Abstract

Background

HBV-X protein is associated with the pathogenesis of HBV related diseases, specially in hepatocellular carcinomas of chronic patients. Genetic variability of the X gene includes genotypic specific variations and mutations emerging during chronic infection. Its coding sequence overlaps important regions for virus replication, including the basal core promoter. Differences in the X gene may have implications in biological functions of the protein and thus, affect the evolution of the disease. There are controversial results about the consequences of mutations in this region and their relationship with pathogenesis. The purpose of this work was to describe the diversity of HBV-X gene in chronic hepatitis patients infected with different genotypes, according to liver disease.

Methods

HBV-X gene was sequenced from chronic hepatitis B patient samples, analyzed by phylogeny and genotyped. Nucleotide and aminoacid diversity was determined calculating intragenetic distances. Mutations at 127, 130 and 131 aminoacids were considered in relation to liver disease.

Results

The most prevalent genotype detected in this cohort was F (F1 and F4), followed by D and A. Most of the samples corresponding to genotypes A and F1 were HBeAg(+) and for genotypes D and F4, HBeAg(−) samples were represented in a higher percentage. Intragenetic distance values were higher in HBeAg(−) than in positive samples for all genotypes, and lower in overlapped regions, compared to single codification ones. Nucleotide and aminoacid diversities were higher in HBeAg(−), than in HBeAg(+) samples.

Conclusions

Independently of the infecting genotypes, mutations at any of 127, 130 and/or 131 aminoacid positions and HBeAg(−) status were associated with mild liver disease in this cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family and can be classified into eight genotypes (A to H). The viral genome has four overlapped open reading frames (ORFs) that codify for: envelope (S/Pre-S), core (C/pre-C), polymerase (P) and X (HBV-X) proteins [1, 2]. HBV-X is a 154 aminoacid multifunctional protein with transcriptional transactivator activity on a number of cellular and viral promoters. HBV-X has been associated with the pathogenesis of HBV related diseases, especially in the occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic patients [3–6]. The compact nature of the genome and the ORFs overlapping lead to a “constrained evolution” of the virus [7, 8]. Genetic variability of the X gene includes genotypic specific variations and mutations emerging during chronic infection [9–14]. Its coding sequence overlaps important regions for virus replication, including the basal core promoter (BCP). Thus, a mutation on the X gene may not only induce aminoacid changes in HBV-X, but also can affect other genes and modify HBV expression [15–17]. In addition, differences in the X gene may have implications in the biological functions of the protein and thus, affect the evolution of the disease [18–21].

During chronic HBV infection, two phases can be distinguished: a first phase characterized by high viral load, HBeAg(+) and high aminotransferases activity; and a second phase with detectable HBV-DNA by PCR, HBeAg(−), detectable anti-HBe antibodies, and normal aminotransferases levels [22, 23]. However, there are anti-HBeAg patients who have high ALT levels and detectable serum HBV-DNA, because of BCP mutations.

Natural mutations in the HBV-X gene have been related to the progression of chronic liver disease due to the recession of anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects on the infected hepatocytes, contributing to carcinogenesis [24, 25]. Although, there are controversial results about the consequences of mutations in this region and their relationship with pathogenesis [26].

Different studies have failed to find a correlation between BCP mutations (1762–64 nucleotidic positions), viral replication and liver damage in chronic hepatitis B (CHB). The contradictory data may reflect differences between the studied populations (genotype distribution, HBeAg status, clinical stage of the patients). The pathogenic role of BCP mutations in CHB and their role in the progression of liver disease is still under debate. Among “hot spot” mutations with impact on HBV-X biological activities, I127T should also be considered [19].

The aims of this work were to study the diversity of HBV-X gene and its protein in CHB patients infected with different genotypes, determine the prevalence of 127, 130 and 131 aminoacid mutations and describe their relationship with liver biopsy in an infected cohort of our geographic area.

Methods

Patients and samples

Thirty-two serum samples from chronic HBV patients, who were assisted at “Unidad de Hepatopatías Infecciosas” from Hospital Francisco Muñiz, Buenos Aires, were included in this study. Biochemical tests were carried out with routine automated methods. HBsAg, HBeAg, anti-HBe and anti-HBs were measured using commercial kits (MEIA, Axsym, Abbott Laboratories). Serum HBV DNA levels were quantified by an Amplicor HBV Monitor Test (Roche), following the manufacturer´s instructions. Liver biopsy specimens were evaluated according to the modified Knodell score, and categorized as mild or severe fibrosis (F ≤ 2 or F > 2, respectively). All patients were negative for HCV and HIV antibodies. None of the included patients had received antiviral treatment for their chronic hepatitis. This research has complied with all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies. It was carried out in complaince with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Pharmacy and Biochemistry, University of Buenos Aires (Protocol Number: 701283). Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all the patients.

PCR amplification and sequencing of the X gene

DNA was extracted from 200 μL serum samples with a QIAmp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer´s recommendations. For sequencing , the X region of the genome was amplified by nested PCR. Primers used for the first round were: sense 5´TGCCAAGTGTTTGCTGACGC3´ and antisense 5´ACGGGAAGAAATCAGAAGG3´, and for the second round: sense 5´GCCGATCCATACTGCGGAACT3´ and antisense 5´GGCACAGCTTGGAGGCTTGAA3´. First round PCR was performed with 10 μL of DNA in a 50 μL reaction mixture containing 10X buffer, 200 μM dNTPs, 20 mM Cl2Mg, 25 pmol of each primer and 1 U Taq polymerase (Invitrogen). PCR was performed as follows: 94°C 5 min; 94°C 1 min, 45°C 1 min, 72°C 2 min for 45 cycles; and finally 72°C for 10 min. For the second round, 2 μL of the first round PCR product was re-amplified using the same reaction mixture composition, except that internal primers were used. PCR was performed as follows: 94°C 5 min; 94°C 1 min, 55°C 1 min, 72°C 2 min for 40 cycles; and finally 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were run on 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and evaluated under UV light. The amplified products were gel purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). The purified products were sequenced by Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, Korea), using sense and antisense internal primers.

Phylogenetic analysis

Analysis was performed by comparison of the obtained gene sequences, with HBV reference sequences for each genotype, available at GenBank. HBV-X sequences were aligned using ClustalX software 1.81 version [27]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using PAUP4b10 package [28] and MODELTEST 3–06 version [29]. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Maximum Likelihood and Neighbour Joining methods. Robustness of the phylogenetic analysis was evaluated by a 10000 bootstrap resampling. Genetic distances were calculated using the Tamura Nei model of nucleotide substitution, with a gamma distribution of rate heterogeneity between sites, included in MEGA3.1 package. The gamma parameter was determined by using the MODELTEST program.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

Nucleotide sequences analyzed in this work have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers: [GenBank: JF911665 to JF911696].

Results and discussion

1. The main characteristics of the studied patients are shown in Table 1.

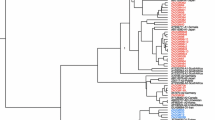

2. Phylogenetic analysis and genotyping To asses genotype distribution in this cohort, genotyping was performed by phylogeny. The phylogenetic analysis grouped the 32 HBV-X gene sequences as: genotype A, 25.0% (n = 8), D 34.4% (n = 11) and F 40.6% (n = 13) (Figure 1). All genotype A sequences were ascribed to subgenotype A2. Genotype F sequences were defined as subgenotype F1b (38.5%, n = 5) and F4 (61.5%, n = 8). Genotype D sequences presented two monophyletic groups corresponding to subgenotype D1 and D3.In summary, the phylogenetic analysis showed that the most prevalent genotype of this sample was F, followed by D and A. These results are in agreement with other previous studies of HBV genotypes distribution in Argentina, in which genotype F, the new world genotype, was the most prevalent, followed by the European genotypes D and A, introduced by migration [30–32].

3. HBeAg status according to genotypes We assessed the prevalence of HBeAg positive or negative phases during chronic HBV infection, in each genotype. The distribution of HBeAg positive (17) and negative (15) samples, according to their genotype showed that most of the A2 and F1b subgenotypes samples were HBeAg(+): (62.5% (5/8) and 100% (5/5), respectively. On the contrary, HBeAg(−) samples were more abundant for genotypes D and F4 (63.6% (7/11) and 62.5% (5/8), respectively (Table 1). All the analyzed sequences appeared intermingled in the phylogenetic tree, independently from their HBeAg status. In summary, genotypes A and F1 showed higher percentage of HBeAg positive samples than negative, and genotypes D and F4 showed higher HBeAg negative than positive samples. The presence of 1858T (characteristic for genotype D) but not 1858C (characteristic for genotype A) facilitates the fixation of the 1896A mutation, stabilizing the encapsidation signal [33–35]. The 1896A mutation abrogates HBeAg expression, establishing the HBeAg(−) phenotype. Interestingly, in this sample F1b subtype resembles to genotype A and F4 subgenotype behaves as genotype D.

4. Nucleotide sequence analysis and X gene diversity Distance models tree topology suggests a different diversification for HBeAg(+) and HBeAg(−) sequences. To assess X gene diversity, an analysis of diversification was carried out calculating the intragroup genetic distances (igds). The non-overlapped X gene region with pol gene (nt 1622–1835) and the over-lapped region (nt 1374–1621) within each genotype were analyzed considering their HBeAg status. Independently of genotypes, HBeAg(−) samples showed higher igd values than the respective HBeAg(+) ones (Table 2). HBeAg(−) samples present a higher diversity compared to HBeAg(+) samples. This result is in agreement with the idea that mutations are generated during the natural course of infection and HBeAg(−) samples, with longer infection periods, have the opportunity to accumulate more nucleotide changes. In addition, single codification regions present higher igds than double codification regions, suggesting different functional constraints due to the genomic organization of HBV [7, 8]. In particular, nucleotides appearing in 1762/1764 positions (BCP) are shown in Table 1. Among all the studied samples (with liver histology data), 8 presented mutations in one or both of these positions. Considering liver disease in patients with mutated X genes, a marked higher proportion of patients with mutations at any of 1762/1764 nucleotides showed mild liver histology (6 out of 8, 75%) and only 2 of 8 (25%) showed severe liver disease. When analyzing the 20 samples with wild type 1762/64 nucleotides, more patients showed mild liver histology (12 out of 20, 60%) than severe liver disease (8 out of 20, 40%), but this difference was not significant. These results can suggest a relation between mutants and slow progression to hepatic disease in this cohort [36].

5. Amino acid diversity of the X protein, mutations in 127/130/131 positions and HBeAg status related to liver disease To assess X protein diversity, an analysis of diversification was carried out calculating aminoacid divergence values. Total amino acid divergence was determined considering the complete X protein (Table 2). HBeAg(−) samples showed higher aminoacid divergence values, compared to HBeAg(+), in agreement with the obtained nucleotide diversity values, independently of genotypes.

The diversification at the amino acid level was analyzed in particular for 127, 130 and 131 positions. Aminoacid diversities at these positions in all groups are shown in Table 1. The samples that present mutations at any of the three studied positions (14/28 with liver histology data) were more associated with mild biopsies (10/14, 71%) than to severe ones (4/14, 29%). When analyzing the 14 samples with wild type amino acids, more patients showed mild liver histology (8 out of 14, 57%) than severe liver disease (6 out of 14, 43%) but the differences between groups were not so pronounced as in the mutant samples.

Independently of the HBeAg status, higher percentages of mild liver pathology than severe one was observed in both groups: 9/15 (60%) for HBeAg(+) and 9/13 (69%) for HBeAg(−). When considering together the HBeAg status, mutants and liver pathology, the wild type HBeAg(+) group showed similar numbers for mild or severe hepatic histology (6 and 5 out of 11, respectively). But, for the mutant HBeAg(−) group, 7 out of 10 (70%) presented mild biopsies (Table 3).

These results suggest that in this particular cohort, mutations at the studied positions, associated with a HBeAg(−) status, give certain protection to evolve to more severe liver pathology, suggesting protective roles in the progression of disease [37]. The results obtained in this work and in this particular studied population do not agree with previous findings that associated 127, 130 and 131 X protein mutations with severity of disease [38–42]. These findings justify further similar studies in large cohorts of patients.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the distribution of HBV genotypes in the studied samples showed genotype F as the most prevalent, followed by D and A. Most of A2 and F1 subgenotype samples were HBeAg(+), but for D and F4 genotypes HBeAg(−) samples were more abundant. Considering X gene and protein variability, HBeAg(−) samples showed higher diversity compared to positive samples. Finally, samples with mutations at any of 127, 130 and/or 131 aminoacid positions and HBeAg(−) status could be associated with mild liver disease.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- BCP:

-

Basal core promoter

- CHB:

-

Chronic hepatitis B

- C:

-

Core

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- dNTPs:

-

Deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates

- HBeAg:

-

Hepatitis B virus “e” antigen

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B virus “s” antigen

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HBV-X:

-

Hepatitis B virus X protein

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- Igds:

-

Intragenetic distances

- nt:

-

Nucleotide

- P:

-

Polymerase

- S:

-

Surface

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction.

References

Hollinger FB, Liang TJ, et al.: Hepatitis B virus. In Fields Virology. 4th edition. Edited by: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, PA; 2001:2971-3036.

Locarnini S: Molecular virology of hepatitis B virus. Semin Liver Dis 2004,24(Suppl1):3-10.

Chemin I, Zoulim F: Hepatitis B virus induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2009, 286: 52-59.

Chen WN, Oon CJ, Leong AL, Koh S, Teng SW: Expression of integrated hepatitis B virus X variants in human hepatocellular carcinomas and its significance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 276: 885-892.

Chen GG, Li MY, Ho RL, Chak EC, Lau WY, Lai PB: Identification of hepatitis B virus X gene mutation in Hong Kong patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Virol 2005, 34: 7-12.

Koike K: Hepatitis B virus X gene is implicated in liver carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett 2009, 286: 60-68.

Kay A, Zoulim F: Hepatitis B virus genetic variability and evolution. Virus Res 2007, 127: 164-176.

Mizokami M, Orito E, Ohba K, Ikeo K, Lau JY, Gojobori T: Constrained evolution with respect to gene overlap of hepatitis B virus. J Mol Evol 1997, 44: S83-S90.

Kidd-Ljunggren K, Miyakawa Y, Kidd AH: Genetic variability in hepatitis B viruses. J Gen Virol 2002, 83: 1267-1280.

Kidd-Ljunggren K, Myhre E, Blackberg J: Clinical and serological variation between patients infected with different Hepatitis B virus genotypes. J Clin Microbiol 2004, 42: 5837-5841.

Venard V, Corsaro D, Kajzer C, Bronowicki JP, Le Faou A: Hepatitis B virus X gene variability in French-born patients with chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol 2000, 62: 177-184.

Lindh M, Hannoun C, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G, Horal P: Core promoter mutations and genotypes in relation to viral replication and liver damage in East Asian hepatitis B virus carriers. J Infect Dis 1999, 179: 775-782.

Song BC, Cui XJ, Kim HU, Cho YK: Sequential accumulation of the basal core promoter and the precore mutations in the progression of hepatitis B virus-related chronic liver disease. Intervirology 2006, 49: 266-273.

Sumi H, Yokosuka O, Seki N, Arai M, Imazeki F, Kurihara T, Kanda T, Fukai K, Kato M, Saisho H: Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the progression of chronic type B liver disease. Hepatology 2003, 37: 19-26.

Buckwold VE, Xu Z, Chen M, Yen TS, Ou JH: Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J Virol 1996, 70: 5845-5851.

Baumert TF, Marrone A, Vergalla J, Liang TJ: Naturally occurring mutations define a novel function of the hepatitis B virus core promoter in core protein expression. J Virol 1998, 72: 6785-6795.

Scaglioni PP, Melegari M, Wands JR: Biologic properties of hepatitis B viral genomes with mutations in the precore promoter and precore open reading frame. Virology 1997, 233: 374-381.

Kreutz C: Molecular, immunological and clinical properties of mutated hepatitis B viruses. J Cell Mol Med 2002, 6: 113-143.

Datta S, Banerjee A, Chandra PK, Biswas A, Panigrahi R, Mahapatra PK, Panda CK, Chakrabarti S, Bhattacharya SK, Chakravarty R: Analysis of hepatitis B virus X gene phylogeny, genetic variability and its impact on pathogenesis:implications in Eastern Indian HBV carriers. Virology 2008, 382: 190-198.

Kidd-Ljunggren K, Oberg M, Kidd AH: Hepatitis B virus X gene 1751 to 1764 mutations: implications for HBeAg status and disease. J Gen Virol 1997, 78: 1469-1478.

Tanaka Y, Mizokami M: Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus as an important factor associated with differences in clinical outcomes. J Infect Dis 2007, 195: 1-4.

Brunetto MR, Giarin M, Oliveri F, Chiaberge E, Baldi M, Alfarano A, Serra A, Saracco G, Verme G, Will H, et al.: Wild-type and e antigen-minus hepatitis B viruses and course of chronic hepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 88: 4186-4190.

Chu CM, Yeh CT, Lee CS, Sheen IS, Liaw YF: Precore stop mutant in HBeAg-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B: clinical characteristics and correlation with the course of HBeAg-to-anti-HBe seroconversion. J Clin Microbiol 2002, 40: 16-21.

Shinkai N, Tanaka Y, Ito K, Mukaide M, Hasegawa I, Asahina Y, Izumi N, Yatsuhashi H, Orito E, Joh T, Mizokami M: Influence of hepatitis B virus X and core promoter mutations on hepatocellular carcinoma among patients infected with subgenotype C2. J Clin Microbiol 2007, 45: 3191-3197.

Yeh CT, Shen CH, Tai DI, Chu CM, Liaw YF: Identification and characterization of a prevalent hepatitis B virus X protein mutant in Taiwanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2000, 19: 5213-5220.

Choi CS, Cho EY, Park R, Kim SJ, Cho JH, Kim HC: X gene mutations in hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis, with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol 2009, 81: 1721-1725.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG: The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25: 4876-4882.

Swofford DL: PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4.0b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts; 2003.

Posada D, Crandall KA: MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 1998, 14: 817-818.

Leone FG P, Pezzano SC, Torres C, Rodriguez CE, Eugenia Garay M, Fainboim HA, Remondegui C, Sorrentino AP, Mbayed VA, Campos RH: Hepatitis B virus genetic diversity in Argentina: dissimilar genotype distribution in two different geographical regions; description of hepatitis B surface antigen variants. J Clin Virol 2008, 42: 381-388.

Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Visona KA, Magnius LO: Genotype F prevails in HBV infected patients of hispanic origin in Central America and may carry the precore stop mutant. J Med Virol 1997, 51: 305-312.

Pezzano SC, Torres C, Fainboim HA, Bouzas MB, Schroder T, Giuliano SF, Paz S, Alvarez E, Campos RH, Mbayed VA: Hepatitis B virus in Buenos Aires, Argentina: genotypes, virological characteristics and clinical outcomes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011, 17: 223-231.

Lok AS, Akarca U, Greene S: Mutations in the pre-core region of hepatitis B virus serve to enhance the stability of the secondary structure of the pre-genome encapsidation signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91: 4077-4081.

Tong SP, Li JS, Vitvitski L, Kay A, Treépo C: Evidence for a base-paired region of hepatitis B virus pregenome encapsidation signal which influences the patterns of precore mutations abolishing HBe protein expression. J Virol 1993, 67: 5651-5655.

Lindh M, Andersson AS, Gusdal A: Genotypes, nt 1858 variants, and geographic origin of hepatitis B virus-large-scale analysis using a new genotyping method. J Infect Dis 1997, 175: 1285-1293.

Jardi R, Rodriguez F, Buti M, Costa X, Valdes A, Allende H, Schaper M, Galimany R, Esteban R, Guardia J: Mutations in the basic core promoter region of hepatitis B virus. Relationship with precore variants and HBV genotypes in a Spanish population of HBV carriers. J Hepatol 2004, 40: 507-514.

Kawabe N, Hashimoto S, Harata M, Nitta Y, Murao M, Nakano T, Shimazaki H, Arima Y, Komura N, Kobayashi K, Yoshioka K: The loss of HBeAg without precore mutation results in lower HBV DNA levels and ALT levels in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol 2009, 44: 751-756.

Fang ZL, Yang J, Ge X, Zhuang H, Gong J, Li R, Ling R, Harrison TJ: Core promoter mutations (A(1762)T and G(1764)A) and viral genotype in chronic hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma in Guangxi, China. J Med Virol 2002, 68: 33-40.

Grandjacques C, Pradat P, Stuyver L, Chevallier M, Chevallier P, Pichoud C, Maisonnas M, Trépo C, Zoulim F: Rapid detection of genotypes and mutations in the pre-core promoter and the pre-core region of hepatitis B virus genome: correlation with viral persistence and disease severity. J Hepatol 2000, 33: 430-439.

Gunther S, Piwon N, Iwanska A, Schilling R, Meisel H, Will H: Type, prevalence, and significance of core promoter/enhancer II mutations in hepatitis B viruses from immunosuppressed patients with severe liver disease. J Virol 1996, 70: 8318-8331.

Yotsuyanagi H, Hino K, Tomita E, Toyoda J, Yasuda K, Iino S: Precore and core promoter mutations, hepatitis B virus DNA levels and progressive liver injury in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2002, 37: 355-363.

Ledesma MM, Galdame O, Bouzas B, Tadey L, Livellara B, Giuliano S, Viaut M, Paz S, Fainboim H, Gadano A, Campos R, Flichman D: Characterization of the basal core promoter and precore regions in anti-HBe-positive inactive carriers of hepatitis B virus. Int J Infect Dis 2011, 15: 314-320.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of Universidad de Buenos Aires, Agencia Nacional de Promocion Cientifica y Tecnologica and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnicas, Argentina.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LB contributed to the conception and the design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis of results, writing of the manuscript and its final approval; LT contributed to the analysis of the results; SF and BB contributed to the design of the study, RC contributed to the conception and the design of the study, analysis of the results, writing the manuscript and its final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Barbini, L., Tadey, L., Fernandez, S. et al. Molecular characterization of hepatitis B virus X gene in chronic hepatitis B patients. Virol J 9, 131 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-9-131

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-9-131