas SR: Coyolosa, a new hypoglycemic from Acrocomia mexicana. Pharm Acta Helvetiae. 1997, 72: 105-111. 10.1016/S0031-6865(96)00019-2.

Haines AH: Evidence on the structure of coyolosa. Synthesis of 6,6'-ether linked hexoses. Tetrah Let. 2004, 45: 835-837. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2003.11.033.

Andrade-Cetto A, Heinrich M: Mexican plants with hypoglycaemic effect used in the treatment of diabetes. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 99: 325-348. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.019.

Agero AL, Verallo-Rowell VM: A randomized double-blind controlled trial comparing extra virgin coconut oil with mineral oil as a moisturizer for mild to moderate xerosis. Dermatitis. 2004, 15: 109-116.

Esquenazi D, Wigg MD, Miranda MMFS, Rodrigues HM, Tostes JBF, Rozental S, Silva AJR, Alviano CS: Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of polyphenolics from Cocos nucifera Linn. (Palmae) husk fiber extract. Res Microbiol. 2002, 153: 647-652. 10.1016/S0923-2508(02)01377-3.

Alviano DS, Rodrigues KF, Leitão SG, Rodrigues ML, Matheus ML, Fernández PD, Antoniolli AR, Alviano CS: Antinociceptive and free radical scavenging activities of Cocos nucifera L. (Palmae) husk fiber aqueous extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92: 269-273. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.013.

Mendonca-Filho RR, Rodrigues IA, Alviano DS, Santos ALS, Soares RMA, Alviano CS, Lopes AHCS, Rosa MS: Leishmanicidal activity of polyphenolic-rich extract from husk fiber of Cocos nucifera Linn. (Palmae). Res Microbiol. 2004, 155: 136-143. 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.12.001.

Alanís AD, Calzada F, Cervantes JA, Torres J, Ceballos GM: Antibacterial properties of some plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100: 153-157. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.022.

Calzada F, Yépez-Mula L, Tapia-Contreras A: Effect of Mexican medicinal plant used to treat trichomoniasis on Trichomonas vaginalis trophozoites. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 113: 248-251. 10.1016/j.jep.2007.06.001.

Alviano WS, Alviano DS, Diniz CG, Antoniolli AR, Alviano CS, Farias LM, Carvalho MAR, Souza MMG, Bolognese AM: In vitro antioxidant potential of medicinal plant extracts and their activities against oral bacteria based on Brazilian folk medicine. Arch Oral Biol. 2008, 53: 545-552. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.12.001.

Koschek PR, Alviano DS, Alviano CS, Gattas CR: The husk fiber of Cocos nucifera L. (Palmae) is a source of anti-neoplastic activity. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007, 40: 1339-1343. 10.1590/S0100-879X2006005000153.

Lee D, Cuendet M, Vigo JS, Graham JG, Cabieses F, Fong HHS, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD: A Novel Cyclooxygenase-Inhibitory Stilbenolignan from the Seeds of Aiphanes aculeata. Org Let. 2001, 14: 2169-2171. 10.1021/ol015985j.

Belostotskaia LI, Nikitchenko IV, Gomon ON, Chaĭka LA, Bondar VV, Dziuba VN: Effect of biologically active substances of animal and plant origin on prooxidant-antioxidant balance in rats with experimental prostatic hyperplasia. Eksp Klin Farmakol. 2006, 69: 66-68.

Ulbricht C, Basch E, Bent S, Boon H, Corrado M, Foppa I, Hashmi S, Hammerness P, Kingsbury E, Smith M, Szapary P, Vora M, Weissner W: Evidence-based systematic review of saw palmetto by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. J Soc Integ Oncology. 2006, 4: 170-186. 10.2310/7200.2006.016.

Hizli F, Uygur MC: A prospective study of the efficacy of Serenoa repens, tamsulosin, and Serenoa repens plus tamsulosin treatment for patients with benign prostate hyperplasia. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007, 39: 879-886. 10.1007/s11255-006-9106-5.

Hostanska K, Suter A, Melzer J, Saller R: Evaluation of cell death caused by an ethanolic extract of serenoa repentis fructus (Prostatan) on human carcinoma cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2007, 27: 873-882.

Lopatkin N, Sivkov A, Schläfke S, Funk P, Medvedev A, Engelmann U: Efficacy and safety of a combination of Sabal and Urtica extract in lower urinary tract symptoms -- long-term follow-up of a placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007, 39: 1137-1146. 10.1007/s11255-006-9173-7.

Beckert BW, Concannon MJ, Henry SL, Smith DS, Puckett CL: The effect of herbal medicines on platelet function: an in vivo experiment and review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007, 120: 2044-2050. 10.1097/01.prs.0000295972.18570.0b.

Wadsworth TL, Worstell TR, Greenberg NM, Roselli CE: Effects of dietary saw palmetto on the prostate of transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model (TRAMP). Prostate. 2007, 67: 661-673. 10.1002/pros.20552.

Comhaire F, Mahmoud A: Preventing diseases of the prostate in the elderly using hormones and nutriceuticals. Aging Male. 2004, 7: 155-169. 10.1080/13685530412331284722.

Gong EM, Gerber GS: Saw palmetto and benign prostatic hyperplasia. AJCM. 2004, 32: 331-338. 10.1142/S0192415X04001989.

Cano JH, Volpato G: Herbal mixtures in the traditional medicine of eastern Cuba. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 90: 293-316. 10.1016/j.jep.2003.10.012.

Arruzazabala ML, Carbajal D, Mas R, Molina V, Rodriguez E, Gonzalez V: Preventive effects of D-004, a lipid extract from Cuban royal palm (Roystonea regia) fruits, on testosterone-induced prostate hyperplasia in intact and castrated rodents. Drug Exp Clin Res. 2004, 30: 227-233.

Arruzazabala ML, Mas R, Carbajal D, Molina V: Effect of D-004, a lipid extract from the Cuban royal palm fruit, on in vitro and in vivo effects mediated by alpha-adrenoceptors in rats. Drugs in R & D. 2005, 6: 281-289.

Arruzazabala ML, Más R, Molina V, Noa M, Carbajal D, Mendoza N: Effect of D-004, a lipid extract from the Cuban royal palm fruit, on atypical prostate hyperplasia induced by phenylephrine in rats. Drugs in R & D. 2006, 7: 233-241.

Arruzazabala ML, Molina V, Más R, Carbajal D: Effects of D-004, a lipid extract from the royal palm (Roystonea regia) fruits, tamsulosin and their combined use on urodynamic changes induced with phenylephrine in rats. Arzneimittelforschung. 2008, 58: 81-85.

Carbajal D, Molina V, Mas R, Arruzazabala ML: Therapeutic effect of D-004, a lipid extract from Roystonea regia fruits, on prostate hyperplasia induced in rats. Drug Exp Clin Res. 2005, 31: 193-197.

Gamez R, Mas R, Noa M, Menendez R, Garcia H, Rodriguez Y, Felipe E, Goicochea E: Oral acute and subchronic toxicity of D-004, a lipid extract from Roysonea regia fruits, in rats. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 2005, 31: 101-108.

Noa M, Arruzazabala ML, Carbajal D, Más R, Molina V: Effect of D-004, a lipid extract from Cuban royal palm fruit, on histological changes of prostate hyperplasia induced with testosterone in rats. Int J Tissue React. 2005, 27: 203-211.

Menéndez R, Más R, Pérez Y, González RM: In vitro effect of D-004, a lipid extract of the ground fruits of the Cuban royal palm (Roystonea regia), on rat microsomal lipid peroxidation. Phytoterap Res. 2007, 21: 89-95. 10.1002/ptr.2012.

Gutiérrez A, Gámez R, Mas R, Noa M, Pardo B, Marrero G, Pérez Y, González R, Curveco D, Garcia H: Oral subchronic toxicity of a lipid extract from Roystonea regia fruits in mice. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2008, 31: 217-228. 10.1080/01480540701873152.

UMSA, CIPTA, IRD, FONAMA, EIA: Tacana - Conozcan nuestros arboles, nuestras hierbas. 1999, La Paz: Conselo lndîgeno de los Pueblos Tacana (CIPTA) - Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD)

Usher G: Dictionary of plants used by man. 1974, New York: Hafner Press

Pereira H: Pequena contribução para um diccionairio das plantas uteis do estado de São Paulo. 1929, São Paulo: Typographia Brasil de Rothschild e Co

García Barriga H: Flora medicinal de Colombia. Botánica Médica. Tomo I. 1974, Bogotá: Tercer Mundo Editores, 138-147.

Schultes RE: Plantae Austro-Americanae VII. Harvard Univ Bot Mus Leafl. 1951, 15: 29-78.

Perez Arbelaez E: Plantas Utiles de Colombia. 1978, Bogota: Litografía Arco

Balick MJ: Native Neotropical Palms: a Resource of Global Interest. New crops for food and Industry. Edited by: Wickens GE, Haq N, Day P. 1989, London: Chapman and Hall, 323-332.

Schultes RE, Raffauf RF: The Healing Forest: Medicinal and Toxic plants of the Northwest Amazonia. 1990, Oregon: Dioscorides Press, 348-359.

Bennett BC, Baker MA, Gómez Andrade P: Ethnobotany of the Shuar of eastern Ecuador. Adv Econ Bot. 2002, 14: 1-299.

Díaz MIA: Plantas medicinales, vademécum popular comunidades del Samiria y Marañón. 2003, Iquitos: CETA, 18-69.

Fanshawe D: Forest Products of British Guyana, Part II. 1950, British Guyana: Forest Dept. British Guiana, [Series: Forestry Bulletin 2 (New Series)]

Ayensu ES: Medicinal Plants of West Indies. 1981, Michigan: Reference Publications, Inc

Grimwood BE, Ashman F, Dendy DAV, Jarman CG, Little ECS: Coconut palm products. Their processing in developing countries. 1975, Rome: FAO, 165-167. [Series: FAO Agricultural Development Papers volume 99]

Braga R: Plantas do nodeste, especialmente de Ceará. 1960, Fortaleza: Imprensa Oficinal

Pio Correa M: Diccionario das plantas uteis do Brasil e das exoticas cultivadas. 1926, Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional

LeCointe P: Arvores e Plantas Uteis. 1934, Belém: Livraria Classica

Leonti M, Sticher O, Heinrich M: Antiquity of medicinal plant usage in two Macro-Mayan ethnic groups (Mexico). J Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88: 119-124. 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00188-0.

Matheus ME, Fernandes SBO, Silveira CS, Rodrigues VP, Menezes FS, Fernandes PD: Inhibitory effects of Euterpe oleracea Mart. on nitric oxide production and iNOS expression. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107: 291-296. 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.010.

Johnson T: CRC ethnobotany desk reference. 1999, Washington: CRC Press LLC

Boom BM: Ethnobotany of the Chácobo Indians, Beni, Bolivia. Adv Econ Bot. 1987, 4: 1-68.

Nascimento FRF, Barroqueiro ESB, Azevedo APS, Lopes AS, Ferreira SCP, Silva LA, Maciel MCG, Rodriguez D, Guerra RNM: Macrophage activation induced by Orbigna phalerata Mart. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 103: 53-58. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.045.

Prance GT, Silva MF: Arvores de Manaus. 1975, Manaus, Amazonas: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia

Moraes RM, Borshsenius F, Blicher-Mathiesen U: Notes on the biology and uses of the motacú palm (Attalea phalerata, Arecaceae) from Bolivia. Econ Bot. 1996, 4: 423-428.

Balslev H, Rios M, Quezada G, Nantipa B: Palmas útiles en la Cordillera de los Huacamayos. 1997, Quito: PROBONA, 1-57. [Series: Colección Manuales de Aprovechamento Sustenable de Bosque, vol 1]

Andel T: Non-timber forest products of the North-West District of Guyana. A field guide. Part II. Tropenbos-Guyana Series 8B. PhD thesis. 2000, Utrecht University

Balick MJ: Economic botany of the Guahibo, I. Palmae. Econ Bot. 1980, 33: 361-376. 10.1007/BF02858332.

Duke JA, Vasquez R: Amazonian ethnobotanical dictionary. 1994, Boca Raton: CRS Press

Pittier H: Manual de las plantas usuales de Venezuela. 1926, Caracas: Litografia del Comercio

Perez Arbelaez E: Plantas Utiles de Colombia. 1956, Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra

Balick MJ: Jessenia and Oenocarpus: neotropical oil palms worthy of domestication. 1988, Rome: FAO

García Barriga H: Flora medicinal de Colombia. Botánica Médica. Tomo I. 1974, Bogota: Tercer Mundo Editores, 138-147. Garcia Barriga 1992

Quero H: Las palmas silvesres de la penísula de Yucatan. 1992, México: Publicaciones Especiales del Instituto de Biología, 10:

Pérez GS, Pérez GRM, Pérez GC, Zavala SMA, Vargas SR: Coyolosa, a new hypoglycemic from Acrocomia mexicana. Pharm Acta Helvetiae. 1997, 72: 105-111. 10.1016/S0031-6865(96)00019-2.

Mejía CK: Utilization of palms in eleven mestizo villages of the Peruvian Amazon (Ucayali river, department of Loreto). 1985, Iquitos: Instituto de Investigaciones en la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP)

Silva CG, Herdeiro RS, Mathias CJ, Panek AD, Silveira CS, Rodrigues VP, Rennó N, Falcão DQ, Cerqueira DM, Minto ABM, Nogueira FLP, Quaresma CH, Silva JFM, Menezes FS, Eleutherio ECA: Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Brazilian plants. Pharmacol Res. 2005, 52: 229-233. 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.03.008.

Milliken W: Plants for malaria, plants for fever: medicinal species in Latin America - a bibliographic survey. 1997, Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens

Hoehne FC: Plantas e substancias vegetais toxicas e medicinais. 1939, São Paulo: Graphicars

Barfod A: Usos pasados, presentes y futuros de las palmas Phytelephantoidées (Arecaceae). Las Plantas y El Hombre. Memorias del Primer Simposio Ecuatoriano de Etnobotánica y Botánica Ecónomica. Edited by: Ríos M, Pedersen HB. 1991, Quito: Abya-Yala, 23-46.

Habib FK, Wyllie MG: Not all brands are created equal: a comparison of selected components of different brands of Serenoa repens extract. Prost Can Prostatic Dis. 2004, 7: 195-200. 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500746.

Duke JA: Darien ethnobotanical dictionary. 1968, Columbus: Batelle Memorial Institute

Amorim E, Matias JE, Coelho JC, Campos AC, Stahlke HJ, Timi JR, Rocha LC, Moreira AT, Rispoli DZ, Ferreira LM: Topic use of aqueous extract of Orbignya phalerata (babassu) in rats: analysis of its healing effect. Acta Cir Bras. 2006, 21: 67-76. 10.1590/S0102-86502006000800011.

Baldez RN, Malafaia O, Czeczko NG, Martins NL, Ferreira LM, Ribas CA, Salles JG, Del Claro RP, Santos LO, Garça NL, Araújo LR: Healing of colonic anastomosis with the use of extract aqueous of Orbignya phalerata (babassu) in rats. 2006, 21: 31-38.

Martins NLP, Malafaia O, Ribas-Filho JM, Heibel M, Baldez RN, Vasconncelos PRL, Moreira H, Mazza M, Nassif PAN, Walbach TZ: Healing process in cutaneous surgical wounds in rats under the influence of Orbignya phalerata aqueous extract. Acta Cir Bras. 2006, 21: 66-74.

Batista CP, Torres OJM, Matias JEF, Moreira ATR, Colman D, Lima JHF, Maracri MM, Rauen RJ, Ferreira LM, Freitas ACT: Effect of aqueous extract of Orbignya phalerata (babassu) in the gastric healing in rats: morphologic and tensiometric study. Acta Cir Bras. 2006, 21: 26-31. 10.1590/S0102-86502006000900005.

Matheus ME, Mantovani ISB, Santos GB, Fernandes SBO, Menezes FS, Fernandes PD: Ação de extratos de açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) sobre a produção de óxido nítrico em células RAW 264.7. Rev Bras Farmacog. 2003, 13: 3-5.

Kahn F, Millán B: Astrocaryum (Palmae) in Amazonia a preliminary treatment. Bull IFEA. 1992, 21: 459-531.

Galeano G: Las palmas de la region de Araracuara. Estudios en la Amazonia Colombiana. Edited by: Saldarriaga JG, Van der Hammen T. 1992, Colombia: TROPENBOS, 1: 53-163.

La Rotta C, Miraña P, Miraña M, Miraña B, Miraña M, Yucuna N: Estudio botánico sobre las species utilizadas por la comunidad indígena Miraña, Amazonas, Colombia. WWF-FEN. 1989, 7-23.

Byg A: Las palmas utiles de Nangaritza. Botanica Austroecuatorianas. Edited by: Aguirre Z, Madsen JE, Cotton E, Balslev H. 2002, Quito: Abya-Yala, 375-384.

May AF: Surinaams kruidenboek - sranan hoso dresi. Edited by: Ina Vanderbroek. 1965, Paramaribo: Berghahn Books

Lans C, Harper T, Georges K, Bridgewater E: Medicinal and ethnoveterinary remedies of hunters in Trinidad. BMC Complem Alternat Med. 2001, 1: 10-10.1186/1472-6882-1-10.

Habib FK, Ross M, Ho CKH, Lyons V, Chapman K: Serona repens (Permixon) inhibits the 5L-reductase activity of human prostate cancer cell lines without interfering with PSA expression. Int J Cancer. 2005, 114: 190-194. 10.1002/ijc.20701.

Broseghini S, Frucci S: El cuerpo humano, enfermedades, y plantas medicinales. 1986, Quito: Abya-Yala, 83-85.

Russo EB: Headache treatments by native peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon: a preliminary cross-disciplinary assessment. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992, 36: 193-206. 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90044-R.

Marinho BG, Herdy SA, Sá AC, Santos GB, Matheus ME, Menezes FS, Fernandes PD: Atividade antinociceptiva de extractos de açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Rev Bras Farmacog. 2003, 12: 52-53.

Acosta-Solis M: Vademecum de lantas Medicinales del Ecuador. 1992, Quito: Abya-Yala

Mora-Uprí J, Weber J, Clement C: Peach palm. Bactris gasipaes Kunth. 1997, Rome: IPGRI

Hirose Y, Lipayon IL, Kirinoki M, Chigusa Y, Matsuda H: Development of the rapid and simple ELISA (whole blood-ELISA) using coconut water-tween as a wash solution for whole blood sample from Schistosoma japonicum - infected rabbit and human. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Pub Health. 2005, 36: 1383-1387.

Gertsch J, Stauffer W, Narváez A, Sticher O: Use and significance of palms (Arecaceae) among the Yanomamï in southern Venezuela. J Ethnobiol. 2002, 22: 219-246.

Moore SJ, Hill N, Ruiz C, Cameron MM: Field evaluation of traditionally used plant-based insect repellents and fumigants against the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi in Riberalta, Bolivian Amazon. J Med Entomol. 2007, 44: 624-630. 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[624:FEOTUP]2.0.CO;2.

Lorenzi H: Palmieiras no Brasil nativas e exóticas. 1996, Brazil: Editora Plantarum

Wilbert J: Geography and telluric lore of the Orinoco Delta. J Lat Am Lore. 1975, 5: 129-150.

Toursarkissián M: Plantas medicinales de la Argentina. 1980, Buenos Aires: Ed. Hemisferio Sur

Colares MN, Delucchi G, Nova MC, Vizcaino CE: Anatomia y etnobotanica de las especies medicinales de monocotiledoneas de la estepa pampeana: Alismataceae, Araceae y Arecaceae. Acta Farm Bonaer. 1997, 16: 137-143.

Ticktin T, Dalle SP: Medicinal plant use in the practice of midwifery in rural Honduras. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96: 233-248. 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.015.

Balick MJ: Amazonian oil palms of promise: a survey. Econ Bot. 1979, 33: 11-28. 10.1007/BF02858207.

Cardenas M: Manual de plantas economicas de Bolivia. 1969, Cochabamba: Imprenta Ichthus

Gallegos RA: Etnobotanica de los Quichuas de la Amazonia Ecuatoriana. Miscel antropol Ecu Ser monográfica. 1988, 7: 108-109.

Cerón CE: Etnobiologia de los Cofanes de Dureno Provincia de Sucumbíos, Ecuador. 1995, Quito: Abya-Yala, 47-49.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Krzysztof Kmieć from the Pharmacology Department of Jagiellonian University and Monika Kujawska from the Faculty of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology of the University of Wroclaw and three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions to the manuscript. We thank Elsa Rengifo from the Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonia Peruana and the members of Proyecto Araucaria XXI Nauta from the Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo for sharing their knowledge during field work in the Peruvian Amazon. JS is grateful for an ERASMUS grant that permitted her to study at the University of Aarhus for a year, during which this paper was drafted, and to the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant no. N 305 022036) for supporting her ethnobotanical research. HB is grateful to the Danish Natural Science Research Council (#272-06-0476) for supporting his palm research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The article was initiated by JS, who searched the literature and made the preliminary report on medicinal palms. The manuscript was prepared by JS and HB. Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Joanna Sosnowska and Henrik Balslev contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

13002_2009_173_MOESM1_ESM.PDF

Additional file 1: Clinical categories for disorders that are treated with use of American palms. This table provides a comprehensive list of the data collected on ethnomedicines derived from American palms. The data are organized by ailment, and includes: the associated disease, the palm species, the way the medicine is prepared, the part of the palm that is used, the country that uses the ethnomedicine, the region of that country, the indigenous group of people that use the medicine, and the reference for the finding [83–151]. (PDF 335 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sosnowska, J., Balslev, H. American palm ethnomedicine: A meta-analysis. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 5, 43 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-5-43

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-5-43