Abstract

Background

Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3 (AKR1C3) is a key steroidogenic enzyme that is overexpressed in prostate cancer (PCa) and is associated with the development of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). The aim of this study was to investigate the correlation between the expression level of AKR1C3 and the progression of PCa.

Methods

Sixty human prostate needle biopsy tissue specimens and ten LNCaP xenografts from intact or castrated male mice were included in the study. The relationship between the level of AKR1C3 expression by immunohistochemistry and evaluation factors for PCa progression, including prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Gleason score (GS) and age, were analyzed.

Results

Low immunoreactivity of AKR1C3 was detected in normal prostate epithelium, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN). Positive staining was gradually increased with an elevated GS in PCa epithelium and LNCaP xenografts in mice after castration. The Spearman’s r values (rs) of AKR1C3 to GS and PSA levels were 0.396 (P = 0.025) and -0.377 (P = 0.036), respectively, in PCa biopsies. The rs of AKR1C3 to age was 0.76 (P = 0.011). No statistically significant difference was found with other variables.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that the level of AKR.

1C3 expression is positively correlated with an elevated GS, indicating that AKR1C3 can serve as a promising biomarker for the progression of PCa.

Virtual slides

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here: http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/7748245591110149.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in men worldwide [1]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a mainstay treatment for metastatic prostate cancer and is initially effective, with an 80-90% remission rate in patients and improved overall survival. However, most of the patients inevitably progress to CRPC [2, 3]. Unfortunately, the median overall survival rate of CRPC is 23 to 37 months from the time of initiation of ADT [4]. Although the definitive mechanism underlying the progression of PCa remains poorly understood, two major mechanisms that result in the reactivation of the androgen axis in CRPC have been extensively studied [5]. One is the activation of the androgen receptor (AR)-mediated signaling pathway either by the amplification, overexpression or mutations of the AR [6, 7]. The other mechanism mediates intratumoral androgen synthesis, involving either the de novo synthesis of AR ligands from cholesterol or the increased conversion of adrenal androgens (e.g., dehydroepiandrosterone or Δ4-Adione) to active androgens [8, 9].

Based on the new theory of intratumoral androgen synthesis in prostate cancer cells, AKR1C3 was found to play a pivotal role in the synthesis of testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which are the most robust stimuli for activation of the growth, proliferation and metastasis of prostate cancer cells. In vitro experiments have shown that AKR1C3 is up-regulated in prostate cancer cells as a survival adaptation in response to T/DHT deprivation [9]. The overexpression of AKR1C3 was found to increase the intracellular synthesis of testosterone from 4-androstene-3,17-dione in LNCaP cells and resulted in resistance to the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride [10]. Dozmorov et al. demonstrated that the overexpression of AKR1C3 promotes angiogenesis and aggressiveness in PC-3 cells [11]. Several studies have reported low or undetectable levels of AKR1C3 in normal prostate epithelia, whereas elevated AKR1C3 levels have been found in localized, advanced or recurrent PCa and CRPC [12, 13]. However, the correlation between the expression levels of AKR1C3 and the progression of PCa is unclear.

Recently, the benefit of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in the diagnosis and treatment of PCa in men was doubted by some researchers because PSA testing is associated with modest reductions in prostate cancer mortality, over diagnosis and over treatment [14]. Therefore, the next generation of PCa biomarkers that are superior to PSA or complement PSA testing should be explored. In our study, 60 human prostate needle biopsy tissue specimens and 10 murine tumor tissue specimens from intact or castrated male nu/nu mice were selected to detect AKR1C3 expression levels. The relationship between the levels of AKR1C3 expression and factors evaluated for PCa progression, including PSA, Gleason score (GS) and age, were analyzed, aiming to investigate whether AKR1C3 may serve as a potential biomarker for the progression of PCa.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

The PCa screening samples were obtained from 2001–2009 in the Prostate Diseases Prevention and Treatment Research Center of Jilin University in Changchun, Jilin province, China. None of the patients had previously undergone radical prostatectomy or other treatments, such as hormone or radiotherapy. In this study, 60 biopsies were selected for the assessment of AKR1C3 expression by immunohistochemistry staining. PCa case inclusion criteria were designated as follows: (1) detection of cancer within each prostate biopsy specimen, (2) GS of the biopsies equal to or greater than 6, and (3) adenocarcinoma specimens only. The clinicopathological features of PCa samples are summarized in Table 1. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin University. The pathological diagnoses were determined by an experienced urological pathologist.

Cell culture and replication of LNCaP xenografts in mice

Human prostate LNCaP cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection at Passage 4. LNCaP cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 Units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. LNCaP cells (4 × 106) were collected in 70 μL PBS and mixed with 70 μL Matrigel Matrix (Becton Dickinson Biosciences). The mixture was injected subcutaneously on one side of the dorsal flank of 6- to 7-week-old male nu/nu mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD). When the tumor volumes reached 100 mm3, the mice were randomized into a sham-operated group (n = 5) and a castrated group (n = 5). Briefly, after the intramuscular injection of general anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine (8.7 mg/100 g and 1.3 mg/100 g body weight, respectively) and the application of 75% alcohol to disinfect the scrotum, a small midline incision was made to expose the testes. The spermatic vessels were tied with 4.0 silk sutures, and the testes were removed. The incision was then closed using 4.0 silk sutures. In sham-operated mice, the skin of the scrotum was incised to expose the testes, followed only by closure of the incision using sutures. The animals were sacrificed at 3 weeks after the initial operation.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies included AKR1C3 (NP6.G6.A6, mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:150, Abcam) and β-actin (mouse polyclonal antibody, 1:1000, Santa Cruz). Secondary antibodies were anti-mouse IgG (1:2000, Proteintech Group).

Immunohistochemistry

Prostate tissue specimens were cut into approximately 4–6-μm-thick sections, mounted and baked at 55°C overnight. The sections were deparaffinized with xylene and re-hydrated in graded ethanol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides with 0.5% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in 10 mM citric acid buffer (pH 6.0) at 121°C for 15 min in an autoclave. The slides were then washed with 0.1 M Tris–HCl at pH 7.6 (Tris) for 5 min and then incubated with Tris containing 10% goat serum to block non-specific binding. Next, the slides were incubated with AKR1C3 mAb (NP6.G6.A6, mouse monoclonal antibody, 1:150, Abcam) at a dilution of 1:200 at 4°C overnight. After washing with Tris, the slides were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000, Proteintech Group) in Tris containing 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h. Following the washes with Tris, HRP-conjugated streptavidin diluted in Tris containing 10% goat serum was added to the slides, which were incubated at room temperature for an additional 40 min. After a 10-min wash in Tris, a DAB-H2O2 substrate was added to the slides and incubated at room temperature for 6 min. The slides were then washed with distilled water and counterstained with hematoxylin. Next, the slides were dehydrated and sealed with Permount Mounting Media for subsequent visualization. The negative controls were handled in the same way except that PBS was applied in place of primary antibody.

AKR1C3 positive-staining exhibits a brown cytoplasmic and/or nuclear stain. Images of AKR1C3-positive cells were acquired from five randomly chosen fields (400×, magnification) per tissue section. The positive cell density was assessed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, United States), and the results are presented as mean optical density (MOD) values. The negative controls were handled in the same way except that PBS was applied in place of a primary antibody.

Statistical analyses

All of the results were analyzed using SPSS software, version 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). One-way ANOVA was used to examine mean differences between groups. The data were recorded as the mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The Spearman’s Rho was applied to test for significant correlations between the variables. P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

The expression of AKR1C3 in human prostate needle biopsy samples

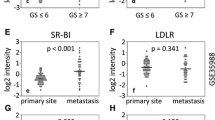

In this study, immunohistochemical staining for AKR1C3 in human prostate needle biopsy tissue specimens, including BPH, PIN and PCa, was carried out. Tissue sections that are representative of the immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal anti-AKR1C3 antibody are shown in Figure 1. In contrast to the negative staining observed in the normal glandular epithelium specimen (characterized by the small nuclei, Figure 1A) and the PBS control (Figure 1D), a few disseminated cells with brown positive immunoreactivity were visualized in the BPH (Figure 1B) as well as in the PIN samples (Figure 1C). Positive cytoplasmic staining was widely observed in the prostate cancer cells (characterized by the larger nuclei) (Figure 1E-H). The distribution of AKR1C3 expression is different between BPH and PCa. For BPH and PIN specimens, positive expression of AKR1C3 was observed in the stromal cells other than the epithelial cells, and for malignant prostate cancer specimens with GS greater than 6, a gradually stronger positive staining of AKR1C3 was detected in prostate cancer epithelial cytoplasm. The data also showed that AKR1C3 expression gradually increased with increasing GS (r s = 0.396, P = 0.025) and slightly increased with age in BPH (r s = 0.76, P = 0.011), but the MOD for positive AKR1C3 expression in prostate tumor tissues was significantly higher than that of the BPH specimens. This result implicated that the levels of AKR1C3 are closely associated with the PCa and GS.

Immunohistochemical staining of AKR1C3 in human prostatic needle biopsies. (A) Normal prostate. (B) BPH. (C) PIN. (D) PBS negative control of prostate cancer tissue. (E)-(H) Different GS prostate cancer tissues. (E) Gleason score = 6. (F) Gleason score = 7. (G) Gleason score = 8. (H) Gleason score = 9. (I) The quantification bar for the MOD of AKR1C3. *P < 0.05, compared with BPH. #P < 0.05, compared with PIN. Scale bar is 50 μm.

The expression of AKR1C3 in castrated mouse prostate cancer models

To further confirm the relationship between the progression of PCa and the expression of AKR1C3, the LNCaP mouse model with or without castration was replicated. The aim of castration was to remove the circulating androgens, and the subcutaneous xenografts recurred at 3 weeks after castration, which reflected the state of prostate cancer progression to CRPC. The LNCaP prostate cancer cell line is androgen-dependent, and the expression levels of AKR1C3 in LNCaP tumors at 3 weeks after castration were significantly increased compared to those of the LNCaP sham tumors with MOD values of 0.081 ± 0.016 to 0.060 ± 0.018 (Figure 2A-C). These results indicate that androgen ablation likely stimulates AKR1C3 gene activation and might be attributed to prostate cancer progression.

The correlation of AKR1C3 expression with clinicopathological features in prostate biopsy samples

In classical Partin tables, GS, PSA and age are key parameters for evaluating the progression of prostate cancer. The correlations of mean AKR1C3 expression with GS, mean PSA and age were analyzed and delineated (Tables 2 and 3). The data showed that AKR1C3 expression gradually increased with increasing GS, as indicated by the MOD, exhibiting a positive correlation (r s = 0.396, P = 0.025). PSA is considered to be a putative maker for PCa progression and recurrence. The Spearman’s r values for PSA with the GS or AKR1C3 were analyzed. Serum PSA levels are not correlated with AKR1C3 (r s = -0.016, P = 0.979) in BPH but are negatively correlated with AKR1C3 expression (r s = -0.377, P = 0.036), which indicates that AKR1C3 is a better marker to reflect the clinicopathological stage and evaluation of PCa progression in those patients with low levels of PSA.

Discussion

Androgens are known to play important roles in the pathogenesis of PCa [15]. Recently, the intratumoral synthesis of androgen from cholesterol or the conversion of adrenal precursor androgens to active androgens represent two important mechanisms underlying the progression of PCa and CRPC [5, 6, 8, 13]. Several studies have indicated that AKR1C3 overexpression increases with PCa progression through the mechanisms underlying the key steroidogenic enzyme AKR1C3, which possesses 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5 (17β-HSD5) activity, and PGF synthesis enzyme [13, 16, 17]. However, the correlation between the quantification of AKR1C3 expression and the progression of PCa is unclear.

In our study, AKR1C3 expression was investigated by immunohistochemical staining of prostate biopsy sections with different GSs. We found that AKR1C3 expression gradually increased with an elevated GS (r s = 0.396, P = 0.025), implicating that AKR1C3 overexpression is closely associated with PCa malignancy. Interestingly, the distribution of AKR1C3 expression is different in PCa and preneoplastic change. For BPH and PIN specimens, most of the positive expression of AKR1C3 was observed in the stromal cells other than the epithelial cells; however, a gradually stronger positive staining of AKR1C3 was detected in the epithelial cells for malignant PCa specimens with GSs greater than 6. It is known that the epithelial cells in normal prostate are dependent on stromal cells secreting EGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), nerve growth factor (NGF) and IGF to support their growth and differentiation [18]. During malignant transformation of prostatic epithelial cells, androgen regulation shifts from paracrine to autocrine and prostatic epithelial cells adaptively acquire the intratumoral androgen synthesis ability to maintain the growth of tumor cells. It is reported that AKR1C3 is a pivotal enzyme in converting Δ4-dione to testosterone [13], 5α-DHT to 3α-diol [7], and androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to intraprostatic testosterone in the progression of PCa and CRPC. Some studies showed that AKR1C3 has a preference in prostate cancer for the androstenedione to DHT by an alternative pathway [19]. Moreover, AKR1C3 possesses 11-ketoprostaglandin reductase activity and is capable of converting PGD2 to 9α, 11β-PGF2α, which promotes prostate cell proliferation through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in androgen receptor-negative PCa [11, 20]. These data indicate that overexpression of AKR1C3 is the adaptive change that maintains tumor cell development and progression, and the consistency of AKR1C3 expression with the GS and higher expression in LNCaP xenografts of castrated mice in our study further strengthen the potential of AKR1C3 as a biomarker of PCa progression.

Recently, the potential prostate cancer biomarkers, such as prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3), TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions and p501s (prostein), were investigated as auxiliary diagnosis candidates for prostate cancer [21–24]. Previous studies showed that poorly differentiated PCa tumors produced relatively little PSA and that PSA levels lost their correlation with PCa aggressiveness [25–28]. Moreover, in CRPC patients, the serum PSA levels are far behind the progression of PCa [26–28]. In our retrospective study of 40 cases of PCa (GS ≥ 6, serum PSA > 4 ng/ml), the AKR1C3 expression level exhibited a positive correlation with the GS (score from 6 to 9) and a negative correlation with PSA levels. Although the correlation index is low in this study, the data still indicate that the expression of AKR1C3 may serve as a promising biomarker for evaluating prostate cancer progression.

Conclusions

Overexpressed AKR1C3, as an adaptive response for the progression of PCa, exhibited a positive correlation with the GS. Our study shed light on the potential of AKR1C3 to serve as a promising biomarker for the progression of PCa.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011, 61 (2): 69-90. 10.3322/caac.20107.

Crawford ED, Eisenberger MA, McLeod DG, Spaulding JT, Benson R, Dorr FA, Blumenstein BA, Davis MA, Goodman PJ: A controlled trial of leuprolide with and without flutamide in prostatic carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1989, 321 (7): 419-424. 10.1056/NEJM198908173210702.

Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, Miller G, McLeod DG, Loehrer PJ, Wilding G, Sears K, Culkin DJ, Thompson IM, Bueschen AJ, Lowe BA: Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339 (15): 1036-1042. 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504.

Hellerstedt BA, Pienta KJ: The current state of hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002, 52 (3): 154-179. 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.154.

Knudsen KE, Penning TM: Partners in crime: deregulation of AR activity and androgen synthesis in prostate cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010, 21 (5): 315-324. 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.002.

Lapouge G, Marcias G, Erdmann E, Kessler P, Cruchant M, Serra S, Bergerat JP, Ceraline J: Specific properties of a C-terminal truncated androgen receptor detected in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008, 617: 529-534. 10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_53.

Reddy GP, Barrack ER, Dou QP, Menon M, Pelley R, Sarkar FH, Sheng S: Regulatory processes affecting androgen receptor expression, stability, and function: potential targets to treat hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2006, 98 (6): 1408-1423. 10.1002/jcb.20927.

Hofland J, van Weerden WM, Dits NF, Steenbergen J, van Leenders GJ, Jenster G, Schroder FH, de Jong FH: Evidence of limited contributions for intratumoral steroidogenesis in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2010, 70 (3): 1256-1264. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2092.

Pfeiffer MJ, Smit FP, Sedelaar JP, Schalken JA: Steroidogenic enzymes and stem cell markers are upregulated during androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. Mol Med. 2011, 17 (7–8): 657-664.

Byrns MC, Mindnich R, Duan L, Penning TM: Overexpression of aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) in LNCaP cells diverts androgen metabolism towards testosterone resulting in resistance to the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012, 130 (1–2): 7-15.

Dozmorov MG, Azzarello JT, Wren JD, Fung KM, Yang Q, Davis JS, Hurst RE, Culkin DJ, Penning TM, Lin HK: Elevated AKR1C3 expression promotes prostate cancer cell survival and prostate cell-mediated endothelial cell tube formation: implications for prostate cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2010, 10: 672-10.1186/1471-2407-10-672.

Fung KM, Samara EN, Wong C, Metwalli A, Krlin R, Bane B, Liu CZ, Yang JT, Pitha JV, Culkin DJ, Kropp BP, Penning TM, Lin HK: Increased expression of type 2 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/type 5 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) and its relationship with androgen receptor in prostate carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006, 13 (1): 169-180. 10.1677/erc.1.01048.

Nakamura Y, Suzuki T, Nakabayashi M, Endoh M, Sakamoto K, Mikami Y, Moriya T, Ito A, Takahashi S, Yamada S, Yamada S, Arai Y, Sasano H: In situ androgen producing enzymes in human prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005, 12 (1): 101-107. 10.1677/erc.1.00914.

Howrey BT, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Goodwin JS: The impact of PSA screening on prostate cancer mortality and overdiagnosis of prostate cancer in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013, 68 (1): 56-61. 10.1093/gerona/gls135.

Lopez-Otin C, Diamandis EP: Breast and prostate cancer: an analysis of common epidemiological, genetic, and biochemical features. Endocr Rev. 1998, 19 (4): 365-396.

Azzarello J, Fung KM, Lin HK: Tissue distribution of human AKR1C3 and rat homolog in the adult genitourinary system. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008, 56 (9): 853-861. 10.1369/jhc.2008.951384.

Wako K, Kawasaki T, Yamana K, Suzuki K, Jiang S, Umezu H, Nishiyama T, Takahashi K, Hamakubo T, Kodama T, Naito M: Expression of androgen receptor through androgen-converting enzymes is associated with biological aggressiveness in prostate cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2008, 61 (4): 448-454. 10.1136/jcp.2007.050906.

Arnold JT, Isaacs JT: Mechanisms involved in the progression of androgen-independent prostate cancers: it is not only the cancer cell’s fault. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2002, 9 (1): 61-73. 10.1677/erc.0.0090061.

Chang KH, Li R, Papari-Zareei M, Watumull L, Zhao YD, Auchus RJ, Sharifi N: Dihydrotestosterone synthesis bypasses testosterone to drive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108 (33): 13728-13733. 10.1073/pnas.1107898108.

Wang S, Yang Q, Fung KM, Lin HK: AKR1C2 and AKR1C3 mediated prostaglandin D2 metabolism augments the PI3K/Akt proliferative signaling pathway in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008, 289 (1–2): 60-66.

Nam RK, Sugar L, Yang W, Srivastava S, Klotz LH, Yang LY, Stanimirovic A, Encioiu E, Neill M, Loblaw DA, Trachtenberg J, Narod SA, Seth A: Expression of the TMPRSS2: ERG fusion gene predicts cancer recurrence after surgery for localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007, 97 (12): 1690-1695. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604054.

Bussemakers MJ, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh GW, Smit FP, Karthaus HF, Schalken JA, Debruyne FM, Ru N, Isaacs WB: DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1999, 59 (23): 5975-5979.

Dabir PD, Ottosen P, Hoyer S, Hamilton-Dutoit S: Comparative analysis of three- and two-antibody cocktails to AMACR and basal cell markers for the immunohistochemical diagnosis of prostate carcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2012, 7: 81-10.1186/1746-1596-7-81.

Yin M, Dhir R, Parwani AV: Diagnostic utility of p501s (prostein) in comparison to prostate specific antigen (PSA) for the detection of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma. Diagn Pathol. 2007, 2: 41-10.1186/1746-1596-2-41.

McGuire BB, Helfand BT, Loeb S, Hu Q, O’Brien D, Cooper P, Yang X, Catalona WJ: Outcomes in patients with Gleason score 8–10 prostate cancer: relation to preoperative PSA level. BJU Int. 2012, 109 (12): 1764-1769. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10628.x.

Ross RW, Xie W, Regan MM, Pomerantz M, Nakabayashi M, Daskivich TJ, Sartor O, Taplin ME, Kantoff PW, Oh WK: Efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with advanced prostate cancer: association between Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and prior ADT exposure with duration of ADT effect. Cancer. 2008, 112 (6): 1247-1253. 10.1002/cncr.23304.

Keto CJ, Aronson WJ, Terris MK, Presti JC, Kane CJ, Amling CL, Freedland SJ: Detectable prostate-specific antigen nadir during androgen-deprivation therapy predicts adverse prostate cancer-specific outcomes: results from the SEARCH database. Eur Urol. 2012, 65 (3): 620-627.

Mulholland DJ: PSA-negative/low prostate cancer cells: the true villains of CRPC?. Asian J Androl. 2012, 14 (5): 663-664. 10.1038/aja.2012.69.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81302206), the Development and Reform Commission of Jilin Province (2013C026-2), the Jilin Provincial Science & Technology Department (20130413022GH), and the Health and Family Planning Commission of Jiangxi Province (20143207).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YT, Ljing Zhao and CX carried out most of experiments, participated in the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. HZ, Ljuan Z, YL and JL helped to edit the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Yuantong Tian, Lijing Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, Y., Zhao, L., Zhang, H. et al. AKR1C3 overexpression may serve as a promising biomarker for prostate cancer progression. Diagn Pathol 9, 42 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-9-42