Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common chronic neurodevelopmental disorder with a high heritability. Much evidence of hemisphere asymmetry has been found for ADHD probands from behavioral level, electrophysiological level and brain morphology. One previous research has reported possible association between BAIAP2, which is asymmetrically expressed in the two cerebral hemispheres, with ADHD in European population. The present study aimed to investigate the association between BAIAP2 and ADHD in Chinese Han subjects.

Methods

A total of 1,397 ADHD trios comprised of one ADHD proband and their parents were included for family-based association tests. Independent 569 ADHD cases and 957 normal controls were included for case-control studies. Diagnosis was performed according to the DSM-IV criteria. Nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of BAIAP2 were chosen and performed genotyping for both family-based and case-control association studies.

Results

Transmission disequilibrium tests (TDTs) for family-based association studies showed significant association between the CA haplotype comprised by rs3934492 and rs9901648 with predominantly inattentive type (ADHD-I). For case-control study, chi-square tests provided evidence for the contribution of SNP rs4969239, rs3934492 and rs4969385 to ADHD and its two clinical subtypes, ADHD-I and ADHD-C. However, only the associations for ADHD and ADHD-I retained significant after corrections for multiplicity or logistic regression analyses adjusting the potential confounding effect of gender and age.

Conclusions

These above results indicated the possible involvement of BAIAP2 in the etiology of ADHD, especially ADHD-I.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder. The high heritability of approximately 0.76 [1] has suggested the important role of genetic factors in its etiology.

The typical development of human cerebral asymmetry has profound effect on the normal lateralization of cognitive and motor functions, such as language and handedness. Several studies have suggested the possible link of the disturbance of cerebral asymmetry with the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders [2], such as schizophrenia [3], autism [4] and ADHD [5].

The non-right-handedness, especially mixed-handedness, might be a risk indicator for the symptom severity of inattention in ADHD [6]. One of our previous behavioral studies indicated that ADHD children showed an atypical pattern of right hemisphere in conflict control task compared to controls [7]. Another study demonstrated that the direction of spatially asymmetrical interference effects in ADHD was opposite to controls, indicating disruption within right hemisphere attentional networks [8]. The structural imaging findings in ADHD has demonstrated volumetric reductions in total and right cerebral, right caudate, cerebellar and corpus callosum [9]. ADHD adults had thinner cortex in the cortical networks, especially in the right hemisphere involving inferior parietal lobule, dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices [10]. In addition, some evidence has showed that the critical feature of ADHD is the delayed maturation not only of prefrontal cortical thickness but also of cortical surface area, especially the right hemispheric lobes [11, 12]. The degree of rightward volumetric asymmetry in caudate nucleus might predict the severity of inattentive symptoms of ADHD [13]. An fMRI study of ADHD children showed under-activation of the right caudate nucleus and inferior parieta cortex [14].

The gene BAIAP2, which is located on 17q25 and encodes brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor 1-associated protein 2 (BAIAP2), has been suggested to be involved in cerebral asymmetry [15]. Recently, a genetic study of adulthood ADHD in two independent European populations suggested an association of BAIAP2 with ADHD, supplying genetic evidence of abnormal left-right brain asymmetries with this disorder [16]. In addition, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) has indicated nominal association between BAIAP2 and its isoform BAIAP2L1 with ADHD [17]. Moreover, methamphetamine, one of psychostimulants being considered as first-line pharmacological treatments for ADHD patients, has enhanced the expression of BAIAP2 in rat cerebral cortices [18]. BAIAP2 has also been found to confer risk for autism spectrum disorders (ASD), which shared some genetic risk factors with ADHD [19].

For the potentially important role of cerebral asymmetry in the pathophysiology of ADHD, BAIAP2 has been suggested to be one of novel candidate genes for ADHD, but need more work for replication [20]. Our present study is to investigate the relationship between BAIAP2 and ADHD in Chinese Han subjects.

Methods

Subjects

All ADHD cases were recruited from child psychiatric clinics of Peking University Institute of Mental Health. Diagnosis was performed according to the DSM-IV criteria by experienced child psychiatrists, using the Clinical Diagnostic Interview Scale (CDIS) [21], which was translated into Chinese by our groups before [22, 23]. The CDIS assesses the three DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD, including ADHD inattentive type (ADHD-I), ADHD hyperactive-impulsive type (ADHD-HI) and ADHD combined type (ADHD-C). It was also used to evaluate comorbidities, including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), tic disorder (TD), learning disorder (LD), etc. The diagnosis of LD is just based on a brief parents’ report of the general academic achievement, but not including detailed assessment for reading, writing or arithmetic abilities. So dyslexia, dysgraphia or dyscalculia was not defined in our current study. All cases were of Chinese Han descent, with age between 6 and 16 years, and full-scale estimated IQ > 70. Any major neurological disorders, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, pervasive development disorder, epilepsy, mental retardation or other brain disorders were excluded. Finally, a total of 1,966 ADHD probands were included. Among these cases, 1,397 ADHD probands, along with their parents, constituted trios for family-based association analyses. The other independent 569 ADHD cases were included for case-control study.

The control sample consisted of 957 subjects from local elementary schools, healthy blood donors from the blood center of the First Hospital of Peking University, and healthy volunteers at our institute. ADHD, other major psychiatric disorders, family history of psychosis, severe physical diseases and substance abuse were excluded (more details have been described in our previously published article [24]). Demographic and clinical characteristics of both ADHD cases and control sample are shown in Table 1.

All subjects were treated according to the Declaration of Helsinki and this work was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Health Science Center. Written informed consent was obtained from each subjects or parents of children.

DNA isolation

Peripheral blood was collected for all subjects included in this study. Then genomic DNA was extracted following the standard protocols using E.Z.N.A.™ Blood DNA Kits (Omega Bio-tek Inc., Doraville, GA).

SNP selection and genotyping

For selection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), Haploview version 4.2 was used to pick up tag SNPs based on the CHB database from Hapmap (http://www.hapmap.org). Threshold limit was set of r2 > 0.80 for all SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.25. Thirteen tag SNPs were chosen with these criteria. However, only eight tag SNPs were included for genotyping and further association analyses. The other five SNPs were not selected for the location at the same haplotype block or strong to moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD) with those selected SNPs (Table 2). We also included an additional SNP rs4969385 located on intron 6, which was found to be potentially associated with adult ADHD in Spanish population [16].

Genotyping for all SNPs were carried out on an ABI 7900-HT instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA), using Taqman allelic genotyping assays [25] and following the standard protocol as described by our previous report [26]. The SDS version 2.3 software was used for genotype identification. For quality control, firstly, two to four non-template controls (NTC) were set on each 384-well plate with no genotype called. Secondly, 3% samples were selected randomly and genotyped for the same SNP by different experimenters, indicating the concordance rate of 100%. Call rates for all SNPs were ranging from 98.8% to 99.5%.

Statistical analyses

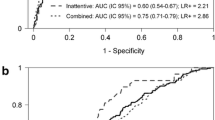

Calculation of MAF and analysis of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) were performed using Haploview 4.2 software for cases and controls separately, showing no departure from HWE for any SNP (P-value from 0.178 to 0.921). The MAFs for all SNPs were from 0.162 to 0.499. Haploview software was also used to estimate the linkage disequilibrium (LD) of all SNPs and generate haplotype blocks which will be used for multi-marker haplotype-based association tests [27]. As shown by Figure 1, there were three haplotype blocks generated including Block 1 comprised of SNP 1–4, Block 2 comprised of SNP 5–6 and Block 3 comprised of SNP 8–9. However, the SNP7 rs4076037 was not included into any block and subsequently not included for multi-marker analyses. For Block 1, only three of seven generated haplotypes (ACAA, GAGG and ACGG) were used for haplotype analyses, which captured 85.3% of the genetic variance in the investigated four SNPs, while the other four haplotypes with frequencies < 0.1 were not included.

For family-based association study, TDT tests were conducted using Haploview to investigate whether there was biased-transmission of alleles or haplotypes in ADHD trios. For case-control study, chi-square tests were conducted using Haploview for both single-marker and multi-marker haplotype-based analyses, to compare the frequencies of alleles and haplotypes between ADHD cases and controls. In addition, comparison of the genotype frequencies was also performed for case-control statistics using SPSS software. Once there was nominally significant association appeared either for alleles or genotypes under additive model (nominal P < 0.05), further analyses for genotypes based on dominant and recessive models were conducted [16]. As indicated in Table 1, the comparisons of distribution of gender and age between two groups showed statistical significance. Then, we further developed logistic regression analyses to control the potential confounding effect of gender and age.

For multiple testing corrections of single-marker analyses, Bonferroni corrections were conducted. We firstly used SNPSpD software [28] to consider the inter-correlation of SNPs for multiple testing of SNPs in LD with each other. For our current study, the effective number of independent marker loci yielded by SNPSpD was 7. Then, for TDT tests, taking into account three clinical subtypes and the effective number of SNPs (n = 7), the experiment-wide significance threshold required to keep type I error rate at 5% was set at P < 0.0024. For case-control study, considering the effective number of SNPs (n = 7), three clinical subtype, and the comparison of genotype and allele frequencies, the adjusted significance was set at P < 0.0012. For multi-marker association tests, haplotype analysis was only conducted when nominal association existed in the single-marker analyses and significance was corrected by 5,000 permutations using Haploview software.

The minimum statistically genetic power for TDT tests and case-control studies was calculated using the Genetic Power Calculator software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/gpc/), taking the lowest MAF of 0.162 and assuming the prevalence of 0.05, significance level of 0.05 and odd ratio (OR) of 1.5. Under above settings, our sample showed the minimum statistically genetic power of 80.9% for TDT statistics with about 500 efficient trios, and 74.4% for 569 cases vs. 957 controls under additive model.

Results

Family-based association tests

Single-marker analyses

In the general ADHD trios, we did not find any biased transmission of any allele for any SNP (all P > 0.05, Table 3). Further analyses were conducted for three subtypes separately. For ADHD-I trios, TDT tests showed that the C allele of SNP rs3934492 was over-transmitted with nominal P-value of 0.030 (Table 3). No biased-transmission was found either in ADHD-HI or in ADHD-C trios (all P values > 0.05, Table 3).

Multi-marker haplotype-based association tests

Haplotype analyses were only conducted for ADHD-I trios. The CA haplotype of Block 2 coded by rs3934492 and rs9901648 was over-transmitted (χ2=11.18, nominal P=8.0e-4, empirical P=0.005) and the GA haplotype was potentially under-transmitted (χ2=4.66, nominal P = 0.031, empirical P=0.207) (Table 4).

Case-control studies

Single-marker analyses

For allelic analyses, nominal association was displayed with ADHD for SNP rs4969385 (χ2=5.59, P = 0.018, OR = 1.27 [1.04-1.55]) (Table 5). What’s more, the potential confounding factors of subtypes were considered by analyses in ADHD-I and ADHD-C separately, while ADHD-HI was not analyzed due to its small sample size. Two SNPs showed association with ADHD-I: rs4969239 (χ2=6.58, P = 0.010, OR = 1.29 [1.06-1.58]) and rs3934492 (χ2=4.28, P = 0.039, OR = 1.22 [1.01-1.48]). One SNP rs4969385 showed association with ADHD-C (χ2=4.14, P = 0.042, OR = 1.31 [1.01-1.71]) (Table 5).

Genotypic analyses also support association between above SNPs with ADHD, ADHD-I and ADHD-C (Table 5). However, only the association of rs4969385 with ADHD (P = 0.001, OR = 2.96 [1.51-5.81]) and ADHD-I (P = 0.001, OR = 3.48 [1.64-7.39]) retained significant after corrections for multiplicity, but not for ADHD-C (P = 0.040, OR = 2.64 [1.13-6.17]) (Table 5). Logistic regression analyses also showed retained association of BAIAP2 with ADHD (P < 0.05) and ADHD-I (P < 0.05) after adjusting the potential effect of gender and age, but not for ADHD-C (P = 0.086) (Table 6).

Multi-marker haplotype-based association tests

Based on the association from single-marker analyses, we performed haplotype analyses for ADHD, ADHD-I and ADHD-C. As indicated in Table 7, the CT haplotype of Block3 showed nominal association with ADHD in general (χ2=5.44, nominal P = 0.019, empirical P = 0.097). For ADHD-I, the GA haplotype of Block2 showed lower frequency (χ2=3.98, nominal P = 0.046, empirical P = 0.217) in cases than controls, while the CA haplotype showed higher frequency (χ2=5.20, nominal P = 0.023, empirical P = 0.110). For ADHD-C, the CT heplotype of Block3 showed hither frequency in cases (χ2=3.96, nominal P = 0.047, empirical P = 0.215). However, none of above association remained significant after permutations.

Discussion

Our results showed that BAIAP2 was associated with childhood ADHD of Chinese Han descent, especially for the predominantly inattentive type (ADHD-I). Analyses for case-control studies indicated different alleles and genotypes distribution between ADHD and controls, and the association was only retained for ADHD and ADHD-I after multiple corrections or adjusting the confounding effect of gender and age, but not for ADHD-C. From TDT tests for trios, the significant association was only indicated for ADHD-I from haplotype analyses.

In some extent, our current findings are consistant with previous reports. Ribasés et al. [16] have analyzed six functional candidate genes showing differential expression between hemispheres in ADHD and normal controls, but only found an association between BAIAP2 with ADHD. However, in their study, the association of BAIAP2 with ADHD was only observed in adults, which has also been replicated in an independent population, but not children. The possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that the genetic load for ADHD children may be lower than ADHD adults, while the sample size in the study by Ribasés et al. [16] may be not enough to detect the relatively weak association in ADHD children. Further investigation in ADHD adults of Chinese Han descent especially by follow-up studies may promote our understanding of the explicit effect of BAIAP2 on ADHD.

In our present study, the SNP rs4969385 was the only associated one with ADHD and ADHD-I after corrections for multiple testing. This SNP has also been reported in adult samples by Ribasés et al. [16]. This replication suggested further exploration of this SNP and its related functional variants in the predisposition to ADHD. However, we note that the direction of the effect in our current study was opposite to the one observed by Ribasés et al. [16]. In our study, the minor ‘T’ allele showed risk for ADHD, while the major ‘C’ allele did in Ribasés’s report. Previous studies has also reported similar phenomenon between different ethnicities [29, 30]. In addition, another SNP rs8079626, showing none association in our current study, has been reported to be of nominal association with adult ADHD in German sample by Ribasés et al. [16]. In their study, the ‘A’ allele showed higher frequencies in German adult ADHD sample than controls. In our study, for the ‘G’ allele, the transmission was more than non-transmission from TDT tests and its frequency was higher in ADHD probands versus controls, although not achieving statistically significant difference. When checking the LD between rs8079626 with the best two SNPs of our current analyses, we found its low LDs with rs3934492 (D’ = 0.231, r2 = 0.04) and rs4969385 (D’ = 0.072, r2 = 0.002). So we can conclude that the SNP rs8079626 was not associated with ADHD in Chinese Han subjects. This discrepancy may be greatly due to the ethnic difference, that its allele distribution in our current analyses of Chinese Han subjects (62.8% of G, 37.2% of A) was adverse to that of German samples (31.0% of G, 69.0% of A) from the study by Ribasés et al. [16]. This adverse distribution is according with the Hapmap database (62.2% of G for CHB, 28.3% of G for CEU). Taken together, it is very important to consider potential pathogenic genetic variants in different ethnic populations for ADHD etiological studies.

Another interesting finding is the specific association of BAIAP2 with ADHD-I subtype. Three subtypes of ADHD were defined in DSM-IV including predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and the combined subtypes [31]. A growing body of literature has addressed that inattentive and combined subtypes may be distinct disorders [32, 33]. Attention-deficit disorder (ADD; inattentive, without hyperactivity) was different from ADHD on genetic basis, comorbidity, related brain region, etc. (for a review, see [33]). These findings have some effect on the revision of ADHD subtypes in DSM-V [34]. Our previous studies on molecular genetics have revealed the potential subtype-specific genes associated with ADHD in the Chinese Han population. COMT, 5-HT1B, MAOA, CHRNA4, SYP and DDC exhibited associations primarily with ADHD-I, whereas HTR2C, 5-HT1D, ADRA2C, DRD3 and NET1 were associated mainly with ADHD-C [24, 35–38]. The family-based study of NET1 and ADHD strongly suggested that the haplotype blocks within different regions of NET1 show divergent association based on sex and subtype [39]. Taken the current finding together with previous reports, considering subtypes in ADHD genetic studies is very important to reduce the heterogeneity and may help us to explore the hidden existed genes associated with ADHD.

Our findings need to be considered in light of some limitations. Firstly, twenty-seven genes have been identified involving in the left-right asymmetric cortical development in humans [15]. We only included BAIAP2 in this study and whether other genes played the role for the pathogenesis of ADHD remained unclear. Secondly, we have set MAF > 0.25 for tag SNPs selection and included an additional reported SNP rs4969385 with MAF of 0.162. We could not preclude the rare genetic contribution of uncommon SNPs (MAF <0.162) to the occurrence of ADHD. Thirdly, we have not screened those parents for ADHD diagnosis that we could not explain the genetic mechanisms of BAIAP2 in the etiology of ADHD clearly. Fourthly, ADHD was associated with high rates of comorbidity including dyslexia (reading disorder). In the existing literature, evidence has support the common risk neurobiological phenotype of atypical cerebral asymmetry (ACA) and shared ACA genes for ADHD and dyslexia [40]. The diagnosis instrument as described above in the present study lacked the ability to differ ADHD from dyslexia. Lastly, we did not collect data on the handedness, which is also strongly correlated with cerebral asymmetry. Then, we could not preclude the confounding effect of the diagnosis of dyslexia and handedness on our observed associations.

Conclusions

The present family-based and case-control association studies in our Chinese Han populations provide further evidence for the role of BAIAP2 in the predisposition to ADHD, especially ADHD-I. Further studies should investigate the involvement of hemispheric asymmetry genes modulating the difference of left-right hemisphere in ADHD and related cognition.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ADHD-I:

-

ADHD predominantly inattentive type

- ADHD-HI:

-

ADHD predominantly hyperactive/impulsive type

- ADHD-C:

-

ADHD combined type

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- CDIS:

-

Clinical Diagnostic Interview Scale.

References

Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, Sklar P: Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005, 57: 1313-1323. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.024.

Renteria ME: Cerebral asymmetry: a quantitative, multifactorial, and plastic brain phenotype. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2012, 15: 401-413. 10.1017/thg.2012.13.

Oertel-Knochel V, Linden DE: Cerebral asymmetry in schizophrenia. Neuroscientist. 2011, 17: 456-467. 10.1177/1073858410386493.

Lo YC, Soong WT, Gau SS, Wu YY, Lai MC, Yeh FC, Chiang WY, Kuo LW, Jaw FS, Tseng WY: The loss of asymmetry and reduced interhemispheric connectivity in adolescents with autism: a study using diffusion spectrum imaging tractography. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 192: 60-66. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.09.008.

Gilliam M, Stockman M, Malek M, Sharp W, Greenstein D, Lalonde F, Clasen L, Giedd J, Rapoport J, Shaw P: Developmental trajectories of the corpus callosum in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 69: 839-846. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.024.

Rodriguez A, Kaakinen M, Moilanen I, Taanila A, McGough JJ, Loo S, Jarvelin MR: Mixed-handedness is linked to mental health problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010, 125: e340-e348. 10.1542/peds.2009-1165.

Wang YH, Wang YF, Zhou XL: [Hemispheric asymmetry of conflict control in two subtypes of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2007, 39: 266-270.

Chan E, Mattingley JB, Huang-Pollock C, English T, Hester R, Vance A, Bellgrove MA: Abnormal spatial asymmetry of selective attention in ADHD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009, 50: 1064-1072. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02096.x.

Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ: Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 61: 1361-1369. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.011.

Makris N, Biederman J, Valera EM, Bush G, Kaiser J, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ: Cortical thinning of the attention and executive function networks in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2007, 17: 1364-1375. 10.1093/cercor/bhl047.

Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Blumenthal J, Lerch JP, Greenstein D, Clasen L, Evans A, Giedd J, Rapoport JL: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007, 104: 19649-19654. 10.1073/pnas.0707741104.

Shaw P, Lalonde F, Lepage C, Rabin C, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, Greenstein D, Evans A, Giedd JN, Rapoport J: Development of cortical asymmetry in typically developing children and its disruption in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009, 66: 888-896. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.103.

Schrimsher GW, Billingsley RL, Jackson EF, Moore BR: Caudate nucleus volume asymmetry predicts attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptomatology in children. J Child Neurol. 2002, 17: 877-884. 10.1177/08830738020170122001.

Vance A, Silk TJ, Casey M, Rinehart NJ, Bradshaw JL, Bellgrove MA, Cunnington R: Right parietal dysfunction in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, combined type: a functional MRI study. Mol Psychiatry. 2007, 12: 826-832. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001999. 793

Sun T, Patoine C, Abu-Khalil A, Visvader J, Sum E, Cherry TJ, Orkin SH, Geschwind DH, Walsh CA: Early asymmetry of gene transcription in embryonic human left and right cerebral cortex. Science. 2005, 308: 1794-1798. 10.1126/science.1110324.

Ribasés M, Bosch R, Hervas A, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Sanchez-Mora C, Bielsa A, Gastaminza X, Guijarro-Domingo S, Nogueira M, Gomez-Barros N: Case-control study of six genes asymmetrically expressed in the two cerebral hemispheres: association of BAIAP2 with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2009, 66: 926-934. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.024.

Lesch KP, Timmesfeld N, Renner TJ, Halperin R, Roser C, Nguyen TT, Craig DW, Romanos J, Heine M, Meyer J: Molecular genetics of adult ADHD: converging evidence from genome-wide association and extended pedigree linkage studies. J Neural Transm. 2008, 115: 1573-1585. 10.1007/s00702-008-0119-3.

Ouchi Y, Kubota Y, Kuramasu A, Watanabe T, Ito C: Gene expression profiling in whole cerebral cortices of phencyclidine- or methamphetamine-treated rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005, 140: 142-149. 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.07.011.

Toma C, Hervas A, Balmana N, Vilella E, Aguilera F, Cusco I, Del CM, Caballero R, De Diego-Otero Y, Ribases M: Association study of six candidate genes asymmetrically expressed in the two cerebral hemispheres suggests the involvement of BAIAP2 in autism. J Psychiatr Res. 2011, 45: 280-282. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.001.

Franke B, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Buitelaar J, Bau CH, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Mick E, Grevet EH, Johansson S, Haavik J: The genetics of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults, a review. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, 17: 960-987. 10.1038/mp.2011.138.

Barkley R: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. 1998, New York: Guilford, 2

Yang L, Wang Y, Qian Q, Gu B: Primary exploration of the clinical subtype of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Chinese children. Chin J Psychiatr. 2001, 34: 204-207.

Yang L, Wang YF, Qian QJ, Biederman J, Faraone SV: DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD in a Chinese outpatient sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004, 43: 248-250. 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00004.

Guan L, Wang B, Chen Y, Yang L, Li J, Qian Q, Wang Z, Faraone SV, Wang Y: A high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism screen of 23 candidate genes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: suggesting multiple susceptibility genes among Chinese Han population. Mol Psychiatry. 2009, 14: 546-554. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002139.

Livak KJ: Allelic discrimination using fluorogenic probes and the 5’ nuclease assay. Genet Anal. 1999, 14: 143-149. 10.1016/S1050-3862(98)00019-9.

Liu L, Guan LL, Chen Y, Ji N, Li HM, Li ZH, Qian QJ, Yang L, Glatt SJ, Faraone SV: Association analyses of MAOA in Chinese Han subjects with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: family-based association test, case-control study, and quantitative traits of impulsivity. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011, 156B: 737-748.

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 263-265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457.

Nyholt DR: A simple correction for multiple testing for SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74: 765-769. 10.1086/383251.

Wang B, Wang Y, Zhou R, Li J, Qian Q, Yang L, Guan L, Faraone SV: Possible association of the alpha-2A adrenergic receptor gene (ADRA2A) with symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006, 141B: 130-134. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30258.

Cho SC, Kim JW, Kim BN, Hwang JW, Park M, Kim SA, Cho DY, Yoo HJ, Chung US, Son JW: Possible association of the alpha-2Aadrenergic receptor gene with response time variability in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008, 147B: 957-963. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30725.

Association AP: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edition. (DSM-IV). 1994, American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC

Milich R, Balentine A, Lynam D: ADHD combined type and ADHD predominantly inattentive type are distinct and unrelated disorders. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2001, 8: 463-488. 10.1093/clipsy.8.4.463.

Diamond A: Attention-deficit disorder (attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder without hyperactivity): a neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (with hyperactivity). Dev Psychopathol. 2005, 17: 807-825.

Tannock R: Rethinking ADHD and LD in DSM-5: proposed changes in diagnostic criteria. J Learn Disabil. 2013, 46: 5-25. 10.1177/0022219412464341.

Qian Q, Wang Y, Zhou R, Li J, Wang B, Glatt S, Faraone SV: Family-based and case-control association studies of catechol-O-methyltransferase in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder suggest genetic sexual dimorphism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2003, 118B: 103-109. 10.1002/ajmg.b.10064.

Li J, Wang Y, Zhou R, Zhang H, Yang L, Wang B, Khan S, Faraone SV: Serotonin 5-HT1B receptor gene and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Chinese Han subjects. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005, 132B: 59-63. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30075.

Li J, Wang Y, Zhou R, Zhang H, Yang L, Wang B, Faraone SV: Association between polymorphisms in serotonin 2C receptor gene and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Han Chinese subjects. Neurosci Lett. 2006, 407: 107-111. 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.022.

Li J, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhou R, Zhang H, Yang L, Wang B, Faraone SV: The serotonin 5-HT1D receptor gene and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Chinese Han subjects. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006, 141B: 874-876. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30364.

Sengupta SM, Grizenko N, Thakur GA, Bellingham J, DeGuzman R, Robinson S, TerStepanian M, Poloskia A, Shaheen SM, Fortier ME: Differential association between the norepinephrine transporter gene and ADHD: role of sex and subtype. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012, 37: 129-137. 10.1503/jpn.110073.

Smalley SL, Loo SK, Yang MH, Cantor RM: Toward localizing genes underlying cerebral asymmetry and mental health. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005, 135B: 79-84. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30141.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81071109, 81301171), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 program 2014CB846104), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author’s declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LZH and QQJ designed the study. LL, SL, LZH and LHM participated in data collection and experiments. LL, LZH and WLP participated in the statistical analyses and interpreted the results. LL, SL and QQJ drafted the manuscript. WYF supervised the whole study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Lu Liu, Li Sun contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Sun, L., Li, ZH. et al. BAIAP2 exhibits association to childhood ADHD especially predominantly inattentive subtype in Chinese Han subjects. Behav Brain Funct 9, 48 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-9-48

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-9-48