Abstract

Background

Cushing's Syndrome (CS) which is caused by isolated Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) production, rather than adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) production, is extremely rare.

Methods

We describe the clinical presentation, course, laboratory values and pathologic findings of a patient with isolated ectopic CRH causing CS. We review the literature of the types of tumors associated with this unusual syndrome and the behavior of these tumors by endocrine testing.

Results

A 56 year old woman presented with clinical and laboratory features consistent with ACTH-dependent CS. Pituitary imaging was normal and cortisol did not suppress with a high dose dexamethasone test, consistent with a diagnosis of ectopic ACTH. CT imaging did not reveal any discrete lung lesions but there were mediastinal and abdominal lymphadenopathy and multiple liver lesions suspicious for metastatic disease. Laboratory testing was positive for elevated serum carcinoembryonic antigen and the neuroendocrine marker chromogranin A. Serum markers of carcinoid, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and pheochromocytoma were in the normal range. Because the primary tumor could not be identified by imaging, biopsy of the presumed metastatic liver lesions was performed. Immunohistochemistry was consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor, specifically small cell carcinoma. Immunostaining for ACTH was negative but was strongly positive for CRH and laboratory testing revealed a plasma CRH of 10 pg/ml (normal 0 to 10 pg/ml) which should have been suppressed in the presence of high cortisol.

Conclusions

This case illustrates the importance of considering the ectopic production of CRH in the differential diagnosis for presentations of ACTH-dependent Cushing's Syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cushing's syndrome (CS) comprises the clinical manifestations of exposure to elevated glucocorticoid hormones, either from exogenous sources or endogenous overproduction by the adrenal glands [1]. CS from endogenous production is rare with an incidence of 0.7 to 2.5 per million per year depending on the geographic region and population studied [2]. Although autonomous cortical adrenal adenomas or carcinomas are a cause of elevated cortisol, most cases (85 to 90%) are adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) dependent and are caused by corticotroph pituitary adenomas (Cushing's Disease or CD) [1]. The remaining ACTH-dependent cases mostly involve non-pituitary malignancies (Ectopic ACTH) which often are tumors of neuroendocrine origin such as small cell lung carcinoma or bronchial carcinoid [3, 4]. Here, we describe a case of Cushing's syndrome which initially appeared to be caused by ectopic ACTH secretion from metastatic small cell carcinoma. However, immunohistochemistry of the tumor cells was negative for ACTH expression, while corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) was strongly expressed, suggesting that the elevated ACTH levels were a result of pituitary secretion in response to CRH.

Case report

A 56 year old type 2 diabetic patient presented to the emergency room with shortness of breath. Review of systems revealed back pain for two weeks, without history of injury, and progressive generalized weakness and fatigue for many months. She also described constant right upper quadrant abdominal pain. On examination, there was hyperpigmentation of her face and neck in sun exposed areas, thin skin with violacious striae on her lower abdomen, and multiple ecchymoses over the extremities, abdomen and at venipuncture sites. There was prominent fat accumulation in the supraclavicular and dorsocervical regions. There also was objective evidence of proximal muscle weakness which, along with back pain, had caused her to be bed-ridden for two weeks. Her medications included an oral sulfonylurea for diabetes but no exogenous sources of corticosteroids. Laboratory results revealed hypokalemic alkalosis (K+ 2.1 mEq/l and HCO3 42 mEq/l). She was hyperglycemic (random glucose 339 mg/dl). An MRI of the spine showed multiple endplate compression fractures of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.

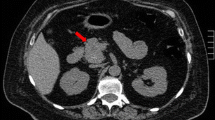

A clinical diagnosis of CS was suggested by the presentation. The laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Morning serum cortisol was extremely elevated and did not suppress after 1 mg Dexamethasone. The urinary cortisol was 16,575 μg/24 hours (normal 0-50 μg), which was confirmed on dilution. ACTH was elevated (278 pg/ml) in spite of hypercortisolism, confirming ACTH-dependent CS. A 48 hour high dose dexamethasone suppression test (2 mg every 6 hours for 8 doses) did not cause suppression of the serum cortisol suggesting that this was a case of ectopic ACTH and, in agreement, the pituitary gland had a normal appearance on MRI. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest did not reveal any lung nodules but did show mediastinal lymphadenopathy. CT abdomen showed multiple lesions in the liver and enlarged para-aortic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes suggestive of metastatic disease. The adrenal glands were prominent but were without focal nodularity.

Because no primary lesion was found on imaging, a number of follow-up laboratory tests were performed. Chromogranin A and Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were elevated consistent with a malignancy with neuroendocrine characteristics (Table 1). Laboratory tests for known causes of ectopic ACTH-namely, carcinoid (serotonin, 24 hour urine 5-hydroxy-indoleacteic acid), pheochromocytoma (plasma free metanephrines and normetanephrines), and medullary thyroid carcinoma (calcitonin)- were in the normal range (Table 1). Gastrin was over 2-fold higher than the upper limit of normal.

With the exception of the liver metastases and enlarged lymph nodes, there were no discrete lung nodules or neck, abdomen or pelvis lesions seen on CT. Scintigraphy with [111-In]pentreotide showed no tracer uptake at 4 hours. Specimens from bronchoalveolar lavage did not show any histologic findings of small cell lung carcinoma.

The patient's course continued to deteriorate, with hypokalemia, hyperglycemia and difficult to control blood pressure. She was started on ketoconazole, an inhibitor of cortisol synthesis, but her cortisol levels continued to escape inhibition after each dose escalation (Figure 1). The patient then was switched to metyrapone, resulting in a significant decrease in cortisol levels (Figure 1). Chemotherapy was initiated (cisplatin and vincristine) but the patient become hemodynamically unstable after one round of therapy and was transferred to the intensive care unit where she passed away. An autopsy was declined by the family which prevented confirmation of the origin of the small cell carcinoma.

Pathological findings

CT guided biopsy of one of the liver lesions was performed to obtain tissue for diagnosis. The biopsy consisted of multiple cores of soft tissue with no liver parenchyma present, although rare glandular structures were seen, suggestive of the residual bile ducts in the portal triad. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, there was extensive infiltration by small blue tumor cells surrounded by slender fibrous tissue (Figure 2). The cells were discohesive with small nucleoli, powdery chromatin, and no observable cytoplasm. The tumor cells were positive for neuroendocrine markers chromogranin, and synaptophysin as well as CD56 and Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 (TTF-1) (Figure 2). The cells were negative for the epithelial markers pancytokeratin and LC8 (CD45). These histopathologic findings were suggestive of small cell carcinoma. Surprisingly, immunostaining was negative for ACTH (Figure 2) (rabbit polyclonal antibody from Cell Marque, 1:200 dilution). Because of this, immunostaining for CRH was performed (rabbit polyclonal antibody from Sigma-Aldrich at a 1:200 dilution) which was strongly positive (Figure 2). Subsequently, a laboratory test for plasma CRH revealed that it was 10 pg/ml, at the upper limit of normal (0-10 pg/ml), in spite of concurrent hypercortisolism (Table 1).

Discussion

Cushing's syndrome (CS) is the clinical manifestations of cortisol overproduction from ACTH-independent (adrenal cortical adenoma or carcinoma) or ACTH-dependent mechanisms. Most ACTH-dependent CS is due to corticotroph pituitary adenomas (90%), while ectopic ACTH production only comprises around 10% of cases [4]. A significant proportion of ACTH-secreting neoplasms (7-19%) remain occult even after extensive investigation [4–6]. There have been few reports of ACTH producing tumors which co-secrete CRH and even fewer which describe ectopic CRH production in the absence of ACTH, as we suspect in this case. Overall, an extensive search of the literature revealed isolated CRH reported in 20 cases [7–17]. Medullary thyroid carcinoma (33%) and pheochromocytoma (19%) are the most prevalent among the cases of isolated ectopic-CRH, while carcinoid (5%) and small cell lung carcinoma (9.5%) are less common, different from ectopic ACTH cases, with the latter two as the most prevalent causes (Table 2)[7–17]. Interestingly, isolated CRH production from prostate cancer comprises 14% of the cases [9, 14] and yet it is an extremely rare source of ectopic ACTH (1-3%).There are single reports of sellar choristoma and gangliocytoma with isolated CRH production [9, 14].

We believe our patient had a CRH secreting tumor due to strongly positive CRH staining, negative ACTH staining, and detectable plasma CRH. A simple explanation for the lack of ACTH immunostaining is that it is not expressed in the tumor cells. The polyclonal antibody used for our ACTH immunostaining also reacts with the parent propeptide, pro-opiomelanocortin, so that aberrant prohormone processing of POMC to ACTH is not an explanation. We have not examined whether POMC transcripts were present in the biopsy sample, but there is precedence that POMC RNA can be present without detectable pro-peptide or ACTH in the tissue [7, 18]. In these cases, it is not clear whether the POMC transcripts are not properly translated, or the ACTH is secreted too soon after production to be stored [9]. In our patient, we only biopsied the metastatic lesions in the liver, so that we also cannot rule out that other non-hepatic metastatic lesions were able to produce ACTH.

An interesting aspect of this case is the lack of significant cortisol suppression by the high dose dexamethasone suppression test (HDDST; 2 mg dexamethasone every 6 hours for 48 hours), with baseline cortisol at 122.2 μg/dl before the test and 109 μg/dl after 48 hours. With isolated ectopic CRH, it is expected that CS develops through the stimulation of pituitary ACTH secretion with resultant adrenal cortisol production. Because of this, ACTH and cortisol levels potentially could suppress with HDDST, similar to a pituitary adenoma. Young and colleagues [19] reported this false positive suppression in a case of ectopic CRH-ACTH production, which also behaved like Cushing's disease by CRH stimulation testing and inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). However, in the case presented here as well as that of seven other ectopic CRH cases, the lack of suppression of ACTH and cortisol are consistent ectopic ACTH production, avoiding the superfluous performance of other, sometimes invasive, pituitary-centered procedures (e.g. IPSS) [3]. Similarly, a single dose of 8 mg dexamethasone (overnight) has not suppressed cortisol in cases of isolated ectopic CRH [12, 17]. These findings confirm that the positive drive by CRH can overwhelm the negative feedback by elevated corticosteroid. The systemic CRH levels in the case reported here were at the upper end of normal. Most other published cases of ectopic CRH reports do not have the CRH levels available for comparison.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of isolated ectopic CRH production from metastatic small cell carcinoma of unknown primary. From the literature, the tumors most commonly associated with ectopic CRH production are medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, and prostate cancer. With ectopic CRH syndrome, it is assumed that the pituitary is the source of ACTH with secretion driven by CRH overproduction. However, these tumors have behavior distinct from pituitary corticotroph adenomas, and the majority appears to lack suppression with high dose dexamethasone. Although the clinical presentation may be similar to ectopic ACTH syndrome, it is important to have ectopic CRH syndrome in the differential diagnosis for Cushing's syndrome.

Consent

The patient was deceased and attempts to contact the next of kin were not successful. Because of this, the case content was submitted to the Institutional Review Board and was determined to be exempt from IRB review.

Author details

Department of Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology, and Metabolism and Department of Pathology, One Baylor Plaza, Mail Stop 285, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, 77030.

References

Pivonello R, De Martino MC, De Leo M, Lombardi G, Colao A: Cushing's Syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008, 37: 135-49. 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.10.010. ix

Lindholm J, Juul S, Jorgensen JO, Astrup J, Bjerre P, Feldt-Rasmussen U: Incidence and late prognosis of cushing's syndrome: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86: 117-123. 10.1210/jc.86.1.117.

Vassiliadi D, Tsagarakis S: Unusual causes of Cushing's syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007, 51: 1245-1252.

Boscaro M, Arnaldi G: Approach to the patient with possible Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94: 3121-3131. 10.1210/jc.2009-0612.

Ilias I, Torpy DJ, Pacak K, Mullen N, Wesley RA, Nieman LK: Cushing's syndrome due to ectopic corticotropin secretion: twenty years' experience at the National Institutes of Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90: 4955-4962. 10.1210/jc.2004-2527.

Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Pozza C, Frajese V, Newell-Price J, Reznek RH: The ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 91: 371-377. 10.1210/jc.2005-1542.

Kristiansen MT, Rasmussen LM, Olsen N, Asa SL, Jorgensen JO: Ectopic ACTH syndrome: discrepancy between somatostatin receptor status in vivo and ex vivo, and between immunostaining and gene transcription for POMC and CRH. Horm Res. 2002, 57: 200-204. 10.1159/000058383.

Oates SK, Roth SI, Molitch ME: Corticotropin-releasing hormone-producing medullary thyroid carcinoma causing Cushing's syndrome: Clinical and pathological findings. Endocrine Pathology. 2000, 11: 277-285. 10.1385/EP:11:3:277.

Wajchenberg BL, Mendonca B, Liberman B, Adelaide M, Pereira A, Kirschner MA: Ectopic ACTH syndrome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1995, 53: 139-151. 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00044-Z.

Eng PH, Tan LH, Wong KS, Cheng CW, Fok AC, Khoo DH: Cushing's syndrome in a patient with a corticotropin-releasing hormone-producing pheochromocytoma. Endocr Pract. 1999, 5: 84-87.

Ruggeri RM, Ferrau F, Campenni A, Simone A, Barresi V, Giuffre G: Immunohistochemical localization and functional characterization of somatostatin receptor subtypes in a corticotropin releasing hormone- secreting adrenal phaeochromocytoma: review of the literature and report of a case. Eur J Histochem. 2009, 53: 1-6.

Chrisoulidou A, Pazaitou-Panayiotou K, Georgiou E, Boudina M, Kontogeorgos G, Iakovou I: Ectopic Cushing's syndrome due to CRH secreting liver metastasis in a patient with medullary thyroid carcinoma. Hormones (Athens). 2008, 7: 259-262.

Bayraktar F, Kebapcilar L, Kocdor MA, Asa SL, Yesil S, Canda S: Cushing's syndrome due to ectopic CRH secretion by adrenal pheochromocytoma accompanied by renal infarction. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006, 114: 444-447. 10.1055/s-2006-924154.

Saeger W, Reincke M, Scholz GH, Ludecke DK: Ectopic ACTH- or CRH-secreting tumors in Cushing's syndrome. Zentralbl Pathol. 1993, 139: 157-163.

Parenti G, Nassi R, Silvestri S, Bianchi S, Valeri A, Manca G: Multi-step approach in a complex case of Cushing's syndrome and medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006, 29: 177-181.

Jessop DS, Cunnah D, Millar JG, Neville E, Coates P, Doniach I: A phaeochromocytoma presenting with Cushing's syndrome associated with increased concentrations of circulating corticotrophin-releasing factor. J Endocrinol. 1987, 113: 133-138. 10.1677/joe.0.1130133.

Auchus RJ, Mastorakos G, Friedman TC, Chrousos GP: Corticotropin-releasing hormone production by a small cell carcinoma in a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 1994, 17: 447-452.

Smallridge RC, Bourne K, Pearson BW, Van Heerden JA, Carpenter PC, Young WF: Cushing's syndrome due to medullary thyroid carcinoma: diagnosis by proopiomelanocortin messenger ribonucleic acid in situ hybridization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88: 4565-4568. 10.1210/jc.2002-021796.

Young J, Deneux C, Grino M, Oliver C, Chanson P, Schaison G: Pitfall of petrosal sinus sampling in a Cushing's syndrome secondary to ectopic adrenocorticotropin-corticotropin releasing hormone (ACTH-CRH) secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998, 83: 305-308. 10.1210/jc.83.2.305.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. SS wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and analyzed the clinical data. HSK and RJN performed the immunohistochemistry on the biopsy samples and provided interpretation of the pathological findings. SLS coordinated the manuscript, edited the entire draft, performed the CRH immunostaining, and wrote the discussion of the case. RN edited the entire draft for final submission.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahani, S., Nudelman, R.J., Nalini, R. et al. Ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) syndrome from metastatic small cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol 5, 56 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-5-56

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-1596-5-56