Abstract

Background

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) genotypes frequency is important for the predication of response to therapy and duration of treatment. Despite variable response rates experienced in the case of Interferon (IFN) -based therapies, there was scarcity of data on HCV genotypes frequency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK).

Study Design

A total of 200 blood samples were collected from chronic HCV patients prior to the initiation of anti-viral therapy. The study population included patients from 6 districts of KPK. Active HCV infection was confirmed in case of all the patients by real time PCR. HCV genotypes were determined in each case by Type-specific PCR.

Results

The analysis revealed that out of 200 PCR positive samples; 78 (39%) were 2a, 62 (31%) were 3a, 16 (8%) were 3b, 34 (17%) were untypable while 1a, 2b and 1b were 3 (1.5%), 2 (1%) and 5 (2.5%), respectively.

Conclusion

Genotype determination is not carried out prior to therapy in KPK. Although, the abundantly prevalent types (2a and 3a) of HCV in KPK are susceptible to combination therapy, yet resistance experienced in some of the chronic HCV patients may partly be attributed to the prevalence of less prevalent resistant genotypes (1a, 1b) of HCV among the population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic HCV infection frequently progresses to liver cirrhosis and is associated with an elevated risk for development of hepatocellular carcinoma [1–3]. Though symptoms may be mild for decades, 20% of persistently infected individuals may eventually develop severe liver disease including cirrhosis and liver cancer [1]. To date at least six major genotypes of HCV, each having multiple subtypes, have been identified worldwide [2]. The various HCV genotypes are important with respect to epidemiology, vaccine development and clinical management of chronic HCV infection [3]. HCV genotype has also been linked with sustained virological response [4]. Some studies have reported that patients with type 2 and type 3 HCV infections are more likely to have a sustained response to therapy than patients with type 1 HCV infections [5]. Sustained virological response to combination therapy in patients infected with HCV-2/3 and HCV-1 genotypes are 65% and 30%, respectively [6, 7]. Therefore, HCV genotype should be determined prior to therapy.

HCV genotypes 1, 2 and 3 appear to have a worldwide distribution while subtypes 1a and 1b are the most common genotypes in the United States [4] and Europe [8–10]. The most abundant subtype in Japan is subtype 1b [11]. HCV subtypes 2a and 2b are relatively common in North America, Europe and Japan and subtype 2c is found commonly in northern Italy. HCV genotype 4 appears to be prevalent in North Africa and the Middle East [12, 13] and genotypes 5 and 6 are found in South Africa and Hong Kong, respectively [14, 15]. HCV genotypes 7, 8 and 9 have been identified only in Vietnamese patients [16] and genotypes 10 and 11 have been identified in patients from Indonesia [17]. There is disagreement about the number of genotypes into which HCV isolates should be classified and genotypes 7 through 11 should are regarded by some researchers as variants of the same group and classified as a single genotype, type 6 [18, 19].

In Pakistan, few studies have been conducted in order to figure out the geographical distribution of various HCV genotypes [13, 20, 21]. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the prevalence of various HCV genotypes is unknown. As HCV genotypes have earlier been implicated in response to therapy [4], therefore it was of prime importance to investigate the frequency distribution of HCV genotypes in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan where genotype determination prior to therapy is not common practice.

Methodology

Samples were collected from chronically infected patients with HCV. None of the patients selected for the study had started with anti-viral therapy. All the patients duly signed a proforma containing their demographics, previous history of viral infection etc. Serum was isolated and extraction of RNA was carried out with spin column based method (Roboscreen extraction kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HCV-RNA was amplified using reagents and equipment from the Cepheid (Cepheid, USA).

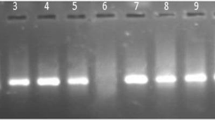

HCV genotyping was performed according to the procedure of Ohno et al., [22]. Briefly, HCV-RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using 100 U of M-MLV reverse transcriptase at 37°C for 50 minutes. Two µl of synthesized cDNA was used for subsequent PCR amplification of 470-bp region from HCV 5' noncoding region plus core region by first round PCR. The second round nested PCR was performed using Type-specific primers for genotypes 1a, 1b, 1c, 3a, 3c, 4, 2a, 2c, 3b, 5a and 6a. The final PCR product was electrophorased on a 2% agarose gel to separate type-specific amplified fragments. A 100-bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Corp., California, USA) was run in each gel as DNA size marker and the HCV genotype for each sample was determined by identifying the HCV genotype-specific PCR band.

Results

HCV genotype analysis in chronic HCV patients (age 15-60 years) of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa revealed that the most abundant genotypes/subtypes among the patients analyzed were 2a followed by subtype 3a (Table 1). Other common genotypes included the untypable type of the virus and genotype 3b. Comparatively less common genotypes were 1b, 1a and 2b (Table 1). Major risk factors associated with HCV infection were blood transfusion and dental surgery followed by major surgery (Table 2). The patient's history indicated that comparatively more patients had a history of blood transfusion in Peshawar and Mardan districts while a history of dental surgery practices was common in less developed district Bunir. Moreover, district Bunir and Peshawar had more cases of a positive family history of HCV infection as well. In the studied individuals, there were no co-infections. It was also noted that the overall prevalence of chronic HCV was more in male as compared to female (Table 2).

Discussion

HCV prevalence is alarmingly high in Pakistan and due to unsatisfactory health care conditions, the infection is spreading at a rapid pace [20]. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the health care facilities are poorly equipped with essentials for screening and sterilization, HCV has become an economic burden over a population with considerable number of people living below the poverty line.

HCV genotype determination facilitates therapeutic decisions and strategies [23, 24] and it has been reported that pathogenesis of the disease or response to therapy may vary according to the type of the virus [9, 25]. Genotype determination is not carried out prior to treatment in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the treatment strategies are solely based on qualitative or quantitative viral detection. Reasons for variable response rates in the case of different patients for both combination therapy and Pegylated IFN could therefore not properly be sorted out. We attempted to figure out HCV genotypes prevalent among the population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa so as to create awareness among the practitioners about the importance of the HCV genotype and find a preliminary answer to the resistance phenomenon experienced here.

Our study indicated that HCV genotype 2a is the most abundant followed by 3a and 2b (Table 1). The distribution of type 2 and 3 is thought to be worldwide [4] including Pakistan [10]. It has earlier been reported that HCV 2a and 3a are most susceptible to combination therapy [5] and good response rates in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa may partly be attributed to the most abundant types of HCV prevalent here. Other types of the virus including type 1a, 1b and 2b are less prevalent among the population (Table 1). Genotype 1a and 1b are prevalent in the USA [4], Europe [8, 9] and Japan [11]. These genotypes are comparatively less responsive to combination therapy [5] and the response rates in the case of Pegylated IFN have been reported to vary from 50-70% [26]. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, it is a common practice to put the non-responders on prolonged combination therapy or Pegasys. Resistance in some patients may be attributed to these less prevalent genotypes among the population.

HCV genotypes among a considerable number of chronic HCV patients (17%) could not be determined by the assay used in this study. Untypeable genotypes have earlier been reported by other studies conducted in Pakistan [23]. Sequencing of the untypeable genotypes is needed not only for academic reasons but also for future treatment directions.

This study concludes that the most abundant types of HCV among chronic HCV patients of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan are HCV type 2a, 3a and 3b. Although these abundant types are responsive to combination therapy and Pegasys, yet proper diagnostic and treatment strategies should be adopted in order to minimize the economic burden on the population and to prevent people from an extra stress of undergoing successive therapies.

References

Alter MJ, Margolis HS, Krawczynski K, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, Hu YP, Miller JK, Gerber MA, Sampliner RE: The natural history of community-acquired hepatitis C in the United States. The sentinel counties chronic non-a, non-b hepatitis study team. The New England journal of medicine 1992, 327: 1899-1905. 10.1056/NEJM199212313272702

Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS: Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science New York NY 1998, 282: 103-107.

Saito IT, Miyamura A, Ohbayashi H, Harada T, Katayama S, Kikuchi Y, Watanabe S, Koi M, Ohta Y: Hepatitis C Virus infection is associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1990, 87: 6547-6549. 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6547

Zein NN, Rakela J, Krawitt EL, Reddy KR, Tominaga T, Persing DH: Hepatitis C virus genotypes in the United States: epidemiology, pathogenicity, and response to interferon therapy. Ann Intern Med 1996, 125: 634-639.

Dusheiko GH. Schmilovitz D, Brown F, McOmish P, Yap L, Simmonds P: Hepatitis C virus genotypes. An investigation of type-specific differences in geographic origin and disease. Hepatology 1996, 19: 13-18.

McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Lee WM, Rustgi VK, Goodman ZD: Interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med 1998, 339: 1485-1492. 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101

Poynard TP, Marcellin SS, Lee C, Niederau GS, Minuk G, Ideo V, Bain : Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. Lancet 1998, 352: 1426-1432. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07124-4

McOmish FP, Yap IL, Dow BC, Follett EAC, Seed C, Keller AJ, Cobain TJ, Krusius T, Kolho E, Naukkarinen R, Lin C, Lai C, Leong S, Medgyesi GA, Heéjjas M, Kiyokawa H, Fukada K, Cuypers T, Saeed AA, Al-Rasheed AM, Lin M, Simmonds P: Geographic distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in blood donors: an international collaborative survey. J Clin Microbiol 1994, 32: 884-92.

Dusheiko GJ, Thomas H: Ribavirin treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C: results of a placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol 1994,25(Suppl 5):591-598.

Nousbaum JB, Pol S, Nalpas B, Landais P, Berthelot P, Brechot C: The Collaborative Study Group: Hepatitis C virus type 1b (II) infection in France and Italy. Ann Intern Med 1995, 122: 161-168.

Takada NS, Takase S, Takada A: Differences in the hepatitis C virus genotypes in different countries. J Hepatol 1993, 17: 277-283. 10.1016/S0168-8278(05)80205-3

Abdulkarim AS, Zein NN, Germer JJ, Kolbert CP, Kabbani L, Krajnik KL, Hola A, Agha MN, Tourogman M, Persing DH: Hepatitis C virus genotypes and hepatitis G virus in hemodialysis patients from Syria: identification of two novel hepatitis C virus subtypes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998, 59: 571-576.

Chamberlain RW, Adams N, Saeed AA, Simmonds P, Elliot RM: Complete nucleotide sequence of a type 4 hepatitis C virus variant, the predominantgenotype in the Middle East. J Gen Virol 1994, 78: 1341-1347.

Simmonds P, Holmes EC, Cha TA, Chan SW, McOmish F, Irvine B, Beall E, Yap PL, Kolberg J, Urdea MS: Classification of hepatitis C virus into six major genotypes and a series of subtypes by phylogenetic analysis of the NS-5 region. J Gen Virol 1993, 74: 2391-9. 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2391

Cha TA, Kolberg J, Irvine B, Stempien M, Beall E, Yano M, Choo QL, Houghton M, Kuo G, Han JH, Urdea MS: Use of a signature nucleotide sequence of hepatitis C virus for detection of viral RNA in human serum and plasma. J Clin Microbiol 1992, 29: 2528-2534.

Tokita HS, Shrestha M, Okamoto H, Sakamoto S, Horikita M, Iizuka H, Shrestha S, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M: Hepatitis C virus variants from Nepal with novel genotypes and their classification into the third major group. J Gen Virol 1994, 75: 931-936. 10.1099/0022-1317-75-4-931

Tokita HH, Okamoto H, Iizuka H, Kishimoto F, Tsuda L, Lesmana A, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M: Hepatitis C virus variants from Jakarta, Indonesia classifiable into novel genotypes in the second (2e and 2f), tenth (10a) and eleventh (11a) genetic groups. J Gen Virol 1996, 77: 293-301. 10.1099/0022-1317-77-2-293

DeLamballerie X, Charrel RN, Attoui H, DeMicco P: Classification of hepatitis C virus variants in six major types based on analysis of the envelope 1 and nonstructural 5B genome regions and complete polyprotein sequences. J Gen Virol 1997, 78: 45-51.

Tokita HH, Okamoto H, Iizuka J, Kishimoto F, Tsuda Y, Mayumi M: The entire nucleotide sequences of three hepatitis C virus isolates in genetic groups7–9and comparison with those in the other eight genetic groups. J Gen Virol 1998, 79: 1847-1857.

Shah HA, Jafri WS, Malik I, Prescott L, Simmonds P: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotypes and chronic liver disease in Pakistan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997, 12: 758-761. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00366.x

Idrees M: Common genotypes of hepatitis C virus present in Pakistan. Pak J Med Res 2001,40(Suppl 2):46-49.

Ohno T, Mizokami M, Wu R, Saleh M, Ohba K, Orito E, Mukaide M, Williams R, Lau J: New hepatitis C virus genotyping system that allows for identification of HCV genotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b, 4, 5a, and 6a. J Clin Microbiol 1997, 35: 201-207.

Poynard T, Bedossa P, Chevallier M, Matturin P, Lemonnier C, Trepo C, Couzigou P, Payen JL, Sajus M, Costa JM, Vidaud M, Chaput JC, the Multicenter Study Group: A comparison of three Interferon alpha 2b regimens for long terms treatment of chronic non A, non B hepatitis. N Engl J Med 1995, 332: 1457-62. 10.1056/NEJM199506013322201

Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Rustgi V, Hoefs J, Gordon SC, Trepo C, Shiffman ML, Zeuzem S, Craxì A, Ling MH, Alvrecht J: Interferon alpha-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin for the treatment of relapse of chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 1998, 339: 1493-1499. 10.1056/NEJM199811193392102

McHutchison JG, Poynard T, Davis GL, Esteban-Mur R, Harvey J, Ling M, Cort S, Fraud JJ, Albrecht J, Dienstag J: Evaluation of hepatic HCV RNA before and after treatment with interferon alfa 2b or combined with ribavirin in chronic hepatitis. Hepatology 1990,30(Suppl 2):363A.

Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan J, Balan TR, Diago V, Marcellin M, Ramadori P, Bodenheimer G, Bernstein HJ, Rizzetto D, Pockros S, Lin PJA, Ackrill AM: Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C. a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med 2004, 140: 346-55.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SA (research scholar) carried out sampling and experimental work, BA supervised the research work conducted by SA and designed the experimental work and manuscript preparation with the help of IA (Co-supervisor). SA helped in manuscript reviewing and corrections prepared by research scholar. The final manuscript is approved by all of the authors after reviewing it critically.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, S., Ali, I., Azam, S. et al. Frequency distribution of HCV genotypes among chronic hepatitis C patients of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Virol J 8, 193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-193

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-8-193