ABSTRACT

Background

Dopamine receptor D 4 (DRD4) polymorphisms have been associated with a number of psychiatric disorders, but little is known about the mechanism of these associations. DNA methylation is linked to the regulation of gene expression and plays a vital role in normal cellular function, with abnormal DNA methylation patterns implicated in a range of disorders. Recent evidence suggests DNA methylation can be influenced by cis-acting DNA sequence variation, that is, DNA sequence variation located nearby on the same chromosome.

Methods

To investigate the potential influence of cis-acting genetic elements within DRD4, we analysed DRD4 promoter DNA methylation levels in the transformed lymphoblastoid cell-line DNA of 89 individuals (from 30 family-trios). Five SNPs located +/− 10kb of the promoter region were interrogated for associations with DNA methylation levels.

Results

Four significant SNP associations were found with DNA methylation (rs3758653, rs752306, rs11246228 and rs936465). The associations of rs3758653 and rs936465 with DNA methylation were tested and nominally replicated (p-value < 0.05) in post-mortem brain tissue from an independent sample (N = 18). Interestingly, the DNA methylation patterns observed in post-mortem brain tissue were similar to those observed in transformed lymphoblastoid cell line DNA.

Conclusions

The link reported between DNA sequence and DNA methylation offers a possible functional role to seemingly non-functional SNP associations. DRD4 has been implicated in several psychiatric disease phenotypes and our results shed light upon the possible mode of action of SNP associations in this region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

DRD4, which encodes a G-protein-coupled dopamine receptor[1], has been widely implicated in the etiology of neuropsychiatric disease. Genetic associations have been reported between DRD4 and ADHD[2–6], anorexia[7], schizophrenia[8, 9], depression[10, 11], obesity[12], addiction[13] and personality disorders[14]. Although some of these genetic associations are supported by evidence of altered DRD4 expression in specific diseases[11, 15, 16], the mechanism by which DRD4 polymorphisms influence behaviour remains unknown. Epigenetic functions may offer some explanation. Epigenetics refers to the reversible regulation of various genomic functions mediated through partially stable modifications of DNA and histone codes, excluding DNA sequence changes. Epigenetic processes, including histone modification and DNA methylation, are intrinsically connected to gene expression, allowing the regulation of gene function through non-mutagenic means[17]. The methylation of CpG dinucleotides, which are overrepresented in the promoter regions of many genes, acts to obstruct cells’ transcriptional machinery and silences gene expression. Correct control of DNA methylation is vital to normal cellular function, and DNA methylation dysfunction has been linked to a number of human pathologies[18, 19], including complex neuropsychiatric phenotypes such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder[20]. Though stochastic factors have been implicated[21], there is growing evidence for the importance of both environmental and genetic factors in the influence of DNA methylation.

Studies of twins suggest greater variability in the DNA methylation patterns of dizygotic (DZ) twins relative to monozygotic (MZ) twins, and heritability estimates of 0.20-0.97 have been generated for DNA methylation levels within various genomic regions[22, 23]. A SNP in MTHFR – the gene encoding 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase which is involved in the maintenance of DNA methylation patterns – has been linked to global DNA methylation levels[24, 25]. Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated cis-acting genetic associations with DNA methylation in humans, chimpanzees and mice[20, 26–34]. Crucially, as these genetic associations with DNA methylation levels have also been shown to correlate with levels of gene expression[33–36], they could represent the mechanism behind allele-specific gene expression, which has been commonly reported throughout the genome[37–40].

A function for previously unexplained genetic associations may therefore lie in the connection between DNA methylation and DNA sequence. If this is the case, further investigation of such markers might involve assessing their influence over local DNA methylation patterns. Yet several studies of DNA methylation report contradictory findings, indicating that the importance of genetic factors may vary across genomic regions, tissues and environments[23, 41, 42]. Thorough analysis in relevant tissues is therefore necessary to draw conclusions about any one gene of interest.

In the present study, we assess the potential influence of cis-acting genetic polymorphisms in mediating DNA methylation at 9 CpG sites across the DRD4 promoter region, using lymphoblastoid cell-lines from a familial sample, and post-mortem brain tissue from an independent set of individuals.

Methods

Samples

CEPH

We obtained 89 high-quality Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) genomic DNA samples extracted from transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines (Coriell Institute for Medical Research, NJ, USA). All samples were tested for degradation and quantified in triplicate using fluorimetry, employing PicoGreen® dsDNA quantitation reagent (Cambridge Bioscience, UK). Aliquots of each sample were diluted 1:5 with TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA) to a working concentration of 50 ng/μl.

Brain samples

Post-Mortem brain samples were obtained from the 18 individuals archived in the MRC London Brainbank for Neurodegenrative Disease (Maudsley Brain Bank, Department of Neuropathology, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK). Brain tissue samples from normal (N = 7; 2 females and 5 males) and Alzheimer’s patients (N = 11; 6 females and 5 males) were used, with agonal states including: Bronchopneumonia, cardiac failure, hypertension, Pulmonary Embolus, Sideroblastic anaemia, coronary occlusion, carcinoma of left kidney, Myocardial Infarction and Ischemic heart disease. Tissue was obtained from multiple brain regions from each patient: striatum, cerebellum, mid-brain, superior frontal gyrus (SFG) and superior temporal gyrus (STG). Data from the Allen Brain Atlas showed DRD4 to be expressed in these tissues (Allen Brain Atlas Resources [Internet]. Seattle (WA): Allen Institute for Brain Science. ©2009. Available from:http://www.brain-map.org). Tissue samples were between 0.5-1g and stored at −70°C, prior to use. Total DNA was prepared from homogenized tissue using the Qiagen Allprep DNA mini kit.

DNA methylation analysis

Bisulfite-PCR primers spanning a region in the DRD4 promoter were designed using the online Sequenom EpiDesigner software (http://www.epidesigner.com). Sodium bisulfite treatment was performed on 375 ng of each CEPH sample using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, CA, USA) following the manufacturers’ standard protocol. The DNA of all 89 individuals was bisulfite converted in the same 96-well plate, with fully-methylated (a methylation level of 100%) and unmethylated DNA (0% methylation) samples included as assay controls. Bisulfite-PCR amplification was conducted using Hot Star Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, UK) and cycling conditions of 45 cycles with an annealing temperature of 56°C. The primers (F: GGGATTTTTTGTTTAGGGTTAGAGG, R: CACCCTAATCCACCTAATATCTAACA) amplified the region chr11:626,509-626,904, assessing 19CpG units (32 CpG sites). DNA methylation analysis was conducted using the Mass-spectrometry-based Sequenom EpiTYPER system (Sequenom Inc, CA, USA), as described previously[43, 44]. The entire experiment, from sodium bisulfite treatment onwards, was subsequently repeated in duplicate to control for technical variation.

To optimise reliability, the data produced were subject to a number of quality control measures. CpG site-containing fragments with a mass outside the range measurable by the Sequenom Epi-Typer system were excluded from further analyses. CpG site-containing fragments with equal or overlapping masses – making them irresolvable by mass spectrometry – were also excluded. CpG site-containing fragments whose measurement was potentially confounded by single nucleotide polymorphisms according to dbSNP build 130 were also discarded. This included fragments containing SNPs which had either been shown to effect populations of European ancestry, or had not yet been tested in such populations. Fragments whose enzyme cut-sites could be affected by SNPs were also excluded. As bisulfite treatment converts cytosines to thymines, fragments containing a C/T SNP on the assayed strand were not excluded, unless this SNP was within a CpG position. Finally, CpG site-containing fragments with >33.33% missing data were excluded. Additional file1 details the exclusions. To minimize technical variability, the remaining methylation data were averaged across the two replicates (the average correlation between the first and second round DNA methylation levels across the nine CpG units was 0.81). All subjects had < 25% missing DNA methylation data. The mean of the DNA methylation values for all CpG sites was calculated in order to gauge the average DNA methylation level in each subject.

SNP Genotyping

SNP genotypes for the extensively investigated CEPH sample (see[45] for further description) were downloaded from the HapMap website on April 8th 2009 (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ - HapMap Rel 27 Phase II + III, Feb 09, NCBI 36 assembly, dbSNP b126). Genotypes for SNPs within 10kb up- and downstream of the DNA methylation-assayed region were downloaded. 6 SNPs with an MAF <0.05 were excluded from the analysis. The remaining SNP genotypes for the 89 individuals within our sample were input into Haploview, where the ‘tagger’ function was used, with an r2 threshold of 0.8, to select 5 SNPs offering optimum coverage (rs11246221, rs3758653, rs752306, rs11246228, rs936465) of the region[46]. All SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium at the p > 0.01 level. Figure1 graphically depicts the DRD4 gene region investigated.

Positional overview of DRD4 region investigated for SNP associations with DNA methylation. White boxes = exons; Black box = region assessed for DNA methylation. Diagram created using data from UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and HapMap (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

The significant associations of two SNPs – rs3758653 and rs936465 – were tested for replication in the 18 Maudsley Brain Bank samples. The SNPs were genotyped via restriction enzyme digestion of PCR products, followed by size descrimination using gel electrophoresis. The primers CCCTCCACTCCAGGCCTCCC and CCTCCATTCCCTCCGGCCCA were used to amplify a 347bp region surrounding rs3758653, which was then digested using EcoRI according to the manufacturer’s instructions. EcoRI cuts the PCR product only if the C allele is present. The primers GCTGCCACCCTACCCCAGGT and GCACTGGGCTGGGCCTGAAC were used to amplify a 203bp region surrounding rs936465, which was then digested with Hpy166II according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Hpy166II selectively cuts the PCR product if the G allele is present on the genomic + strand. Both SNPs had an MAF > 0.05 and were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium at the p > 0.01 level.

Statistical Analyses

The Sequenom Epityper system measures DNA methylation levels as a proportion: 0 (unmethylated) to 1 (fully-methylated). The DNA methylation data was therefore bounded by 0 and 1, and CpG sites with average methylation levels close to these boundaries had a truncated variance. To overcome the problem of skewed variance, the DNA methylation data were arcsine transformed. The data were then normalised using a Van der Waerden transformation and standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Sex was not associated with DRD4 DNA methylation and so was not controlled for in our analyses. Each SNP was tested for association with the average DNA methylation level across all CpGs measured in the CEPH sample, using linear mixed effects models in R[47]. SNP genotype was entered as a fixed effect into the model. As the sample consisted of trios, the genetic relatedness between mother and offspring, and father and offspring, was controlled for as a random effect in the model. We were also able to control for the environment shared by each nuclear family. Unfortunately, our sample size was too small to accurately test for population stratification, however, as our sample consisted of CEPH individuals of European ancestry, and as all SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, we would not expect significant population stratification. As the SNPs were correlated, we used Li and Ji’s method to estimate the effective number of SNPs tested (MeffLi[48]; calculated athttp://gump.qimr.edu.au/general/daleN/SNPSpD/[49]), followed by the Bonferroni method to correct for multiple testing. SNPs exhibiting an association with overall DNA methylation levels were then tested for association with each individual CpG unit within a region. Effect sizes were estimated from Ns and Chi2 values using an online Effect Size Calculator (http://myweb.polyu.edu.hk/~mspaul/calculator/calculator.html).

For the post-mortem brain samples, the DRD4 DNA methylation data were transformed and standardized using the methods described above. Sex and Alzheimer’s status were not associated with DRD4 DNA methylation and so were not controlled for in our analyses. rs3758653 and rs936465, the two strongest associations, were tested for association with average DNA methylation across all CpGs in each available brain tissue type using linear regression in R. Nominally significant associations were investigated further by testing the SNP’s association with individual CpG sites.

Power

Power was estimated using the Genetic Power Calculator[50]. Under the additive association model used, at the p < 0.05 level our sample of 89 individuals from 30 CEPH trios had 80% power to detect a causal variant of 20% allele frequency and 9.6% effect size; and a marker in linkage disequilibrium (D’ = 0.8) with a causal variant of 20% allele frequency and 15.1% effect size. Our sample of 18 post-mortem brain samples had 80% power to detect a causal variant of 20% allele frequency and 41.5% effect size; and a marker in linkage disequilibrium (D’ = 0.8) with a causal variant of 20% allele frequency and 64.8% effect size.

eQTL assessment

SNPs demonstrating significant associations with DNA methylation in the CEPH sample were assessed for eQTL status using SCAN (http://www.scandb.org)[51]. This online resource contains association p-values between genotype and expression data generated from the transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines of CEPH and YRI (Yoruba subjects from Ibadan, Nigeria) subjects included in the HapMap project[45].

Results

SNP associations with average DNA methylation levels

Figure1 graphically depicts the gene region investigated in this study. The mean DNA methylation level across this region within our CEPH transformed lymphoblastoid cell line sample was 0.61, and the standard deviation was 0.13. Table 1 displays the results of SNP association analyses of the average DRD4 DNA methylation level. The relatedness of the CEPH sample was controlled for in the analyses. Mean DNA methylation values across all CpGs were used, however, the first principal component generated from principal components analysis produced similar results (results not shown). Significant SNP associations are represented in Figure2, with average DNA methylation plotted against genotype. 4 out of 5 investigated SNPs showed significant associations with average DNA methylation (rs3758653: N = 81; d.f. = 1; Chi2 = 12.02; P-value = 0.001, rs752306: N = 81; d.f. = 1; Chi2 = 6.78; P-value = 0.009; rs11246228: N = 81; d.f. = 1; Chi2 = 8.67; P-value = 0.003, rs936465: N = 89; d.f. = 1; Chi2 = 10.61; P-value = 0.001). The effect sizes of these associations were substantial – with rs3758653, rs752306, rs11246228 and rs936465 respectively accounting for 14.8%, 8.4%, 10.7% and 11.9% of the variance in average DNA methylation across the DRD4 region in our sample – although the absolute differences in DNA methylation values across genotype groups were small to modest. Although the ranges of DNA methylation shown in Figure2 are distinct for opposing homozygote groups, both groups overlap with the heterozygote group at all SNPs. The associations remained significant after Bonferroni correction for the 4 effective SNP tests conducted (MeffLi)[48]. As the sample contained only one TT homozygote at rs752306 the TT and CT groups were collapsed for the association analyses. When the true genotypes were used the association remained nominally significant (N = 81; d.f. = 1; Chi2 = 9.45; P-value = 0.002).

Significant SNP associations with average DNA methylation levels in the DRD4 gene region. Average percentage DNA methylation plotted by genotype at associated SNPs. Thick black lines represent group mean. Whiskers mark one standard deviation from the mean. As our sample contained only one TT homozygote at rs752306, we collapsed it into the heterozygote groups for analysis.

Figure3 displays the LD pattern between the 5 DRD4 SNPs tested in our sample. The four extra SNPs whose associations were captured (according to the Haploview ‘tagger’ function at r2 > 0.8) are also included in Figure3. The high LD shown between rs11246226, rs11246228, rs7395429, rs936465, rs4331145 and rs11246234 suggests that the significant associations of rs11246228 and rs936465 (and by proxy, the four other SNPs) with DNA methylation are likely to reflect the same effect. As the CEPH population has been extensively genotyped, one of these SNPs could be the influential variant. As rs3758653 and rs752306 exhibit generally weaker LD relationships, they may reflect independent effects. When the effects of rs3758653 and rs936465 are considered together, the association with average DRD4 DNA methylation is stronger (N = 81; d.f. = 2; Chi2 = 16.38; P-value = 2.79E-04), further suggesting the effects of rs3758653 and rs936465 may be independent. As might be expected from Figure3, adding rs752306 and rs11246228 does not further increase the strength of the association (N = 81; d.f = 4; Chi = 18.79; P-value = 0.001). Similarly, haplotype analyses of rs3758653, rs752306, rs11246228 and rs936465 in UNPHASED[24] also indicated independence in the effects of rs3758653 and rs936465, with rs752306 and rs11246228 exerting no extra effects (data not shown).

As one might expect SNPs associated with DNA methylation to also show associations with gene expression, the four significant cis SNP associations were investigated further using the online tool SCAN, which contains p-values from association tests of genotype and expression data from the transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines of CEPH and YRI HaPMaP subjects[51]. No evidence for cis effects on gene expression was found. As SCAN only returns information on genetic associations with a significance levels of p < 0.0001, it is possible that weaker associations were present, however, the lack of strong associations with gene expression raises questions about the function of the SNP associations identified.

Many CpG sites were removed from this study during the stringent quality control process. Some of the CpG units excluded from the analysis of the DRD4 region are of interest because the existence of CpG sites depends on SNP genotypes. CpG site 29 on CpG unit 28.29 may be affected in this way by rs12720379 genotype. rs3758653 and rs752306 showed significant associations with DNA methylation at CpG unit 28.29. In most cases the correlations of CpG unit 28.29 with those showing strong SNP associations in the initial analyses of the DRD4 region are significant and modest (0.23-0.41). Though rs12720379 is an unvalidated SNP which has yet to be tested in a sample of European ancestry, its influence over the presence of a CpG site, and therefore the presence of DNA methylation, can not be ruled out. Neither, therefore, can its possible role in the significant SNP associations reported here.

SNP associations with individual CpG units in the DRD4 gene region

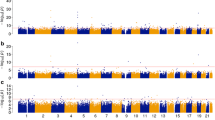

We explored the 4 significant SNP associations with average DRD4 methylation levels further. Table 2 contains p-values from the association analyses of rs3758653, rs752306, rs11246228 and rs936465 with DNA methylation at individual DRD4 CpG units, and Figure4 plots average DNA methylation levels by genotype group at the 4 associated SNPs. The EpiTyper system was unable to resolve all CpG sites, and so while some of the measured CpG units refer to a single CpG site, many reflect average levels of DNA methylation across multiple CpG sites. The similar patterns of association seen between rs11246228 and rs936465 reflect the modest LD between these two SNPs shown in Figure3. The significant associations of rs11246228 and rs936465, as well as of rs3758653, with CpG units 12.13.14, 15.16.17, 21.22.23, 36 and 37.38 reflect the modest correlations between DNA methylation levels across these sites – shown in Figure5’s heatmap displaying the similarities in DNA methylation levels across the measured DRD4 region.

Average percentage DNA methylation across CpG sites in the DRD4 region by genotype groups at 4 associated SNPs. Error bars denote standard deviation. * = significant associations at the p < 0.05 level. Though association analyses were conducted on arcsine transformed data, the true proportion of methylation observed is plotted here. The one homozygous TT subject at rs752306 within our sample was collapsed with the heterozygote group in association analyses.

Association of rs3758653 and rs936465 with DRD4 DNA methylation in post-mortem brain samples from five brain regions

DRD4 is known to be expressed widely in the brain[52](Allen Brain Atlas Resources [Internet]. Seattle (WA): Allen Institute for Brain Science. ©2009. Available from:http://www.brain-map.org). As they appeared to represent independent effects, we tested the association of rs3758653 and rs936465 with DRD4 DNA methylation for replication within a sample of post-mortem brain tissue from 5 brain regions: striatum, mid-brain, cerebellum, superior temporal gyrus (STG) and superior frontal gyrus (SFG). Average levels of DNA methylation in the DRD4 region in our sample were as follows: Striatum mean = 0.52, s.d = 0.06; Mid-brain mean = 0.48, s.d = 0.05; Cerebellum mean = 0.52, s.d = 0.06, STG mean = 0.54, s.d = 0.03, SFG mean = 0.56, s.d = 0.06. The SNP-association results are given in Table 3. One-tailed p-values are provided as we expected effects in the same direction as was observed in the CEPH transformed lymphoblastoid cell line DNA. Of the 10 association results, 8 followed the same direction of effect as the original SNP associations. Nominally significant associations (p < 0.05) were found between rs3758653 and SFG DNA methylation (N = 9; d.f. = 1 and 7; F = 6.51; r2 = 0.45; P-value = 0.017), and between rs936465 and Mid-brain (N = 9; d.f. = 1 and 7; F = 6.51; r2 = 0.44; P-value = 0.017) and STG DNA methylation (N = 12; d.f. = 1 and 10; F = 6.31; r2 = 0.39; P-value = 0.015). Again, the effect sizes were large, with the SNPs accounting for 39-45% of the variation in DNA methylation (rs3758653: Allele A=C, Allele B =T; rs936465: Allele A=C, Allele B = G. STG= Singular Temporal Gyrus; SFG = Singular Frontal Gyrus); however the absolute differences in DNA methylation were small to moderate, the sample size was small and the associations did not remain significant after Bonferroni correction for the 10 tests conducted. Although analyses utilized transformed data, the true DNA methylation levels are given here. Where only one homozygote was available, this subject was combined with the heterozygotes for analyses. The one rs3758653 heterozygote with SFG methylation data was combined with the TT homozygote group for analyses. One-tailed p-values are provided.

Figures 6 and7 display the nominally significant associations of rs3758653 and rs936465 with average DRD4 DNA methylation in post-mortem brain tissue, as well as the associations of these SNPs with individual CpG sites within the DRD4 region. Comparison with data from the CEPH sample indicates not only a similar pattern of association results, but also a similar pattern of DNA methylation levels across the DRD4 CpG sites.

DRD4 percentage DNA methylation levels in CEPH transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and post-mortem Singular Frontal Gyrus tissue (SFG). a) Average DRD4 DNA methylation levels plotted by rs3802971 genotype b) DNA methylation levels across individual DRD4 CpG sites plotted by rs3802971 genotype group. * = significant associations at the p < 0.05 level. Though arcsine transformed data were used in analyses, the true proportion of DNA methylation observed is plotted here. The one heterozygous subject in the post-mortem brain tissue sample was combined with the TT homozygotes for analyses.

DRD4 percentage DNA methylation levels in CEPH transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and post-mortem Mid-brain and Singular Temporal Gyrus tissue (STG). a) Average DRD4 DNA methylation levels plotted by rs936465 genotype b) DNA methylation levels across individual DRD4 CpG sites plotted by rs936465 genotype group. * = significant associations at the p < 0.05 level. Though arcsine transformed data were used in analyses, the true proportion of DNA methylation observed is plotted here. The one subject with available mid-brain DNA methylation data who was GG homozygous at rs936465 was combined with the heterozygotes for analyses.

Discusion

Our investigation uncovered significant SNP associations with DNA methylation levels in the DRD4 promoter, which were replicated at a nominal level of significance (p < 0.05) in an independent sample of post-mortem brain tissue. As with the majority of genetic effects identified in previous studies, these SNP associations occurred in cis[20, 26–32]. As cis-acting genetic influence over DNA methylation has been observed throughout the genome, it may account for many previously unexplained genetic associations. Though we did not analyse trans- acting SNPs in the present study, trans genetic effects are also likely to be important[26, 35].

The greatest group difference in DNA methylation was 16%, between the two rs3758653 homozygote groups. At this stage in our understanding, the functional relevance of these small changes in DNA methylation is unknown. If one is attempting to find an influential locus of large effect, substantial changes in DNA methylation levels may be expected. However, as most complex phenotypes are now thought to be influenced by a myriad of factors of small effect[53, 54], more subtle differences in DNA methylation levels may be important. Our knowledge is still very limited, but as a ~20% difference in DNA methylation has been previously shown to associate with a 2-fold change in gene expression[35, 55], or even to bring about the presence or complete absence of gene expression across various tissues[56], it is likely that individual differences in phenotypic outcome will be cumulatively influenced by many small differences in the epigenetic, and consequently the transcriptomic, landscape. Detecting genetic influences over even more modest individual differences in DNA methylation than observed here will require far larger samples.

It is likely that cis-acting DNA effects on DNA methylation are more important in some genomic regions than in others[22, 26, 33, 35], and our findings suggest that DRD4 may represent a region in which cis- acting genetic-control commonly occurs. Although previous genomewide association studies of DNA methylation have not reported positive results from the DRD4 region[10, 17, 19], such investigations may be limited in the CpGs and SNPs they were able to investigate by the laboratory platforms used. The DRD4 SNPs tested did not show cis-associations with expression in the SCAN database[51], and although we found DRD4 SNP associations with DNA methylation in our independent replication sample, they did not withstand Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Furthermore, the findings of a recent twin study of the same DRD4-associated region assayed here are inconsistent with those we have reported. Wong et al.’s investigation of DNA methylation in 46 MZ and 45 DZ twins indicated no heritable element was involved[42]. Differences in the sample and tissue types used across the two studies are likely to explain the disparate findings. Additionally, all investigations of this region to date – including the present study – have involved extremely small sample sizes. Future work will require far larger samples in order to draw firm conclusions.

One limitation of this study was the modest size of both the discovery and replication samples. Our discovery sample had 80% power to detect causal QTLs of 9.6% effect size, or markers in linkage disequilibrium (D’ = 0.8) with causal QTLs of 15.1% effect size. As subjects were drawn from the extensively characterized CEPH sample, we were more likely to have access to the genotypes of causal variants. Furthermore, one might expect cis-acting SNPs to show larger effects over local DNA methylation than over complex disease phenotypes. Nonetheless, as DNA methylation levels are likely be subject to the effects of multiple environmental, cis and trans genetic, and also stochastic factors, far smaller effect sizes may be involved than the sample was equipped to detect. Though we excluded SNPs with MAFs below 5%, the MAF of one of the SNPs associated with DNA methylation was lower than 10% (rs752306 - see Table 1), further stretching the power of our sample.

Our replication sample was also limited in size, with the analyses involving the largest N of 13 having only 80% power to detect a causal QTL of 53% effect size. Though we did detect nominal SNP associations, we feel our replication sample was too small to draw final conclusions. Unfortunately, the laboratory techniques used to assess DNA methylation are relatively new and still rapidly developing, and both genetically and epigenetically assessing samples involves considerable cost and labour. Consequently, to date the investigations of genetic influences over DNA methylation have all involved similarly small sample sizes[20, 22, 26, 30, 33, 35, 42]. Wisdom gained from studies of other complex phenotypes dictates that future studies should aim to include far larger sample sizes if they hope to detect the expected small effects[53, 57, 58]. This wisdom can also be applied when interpreting the relatively large effect sizes (8.4-14.8%) we did manage to detect in our small discovery sample, and the even larger effect sizes (39-44%) we observed in our replication sample. Though many significant associations between candidate genes and complex traits have been identified and replicated over the years, the large effect sizes originally reported in discovery samples often fall as sample sizes, and number of replication studies, increase[3]. We would therefore expect the effects found in any future investigations of larger samples to be smaller than those reported here.

Our small sample size also restricted the statistical analyses we were able to perform. Firstly, although we would not expect to find significant population stratification within our CEPH participants, the small sample size did not permit us to test this empirically. Secondly, though we controlled for the effects of genetic relatedness and nuclear family environment in our association analyses, our sample was too small to simultaneously estimate many variance parameters accurately. As a result, in many cases the effect of the family environment could not be reliably distinguished from the effects of genetic relatedness in our sample. Although the influence of the environment over DNA methylation is well documented[59], we predicted that it would be less significant in the transformed lymphoblastoid cell line DNA used here. Indeed, after controlling for genetic relatedness in our analyses, the family environment often showed no additional influence over DNA methylation. Our modest sample size also left us unable to take parent of origin effects into account, which recent computational analyses suggest are prevalent across the genome[60]. The stringent Bonferroni method used for multiple-testing correction in our replication sample may also be seen as a limitation, as the 5 tissues tested came from largely the same participants. However, DNA methylation across the 5 brain regions within individuals was uncorrelated, likely to be in part due to low levels of variation in our sample.

The quantitative DNA methylation data generated using the MALDI-TOF-based Sequenom EpiTyper technique were limited in a number of ways. As Additional File1 demonstrates, due to the position of cut sites, after base-specific RNA cleavage some adjacent CpGs remained on the same fragment[33, 34]. As a result, many of the CpG units assessed – including some of those exhibiting significant SNP associations – consisted of average DNA methylation measurements across several CpG sites. Additional File1 also highlights the exclusion of numerous CpG-containing fragments for a variety of reasons. Since the present study was conducted, R packages such as RSeqMeth[44] and MassArray[61] have been created to assist researchers in designing assays which avoid at least some of this loss of data. Furthermore, an optimal method for examining associations between genetic markers and DNA methylation would examine allele-specific methylation The interpretation of results from future studies might be aided by an approach which uses resources such as SCAN to select known eQTLs for tests of association with DNA methylation levels[51].

The source of the DNA used in our discovery sample represents another possible limitation. The aim of this study was to assess the influence of DNA sequence over DNA methylation in 5 genomic regions. By assessing DNA methylation in the CEPH sample, we had the opportunity to investigate a large number of SNPs at no extra cost to our laboratory. However, comparisons of RNA extracted from transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines to that extracted directly from blood cells have revealed significant differences in gene expression[62]. Moreover, when DNA methylation in lymphoblastoid cell lines from type 1 diabetes patients was compared with that in paired peripheral blood leucocytes, differences were observed in 8% of the genes assessed[63]. The SNP associations identified here may therefore not apply to in vivo DNA methylation levels. Despite this, we nominally replicated the two SNP associations emerging from the analysis of the CEPH sample, in DNA derived from brain tissue. It is also worth noting that Figures 6 and7 indicate very similar patterns of DRD4 DNA methylation in the cell line and brain-tissue derived DNA analysed here. Furthermore, a 2010 study of the exact DRD4 region studied here found similar levels of methylation in DNA extracted from buccal swabs[42], suggesting that the results of DNA methylation analyses in transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines may be relevant in vivo.

Future investigations will benefit from an approach similar to that used in Schalkwyk et al.’s 2010 study, which assesses the effects of different alleles within the same individual[35, 64]. This enables a test of SNP association against a background controlled entirely for all environmental and other genetic factors, and unlike our approach, in heterozygotes at least it can expressly identify DNA methylation differences across the two separate DNA strands. As none of the SNPs identified in our study are known to effect the expression of proximal genes, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the effect of the associations with DNA methylation that we have observed. The interpretation of results from future studies might be aided by an approach which uses resources such as SCAN to select known eQTLs for tests of association with DNA methylation levels[51].

Although the limitations of transformed lymphoblastoid cell line DNA have been discussed above, and though we did not consider disease phenotypes in our analyses, our findings may have implications for research into DRD4 disease-associations, especially given the nominally significant associations we found in post-mortem brain tissue. DRD4 has been previously linked to a number of psychiatric and behavioural disorders, most notably ADHD[2]. Much of the emphasis has been upon the exon 3 VNTR[3], yet SNPs in the DRD4 promoter have also shown significant associations with ADHD[4, 5], schizophrenia[8, 9] and fibromyalgia[65]. Interestingly, two SNPs tagged in this study have emerged previously in the literature (see Figure3); rs936465 is in LD (r2 of 0.96) with rs4331145, which has been implicated in schizophrenia[9], and rs11246226 (r2 of 0.55), which has been implicated in schizophrenia and fibromyalgia[9, 65]. DNA methylation has been suggested as a mediator of well-known environmental influences over disease phenotypes such as ADHD[59, 66, 67]. Our results suggest that epigenetic processes may mediate previously identified, but as yet unexplained, genetic influences too.

Conclusions

We have reported SNP associations with DNA methylation levels in the DRD4 gene region. Although replication is needed in larger samples, our findings add to the existing literature linking genetic sequence to DNA methylation patterns. DRD4 has been implicated in a number of disease phenotypes, and our results offer a possible mechanism of action for previously unexplained SNP associations in these regions.

References

Van Tol HH, Bunzow JR, Guan HC, Sunahara RK, Seeman P, Niznik HB, Civelli O: Cloning of the gene for a human dopamine D4 receptor with high affinity for the antipsychotic clozapine. Nature. 1991, 350: 610-614. 10.1038/350610a0.

Faraone SV, Mick E: Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010, 33: 159-180. 10.1016/j.psc.2009.12.004.

Li D, Sham PC, Owen MJ, He L: Meta-analysis shows significant association between dopamine system genes and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Hum Mol Genet. 2006, 15: 2276-2284. 10.1093/hmg/ddl152.

Munaf MR, Yalcin B, Willis-Owen SA, Flint J: Association of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene and approach-related personality traits: meta-analysis and new data. Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 63: 197-206. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.006.

Lasky-Su J, Lange C, Biederman J, Tsuang M, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Laird N, Faraone S: Family-based association analysis of a statistically derived quantitative traits for ADHD reveal an association in DRD4 with inattentive symptoms in ADHD individuals. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008, 147: 100-106.

Nikolaidis A, Gray JR: ADHD and the DRD4 exon III 7-repeat polymorphism: an international meta-analysis. Soc Cogn Affect Neur. 2010, 5: 188-193. 10.1093/scan/nsp049.

Bachner-Melman R, Lerer E, Zohar AH, Kremer I, Elizur Y, Nemanov L, Golan M, Blank S, Gritsenko I, Ebstein RP: Anorexia nervosa, perfectionism, and dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4). Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007, 144B: 748-756. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30505.

Okuyama Y, Ishiguro H, Toru M, Arinami T: A genetic polymorphism in the promoter region of DRD4 associated with expression and schizophrenia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999, 258: 292-295. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0630.

Pal P, Mihanovi M, Molnar S, Xi H, Sun G, Guha S, Jeran N, Tomljenovi A, Malnar A, Missoni S: Association of tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms on 8 candidate genes in dopaminergic pathway with schizophrenia in Croatian population. Croatian Medical Journal. 2009, 50: 361-369. 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.361.

Lopez Leon S, Croes EA, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Claes S, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM: The dopamine D4 receptor gene 48-base-pair-repeat polymorphism and mood disorders: a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2005, 57: 999-1003. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.030.

Xiang L, Szebeni K, Szebeni A, Klimek V, Stockmeier CA, Karolewicz B, Kalbfleisch J, Ordway GA: Dopamine receptor gene expression in human amygdaloid nuclei: elevated D4 receptor mRNA in major depression. Brain Res. 2008, 1207: 214-224.

Levitan RD, Masellis M, Lam RW, Kaplan AS, Davis C, Tharmalingam S, Mackenzie B, Basile VS, Kennedy JL: A birth-season/DRD4 gene interaction predicts weight gain and obesity in women with seasonal affective disorder: A seasonal thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006, 31: 2498-2503. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301121.

McGeary J: The DRD4 exon 3 VNTR polymorphism and addiction-related phenotypes: A review. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 2009, 93: 222-229. 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.03.010.

Nemoda Z, Lyons-Ruth K, Szekely A, Bertha E, Faludi G, Sasvari-Szekely M: Association between dopaminergic polymorphisms and borderline personality traits among at-risk young adults and psychiatric inpatients. Behav Brain Funct. 2010, 6: 4-10.1186/1744-9081-6-4.

MeadorWoodruff JH, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Davidson M, Davis KL, Watson SJ: Dopamine receptor transcript expression in striatum and prefrontal and occipital cortex - Focal abnormalities in orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997, 54: 1089-1095. 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830240045007.

Stefanis NC, Bresnick JN, Kerwin RW, Schofield WN, McAllister G: Elevation of D-4 dopamine receptor mRNA in postmortem schizophrenic brain. Molecular Brain Research. 1998, 53: 112-119. 10.1016/S0169-328X(97)00285-4.

Henikoff S, Matzke MA: Exploring and explaining epigenetic effects. Trends in Genetics. 1997, 13: 293-295. 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01219-5.

Hatchwell E, Greally JM: The potential role of epigenomic dysregulation in complex human disease. Trends in Genetics. 2007, 23: 588-595. 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.010.

Jones PA, Baylin SB: The epigenomics of cancer. Cell. 2007, 128: 683-692. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029.

Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, Jia P, Assadzadeh A, Flanagan J, Schumacher A: Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008, 82: 696-711. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008.

Petronis A: Epigenetics and twins: three variations on the theme. Trends in Genetics. 2006, 22: 347-350. 10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.010.

Heijmans BT, Kremer D, Tobi EW, Boomsma DI, Slagboom PE: Heritable rather than age-related environmental and stochastic factors dominate variation in DNA methylation of the human IGF2/H19 locus. Hum Mol Genet. 2007, 16: 547-554. 10.1093/hmg/ddm010.

Kaminsky ZA, Tang T, Wang SC, Ptak C, Oh GHT, Wong AHC, Feldcamp LA, Virtanen C, Halfvarson J, Tysk C: DNA methylation profiles in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 240-245. 10.1038/ng.286.

Friso S, Choi SW, Girelli D, Mason JB, Dolnikowski GG, Bagley PJ, Olivieri O, Jacques PF, Rosenberg IH, Corrocher R: A common mutation in the 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene affects genomic DNA methylation through an interaction with folate status. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99: 5606-5611. 10.1073/pnas.062066299.

Castro R, Rivera I, Ravasco P, Camilo ME, Jakobs C, Blom HJ, De Almeida IT: 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) 677C - > T and 1298A - > C mutations are associated with DNA hypomethylation. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2004, 41: 454-458. 10.1136/jmg.2003.017244.

Zhang D, Cheng L, Badner JA, Chen C, Chen Q, Luo W, Craig DW, Redman M, Gershon ES, Liu C: Genetic Control of Individual Differences in Gene-Specific Methylation in Human Brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2010, 86: 411-419. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.005.

Milani L, Lundmark A, Nordlund J, Kiialainen A, Flaegstad T, Jonmundsson G, Kanerva J, Schmiegelow K, Gunderson KL, Lˆnnerholm G: Allele-specific gene expression patterns in primary leukemic cells reveal regulation of gene expression by CpG site methylation. Genome Res. 2009, 19: 1-11.

Yamada Y, Watanabe H, Miura F, Soejima H, Uchiyama M, Iwasaka T, Mukai T, Sakaki Y, Ito T: A comprehensive analysis of allelic methylation status of CpG islands on human chromosome 21q. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 247-266. 10.1101/gr.1351604.

Zhang Y, Rohde C, Tierling S, Jurkowski TP, Bock C, Santacruz D, Ragozin S, Reinhardt R, Groth M, Walter J: DNA methylation analysis of chromosome 21 gene promoters at single base pair and single allele resolution. PLoS Genetics. 2009, 5: e1000438. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000438.

Zhang Y, Rohde C, Reinhardt R, Voelcker-Rehage C, Jeltsch A: Non-imprinted allele-specific DNA methylation on human autosomes. Genome Biol. 2009, 10: R138-10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-r138.

Kerkel K, Spadola A, Yuan E, Kosek J, Jiang L, Hod E, Li K, Murty VV, Schupf N, Vilain E: Genomic surveys by methylation-sensitive SNP analysis identify sequence-dependent allele-specific DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 904-908. 10.1038/ng.174.

Schilling E, El Chartouni C, Rehli M: Allele-specific DNA methylation in mouse strains is mainly determined by cis-acting sequences. Genome Res. 2009, 19: 2028-2035. 10.1101/gr.095562.109.

Bell JT, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Gaffney DJ, Pique-Regi R, Degner JF, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK: DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome Biol. 2011, 12: R10. 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10.

Pai AA, Bell JT, Marioni JC, Pritchard JK, Gilad Y: A genome-wide study of DNA methylation patterns and gene expression levels in multiple human and chimpanzee tissues. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7: e1001316-10.1371/journal.pgen.1001316.

Schalkwyk LC, Meaburn EL, Smith R, Dempster EL, Jeffries AR, Davies MN, Plomin R, Mill J: Allelic Skewing of DNA Methylation Is Widespread across the Genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010, 86: 196-212. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.014.

Polesskaya OO, Aston C, Sokolov BP: Allele C-specific methylation of the 5-HT2A receptor gene: evidence for correlation with its expression and expression of DNA methylase DNMT1. J Neurosci Res. 2005, 83: 362-373.

Lo HS, Wang Z, Hu Y, Yang HH, Gere S, Buetow KH, Lee MP: Allelic variation in gene expression is common in the human genome. Genome Res. 2003, 13: 1855-1862.

Knight JC: Allele-specific gene expression uncovered. Trends in Genetics. 2004, 20: 113-116. 10.1016/j.tig.2004.01.001.

Bray NJ, Buckland PR, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC: Cis-acting variation in the expression of a high proportion of genes in human brain. Hum Genet. 2003, 113: 149-153.

Gimelbrant A, Hutchinson JN, Thompson BR, Chess A: Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science. 2007, 318: 1136-1140. 10.1126/science.1148910.

Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, Heine-Suner D, Cigudosa JC, Urioste M, Benitez J: Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005, 102: 10604-10609. 10.1073/pnas.0500398102.

Wong CCY, Caspi A, Williams B, Craig IW, Houts R, Ambler A, Moffitt TE, Mill J: A longitudinal study of epigenetic variation in twins. Epigenetics. 2010, 5: 1-11. 10.4161/epi.5.1.10941.

Ehrich M, Nelson MR, Stanssens P, Zabeau M, Liloglou T, Xinarianos G, Cantor CR, Field JK, van den Boom D: Quantitative high-throughput analysis of DNA methylation patterns by base-specific cleavage and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005, 102: 15785-15790. 10.1073/pnas.0507816102.

Coolen MW, Statham AL, Gardiner-Garden M, Clark SJ: Genomic profiling of CpG methylation and allelic specificity using quantitative high-throughput mass spectrometry: critical evaluation and improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: e119-10.1093/nar/gkm662.

The International HapMap C: A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007, 449: 851-861. 10.1038/nature06258.

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 263-265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457.

Bates D, Sarkar D: lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using S4 Classes. R package version. 2006, 95: 221-227. http://www.r-project.org.

Li J, Ji L: Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity. 2005, 95: 221-227. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717.

Nyholt DR: A Simple Correction for Multiple Testing for Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Linkage Disequilibrium with Each Other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74: 765-769. 10.1086/383251.

Purcell S, Cherny SS, Sham PC: Genetic Power Calculator: design of linkage and association genetic mapping studies of complex traits. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 149-150. 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.1.149.

Gamazon ER, Zhang W, Konkashbaev A, Duan S, Kistner EO, Nicolae DL, Dolan ME, Cox NJ: SCAN: SNP and copy number annotation. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26: 259-262. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp644.

Oak JN, Oldenhof J, Van Tol HH: The dopamine D(4) receptor: one decade of research. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000, 405: 303-327. 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00562-8.

Wellcome Trust Case Control C: Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007, 447: 661-678. 10.1038/nature05911.

Lupski JR, Belmont JW, Boerwinkle E, Gibbs RA: Clan genomics and the complex architecture of human disease. Cell. 2011, 147: 32-43. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.008.

Katari S, Turan N, Bibikova M, Erinle O, Chalian R, Foster M, Gaughan JP, Coutifaris C, Sapienza C: DNA methylation and gene expression differences in children conceived in vitro or in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2009, 18: 3769-3778. 10.1093/hmg/ddp319.

Palacios D, Summerbell D, Rigby PWJ, Boyes J: Interplay between DNA Methylation and Transcription Factor Availability: Implications for Developmental Activation of the Mouse Myogenin Gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2010, 30: 3805-3815. 10.1128/MCB.00050-10. Epub ahead of print

Visscher PM: Sizing up human height variation. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 489-490. 10.1038/ng0508-489.

Weedon MN, Lango H, Lindgren CM, Wallace C, Evans DM, Mangino M, Freathy RM, Perry JRB, Stevens S, Hall AS: Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 575-583. 10.1038/ng.121.

Docherty S, Mill J: Epigenetic mechanisms as mediators of environmental risks for psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry. 2008, 7: 500-506. 10.1016/j.mppsy.2008.10.006.

Luedi PP, Dietrich FS, Weidman JR, Bosko JM, Jirtle RL, Hartemink AJ: Computational and experimental identification of novel human imprinted genes. Genome Res. 2007, 17: 1723-1730. 10.1101/gr.6584707.

Thompson RF, Suzuki M, Lau KW, Greally JM: A pipeline for the quantitative analysis of CG dinucleotide methylation using mass spectrometry. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25: 2164-2170. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp382.

Lee JE, Nam HY, Shim SM, Bae GR, Han BG, Jeon JP: Expression phenotype changes of EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines during long-term subculture and its clinical significance. Cell proliferation. 2010, 43: 378-384. 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00687.x.

Brennan EP, Ehrich M, Brazil DP, Crean JK, Murphy M, Sadlier DM, Martin F, Godson C, McKnight AJ, van den Boom D: Comparative analysis of dna methylation profiles in peripheral blood leukocytes versus lymphoblastoid cell lines. Epigenetics: official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2009, 4: 159-164. 10.4161/epi.4.3.8793.

Bock C, Reither S, Mikeska T, Paulsen M, Walter J, Lengauer T: BiQ Analyzer: visualization and quality control for DNA methylation data from bisulfite sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 4067-10.1093/bioinformatics/bti652.

Garcia-Fructuoso FJ, Lao-Villadoniga JI, Santos C, Poca-Dias V, Fernandez-Sola J: Identification of differential genetic profiles in severe forms of fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a population-based genetic association study. Journal of Clinical Research. 2008, 11: 1-24.

Jirtle RL, Skinner MK: Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007, 8: 253-262. 10.1038/nrg2045.

Smith AK, Mick E, Faraone SV: Advances in genetic studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009, 11: 143-148. 10.1007/s11920-009-0022-0.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an award from the London University Central Research Fund and a Royal Society Research Grant. We would like to thank Dr. Nadeem Khan for providing the IOP human brain bank tissue samples. Additionally we acknowledge Kyle Powell for technical assistance with DNA preparations from the postmortem brain samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

SJD generated DNA methylation data, genotyped the replication sample, ran statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. OD and CH assisted in the conception of the project and in statistical analyses. RP, JM and UD assisted in the conception of the project and in drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Docherty, S.J., Davis, O.S.P., Haworth, C.M.A. et al. A genetic association study of DNA methylation levels in the DRD4 gene region finds associations with nearby SNPs. Behav Brain Funct 8, 31 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-8-31

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-9081-8-31