Abstract

Background

Synthesis of patient-reported outcome (PRO) data is hindered by the range of available PRO measures (PROMs) composed of multiple scales and single items with differing terminology and content. The use of core outcome sets, an agreed minimum set of outcomes to be measured and reported in all trials of a specific condition, may improve this issue but methods to select core PRO domains from the many available PROMs are lacking. This study examines existing PROMs and describes methods to identify health domains to inform the development of a core outcome set, illustrated with an example.

Methods

Systematic literature searches identified validated PROMs from studies evaluating radical treatment for oesophageal cancer. PROM scale/single item names were recorded verbatim and the frequency of similar names/scales documented. PROM contents (scale components/single items) were examined for conceptual meaning by an expert clinician and methodologist and categorised into health domains. A patient advocate independently checked this categorisation.

Results

Searches identified 21 generic and disease-specific PROMs containing 116 scales and 32 single items with 94 different verbatim names. Identical names for scales were repeatedly used (for example, ‘physical function’ in six different measures) and others were similar (overlapping face validity) although component items were not always comparable. Based on methodological, clinical and patient expertise, 606 individual items were categorised into 32 health domains.

Conclusion

This study outlines a methodology for identifying candidate PRO domains from existing PROMs to inform a core outcome set to use in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Outcome selection and reporting in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) is often problematic. Heterogeneity in outcomes measured across studies in the same disease or treatment may hamper effective evidence synthesis. A systematic review of oesophageal studies, for example, found 10 different measures for postoperative mortality which were often undefined [1]. In addition, selective reporting of outcomes puts trials at risk of outcome reporting bias and can mean treatment effects are exaggerated [2]. These issues may be further complicated for patient reported outcomes (PROs). PROs are typically assessed using questionnaires (patient reported outcome measures (PROMs)) and many validated questionnaires are available because PROMs have been developed by different groups and disciplines (for example, clinical versus psychological) or for differing purposes (for example, measurement of health in generic populations versus disease-specific patient groups). A single PROM can be made up of numerous scales and single items and generic and disease specific PROMs are often combined to assess a range of relevant health domains within an RCT. This means that different (and often ill-defined) outcomes may be reported and the multiplicity of items and scales may also allow selection of statistically significant rather than pre-determined a priori PRO endpoints to be reported, increasing the risk of outcome reporting bias. Problems are further accentuated for PROs because terminology of the scales and items across PROMs is not universally agreed meaning data synthesis across studies is difficult when different questionnaires are used, and while there is overlap in the issues that are measured there is also variation because PROMs have been developed by different methods and for different purposes. Potential solutions to these challenges are to develop and use core outcome sets.

Core outcome sets (COSs) are an agreed minimum set of outcome domains to be measured and reported in all trials of a particular treatment or condition [3]. The routine measurement of COSs has the potential to facilitate data synthesis and reduce outcome reporting bias by standardising the outcomes that are measured across studies and this has been emphasised by the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative which supports the development and application of COSs for pragmatic (effectiveness) trials [4]. Pragmatic trials are designed to assess whether an intervention is effective for routine clinical practice and outcomes, therefore, need to be relevant and important to patients as well as clinicians and other key decision-makers [5]. In many cases these are the outcomes that are assessed with PROMs, particularly if the questionnaire has been developed with patient input [6] but the availability of so many different PROMs, however, means there are problems with selecting which of the measured health domains are ‘core’. The aim of this study, therefore, was to explore and report methods to identify PRO domains from the wealth of available PROMs and to use this approach to inform the development of a COS to use in pragmatic trials in a specific condition. Consensus on which outcomes to include in the final core set, and the methods to achieve this, are the focus of further research.

Methods

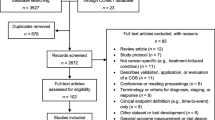

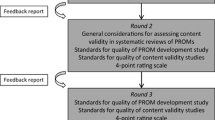

This study was undertaken within one disease site and treatment - radical treatment for oesophageal cancer, selected because the research team have clinical and PROM expertise in this area and have previously tried to summarise PRO evidence [7–9]. There were three phases of work: (1) a systematic literature review to identify validated PROMs used in oesophageal cancer studies and the scope of these instruments; (2) a detailed content analysis to explore PROM diversity; and (3) categorisation of PROM content into health domains (Figure 1).

Identification of PROMs used in oesophageal cancer studies

A systematic review was performed to identify and present the scope of existing validated PROMs in order to provide knowledge of the current of state of PRO measurement in this field.

Search strategy

Electronic searches in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and CINAHL databases between January 2006 and May 2011 were performed. The search strategy included terms for patient-reported outcomes, oesophageal cancer, surgery and chemotherapy, radiotherapy or combined therapy (see Additional file 1). Searches were limited to studies published in English language. Relevant studies published prior to 2006 were identified from a previous systematic review [8]. Abstracts of identified records were screened for inclusion and full text articles were assessed for eligibility by one of three reviewers (RW, MJ, RCM) with reasons for exclusion documented. No studies were excluded based on a risk of bias assessment or judgement of methodological quality because the purpose of the current study was to identify PROs rather than examine the quality of the data or treatment effect.

Selection criteria

Included were studies that used at least one validated PROM to evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQL) after radical treatment of oesophageal cancer, including surgical, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy interventions. Valid PROMs were defined as those that had been tested for psychometric validity and reliability in appropriate patient populations with methodology verified from published papers. No restrictions on study design or sample size were applied. Studies of palliative treatment, comparisons of clinician- or hospital-related factors, and those limited to investigating satisfaction with care or health utilities were excluded.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a pre-designed form, piloted before full data extraction with a sample of included studies. Study publication date, design and treatment intervention, the name of the PROM(s), the reported PRO scales and single items, and details of any additional non-validated questions were extracted. These were recorded by one reviewer (RM) and checked by additional members of the study team (MJ, MAGS). The validated PROMs were obtained, including other validated disease-specific PROMs known to authors. Verbatim names for the PRO scales and single items as termed by the PROM developers were extracted and all PROM items (scale components and any single items) were recorded. Data were stored in an electronic database.

Examination of PROM content

A detailed content analysis of the identified instruments was performed to explore the diversity of PROs in this field. Verbatim names for scales and single items were listed. Scales with identical names and others that were similar (defined as having a least one identical word) were documented, counted and compared for consistency and overlap of the component items.

Categorisation into health domains

To synthesise the existing content of instruments and provide a framework for future core set development, all PROM items (scale components and any single items) were examined and systematically categorised into conceptual health domains according to the issue they addressed. This was performed by expert methodologists (an oesophageal cancer surgeon and a psychologist) with experience of questionnaire development in health-related quality of life research and cancer (JMB and MAGS) based on their knowledge, familiarity and practiced skill of grouping questionnaire items in this field. Health domains were defined as generic aspects of quality of life affected by health or disease-specific issues and symptoms [10]. Further domains were defined until saturation, that is, all individual PROM items had been mapped onto a domain. Issues addressed in non-validated questions were additionally mapped to domains to verify that the conceptual health domains encompassed all outcomes measured in the included studies. Mapping of items to domains was checked for completeness and consistency by two authors (IK and RCM) and a patient advocate working within oncology research to maximise validity and reliability of the method. Variances were resolved by discussion within the study team and with the senior author (JMB). Data were recorded electronically.

Results

Identification of PROMs used in oesophageal cancer studies

A total of 1,351 records were screened for inclusion and 111 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 56 were excluded because they did not meet the criteria for eligibility, including seven studies that used PROMs without sufficient psychometric validation. Some 55 relevant articles reporting 56 studies were identified (Table 1) [11–65]. Almost all studies (n = 54, 96%) included data on PROs after surgery, either alone or with neoadjuvant chemo/radiotherapy. Nineteen validated PROMs were used (Table 1) [56, 66–83]: nine for gastrointestinal diseases, five cancer-specific instruments and five generic instruments. One oesophageal specific PROM was adapted from a cancer instrument (adapted Rotterdam Symptom Checklist). Three were earlier versions of an updated PROM (EORTC QLQ-C36, QLQ-OES24 and MOS SF20).The most frequently used PROMs were the EORTC QLQ-C30 (n = 34, 61%), and the disease-specific modules EORTC QLQ-OES18, or earlier version QLQ-OES24 (n = 27, 48%). PROMs were not always used in their entirety, with evidence of selective outcome reporting of scales and single items in 33 (59%), although there was variation across studies in the outcomes that were selected (data not shown). Twenty-one (37%) studies added an additional 74 non-validated items. A further two validated disease specific PROMs; the EORTC QLQ-OG25 [84] and EQOL[85], were sourced from authors’ knowledge, neither of which had been used in a published study since development and validation at the time of the conducted search (May 2011).

Examination of PROM content

There were 116 scales (composed from 574 individual items) and 32 single items in total, with 94 different verbatim scale/item names (Table 2). ‘Pain’ and ‘physical function’ were the most common verbatim name for a scale, used in six different PROMs, but other PROM scale names were also very similar (for example, physical wellbeing, physical problems, physical distress, physical activity, role physical) (Table 3). Some scales with identical names, however, had different component items. For example, ‘physical function’ in one PROM consisted of seven items relating to tiredness/fatigue, feeling unwell, waking up at night, changes in appearance, physical strength, endurance and feeling unfit [72], compared to ‘physical function’ in another PROM consisting of five items that referred to strenuous activity, ability to walk certain distances, time spent in bed or a chair, and need for help with self-care [74]. Similar heterogeneity was found for PROs assessed with single items, for example ‘cough’ in one PROM assessed waking at night because of coughing [67], whereas in another it was an assessment of coughing following eating [69]. While the two items assessed slightly different aspects of coughing they had the same name (‘cough’) and thus reporting would only refer to cough and not the actual issue being assessed within the item.

Categorisation into health domains

All PROM individual items (n = 606) were categorised into 32 conceptual generic or symptom specific domains by the study authors (Table 4). Illustrative examples of this categorisation process are provided for some of the generic health domains (Table 5). The most common assessed health domain (concept), that is, the health domain that most PROM items mapped to, was emotional function, assessed in 18 of the 21 PROMs. Other commonly assessed health domains were ‘pain/pain-related swallowing’ (assessed in 14 different PROMs), ‘physical activity/activities of daily life’ (in 13 PROMs) and ‘appetite/eating/taste’ (in 12 PROMs). Uncommon domains were ‘spiritual issues’ (assessed in one PROM) and ‘dizziness/dumping’ (assessed in two PROMs). Non-validated questions predominantly focused on eating and therefore were mapped onto the ‘appetite/eating/taste’ domain. A patient advocate checked the categorisation of items into health domains and there were no difference of opinion.

Discussion

This study comprehensively analysed PROs from studies in radical treatment for oesophageal cancer. Some 116 scales and 32 single items were identified from 21 validated PROMs. As many as 94 different verbatim names were used to describe PRO scales and single items and although many names were similar, content examination revealed component questions did not always address comparable issues. In-depth examination and categorisation of PROM contents concluded that together they addressed 32 different health domains demonstrating the vast overlap between PROMs.

Our findings show how evidence synthesis of oesophageal cancer PROs may be hampered because of the range of PROMs used in trials and the multiple scales and single items within them, often with inconsistent and non-transparent terminology. Core outcome sets aim to reduce this problem by identifying and prioritising the important health domains to be measured in all studies. The development of core outcome sets in other clinical areas has been undertaken using a range of methods, in particular the approach to including PROs [86–89]. In rheumatoid arthritis, for example, the initial American College of Rheumatology (ACR) core set was developed by a committee of experts (16 professionals in rheumatoid arthritis trials, health services research and biostatistics) who reviewed the literature on the validity of trial outcomes (for example, sensitivity to change or how well it predicted/correlated with a definite clinical change) and used a nominal group process to recommend and reach consensus on a list of core outcomes. The list was presented and finalised at a specialist international conference (OMERACT: Outcome Measures for Rheumatology in Clinical Trials) and contained both clinical and PROs, although patients were not involved in the consensus process. Outcomes were specific (for example, number of swollen joints) or more general domains (for example, functional status), with recommendations on how to measure the outcomes decided later [86]. Subsequent OMERACT conference discussions and workshops deliberately involved patients and led to the addition of fatigue in the ACR core set [87, 90], and continued work using interviews with patients, identified further important PROs [5]. This led to the development of a ‘patient core set’ of disease-specific and global outcome domains solely derived from patient opinion to complement the professional ACR core set [88]. Our current study methodology ensures that the patient perspective and relevant PROs inform the development of a core set of outcome domains from an early stage, because it examines the content of validated PROMs which are developed with significant patient involvement. The identified PRO domains will be prioritised using a Delphi method to reach consensus on the important to include in the core outcome set, alongside clinical outcomes [1], and is the focus of future work. Patients, surgeons and clinical nurse specialists will be surveyed to ensure the opinions of all key stakeholders are sought, a recommended approach by the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative [4].

This study included a detailed systematic search to identify PROs measured in oesophageal cancer studies and used rigourous methodology to identify health domains, however, it does have weaknesses. The categorisation of question items into health domains was performed by two experts and independently checked by other members of the research team, including a patient advocate, but it is possible that others may have categorised items differently. Inter-rater reliability statistics could have been recorded to describe agreement between the experts when categorising items. Future work therefore is needed to standardised and validate this method. In addition, presentation of the methodology to a greater number of patients or patient representatives could strengthen the robustness and reliability of the categorisation process.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates there is diversity in the PROMs selected to evaluate radical treatment for oesophageal cancer. Within and between PROMs there is a lack of clarity between named scales and items and the underlying health domains being assessed meaning data synthesis is limited. A methodology for identifying important PRO health domains is proposed which can be used to inform the development of a core set of health domains. Following this it will be necessary to determine accurate and efficient ways to measure these core domains, drawing on items banks developed by initiatives such as PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) and COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement Instruments) [91, 92].

Abbreviations

- COS:

-

Core outcome set

- HRQL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- PRO:

-

Patient-reported outcome

- PROM:

-

Patient-reported outcome measure

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial.

References

Blencowe NS, Strong S, McNair AGK, Brookes ST, Crosby T, Griffin SM, Blazeby JM: Reporting of short-term clinical outcomes after esophagectomy: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012, 255: 658-666. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182480a6a.

Dwan K, Altman DG, Arnaiz JA, Bloom J, Chan AW, Cronin E, Decullier E, Easterbrook PJ, Von Elm E, Gamble C, Ghersi D, Ioannidis JP, Simes J, Williamson PR: Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. Plos One. 2008, 3: e3081-10.1371/journal.pone.0003081.

Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, Tugwell P: Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012, 13: 132-10.1186/1745-6215-13-132.

COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative.http://www.comet-initiative.org/,

Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S: What outcomes from pharmacologic treatments are important to people with rheumatoid arthritis? Creating the basis of a patient core set. Arthrit Care Res. 2010, 62: 640-646. 10.1002/acr.20034.

US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration: Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009,http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf,

Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Blazeby JMKI, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Haes HC, Smets EM, Sprangers MA: Systematic review reveals limitations of studies evaluating health-related quality of life after potentially curative treatment for esophageal cancer. Qual Life Res. 2012, 22: 1787-1803.

Parameswaran R, McNair A, Avery KNL, Berrisford RG, Wajed SA, Sprangers MAG, Blazeby JM: The role of health-related quality of life outcomes in clinical decision making in surgery for esophageal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008, 15: 2372-2379. 10.1245/s10434-008-0042-8.

Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Elbers RG, Sitnikova K, Korfage IJ, Smets EM, Henselmans I, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Haes JC, Blazeby JM, Sprangers MA: Meta-analysis shows clinically relevant and long-lasting deterioration in health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. Qual Life Res. 2013, [Epub ahead of print]

Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL: Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993, 118: 622-629. 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009.

Ariga H, Nemoto K, Miyazaki S, Yoshioka T, Ogawa Y, Sakayauchi T, Jingu K, Miyata G, Onodera K, Ichikawa H, Kamei T, Kato S, Ishioka C, Satomi S, Yamada S: Prospective comparison of surgery alone and chemoradiotherapy with selective surgery in resectable squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2009, 75: 348-356. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.086.

Avery KNL, Metcalfe C, Barham CP, Alderson D, Falk SJ, Blazeby JM: Quality of life during potentially curative treatment for locally advanced oesophageal cancer. British J Surg. 2007, 94: 1369-1376. 10.1002/bjs.5888.

Barbour AP, Lagergren P, Hughes R, Alderson D, Barham CP, Blazeby JM: Health-related quality of life among patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction treated by gastrectomy or oesophagectomy. Brit J Surg. 2008, 95: 80-84.

Blazeby JM, Farndon JR, Donovan J, Alderson D: A prospective longitudinal study examining the quality of life of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000, 88: 1781-1787. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1781::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-G.

Blazeby JM, Sanford E, Falk SJ, Alderson D, Donovan JL: Health-related quality of life during neoadjuvant treatment and surgery for localized esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005, 103: 1791-1799. 10.1002/cncr.20980.

Blazeby JM, Williams MH, Brookes ST, Alderson D, Farndon JR: Quality-of-lifemeasurement in patients with esophageal cancer. Gut. 1995, 37: 505-508. 10.1136/gut.37.4.505.

Brooks JA, Kesler KA, Johnson CS, Ciaccia D, Brown JW: Prospective analysis of quality of life after surgical resection for esophageal cancer: Preliminary results. J Surg Oncol. 2002, 81: 185-194. 10.1002/jso.10175.

Cense HA, Visser MRM, Van Sandick JW, de Boer AGEM, Lamme B, Obertop H, Van Lanschot JJB: Quality of life after colon interposition by necessity for esophageal cancer replacement. J Surg Oncol. 2004, 88: 32-38. 10.1002/jso.20132.

Chang LC, Oelschlager BK, Quiroga E, Parra JD, Mulligan M, Wood DE, Pellegrini CA: Long-term outcome of esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia or cancer found during surveillance for Barrett's esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006, 10: 341-346. 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.12.007.

de Boer AGEM, Genovesi PIO, Sprangers MAG, van Sandick JW, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJB: Quality of life in long-term survivors after curative transhiatal oesophagectomy for oesophageal carcinoma. Brit J Surg. 2000, 87: 1716-1721. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01600.x.

de Boer AGEM, van Lanschot JJB, van Sandick JW, Hulscher JBF, Stalmeier PFM, de Haes JCJM, Tilanus HW, Obertop H, Sprangers MAG: Quality of life after transhiatal compared with extended transthoracic resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 4202-4208. 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.102.

Djarv T, Lagergren J, Blazeby JM, Lagergren P: Long-term health-related quality of life following surgery for oesophageal cancer. Brit J Surg. 2008, 95: 1121-1126. 10.1002/bjs.6293.

Egberts JH, Schniewind B, Bestmann B, Schafmayer C, Egberts F, Faendrich F, Kuechler T, Tepel J: Impact of the site of anastomosis after oncologic esophagectomy on quality of life - A prospective, longitudinal outcome study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008, 15: 566-575. 10.1245/s10434-007-9615-1.

Gillham CM, Aherne N, Rowley S, Moore J, Hollywood D, O'Byrne K, Reynolds JV: Quality of life and survival in patients treated with radical chemoradiation alone for oesophageal cancer. Clin Oncol-Uk. 2008, 20: 227-233. 10.1016/j.clon.2007.12.002.

Gockel I, Gonner U, Domeyer M, Lang H, Junginger T: Long-term survivors of esophageal cancer: disease-specific quality of life, general health and complications. J Surg Oncol. 2010, 102: 516-522.

Gradauskas P, Rubikas R, Saferis V: Changes in quality of life after esophageal resections for carcinoma. Medicina. 2006, 42: 187-194.

Hallas CN, Patel N, Oo A, Jackson M, Murphy P, Drakeley MJ, Soorae A, Page RD: Five-year survival following oesophageal cancer resection: psychosocial functioning and quality of life. Psychol Health Med. 2001, 6: 85-94. 10.1080/13548500124671.

Headrick JR, Nichols FC, Miller DL, Allen MS, Trastek VF, Deschamps C, Schleck CD, Thompson AM, Pairolero PC: High-grade esophageal dysplasia: long-term survival and quality of life after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002, 73: 1697-1702. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03496-3.

Higuchi A, Minamide J, Ota Y, Takada K, Aoyama N: Evaluation of the quality of life after surgical treatment for thoracic esophageal cancer. Esophagus. 2006, 3: 53-59. 10.1007/s10388-006-0078-4.

Hurmuzlu M, Aarstad HJ, Aarstad AKH, Hjermstad MJ, Viste A: Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors after high-dose chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery in esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2011, 24: 39-47. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2010.01104.x.

Lagergren P, Avery KNL, Hughes R, Barham CP, Alderson D, Falk SJ, Blazeby JM: Health-related quality of life among patients cured by surgery for esophageal cancer. Cancer-Am Cancer Soc. 2007, 110: 686-693.

Leibman S, Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas J: Minimally invasive esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2006, 20: 428-433. 10.1007/s00464-005-0388-y.

Luketich JD, Alvelo-Rivera M, Buenaventura PO, Christie NA, McCaughan JS, Litle VR, Schauer PR, Close JM, Fernando HC: Minimally invasive esophagectomy - outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg. 2003, 238: 486-494.

Martin L, Lagergren J, Lindblad M, Rouvelas I, Lagergren P: Malnutrition after oesophageal cancer surgery in Sweden. Brit J Surg. 2007, 94: 1496-1500. 10.1002/bjs.5881.

McLarty AJ, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Allen MS, Pairolero PC, Harmsen WS: Esophageal resection for cancer of the esophagus: long-term function and quality of life. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997, 63: 1568-1572. 10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00125-2.

Moraca RJ, Low DE: Outcomes and health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal cancer. Arch Surg-Chicago. 2006, 141: 545-549. 10.1001/archsurg.141.6.545.

Nakamura M, Kido Y, Hosoya Y, Yano M, Nagai H, Monden M: Postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction after 2-field versus 3-field lymph node dissection in patients with esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2007, 37: 379-382. 10.1007/s00595-006-3413-4.

Ohanlon DM, Harkin M, Karat D, Sergeant T, Hayes N, Griffin SM: Quality-of-life assessment in patients undergoing treatment for esophageal-carcinoma. Brit J Surg. 1995, 82: 1682-1685. 10.1002/bjs.1800821232.

Olsen MF, Larsson M, Hammerlid E, Lundell L: Physical function and quality of life after thoracoabdominal oesophageal resection - results of a longitudinal follow-up study. Digest Surg. 2005, 22: 63-68. 10.1159/000085348.

Parameswaran R, Blazeby JM, Hughes R, Mitchell K, Berrisford RG, Wajed SA: Health-related quality of life after minimally invasive oesophagectomy. Brit J Surg. 2010, 97: 525-531. 10.1002/bjs.6908.

Reynolds JV, McLaughlin R, Moore J, Rowley S, Ravi N, Byrne PJ: Prospective evaluation of quality of life in patients with localized oesophageal cancer treated by multimodality therapy or surgery alone. Brit J Surg. 2006, 93: 1084-1090. 10.1002/bjs.5373.

Rosmolen WD, Boer KR, de Leeuw RJR, Gamel CJ, Henegouwen MIV, Bergman JJGHM, Sprangers MAG: Quality of life and fear of cancer recurrence after endoscopic and surgical treatment for early neoplasia in Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2010, 42: 525-531. 10.1055/s-0029-1244222.

Rutegard M, Lagergren J, Ronvelas I, Lindblad M, Blazeby JM, Lagergren P: Population-based study of surgical factors in relation to health-related quality of life after oesophageal cancer resection. Brit J Surg. 2008, 95: 592-601. 10.1002/bjs.6021.

Safieddine N, Xu W, Quadri SM, Knox JJ, Hornby J, Sulman J, Wong R, Guindi M, Keshavjee S, Darling G: Health-related quality of life in esophageal cancer: effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgical intervention. J Thorac Cardiov Sur. 2009, 137: 36-42. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.049.

Schembre D, Arai A, Levy S, Farrell-Ross M, Low D: Quality of life after esophagectomy and endoscopic therapy for Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. Dis Esophagus. 2010, 23: 458-464. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01042.x.

Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Schmid A, Kremer B: Quality of life associated with surgery for esophageal cancer: differences between collar and intrathoracic anastomoses. World J Surg. 2004, 28: 355-360. 10.1007/s00268-003-7219-x.

Schneider L, Hartwig W, Aulmann S, Lenzen C, Strobel O, Fritz S, Hackert T, Keller M, Buehler MW, Werner J: Quality of life after emergency vs. elective esophagectomy with cervical reconstruction. Scand J Surg. 2010, 99: 3-8.

Servagi-Vernat S, Bosset M, Crehange G, Buffet-Miny J, Puyraveau M, Maingon P, Mercier M, Bosset JF: Feasibility of chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal cancer in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years. A prospective, single-arm Phase II study. Drug Aging. 2009, 26: 255-262. 10.2165/00002512-200926030-00006.

Spector NM, Hicks FD, Pickleman J: Quality of life and symptoms after surgery for gastroesophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2002, 25: 120-125. 10.1097/00001610-200205000-00007.

Staal EFWC, van Sandick JW, van Tinteren H, Cats A, Aaronson NK: Health-related quality of life in long-term esophageal cancer survivors after potentially curative treatment. J Thorac Cardiov Sur. 2010, 140: 777-783. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.05.018.

Stein HJ, Feith M, Mueller J, Werner M, Siewert JR: Limited resection for early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Surg. 2000, 232: 733-740. 10.1097/00000658-200012000-00002.

Sweed MR, Schiech L, Barsevick A, Babb JS, Goldberg M: Quality of life after esophagectomy for cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002, 29: 1127-1131. 10.1188/02.ONF.1127-1131.

Tan QY, Wang RW, Jiang YG, Fan SZ, Hsin MKY, Gong TQ, Zhou JH, Zhao YP: Lung volume reduction surgery allows esophageal tumor resection in selected esophageal carcinoma with severe emphysema. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006, 82: 1849-1856. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.081.

Teoh AYB, Chiu PWY, Wong TCL, Liu SYW, Wong SKH, Ng EKW: Functional performance and quality of life in patients with squamous esophageal carcinoma receiving surgery or chemoradiation. Results from a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2011, 253: 1-5. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fcd991.

Van Meerten E, Van Der Gaast A, Looman CWN, Tilanus HWG, Muller K, Essink-Bot ML: Quality of life during neoadjuvant treatment and after surgery for resectable esophageal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2008, 71: 160-166. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.038.

Vanknippenberg FCE, Out JJ, Tilanus HW, Mud HJ, Hop WCJ, Verhage F: Quality of life in patients with resected esophageal cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1992, 35: 139-145. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90161-I.

Verschuur EML, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Essink-Bot ML, Tran KTC, Van der Gaast A, Tilanus HW, Siersema PD: Experiences and expectations of patients after oesophageal cancer surgery: an explorative study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006, 15: 324-332. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00659.x.

Viklund P, Lindblad M, Lagergren J: Influence of surgery-related factors on quality of life after esophageal or cardia cancer resection. World J Surg. 2005, 29: 841-848. 10.1007/s00268-005-7887-9.

Viklund P, Wengstrom Y, Rouvelas I, Lindblad M, Lagergren J: Quality of life and persisting symptoms after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur J Cancer. 2006, 42: 1407-1414. 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.02.005.

Wang H, Feng MX, Tan LJ, Wang Q: Comparison of the short-term quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer after subtotal esophagectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic or open surgery. Dis Esophagus. 2010, 23: 408-414.

Wang H, Tan LJ, Feng MX, Zhang Y, Wang Q: Comparison of the short-term health-related quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer with different routes of gastric tube reconstruction after minimally invasive esophagectomy. Qual Life Res. 2011, 20: 179-189. 10.1007/s11136-010-9742-1.

Yamashita H, Okuma K, Seto Y, Mori K, Kobayashi S, Wakui R, Ohtomo K, Nakagawa K: A retrospective comparison of clinical outcomes and quality of life measures between definitive chemoradiation alone and radical surgery for clinical stage II-III esophageal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2009, 100: 435-441. 10.1002/jso.21361.

Zhang C, Wu QC, Hou PY, Zhang M, Li QA, Jiang YJ, Chen D: Impact of the method of reconstruction after oncologic oesophagectomy on quality of life - a prospective, randomised study. Eur J Cardio-Thorac. 2011, 39: 109-114. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.032.

Zieren HU, Jacobi CA, Zieren J, Muller JM: Quality of life following resection of oesophageal carcinoma. Brit J Surg. 1996, 83: 1772-1775. 10.1002/bjs.1800831235.

Zieren HU, Muller JM, Jacobi CA, Pichlmaier J, Muller RP, Staar S: Adjuvant postoperative radiation-therapy after curative resection of squamous-cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus - a prospective randomized study. World J Surg. 1995, 19: 444-449. 10.1007/BF00299187.

Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Hammerlid E, Fayers P, Sezer O, Koller M, Arraras J, Bottomley A, Vickery CW, Etienne PL, Alderson D: Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003, 39: 1384-1394. 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00270-3.

Darling G, Eton DT, Sulman J, Casson AG, Cella D: Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006, 107: 854-863. 10.1002/cncr.22055.

Velanovich V: The development of the GERD-HRQL symptom severity instrument. Dis Esophagus. 2007, 20: 130-134. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00658.x.

Hicks FD, Spector NM: The life after gastric surgery index: conceptual basis and initial psychometric assessment. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2004, 27: 50-54. 10.1097/00001610-200403000-00003.

Nakamura M, Kido Y, Egawa T: Development of a 32-item scale to assess postoperative dysfunction after upper gastrointestinal cancer Resection. J Clin Nurs. 2008, 17: 1440-1449. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02179.x.

Blazeby JM, Alderson D, Winstone K, Steyn R, Hammerlid E, Arraras J, Farndon JR: Development of an EORTC questionnaire module to be used in quality of life assessment for patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1996, 32A: 1912-1917.

Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wooddauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H: Gastrointestinal quality of life index - development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995, 82: 216-222. 10.1002/bjs.1800820229.

De Haes JCJM, Vanknippenberg FCE, Neijt JP: Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients - structure and application of the Rotterdam symptom checklist. Br J Cancer. 1990, 62: 1034-1038. 10.1038/bjc.1990.434.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Dehaes JCJM, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F: The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 - a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85: 365-376. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365.

Osse BHP, Vernooij M, Schade E, Grol R: Towards a new clinical tool for needs assessment in the palliative care of cancer patients: The PNPC instrument. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004, 28: 329-341. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.01.010.

Northouse LL: Mastectomy patients and the fear of cancer recurrence. Cancer Nurs. 1981, 4: 213-220.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983, 67: 361-370. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Derogatis LR: The psychosocial adjustment to illness scales (PAIS). J Psychosom Res. 1986, 30: 77-91. 10.1016/0022-3999(86)90069-3.

Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE: The MOS Short-form general health survery - reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988, 26: 724-732. 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007.

Shacham S: A shortened version of the Profile of Mood States. J Pers Assess. 1983, 47: 305-306. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36).1. Conceptual-framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992, 30: 473-483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002.

Aaronson N, Ahmedzai S, Bullinger M: The EORTC core quality of life questinnaire:interim results of an international field study. Effect of cancer on quality of life. Edited by: Osoba D. 1991, Boca Raton FL: CRC Press Ltd

de Boer A, Genovesi PIO, Sprangers MAG, van Sandick JW, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJB: Quality of life in long-term survivors after curative transhiatal oesophagectomy for oesophageal carcinoma. British J Surg. 2000, 87: 1716-1721. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01600.x.

Lagergren P, Fayers P, Conroy T, Stein HJ, Sezer O, Hardwick R, Hammerlid E, Bottomley A, Van Cutsem E, Blazeby JM, European Organisation Res T: Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43: 2066-2073. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.005.

Clifton JC, Finley RJ, Gelfand G, Graham AJ, Inculet R, Malthaner R, Tan L, Lim J, Singer J, Lovato C: Development and validation of a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire (EQOL) for potentially curable patients with carcinoma of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2007, 20: 191-201. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00669.x.

Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Chernoff M, Fried B, Furst D, Goldsmith C, Kieszak S, Lightfoot R, Paulus H, Tugwell P, Weinblatt M, Widmark R, Williams J, Wolfe F: The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 1993, 36: 729-740. 10.1002/art.1780360601.

Kirwan JR, Hewlett SE, Heiberg T, Hughes RA, Carr M, Hehir M, Kvien TK, Minnock P, Newman SP, Quest EM, Taal E, Wale J: Incorporating the patient perspective into outcome assessment in rheumatoid arthritis–progress at OMERACT 7. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 2250-2256.

Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, Richards P, Hewlett S: Patient perspective of measuring treatment efficacy: the rheumatoid arthritis patient priorities for pharmacologic interventions outcomes. Arthrit Care Res. 2010, 62: 647-656.

Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR: Using the Delphi Technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. Plos Medicine. 2011, 8: 8-

Kirwan JR, Minnock P, Adebajo A, Bresnhan B, Choy E, de Wit M, Hazes M, Richards P, Saag K, Suarez-Almazor M, Wells G, Hewlett S: Patient perspective: fatigue as a recommended patient centered outcome measure in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007, 34: 1174-1177.

Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M; PROMIS Cooperative Group: The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007, 45: S3-S11.

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RWJG, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW: Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res. 2012, 21: 651-657. 10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council Network of Hubs for Trials Methodology Research (ConDuCT Hub - Collaboration and iNnovation in DifficUlt and complex randomised Controlled Trials - G0800800) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Patient Benefit Program PB-PG- 0807–14131. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

The authors thank Mrs Jackie Elliott, representative of the Gastro/Oesophageal Support & Help (GOSH) group, Bristol, for checking the categorisation of items.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RM conducted and coordinated the review and drafted the manuscript. MJ was involved in the systematic databases searches, data extraction and contributed to the draft manuscript. IK and JN contributed to the systematic search for studies. RW helped to screen abstracts for the review. ST contributed to the design of the study. MS checked the data extraction, grouped data into PRO domains and contributed to the draft manuscript. JB conceived the idea for the review, was involved in the design of the study and data extraction, grouped data into PRO domains, contributed to the draft manuscript and supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Macefield, R.C., Jacobs, M., Korfage, I.J. et al. Developing core outcomes sets: methods for identifying and including patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Trials 15, 49 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-49

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-49