Abstract

Background

Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) constitute to be a high-risk population for the development of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), in which the incidence of CIN is estimated to be as high as 50%. We performed this trial to assess the efficacy of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) in the prevention of this complication.

Methods

In a prospective, double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trial, we studied 90 patients undergoing elective diagnostic coronary angiography with DM and CKD (serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL for men and ≥ 1.4 mg/dL for women). The patients were randomly assigned to receive either oral NAC (600 mg BID, starting 24 h before the procedure) or placebo, in adjunct to hydration. Serum creatinine was measured prior to and 48 h after coronary angiography. The primary end-point was the occurrence of CIN, defined as an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.5 mg/dL (44.2 μmol/L) or ≥ 25% above baseline at 48 h after exposure to contrast medium.

Results

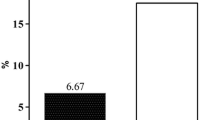

Complete data on the outcomes were available on 87 patients, 45 of whom had received NAC. There were no significant differences between the NAC and placebo groups in baseline characteristics, amount of hydration, or type and volume of contrast used, except in gender (male/female, 20/25 and 34/11, respectively; P = 0.005) and the use of statins (62.2% and 37.8%, respectively; P = 0.034). CIN occurred in 5 out of 45 (11.1%) patients in the NAC group and 6 out of 42 (14.3%) patients in the placebo group (P = 0.656).

Conclusion

There was no detectable benefit for the prophylactic administration of oral NAC over an aggressive hydration protocol in patients with DM and CKD.

Trial registration

NCT00808795

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is the third most common cause of hospital acquired acute kidney injury, accounting for 10% of all cases[1]. With the increasing use of contrast media in diagnostic and interventional procedures, it has become one of the major challenges encountered during routine cardiovascular practice. Generally, this form of acute kidney injury follows a benign course and only rarely necessitates use of dialysis [2–4]. Nevertheless, use of radiocontrast media has been associated with increased in-hospital morbidity, mortality, and costs of medical care, long admission, especially in patients needing dialysis [5–8]. Patients at the greatest risk for CIN can be defined as those that have preexisting impaired renal function and diabetes mellitus with the incidence estimated to be as high as 50% [9]. Therefore, these patients constitute to be an appropriate target population for efforts at prevention of this important complication. Preventive therapies primarily include limitation of contrast exposure, intravenous volume expansion with a saline solution, and use of low- or iso-osmolality contrast media [10]. However, since these measures provide incomplete protection for CIN, interest has emerged in a number of adjunction short-term pharmacotherapy methods. Among them, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has been of considerable interest after an initial report by Tepel et al. [11]. They showed a reduction in the incidence of CIN with NAC compared with hydration alone. Up to now, several clinical studies [9, 12–26] and meta-analyses [27–37] have been performed to assess the efficacy of NAC in the prevention of CIN, but the results are widely controversial even among the meta-analyses. In spite of heterogeneity in the available data on the efficacy of NAC, several studies have advised the use of NAC, especially in high-risk patients, because of its low cost, availability, and few side effects. It, however, seems that we need more evidence about the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of NAC in patients at high risk for the development of CIN to make rational clinical decisions for individual patients as well as policy decisions for the health of the general public.

The purpose of this study was to extend our understanding of the potentials of NAC in the prevention of CIN in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease.

Methods

Study patients

Between April 2006 and October 2006, ninety consecutive eligible patients scheduled for elective diagnostic coronary angiography at the cardiac catheterization laboratory of "Tehran Heart Center" (Tehran University of Medical Sciences) were enrolled in this study. We included patients older than 18 years old with a history of diabetes mellitus for at least one year and chronic kidney disease, defined as serum creatinine concentration ≥ 1.5 mg/dL for men and ≥ 1.4 mg/dL for women. Patients with acute coronary syndrome requiring primary or rescue coronary intervention within less than 12 h, cardiogenic shock, current peritoneal or hemodialysis, or a known allergy to NAC were excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Tehran Heart Center, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Study protocol

The study was a prospective, double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized clinical trial. The patients were randomly assigned on a 1:1 fashion via the balanced block randomization method using computer generated random numbers to receive NAC or placebo by randomly drawing sealed envelopes containing either the active drug or matching placebo. NAC and placebo were prepared by Darmanyab Co. (agency of Zambon Group S.p.A, Milan, Italy) matched in appearance, packing, and way of use. NAC was orally administered at the dose of 600 mg twice a day, starting 24 h before the procedure (two doses before and two doses after the procedure). The patients were hydrated orally and intravenously. All the patients were encouraged to drink fluids like water and fruit juice for at least 8 glasses over 12 h before the procedure and memorize the number of glasses. The oral pre-procedural hydration was estimated by multiplying the number of glasses drunk by 200 mL (estimated volume of a glass). In addition, the patients were hydrated intravenously by 1 L of 0.9 normal saline, which was commenced in the catheterization laboratory. Serum creatinine and urea nitrogen concentrations were measured prior to coronary angiography and 48 h after the procedure. Serum creatinine concentration prior to coronary angiography was referred to as the baseline level. Creatinine clearance (CrCl) was estimated with the Cockcroft-Gault formula, where CrCl = ([140-age]*weight(kg)/serum creatinine(mg/dL)*72), with adjustment for female sex (CrClfemale = CrCl*0.85)[38]. Coronary angiographies were performed with the low osmolar nonionic contrast medium Iohexol (Omnipaque; Amersham Health, Co. Cork, Ireland) or the iso-osmolar nonionic contrast medium Iodixanol (Visipaque;GE Healthcare, Co. Cork, Ireland) and/or the high osmolar ionic medium Diatrizoate meglumine/sodium (Urografin; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany).

End-points

The primary end-point of the study was the occurrence of CIN, defined as an increase in serum creatinine concentration ≥ 0.5 mg/dL(44.2 μmol/L) or ≥ 25% above the baseline at 48 h after exposure to the contrast medium[5, 11]. The secondary end-points were: (1) the change in serum creatinine 48 h after exposure to the contrast agent; (2) the change in serum urea nitrogen 48 h after the procedure; and (3) the change in CrCl 48 h after coronary angiography.

Statistical analysis

According on the study of Tepel et al[11], a sample size of 42 patients in each group would be sufficient to detect a difference of 19% between the groups in the rate of CIN at 48 h after exposure to the contrast medium, with 80% power and a 5% significance level. This 19% difference represents the difference between a 21% CIN rate in the placebo group and a 2% rate in the treatment group. This number has been increased to 45 per group to allow for a predicted drop-out from treatment of around 5%.

Data distribution was checked by histogram and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

The continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD and were compared via the Student t-test. The categorical data were expressed as number and percentage and were compared via the Chi-square test or Fischer exact test. Two tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 13.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Patients

Of the 90 patients enrolled in the study, 3 patients in placebo group were lost to follow-up because of immediate hospital discharge after coronary angiography and failure to have subsequent blood sampling performed. Thus, only 42 patients were evaluable for the assessment of the outcomes in the placebo group. We present the baseline clinical, pharmacological, and laboratory characteristics of the study patients in Table 1.

There were no significant differences between the treatment groups with regard to CHD risk factors, baseline serum creatinine, and urea nitrogen concentration or CrCl except for the gender, which was significantly different between the two groups of patients (P = 0.005). Also, with respect to concomitant medications, there were no significant differences between the NAC group and placebo group except in the use of statins (62.2% versus 37.8% respectively, P = 0.034). Cardiac catheterization data, consisting of type and dose of the contrast agents, are shown in Table 2. Since 22 patients received a combination of Diatrizoate meglumine/sodium with Iohexol or Iodixanol, we also calculated the total dose of contrast in each group. There were no significant differences between the two groups in regard to the type and dose of the radiocontrast agents administered for coronary angiography (P for all > 0.05).

Primary end-point

CIN, defined as an increase in serum creatinine concentration of ≥ 0.5 mg/dL or ≥ 25% above the baseline, was not significantly different between the NAC and placebo groups (5/45 [11.1%] vs. 6/42 [14.3%], respectively; relative risk: 0.78 [95% CI: 0.26–2.36]; P = 0.656).

Secondary end-point

No difference was observed between the groups regarding the secondary end-points. The changes in serum creatinine, serum urea nitrogen, and CrCl 48 h after coronary angiography were similar between the groups. The data are presented in Table 3.

Discussion

The potential of NAC to reduce the risk of CIN has been a topic of intense and recent interest, manifested by the number of prospective clinical trials on this topic [9, 12–26]. This is likely, in part, due to the absence of effective adjunctive pharmacotherapy methods for this important complication. However, it seems likely that the potential for benefit from NAC, low cost, and the absence of considerable data indicating potential harm also have contributed to make NAC advisable, not least in high-risk patients, before a definitive demonstration of meaningful clinical benefit on the incidence of CIN and its morbidity and mortality.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of NAC exclusively in high-risk patients for the development of CIN. The main finding of the current study was that the prophylactic oral administration of NAC did not provide any benefit as compared with a placebo to reduce the incidence of CIN in patients with chronic kidney disease and diabetes mellitus, who are a high-risk population for the development of CIN. Our findings are consistent with those in studies reporting that NAC provides no benefit over hydration for the prevention of CIN [12, 13, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23]. In addition, our study supports and expands the studies by Coyle et al[26], Durham et al. [17], and Gomes et al. [9, 24], who evaluated the efficacy of NAC in the prevention of CIN in diabetic patients. They concluded that NAC provided no benefit over an aggressive hydration protocol in this population and also suggested that this intervention could even be harmful. But, on the other hand, there are several clinical studies reporting findings that do not chime with ours [9, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25]. Previously, a post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of 75 diabetic patients [21] indicated that NAC might effectively prevent CIN in patients with diabetes mellitus but our study did not confirm this finding.

What are we to make of such conflicting results? Fishbane et al. [39]compared positive and negative studies and noted that the studies showing no benefit for NAC had a much lower incidence of CIN in the placebo group than did those studies showing NAC to be beneficial (11.0% compared to 24.8%). These results suggest that perhaps NAC is only beneficial for those at a high risk of CIN. Be that as it may, in this study we were unable to show a benefit resulting from the prophylactic administration of oral NAC in a high-risk group of patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal insufficiency (mean baseline creatinine 1.74 mg/dL).

The incidence of CIN is currently estimated to be as high as 40–50% amongst patients with diabetes mellitus and preexisting renal disease [6, 9, 16]. In this study, the overall incidence of CIN was 12.6%, which is significantly lower than that in previous reports. The low incidence of CIN in our study may have several reasons: (1) our patients were hydrated orally by a mean volume of 2267 ± 645 mL of fluids over the 12-h period before the procedure followed by 1 L of IV 0.9 normal saline beginning in the catheterization laboratory. In comparison, the other studies reporting a higher incidence of CIN, have typically used lower amounts of hydration [9, 40, 41], which may be insufficient for maximal protection from contrast nephrotoxicity. (2) The mean dose of contrast agents used in our study was lower than that of other studies. Over 95% of the patients in our study received Iohexol at least in part and the mean total dose of Iohexol used in our study was about 100 mL, while it has typically been used by amounts of 140 mL to 280 mL in the previous studies [15, 25, 42].

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. The current study protocol excluded patients with acute coronary syndrome, requiring primary or rescue coronary intervention within the first 12 h and cardiogenic shock, and therefore the effect of NAC was not explored in these patient subsets. The relatively small sample size of this study calls for caution interpreting the results. This sample size was predetermined from a power calculation based on the findings of Tepel et al[11]. They found a 19% difference in the rate of CIN between NAC and placebo groups, which was more extreme than what others have cited in favor of NAC. Another potential limitation of this study is that, although there were no significant differences between the NAC group and placebo group with regard to the type of the contrast agents used, the multiplicity of the type of the contrast agents was a potential limitation of this study.

Conclusion

Our major finding was that NAC had no advantage over an aggressive hydration protocol in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal insufficiency undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography. On the basis of these findings, we believe that the use of NAC to prevent CIN in this population should not be encouraged. Our findings support that the recommended measures for preventing CIN continue to be appropriate hydration, even greater than the standard regimen for hydration, and the use of a small volume of contrast in patients with a high risk of CIN undergoing coronary angiography.

Abbreviations

- CIN:

-

contrast-induced nephropathy

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- NAC :

-

N-acetylcysteine.

References

Hou SH, Bushinsky DA, Wish JB, Cohen JJ, Harrington JT: Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency: a prospective study. Am J Med. 1983, 74: 243-248. 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90618-6.

Murphy SW, Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS: Contrast nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000, 11: 177-182.

Parfrey PS, Griffiths SM, Barrett BJ, Paul MD, Genge M, Withers J, Farid N, McManamon PJ: Contrast material-induced renal failure in patients with diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, or both. A prospective controlled study. N Engl J Med. 1989, 320: 143-149.

Rich MW, Crecelius CA: Incidence, risk factors, and clinical course of acute renal insufficiency after cardiac catheterization in patients 70 years of age or older. A prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 1990, 150: 1237-1242. 10.1001/archinte.150.6.1237.

McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O'Neill WW: Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality. Am J Med. 1997, 103: 368-375. 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00150-2.

Gruberg L, Mintz GS, Mehran R, Gangas G, Lansky AJ, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Leon MB: The prognostic implications of further renal function deterioration within 48 h of interventional coronary procedures in patients with pre-existent chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000, 36: 1542-1548. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00917-7.

Levy EM, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI: The effect of acute renal failure on mortality. A cohort analysis. JAMA. 1996, 275: 1489-1494. 10.1001/jama.275.19.1489. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/275/19/1489

Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, Singh M, Bell MR, Barsness GW, Mathew V: Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002, 105: 2259-2264. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000016043.87291.33.

Chen SL, Zhang J, Yei F, Zhu Z, Liu Z, Lin S, Chu J, Yan J, Zhang R, Kwan TW: Clinical outcomes of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective, multicenter, randomized study to analyze the effect of hydration and acetylcysteine. Int J Cardiol. 2008, 126: 407-413. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.05.004.

Solomon R, Deray G: How to prevent contrast-induced nephropathy and manage risk patients: practical recommendations. Kidney Int Suppl. 2006, S51-53. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000375.

Tepel M, Giet van der M, Schwarzfeld C, Laufer U, Liermann D, Zidek W: Prevention of radiographic-contrast-agent-induced reductions in renal function by acetylcysteine. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 180-184. 10.1056/NEJM200007203430304.

Efrati S, Dishy V, Averbukh M, Blatt A, Krakover R, Weisgarten J, Morrow JD, Stein MC, Golik A: The effect of N-acetylcysteine on renal function, nitric oxide, and oxidative stress after angiography. Kidney Int. 2003, 64: 2182-2187. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00322.x.

Briguori C, Manganelli F, Scarpato P, Elia PP, Golia B, Riviezzo G, Lepore S, Librera M, Villari B, Colombo A, Ricciardelli B: Acetylcysteine and contrast agent-associated nephrotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40: 298-303. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01958-7.

Recio-Mayoral A, Chaparro M, Prado B, Cozar R, Mendez I, Banerjee D, Kaski JC, Cubero J, Cruz JM: The reno-protective effect of hydration with sodium bicarbonate plus N-acetylcysteine in patients undergoing emergency percutaneous coronary intervention: the RENO Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 49: 1283-1288. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.034.

Carbonell N, Blasco M, Sanjuan R, Perez-Sancho E, Sanchis J, Insa L, Bodi V, Nunez J, Garcia-Ramon R, Miguel A: Intravenous N-acetylcysteine for preventing contrast-induced nephropathy: a randomised trial. Int J Cardiol. 2007, 115: 57-62. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.04.023.

Baker CS, Wragg A, Kumar S, De Palma R, Baker LR, Knight CJ: A rapid protocol for the prevention of contrast-induced renal dysfunction: the RAPPID study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 41: 2114-2118. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00487-X.

Durham JD, Caputo C, Dokko J, Zaharakis T, Pahlavan M, Keltz J, Dutka P, Marzo K, Maesaka JK, Fishbane S: A randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine to prevent contrast nephropathy in cardiac angiography. Kidney Int. 2002, 62: 2202-2207. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00673.x.

Diaz-Sandoval LJ, Kosowsky BD, Losordo DW: Acetylcysteine to prevent angiography-related renal tissue injury (the APART trial). Am J Cardiol. 2002, 89: 356-358. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02243-3.

Shyu KG, Cheng JJ, Kuan P: Acetylcysteine protects against acute renal damage in patients with abnormal renal function undergoing a coronary procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40: 1383-1388. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02308-2.

Goldenberg I, Shechter M, Matetzky S, Jonas M, Adam M, Pres H, Elian D, Agranat O, Schwammenthal E, Guetta V: Oral acetylcysteine as an adjunct to saline hydration for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy following coronary angiography. A randomized controlled trial and review of the current literature. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25: 212-218. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.011.

Kay J, Chow WH, Chan TM, Lo SK, Kwok OH, Yip A, Fan K, Lee CH, Lam WF: Acetylcysteine for prevention of acute deterioration of renal function following elective coronary angiography and intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003, 289: 553-558. 10.1001/jama.289.5.553.

Seyon RA, Jensen LA, Ferguson IA, Williams RG: Efficacy of N-acetylcysteine and hydration versus placebo and hydration in decreasing contrast-induced renal dysfunction in patients undergoing coronary angiography with or without concomitant percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Lung. 2007, 36: 195-204. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.08.004.

Sandhu C, Belli AM, Oliveira DB: The role of N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of contrast-induced nephrotoxicity. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006, 29: 344-347. 10.1007/s00270-005-0127-8.

Gomes VO, Poli de Figueredo CE, Caramori P, Lasevitch R, Bodanese LC, Araujo A, Roedel AP, Caramori AP, Brito FS, Bezerra HG: N-acetylcysteine does not prevent contrast induced nephropathy after cardiac catheterisation with an ionic low osmolality contrast medium: a multicentre clinical trial. Heart. 2005, 91: 774-778. 10.1136/hrt.2004.039636.

Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Marana I, Lauri G, Campodonico J, Grazi M, De Metrio M, Galli S, Fabbiocchi F, Montorsi P: N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy in primary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354: 2773-2782. 10.1056/NEJMoa054209.

Coyle LC, Rodriguez A, Jeschke RE, Simon-Lee A, Abbott KC, Taylor AJ: Acetylcysteine In Diabetes (AID): a randomized study of acetylcysteine for the prevention of contrast nephropathy in diabetics. Am Heart J. 2006, 151: 1032.e9-1032.e12. 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.002.

Nallamothu BK, Shojania KG, Saint S, Hofer TP, Humes HD, Moscucci M, Bates ER: Is acetylcysteine effective in preventing contrast-related nephropathy? A meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2004, 117: 938-947. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.046.

Isenbarger DW, Kent SM, O'Malley PG: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on the usefulness of acetylcysteine for prevention of contrast nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2003, 92: 1454-1458. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.059.

Birck R, Krzossok S, Markowetz F, Schnulle P, Woude van der FJ, Braun C: Acetylcysteine for prevention of contrast nephropathy: meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003, 362: 598-603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14189-X.

Bagshaw SM, Ghali WA: Acetylcysteine for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy after intravascular angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2004, 2: 38-10.1186/1741-7015-2-38.

Kshirsagar AV, Poole C, Mottl A, Shoham D, Franceschini N, Tudor G, Agrawal M, Denu-Ciocca C, Magnus Ohman E, Finn WF: N-acetylcysteine for the prevention of radiocontrast induced nephropathy: a meta-analysis of prospective controlled trials. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004, 15: 761-769. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000116241.47678.49.

Pannu N, Manns B, Lee H, Tonelli M: Systematic review of the impact of N-acetylcysteine on contrast nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2004, 65: 1366-1374. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00516.x.

Liu R, Nair D, Ix J, Moore DH, Bent S: N-acetylcysteine for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2005, 20: 193-200. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30323.x.

Duong MH, MacKenzie TA, Malenka DJ: N-acetylcysteine prophylaxis significantly reduces the risk of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy: comprehensive meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005, 64: 471-479. 10.1002/ccd.20342.

Zagler A, Azadpour M, Mercado C, Hennekens CH: N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2006, 151: 140-145. 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.055.

Gonzales DA, Norsworthy KJ, Kern SJ, Banks S, Sieving PC, Star RA, Natanson C, Danner RL: A meta-analysis of N-acetylcysteine in contrast-induced nephrotoxicity: unsupervised clustering to resolve heterogeneity. BMC Med. 2007, 5: 32-10.1186/1741-7015-5-32.

Kelly AM, Dwamena B, Cronin P, Bernstein SJ, Carlos RC: Meta-analysis: effectiveness of drugs for preventing contrast-induced nephropathy. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 284-294. http://www.annals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18283206

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH: Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976, 16: 31-41. 10.1159/000180580.

Fishbane S, Durham JH, Marzo K, Rudnick M: N-acetylcysteine in the prevention of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004, 15: 251-260. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000107562.68920.92.

Aspelin P, Aubry P, Fransson SG, Strasser R, Willenbrock R, Berg KJ: Nephrotoxic effects in high-risk patients undergoing angiography. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348: 491-499. 10.1056/NEJMoa021833.

Tumlin JA, Wang A, Murray PT, Mathur VS: Fenoldopam mesylate blocks reductions in renal plasma flow after radiocontrast dye infusion: a pilot trial in the prevention of contrast nephropathy. Am Heart J. 2002, 143: 894-903. 10.1067/mhj.2002.122118.

Rashid ST, Salman M, Myint F, Baker DM, Agarwal S, Sweny P, Hamilton G: Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in vascular patients undergoing angiography: a randomized controlled trial of intravenous N-acetylcysteine. J Vasc Surg. 2004, 40: 1136-1141. 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.026.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MA was responsible for trial designing, supervision of the trial implementation, and writing the article. MS was responsible for trial designing and angiographic studies. AA was responsible for study design, trial implementation, visiting patients, patients' follow-up, and writing the article. FM was responsible for epidemiologic consultation, statistical analysis, and writing the article. FE was responsible for epidemiologic consultation and statistical analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Amini, M., Salarifar, M., Amirbaigloo, A. et al. N-acetylcysteine does not prevent contrast-induced nephropathy after cardiac catheterization in patients with diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease: a randomized clinical trial. Trials 10, 45 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-10-45

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-10-45