Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non-coding RNAs that inhibit translation of target genes by binding to their mRNAs. The expression of numerous brain-specific miRNAs with a high degree of temporal and spatial specificity suggests that miRNAs play an important role in gene regulation in health and disease. Here we investigate the time course gene expression profile of miR-1, -16, and -206 in mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG), and spinal cord dorsal horn under inflammatory and neuropathic pain conditions as well as following acute noxious stimulation.

Results

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analyses showed that the mature form of miR-1, -16 and -206, is expressed in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Moreover, CFA-induced inflammation significantly reduced miRs-1 and -16 expression in DRG whereas miR-206 was downregulated in a time dependent manner. Conversely, in the spinal dorsal horn all three miRNAs monitored were upregulated. After sciatic nerve partial ligation, miR-1 and -206 were downregulated in DRG with no change in the spinal dorsal horn. On the other hand, axotomy increases the relative expression of miR-1, -16, and 206 in a time-dependent fashion while in the dorsal horn there was a significant downregulation of miR-1. Acute noxious stimulation with capsaicin also increased the expression of miR-1 and -16 in DRG cells but, on the other hand, in the spinal dorsal horn only a high dose of capsaicin was able to downregulate miR-206 expression.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that miRNAs may participate in the regulatory mechanisms of genes associated with the pathophysiology of chronic pain as well as the nociceptive processing following acute noxious stimulation. We found substantial evidence that miRNAs are differentially regulated in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord under different pain states. Therefore, miRNA expression in the nociceptive system shows not only temporal and spatial specificity but is also stimulus-dependent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenously expressed short non-coding RNAs thought to inhibit protein translation through binding to a target complementary mRNA [1–6]. Thus, the encoded genetic information is not only transcribed and translated into proteins but also regulates these processes through miRNA sequence-guided interactions with the related miRNA [2, 7–9]. Expression analysis of miRNAs has been widely used to monitor tissue-specific miRNA expression and regulatory changes in developmental stages, cell types and tissues [1, 10, 11]. Tissue and temporal specificity suggest that miRNAs sequences have an organ and/or cell type-specific function [12–16]. Furthermore, abnormal patterns of miRNA expression have also been found in many disease states where both increased and decreased expression of miRNAs have been described [16, 17]. The first experimental reports addressing the involvement of miRNAs in the nociceptive system clearly indicate that inflammatory muscle pain [18], and peripheral nerve injury [19] modify the expression profile of a number of miRNAs in trigeminal and dorsal root ganglion, respectively. A recent work provided evidence that miRNAs regulate the expression of several transcripts associated with inflammatory pain [20]. Indeed, the nociceptive system is substantially modified in response to tissue damage, inflammation or injury to the nervous system where changes in gene expression patterns are a marked molecular mechanism underlying the development and maintenance of chronic pain [21–25]. Hence, transcriptional changes can dramatically alter the phenotypic profile and function of neurons and glia cells in the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord dorsal horn, where nociceptive messages are primarily released to the central nervous system [21, 22]. However, our understanding on the mechanisms regulating post-transcriptional machinery remains very limited. In the present study we tested the hypothesis that in addition to temporal or spatial-specificity miRNA expression is also stimulus-dependent in the nociceptive system. In the present study the criteria to select four miRNAs were their reported expression in the mouse nervous system [10, 26] and/or their predicted pain-related target genes, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, mitogen activated protein kinase, phospholipase A2, and opioid receptor from in silico investigation [27, 28]. Therefore, we investigated the temporal, spatial and stimulus-dependent specificity of miRNAs by monitoring the time-course expression of miR-1, miR-16, miR-122a, and miR-206 in mouse DRG and spinal cord dorsal horn under inflammatory and neuropathic pain states as well as after acute nociceptive stimulation.

Methods

Animals

Adult Balb/c mice (20-25 g) were housed 4-5 per cage on a 12 hours light/dark cycles (lights on at 6 A.M.) and kept at 25°C ± 1°C. Food and water were available ad libitum. Behavioral experiments were performed between 9 A.M. and 4 P.M. The experimental procedures performed on animals were approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine, University of São Paulo and followed the International Association for the Study of Pain guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals [29].

Chronic inflammatory pain model

Tissue inflammation was produced by injecting 20 μL of CFA-complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) subcutaneously in the dorsal aspect of the left hind-paw whereas mineral oil (Sigma) was used as control. Paw withdrawal thresholds to mechanical stimuli were assessed 12 h, 1, 3 and 7 days post-injection. At the completion of behavioral testing, mice were euthanized. Control animals were euthanized 12 h post-injection.

Neuropathic pain model

Nerve injury was performed in anesthetized mice (ketamine and xylazine, 60 and 8 mg/kg, respectively) by tying a tight ligature with 8-0 silk wire around approximately one-third to one-half of the diameter of the left sciatic nerve [30]. Sham-operated animals had the left sciatic nerve exposed, but not ligated. After surgery nerve-injured animals were randomly separated in 4 groups and the development of tactile stimulus-induced neuropathic pain hypersensitivity was assessed at 1, 3, 7 and 14 days post-injury. By the end of the behavioral assay, mice were euthanized. Sham-operated control animals were euthanized 12 h post-injection.

Axotomy

Animals were anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg), and had the left sciatic nerve transected. A segment of approximately 1 mm was removed and the stumps were tightly ligated with 8-0 silk wire. Sham-operated animals had the sciatic nerve exposed but not sectioned. Nerve-injuried animals were separated in 3 groups and euthanized 1, 3, and 7 days post-lesion. Sham-operated animals were killed 24 hours after surgery. The left L4-L5 DRG and lumbar spinal dorsal horn were harvested immediately after euthanasia and processed for total RNA extraction.

Acute noxious stimulation

Acute pain was induced by subcutaneous injection of capsaicin in the dorsal aspect of the left hindpaw. Two doses of capsaicin were tested, 2 and 10 μg/20 μL. Control animals were injected with vehicle (89.5% saline, 10% ethanol, 0.5% Tween-80). Animals were euthanized 10 minutes post injection and DRG and the lumbar spinal cord dorsal horn dissected out for RNA extraction.

Behavior analysis

Mechanical hypersensitivity was assessed before and after the injection of CFA or nerve injury by measuring the paw withdrawal threshold in response to probing calibrated Semmes-Weinstein monofilaments (von Frey hairs; Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). Animals were placed on an elevated meshed grid which allowed full access to the ventral aspect of the hindpaws. A logarithmic series of 9 filaments were applied to the left hindpaw to determine the threshold stiffness required for 50% paw withdrawal according to the non-parametric method of Dixon [31] as described by Chaplan et al. [32]. This behavioral analysis ensured that all animals selected to the miRNA expression assay developed mechanical hypersensitivity over the entire period of investigation in the inflammatory and neuropathic pain models. In the acute pain model, nocifensive behavior was monitored as time spent biting/licking capsaicin or vehicle-injected paw for 10 min.

Tissue dissection

Animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation and the left DRG (L4-L5) as well as the lumbar (L4-L6) spinal cord were dissected out. Next, the spinal cord was further dissected in PBS (4°C) by removing only the left superior quadrant of the spinal cord. Then, the tissues were rapidly homogenized in Trizol reagent at 4°C and frozen at -80°C for further processing.

Multiplexing reverse transcriptase reaction

Total RNA from DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord was isolated using Trizol® reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacture's instruction. RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf BioPhotometer plus). For multiplexing reverse transcriptase reactions we used TaqMan microRNA Reverse Transcription kit with specific primers for miR-1, -16, -122a, -206, and snoR-202 following protocol provided by the manufacture (Applied Biosystems).

Real-time RT-PCR

To quantify miRNAs by real-time RT- PCR we used TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix, No AmpErase® UNG (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was performed according to the manufacture's standard protocol. PCR primers and probes for amplification of the mouse mature miRNAs were specifically design for miR-1, -16, -122a, -206, and snoR-202 (Applied Biosystems). RT-PCR analysis was performed on an ABI5500HT instrument (ABI Inc.). All reactions were run in duplicate. The relative quantity of each miRNA in the tissues was calculated using the equation RQ = 2-ΔΔCT [33]. SnoR-202 was measured by the same method and remained stable along the tested time period (data not shown). Therefore, snoR-202 was used for normalization as the internal control gene whereas the calibrator was the mean threshold cycle (C T) value for each control group associated with their respective pain model.

Results

We first monitored the mechanical sensitivity at different times after subcutaneous CFA administration, ensuring that all animals selected to the gene expression assays developed tactile mechanical hypersensitivity over the entire period of investigation (Figure 1A). Thereafter, we were able to detect miR-1, -16 and -206, but not miR-122a even after 40 cycles. CFA injection induced a significant downregulation of miR-1, -16 in DRG as early as 12 h persisting until 7 days post-injection (Figure 1B). However, the expression of miR-206 showed an irregular profile being downregulated at days 1 and 7, but returned to normal levels by day 3 post-injection (Figure 1B). On the contrary, in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord the expression of miR-1, -16, and -206 showed a significant increase at day 1, 3 and 7 but not in the initial inflammatory process (Figure 1C).

Expression profile of mature microRNAs in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord during peripheral inflammation. (A) CFA injection induced mechanical hypersensitivity 12 hours, 1, 3 and 7 days post-injection (black bars) compared to the basal values (white bars). Mineral-oil injected mice showed no threshold changes from day 1 to 7 post-injection. (B) In DRG, miR-1 (white bars) and -16 (gray bars) were significantly downregulated under the entire inflammatory period. However, miR-206 (black bars) was down regulated only on day 1 and 7 post-injection. (C) In the spinal dorsal horn there was no change in the early inflammatory process (12 h post-injection) whereas the relative expression of miRs-1, -16 and -206 showed a significant increase at day 1, 3 and 7 post-injection. Bars represent mean ± SEM. # p < 0.001 for CFA injected animals compared to mineral oil injected mice, n = 6 - 8 per group; Student's t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 for each miRNA of the treated group compared to mineral-oil injected animals and euthanized 12 h post-injection (time 0), n = 6-8 per group; Student's t-test.

We next analyzed the detectable levels of the three miRNAs in DRG and the spinal dorsal horn of animals submitted to partial ligation of the sciatic nerve. This model allowed us to monitor the development of tactile stimulus-induced neuropathic pain hypersensitivity. Peripheral nerve lesion induced a marked mechanical allodynia from day 1 to 14 post-injury whereas sham-operated animals showed no change in mechanical sensitivity (Figure 2A). The expression profile of miR-1 in DRG showed no change at day 1 after nerve injury but a significant downregulation at day 3, 7 and 14 post-surgery (Figure 2B). Conversely, miR-16 showed no difference in the expression level over the entire period of study. However, the expression pattern of miR-206 was similar to miR-1. A remarkable downregulation was observed as early as day 1, persisting at days 3, 7 and 14 (Figure 2B). In the spinal cord dorsal horn no change was observed in the expression profile of any miRNAs investigated (Figure 2C). It is well characterized that pain from different origins may induce specific phenotypic changes in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Then, we used another model of neuropathic pain by axotomizing the sciatic nerve. Opposite to the results observed in the partial nerve lesion model, complete peripheral nerve section induced an upregulation of miR-1, -16 and -206 in DRG at days 1, 3 and 7 post-injury (Figure 3A). On the other hand, miR-1 showed a significant decrease in the spinal dorsal horn from day 1 to day 7 whereas no change was observed in the expression of miR-16 and -206 (Figure 3B).

The effect of partial sciatic nerve ligation on miRNA expression in DRG and spinal cord dorsal horn. (A) Mice submitted to nerve lesion developed tactile stimulus-induced hypersensitivity at 1, 3, 7 and 14 days post-surgery (black bars) whereas sham-operated animals (white bars) showed no change on mechanical threshold. (B) In DRG, miR-206 (black bars) was downregulated at all time points investigated whereas miR-1 reduced relative expression (white bars) occurred only after the day 3 post-surgery. No significant change was detected for miR-16 (gray bars). (C) In spinal cord dorsal horn, there was no modification in the expression profile for any miRNA studied. Bars represent mean ± SEM. # p < 0.001 for nerve injured animals compared to sham-operated mice, n = 6 - 8 per group; Student's t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 for each miRNA expression in nerve injuried group compared to sham-operated control animals euthanized 24 h after surgery (time 0), n = 6 - 8 per group, Student's t-test.

Expression profile of microRNAs in DRG and spinal dorsal horn after sciatic nerve axotomy. (A) MiR-1 (white bars) and -206 (black bars) showed a robust upregulation in the dorsal root ganglion whereas miR-16 (gray bars) relative expression also increased, but only on days 1 and 3 post-injury returning to its normal values on day 7 post-nerve lesion. (B) in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, miR-1 was downregulated over the entire period of investigation and no change was observed for miR-16 and -206. Bars represent mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 for each miRNA expression in axotomized group compared to sham-operated control animals euthanized 24 h after surgery (time 0), n = 6 - 8 per group, Student's t-test.

Acute noxious stimulation may also change gene expression, and therefore we evaluated the effect of capsaicin stimulation on miRNAs regulation. Capsaicin was injected at 2 or 10 μg/20 μl in order to investigate whether the stimulus intensity correlates with a specific gene expression pattern. Thus, capsaicin administration induced a concentration-dependent nocifensive response when compared to vehicle injected mice (Figure 4A). Moreover, capsaicin induced a significant upregulation of miR-1 and miR-16, but not miR-206, in DRG (Figure 4B). However, no difference was observed between the two concentrations injected. On the other hand, no significant change was observed in the spinal dorsal horn after injecting the lower dose of capsaicin. In contrast, higher capsaicin dose reduced only miR-206 expression (Figure 4C). Collectively, these observations indicate that miRNA expression is markedly modified by different pain conditions with a high degree of spatial, temporal, and stimulus-dependent specificity.

Effect of acute noxious stimulation on miRNA expression in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal. (A) Capsaicin induced a concentration-dependent nocifensive behavior measured by the time spent licking the injected hindpaw. Control group injected with vehicle showed no alteration on the behavior response. (B) Ten minutes after stimulation, miR-1 (white bars) and -16 (gray bars), but not miR-206 (black bars), showed an increased expression in DRG, however, this upregulation was not concentration-dependent as observed in the behavior test. (C) In the spinal dorsal horn, 2 μg of capsaicin had no effect on miRNAs expression whereas 10 μg induced a dowregulation of miR-206. Bars represent mean ± SEM. # p < 0.001 for comparing different capsaicin-injected doses, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 for capsaicin-injected animals compared to vehicle injected mice, Mann-Whitney U test, n = 6 - 8,. Student's t-test was used for gene expression analysis where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 for capsaicin-injected animals compared to vehicle injected mice, n = 6 - 8 per group.

Discussion

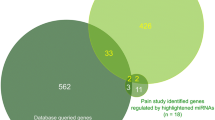

Previous northern blot analysis showed that miR-1, -16 and -206 are expressed in mouse cortex, cerebellum e midbrain [10, 26]. Moreover, in silico studies predict that those miRNAs plus miR-122a target several important pain-related genes (Table 1). Our results indicate that miR-1, -16, and -206, but not miR-122a are also expressed in DRG and the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Moreover, the expression of these miRNAs in the nociceptive system shows spatial and temporal specificity, and a marked stimulus-dependent pattern of regulation. Thus, while miRNA expression in DRG cells promptly responded to nociceptive stimulation, the spinal cord cells were less affected. A robust amount of data have shown that various chronic pain conditions result in a dramatic alteration of gene transcription and protein synthesis in DRG, spinal cord dorsal horn and brain nuclei [21, 34, 35]. These changes include both up and downregulation of neuropeptides, G-protein coupled receptors, growth factors and their receptors, transcription factors as well as a large number of other messenger molecules [21–23, 36]. Although the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation in DRG and spinal dorsal horn under nociceptive and pathological pain remain largely unknown, our results strongly suggest an important role for miRNAs in the activity-dependent cellular plasticity underlying chronic pain. MiRNAs regulate protein synthesis through sequence-guided interactions with the target complementary mRNA blocking the transcription and translation processes [1, 37]. Therefore, changes on miRNA expression following nociceptive stimulation may represent one of the earliest events underlying the phenotypic switch induced by persistent stimulation of nociceptive primary afferents, including both high threshold C- and Aδ-fibers. Over the last few years there has been a rapid and an enormous progress in cataloging hundreds of miRNA genes, determining their expression patterns, and in few cases identifying their regulatory targets [38–40]. Notwithstanding, very few data has been raised on the miRNA expression in the nociceptive system. Bai and collaborators investigated the expression of a number of miRNAs in rat trigeminal ganglion (TG) during inflammatory muscle pain [18]. The authors investigated the time-course expression of miR-10a, -29a, -98, -99a, -124a, -134, -183 following CFA injection into the rat masseter muscle. All tested miRNAs were significantly downregulated within 4 hr after CFA administration whereas at day 12, all tested miRNAs were completely recovered to a level similar to or higher than the basal level. In our mouse model, CFA also induced a sustained down regulation of miR-1 and -16 from 12 hours to 7 days post-injection in DRG. Interestingly, Bai's study reported a fluctuating pattern of expression for some miRNAs (e.g. miR-29a, and -134), switching from downregulation to upregulation and returning to the basal levels again. We have also observed this dynamic pattern of expression in DRG following CFA injection. Thus, miR-206 showed a significant down-regulation on day 1 and 7, but not on day 3 post-injection evidencing the same unsteady pattern of expression during CFA induced inflammation. Similarly to Bai, we found no expression of miR-122, neither in DRG, nor in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Moreover, none of the stimuli applied were able to induce its expression. Aldrich used the spinal nerve ligation model of chronic neuropathic pain to investigate the expression of miR-183 family members (miR-96, -182, and -183) in the rat DRG [19]. The authors observed a significant reduction in expression of these miRNAs in injured DRG neurons 2 weeks after nerve injury. Using the partial sciatic nerve injury model we also observed a sustained downregulation of miR-1 and -206, but not miR-16, in DRG. Moreover, there was no change on any miRNA in the spinal dorsal horn. We extended the nerve injury assay to the neuroma model of neuropathic pain. Interestingly, all miRNA investigated showed a persistent upregulation in DRG following axotomy whereas in the dorsal horn only miR-1 was steadily downregulated. Together, our data strongly reinforces the idea that miRNA expression in the nociceptive system is stimulus-dependent. Recently, the role of Dicer, a cytoplasmic ribonuclease III that generates miRNAs, in controlling inflammatory pain was investigated. By deleting Dicer in DRG neurons expressing the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.8 the authors provided evidence that small double-stranded RNAs, such as miRNAs, are important for regulating nociceptor-associated mRNA transcripts. In addition, CFA-induced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia were abolished in conditional mutant mice [20].

We have also addressed the question whether miRNAs expression would be influenced by acute nociceptive stimulation. Bai and collaborators have shown a significant down-regulation of a number of miRNAs as early as 30 min after CFA injection [18]. We challenge this short-time effect on miRNA expression by injecting capsaicin into the dorsal aspect of the mouse hind paw. Capsaicin immediately depolarizes primary afferent sensory neurons through the transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1, a non-selective cation channel [41]. Interestingly, 10 min after capsaicin injection miR-1 and -16 were up-regulated in DRG. A possible mechanism underlying this phenomenon might involve regulation of immediate-early genes (IEGs), such as c-fos, c-jun and c-myc. These genes show rapid and transient expression in the absence of de novo protein synthesis [42–44]. In particular, c-fos, which is expressed at low levels in the intact brain under basal conditions, is stereotypically induced in response to several extracellular signals, including ions, neurotransmitters, growth factors and drugs [45–47]. It is widely accepted that regulatory IEGs are involved in the stimulus-transcription coupling where c-fos has been considered a generic marker of neuronal depolarization [48–51]. C-Fos protein forms transcriptionally active dimmers with members of the c-jun family, referred to as AP-1 transcription factor. Recent data have associated miRNA activity with Fos mRNA, inhibiting Fos translation [14]. Given the importance of AP-1 as potent transcriptional activator, it is reasonable to speculate that various mechanisms would have evolved to regulate its activity, including miRNA activity. We were also interested in investigating whether miRNA expression would be dependent on stimulus intensity. Behaviorally, capsaicin administration induces a pronounced nocifensive response in a concentration-dependent manner. However, the enhanced miRNA expression in DRG did not show any association between stimulus intensity and expression pattern suggesting a ceiling effect. Conversely, in the spinal dorsal horn 10 μg, but not 2 μg, of capsaicin induced a significant downregulation of miR-206 indicating that miRNAs may also be activated in a stimulus intensity-dependent fashion.

Conclusions

In summary, our data shows that miRNAs are differentially regulated under chronic and acute pain states. We speculate that miRNAs may be involved in the mechanisms underlying different pain conditions by fine-tuning the expression of pro and/or antinociceptive molecules. Whether these miRNAs activity is associated with the mechanisms underlying inflammatory and neuropathic pain cannot be addressed by the present study. The answer to this important question relies primarily on the elucidation of their target mRNAs. However, miRNA may integratedly modulate several genes associated with both the nociceptive and analgesic systems, influencing the dramatic neuronal changes responsible for the development and maintenance of chronic pain conditions. Most important, miRNA expression in the nociceptive system shows not only spatiotemporal specificity but is also stimulus-dependent.

Abbreviations

- A.M.:

-

ante meridiem

- Bdnf:

-

brain derived neurotrophic factor

- Calm2:

-

calmodulin 2

- CFA:

-

complete Freund's adjuvant

- DRG:

-

dorsal root ganglion

- IEG:

-

immediate early gene

- Igf1:

-

insulin-like growth factor 1

- Mapk3:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase 3

- miRNA:

-

miR: microRNA

- mRNA:

-

messenger RNA

- Ngfr:

-

nerve growth factor receptor Oprd1: opioid receptor, delta 1

- Pla2g4a:

-

phospholipase A2, group IVA (cytosolic, calcium-dependent)

- P.M.:

-

post meridiem

- RT-PCR:

-

real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- RQ:

-

relative quantification

- TG:

-

trigeminal ganglion

- Trpc3:

-

transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily C, member 3

- 3' UTR:

-

three prime untranslated region

References

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116: 281–297. 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5

He L, Hannon GJ: MicroRNAs: small RNAs with a big role in gene regulation. Nat Rev Genet 2004, 5: 522–531. 10.1038/nrg1379

Kosik KS, Krichevsky AM: The Elegance of the MicroRNAs: A Neuronal Perspective. Neuron 2005, 47: 779–782. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.019

Mattick JS, Makunin IV: Small regulatory RNAs in mammals. Hum Mol Genet 2005,14(1):R121–132. 10.1093/hmg/ddi101

Mehler MF, Mattick JS: Non-coding RNAs in the nervous system. J Physiol 2006, 575: 333–341. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113191

Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V: The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75: 843–854. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y

Ambros V: microRNAs: tiny regulators with great potential. Cell 2001, 107: 823–826. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00616-X

Du T, Zamore PD: microPrimer: the biogenesis and function of microRNA. Development 2005, 132: 4645–4652. 10.1242/dev.02070

Kim VN: MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2005, 6: 376–385. 10.1038/nrm1644

Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T: Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol 2002, 12: 735–739. 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00809-6

Schratt GM, Tuebing F, Nigh EA, Kane CG, Sabatini ME, Kiebler M, Greenberg ME: A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature 2006, 439: 283–289. 10.1038/nature04367

Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP: MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 2004, 303: 83–86. 10.1126/science.1091903

Kim HK, Lee YS, Sivaprasad U, Malhotra A, Dutta A: Muscle-specific microRNA miR-206 promotes muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol 2006, 174: 677–687. 10.1083/jcb.200603008

Lee HJ, Palkovits M, Young WS: miR-7b, a microRNA up-regulated in the hypothalamus after chronic hyperosmolar stimulation, inhibits Fos translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006, 103: 15669–15674. 10.1073/pnas.0605781103

Li Y, Wang F, Lee JA, Gao FB: MicroRNA-9a ensures the precise specification of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Genes Dev 2006, 20: 2793–2805. 10.1101/gad.1466306

Yang B, Lin H, Xiao J, Lu Y, Luo X, Li B, Zhang Y, Xu C, Bai Y, Wang H, Chen G, Wang Z: The muscle-specific microRNA miR-1 regulates cardiac arrhythmogenic potential by targeting GJA1 and KCNJ2. Nat Med 2007, 13: 486–491. 10.1038/nm1569

Lee YS, Dutta A: MicroRNAs: small but potent oncogenes or tumor suppressors. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2006, 7: 560–564.

Bai G, Ambalavanar R, Wei D, Dessem D: Downregulation of selective microRNAs in trigeminal ganglion neurons following inflammatory muscle pain. Mol Pain 2007, 3: 15–18. 10.1186/1744-8069-3-15

Aldrich BT, Frakes EP, Kasuya J, Hammond DL, Kitamoto T: Changes in expression of sensory organ-specific microRNAs in rat dorsal root ganglia in association with mechanical hypersensitivity induced by spinal nerve ligation. Neuroscience 2009, 164: 711–23. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.033

Zhao J, Lee MC, Momin A, Cendan CM, Shepherd ST, Baker MD, Asante C, Bee L, Bethry A, Perkins JR, Nassar MA, Abrahamsen B, Dickenson A, Cobb BS, Merkenschlager M, Wood JN: Small RNAs control sodium channel expression, nociceptor excitability, and pain thresholds. J Neurosci 2010, 30: 10860–10871. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1980-10.2010

Hokfelt T, Zhang X, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z: Messenger plasticity in primary sensory neurons following axotomy and its functional implications. Trends Neurosci 1994, 17: 22–30. 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90031-0

Honore P, Rogers SD, Schwei MJ, Salak-Johnson JL, Luger NM, Sabino MC, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW: Murine models of inflammatory, neuropathic and cancer pain each generates a unique set of neurochemical changes in the spinal cord and sensory neurons. Neuroscience 2000, 98: 585–598. 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00110-X

Honore P, Schwei J, Rogers SD, Salak-Johnson JL, Finke MP, Ramnaraine ML, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW: Cellular and neurochemical remodeling of the spinal cord in bone cancer pain. Prog Brain Res 2000, 129: 389–397. full_text

Kim SK, Nam JW, Rhee JK, Lee WJ, Zhang BT: miTarget: microRNA target gene prediction using a support vector machine. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7: 411. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-411

Rodriguez Parkitna J, Korostynski M, Kaminska-Chowaniec D, Obara I, Mika J, Przewlocka B, Przewlocki R: Comparison of gene expression profiles in neuropathic and inflammatory pain. J Physiol Pharmacol 2006, 57: 401–414.

Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Meyer J, Borkhardt A, Tuschl T: New microRNAs from mouse and human. RNA 2003, 9: 175–179. 10.1261/rna.2146903

Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N: Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet 2005, 37: 495–500. 10.1038/ng1536

Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB: Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell 2003, 115: 787–798. 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01018-3

Zimmermann M: Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 1983, 16: 109–110. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90201-4

Seltzer Z, Dubner R, Shir Y: A novel behavioral model of neuropathic pain disorders produced in rats by partial sciatic nerve injury. Pain 1990, 43: 205–218. 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91074-S

Dixon WJ: Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1980, 20: 441–462. 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301

Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL: Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 1994, 53: 55–63. 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25: 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Alvares D, Fitzgerald M: Building blocks of pain: the regulation of key molecules in spinal sensory neurones during development and following peripheral axotomy. Pain 1999,6(Suppl):S71–85. 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00140-2

Woolf CJ: Phenotypic modification of primary sensory neurons: the role of nerve growth factor in the production of persistent pain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1996, 351: 441–448. 10.1098/rstb.1996.0040

Mannion RJ, Costigan M, Decosterd I, Amaya F, Ma QP, Holstege JC, Ji RR, Acheson A, Lindsay RM, Wilkinson GA, Woolf CJ: Neurotrophins: peripherally and centrally acting modulators of tactile stimulus-induced inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96: 9385–9390. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9385

Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R: MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol 2005, 7: 719–723. 10.1038/ncb1274

Fabian MR, Sonenberg N, Filipowicz W: Regulation of mRNA translation and stability by microRNAs. Annu Rev Biochem 2010, 79: 351–379. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060308-103103

Herranz H, Cohen SM: MicroRNAs and gene regulatory networks: managing the impact of noise in biological systems. Genes Dev 2010, 24: 1339–1344. 10.1101/gad.1937010

Newman MA, Hammond SM: Emerging paradigms of regulated microRNA processing. Genes Dev 2010, 24: 1086–1092. 10.1101/gad.1919710

Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D: The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997, 389: 816–824. 10.1038/39807

Barth AL: Visualizing circuits and systems using transgenic reporters of neural activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007, 17: 567–571. 10.1016/j.conb.2007.10.003

Kovacs KJ: Measurement of immediate-early gene activation-c-fos and beyond. J Neuroendocrinol 2008, 20: 665–672. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01734.x

Sng JC, Taniura H, Yoneda Y: A tale of early response genes. Biol Pharm Bull 2004, 27: 606–612. 10.1248/bpb.27.606

Coggeshall RE: Fos, nociception and the dorsal horn. Prog Neurobiol 2005, 77: 299–352.

Lima D, Almeida A: The medullary dorsal reticular nucleus as a pronociceptive centre of the pain control system. Prog Neurobiol 2002, 66: 81–108. 10.1016/S0301-0082(01)00025-9

Zhao ZQ: Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008, 85: 355–375. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.05.004

Herdegen T, Zimmermann M: Immediate early genes (IEGs) encoding for inducible transcription factors (ITFs) and neuropeptides in the nervous system: functional network for long-term plasticity and pain. Prog Brain Res 1995, 104: 299–321. full_text

Loebrich S, Nedivi E: The function of activity-regulated genes in the nervous system. Physiol Rev 2009, 89: 1079–103. 10.1152/physrev.00013.2009

Harris JA: Using c-fos as a neural marker of pain. Brain Res Bull 1998, 45: 1–8. 10.1016/S0361-9230(97)00277-3

Zimmermann M: Immediate-early genes in the nervous system-are they involved in mechanisms of chronic pain? Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter 1992, 4: 47–51.

Kerr BJ, Bradbury EJ, Bennett DL, Trivedi PM, Dassan P, French J, Shelton DB, McMahon SB, Thompson SW: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates nociceptive sensory inputs and NMDA-evoked responses in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 1999, 19: 5138–5148.

Merighi A, Salio C, Ghirri A, Lossi L, Ferrini F, Betelli C, Bardoni R: BDNF as a pain modulator. Prog Neurobiol 2008, 85: 297–317. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.04.004

Thompson SW, Bennett DL, Kerr BJ, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is an endogenous modulator of nociceptive responses in the spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96: 7714–7718. 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7714

Galan A, Lopez-Garcia JA, Cervero F, Laird JM: Activation of spinal extracellular signaling-regulated kinase-1 and -2 by intraplantar carrageenan in rodents. Neurosci Lett 2002, 322: 37–40. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00078-2

Wei F, Qiu CS, Kim SJ, Muglia L, Maas JW, Pineda VV, Xu HM, Chen ZF, Storm DR, Muglia LJ, Zhuo M: Genetic elimination of behavioral sensitization in mice lacking calmodulin-stimulated adenylyl cyclases. Neuron 2002, 36: 713–726. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01019-X

Zeitz KP, Giese KP, Silva AJ, Basbaum AI: The contribution of autophosphorylated alpha-calcium-calmodulin kinase II to injury-induced persistent pain. Neuroscience 2004, 128: 889–898. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.029

Davar G, Shalish C, Blumenfeld A, Breakfield XO: Exclusion of p75NGFR and other candidate genes in a family with hereditary sensory neuropathy type II. Pain 1996, 67: 135–139. 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03113-2

Fukui Y, Ohtori S, Yamashita M, Yamauchi K, Inoue G, Suzuki M, Orita S, Eguchi Y, Ochiai N, Kishida S, Takaso M, Wakai K, Hayashi Y, Aoki Y, Takahashi K: Low affinity NGF receptor (p75 neurotrophin receptor) inhibitory antibody reduces pain behavior and CGRP expression in DRG in the mouse sciatic nerve crush model. J Orthop Res 2009, 28: 279–283.

Watanabe T, Ito T, Inoue G, Ohtori S, Kitajo K, Doya H, Takahashi K, Yamashita T: The p75 receptor is associated with inflammatory thermal hypersensitivity. J Neurosci Res 2008, 86: 3566–3574. 10.1002/jnr.21808

Hasegawa S, Kohro Y, Shiratori M, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Tsuda M, Inoue K: Role of PAF receptor in proinflammatory cytokine expression in the dorsal root ganglion and tactile allodynia in a rodent model of neuropathic pain. PLoS One 2010, 5: e10467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010467

Inoue M, Ma L, Aoki J, Ueda H: Simultaneous stimulation of spinal NK1 and NMDA receptors produces LPC which undergoes ATX-mediated conversion to LPA, an initiator of neuropathic pain. J Neurochem 2008, 107: 1556–1565. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05725.x

Yeo JF, Ong WY, Ling SF, Farooqui AA: Intracerebroventricular injection of phospholipases A2 inhibitors modulates allodynia after facial carrageenan injection in mice. Pain 2004, 112: 148–155. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.009

Contreras PC, Vaught JL, Gruner JA, Brosnan C, Steffler C, Arezzo JC, Lewis ME, Kessler JA, Apfel SC: Insulin-like growth factor-I prevents development of a vincristine neuropathy in mice. Brain Res 1997, 774: 20–26. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)81682-4

de Pablo F, Banner LR, Patterson PH: IGF-I expression is decreased in LIF-deficient mice after peripheral nerve injury. Neuroreport 2000, 11: 1365–1368. 10.1097/00001756-200004270-00043

Staaf S, Oerther S, Lucas G, Mattsson JP, Ernfors P: Differential regulation of TRP channels in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Pain 2009, 144: 187–199. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.013

Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Karchewski LA, Hever X, Matifas A, Kieffer BL: Inflammatory pain is enhanced in delta opioid receptor-knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci 2008, 27: 2558–2567. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06223.x

Nadal X, Banos JE, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R: Neuropathic pain is enhanced in delta-opioid receptor knockout mice. Eur J Neurosci 2006, 23: 830–834. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04569.x

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Profs. Margaret de Castro, and Angela Kaysel Cruz for providing equipment facilities. This project was supported by the São Paulo State Research Foundation-FAPESP (grant no. 07/00002-2), and the University of São Paulo research funds. R.K., F.C., and M.I.R. were supported by FAPESP fellowships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RK, tissue extraction, RNA purifying, real time PCR assays, data analysis. FC, conducted behavioral tests, tissue extraction, real time PCR assays. MIR, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. TAS, RNA purification, reverse transcriptase and real time PCR assays. SZ, tissue extraction, RNA purifying, reverse transcriptase and real time PCR assays. FLL, study design, and data analysis. GL, study design, coordinated the project, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kusuda, R., Cadetti, F., Ravanelli, M.I. et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in mouse pain models. Mol Pain 7, 17 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-7-17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-7-17