Abstract

Background

Use of inappropriate drugs is common among institutionalized older people. Rigorous trials investigating the effect of the education of staff in institutionalized settings on the harm related to older people’s drug treatment are still scarce. The aim of this trial is to investigate whether training professionals in assisted living facilities reduces the use of inappropriate drugs among residents and has an effect on residents’ quality of life and use of health services.

Methods and design

During years 2011 and 2012, a sample of residents in assisted living facilities in Helsinki (approximately 212) will be recruited, having offered to participate in a trial aiming to reduce their harmful drugs. Their wards will be randomized into two arms: one, those in which staff will be trained in two half-day sessions, including case studies to identify inappropriate, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs among their residents, and two, a control group with usual care procedures and delayed training. The intervention wards will have an appointed nurse who will be responsible for taking care of the medication of the residents on her ward, and taking any problems to the consulting doctor, who will be responsible for the overall care of the patient. The trial will last for twelve months, the assessment time points will be zero, six and twelve months.

The primary outcomes will be the proportion of persons using inappropriate, anticholinergic, or more than two psychotropic drugs, and the change in the mean number of inappropriate, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs among residents. Secondary endpoints will be, for example, the change in the mean number of drugs, the proportion of residents having significant drug-drug interactions, residents' health-related quality of life (HRQOL) according to the 15D instrument, cognition according to verbal fluency and clock-drawing tests and the use and cost of health services, especially hospitalizations.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale randomized trial exploring whether relatively light intervention, that is, staff training, will have an effect on reducing harmful drugs and improving QOL among institutionalized older people.

Trial registration

ACTRN12611001078943

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Polypharmacy and use of inappropriate drugs is very common among frail institutionalized residents[1–3]. Older people living in nursing homes and institutions are administered an average eight to ten medications[2, 4]. Polypharmacy is a challenge for clinicians, because it is associated with a risk of drug-drug interactions and adverse effects[5]. In institutional settings, polypharmacy has been defined as using more than eight drugs[6], or ten or more drugs[7].

Inappropriate medications for older people have been defined in several different ways[8–11]. The criteria may be explicit, that is, drug- or disease-oriented, implemented to all patients in a similar way, and thus, simple to use[12]. The criteria may be also implicit, that is, based on clinical judgment; they may include more complicated domains such as effectiveness, drug-drug interactions, lowest cost or duplications. These kinds of criteria are more comprehensive, but also more complicated to use[12]. The most widely used international explicit criteria have been developed by Beers’ expert panel[8, 9]. Of Finnish elderly residents in institutional care, 36% were on the Beers’ list of inappropriate drugs[1, 13]. This proportion is similar or lower than those found in respective American or Australian studies[14, 15]. Use of inappropriate medications may not increase mortality, but it may result in unnecessary hospitalizations[16].

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 in the USA succeeded in decreasing the use of harmful psychiatric medications among older people[17]. There have been warnings concerning the use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia, with an increased risk of stroke and mortality[18, 19]. The use of psychotropic drugs is associated with risk of falls[20]. There is extensive use of psychotropic drugs in Finnish nursing homes, 80% being administered at least one psychotropic drug[4].

There is also increasing evidence of the adverse effects of drugs with anticholinergic properties. In addition to the traditional side effects such as dryness of mouth, constipation and worsening glaucoma, they have been shown to be associated with cognitive decline[21, 22], and they may increase the risk of hospital admissions[23]. They may be particularly harmful for older people with cognitive decline and dementia, such as for those in institutional care. In recent studies, particular attention has been paid to the use of anticholinergic drugs and defining them[22, 24].

The criteria of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen) for inappropriate drugs for older people include also the long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and tramadol[7]. There is also increasing evidence that long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) among frail elderly institutionalized residents is associated with infections, hip fractures and even higher mortality[25].

Drug-drug interactions are of concern and they are associated with adverse events[26]. Swedish Finnish INteraction X-referencing (SFINX) is a commercial medical interaction database that includes information on >6200 drug-drug interactions and it is updated quarterly by specialists in clinical pharmacology[27]. The potential drug-drug interactions in the SFINX database are classified according to their clinical significance and level of documentation. Clinical significance is classified from A to D, where A means the interaction is clinically insignificant and D means the interaction is clinically significant and the combination should be avoided[26].

At least 20 randomized controlled studies have been performed aiming to reduce the use of potentially inappropriate drugs among older people living in nursing homes. However, most studies have been of low quality, and thus, have risk of bias[28]. According to a recent systematic review, interventions using educational outreach, on-site education and pharmacist medication reviews may reduce inappropriate drug use[28]. Successful educational interventions have been performed to decrease the use of psychotropic medications for institutionalized elderly patients[29–33] and to improve the quality of drug prescribing[34, 35]. However, only a few studies have explored the intervention effects on older people’s well-being or their use of health services.

The aim of this study is to determine whether training nurses in assisted living facilities in Helsinki would reduce the use of inappropriate medications, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs among the residents in these houses. In addition, we will examine the effect of intervention on quality of life (QOL), cognition, and use and costs of health services of the participating older people.

Methods

General design

The study is a randomized controlled trial in which wards in assisted living facilities in Helsinki are randomly allocated to two arms. The staff in intervention wards will receive two half-day training sessions concerning appropriate use of drugs among frail older people. Approximately 212 patients will be included: 100 subjects in the intervention group and 100 in the control group. The number of patients per group may vary, because the wards randomized may vary in size. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital. Informed consent has been obtained from each patient and/or their closest proxy before any study procedure is performed according to good clinical practice.

Participants

Older residents residing in assisted living facilities in Helsinki will be recruited one by one by approaching them and their closest proxy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for residents in assisted living facilities:

-

65 years or older, living permanently in assisted living facilities in Helsinki

-

a native speaker of the Finnish language

-

uses at least one drug

-

no terminal illness (estimated prognosis >6 months), and

-

voluntary participation, written informed consent to participate in the study given by participant or her/his closest proxy.

Those residents fulfilling the inclusion criteria are invited for the first study nurse visit. In case of the participants’ cognitive decline (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) <20)[36] or poor judgment capability, the proxy is invited to give consent in addition to the participant.

Study procedures

The baseline study visit lasts about one hour and includes an interview to ascertain residents’ demographic data, diagnoses, and medications used. The diagnoses and medications are confirmed from medical records.

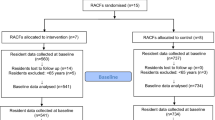

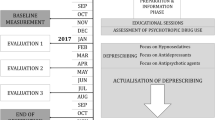

The participant will be assessed using the clinical dementia rating scale (CDR)[37], Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)[36], verbal fluency[38, 39], the clock-drawing test[40], and Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA)[41]. Patients’ psychological well-being will be assessed using the psychological well-being (PWB) scale[42] and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) will be assessed by 15D measure[43]. Participants will be assessed by two study nurses three times during the year: at baseline, and at six and twelve months. The flow chart of the study is presented in Figure1, and study assessment procedures are described in Table1. Hospitalizations, use of other health and social services and death dates will be retrieved from the central registers for one year from baseline measurements.

Drug use will be assessed as the point prevalence on the day of assessment. Residents will be classified as regular drug users if their medical charts indicate a regular sequence of administration on a daily basis. Additional analyses will be performed including both regularly used drugs as well as drugs used on a pro re nata (prn, or as needed) basis. The drugs administered to residents will be classified according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)[44]. The drugs that will be considered as inappropriate, having anticholinergic properties or being psychotropic drugs are presented in Additional file1: Table S1. The total number of these drugs each resident is using one, on a regular daily basis and two, both regularly or prn will be counted.

We randomized wards instead of individual participants in order to avoid contamination. The wards selected for this study were all using the Minimum Data Set (MDS)/Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) version 2.0 for home care[45]. MDS is used for assessing the residents’ needs and for individual care planning purposes. Each nurse has been educated to use MDS, and the assessment is routinely performed twice annually or whenever there is a substantial change in the resident’s status. In addition to the internationally well-validated scales and items, MDS provides a patient’s ward profile, often called ‘the case-mix’ (for example, ‘psychogeriatric’, ‘physically disabled’ or ‘cognitively impaired’), and gives the mean level of residents’ need for assistance. After identifying the case-mix in each of the wards, the wards will be divided into dyads having approximately the same characteristics. These dyads will be further randomized, by means of computer-generated random numbers, into two arms: those to receive staff training or to receive education after the trial. In addition, individual RAI items (for example, the proportion of fallers) and some of the well-validated RAI scale items (for example, neuropsychiatric symptoms, symptoms of delirium) will be used in measuring the effects of intervention.

Intervention

In intervention wards, the nurses and consultant physician, if available, will receive training with emphasis on drug safety, inappropriate drugs for older people, drugs with anticholinergic properties, problems related to psychotropic drugs and the adverse effects related to NSAIDs and PPIs. D-class interactions of drugs will be discussed. We will also give information in these educational sessions about evidence-based treatments in this patient group. The training will be organized as an activating discussion session separately for each intervention ward. Cases related to their own residents will be discussed. Two educational sessions per ward will be organized. In addition, nurses responsible for pharmaceuticals will be provided with more intensive training, together with others responsible for drugs, regarding procedures and processes of how to reduce drug use. A list of inappropriate drugs will be provided to all nurses working in intervention wards. In addition, for each intervention ward a nurse responsible for drugs will be appointed. She/he will bring potential drug problems to the consulting physician in assisted living. In institutions, assisted living facilities and nursing homes in Helsinki, physicians act as visiting consultants to whom the nurses take problematic cases. The physician will take the final responsibility to change or to continue the drugs.

The control wards will continue with the usual care processes. The staff in these wards will receive training in drug treatment after the study is over.

Outcome measurements

The research nurses perform their assessments at zero, six and twelve months.

Primary outcome measures are:

-

the proportion of persons using inappropriate, anticholinergic or more than two psychotropic drugs (these drugs are presented in Additional file1: Table S1), and

-

the change in the mean number of inappropriate, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs.

Secondary outcome measures are:

-

change in the mean WHO-defined daily dose[44] of inappropriate, anticholinergic or psychotropic drugs

-

the proportion of persons with significant drug-drug interactions according to SFINX[27]

-

the number of drug-related problems[46]

-

change in the mean number of drugs

-

change in the proportion of participants having nine or more drugs

-

use of health care services and their costs during a 12-month follow-up

-

the number of hospitalizations/follow-up time

-

the 15D HRQOL measure[43]

-

cognition according to verbal fluency and clock-drawing test[38–40], and CDR sum of boxes[37]

-

change in neuropsychiatric symptoms or symptoms of delirium according to the RAI instrument[45], and

-

the number of fallers according to the RAI instrument[45].

Statistical analyses

Required sample size calculation is based upon the change in the proportion of users of inappropriate, anticholinergic or psychotropic drugs. Sample size was calculated as follows: if in the control group 36% use inappropriate drugs, the minimum group difference with the assessment is 20%, type I error 5%, power 80%, which results in 106/group. Because we recruit participants from wards and aim to include as many as possible from those wards, the final sample size may differ slightly from this figure.

In these baseline findings, for the continuous variables, descriptive values will be expressed by means with standard deviations (SD) and medians with range. For the variables with a normal (Gaussian) distribution, statistical comparisons between the groups will be made by using a t test. If the variables have a non-normal distribution or ordinal level, statistical comparison between groups will be performed with the Mann Whitney U test. Measures with a discrete distribution will be expressed as percentages (%) and analyzed by X 2 or Fischer’s exact test when appropriate.

The results will be analyzed according to intention to treat. For imputation method, ‘the last observation carried forward’ (LOCF) and ‘worst-rank score’ principle will be used. For the most important outcome parameters, estimation of confidence interval (95%) will be used in addition to testing. Since the distributions of health care costs are highly skewed, the differences between means and confidence intervals are estimated using the bootstrap method (bias corrected and accelerated bootstrapping).

Discussion

This rigorous randomized trial will test whether a relatively light educational intervention will have an effect on the use of inappropriate, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs use among frail older residents in assisted living facilities. The drugs considered in this trial include a wide variety of potentially harmful drugs that have been shown in recent years to have adverse effects in this particular patient group. Intervention is pragmatic in nature, and its potential effects rely on those professionals who actually work with these older people. The nurses will be trained to identify the harmful drugs, whereas the final decision to stop these medications will be made by physicians consulting to these wards. Thus, if the intervention proves to be effective, it can be implemented easily.

The strength of this study is its pragmatic nature and easily implemented training. Thus, the findings should be applicable in real life. The population is frail and vulnerable and, according to our previous studies, uses a high number of these drugs. Thus, the floor effect is not easily reached in the primary endpoint. Besides the number of potentially harmful drugs, this study will also examine the effects of intervention on residents’ QOL. Contrary to many previous trials, this study will also collect data on participants’ hospitalizations. Inappropriate drugs according to Beers, anticholinergic drugs, as well as psychotropic drugs have been suggested to increase hospitalizations and complications[16, 19, 23, 25].

However, there are also potential limitations in this study. First, the population is old and frail with many comorbidities, and, thus, vulnerable to competing causes of complications and deaths. This may decrease the power of the study. The second challenge relates to a sufficient difference to be attained between the groups with our intervention. Contamination might be a problem, because the staff changes rapidly in these institutions and they may also move from intervention site to control site. The staff is also stressed, and it is unclear how they will accept our training. In addition, the staff will also learn about evidence-based treatments in this patient group (such as the beneficial effects of vitamin D, stroke prevention, dementia drugs, pain treatment), which may increase the number of medications, and, thus, may even have effects in the opposite direction from that intended in this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale intervention trial exploring the effects of educational intervention on reducing a wide variety of harmful drugs in institutionalized older people, as well as on their QOL, cognition and hospitalizations. This study will provide data whether modern learning methods have effects on decreasing the harmful consequences of these drugs.

Trial status

Ongoing, patient recruitment not completed at the time of submission.

Abbreviations

- ATC:

-

anatomical therapeutic chemical

- CDR:

-

clinical dementia rating scale

- HRQOL:

-

health-related quality of life

- LOCF:

-

last observation carried forward

- MDS:

-

Minimum Data Set

- MMSE:

-

Mini Mental State Examination

- MNA:

-

Mini Nutritional Assessment

- NSAID:

-

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PPI:

-

proton pump inhibitor

- Prn:

-

pro re nata

- PWB:

-

psychological well-being

- QOL:

-

quality of life

- RAI:

-

Resident Assessment Instrument

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SFINX:

-

Swedish Finnish INteraction X-referencing

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization.

References

Hosia-Randell HM, Muurinen SM, Pitkälä KH: Exposure to potentially inappropriate drugs and drug-drug interactions in elderly nursing home residents in Helsinki, Finland: a cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging. 2008, 25: 683-692. 10.2165/00002512-200825080-00005.

Olsson J, Bergman A, Carlsten A, Oké T, Bernsten C, Schmidt IK, Fastbom J: Quality of drug prescribing in elderly people in nursing homes and special care units for dementia: a cross-sectional computerized pharmacy register analysis. Clin Drug Investig. 2010, 30: 289-300. 10.2165/11534320-000000000-00000.

Onder G, Liperoti R, Fialova D, Topinkova E, Tosato M, Danese P, Gallo PF, Carpenter I, Finne-Soveri H, Gindin J, Bernabei R, Landi F: SHELTER project: polypharmacy in nursing home in Europe: results from the shelter study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012, 67A: 698-704. 10.1093/gerona/glr233.

Hosia-Randell H, Pitkälä K: Use of psychotropic drugs in elderly nursing home residents with and without dementia in Helsinki, Finland. Drugs Ageing. 2005, 22: 793-800. 10.2165/00002512-200522090-00008.

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, McCormick D, Jain S, Eckler M, Benser M, Bates DW: Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 2001, 161: 1629-1634. 10.1001/archinte.161.13.1629.

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Ruby CM, Weinberger M: Suboptimal prescribing in older inpatients and outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001, 49: 200-209. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49042.x.

Socialstyrelsen: Indikatorer för god läkemedelsterapi hos äldre. Artikelnr. 2010, 6: 29-[http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2010/2010-6-29] Accessed 29 February 2012,

Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC: Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1991, 151: 1825-832.

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH: Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163: 2716-2724. 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716.

McLeod PJ, Huang AR, Tamblyn RM, Gayton DC: Defining inappropriate practices in prescribing for elderly people: a national consensus panel. Can Med Assoc J. 1997, 156: 385-391.

Gallagher P, O'Mahony D: STOPP (Screening tool of older persons' potentially inappropriate prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers' criteria. Age Ageing. 2008, 37: 673-679. 10.1093/ageing/afn197.

Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, Hanlon JT: Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised?. Lancet. 2007, 370: 173-184. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5.

Raivio MM, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH: Use of inappropriate medications and their prognostic significance in hospital and nursing home patients with and without dementia in Finland. Drugs Aging. 2006, 23: 333-343. 10.2165/00002512-200623040-00006.

Lau DT, Kasper JD, Potter DE, Lyles A: Potentially inappropriate medication prescriptions among elderly nursing home residents: their scope and associated resident and facility characteristics. Health Serv Res. 2004, 39: 1257-1276. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00289.x.

Stafford AC, Alswayan MS, Tenni PC: Inappropriate prescribing in older residents of Australian care homes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011, 36: 33-44. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2009.01151.x.

Jano E, Aparasu RR: Healthcare outcomes associated with Beers' criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007, 41: 438-447. 10.1345/aph.1H473.

Borson S, Doane K: The impact of OBRA-87 on psychotropic drug prescribing in skilled nursing facilities. Psychiatr Serv. 1997, 48: 1289-1296.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P: Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005, 294: 1934-1943. 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934.

Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Fischer MA, Mogun H, Solomon DH, Brookhart MA: Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. 2005, 353: 2335-2341. 10.1056/NEJMoa052827.

Hartikainen S, Lönnroos E, Louhivuori K: Medication as a risk factor for falls: critical systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007, 62: 1172-1181. 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172.

Ancelin ML, Artero S, Portet F, Dupuy AM, Touchon J, Ritchie K: Non-degenerative mild cognitive impairment in elderly people and use of anticholinergic drugs: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2006, 332: 455-9. 10.1136/bmj.38740.439664.DE.

Uusvaara J, Pitkala KH, Tienari PJ, Kautiainen H, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE: Association between anticholinergic drugs and apolipoprotein e ε4 allele and poorer cognitive function in older cardiovascular patients: a cross-sectional study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57: 427-431. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02129.x.

Uusvaara J, Pitkala KH, Kautiainen H, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE: Association of anticholinergic drugs with hospitalization and mortality among older cardiovascular patients: a prospective study. Drugs Aging. 2011, 28: 131-138. 10.2165/11585060-000000000-00000.

Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE: The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 508-513. 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.106.

Bell S, Strandberg TE, Teramura-Gronblad M, Laurila JV, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH: Use of proton-pump inhibitors and mortality among institutionalized older people. Arch Intern Med. 2010, 170: 1604-1605. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.304.

Johnell K, Klarin I: The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf. 2007, 30: 911-918. 10.2165/00002018-200730100-00009.

SFINX - Lääkeaineiden yhteisvaikutukset (Swedish, Finnish, INteraction X-referencing). [http://www.terveysportti.fi/terveysportti/ia_yhteisvaikutus.koti] Accessed 29 February 2012,

Forsetlund L, Eike MC, Gjerberg E, Vist GE: Effect of interventions to reduce potentially inappropriate use of drugs in nursing homes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11: 16-10.1186/1471-2318-11-16.

Avorn J, Soumerai SB, Everitt DE, Ross-Degnan D, Beers MH, Sherman D, Salem-Schatz SR, Fields D: A randomized trial of a program to reduce the use of psychoactive drugs in nursing homes. N Engl J Med. 1992, 327: 168-173. 10.1056/NEJM199207163270306.

Meador KG, Taylor JA, Thapa PB, Fought RL, Ray WA: Predictors of antipsychotic withdrawal or dose reduction in a randomized controlled trial of provider education. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997, 45: 207-210.

Fossey J, Ballard C, Juszczak E, James I, Alder N, Jacoby R, Howard R: Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2006, 332: 756-761. 10.1136/bmj.38782.575868.7C.

Crotty M, Halbert J, Rowett D, Giles L, Birks R, Williams H, Whitehead C: An outreach geriatric medication advisory service in residential aged care: a randomised controlled trial of case conferencing. Age Ageing. 2004, 33: 612-617. 10.1093/ageing/afh213.

Patterson SM, Hughes CM, Crealey G, Cardwell C, Lapane KL: An evaluation of an adapted U.S. model of pharmaceutical care to improve psychoactive prescribing for nursing home residents in Northern Ireland (Fleetwood Northern Ireland study). J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010, 58: 44-53. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02617.x.

Roberts MS, Stokes JA, King MA, Lynne TA, Purdie DM, Glasziou PP, Wilson DA, McCarthy ST, Brooks GE, de Looze FJ, Del Mar CB: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of a clinical pharmacy intervention in 52 nursing homes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001, 51: 257-265.

Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, Giles LC, Phillips PA: Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2004, 2: 257-264. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2005.01.001.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975, 12: 189-198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL: A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982, 140: 566-572. 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566.

Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, Clark C: The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1989, 39: 1159-1165. 10.1212/WNL.39.9.1159.

Welsh K, Butters N, Hughes J, Mohs R, Heyman A: Detection of abnormal memory decline in mild cases of Alzheimer's disease using CERAD neuropsychological measures. Arch Neurol. 1991, 48: 278-281. 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530150046016.

Sunderland T: Hill JL, Mellow AM, Lawlor BA, Gundersheimer J, Newhouse PA. Grafman JH: Clock drawing in Alzheimer's disease. A novel measure of dementia severity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989, 37: 725-729.

Guigoz Y, Lauque S: Vellas BJ: Identifying the elderly at risk for malnutrition. The Mini Nutritional Assessment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002, 18: 737-757.

Routasalo PE, Tilvis RS, Kautiainen H, Pitkala KH: Effects of psychosocial group rehabilitation on social functioning, loneliness and well-being of lonely, older people: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2009, 65: 297-305. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04837.x.

Sintonen H: The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001, 33: 328-336. 10.3109/07853890109002086.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology: Anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system. ATC/DDD Index 2012. [http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/] Accessed 1 March 2012,

Morris JN, Fries BE, Bernabei R, Ikegami R, Carpenter I, Gilgen R, DuPasquier J, Frijters D, Henrard J, Hirdes JP, Belleville-Taylor P: RAI-home care (RAI-HC) assessment manual for version 2.0. 2000, Marblehead, MA: Opus Communications

Leikola S: Development and application of comprehensive medication review procedure to community-dwelling elderly. Dissertationes Biocentri Viikki Universitatis Helsingiensis. Helsinki University Printing House. 2012, 48: 65-Helsinki, Finland

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Sohlberg Foundation and a Helsinki University Central Hospital development grant. We also thank Helsinki City Social Services Department for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Dr Pitkälä reports professional cooperation, including lecturing fees from pharmaceutical and other health care companies (including Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, MSD Finland, Orion Pharma, Pfizer, Novartis, Nestle), and having participated in clinical trials funded by pharmaceutical companies. Dr Marja-Liisa Laakkonen has a few Orion Company shares but no other competing interests.

Dr Anna-Liisa Juola, Dr Helena Soini, Dr Hannu Kautiainen, Dr Mariko Teramura-Grönblad, Dr Harriet Finne-Soveri and Dr Mikko Björkman have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KHP, ALJ, HS, HK, HFS and MPB conceived and designed the study. KHP, ALJ, MLL, HK, HFS and MPB participated in the acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. KHP, ALJ, HS, MLL, HK, HFS, MTG and MPB drafted or critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. KHP, ALJ, HS, MLL, HK, HFS, MTG and MPB read and approved the final manuscript. KHP had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KHP is the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13063_2012_1163_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Table S1. Drugs considered as inappropriate, psychotropic or anticholinergic drugs in the present study. (DOC 44 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pitkala, K.H., Juola, AL., Soini, H. et al. Reducing inappropriate, anticholinergic and psychotropic drugs among older residents in assisted living facilities: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 13, 85 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-85

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-85