Abstract

Background

Air pollution, mainly from combustion, is one of the leading global health risk factors. A susceptible group is the more than 200 million people worldwide suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). There are few data on lung deposition of airborne particles in patients with COPD and none for combustion particles.

Objectives

To determine respiratory tract deposition of diesel combustion particles in patients with COPD during spontaneous breathing.

Methods

Ten COPD patients and seven healthy subjects inhaled diesel exhaust particles generated during idling and transient driving in an exposure chamber. The respiratory tract deposition of the particles was measured in the size range 10–500 nm during spontaneous breathing.

Results

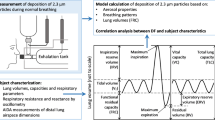

The deposited dose rate increased with increasing severity of the disease. However, the deposition probability of the ultrafine combustion particles (< 100 nm) was decreased in COPD patients. The deposition probability was associated with both breathing parameters and lung function, but could be predicted only based on lung function.

Conclusions

The higher deposited dose rate of inhaled air pollution particles in COPD patients may be one of the factors contributing to their increased vulnerability. The strong correlations between lung function and particle deposition, especially in the size range of 20–30 nm, suggest that altered particle deposition could be used as an indicator respiratory disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

More than 200 million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and of these 3 million die each year [1, 2]. Today the disease is the fourth most common cause of death globally and it is predicted to become the third within the next decade. One crucial consequence of COPD is an increased susceptibility to air pollution, which could be partly related to a deviation in the uptake of airborne particles during breathing. Air pollution in urban and indoor environments is one of the leading global adverse health factors [3]. Most of these air pollution particles originate from combustion.

The two most important individual characteristics determining the probability of an inhaled particle to deposit in the lungs are breathing pattern and lung morphology. Both these are substantially altered in patients with COPD. Nevertheless, few studies are available on respiratory tract particle deposition in COPD patients in the size range below 1 μm, where much of the ambient airborne particle pollution is found [4–6]. Of these studies, only one investigate a size range which partly covers typical ambient aerosol (20–240 nm, [4]), while the other two examines particles of a single size (33 nm and 100 nm, respectively, [5, 6]). Two of these three studies employ controlled pre-determined breathing patterns and are therefore difficult to use for estimation of real-world exposure. Since just one of the studies ([5], using 33 nm particles) varied flow rates while the others kept them constant, relationships between breathing pattern and deposition are not easy to establish.

Thus, several important aspects of the deposition of particles in COPD patients require further examination. The probability of an inhaled particle to deposit in the lungs may vary from more than 80% for particles smaller than 30 nm in diameter to below 20% for particles around 500 nm. For particle sizes other than 33 nm, deposition in COPD during spontaneous breathing is still unclear. Measurements on lung deposition of particles likely to be found in the environment, such as those from combustion sources, have not been performed in COPD.

The objective of this work was to experimentally investigate the respiratory tract deposition in COPD patients for two types of diesel exhaust particles (DEPs) in the range 10 to 500 nm during spontaneous breathing and to seek relationships between deposition, breathing parameters and lung function (static and dynamic spirometry, including diffusion capacity). DEPs were used because they are ubiquitous in the urban atmosphere, have a well-characterized toxicology and are described to cause adverse respiratory and cardiovascular responses [7–10]. It has also been shown that DEPs in the range 10–300 nm have a similar deposition probability for healthy subjects as spherical hydrophobic particles of similar mobility diameter [11]. Epidemiological studies have linked exposure to DEPs with increased COPD mortality [12].

Results

Diesel exhaust particles

The respiratory tract deposition of DEPs from both idling engine and simulated transient driving was investigated (Figure 1). Idling engine emitted a bimodal aerosol consisting of a nucleation mode with geometric mean diameter (GMD) at 16 nm (geometric standard deviation, σg, 1.52) and an accumulation mode with a GMD of 75 nm (σg 1.98). The particles from transient driving were unimodal with a GMD of 88 nm (σg 1.97). Number concentrations were 82000 ± 22000 cm-3 for idling and 222000 ± 13000 cm-3 for transient driving. Further information about the aerosols is provided in the online Additional file 1 and in a previous publication [11].

Subject characteristics

Subject demographics, breathing parameters and pulmonary function data of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. The subjects with COPD had a significantly lower FEV1/FVC, FEV1, DLCO/VA and PEF than the healthy group. Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLCO) was not obtained from two of the healthy subjects. Some of the healthy subjects breathed with a lower frequency, f, and a higher tidal volume, VT, than expected at rest [13]. The spontaneous breathing of the COPD patients was in reasonable agreement with estimated normal values [14]. One healthy subject was excluded because breathing was considered forced (f = 4.5 breaths/min, VT = 2.7 L).

Deposition fraction, DF

The deposition fraction (DF) was calculated from the difference between inhaled and exhaled particle concentrations (see Method section, online Additional file 1 and previous publications [15] for details). Each subject had a similar DF for both types of DEPs, which is expected considering the physical and chemical characteristics of the particles [11]. The similar DFs for both exposures also indicate a repeatable behavior of the subjects combined with stability of the experimental set-up. For this reason, the DFs were averaged for the two types of DEPs in the following analysis, if not stated otherwise.

For most the ultrafine particles size range (< 100 nm), the DF of inhaled DEPs was significantly lower in COPD patients compared to the healthy group: below 80 nm with p < 0.05 and below 50 nm with p < 0.001 (Figure 2). For particles larger than 100 nm, the DF was equal or higher in the COPD patients, but differences were not significant.

Measured size-dependent deposition fractions of diesel exhaust particles (DEPs). Data are shown as group means of both types of DEPs for healthy subjects and COPD patients. For comparison, the deposition fractions are also shown for spherical hydrophobic oil particles for healthy subjects in a previous study (Löndahl et al. 2007). Bars indicate standard deviation between subjects.

The DF may be calculated not only as the size dependent value, but also as a total DF meaning the fraction of the complete aerosol that is deposited. Unlike the size dependent DF, the total DF is partly determined by the particle size distribution. Table 2 shows values of the total DF by number, surface area and mass of the two types of DEPs. The only significant difference is the total DF of the DEPs by number (p < 0.05). The surface area and mass of the DEPs are dominated by the larger particles (100–500 nm) and for these the COPD patients and the healthy group had a more similar DF.

Breathing pattern, lung function and DF

Although each subject had a similar DF for both types of DEPs, there was considerable variability in DF between the subjects: 0.6-0.9 for 20 nm particles and 0.1-0.2 for 500 nm particles. The variability was related to differences in both breathing pattern and lung function (Table 3 left column). Correlations were typically stronger for smaller sized particles. No significant correlations were found between DF and breathing pattern or lung function for particles larger than 100 nm. The associations shown in Table 3 for 20–30 nm particles were similar for particles in the range 30–100 nm, but typically with a lower level of significance. Notably DF of 20–30 nm particles was strongly positively correlated with lung function deviations characteristic for COPD: FEV1 (r = 0.59, p = 0.01), percentage predicted FEV1 (r = 0.59, p = 0.01), FEV1/FVC (r = 0.79, p = 0.00002), percentage predicted FEV1/FVC (r = 0.79, p = 0.0001) and diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide, DLCO/VA (r = 0.61, p = 0.02). The correlation between DF and FEV1/FVC is illustrated in Figure 3.

COPD patients with emphysema typically have an increased residual volume (RV) as was the case for the participants in this study. There was a clear negative correlation between RV and DF of 20–30 nm particles (r = −0.57, p = 0.02). This indicates that emphysema decreases deposition probability of inhaled ultrafine aerosol particles.

Breathing frequency and minute ventilation, but not tidal volume (VT), correlated significantly with DF in the ultrafine particle size interval (Table 3). Increases in breathing frequency and minute ventilation were associated with decrease in DF of ultrafine particles (p < 0.005). No associations between DF and breathing pattern were found for particles larger than 100 nm.

Multivariate linear regression analysis suggested that DF of the ultrafine particles (20–100 nm) for the COPD patients could be predicted based on particle diameter (dp, [nm]) and FEV1/FVC:

The Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for this equation is 0.94.

Deposited dose rate

The deposited dose rate here refers to the deposited amount of particles by number, surface area or mass per unit time. The deposited dose rates of DEPs from idle engine and transient driving are provided in Table 4 and illustrated for particle mass in Figure 4. The deposited dose rates are derived from the measured DFs and particle size distribution. For determination of deposited dose rates by surface area and mass also density of the DEPs and TEM image-analysis were used as described in detail by Rissler et al. [11]. Unlike DF, the deposited dose rate differed substantially between the two types of DEPs since it is partly determined by particle size distribution.

The mean deposited dose rate tended to be higher for patients with COPD compared to the healthy group, although the difference was only significant for DEPs generated during idling (Figure 4). The reason for the elevated deposited dose rate is that the COPD patients breathed with higher minute ventilation (MV, Table 1) and therefore inhaled more particles. A strong positive correlation was found between MV and deposited mass-dose (r = 0.77, p = 0.0003). However, as previously described, DF was lower in the COPD patients for most particle sizes and this partly counterbalanced the particle uptake.

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, the deposited mass of DEPs per hour (deposited dose rate by mass) increased with disease severity (i.e. with decrease in FEV1, FEV1/FVC and DLCO/VA). Most significant was the association between deposited dose rate by mass and DLCO/VA (p = 0.0004, Figure 5). The inter-subject variability in deposited dose rate was larger than the variability in DF because of substantial variation in minute ventilation. Based on the experimental results, the individual deposited dose rates ranged from 0.09 to 0.22 μg/hour with the particle concentration normalized to 1 μg/m3 of DEPs.

Discussion

The respiratory tract deposition of two types of DEPs was determined in the particle size range 10–500 nm for COPD patients and healthy controls. In contrast to most previous studies, in which subjects breathed according to a pre-determined pattern, spontaneous breathing was used here to resemble real-world exposure. It was found that the respiratory tract deposition of DEPs was closely associated with both breathing parameters and lung function. The deposited dose rate increased with COPD severity, mainly due to increased minute ventilation. The two types of particles studied are representative for DEPs in general as reported in several previous studies [11].

Deposition fraction, DF

The size-resolved DF of DEPs for the healthy group of subjects (Figure 1) was in agreement with previous measurements for hydrophobic spherical particles [16]. The DF has previously been determined for particles from diesel exhaust, traffic and biomass combustion in healthy subjects [17–19]. It was shown that the DF of combustion particles could be predicted with high accuracy (within 10%) by using the DFs for hydrophobic particles, but with an adjustment for particle size changes due to absorption of water vapor in the lungs [17, 18]. The relative humidity in the lungs is high, 99.5%, and therefore inhaled non-hydrophobic particles grow by uptake of water. It is the size of the particles inside the lungs that determines deposition rather than the measured dry size. The DEPs in this study were hydrophobic due to low sulfur content in the fuel [11]. When the deposited dose rate is calculated, density and agglomeration also must be considered [18].

Both images from electron microscopy and density measurements showed that the DEPs were highly agglomerated. Experiments with a cast of human lung airways have suggested that agglomerated particles may have a somewhat higher DF at lung bifurcations than spherical particles with equal mobility diameters [20]. However, the difference in DF between DEPs and hydrophobic spheres of equal mobility size was insignificant for human subjects (Figure 2, see also [11]). The close similarity in DF between DEPs and spherical oil particles is in general agreement with theory. Particles below 300 nm in diameter deposit primarily through Brownian diffusion – the movement caused by random collisions with gas molecules. For hydrophobic particles in this size range, deviations in density and shape have a minor impact on diffusion speed and, consequently, do not affect the DF, provided that particle size is given in mobility diameter, as in this research. The mobility diameter is the commonly used diameter for particles < 0.5 μm. For spherical particles, it is identical to the geometric diameter (i.e. the diameter measured by a ruler on a picture).

Breathing pattern, lung function and DF

The associations between subject characteristics and DF were in general most significant for particles in the range 20–30 nm, although similar trends were clear over the complete ultrafine size range. The lower DF for ultrafine particles in COPD could partly be explained by variations in breathing pattern. As expected [14], the COPD patients had a higher breathing frequency and minute ventilation than the healthy group (Table 1). This reduces residence time in the lungs, which decreases the DF as less time for diffusion is available.

It is likely that not only alterations in breathing pattern but also variations in airway morphology may reduce the DF in COPD. According to the majority of the lung deposition models, particles in the range 20–70 nm deposit by diffusion, primarily in the alveolar region. In patients with emphysema, the air spaces are enlarged due to destruction of the alveolar walls [21]. As a consequence, the particles have to travel a longer distance before deposition. Hence, the deposition probability decreases. Comparisons with the common ICRP model (International Commission on Radiological Protection) are further elaborated in the online Additional file 1.

Three previous studies have investigated respiratory tract deposition of aerosol particles smaller than 0.5 μm in COPD patients [4–6]. Brown et al. [5] studied the deposition of particles with a count mean diameter of 33 nm (σg 1.7) during spontaneous breathing in 9 healthy subjects and 10 patients with COPD, whereof 7 were bronchitic and 3 emphysematic (defined as those with percentage predicted DLCO/VA < 60%). The COPD patients with emphysema had a significantly lower DF than the healthy group, whereas those classified as bronchitic had a higher. In agreement with the emphysematic group we found a decrease in DF of ultrafine particles.

Comparison of the DF between this study and the two studies in which pre-determined breathing patterns were used is less straightforward. Anderson et al. [4] determined the deposition of hydrophobic 20–240 nm particles in 10 healthy subjects and 8 patients, whereof 5 and 3 had obstructive and restrictive lung disease, respectively. Compared to the healthy group, they found that DF was increased in patients with obstructive lung disease but remained unchanged in those with restrictive lung disease. However, the subjects with obstructive lung disease had difficulties following the pre-determined breathing pattern and this was suggested as a possible explanation to the increased DF. Möller et al. [6] also found a small increase in DF during deep inhalation, but since an 8-second breath hold was carried out at the end of inhalation, results are not comparable.

Several correlations were found between DF and lung function in the present study (Table 3). Brown et al. did not find any associations between DF and lung function across all subjects, but observed relationships between DF and percentage predicted FEV1 and percentage predicted DLCO/VA in the group of COPD patients alone and in the combined group of bronchitic and healthy subjects. The correlations between DF and lung function in the COPD patients were in close agreement with those obtained here. Möller et al. did not report on relationships between DF and lung function and no associations were demonstrated in the study by Anderson et al.

The strong correlations observed between lung function and the DF of particles in the range 20–30 nm suggest that determination of the DF for particles of this size may be a suitable tool for evaluation of respiratory disease. It is argued above that not only breathing pattern, but also airway morphology is a reason for the abnormal deposition. Numerous studies investigate the use of deposition of aerosol particles as a tool to diagnose lung disease [22–24]. However, these studies focus on particles larger than 400 nm.

Deposited dose rate

The COPD patients were found to have an increased deposited dose rate of DEPs generated during idling along with a tendency towards a significantly increased deposited dose rate for particles emitted during transient driving (Figure 4). The increased deposited dose rate is in agreement with the results of Brown et al [5]. The reason for the increase in deposited dose rate is the higher minute ventilation in COPD. The subjects with the highest deposited dose rates received about 2.5 times more particles than those with the lowest (Figure 5).

A higher deposited dose rate may be one possible explanation for the increased vulnerability to air pollution exposure found in many toxicological and epidemiological studies in patients with COPD. The deposited dose rate, unlike the size dependent DF, is influenced by size distribution, which varies between different diesel engines. At similar mass concentrations, the number of particles in the air will be larger if the size distribution is dominated by many small particles rather than a few large ones. Therefore, the deposited dose rate of DEPs may vary. When calculating the deposited dose rate for aggregated particles, such as DEPs, the particles effective density must be considered (see online Additional file 1).

Conclusion

In summary, the COPD patients had an increased deposited dose rate of DEPs, primarily because of heightened minute ventilation (MV). Increased deposited dose rates are believed to enhance the harmful effects of inhaled particles. A strong association was found between severity of COPD and deposited dose rate of inhaled DEPs since low DLCO/VA and FEV1/FVC resulted in a high respiratory tract deposition. Strong associations were also found between the deposition fraction and lung function, in particular for 20–30 nm particles. The results suggest that measurements of the respiratory tract deposition of 20–30 nm particles may be valuable in the evaluation of respiratory disease.

Since the deposition of DEPs for healthy subjects was similar to the deposition of spherical hydrophobic particles of similar mobility size (as is also expected from theory), the presented results could be assumed to apply not only to DEPs but also to other spherical or agglomerated hydrophobic nanoparticles in at least the range 10–300 nm.

Methods

Subjects

Two groups of volunteers were recruited: I) 8 healthy non-smokers with normal lung function (3 men, 5 women, age 23–43 yrs, median 26 yrs), and II) 10 patients with COPD (7 men, 3 women, age 59–78 yrs, median 65 yrs). The COPD patients were ex-smokers with a smoking history of at least 10 pack years and disease severity ranging from stage 2–3, according to the 2008 GOLD guidelines [25]. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects.

Aerosol generation

Subjects were exposed to diesel exhaust particles (DEPs) generated by a standard truck engine (Volvo TD40 GJE, 4.0 L, four cylinders, 1996) with no exhaust after-treatment. The engine was operated in a motor test bench in order to simulate two typical engine loads: idling and transient load consistent with the urban driving part of the standardized European Transient Cycle (ETC.) protocol. The concentrated DEPs from the engine exhaust were diluted in a procedure optimized to mimic ambient conditions and thereafter introduced into a human exposure chamber (described in detail elsewhere [7, 8]). DEPs from idling and transient load were studied separately.

The daily average mass concentration of DEPs in the chamber was 59 ± 5 μg/m3 (as PM1) during idling and 300 ± 2 μg/m3 during transient load, as measured by a tapered element oscillating microbalance (TEOM). Further information regarding the physical and chemical characterization of the DEPs is provided in the online Additional file 1 and a previous publication [11].

Respiratory tract deposition

The subjects completed two exposure sessions, one for each type of DEPs. The sessions were randomized on different days and the aerosol type was unknown to the subjects. Each session began with a 3-minute test period for subjects to get accustomed to the equipment, followed by an exposure of 2x15 minutes.

The respiratory tract deposition of the DEPs was determined by a novel method (RESPI) [15]. In summary, subjects wearing a nose clip breathed spontaneously through a mouthpiece while sitting in a relaxed position. The concentration of DEPs in the range 10–500 nm was measured in separate containers for inhaled and exhaled air with a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS). Thereafter the deposition fraction (DF) was determined by comparing the size-resolved number of DEPs in the two containers. Corrections were made for particle losses in the instrument and for mouthpiece dead space [15, 26]. The DEPs were dried to below 20% relative humidity before measurement. Further information is provided in the online Additional file 1 and in a separate publication [11].

Calculations

The deposited dose per hour of exposure (the deposited dose rate) was derived as the probability of the DEPs to deposit (DF) multiplied by the inhaled amount of particles by mass or number during one hour. Calculation of the surface area of the deposited particles involves uncertain assumptions on particle structure and is discussed in the online Additional file 1. To facilitate comparisons between the subjects, the concentration of the inhaled DEPs was normalized to 1 μg/m3 for the deposited dose rate calculation. The size-dependent mass concentration was determined by combining measurements of particle size distribution (SMPS) and effective density (APM, Aerosol Particle Mass analyzer).

Differences between data means were evaluated with the t-test using SPSS (SPSS Inc., IBM Corporation, version 19). Dependence between variables was investigated with Pearson’s correlation and multivariate linear modeling across all subjects. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- DEPs:

-

Diesel Exhaust Particles

- DF:

-

Deposition Fraction

- DF20-30:

-

Deposition Fraction of 20–30 nm particles

- DLCO:

-

Diffusion Capacity of Carbon monoxide

- DLCO/VA:

-

Diffusion Capacity of Carbon monoxide normalized to lung volume

- f:

-

breathing frequency

- FEV1:

-

Forced Expiratory Volume in one second

- FEV:

-

Forced Vital Capacity

- MEF25/50:

-

Maximum Expiratory Flow rate at 25% and 50% of VC respectively

- MV:

-

Minute Ventilation

- PEF:

-

Peak Expiratory Flow

- PM:

-

Particulate Matter

- TLC:

-

Total Lung Capacity

- VC:

-

Vital Capacity

- VT:

-

Tidal Volume.

References

Bousquet J, Khaltaev N (Eds): Global surveillance, prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases: A comprehensive approach. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, Geneva, Switzerland; 2007. ISBN 978 92 4 15634 8

World Health Organization: The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 2008.

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL: Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006, 367: 1747–1757. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9

Anderson PJ, Wilson JD, Hiller FC: Respiratory-Tract Deposition of Ultrafine Particles in Subjects with Obstructive Or Restrictive Lung-Disease. Chest 1990, 97: 1115–1120. 10.1378/chest.97.5.1115

Brown JS, Zeman KL, Bennett WD: Ultrafine particle deposition and clearance in the healthy and obstructed lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166: 1240–1247. 10.1164/rccm.200205-399OC

Möller W, Felten K, Sommerer K, Scheuch G, Meyer G, Meyer P, Haussinger K, Kreyling WG: Deposition, retention, and translocation of ultrafine particles from the central airways and lung periphery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008, 177: 426–432.

Barath S, Mills NL, Lundback M, Tornqvist H, Lucking AJ, Langrish JP, Soderberg S, Boman C, Westerholm R, Londahl J, et al.: Impaired vascular function after exposure to diesel exhaust generated at urban transient running conditions. Part Fibre Toxicol 2010, 7: 19. 10.1186/1743-8977-7-19

Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Robinson SD, Gonzalez M, Darnley K, MacNee W, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, et al.: Diesel exhaust inhalation causes vascular dysfunction and impaired endogenous fibrinolysis. Circulation 2005, 112: 3930–3936. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588962

Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Gonzalez MC, Vink E, Robinson SD, Soderberg S, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A, et al.: Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2007, 357: 1075–1082. 10.1056/NEJMoa066314

Salvi S, Blomberg A, Rudell B, Kelly F, Sandstrom T, Holgate ST, Frew A: Acute inflammatory responses in the airways and peripheral blood after short-term exposure to diesel exhaust in healthy human volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999, 159: 702–709.

Rissler J, Swietlicki E, Bengtsson A, Boman C, Pagels J, Sandström T, Blomberg A, Löndahl J: Experimental determination of deposition of diesel exhaust particles in the human respiratory tract. J Aerosol Sci 2012, 48: 18–33.

Hart JE, Laden F, Eisen EA, Smith TJ, Garshick E: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality in railroad workers. Occup Environ Med 2009, 66: 221–226.

Tobin MJ, Chadha TS, Jenouri G, Birch SJ, Gazeroglu HB, Sackner MA: Breathing Patterns .1. Normal Subjects. Chest 1983, 84: 202–205. 10.1378/chest.84.2.202

Tobin MJ, Chadha TS, Jenouri G, Birch SJ, Gazeroglu HB, Sackner MA: Breathing Patterns .2. Diseased Subjects. Chest 1983, 84: 286–294. 10.1378/chest.84.3.286

Löndahl J, Pagels J, Swietlicki E, Zhou JC, Ketzel M, Massling A, Bohgard M: A set-up for field studies of respiratory tract deposition of fine and ultrafine particles in humans. J Aerosol Sci 2006, 37: 1152–1163. 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2005.11.004

Löndahl J, Massling A, Pagels J, Swietlicki E, Vaclavik E, Loft S: Size-resolved respiratory-tract deposition of fine and ultrafine hydrophobic and hygroscopic aerosol particles during rest and exercise. Inhal Toxicol 2007, 19: 109–116. 10.1080/08958370601051677

Löndahl J, Pagels J, Boman C, Swietlicki E, Massling A, Rissler J, Blomberg A, Bohgard M, Sandstrom T: Deposition of biomass combustion aerosol particles in the human respiratory tract. Inhal Toxicol 2008, 20: 923–933. 10.1080/08958370802087124

Löndahl J, Massling A, Swietlicki E, Brauner EV, Ketzel M, Pagels J, Loft S: Experimentally Determined Human Respiratory Tract Deposition of Airborne Particles at a Busy Street. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43: 4659–4664. 10.1021/es803029b

Morawska L, Hofmann W, Hitchins-Loveday J, Swanson C, Mengersen K: Experimental study of the deposition of combustion aerosols in the human respiratory tract. J Aerosol Sci 2005, 36: 939–957. 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2005.03.015

Scheckman JH, Mcmurry PH: Deposition of silica agglomerates in cast of human lung airways: Enhancement relative to spheres of equal mobility and aerodynamic diameter. J Aerosol Sci 2011, 42: 508–516. 10.1016/j.jaerosci.2011.05.003

O'Donnell MD, O'Connor CM, FitzGerald MX, Lungarella G, Cavarra E, Martorana PA: Ultrastructure of lung elastin and collagen in mouse models of spontaneous emphysema. Matrix Biol 1999, 18: 357–360. 10.1016/S0945-053X(99)00031-1

Beinert T, Brand P, Behr J, Vogelmeier C, Heyder J: Peripheral Airspace Dimensions in Patients with Copd. Chest 1995, 108: 998–1003. 10.1378/chest.108.4.998

Bennett WD, Smaldone GC: Use of Aerosols to Estimate Mean Air-Space Size in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary-Disease. J Appl Physiol 1988, 64: 1554–1560.

Kim CS, Lewars GA, Sackner MA: Measurement of Total Lung Aerosol Deposition As An Index of Lung Abnormality. J Appl Physiol 1988, 64: 1527–1536.

GOLD executive committee: Pocket guide to COPD diagnosis,management and prevention. A guide for health care professionals. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD); 2011. http://www.goldcopd.org/

Gebhart J, Schiller CF, Egan MJ, Nixon W: On the Relationship Between Experimental-Data for Total Deposition and Model-Calculations .1. Effect of Instrumental Dead Space. J Aerosol Sci 1989, 20: 141–147. 10.1016/0021-8502(89)90039-6

Acknowledgements

The following organizations are gratefully acknowledged for financial support: The Swedish Emission Research Programme (EMFO, contract AL 90 A 2006:10535), The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning (FORMAS, projects 216-2007-1223 and 216-2009-606), The Swedish Research Council (project 621-2011-3560), the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and the METALUND Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS) Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests.

Authors’ contributions

JL, TS, ABl and ES designed the research; JL, ABe and CB performed the experiments; JL, ABe and JR analyzed the data; JL and ABe wrote the paper. All authors contributed significantly to data evaluation and finalization of the text. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Löndahl, J., Swietlicki, E., Rissler, J. et al. Experimental determination of the respiratory tract deposition of diesel combustion particles in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Part Fibre Toxicol 9, 30 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-9-30

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-9-30