Abstract

Background

Emissions from biomass combustion are a major source of indoor and outdoor air pollution, and are estimated to cause millions of premature deaths worldwide annually. Whilst adverse respiratory health effects of biomass exposure are well established, less is known about its effects on the cardiovascular system. In this study we assessed the effect of exposure to wood smoke on heart rate, blood pressure, central arterial stiffness and heart rate variability in otherwise healthy persons.

Methods

Fourteen healthy non-smoking subjects participated in a randomized, double-blind crossover study. Subjects were exposed to dilute wood smoke (mean particle concentration of 314±38 μg/m3) or filtered air for three hours during intermittent exercise. Heart rate, blood pressure, central arterial stiffness and heart rate variability were measured at baseline and for one hour post-exposure.

Results

Central arterial stiffness, measured as augmentation index, augmentation pressure and pulse wave velocity, was higher after wood smoke exposure as compared to filtered air (p < 0.01 for all), and heart rate was increased (p < 0.01) although there was no effect on blood pressure. Heart rate variability (SDNN, RMSSD and pNN50; p = 0.003, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) was decreased one hour following exposure to wood smoke compared to filtered air.

Conclusions

Acute exposure to wood smoke as a model of exposure to biomass combustion is associated with an immediate increase in central arterial stiffness and a simultaneous reduction in heart rate variability. As biomass is used for cooking and heating by a large fraction of the global population and is currently advocated as a sustainable alternative energy source, further studies are required to establish its likely impact on cardiovascular disease.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01488500

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Exposure to fine and ultrafine combustion-derived particulate air pollution (PM2.5, particulate matter with a mean aerodynamic diameter <2.5 μm) is increasingly recognized as a short and long-term risk factor for cardiovascular disease and has been linked to the triggering of myocardial infarction within hours of exposure [1–5]. Controlled exposure studies have demonstrated that acute exposure to diesel exhaust and concentrated ambient particles, as models of urban particulate air pollution, generate acute vasoconstriction, increases in blood pressure and arterial stiffness [1, 6, 7], vascular endothelial dysfunction [8], myocardial ischemia [8, 9] and changes in cardiac autonomic control [7, 10]. This may in turn explain the observed increase in cardiovascular events [11].

Smoke from biomass combustion is the world’s oldest anthropogenic air pollution and contributes significantly to ambient levels of free radicals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, aldehydes, partially oxidised organic chemicals and particulate matter [12]. Currently more than half the world’s population relies on indoor burning of biomass for heating and cooking [13], and indoor exposure to PM10 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter <10 μm) frequently exceeds concentrations of 1,000 μg/m3 in these settings [12]. This is to be compared to World Health Organization guidelines of annual average PM10 levels <20 μg/m3 and daily averages <50 μg/m3. If particulate air pollution from biomass smoke has similar effects on cardiovascular health as has been shown for other combustion derived air pollutants, this is of major importance for global public health; concerning low-income countries (where indoor open fires are commonplace) and high-income countries (where residential heating from wood stoves is popular) alike.

Although adverse effects on the respiratory system have been demonstrated in epidemiological as well as controlled exposure studies [12, 14, 15], less is known about the effects of biomass smoke on the cardiovascular system. Recent studies highlight associations between biomass air pollution and emergency department visits, hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases [16, 17] and cardiovascular mortality [18–20]. In an interventional study, indoor air pollution from biomass smoke was reduced significantly by replacing open fireplaces with chimney stoves and resulted in significant reductions in blood pressure [21] and myocardial ischemia measured using ambulatory electrocardiography [22].

In this study we tested the hypothesis that a 3-hour exposure to soot-rich wood smoke would cause acute haemodynamic effects evidenced by changes in heart rate, blood pressure, central arterial stiffness, and heart rate variability

Results

Fourteen subjects participated in the study, and their baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1.

At baseline there were no differences in heart rate, blood pressure, arterial stiffness or heart rate variability between exposure days (Table 2). Augmentation index, augmentation pressure and pulse wave velocity were all higher immediately after wood smoke exposure (p < 0.001, p = 0.004 and p = 0.005 respectively) as compared to filtered air (Figure 1). Wood smoke exposure did not affect systolic or diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.858 and p = 0.213 respectively), but did increase heart rate (p = 0.008) over the hour post exposure. Wood smoke exposure decreased general measures of heart rate variability (SDNN, RMSSD and pNN50; p = 0.003, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively) over the hour post exposure. Compared to filtered air, the high frequency domain (HFn) recordings were reduced (p = 0.009), consistent with vagal inhibition, whereas the low frequency domain (LFn) was marginally increased (p=0.086), although did not reach statistical significance Figure 2.

Vascular parameters 10-60 minutes after exposure. Compared to filtered air, wood smoke exposure increased heart rate (p = 0.008), pulse wave velocity (p = 0.005), augmentation index (p < 0.001) and augmentation pressure (p = 0.004), but no effect was seen on brachial systolic (p = 0.858) or diastolic (p = 0.213) blood pressure. All data expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and P-values from 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

Heart rate variability recordings in 10 min intervals 0-60 minutes post exposure. Compared to filtered air, wood smoke exposure decreased the HF domain (p = 0.009), and a small decrease was seen in the LF domain (p = 0.086). All the time domain recordings were reduced following wood smoke exposure as compared to filtered air; SDNN (p = 0.003), RMSSD (p < 0.001) and pNN50 (p < 0.001). All data expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean and P-values from 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

Discussion

In this study, a 3-hour exposure to wood smoke has been shown to simultaneously increase central arterial stiffness and heart rate and reduce heart rate variability, suggesting that wood smoke exposure does have acute haemodynamic effects on the cardiovascular system.

Arterial stiffness

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the acute effects of wood smoke exposure on central arterial stiffness. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting vascular impairment such as increased arterial stiffness after exposure to other air pollutants such as tobacco smoke (including second hand smoke) [23–26] and diesel exhaust [6]. In general, values reflecting arterial stiffness were low, indicating compliant arteries, and blood pressure was in the normal range, as expected in healthy young adults. As predicted, moderate exercise alone increased heart rate and decreased central arterial stiffness [27, 28]. The exposure ends with a resting period within the chamber and the first measurements were taken 10 minutes post exposure. This allows 25 minutes to elapse between the last exercise and the first measurements of brachial blood pressure and arterial stiffness ensuring that the subjects are in a more relaxed state. As the exercise during both exposures was exactly the same, with only the nature of the exposure differing, we conclude that any differences observed in cardiovascular parameters would be a consequence of the wood smoke exposure.

Interestingly, both diesel exhaust and wood smoke appear to have similar acute and transient effects on central arterial stiffness. Following both pollutants, the increase in central arterial stiffness is more pronounced up to 20 minutes after the exposure and seems to decrease with time [6].

Epidemiological studies of exposure to particulate air pollution, however, only partially support a link between air pollution exposure and central arterial stiffness. A recent study including 3,996 subjects in six US cities failed to find an association between estimated average exposure to particulate matter air pollution over 20 years and arterial stiffness [29]. A study on patients that sought medical attention in hypertension outpatient clinics in Athens, Greece found a significant association between 5 day average PM10 and arterial stiffness in males [30]. These results do not necessarily contradict each other as long- and short-term modifiers of arterial stiffness differ. Long term modifiers include degenerative damage of elastin and an increase of collagen in the arterial wall, whereas short term modifications are more likely due to change in arterial tone and vascular endothelial signalling [31]. Arterial tone and vascular endothelial signalling may in turn be altered by factors affected by air pollution, such as the activity of the autonomic nervous system and vascular endothelial function [8, 32].

Heart rate variability

Variations in the interval between consecutive heartbeats are controlled by the autonomous nervous system and can be quantified by measuring heart rate variability. Decreased heart rate variability is a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in healthy individuals [33] as well those with existing cardiovascular disease [34, 35]. In this study we have shown that general measures of heart rate variability are reduced following exposure to wood smoke, which appears predominantly due to a reduction in high frequency components of the spectrum suggesting vagal inhibition. In addition, our data show a small (but non-significant) increase in low frequency components, which may represent an increase in sympathetic activation. The alteration in the balance of autonomic innervation to the vasculature may explain the increased arterial stiffness and acute haemodynamic effects.

Wood smoke has been shown to rapidly trigger pulmonary vagal C-fibres in rats [36] and thereby activate the autonomic nervous system. However, in contrast to our findings, a recent controlled study on 10 healthy volunteers exposed to wood smoke failed to find evidence of an effect on the autonomic nervous system when assessed with heart rate variability [15]. Similarly, an intervention to reduce biomass smoke exposure of Guatemalan women showed reductions in ST-segment depression on electrocardiograms, but no evidence of alterations in heart rate variability [22].

There have been numerous studies addressing changes in heart rate variability following exposures to various air pollutants, including ozone, other gaseous pollutants, diesel exhaust and concentrated ambient particles. Results from these studies have often been contrasting and these inconsistencies may be due to differences in physicochemical properties of different pollutants as well as heterogeneity in study design. In a recent meta-analysis of 29 epidemiological studies comprising 18 667 subjects, Pieters and colleagues report an inverse relationship between heart rate variability in the frequency and time domains and exposure to PM air pollution [37]. Although ambient PM air pollution is derived from many different sources, our finding of a decrease in both the time and frequency domain following wood smoke exposure is in line with the epidemiological data reported by Pieters et al.

Possible underlying mechanisms

Whilst it appears likely that the changes in central arterial stiffness are driven by an alteration in vascular autonomic control, vascular endothelial dysfunction, caused by reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide is a plausible alternative explanation. It is recognized that vascular function is intimately associated with the autonomic nervous system. Vascular dysfunction has been a consistent finding following exposure to concentrated ambient particles and diesel exhaust [8, 38–40]. There have been some preliminary observations suggesting vascular endothelial dysfunction after exposure to wood smoke. One interventional study investigated the effects of HEPA filtration of subjects homes in an area with high levels of wood smoke derived air pollution and showed increased reactive hyperaemia following filtration of the air, suggesting that wood smoke does affect endothelial function [41]. However, a recent controlled wood smoke exposure study failed to show a significant effect on reactive hyperaemia in 20 healthy atopic subjects [42]. Though a credible mechanism, further research is necessary to establish whether endothelial dysfunction is driving the increase in arterial stiffness observed in this study.

The effects of air pollution on blood pressure has been heterogeneous regardless of study type and pollutant [1], and the fact that we did not see any effect on either systolic or diastolic blood pressure may have several explanations. First, our sample size may have been too small. Secondly, if vagal withdrawal increases heart rate, this may obscure an increase in blood pressure. Thirdly, arterial stiffness primarily reflect changes in central capacitance vessels, whereas brachial blood pressure is largely affected by peripheral resistance vessels [43], suggesting an effect of wood smoke on central rather than peripheral vessels.

Study limitations

Biomass smoke is a complex mixture of particles and gaseous components with different physicochemical composition depending on source and combustion characteristics. The smoke from the partially air starved soot rich combustion used in this study may generate a different cardiovascular response as compared to a more efficient combustion in a modern wood stove or even poorer combustion during indoor cooking in low-income countries or combustion of other types of biomass.

Despite there being no significant differences in any cardiovascular measurement pre exposure, the results may have been influenced by regression to the mean as the results are expressed as change prom pre-exposure levels. The randomized double blind design of the study as well as a 20 min resting period prior to baseline measurements help mitigate this type of error.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated for the first time that an acute exposure to wood smoke is associated with an increase in central arterial stiffness and heart rate along with a reduction of heart rate variability. These results imply that wood smoke exposure may be harmful to the cardiovascular system and that these effects are at least partially mediated by the autonomous nervous system. Considering the global prevalence of wood smoke, this calls for further studies investigating wood smoke exposure as a possible risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease as well as mechanistic studies elucidating possible underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Methods

Fourteen non-smoking volunteers completed the study. The subjects underwent a basic screening medical examination and were all healthy with normal electrocardiogram, respiratory function and blood chemistry. None reported any symptoms of respiratory illness at least 6 weeks before or during the study. The study was approved by the local Ethics Review Board, performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki and with the written informed consent of all participants.

Study design

The subjects attended on two separate occasions at least three weeks apart and were exposed to filtered air and diluted wood smoke (target PM1 concentration 300 μg/m3) for 3 hours in a randomized double-blind crossover fashion. During the exposure, the subjects performed intermittent exercise on a bicycle ergometer alternated with rest at 15-minute intervals to achieve an average minute ventilation of 20 L/min/m2. The subjects abstained from alcohol and caffeine 24 hours before the exposure.

Wood smoke exposure

Wood smoke was generated using a common Nordic wood stove (chimney stove) in a controlled incomplete combustion firing procedure. Birch wood logs with a moisture content of 16-18% were inserted every 5-15 minutes to maintain a high burn rate with repeated air-starved conditions. Accordingly, excess oxygen in the flue gases varied from 3 to 17%. Due to the varying combustion conditions, CO concentrations in the flue gases varied from a typical range of 1000-5000 ppm to peaks up to around 12 000 ppm during low excess oxygen (<5%) conditions. In previous studies it has been illustrated that this kind of combustion with high burn rate of wood is associated with high elemental carbon (EC), soot and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) emissions [44].

The wood smoke was diluted with HEPA and activated carbon filtered air in three steps and continuously fed into a controlled environment exposure chamber (15.3 m3) to achieve a steady state concentration. The atmosphere in the chamber was monitored for gaseous pollutants using continuous measurement of nitrogen oxides (NOx) (chemiluminescence, CLD 700 Ecophysics, >0.001 ppm) and carbon monoxide (CO) (IR, UNOR6N Maihak). PM1 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of <1 μm) mass concentration was measured on-line using a tapered element oscillating microbalance (TEOM 1400 by Thermo Scientific) equipped with a PM1 pre-cyclone. Integrated with the TEOM, a filter (Teflon) sampling line was used to determine the particle mass concentration gravimetrically. Within the exposure chamber the diluted wood smoke had an average PM1 concentration (measured with the TEOM) of 314 μg/m3 (range 232 - 356 μg/m3), which was associated with average NOx and CO concentrations of 0.41 ppm and 25 ppm, respectively. Due to the combustion procedure, as described above, the concentration of PM and gases in the chamber did vary, although the aerosol residence time in the chamber (~20 min) compensated for this.

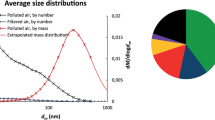

The aerodynamic diameter of the wood smoke particles was measured in the aerosol flow into the chamber using a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS). The SMPS was used for regulating the dilution during exposures to reduce fluctuations in the chamber. Due to the placement of the SMPS, data on particle size and number concentration in the breathing zone of the subjects is not available. At the inlet, the size distribution was bimodal with one peak at around 50 nm and a second peak between 100-200 nm. Previous studies show that the 50 nm peak consist of alkali salt particles (e.g. K2SO4 and KCl) and the 100-200 nm peak consist of a soot mode with more or less organic material [45, 46]. Organic (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) was determined using a thermal-optical carbon analysis (Method NIOSH 5040) [47]. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) were sampled in the chamber by glass fibre filters (Ø 47 mm) for the particulate fraction followed by a polyurethane foam (PUF) plug (Ø 75 mm × 50 mm) for the semi-volatile fraction. PAH compounds (3-6 rings) were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) as described elsewhere [48, 49].

The total carbonaceous (TC) PM of the wood smoke was dominated by EC with a EC/TC ratio of 0.72 ± 0.08. Based on estimation of the components of the total PM in the wood smoke, the PM consisted of 38% soot, 24% organics and the remainder presumably alkali salts. A factor of 1.8 was used to convert the OC content to total organic PM and a factor of 1.1 was used to convert EC to soot PM mass concentration.

The total PAH concentration in the chamber was 1.1 ± 0.7 μg/m3, of which 74% (0.78 μg/m3) was in the particulate phase. The 12 dominating PAH compounds in the PM fraction, accounting for 86±2% of the total analyzed PAH, were (in descending order); Benzo(a)pyrene, Benzo(b)fluoranthene, Benzo(ghi)perylene, Benzo(e)pyrene, Benz(a)anthracene, Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene, Benzo(k)fluoranthene, Benzo(ghi)fluoranthene, Coronene, Pyrene, Perylene and Fluoranthene Table 3.

Arterial stiffness and blood pressure

Vascular studies were performed in a quiet, temperature-controlled room with the subjects resting in a semi-recumbent position. Measurements were performed at baseline (pre exposure), and at 10-minute intervals after the exposure for one hour.

Blood pressure was measured using a validated semi-automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Boso-Medicus, Boso, Jungingen, Germany). Central arterial stiffness measured by pulse wave analysis was determined with a high-fidelity handheld tonometer (Millar Instruments, Texas, USA) at the right radial artery using the SphygmoCor™ system (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, pulse wave analysis derives an aortic pulse wave from a recording at the radial artery and the brachial blood pressure via generalized transfer function [50]. From this, augmentation index and augmentation pressure, both estimates of central arterial stiffness, are calculated. As augmentation index decreases with increased pulse rate due to a shorter ejection duration of the left ventricle [51], all measurements are corrected for pulse rate.

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity is regarded as the current “gold-standard” measurement of central arterial stiffness due to its reproducibility, ease of use and ability to predict cardiovascular events in several large trials [43, 52, 53]. Pulse wave velocity measurements were made using the Vicorder system (Skidmore Medical, UK), which detects the pressure wave simultaneously at the carotid and femoral arteries using inflatable cuffs. The pulse transit time between these sites is calculated by identifying the arrival of the foot of the pulse wave using a proprietary intersecting tangents algorithm as compared to the R-wave on the electrocardiogram. The distance between the sites divided by pulse transit time is then used to generate pulse wave velocity.

Heart rate variability

Continuous 3-lead electrocardiographic recordings were obtained through the study period using a Holter monitor (Spacelabs 90217, Spacelabs, UK). Heart rate variability and heart rate was determined from the electrocardiographic recordings using the Reynolds Medical Pathfinder Digital 700 Series Analysis System (Delmar Reynolds, UK) and the HRV Tools software package (Delmar Reynolds, UK) pre exposure and at 10-minute intervals over the hour post exposure. Standard time domain measures were calculated including the mean NN interval (time interval between consecutive sinus beats), SD of NN interval values (SDNN), percentage successive NN interval differences >50 ms (pNN50), root mean square of successive NN interval differences (RMSSD) and the triangular index. Frequency domain analysis included the low frequency (LF) and high frequency (HF) components of the power spectrum. LF and HF and are expressed in normalised units (LFn and HFn), to account for variation in the total power as well as the HF/LF ratio. No geometrical methods are reported for the 10 minute intervals over the hour post exposure due to the difficulties obtaining accurate measurements of these indices from short term recordings [54].

Statistical analysis

All data was analysed using GraphPad Prism, version 5.0, (GraphPad Software, USA) by 2-tailed paired Student’s t-test, Wilcoxon signed rank test and 2 way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures where appropriate. Statistical significance was taken at P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) or median with inter quartile range. All data analysis was made prior to unbinding the nature of the exposures.

To avoid bias from day to day variations in blood pressure, arterial stiffness and heart rate variability, all measurements over the hour post exposure are expressed as change from baseline taken prior to each exposure. Post exposure values were all normally distributed (D’Agostino-Pearson normality test).

Abbreviations

- PM:

-

Particulate matter

- PM1:

-

Particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter <1 μm

- PM2.5:

-

Particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter <2.5 μm

- OC:

-

Organic carbon

- EC:

-

Elemental carbon

- PAH:

-

Polyaromatic hydrocarbons

- SMPS:

-

Scanning mobility particle sizer

- TEOM:

-

Tapered element oscillating microbalance

- NN:

-

Interval between consecutive heart beats

- SDNN:

-

Standard deviation of the NN interval

- RMSSD:

-

The square root of the mean squared differences of successive NN intervals

- pNN50:

-

Percentage of successive NN intervals greater than 50 ms

- HF:

-

High frequency component of heart rate variability

- LF:

-

Low frequency component of heart rate variability.

References

Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, et al.: Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121: 2331–2378. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1

Peters A, von Klot S, Heier M, Trentinaglia I, Hörmann A, Wichmann HE, Löwel H, Group CHRitRoAS: Exposure to traffic and the onset of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2004, 351: 1721–1730. 10.1056/NEJMoa040203

Pope CA, Muhlestein JB, May HT, Renlund DG, Anderson JL, Horne BD: Ischemic heart disease events triggered by short-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. Circulation 2006, 114: 2443–2448. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.636977

Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Armstrong B, Haines A, Herrett E, Wilkinson P, Smeeth L: The effects of hourly differences in air pollution on the risk of myocardial infarction: case crossover analysis of the MINAP database. BMJ 2011, 343: d5531. 10.1136/bmj.d5531

Nawrot TS, Perez L, Künzli N, Munters E, Nemery B: Public health importance of triggers of myocardial infarction: a comparative risk assessment. Lancet 2011, 377: 732–740. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62296-9

Lundbäck M, Mills N, Lucking A, Barath S, Donaldson K, Newby D, Sandström T, Blomberg A: Experimental exposure to diesel exhaust increases arterial stiffness in man. Part Fibre Toxicol 2009, 6: 7. 10.1186/1743-8977-6-7

Brook RD, Urch B, Dvonch JT, Bard RL, Speck M, Keeler G, Morishita M, Marsik FJ, Kamal AS, Kaciroti N, et al.: Insights into the mechanisms and mediators of the effects of air pollution exposure on blood pressure and vascular function in healthy humans. Hypertension 2009, 54: 659–667. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130237

Mills N, Törnqvist H, Robinson S, Gonzalez M, Darnley K, MacNee W, Boon N, Donaldson K, Blomberg A, Sandstrom T, Newby D: Diesel exhaust inhalation causes vascular dysfunction and impaired endogenous fibrinolysis. Circulation 2005, 112: 3930–3936. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588962

Mills NL, Tornqvist H, Gonzalez MC, Vink E, Robinson SD, Soderberg S, Boon NA, Donaldson K, Sandstrom T, Blomberg A, Newby DE: Ischemic and thrombotic effects of dilute diesel-exhaust inhalation in men with coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2007, 357: 1075–1082. 10.1056/NEJMoa066314

Sivagangabalan G, Spears D, Masse S, Urch B, Brook RD, Silverman F, Gold DR, Lukic KZ, Speck M, Kusha M, et al.: The effect of air pollution on spatial dispersion of myocardial repolarization in healthy human volunteers. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011, 57: 198–206. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.625

Langrish JP, Bosson J, Unosson J, Muala A, Newby DE, Mills NL, Blomberg A, Sandström T: Cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution exposure: time course and underlying mechanisms. J Intern Med 2012, 272: 224–239. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02566.x

Naeher L, Brauer M, Lipsett M, Zelikoff J, Simpson C, Koenig J, Smith K: Woodsmoke health effects: a review. Inhal Toxicol 2007, 19: 67–106.

WHO: Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: Department of Health Statistics and Informatics in the Information, Evidence and Research Cluster of the World Health Organization; 2009.

Po JY, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C: Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2011, 66: 232–239. 10.1136/thx.2010.147884

Ghio AJ, Soukup JM, Case M, Dailey LA, Richards J, Berntsen J, Devlin RB, Stone S, Rappold A: Exposure to wood smoke particles produces inflammation in healthy volunteers. Occup Environ Med 2011, 69: 170–175.

McGowan JA, Hider RN, Chacko E, Town GI: Particulate air pollution and hospital admissions in Christchurch, New Zealand. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002, 26: 23–29. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00266.x

Rappold AG, Stone SL, Cascio WE, Neas LM, Kilaru VJ, Carraway MS, Szykman JJ, Ising A, Cleve WE, Meredith JT, et al.: Peat bog wildfire smoke exposure in rural north carolina is associated with cardio-pulmonary emergency department visits assessed through syndromic surveillance. Environ Health Perspect 2011, 119: 1415–1420. 10.1289/ehp.1003206

Johnston F, Hanigan I, Henderson S, Morgan G, Bowman D: Extreme air pollution events from bushfires and dust storms and their association with mortality in Sydney, Australia 1994–2007. Environ Res 2011, 111: 811–816. 10.1016/j.envres.2011.05.007

Sanhueza PA, Torreblanca MA, Diaz-Robles LA, Schiappacasse LN, Silva MP, Astete TD: Particulate air pollution and health effects for cardiovascular and respiratory causes in Temuco, Chile: a wood-smoke-polluted urban area. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 2009, 59: 1481–1488. 10.3155/1047-3289.59.12.1481

Analitis A, Georgiadis I, Katsouyanni K: Forest fires are associated with elevated mortality in a dense urban setting. Occup Environ Med 2011, 69: 158–162.

McCracken JP, Smith KR, Díaz A, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J: Chimney stove intervention to reduce long-term wood smoke exposure lowers blood pressure among Guatemalan women. Environ Health Perspect 2007, 115: 996–1001. 10.1289/ehp.9888

McCracken J, Smith KR, Stone P, Díaz A, Arana B, Schwartz J: Intervention to lower household woodsmoke exposure in guatemala reduces ST-segment depression on electrocardiograms. Environ Health Perspect 2011, 119: 1562–1568. 10.1289/ehp.1002834

Doonan RJ, Hausvater A, Scallan C, Mikhailidis DP, Pilote L, Daskalopoulou SS: The effect of smoking on arterial stiffness. Hypertens Res 2010, 33: 398–410. 10.1038/hr.2010.25

Barnoya J, Glantz SA: Cardiovascular effects of secondhand smoke: nearly as large as smoking. Circulation 2005, 111: 2684–2698. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.492215

Vlachopoulos C, Alexopoulos N, Panagiotakos D, O’Rourke MF, Stefanadis C: Cigar smoking has an acute detrimental effect on arterial stiffness. Am J Hypertens 2004, 17: 299–303. 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.12.014

Frey PF, Ganz P, Hsue PY, Benowitz NL, Glantz SA, Balmes JR, Schick SF: The exposure-dependent effects of aged secondhand smoke on endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 59: 1908–1913. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.025

Collier SR, Diggle MD, Heffernan KS, Kelly EE, Tobin MM, Fernhall B: Changes in arterial distensibility and flow-mediated dilation after acute resistance vs. aerobic exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24: 2846–2852. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840e0

Figueroa A, Vicil F: Post-exercise aortic hemodynamic responses to low-intensity resistance exercise with and without vascular occlusion. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2011, 21: 431–436. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01061.x

O’Neill MS, Diez-Roux AV, Auchincloss AH, Shen M, Lima JA, Polak JF, Barr RG, Kaufman J, Jacobs DR: Long-term exposure to airborne particles and arterial stiffness: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect 2011, 119: 844–851. 10.1289/ehp.0901524

Adamopoulos D, Vyssoulis G, Karpanou E, Kyvelou SM, Argacha JF, Cokkinos D, Stefanadis C, van de Borne P: Environmental determinants of blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and central hemodynamics. J Hypertens 2010, 28: 903–909. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283369f67

Zieman SJ, Melenovsky V, Kass DA: Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and therapy of arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005, 25: 932–943. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000160548.78317.29

Link MS, Dockery DW: Air pollution and the triggering of cardiac arrhythmias. Curr Opin Cardiol 2010, 25: 16–22. 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32833358cd

Tsuji H, Larson MG, Venditti FJ, Manders ES, Evans JC, Feldman CL, Levy D: Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 1996, 94: 2850–2855. 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2850

Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF: The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol 2010, 141: 122–131. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.543

Kleiger RE, Miller JP, Bigger JT, Moss AJ: Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1987, 59: 256–262. 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8

Lai CJ, Kou YR: Stimulation of vagal pulmonary C fibers by inhaled wood smoke in rats. J Appl Physiol 1998, 84: 30–36.

Pieters N, Plusquin M, Cox B, Kicinski M, Vangronsveld J, Nawrot TS: An epidemiological appraisal of the association between heart rate variability and particulate air pollution: a meta-analysis. Heart 2012, 98: 1127–1135. 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301505

Barath S, Mills N, Lundbäck M, Törnqvist H, Lucking A, Langrish J, Söderberg S, Boman C, Westerholm R, Löndahl J, et al.: Impaired vascular function after exposure to diesel exhaust generated at urban transient running conditions. Part Fibre Toxicol 2010, 7: 19. 10.1186/1743-8977-7-19

Peretz A, Sullivan JH, Leotta DF, Trenga CA, Sands FN, Allen J, Carlsten C, Wilkinson CW, Gill EA, Kaufman JD: Diesel exhaust inhalation elicits acute vasoconstriction in vivo. Environ Health Perspect 2008, 116: 937–942. 10.1289/ehp.11027

Törnqvist H, Mills NL, Gonzalez M, Miller MR, Robinson SD, Megson IL, Macnee W, Donaldson K, Söderberg S, Newby DE, et al.: Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007, 176: 395–400. 10.1164/rccm.200606-872OC

Allen RW, Carlsten C, Karlen B, Leckie S, Eeden S, Vedal S, Wong I, Brauer M: An air filter intervention study of endothelial function among healthy adults in a woodsmoke-impacted community. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011, 183: 1222–1230. 10.1164/rccm.201010-1572OC

Forchhammer L, Moller P, Riddervold IS, Bonlokke J, Massling A, Sigsgaard T, Loft S: Controlled human wood smoke exposure: oxidative stress, inflammation and microvascular function. Part Fibre Toxicol 2012, 9: 7. 10.1186/1743-8977-9-7

Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H, Arteries ENfN-iIoL: Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 2006, 27: 2588–2605. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254

Pettersson E, Boman C, Westerholm R, Boström D, Nordin A: Stove performance and emission characteristics in residential wood log and pellet combustion, part 2: wood stove. Energy Fuel 2011, 25: 315–323. 10.1021/ef1007787

Löndahl J, Pagels J, Boman C, Swietlicki E, Massling A, Rissler J, Blomberg A, Bohgard M, Sandström T: Deposition of biomass combustion aerosol particles in the human respiratory tract. Inhal Toxicol 2008, 20: 923–933. 10.1080/08958370802087124

Lamberg H, Nuutinen K, Tissari J, Ruusunen J, Yli-Pirilä P, Sippula O, Tapanainen M, Jalava P, Makkonen U, Teinilä K, et al.: Physicochemical characterization of fine particles from small-scale wood combustion. Atmos Environ 2011, 45: 7635–7643. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.02.072

Turpin BJ, Saxena P, Andrews E: Measuring and simulating particulate organics in the atmosphere: problems and prospects. Atmos Environ 2000,34(18):2983–3013. 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00501-4

Alsberg T, Stenberg U, Westerholm R, Strandell M, Rannug U, Sundvall A, Romert L, Bernson V, Pettersson B, et al.: Chemical and biological characterization of organic material from gasoline exhaust particles. Environ Sci Tech 1985, 19: 43–50. 10.1021/es00131a003

Boman C, Nordin A, Westerholm R, Pettersson E: Evaluation of a constant volume sampling setup for residential biomass fired appliances—influence of dilution conditions on particulate and PAH emissions. Biomass Bioenergy 2005, 29: 258–268. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.03.003

Karamanoglu M, O’Rourke MF, Avolio AP, Kelly RP: An analysis of the relationship between central aortic and peripheral upper limb pressure waves in man. Eur Heart J 1993, 14: 160–167. 10.1093/eurheartj/14.2.160

Wilkinson IB, MacCallum H, Flint L, Cockcroft JR, Newby DE, Webb DJ: The influence of heart rate on augmentation index and central arterial pressure in humans. J Physiol 2000,525(Pt 1):263–270.

Boutouyrie P, Tropeano A, Asmar R, Gautier I, Benetos A, Lacolley P, Laurent S: Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertension 2002, 39: 10–15. 10.1161/hy0102.099031

Cecelja M, Chowienczyk P: Dissociation of aortic pulse wave velocity with risk factors for cardiovascular disease other than hypertension: a systematic review. Hypertension 2009, 54: 1328–1336. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.137653

Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology Circulation 1996, 93: 1043–1065. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the nurses Annika Johansson and Frida Holmström at the Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine at University Hospital, Umeå for their invaluable assistance with these studies. Thanks also to Esbjörn Pettersson and the technical staff at the Thermochemical Energy Conversion Laboratory, Department of Applied Physics and Electronics, Umeå University for their expertise in designing and running the exposure facility. Thanks also to Christoffer Bergvall at the Arrhenius Laboratory, Stockholm University, for performing PAH analysis. This work was supported by the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the Swedish Clean Air Research Program, Umeå University, Västerbotten County Council and the British Heart Foundation by a programme grant (RG/10/9/28286). NLM is supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Clinical Research Fellowship (FS/10/024/28266).

Support

Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, Swedish Clean Air Research Program, British Heart Foundation, Umeå University, Västerbotten County Council

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AB, TS, NM, DN, JL and JB conceived and participated in the design of the study. JU, AM and JB carried out the clinical studies and collected the data. JU, JB and JL performed the data analysis and statistical analysis. CB and RN generated the clinical exposures and performed analysis of the exposure variables along with RW. JU drafted the manuscript and all authors were involved in critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Unosson, J., Blomberg, A., Sandström, T. et al. Exposure to wood smoke increases arterial stiffness and decreases heart rate variability in humans. Part Fibre Toxicol 10, 20 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-10-20

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-10-20