Abstract

Introduction

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign breast tumors in young women. Infarction is rarely observed in fibroadenomas and when present, it is usually associated with pregnancy or lactation. Infarction can exceptionally occur as a complication of previous fine-needle aspiration biopsy or during lactation and pregnancy.

Materials and methods

Retrospective review of 650 cases of fibroadenomas diagnosed at our institution during the 8-years period identified two cases of fibroadenomas with infarction (rate ~0.3%).

Results

Two partially infarcted fibroadenomas were diagnosed on core biopsy and frozen section in an adolescent girl (13 years old) and in a young woman (25 years old), respectively. No preceding fine-needle aspiration biopsy was performed in these cases, nor were the patients pregnant or lactating at the time of the diagnosis.

Conclusion

Spontaneous infarction within fibroadenoma is a rare phenomenon in younger patients. The presence of necrosis on core biopsy or frozen section should be cautiously interpreted and is not a sign of malignancy.

Virtual Slides

The virtual slide(s) for this article can be found here:http://www.diagnosticpathology.diagnomx.eu/vs/1556060549847356

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign neoplasms of the breast usually affecting adolescents and young women[1, 2]. Infarction in benign breast lesions is rare and may occur in various conditions, including fibroadenomas[1, 3]. Infarction within a fibroadenoma was first described by Delarue and Redon in 1949[4] and usually affects young women during pregnancy or lactation, but may occur at any age following fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA)[1, 5–8].

Clinically, fibroadenoma typically presents as a palpable mass and may occasionally be mistaken for inflammatory lesions due to pain and tenderness or for malignancy due to hardness, fixation to the surrounding tissue or bloody nipple discharge[2, 9, 10].

Spontaneous infarction of fibroadenomas not related to previously mentioned causes occurs exceptionally and only a few cases are described in the available literature[2, 7, 9, 11–14].

Herein, we describe a review of fibroadenomas of the breast with two new cases of spontaneous infarction, unrelated to any known risk factor.

Materials and methods

We did a retrospective search of our database for fibroadenomas of the breast that were diagnosed at our department during the 8 years period (2005–2012). Two cases of fibroadenoma with spontaneous infarction were identified. Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides were retrieved from the pathology archive and retrospectively reviewed (F.S. and S.V.).

In a case #1 immunohistochemical staining against estrogen receptor (ER, clone: 1D5, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and progesterone receptor (PR, clone: PgR636, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) was performed.

Clinical history was available for both cases along with radiologic images (ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]).

Results

Our search revealed 650 fibroadenomas during the period 2005–2012. Infarcted fibroadenomas were diagnosed in two patients (rate 0.3%): an adolescent girl (13 years old, Case #1) and in a young woman (25 years old, Case #2). Both patients had no previous history of pregnancy, lactation or previous FNA. No hormonal disturbances were present in the patients. Postoperative course was uneventful in both patients.

Case 1

A 13-year-old pubertal girl presented with a rapidly growing, mobile and painful mass in the right breast. Radiologic findings (ultrasound and MRI) indicated the presence of a well-circumscribed tumor of the right breast consistent with a juvenile fibroadenoma (BI-RADS Category 2) (Figure1A-B).

Radiologist performed a core needle biopsy that revealed a fibroepithelial lesion exhibiting focal necrosis but without malignant cells (classified as B3 lesion) which led to the immediate excision biopsy, performed a week later (Figure2A).

(A): Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) slide of a core biopsy showing a classical fibroadenoma with an area of necrosis (arrow) (5x); (B): An excision biopsy revealing a fibroadenoma with a focal morphologic features of benign phyllodes tumor (H&E, 10x); (C): A zone of necrosis (H&E, 10x); (D): Squamous metaplasia, observed in close proximity of necrotic foci, reminiscent of the so-called necrotizing syringometaplasia in the skin or necrotizing sialometaplasia in salivary glands (H&E, 10x).

Grossly, the tumor was an encapsulated, soft yellow, measuring 40×35×25 mm with foci of hemorrhage and necrosis. The entire tumor was submitted for microscopic evaluation. Microscopic findings were consistent with partially infarcted benign fibroadenoma with focal increased stromal cellularity resembling that of benign phyllodes tumor (Figure2B-C). Squamous metaplasia, observed in close proximity to the necrotic foci, was present and was reminiscent of the so-called necrotizing syringometaplasia in the skin or necrotizing sialometaplasia in salivary glands (Figure2D).

In Case #1, both epithelial and stromal cells were focally positive for estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) (~20% of the cells with weak to moderate nuclear intensity).

Case 2

A 25-year-old gravida 0, para 0 woman presented to a breast radiologist with a short history of a rapidly growing palpable and painful tumor in the left breast. Clinical and radiologic findings (ultrasound) were suggestive of juvenile fibroadenoma or intraductal papilloma (BI-RADS Category 2) and the patient was referred to the breast surgeon. The excision biopsy was performed and intraoperative frozen section consultation was obtained which read as a benign fibroepithelial tumor with focal intratumoral hemorrhage without signs of malignancy.

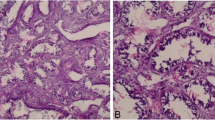

Gross examination revealed a nodular, circumscribed tumor, measuring 25×20×17 mm that was soft, yellow with peripheral areas of hemorrhage. The entire tumor was submitted for histopathologic evaluation which revealed juvenile (cellular) fibroadenoma with foci of hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure3A-B). No evidence of malignancy was found.

Discussion

Fibroadenomas are the most common benign tumors of the breast that usually affect premenopausal women but may occur at any age. Diagnosis of fibroadenoma rarely poses a diagnostic dilemma, even on core biopsy, FNA or frozen section. We presented here two rapidly growing infarcted fibroadenomas that were causing pain. Infarction within fibroadenoma is a very rare event and the frequency of infarction in our study is in line with a study of Haagensen[15] who found only five infarcted cases among 1,000 reviewed breast fibroadenomas (rate: 0.5%). Another two studies based on the series of fibroadenomas in West African women revealed a slightly higher incidence of spontaneous infarction (0.9%)[16, 17]. The highest frequency (3.6%) was reported in a recent study of Al-Atrooshi[18].

The presence of infarction and necrosis are usually worrisome signs in breast pathology although spontaneous infarction can be seen in variety of benign breast lesions including fibroadenoma, phyllodes tumor, lactating adenoma, and intraductal papilloma[3, 19–23]. Spontaneous infraction in fibroadenomas is a rare phenomenon and usually associated with pregnancy, lactation or a recent FNA[5–7]. Exceptionally, spontaneous infarction may affect multiple fibroadenomas in the same patient[24]. Infarction may also be associated with the use of oral contraceptives[25]. Rarely, it can be seen in young patients without any associated risk factors, as illustrated in our two cases. The cause and mechanism of infarction are largely unknown. One of the possible explanations is that infarction represents a spectrum of regressive changes that also may include calcification and hyalinization, both of which are much more commonly seen in fibroadenomas[26]. Newman et al.[27] also found thrombo-oclussive vascular changes as a possible cause of infarction within fibroadenomas.

In our first case, a focus of necrosis was seen on core biopsy which prompted excision biopsy while in the second case clinical suspicion for malignancy prompted an intra-operative frozen section consultation which also revealed the presence of intratumoral hemorrhage and necrosis. A meticulous histopathologic evaluation of the entire tumors, however, revealed no signs of malignancy despite the presence of necrosis. Of note, case #1 also showed areas of squamous metaplasia resembling so-called necrotizing syringometaplasia in the skin or sialometaplasia in salivary glands. This phenomenon has already been described in infarcted breast fibroadenomas[28] and can also be seen in other benign breast lesions in a close proximity to the area of infarction (e.g. intraductal papilloma,[20]).

Fibroadenomas, particularly in older women, may be affected by various proliferative changes including malignant epithelial lesions[29, 30]. The most frequent are in situ carcinomas (both ductal and lobular), and their invasive counterparts[30–32]. Exceptionally, sarcomas may also develop within fibroadenomas (e.g. angiosarcoma, osteosarcoma)[33, 34]. Little is known about the molecular mechanisms that drive the development and prog ression of malignant tumors within fibroadenomas. Comparative studies that analyzed various molecular markers in fibroadenomas and breast carcinomas failed however to identify the potential drivers[35, 36]. However, a clonality study of Kuijper et al.[37] indicated that fibroadenomas possessed a potential to progress in an epithelial direction (carcinoma) or in a stromal direction (phyllodes tumor).

We conclude that partial spontaneous infarction is a rare event in breast fibroadenomas and may not be associated with any known risk factor. The presence of necrosis on core biopsy or intra-operative frozen section should be cautiously interpreted and is not itself a sign of malignancy.

Consent

The case reports were shared with the local ethical committee whose policy is not to review case reports.

References

Rosen PP: Rosen’s breast pathology. 2009, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 3

Liu H, Yeh ML, Lin KJ, Huang CK, Hung CM, Chen YS: Bloody nipple discharge in an adolescent girl: unusual presentation of juvenile fibroadenoma. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010, 51: 190-192. 10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60036-8.

Fratamico FC, Eusebi V: Infarct in benign breast diseases. Description of 4 new cases. Pathologica. 1988, 80: 433-442.

Majmudar B, Rosales-Quintana S: Infarction of breast fibroadenomas during pregnancy. JAMA. 1975, 231: 963-964. 10.1001/jama.1975.03240210043017.

Vargas MP, Merino MJ: Infarcted myxoid fibroadenoma following fine-needle aspiration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996, 120: 1069-1071.

Pinto RG, Couto F, Mandreker S: Infarction after fine needle aspiration. A report of four cases. Acta Cytol. 1996, 40: 739-741. 10.1159/000333949.

Ichihara S, Matsuyama T, Kubo K, Tamura Z, Aoyama H: Infarction of breast fibroadenoma in a postmenopausal woman. Pathol Int. 1994, 44: 398-400.

Lucey JJ: Spontaneous infarction of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 1975, 28: 937-943. 10.1136/jcp.28.12.937.

Oh YJ, Choi SH, Chung SY, Yang I, Woo JY, Lee MJ: Spontaneously infarcted fibroadenoma mimicking breast cancer. J Ultrasound Med. 2009, 28: 1421-1423.

Deshpande KM, Deshpande AH, Raut WK, Lele VR, Bobhate SK: Diagnostic difficulties in spontaneous infarction of a fibroadenoma in an adolescent: case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002, 26: 26-28. 10.1002/dc.10029.

Fowler CL: Spontaneous infarction of fibroadenoma in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Radiol. 2004, 34: 988-990. 10.1007/s00247-004-1250-4.

Toy H, Esen HH, Sonmez FC, Kucukkartallar T: Spontaneous Infarction in a Fibroadenoma of the Breast. Breast Care (Basel). 2011, 6: 54-55. 10.1159/000324047.

Hsu S, Hsieh H, Hsu G, Lee H, Chen K, Yu J: Spontaneous Infarction of a Fibroadenoma of the Breast in a 12-Year-Old Girl. Journal of medical sciences Taipei. 2005, 25: 313-

Meerkotter D, Andronikou S: Unusual presentation and inconclusive biopsy render fibroadenoma in two young females a diagnostic dilemma: case report. SA Journal of Radiology. 2009, 13: 62-65.

Haagensen CD: Diseases of the Breast. 1986, Saunders

Jayasinghe Y, Simmons PS: Fibroadenomas in adolescence. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2009, 21: 402-406. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e32832fa06b.

Onuigbo W: Breast fibroadenoma in teenage females. Turk J Pediatr. 2003, 45: 326-328.

Al-Atrooshi SA: Fibroepithelial tumors of female breast: a review of 250 cases of fibroadenomas and phylloides tumors. The Iraqi Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2012, 11: 140-145.

Verslegers I, Tjalma W, Van Goethem M, Colpaert C, Biltjes I, De Schepper AM, Parizel PM: Massive infarction of a recurrent phyllodes tumor of the breast: MRI-findings. JBR-BTR. 2004, 87: 21-22.

Flint A, Oberman HA: Infarction and squamous metaplasia of intraductal papilloma: a benign breast lesion that may simulate carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1984, 15: 764-767. 10.1016/S0046-8177(84)80168-9.

Behrndt VS, Barbakoff D, Askin FB, Brem RF: Infarcted lactating adenoma presenting as a rapidly enlarging breast mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999, 173: 933-935. 10.2214/ajr.173.4.10511151.

Baker TP, Lenert JT, Parker J, Kemp B, Kushwaha A, Evans G, Hunt KK: Lactating adenoma: a diagnosis of exclusion. Breast J. 2001, 7: 354-357. 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2001.20075.x.

Okada K, Suzuki Y, Saito Y, Umemura S, Tokuda Y: Two cases of ductal adenoma of the breast. Breast Cancer. 2006, 13: 354-359. 10.2325/jbcs.13.354.

Akdur NC, Gozel S, Donmez M, Ustun H: Spontaneous infarction of multiple fibroadenoma in a postlactational woman: case report. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences. 2012, 32: 1429-1432. 10.5336/medsci.2010-22098.

Tavassoli FA: Pathology of The Breast. 1999, McGraw-Hill

Greenberg R, Skornick Y, Kaplan O: Management of breast fibroadenomas. J Gen Intern Med. 1998, 13: 640-645. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.cr188.x.

Newman J, Kahn LB: Infarction of fibro-adenoma of the breast. Br J Surg. 1973, 60: 738-740. 10.1002/bjs.1800600921.

Pandit AA, Deshpande RB: Infarction of fibroadenoma with squamous metaplasia. Indian J Cancer. 1985, 22: 271-273.

Tissier F, De Roquancourt A, Astier B, Espie M, Clot P, Marty M, Janin A: Carcinoma arising within mammary fibroadenomas. A study of six patients. Ann Pathol. 2000, 20: 110-114.

Goldman RL, Friedman NB: Carcioma of the breast arising in fibroadenomas, with emphasis on lobular carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1969, 23: 544-550. 10.1002/1097-0142(196903)23:3<544::AID-CNCR2820230305>3.0.CO;2-F.

Diaz NM, Palmer JO, McDivitt RW: Carcinoma arising within fibroadenomas of the breast. A clinicopathologic study of 105 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991, 95: 614-622.

Cole-Beuglet C, Soriano RZ, Kurtz AB, Goldberg BB: Fibroadenoma of the breast: sonomammography correlated with pathology in 122 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983, 140: 369-375. 10.2214/ajr.140.2.369.

Babarovic E, Zamolo G, Mustac E, Strcic M: High grade angiosarcoma arising in fibroadenoma. Diagn Pathol. 2011, 6: 125-10.1186/1746-1596-6-125.

Killick SB, McCann BG: Osteosarcoma of the breast associated with fibroadenoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1995, 7: 132-133. 10.1016/S0936-6555(05)80817-9.

Bal A, Joshi K, Logasundaram R, Radotra BD, Singh R: Expression of nm23 in the spectrum of pre-invasive, invasive and metastatic breast lesions. Diagn Pathol. 2008, 3: 23-10.1186/1746-1596-3-23.

Xu X, Jin H, Liu Y, Liu L, Wu Q, Guo Y, Yu L, Liu Z, Zhang T, Zhang X, Dong X, Quan C: The expression patterns and correlations of claudin-6, methy-CpG binding protein 2, DNA methyltransferase 1, histone deacetylase 1, acetyl-histone H3 and acetyl-histone H4 and their clinicopathological significance in breast invasive ductal carcinomas. Diagn Pathol. 2012, 7: 33-10.1186/1746-1596-7-33.

Kuijper A, Buerger H, Simon R, Schaefer KL, Croonen A, Boecker W, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ: Analysis of the progression of fibroepithelial tumours of the breast by PCR-based clonality assay. J Pathol. 2002, 197: 575-581. 10.1002/path.1161.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Zoran Gatalica, MD, DSc, Caris Life Sciences, Phoenix, Arizona, United States of America for proof reading the manuscript and critical comments.

The preliminary results of the study were in part presented at the XXIX International Congress of the International Academy of Pathology, Cape Town, South Africa, 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

SV and FK have been directly involved in diagnosis and interpretation of patient’s diagnosis. FS and SV conceived the study design. All authors wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Skenderi, F., Krakonja, F. & Vranic, S. Infarcted fibroadenoma of the breast: report of two new cases with review of the literature. Diagn Pathol 8, 38 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-38

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-8-38