Abstract

Background

The Quilombola communities of Ipiranga and Gurugi, located in Atlantic Rainforest in Southern of Paraíba state, have stories that are interwoven throughout time. The practice of meliponicultura has been carried out for generations in these social groups and provides an elaborate ecological knowledge based on native stingless bees, the melliferous flora and the management techniques used. The traditional knowledge that Quilombola have of stingless bees is of utmost importance for the establishment of conservation strategies for many species.

Methods

To deepen study concerning the ecological knowledge of the beekeepers, the method of participant observation together with structured and semi-structured interviews was used, as well as the collection of entomological and botanical categories of bees and plants mentioned. With the aim of recording the knowledge related to meliponiculture previously exercised by the residents, the method of the oral story was employed.

Results and discussion

Results show that the informants sampled possess knowledge of twelve categories of stingless bees (Apidae: Meliponini), classified according to morphological, behavioral and ecological characteristics. Their management techniques are represented by the making of traditional cortiço and the melliferous flora is composed of many species predominant in the Atlantic Rainforest. From recording the memories and recollections of the individuals, it was observed that an intricate system of beliefs has permeated the keeping of uruçu bees (Melipona scutellaris) for generations.

Conclusion

According to management techniques used by beekeepers, the keeping of stingless bees in the communities is considered a traditional activity that is embedded within a network of ecological knowledge and beliefs accumulated by generations over time, and is undergoing a process of transformation that provides new meanings to such knowledge, as can be observed in the practices of young people.

Resumo

Introdução

As comunidades quilombolas de Ipiranga e Gurugi, localizadas na Zona da Mata Sul Paraibana, possuem histórias que se entrecruzam ao longo dos tempos. Encontra-se nesses grupos sociais a prática da meliponicultura realizada desde as antigas gerações, fornecendo assim um elaborado conhecimento ecológico, baseado nas abelhas nativas sem ferrão, na flora melífera e nas técnicas de manejo utilizadas. O conhecimento tradicional que os Quilombola possuem sobre as abelhas indígenas sem ferrão é de extrema importância para o estabelecimento de estratégias conservacionistas de diversas espécies.

Métodos

Para conhecer e aprofundar o estudo sobre o conhecimento ecológico dos meliponicultores foi utilizado o método da observação participante juntamente à realização de entrevistas não estruturadas e semi-estruturadas, além da coleta entomológica e botânica das categorias de abelhas e plantas citadas. Com a intenção de registrar os saberes relacionados à meliponicultura exercida antigamente pelos moradores foi empregado o método da história oral.

Resultados e discussão

Os resultados demonstram que no total os entrevistados conhecem uma riqueza de doze categorias de abelhas sem ferrão (Apidae: Meliponini) e classificam-nas de acordo com características morfológicas, comportamentais e ecológicas. Suas técnicas de manejo são representadas pela feitura tradicional do cortiço e a flora melífera é composta de variadas espécies predominantes na Mata Atlântica. A partir do registro das memórias e recordações dos indivíduos foi percebido que um intricado sistema de crenças permeia a criação de abelha uruçu (Melipona scutellaris) desde gerações passadas.

Conclusão

De acordo com as técnicas de manejo utilizadas pelos meliponicultores, a criação de meliponíneos nas comunidades é compreendida como uma atividade de caráter tradicional, que se encontra envolvida numa rede complexa de conhecimentos ecológicos e crenças construídos pelas diferentes gerações ao longo do tempo, e que vêm passando por um processo de transformações e ressignificações dos saberes como pode ser visto, principalmente, nas práticas dos mais jovens.

Palavras-chave

Comunidades Remanescentes de Quilombos, Abelhas sem ferrão, Uruçu boca-de-renda e Etnoecologia

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

For a long time, human societies have maintained a close relationship with stingless bees, mainly because of their interest in honey, the best-known bee product [1]. Besides their honey and pollen production, nowadays stingless bees have been recognised for their role as the providers of ecosystem services such as pollination of crops and native flora. These social insects occur mainly in Latin America and Africa, particularly in tropical America, and show an expressive diversity and richness of species [2]. In Brazil, Hans Staden was the first to record stingless bees in his book, Warhaftig Historia, (1557). Chapter 35 of the book outlines the characteristics of these bees in Brazil, mentioning their typical behaviour, their nesting in hollow trees and the different qualities of honey, as well as describing how the Indians collected honey [3].

With around 600 species stingless bees are representatives of the order Hymenoptera, family Apidae, sub-family Apinae, belonging to the tribe Meliponini [4]. They are also called meliponines (or even native bees and indigenous bees) and belong to a group of bees characterised by the atrophied or absent sting and which, according to a recent list of Camargo and Pedro [5], include 33 genera.

Among the economic, social and cultural relationships between the stingless bees and human societies throughout time, the medicinal use of the resources obtained or derived from them to treat human diseases is notable [6]. The literature contains records concerning the use of honey, pollen, cerumen (wax mixed with plant resins by the bees), larvae, combs, propolis and even batumen to cure several diseases [6–11].

The activity of keeping meliponines, meliponiculture [12], is very common among Brazilian populations and has been performed for centuries by rural populations (mainly from the north and northeast) and traditional communities (such as indigenous people and Quilombolas). Some studies have already been carried out in Brazil, dealing with the relationships among traditional populations and stingless bees [e.g.[13–25]. Internationally, some studies in this field can also be cited [e.g.[26–31].

The observations and daily practices involved in keeping meliponines for generations, provide such groups with a complex framework for bees, melliferous flora and the ecological relationships between them. Such knowledge is involved in a complex and is integrated by a group of perceptions (corpus), productive practices (praxis) and system of beliefs (kosmos), called a kosmos-corpus-praxis complex by Toledo and Barrera-Bassols [32]. The inter-relationship of these aspects rests on knowledge (corpus) of human populations and is implemented in the daily practices (praxis) and represented in their cultural and symbolic plurality (kosmos).

The integration of this complex represents an ethnoecological focus of study, defined as “the field of trans-disciplinary research which studies thoughts, feelings and behaviours which intermediate the interactions among the human populations that have them and the other elements of the ecosystems which include them [33]. The importance of ethnoecological studies, as well as related areas of knowledge such as ethnobiology, ethnozoology and ethnobotany, have been emphasized especially among conservation biologists [34, 35].

In the context of ethnoecological research in Brazilian Quilombola communities is necessary to highlight the large representation of these groups in the population, since about over 2,272 Quilombola communities have been certified by the Brazilian government since 1988 [36]. Thus, these groups are characterized and selfrecognize themselves by presenting their own ethnic identity, marked by common ancestry and distinct forms of social and political organization.

The Quilombola communities are also characterised by the existence of a specific territory [37], which is translated as the lands of common use and is marked by a diversity of situations where natural resources are appropriated, including usage and property of a private and common character, coupled with ethnic factors, family relationships with cooperation and co-participation [38]. Thus, the lands of common use demonstrate that family unity is an essential element, which supports an autonomous production system based on forms of cooperation among different families.

The practice of meliponiculture is associated with the appropriation of natural resources in Quilombola communities and can contribute towards the construction of local sustainability, in view of environmental sustainability. Meliponiculture is an activity that encourages the conservation of stingless bees, ensuring the pollination of native species and plantations, as well as helping to reduce deforestation and damage to the environment.

To investigate the existence of traditional knowledge and pratices of meliponiculture in Quilombola communities, the present study aims to address the following issues: i) identify native bees known to local beekeepers, as well as the characteristics used in bee categories classification, ii) describe the management techniques used by local beekeepers, iii) conduct a survey of melliferous flora, according to the knowledge of local beekeepers, iv) record the traditional beekeeping practices exercised by residents of the communities since ancient times, as well as the symbolic constructions associated with such practices. We hypothesize that: i) the Quilombola communities maintain traditional practices of meliponiculture verbally transmitted through generations. ii) both Quilombola communities share similar practices and traditional knowledge of meliponiculture.

Methods

Study area

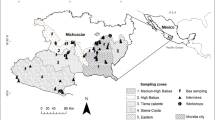

The Quilombola communities of Ipiranga and Gurugi are located in the municipality of Conde in the state of Paraíba (Figure 1). The municipality of Conde is located to the south of the state capital, João Pessoa (07°15′36″S, 34°54′28″W), in the meso-region of Atlantic Rainforest in Paraíba state. The climate is rainy tropical with a dry summer and the vegetation is predominantly composed by sub-deciduous forest and savannah [39].

The communities are approximately 6 km from the centre of Conde and are located on the state highway PB-018 and are adjacent to each other (Figure 2). According to Silva and Dowling [40], a total of 250 families inhabit these two communities and focus their source of income primarily on family farming and fishing, and other extractive activities. Moreover, preserve cultural expressions that are well represented by the dance coco de roda.

Procedures

The research was carried out between May 2011 and November 2012. Initially, the participant observation method was used [41] from visits, participation in meetings and celebrations. This phase was accompanied by informal interviews and a field journal [42]. The choice of informants was performed via the technique of “snow ball” intentional sampling [43], which consisted of an initial meeting with a beekeeper of the region, which led to meetings with others. Following this selection technique, an investigation was undertaken of all families in the communities, which resulted in the recognition of a total of 10 beekeepers (seven in the community of Ipiranga and three in the community of Gurugi), aged between 27 and 87, eight men and two women. Thus, all informants represent the total number of practitioners of this activity among the 250 families.

Non-structured and semi-structured interviews were carried out with the 10 informants [44], and non-structured interviews were performed according to the methodology of data collection [45]. The bee colonies of the informants were then visited and the honey-collecting process was observed, amongst other activities. Among the informants, “native specialists” were chosen according to the criteria of self-recognition and recognition by their own community as being culturally competent [46].

The bee species collected were stored in the Entomology Laboratory of the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB). The identification of the categories that contained the bees already mentioned but that were not found in the region, was carried out using samples belonging to the collection of the laboratory, which were taken from the field, together with pictures of nests of these species. During the collection of the species from the melliferous flora, a guided tour was performed [47] with one of the research informants and the species collected were identified and deposited in the Herbarium Lauro Pires Xavier of the UFPB.

During the recording of the traditional practices of meliponiculture exercised by the residents of these communities since ancient times, the oral story method was used [48]. Seven informers were chosen for the interviews of oral stories, based on the criterion of a family relationship with old stingless bee keepers in the two communities. Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics committee of Universidade Estadual da Paraíba and consent was obtained from the informers for the publication of this report and any accompanying images. The permission of the syndicate of Quilombola communities (Associação da Comunidade Negra do Ipiranga, and Associação da Comunidade Negra do Gurugi) was also required to interview the beekepers.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using an essentially qualitative approach [49]. The field notes were organised as reminders, extensive field notes, and a field journal [44]. The interviews were faithfully transcribed and, where necessary, the consistency and validity of the information collected were checked by the creation of synchronic and diachronic situations [50].

All the data were organised and subsequently selected and condensed as tables and diagrams. Finally, the analysis followed the emic and etic approach, in which the etic mode was considered the way in which the culture members under study perceive, structure, classify and articulate their universe, integrated into the etic mode defined as how the researcher perceives the studied culture.

Results and discussion

Identification and classification of the bees

All the informants recognised a total of 12 categories of stingless bees (Table 1). The species cited were Melipona scutellaris (10 citations); Melipona subnitida (10 citations); ““uruçu-boi” (2 citations); Partamona littoralis (10 citations); Plebeia flavocincta (10 citations); Frieseomelitta francoi (10 citations); Trigona spinipes (10 citations); Frieseomelitta dispar (3 citations); Scaptotrigona sp. “abelha-canudo do cano grosso” (2 citations); Scaptotrigona sp. “abelha-canudo do cano fino” (2 citations); Scaptotrigona aff. tubiba (2 citations); “mumbuca” (2 citations).

The bees were classified according to their behaviour, i.e., whether aggressive or calm, as mild bee or fierce bee. The category mild bee was used to classify uruçu boca-de-renda and the mosquito bee because they are stingless. Alternatively, fierce bee was used to denote specifically tubiba, characterised by its aggressive behaviour of biting the beekeeper during honey collection.

Other studies have also recorded the categorisation of stingless bees as mild or fierce[19, 20, 24, 25]. However, in Léo Neto [25] and Rodrigues [24] the category fierce bee was used to designate stinging bees (= “italian” bees, africanized Apis mellifera).

Regarding the behaviour of the bees within their nest, the informant recognised the category of queen bee when they referred to the bee which is the only one in the colony and has a larger size than the other bees of the nest. In addition, other two categories were recognised: foragers and guard bees. Foragers bees are those that fly into the fields and search for food resources and guard bees remain at the entrance of the nest (Figure 3).

The bees were classified by the informants according to morphological characteristics (shape, presence or absence of sting, size, and standard color), behaviour (presence or absence of aggressiveness) and ecological characteristics (nesting places, external and internal characteristics of the nest, dietary habits, characteristics and honey production) (Table 2). Zamudio and Hilgert [29] identifying the elements that the local population from northern Argentina uses to classify the stingless bees, also reported morphological (shape, size and color), behavioral (docile, aggressive or shy) and ecological characteristics (external and internal characteristics of the nest).

However, among the Kayapó Indians in the Amazon [18] and the Atikums in Pernambuco [25], other characteristics little known to the ethnoentomologists were used in the classification of stingless bees, such as differences in flight and the smell that each species exudes.

As recorded by Costa-Neto [19] during study of the Pankararés, in the taxonomic system of the communities studied here, the presence of a prototypical taxon, the legitimate uruçu was noted. The informants frequently attribute specific properties to uruçu boca-de-renda, in terms of the characteristics of the production and medicinal quality of their honey. According to them, uruçu collects resources from specific flowers to produce honey and, for this reason, their honey is medicinal. Thus, it is often called legitimate uruçu, compared to uruçu-mirim and uruçu-boi.

Products used by the beekeepers

In the communities, honey, cerumen and saburá (pollen) are used. As mentioned previously, the honey produced by uruçu boca-de-renda is considered the best honey by all informants, because of its medicinal properties. Thus, uruçu boca-de-renda is the bee that permeates all meliponiculture in the communities of Ipiranga and Gurugi for generations, with their honey widely being used in the treatment of several diseases throughout the years (Table 3).

Oliveira et al. [8] describe the use of uruçu honey (Melipona scutellaris) for mouth ulcers in children and flu. Moreover, in a review conducted on the use of animal remedies in traditional medicine in Latin America, Alves and Alves [6] also mention the use of uruçu honey in the treatment of coughs, oral fungal infections, eye problems, cataracts and weakness.

Currently, the honey is mostly exchanged among the families rather than being bought and sold. Thus, the communal use of the melliferous resources was a characteristic noted among the residents, since the honey is always given or exchanged for other resources.

When questioned about the procedure carried out by the bees during honey production, there is a consensus among the informants that the process corresponds to the science of the bees and it is very difficult to be understood by humans. Oliveira [20] reports that the rubber tappers and the Kaxinawá tribe from the upper Juruá River also do not know about the process of honey production and they state that its method of production is a mystery, which is presented as “the great science of the bees”.

The main use of cerumen comes from the virgin cerumen, which is the cerumen removed from the honey pots when it is collected and put to dry in the sun, without being eaten (Figure 4). The virgin cerumen is employed in the smoking of the nests, when the honey is collected, with the aim of calming down the bees and it also has medicinal uses, such as for ear ache, healing wounds and the blockage of airways.

The informants refer to the pollen stored in pots by the bees for their feeding as saburá. As well as among the rubber tappers and the Kaxinawás from the upper Juruá River [20], the beekeepers remove the saburá from the colonies at the moment of honey collection and throw it away (Figure 5), thus it is not used for any purpose. However, Souto et al. [10] describe the use of the saburá from cupira bees (Partamona seridoensis) in ethnoveterinary procedures in northeastern Brazil.

Keeping the stingless bees

The bees managed are uruçu boca-de-renda, moça-branca, mosquito bee and jandaíra.

When moça-branca, mosquito bee and jandaíra are managed, the informants from both communities use rustic boxes, which are bought or made by themselves. However, the bee uruçu is more frequently managed being kept by 90% of informants. This bee is managed by both communities via the traditional technique of cortiço, which consists of removing hollow trunks of trees in which the nests are located, closing the extremities with clay and transporting them to their houses (Figure 6). However, the practice of keeping bees in cortiços is currently being replaced, especially by the younger beekeepers, by rustic boxes. When they were questioned about this change, the younger informants answered that the rustic boxes make bee management easier (Figure 7).

One of the informants, who was characterised for this research as a “native specialist”, was committed to transmitting the cortiço technique, by teaching it to his children and grandchildren and resisting the transfer all of his colonies to rustic boxes. According to Giddens [51], the tradition has “guardians”, who are those who identify the details of the traditions via interaction with others of the same age and teach them to the youth. The “tradition guardians”, for Giddens [51], are those who have a connection with the truths that traditions contain or reveal, and these truths are manifested in the interpretations and practices of the “guardians”.

With regard to the artificial division of the colonies, the informants report that this occurs infrequently, only when there is a need to duplicate the original colony to increase honey production. According to them, it is firstly necessary to find a new cortiço (or box) that will shelter the new colony that will result from the division and then some honeycombs from the original nest are placed in the new one. This should be placed exactly in the same location as the original nest, which is allocated a new site. Following this, the new nest will receive the foragers that return with the food resources collected and, thus, the new colony will be established.

There is no consensus among the informants regarding the frequency of honey collection; some of them collect it every three months, others every six months and others do not have a defined time. However, the general consensus is that the best time to collect honey is during the spring, mainly between September and the middle of January, which is called flower time. When the collection is carried out, the honey pots are pierced with a piece of wood and the cortiço is inclined to the side which has a small orifice where the honey flows. The honey is then strained through a clean cloth and stored in glass bottles.

According to the informants, the productivity of uruçu colonies varies from 4 L to 8 L of honey a year per colony. In contrast, the moça-branca, mosquito and jandaíra colonies produce a lower amount of honey, yielding less than 1 L a year per colony.

The most mentioned predator by the informants was the lizard (Tropidurus hispidus and Hemidactylus mabouia), which remains at the entrance to the cortiço or the boxes. Lizard control is performed by either placing a piece of aluminium, a can or a plastic bottle at the entrance of the nest (Figure 8).

The melliferous flora

The communities are located in Atlantic Rainforest region of Paraíba state, which over time has been replaced by large monocultures of sugar cane, a characteristic of the economic expansion of the region. When asked about the preference of the bees for a particular environment of the region, the informants were unanimous in indicating the paús, which are shady environments with remnants of trees, forming dense vegetation coverage and having an abundance of water (Figure 9).

When questioned about the sites of stingless bees nests, the informants reported that the bees make their nests in large trees, and did not mention any particular plant.

However, concerning the collection of food resources, the relationship between stingless bees and specific flowers, which are sought by the bees for honey production was emphasised. Thus, 17 categories of plants (Table 4) which, according to the informants, are the most visited ones by the stingless bees in the region, were defined. It is noteworthy that the beekeepers plant some of these trees in their crops.

Symbolic constructions involving meliponiculture in the communities

The symbolic representations constructed around meliponiculture in the communities of Ipiranga and Gurugi are numerous. An intimate relationship between meliponiculture activity and such symbolic representations is present, mainly among elderly people, regarding beliefs and rituals. Such symbolic systems are understood here as learning tools, knowledge and communication among the group components, when a social integration and a construction of their cultural meanings are established [52].

The main ritual that is practiced concerns the collection of the honey produced by the uruçu boca-de-renda, when sexual abstinence is always practiced for three days before the day scheduled for collection. Thus, as soon as the collection is scheduled, both the beekeeper and other people involved in the process (men or women) are required to abstain from sex for three days prior to this date. According to the informants, if this requirement is not accomplished, the bees will bite the beekeeper and not allow the honey collection and, shortly after, the entire colony will migrate to another region.

Curiously, the practice of sexual abstinence is also noted among other groups of Afro culture, such as in the maracatu de baque solto or maracatu rural (a cultural manifestation of folk music) from Atlantic Rainforest region of Pernambuco state. The caboclo de lança, who is a character of the maracatu rural, practices sexual abstinence several days before carnival. This ritual involves the preparation of the group for the parade, when they perform in the streets of the cities [53].

There are temporal restrictions for females regarding the honey collection of uruçu bees, since a woman cannot approach the nest if she is in her menstrual or pre-menstrual tension period. Thus, keeping stingless bees is characterised as an almost exclusively male activity in the communities.

In De Sangrias, Tabus e Poderes (Of Bleedings, Taboos and Powers), Sardenberg [54] suggests considering menstruation from a social and anthropological perspective and concludes that in many societies, menstruation is seen as a “polluting agent, gifted with impurities or a possessor of magical powers, generally evil”. Among many examples, the author cites the Ojibwas, who are natives of Canada involved in hunting, who consider the proximity of menstruating women as “dangerous and evil to that important activity for the subsistence of the group”.

The uruçu is considered by the informants as a sacred bee. According to them, uruçu bees “rezam o ofício” (pray) every Saturday and during the whole of May. Thus, during this period, they do not collect the honey from the nests from respect to the praying of the bees.

During study of the daily life of fishermen in the lower São Francisco in the state of Alagoas, Marques [33] observed the behaviour of those who “left the lagoon rest”, raising the question of the intentionality of such behaviour as an efficient conservation mechanism. The scientific field of ethnoconservation can be seen as a “new science of conservation”, which aims to meet both environmental and cultural needs and includes the traditional communities as “inborn allies in this exercise” [55].

The symbolic constructions reported here are embedded within a wider context that also covers the knowledge and the productive practices of the beekeepers. Only through the analysis of this group is it possible to understand the relationships between knowledge, interpretation and the management of natural resources by the communities in the construction of their worldview.

Conclusions

The keeping of stingless bees in the communities is considered a traditional activity, which is involved in an ecological knowledge network constructed by different generations over time. The technique of making the cortiço characterized as the main traditional practice is orally transmitted from the generations over time.

The two communities share knowledge and similar management techniques well represented by the use of cortiços and the beliefs that underlie the creation of the uruçu bee.

The honey collected is a product of major importance in the medicinal tradition of the communities. It is largely used as a medicine to combat several diseases and is characterised as a product of “common use” amongst the residents of the communities, since it is always donated or exchanged, thus establishing a commercial relationship based on family unity and personal relationships.

A process of transformation has occurred in the meliponiculture activity of the communities, which is clear from the practices of the youth regarding elderly people. The use of rustic boxes to replace the cortiços, as well as the questioning of beliefs and rituals are characteristics performed by young people. These are seen, in most cases, as practices that unite (but not without conflict), the knowledge of the elderly and the new attitudes of the young people. Thus, a process of transformation and redefinition of meliponiculture practice has occurred, giving a cultural dynamic to the activity, as a demonstration that tradition is not static and is redefined in each generation.

Finally, the importance of biological and cultural diversity is emphasised here, in the study of the relationships between Brazilian Quilombola communities and beekeeping. These studies highlight the relationship between Quilombola communities residents and their beekeeping practices associated to the conservation of natural areas since these communities possess such knowledge.

References

Bradbear N: Beekeeping and Sustainable Livelihoods. 2003, Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome

Nogueira-Neto P: Vida e criação de abelhas indígenas sem ferrão. 1997, Editora Nogueirapis: São Paulo

Engels W: Staden’s first report in 1557 on the collection of stingless bee honey by Indians in Brazil. Pot-honey: a legacy of stingless bees. Edited by: Vit P, Pedro SRM, Roubik DW. 2013, New York: Springer, 241-246.

Michener CD: The Bees of the World. 2007, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2ª

Camargo JMF, Pedro SEM: Meliponini Lepeletier. Catalogue of Bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) in the Neotropical Region - online version. Edited by: Moure JS, Urban D, Melo GAR. 1836, http://www.moure.cria.org.br/catalogue. Accessed Sep/26/2012

Alves RRN, Alves HN: The faunal drugstore: Animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011, 7: 9-10.1186/1746-4269-7-9.

Posey DA: Folk apiculture of the Kayapó Indians of Brazil. Biotropica. 1983, 15 (2): 154-158. 10.2307/2387963.

Oliveira ES, Torres DF, Brooks SE, Alves RRN: The medicinal animal markets in the metropolitan region of Natal City, Northeastern Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130 (1): 54-60. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.010.

Souto WMS, Mourão JS, Barboza RRD, Mendonca LET, Lucena RFP, Confessor MVA, Vieira WLS, Montenegro PFGP, Lopez LCS, Alves RRN: Medicinal animals used in ethnoveterinary practices of the‘Cariri Paraibano’, NE Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011, 7: 30-10.1186/1746-4269-7-30.

Souto W, Mourao JS, Barboza RRD, Alves RRN: Parallels between zootherapeutic practices in Ethnoveterinary and Human Complementary Medicine in NE Brazil. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 134: 753-767. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.041.

Alves RRN, Neta ROS, Trovão DMBM, Barbosa JEL, Barros AT, Dias TLP: Traditional uses of medicinal animals in the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012, 8: 41-10.1186/1746-4269-8-41.

Nogueira-Neto P: A criação de Abelhas Indígenas sem Ferrão. 1953, Chácaras e Quintais: São Paulo

Posey DA: Ethnoentomological survey of amerind groups in lowland Latin America. The Florida Entomologist. 1978, 61 (4): 452-458.

Posey DA: Wasps, warriors and fearless men: ethnoentomology of the Kayapo Indians of Central Brazil. J Ethnobiol. 1981, I (I): 165-174.

Posey DA: The importance of bees to Kayapó Indians of the Brazilian Amazon. The Florida Entomologist. 1982, 65 (4):

Posey DA: Keeping of stingless bees by the kayapo’ indians of brazil. J Ethnobiol. 1983, 3 (1): 63-73.

Posey DA: Suma Etnológica Brasileira. Edited by: Berta G. 1987a, Ribeiro. Petrópolis: Vozes, Etnoentomologia de tribos indígenas da Amazônia, Volume 1, Etnobiologia.

Posey DA, Camargo JMF: Additional notes on the classification and knowledge of stingless bees (Meliponinae, Apidae, Hymenoptera) by the Kayapó Indians of Gorotire, Pará, Brazil. Ann Carnegie Mus. 1985, 54: 247-253.

Costa-Neto EM: Folk taxonomy and cultural significance of “abeia” (Insecta, Hymenoptera) to the Pankararé, Northeastern Bahia State, Brazil. J Ethnobiol. 1998, 18 (1): 1-13.

Oliveira ML: As abelhas sem ferrão na vida dos seringueiros e dos Kaxinawá do Alto rio Juruá, Acre, Brasil. Enciclopédia da Floresta – O Alto Juruá: práticas e conhecimentos das populações. Edited by: da Cunha MC, de Almeida MB. 2002, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 615-630.

Modercin IF: Etnoecologia Pankararé das abelhas sem ferrão, Raso da Catarina. 2005, Ciências Biológicas, Ecologia, Recursos Ambientais: Bahia. Monografia. Universidade Federal da Bahia

Rodrigues AS: Etnoconhecimento sobre abelhas sem ferrão: saberes e práticas dos índios Guarani M’byá na Mata Atlântica. 2005, Dissertação: Universidade de São Paulo, Ecologia de Agroecossistemas

Santos GM, Antonini Y: The traditional knowledge on stingless bees (Apidae: Meliponina) used by the Enawene-Nawe tribe in western Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2008, 4: 19-10.1186/1746-4269-4-19.

Rodrigues ER: Conhecimento etnoentomológico sobre abelha indígena sem ferrão (Meliponina) e meliponicultura na comunidade de São Pedro dos Bois do estado do Amapá. 2009, Desenvolvimento Regional: Dissertação. Universidade Federal do Amapá

Léo Neto NA: “Na lição da abeia-mestra”: Análise do complexo simbólico e ritualístico do mel e das abelhas sem-ferrão entre os índios Atikum. 2011, Dissertação: Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Ciências Sociais

Vasquez-Davila MA, Solís-Trejo MB: Conocimento uso y manejo de la abeja nativa por los Chontales de Tabasco. Terra e Água. 1991, 2: 29-38.

Vit P, Medina M, Enríquez ME: Quality standards for medicinal uses of meliponinae honey in Guatemala, México and Venezuela. Bee World. 2004, 85 (1): 2-5.

Contreras-Escareño FJ, Becerra-Guzmán F, Universid Nacional Autônoma de México: Abejas nativas en México. Imagen Veterinária. 2004, 4 (1): 16-21.

Zamudio F, Hilgert NI: Descriptive attributes used in the characterization of stingless bees (Apidae: Meliponini) in rural populations of the Atlantic forest (Misiones-Argentina). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2012, 8: 9-10.1186/1746-4269-8-9.

Ayala R, Gonzalez VH, Engel MS: Mexican stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae): diversity, distribution and indigenous knowledge. Pot-honey: a legacy of stingless bees. Edited by: Vit P, Pedro SRM, Roubik DW. 2013, New York: Springer, 135-152.

Rosales GRO: Medicinal Uses of Melipona beecheii Honey, by the Ancient Maya. Pot-honey: a legacy of stingless bees. Edited by: Vit P, Pedro SRM, Roubik DW. 2013, New York: Springer, 229-240.

Toledo V, Barrera-Bassols N: A etnoecologia: uma ciência pós-normal que estuda as sabedorias tradicionais. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente. 2009, 20: 31-45.

Marques JGW: Pescando pescadores: uma etnoecologia abrangente no baixo São Francisco. 2001, NUPAUB-USP: São Paulo

Albuquerque UP, Silva JS, Campos JLA, Sousa RS, Silva TC, Alves RRN: The current status of ethnobiological research in Latin America: gaps and perspectives. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013, 9: 72-10.1186/1746-4269-9-72.

Alves RRN, Souto WMS: Ethnozoology in Brazil: current status and perspectives. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011, 7: 22-10.1186/1746-4269-7-22.

Brasil: Palmares Fundação Cultural, http://www.palmares.gov.br/quem-e-quem/Accessed Dec/3/2013

Arruti JM: Quilombos. Raça: novas perspectivas antropológicas. Edited by: Pinho O. 2008, Salvador: ABA/Ed. Unicamp/EDUFBA, 315-350.

Almeida AWB: Os Quilombos e as Novas Etnias. Quilombos: identidade étnica e territorialidade. Edited by: O’dwyer EC. 2002, Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 43-82.

Brasil, Ministério de Minas e Energia: Secretaria de Geologia, mineração e transformação mineral. 2005, Recife: Diagnóstico do município de Conde, 4p-

Silva SDM, Dowling GB: O universo feminino retratado nos cocos de roda, em três Comunidades Quilombolas no estado da Paraíba. Fazendo Gênero. 2010, 9: 1-11.

Gil AC: Métodos e técnicas de pesquisa social. 1999, Editora Atlas S.A.: São Paulo, 5ª

Haverroth M: Experiências de pesquisa de campo em etnobiologia: relatos e reflexões. Encontros e desencontros da pesquisa etnobiológica e etnoecológica: os desafios do trabalho em campo. Edited by: Araújo TAS, Albuquerque UP. 2009, Recife: NUPEEA, 181-203.

Bailey K: Methods of social research. 1994, Nova Iorque: The Free Press, 4

Bernard R: Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 1994, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications

Posey DA: Introdução - Etnobiologia: teoria e prática. Suma etnológica brasileira. Edited by: Ribeiro B. 1987b, Petrópolis: Vozes, Volume 1: 15-25. 2

Hays TE: An empirical method for the identification of covert categories in ethnobiology. American Ethnologist. 1976, 3 (3): 489-507. 10.1525/ae.1976.3.3.02a00070.

Spradley JP, Mccurdy DW: The cultural experience: ethnography in complex society. 1972, Tennessee: Kingsport Press of Kingsport

Thompson P: A voz do Passado: história oral. 1998, Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra

Amorozo MCM, Viertler RB: A abordagem qualitativa na coleta e análise de dados em etnobiologia e etnoecologia. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobiológica e etnoecológica. Edited by: Albuquerque UP, Lucena RFP, Cunha LVFC. 2010, Recife: NUPEEA, 65-83.

Maranhão T: Naútica e classificação ictiológica em Icaraí, Ceará: um estudo em antropologia cognitva. 1975, Dissertação de mestrado: Universidade Federal de Brasília

Giddens A: Em defesa da sociologia: ensaios, interpretações e tréplicas. 2001, Ed. UNESP: São Paulo

Bourdieu P: O poder simbólico. 1989, Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil

Bonald Neto O: Os caboclos de lança – azougados guerreiros de Ogum. Antologia do Carnaval do Recife. Edited by: Souto Maior M, Silva LD. 1991, Recife: Fundaj, Ed. Massangana, 279-

Sardenberg CMB: De sangrías, tabus e poderes: a menstruação numa perspectiva sócio-antropológica. Estudos Feministas. 1994, 2 (2): 314-344.

Diegues AC: Etnoconservação: novos rumos para a conservação da natureza. 2000, Hucitec: São Paulo

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the informants and residents of the Quilombola communities of the Ipiranga and Gurugi who kindly shared their knowledge and time. We also thank Capes and CNPq for financial support for the development of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RMAC carried out the field work, and all authors analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

de Carvalho, R.M.A., Martins, C.F. & Mourão, J.d.S. Meliponiculture in Quilombola communities of Ipiranga and Gurugi, Paraíba state, Brazil: an ethnoecological approach. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 10, 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-3