Abstract

Control of transcription is crucial for correct gene expression and orderly development. For many years, bacteriophage T4 has provided a simple model system to investigate mechanisms that regulate this process. Development of T4 requires the transcription of early, middle and late RNAs. Because T4 does not encode its own RNA polymerase, it must redirect the polymerase of its host, E. coli, to the correct class of genes at the correct time. T4 accomplishes this through the action of phage-encoded factors. Here I review recent studies investigating the transcription of T4 prereplicative genes, which are expressed as early and middle transcripts. Early RNAs are generated immediately after infection from T4 promoters that contain excellent recognition sequences for host polymerase. Consequently, the early promoters compete extremely well with host promoters for the available polymerase. T4 early promoter activity is further enhanced by the action of the T4 Alt protein, a component of the phage head that is injected into E. coli along with the phage DNA. Alt modifies Arg265 on one of the two α subunits of RNA polymerase. Although work with host promoters predicts that this modification should decrease promoter activity, transcription from some T4 early promoters increases when RNA polymerase is modified by Alt. Transcription of T4 middle genes begins about 1 minute after infection and proceeds by two pathways: 1) extension of early transcripts into downstream middle genes and 2) activation of T4 middle promoters through a process called sigma appropriation. In this activation, the T4 co-activator AsiA binds to Region 4 of σ70, the specificity subunit of RNA polymerase. This binding dramatically remodels this portion of σ70, which then allows the T4 activator MotA to also interact with σ70. In addition, AsiA restructuring of σ70 prevents Region 4 from forming its normal contacts with the -35 region of promoter DNA, which in turn allows MotA to interact with its DNA binding site, a MotA box, centered at the -30 region of middle promoter DNA. T4 sigma appropriation reveals how a specific domain within RNA polymerase can be remolded and then exploited to alter promoter specificity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Expression of the T4 genome is a highly regulated and elegant process that begins immediately after infection of the host. Major control of this expression occurs at the level of transcription. T4 does not encode its own RNA polymerase (RNAP), but instead encodes multiple factors, which serve to change the specificity of polymerase as infection proceeds. These changes correlate with the temporal regulation of three classes of transcription: early, middle, and late. Early and middle RNA is detected prereplicatively [previously reviewed in [1–6]], while late transcription is concurrent with T4 replication and discussed in another chapter. T4 early transcripts are generated from early promoters (Pe), which are active immediately after infection. Early RNA is detected even in the presence of chloramphenicol, an antibiotic that prevents protein synthesis. In contrast, T4 middle transcripts are generated about 1 minute after infection at 37°C and require phage protein synthesis. Middle RNA is synthesized in two ways: 1) activation of middle promoters (Pm) and 2) extension of Pe transcripts from early genes into downstream middle genes.

This review focuses on investigations of T4 early and middle transcription since those detailed in the last T4 book [1, 5]. At the time of that publication, early and middle transcripts had been extensively characterized, but the mechanisms underlying their synthesis were just emerging. In particular, in vitro experiments had just demonstrated that activation of middle promoters requires a T4-modified RNAP and the T4 activator MotA [7, 8]. Subsequent work has identified the needed RNAP modification as the tight binding of a 10 kDa protein, AsiA, to the σ70 subunit of RNAP [9–13]. In addition, a wealth of structural and biochemical information about E. coli RNAP [reviewed in [14–16]], MotA, and AsiA [reviewed in [2]] has now become available. As detailed below, we now have a much more mechanistic understanding of the process of prereplicative T4 transcription. To understand this process, we first start with a review of the host transcriptional machinery and RNAP.

The E. coli transcriptional machinery

E. coli RNAP holoenzyme, like all bacterial RNAPs, is composed of a core of subunits (β, β',α1, α2, and ω), which contains the active site for RNA synthesis, and a specificity factor, σ, which recognizes promoters within the DNA and sets the start site for transcription. The primary σ, σ70 in E. coli, is used during exponential growth; alternate σ factors direct transcription of genes needed during different growth conditions or times of stress [reviewed in [17–19]]. Sequence/function analyses of hundreds of σ factors have identified various regions and subregions of conservation. Most σ factors share similarity in Regions 2-4, the central through C-terminal portion of the protein, while primary σ factors also have a related N-terminal portion, Region 1.

Recent structural information, together with previous and ongoing biochemical and genetic work [reviewed in [14, 15, 20, 21]], has resulted in a biomolecular understanding of RNAP function and the process of transcription. Structures of holoenzyme, core, and portions of the primary σ of thermophilic bacteria with and without DNA [15, 16, 22–28], and structures of regions of E. coli σ70 alone [29] and in a complex with other proteins [26, 30] are now available. This work indicates that the interface between σ70 and core within the RNAP holoenzyme is extensive (Figure 1). It includes contact between a portion of σ Region 2 and a coiled/coil domain composed of β, β', an interaction of σ70 Region 1.1 within the "jaws" in the downstream DNA channel (where DNA downstream of the transcription start site will be located when RNAP binds the promoter), and an interaction between σ70 Region 4 and a portion of the β subunit called the β-flap.

RNAP holoenzyme and the interaction of RNAP with σ70-dependent promoters. Structure-based cartoons (left to right) depict RNAP holoenzyme, RPc (closed complex), RPo (open complex), and EC (elongating complex) with σ70 in yellow, core (β,β',α2, and ω) in turquoise, DNA in magenta, and RNA in purple. In holoenzyme, the positions of σ70 Regions 1.1, 2, 3, and 4, the α-CTDs, the β-flap, and the β,β' jaws are identified. In RPc, contact can be made between RNAP and promoter dsDNA elements: two UP elements with each of the α-CTDs, the -35 element with σ70 Region 4, TGn (positions -15 to -13) with σ70 Region 3, and positions -12/-11 of the -10 element with σ70 Region 2. σ70 Region 1.1 lies in the downstream DNA channel formed by portions of β and β' and the β',β' jaws are open. In RPo, unwinding of the DNA and conformational changes within RNAP result in a sharp bend of the DNA into the active site with the formation of the transcription bubble surrounding the start of transcription, the interaction of σ70 Region 2 with nontemplate ssDNA in the -10 element, movement of Region 1.1 from the downstream DNA channel, and contact between the downstream DNA and the β' clamp. In EC, σ70 and the promoter DNA have been released. The newly synthesized RNA remains annealed to the DNA template in the RNA/DNA hybrid as the previously synthesized RNA is extruded through the RNA exit channel past the β-flap.

For transcription to begin, portions of RNAP must first recognize and bind to double-stranded (ds) DNA recognition elements present within promoter DNA (Figure 1) [reviewed in [20]]. Each of the C-terminal domains of the α subunits (α-CTDs) can interact with an UP element, A/T rich sequences present between positions -40 and -60. Portions of σ70, when present in RNAP, can interact with three different dsDNA elements. A helix-turn-helix, DNA binding motif in σ70 Region 4 can bind to the -35 element, σ70 Region 3 can bind to a -15TGn-13 sequence (TGn), and σ70 subregion 2.4 can bind to positions -12/-11 of a -10 element. Recognition of the -35 element also requires contact between residues in σ70 Region 4 and the β-flap in order to position σ70 correctly for simultaneous contact of the -35 and the downstream elements. Typically, a promoter only needs to contain two of the three σ70-dependent elements for activity; thus, E. coli promoters can be loosely classified as -35/-10 (the major class), TGn/-10 (also called extended -10), or -35/TGn [reviewed in [20]].

The initial binding of RNAP to the dsDNA promoter elements usually results in an unstable, "closed" complex (RPc) (Figure 1). Creation of the stable, "open" complex (RPo) requires bending and unwinding of the DNA [31] and major conformational changes (isomerization) of the polymerase (Figure 1) [[32, 33]; reviewed in [20]]. In RPo the unwinding of the DNA creates the transcription bubble from -11 to ~+3, exposing the single-stranded (ss) DNA template for transcription. Addition of ribonucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) then results in the synthesis of RNA, which remains as a DNA/RNA hybrid for about 8-9 bp. Generation of longer RNA initiates extrusion of the RNA through the RNA exit channel formed by portions of β and β' within core. Since this channel includes the σ70-bound β-flap, it is thought that the passage of the RNA through the channel helps to release σ from core, facilitating promoter clearance. The resulting elongation complex, EC, contains core polymerase, the DNA template, and the synthesized RNA (Figure 1) [reviewed in [34]]. The EC moves rapidly along the DNA at about 50 nt/sec, although the complex can pause, depending on the sequence [35]. Termination of transcription occurs either at an intrinsic termination signal, a stem-loop (hairpin) structure followed by a U-rich sequence, or a Rho-dependent termination signal [reviewed in [36, 37]]. The formation of the RNA hairpin by an intrinsic terminator sequence may facilitate termination by destabilizing the RNA/DNA hybrid. Rho-dependent termination is mediated through the interaction of Rho protein with a rut site (Rho utilization sequence), an unstructured, sometimes C-rich sequence that lies upstream of the termination site. After binding to the RNA, Rho uses ATP hydrolysis to translocate along the RNA, catching up with the EC at a pause site. Exactly how Rho disassociates a paused complex is not yet fully understood; the DNA:RNA helicase activity of Rho may provide a force to "push" RNAP off the DNA. Rho alone is sufficient for termination at some Rho-dependent termination sites. However, at other sites the termination process also needs the auxiliary E. coli proteins NusA and/or NusG [reviewed in [36].

When present in intergenic regions, rut sites are readily available to interact with Rho. However, when present in protein-coding regions, these sites can be masked by translating ribosomes. In this case, Rho termination is not observed unless the upstream gene is not translated, for example, when a mutation has generated a nonsense codon. In such a case, Rho-dependent termination can prevent transcription from extending into the downstream gene. Thus, in this situation, which is called polarity [38], expression of both the upstream mutated gene and the downstream gene is prevented.

T4 early transcription

Early promoters

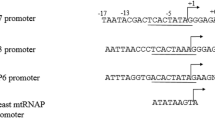

T4 only infects exponentially growing E. coli, and transcription of T4 early genes begins immediately after infection. Thus, for an efficient infection, the phage must rapidly redirect the σ70-associated RNAP, which is actively engaged in transcription of the host genome, to the T4 early promoters. This immediate takeover is successful in part because most T4 early promoters contain excellent matches to the σ70-RNAP recognition elements (-35, TGn, and -10 elements) and to the α-CTD UP elements (Figure 2; for lists of T4 early promoter sequences, see [4, 5]). However, sequence alignments of T4 early promoters reveal additional regions of consensus, suggesting that they contain other bits of information that can optimize the interaction of host RNAP with the promoter elements. Consequently, unlike most host promoters that belong to the -35/-10, TGn/-10 or -35/TGn class, T4 early promoters can be described as "über" UP/-35/TGn/-10 promoters. Indeed, most T4 early promoters compete extremely well with the host promoters for the available RNAP [39] and are similar to other very strong phage promoters, such as T7 PA1 and λ PL.

Comparison of E. coli host, T4 early, and T4 middle promoter sequences. Top, Sequences and positions of host promoter recognition elements for σ70-RNAP (UP, -35, TGn, -10) are shown [20, 150]. Below, similar consensus sequences found in T4 early [4] and middle [91] promoters are in black and differences are in red; the MotA box consensus sequence in T4 middle promoters is in green. Spacer lengths between the TGn elements and the -35 elements (host and T4 early) or the MotA box are indicated. W = A or T; R = A or G; Y = C or T, n = any nucleotide; an uppercase letter represents a more highly conserved base.

The T4 Alt protein

Besides the sheer strength of its early promoters, T4 has another strategy, the Alt protein, to establish transcriptional dominance [[40–43], reviewed in [1, 4]]. Alt, a mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase, ADP-ribosylates a specific residue, Arg265, on one of the two α subunits of RNAP. In addition, Alt modifies a fraction of other host proteins, including the other RNAP subunits and host proteins involved in translation and cell metabolism. Alt is an internal phage head protein that is injected with the phage DNA. Consequently, Alt modification occurs immediately after infection and does not require phage protein synthesis. Each α subunit is distinct (one α interacts with β while the other interacts with β') and Alt modification is thought to specifically target a particular α, although which particular α is not known.

What is the purpose of Alt modification? The major Alt target, α Arg265, has been shown to be crucial for the interaction of an α-CTD with a promoter UP element [44–46] and with some host activators, including c-AMP receptor protein (CRP), a global regulator of E. coli [46, 47]. Thus, an obvious hypothesis is that Alt simply impairs host promoters that either need these activators or are enhanced by α-CTD/UP element interaction. However, overexpression of Alt from a plasmid does not affect E. coli growth [40], and general transcription of E. coli DNA in vitro is not impaired when using Alt-modified RNAP [48]. Instead, it appears that Alt-modification is helpful because it increases the activity of certain T4 early promoters. This 2-fold enhancement of activity has been observed both in vivo [40, 49] and in vitro [48]. How Alt-modification stimulates particular early promoters is not known, but it is clear that it is not simply due to their general strength. Other strong promoters, such as Ptac, T7 PA1 and PA2, T5 P207, and even some of the T4 early promoters, are unaffected when using Alt-modified RNAP [49]. Alt-mediated stimulation of a promoter is also not dependent on specific σ70-dependent elements (-35, TGn, and -10 elements); some promoters with identical sequences in these regions are stimulated by Alt while others are not [49]. A comprehensive mutational analysis of the T4 early promoter P8.1 and Ptac reveals that there is not a single, specific promoter position(s) responsible for the Alt effect. This result suggests that the mechanism of Alt stimulation may involve cross-talk between RNAP and more than one promoter region [50] or that ADP-ribosylation of α Arg265 is a secondary, less significant activity of Alt and additional work on the importance of this injected enzyme is needed.

Continuing early strategies for T4 domination

Because T4 promoters are so efficient at out-competing those of the host, a burst of immediate early transcription occurs within the first minute of infection. From this transcription follows a wave of early products that continue the phage takeover of the host transcriptional machinery. One such product is the T4 Alc protein, a transcription terminator that is specific for dC-containing DNA, that is, DNA that contains unmodified cytosines. Consequently, Alc terminates transcription from host DNA without affecting transcription from T4 DNA, whose cytosines are hydroxymethylated and glucosylated [[51, 52]; reviewed in [1, 4]]. Alc directs RNAP to terminate at multiple, frequent, and discrete sites along dC-containing DNA. The mechanism of Alc is not known. Unlike other terminating factors, Alc does not appear to interact with either RNA or DNA, and decreasing the rate of RNA synthesis or RNAP pausing near an Alc termination site actually impairs Alc termination [51]. Mutations within an N-terminal region of the β subunit of RNAP, a region that is not essential for E. coli (dispensable region I), prevent Alc -mediated termination, suggesting that an interaction site for Alc may reside in this region [52].

T4 also encodes two other ADP-ribosylating enzymes, ModA and ModB, as early products. Like Alt, ModA modifies Arg265 of RNAP α [[53, 48]; reviewed in [1, 4]]. However, unlike Alt, ModA almost exclusively targets the RNAP α subunits. In addition, ModA modifies both α subunits so there is no asymmetry to ModA modification. Synthesis of ModA is highly toxic to E. coli. In vitro, ModA-modified RNAP is unable to interact with UP elements or to interact with CRP [cited in [40]] and is less active than unmodified RNAP when using either E. coli or T4 DNA [48]. Thus, it has been suggested that ModA helps to diminish both host and T4 early promoter activity, reprogramming the transcriptional machinery for the coming wave of middle transcription [48]. However, a deletion of the modA gene does not affect the rapid decrease in early transcription or the decrease in the synthesis of early gene products, which begins about 3 minutes post-infection [54]. This result suggests that the phage employs other as yet unknown strategies to stop transcription from early promoters. ModB, the other early ADP-ribosylating enzyme, targets host translation factors, the ribosomal protein S30 and trigger factor, which presumably helps to facilitate T4 translation [43].

Finally, many of the early transcripts include genes of unknown function and come from regions of the T4 genome that are not essential for infection of wild type (wt) E. coli under normal laboratory conditions. Presumably, these genes encode phage factors that are useful under specific growth conditions or in certain strains. Whether any of these gene products aid T4 in its takeover of the host transcriptional machinery is not known.

The switch to middle transcription

Within a minute of infection at 37°C, some of the T4 early products mediate the transition from early to middle gene expression. As detailed below, the MotA activator and AsiA co-activator are important partners in this transition, since they direct RNAP to transcribe from middle promoters. In addition, the ComC-α protein, described later, may also have a role in the extension of early RNAs into downstream middle genes or the stability of such transcripts once they are formed.

As middle transcription begins, certain early RNAs decay rapidly after their initial burst of transcription. This arises from the activity of the early gene product RegB, an endoribonuclease, which specifically targets some T4 early mRNAs. For the mRNAs of MotA and RegB itself, a RegB cleavage site lies within the Shine-Dalgarno sequence; for ComC-α mRNA, the site is within AU-rich sequences upstream and downstream of this sequence [55]. The mechanism by which RegB recognizes and chooses the specific cleavage site is not yet known.

The onset of T4 middle transcription also finishes the process of eliminating host transcription by simply removing the host DNA template for RNAP. T4-encoded nucleases, primarily EndoII encoded by denA and EndoIV encoded by denB, selectively degrade the dC-containing host DNA ([56, 57] and references therein). Thus, a few minutes after infection, there is essentially no host DNA to transcribe.

Transcription of middle genes from T4 middle promoters

Middle promoters

Middle genes primarily encode proteins needed for replication, recombination, and nucleotide metabolism; various T4-encoded tRNAs; and transcription factors that program the switch from middle to late promoter activation. Middle RNAs arise by 2 pathways: extension of early transcription into middle genes (discussed later) and the activation of T4 middle promoters by a process called σ appropriation [2]). To date, nearly 60 middle promoters have been identified (Table 1). Unlike early promoters, T4 middle promoters contain a host element, the σ70-dependent -10 sequence, and a phage element, a MotA box, which is centered at -30 and replaces the σ70-dependent -35 element present in T4 early promoters and most host promoters (Figure 2). In addition, about half of the middle promoters also contain TGn, the extended -10 sequence. Activation of the phage middle promoters requires the concerted effort of two T4 early products, AsiA and MotA.

AsiA, the co-activator of T4 middle transcription

AsiA (A udrey S tevens i nhibitor or a nti-s igma i nhibitor) is a small protein of 90 residues. It was originally identified as a 10 kDa protein that binds very tightly to the σ70 subunit of RNAP [11, 58, 59] with a ratio of 1:1 [60]. Later work indicated that a monomer of AsiA binds to C-terminal portions of σ70, Regions 4.1 and 4.2 [26, 60–70]. In solution, AsiA is a homodimer whose self-interaction face is composed of mostly hydrophobic residues within the N-terminal half of the protein [65, 71]. A similar face of AsiA interacts with σ70 [26], suggesting that upon binding to σ70, a monomer of AsiA in the homodimer simply replaces its partner for σ70. Curiously, the AsiA structure also contains a helix-turn-helix motif (residues 30 to 59), suggesting the possibility of an interaction between AsiA and DNA [71]. However, as yet, no such interaction has been detected.

Multiple contacts make up the interaction between AsiA and σ70 Region 4 (Figure 3A). The NMR structure (Figure 3B, right) reveals that 18 residues present in three α helices within the N-terminal half of AsiA (residues 10 to 42) contact 17 residues of σ70 [26]. Biochemical analyses have confirmed that AsiA residues E10, V14, I17, L18, K20, F21, F36, and I40, which contact σ70 Region 4 in the structure, are indeed important for the AsiA/σ70 interaction and/or for AsiA transcriptional function in vitro [72–74]. Of all of these residues, I17 appears to be the most important, and thus, has been termed "the linchpin" of the AsiA/σ70 Region 4 interaction [74]. A mutant AsiA missing the C-terminal 17 residues is as toxic as the full length protein when expressed in vivo [72, 75], and even a mutant missing the C-terminal 44 residues is still able to interact with σ70 Region 4 and to co-activate transcription weakly [72]. These results are consistent with the idea that only the N-terminal half of AsiA is absolutely required to form a functional AsiA/σ70 complex. Together, the structural and biochemical work indicate that there is an extensive interface between the N-terminal half of AsiA and σ70 Region 4, consistent with the early finding that AsiA copurifies with σ70 until urea is added to dissociate the complex [76].

Interaction of σ70region 4 with -35 element DNA, the β-flap, AsiA and MotA. A) Sequence of σ70 Region 4 (residues 540-613) with subregions 4.1 and 4.2; the α helices H1 through H5 with a turn (T) between H3 and H4 are shown. Residues of σ70 that interact with the -35 element [25] are colored in magenta. Residues that interact with AsiA [26] or the region that interacts with MotA [97, 104] is indicated. B) Structures showing the interaction of T. aquaticus σ Region 4 with -35 element DNA [25] (left, accession # 1KU7) and interaction of σ70 Region 4 with AsiA [26] (right, accession # 1TLH). σ, yellow; DNA, magenta; AsiA, N-terminal half in black, C-terminal half in gray. On the left, the portions of σ that interact with the β-flap (σ residues in and near H1, H2, and H5) are circled in turquoise; on the right, H5, the far C-terminal region of σ70 that interacts with MotA, is in the green square. C) Structures showing the interaction of T. thermophilus σ H5 with the β-flap tip [22] (left, accession # 1IW7) and the structure of MotANTD [94] (right, accession # 1I1S) are shown. On the β-flap (left) and MotANTD (right) structures, hydrophobic residues (L, I, V, or F) and basic residues (K or R) are colored in gray or blue, respectively. The interaction site at the β-flap tip is a hydrophobic hook, while the structure in MotANTD is a hydrophobic cleft.

The σ70 face of the AsiA/σ70 complex includes residues in Regions 4.1 and 4.2 that normally contact the -35 DNA element or the β-flap of core [26] (Figure 3). Mutations within Region 4.1 or Region 4.2, which are at or near the AsiA contact sites in σ70, impair or eliminate AsiA function [77–79], providing biochemical evidence for these interactions. The structure of the AsiA/σ70 Region 4 complex also reveals that AsiA binding dramatically changes the conformation of σ70 Region 4, converting the DNA binding helix-turn-helix (Figure 3B, left) into one continuous helix (Figure 3B, right). Such a conformation would be unable to retain the typical σ70 contacts with either the -35 DNA or with the β-flap. Thus, the association of AsiA with σ70 should inhibit the binding of RNAP with promoters that depend on recognition of a -35 element. Indeed, early observations showed that AsiA functions as a transcriptional inhibitor at most promoters in vitro [9, 10], blocking RPc formation [60], but TGn/-10 promoters, which are independent of a RNAP/-35 element contact, are immune to AsiA [62, 66, 80]. However, this result is dependent on the buffer conditions. In the presence of glutamate, a physiologically relevant anion that is known to facilitate protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions [81, 82], extended incubations of AsiA-associated RNAP with -10/-35 and -35/TGn promoters eventually result in the formation of transcriptionally competent, open complexes that contain AsiA [72, 83]. Under these conditions, AsiA inhibition works by significantly slowing the rate of RPo formation [83]. However, the formation of these complexes still relies on DNA recognition elements other than the -35 element (UP, TGn, and -10 elements), again demonstrating that AsiA specifically targets the interaction of RNAP with the -35 DNA.

Because AsiA strongly inhibits transcription from -35/-10 and -35/TGn promoters, expression of plasmid-encoded AsiA is highly toxic in E. coli. Thus, during infection, AsiA may serve to significantly inhibit host transcription. Although it might be reasonable to suppose that AsiA performs the same role at T4 early promoters, this is not the case. The shut-off of early transcription, which occurs a few minutes after infection, is still observed in a T4 asiA- infection [54], and early promoters are only modestly affected by AsiA in vitro [84]. This immunity to AsiA is probably due to the multiple RNAP recognition elements present in T4 early promoters (Figure 2). Thus, AsiA inhibition does not significantly contribute to the early to middle promoter transition. AsiA also does not help to facilitate the replacement of σ70 by the T4-encoded late σ factor, which is needed for T4 late promoter activity [85], indicating that AsiA is not involved in the middle to late promoter transition.

Although AsiA was originally designated as an "anti-sigma" factor and is still frequently referred to as such, it is important to note that it behaves quite differently from classic anti-sigma factors. Unlike these factors, its binding to σ70 does not prevent the σ70/core interaction; it does not sequester σ70. Instead it functions as a member of the RNAP holoenzyme. Consequently, AsiA is more correctly designated as a co-activator rather than an anti-sigma factor, and its primary role appears to be in activation rather than inhibition.

MotA, the transcriptional activator for middle promoters

The T4 motA (m odifier o f t ranscription) gene was first identified from a genetic selection developed to isolate mutations in T4 that increase the synthesis of the early gene product rIIA [86]. In fact, expression of several early genes increase in the T4 motA- infection, presumably because of a delay in the shift from early to middle transcription [87]. MotA is a basic protein of 211 amino acids, which is expressed as an early product [88]. The MotA mRNA is cleaved within its Shine-Dalgarno sequence by the T4 nuclease, RegB. Consequently, the burst of MotA protein synthesis, which occurs within the first couple minutes of infection [55], must be sufficient for all the subsequent MotA-dependent transcription.

MotA binds to a DNA recognition element, the MotA box, to activate transcription in the presence of AsiA-associated RNAP [7, 8, 11–13, 89, 90]. A MotA box consensus sequence of 5'(a/t)(a/t)(a/t)TGCTTtA3' [91] has been derived from 58 T4 middle promoters (Pm) (Table 1). This sequence is positioned 12 bp +/- 1 from the σ70-dependent -10 element,-12TAtaaT-7 (Figure 2). MotA functions as a monomer [92–94] with two distinct domains [95]. The N-terminal half of the protein, MotANTD contains the trans-activation function [96–98]. The structure of this region shows five α-helices, with helices 1, 3, 4, and 5 packing around the central helix 2 [93]. The C-terminal half, MotACTD, binds MotA box DNA [97] and consists of a saddle-shaped, 'double wing' motif, three α-helices interspersed with six β-strands [94]. As information about MotA-dependent activation has emerged, it has become apparent that MotA differs from other activators of bacterial RNAP in several important aspects. The unique aspects of MotA are discussed below.

1) MotA tolerates deviations within the MotA box consensus sequence

Early work [[3, 99]; reviewed in [1]] identified a highly conserved MotA box sequence of (a/t)(a/t)TGCTT(t/c)a with an invariant center CTT based on more than twenty T4 middle promoters. However, subsequent mutational analyses revealed that most single bp changes within the consensus sequence, even within the center CTT, are well-tolerated for MotA binding and activation in vitro [100]. Furthermore, several active middle promoters have been identified whose MotA boxes deviate significantly from the consensus, confirming that MotA is indeed tolerant of bp changes in vivo [91, 100–102].

An examination of the recognized base determinants within the MotA box has revealed that MotA senses minor groove moieties at positions -32 and -33 and major groove determinants at positions -28 and -29 [103]. (For this work, the MotA box was located at positions -35 to -26, its position when it is present 13 bp upstream of the -10 element.) In particular, the 5-Me on -29 T contributes to MotA binding. However, despite its high conservation, there seems to be little base recognition of -31 G:C, -30 C:G at the center of the MotA box. In wt T4 DNA, each cytosine in this sequence is modified by the presence of a hydroxymethylated, glucosylated moiety at cytosine position 5. This modification places a large, bulky group within the major groove, making it highly unlikely that MotA could contact a major groove base determinant at these positions. In addition, MotA binds and activates transcription using unmodified DNA; thus, the modification itself cannot be required for function. However, for two specific sequences, DNA modification does seem to affect MotA activity. One case is the middle promoter upstream of gene 46, P46. The MotA box within P46 contains the unusual center sequence ACTT rather than the consensus GCTT. MotA binds a MotA box with the ACTT sequence poorly, and MotA activation of P46 in vitro using wt T4 DNA is significantly better than that observed with unmodified DNA [100]. These results suggest that DNA modification may be needed for full activity of the ACTT MotA box motif. On the other hand, when using unmodified DNA in vitro, MotA binds a MotA box with a center sequence of GATT nearly as well as one with the consensus GCTT sequence, and a promoter with the GATT motif is fully activated by MotA in vitro. However, several potential T4 middle promoter sequences with a GATT MotA box and an excellent σ70-dependent -10 element are present within the T4 genome, but these promoters are not active [100]. This result suggests that the cytosine modification opposite the G somehow "silences" GATT middle promoter sequences.

2) MotA is not a strong DNA-binding protein

In contrast to many other well-characterized activators of E. coli RNAP, MotA has a high apparent dissociation constant for its binding site (100 - 600 nM [92, 103, 104]), and a large excess of MotA relative to DNA is needed to detect a MotA/DNA complex in a gel retardation assay or to detect protein protection of the DNA in footprinting assays [90]. In contrast, stoichiometric levels of MotA are sufficient for transcription in vitro [90]. These results are inconsistent with the idea that the tight binding of MotA to a middle promoter recruits AsiA-associated RNAP for transcription. In fact, in nuclease protection assays, MotA binding to the MotA box of a middle promoter is much stronger in the presence of AsiA and RNAP than with MotA alone [89, 90]. Furthermore, in contrast to the sequence deviations permitted within the MotA box, nearly all middle promoters have a stringent requirement for an excellent match to the σ70-dependent -10 element [91, 100, 101]. This observation suggests that the interaction of σ70 Region 2.4 with its cognate -10 sequence contributes at least as much as MotA binding to the MotA box in the establishment of a stable RNAP/MotA/AsiA/Pm complex.

3) The MotA binding site on σ70 is unique among previously characterized activators of RNAP

Like many other characterized activators, MotA interacts with σ70 residues within Region 4 to activate transcription. However, other activators target basic σ70 residues from 593 to 603 within Region 4.2 that are immediately C-terminal to residues that interact specifically with the -35 element DNA [27, 105–112] [Figure 3A; reviewed in [113]]. In contrast, the interaction site for MotA is a hydrophobic/acidic helix (H5) located at the far C-terminus of σ70 (Figure 3A). MotANTD interacts with this region in vitro and mutations within σ70 H5 impair both MotA binding to σ70 and MotA-dependent transcription [77, 97, 104]. In addition, a mutation within H5 restores infectivity of a T4 motA- phage in a particular strain of E. coli, TabG [114], which does not support T4 motA- growth [115].

Recent structural and biochemical work has indicated that a basic/hydrophobic cleft within MotANTD contains the molecular face that interacts with σ70 H5 (Figure 3C, right). Mutation of MotA residues K3, K28, or Q76, which lie in this cleft, impair the ability of MotA to interact with σ70 H5 and to activate transcription, and render the protein incapable of complementing a T4 motA- phage for growth [104]. Interestingly, substitutions of MotA residues D30, F31, and D67, which lie on another exposed surface outside of this cleft, also have deleterious effects on the interaction with σ70, transcription, and/or phage viability [98, 104]. These residues are contained within a hydrophobic, acidic patch, which may also be involved in MotA activation or another unidentified function of MotA.

The process of sigma appropriation

The mechanism of MotA-dependent activation occurs through a novel process, called sigma appropriation [reviewed in [2]]. Insight into this process began with the finding that some middle promoters function in vitro with RNAP alone. The middle promoter PuvsX, which is positioned upstream of the T4 recombination gene uvsX, is such a promoter [13]. This promoter is active because it has UP elements and a perfect -10 element to compensate for its weak homology to a σ70 -35 sequence. (It should be noted that significant activity of PuvsX and other middle promoters in the absence of MotA/AsiA is only seen when using unmodified DNA, because the modification present in T4 DNA obscures needed major grove contacts for RNAP.) Using unmodified PuvsX DNA, it has been possible to investigate how the presence of MotA and AsiA alone and together affect the interactions between RNAP and a middle promoter [72, 89, 90, 103]. The RPo formed by RNAP and PuvsX exhibits protein/DNA contacts that are similar to those seen using a typical -35/-10 promoter; addition of MotA in the absence of AsiA does not significantly alter these contacts. As expected, addition of AsiA without MotA inhibits the formation of a stable complex. However, in the presence of both MotA and AsiA, a unique RPo is observed. This MotA/AsiA activated complex has the expected interactions between RNAP and the -10 element, but it has unique protein-DNA interactions upstream of the -10 element. In particular, σ70 Region 4 does not make its usual contacts with the -35 element DNA; rather MotA binds to the MotA box that overlaps the -35 sequence. As expected, when using fully ADP-ribosylated RNAP there is an abrupt loss of footprint protection just upstream of the MotA box in PuvsX, consistent with the loss of UP element interactions when both α-CTD's are modified; when using RNAP that has not been ADP-ribosylated, the UP elements in PuvsX are protected.

Taken together, these biochemical studies argued that within the activated complex, σ70 Region 2.4 binds tightly to the σ70-dependent -10 element, but the MotA/MotA box interaction is somehow able to replace the contact that is normally made between σ70 Region 4 and the -35 DNA (Figure 4) [89, 103]. The subsequent AsiA/σ70 Region 4 structure [26] (Figure 3B, right) shows just how this can be done. Through its multiple contacts with σ70 residues in Regions 4.1 and 4.2, AsiA remodels Region 4 of σ70. When the AsiA/σ70 complex then binds to core, σ70 Region 4 is incapable of forming its normal contacts with -35 element DNA (Figure 3B, left). In addition, the restructuring of σ70 Region 4 prevents its interaction with the β-flap, allowing the far C-terminal region H5 of σ70 to remain available for its interaction with MotA. Consequently, in the presence of AsiA-associated RNAP, MotA can interact both with the MotA box and with σ70 H5 [77, 97, 104].

σ appropriation at a T4 middle promoter. Cartoon depicting a model of RPo at a T4 middle promoter (colors as in Fig. 1). Interaction of AsiA with σ70 Region 4 remodels Region 4, preventing its interaction with the β-flap or with the -35 region of the DNA. This interaction then facilitates the interaction of MotANTD with σ70 H5 and MotACTD with the MotA box centered at -30. Protein-DNA interactions at σ70 promoter elements downstream of the MotA box (the TGn and -10 elements) are not significantly affected. ADP-ribosylation of Arg265 on each α-CTD, catalyzed by the T4 Alt and ModA proteins, is denoted by the asterisks. The modification prevents the α subunits from interacting with DNA upstream of the MotA box.

Recent work has suggested that additional portions of AsiA, MotA and RNAP may be important for σ appropriation. First, the C-terminal region of AsiA (residues 74-90) may contribute to activation at PuvsX by directly interacting both with the β-flap and with MotANTD. In particular, the AsiA N74D substitution reduces an AsiA/β-flap interaction observed in a 2-hybrid assay and impairs the ability of AsiA to inhibit transcription from a -35/-10 promoter in vitro [116]. This mutation also renders AsiA defective in co-activating transcription from PuvsX in vitro if it is coupled with a σ70 F563Y substitution that weakens the interaction of AsiA with σ70 Region 4 [117]. On the other hand, an AsiA protein with either a M86T or R82E substitution has a reduced capacity to interact with MotANTD in a 2-hybrid assay and yields reduced levels of MotA/AsiA activated transcription from PuvsX in vitro [118]. The M86 and R82 mutations do not affect the interaction of AsiA with σ70 or with the β-flap, and they do not compromise the ability of AsiA to inhibit transcription [118], suggesting that they specifically affect the interaction with MotA. These results argue that AsiA serves as a bridge, which connects σ70, the β-flap, and MotA. However, in other experiments, MotA/AsiA activation of PuvsX is not affected when using AsiA proteins with deletions of this C-terminal region (Δ79-90 and Δ74-90), and even AsiA Δ47-90 still retains some ability to co-activate transcription [72]. Furthermore, the C-terminal half of the AsiA ortholog of the vibrio phage KVP40 (discussed below) has little or no sequence homology with its T4 counterpart yet in the presence of T4 MotA and E. coli RNAP, it effectively co-activates transcription from PuvsX in vitro [119], and NMR analyses indicate that the addition of MotA to the AsiA/σ70 Region 4 complex does not significantly perturb chemical shifts of AsiA residues [104]. Thus, further work is needed to clarify the role of the of AsiA C-terminal region. Finally, very recent work has shown that the inability of T4 motA mutants to plate on the TabG strain arises from a G1249D substitution within β, thereby implicating a region of β that is distinct from the β-flap in MotA/AsiA activation [120]. This mutation is located immediately adjacent to a hydrophobic pocket, called the Switch 3 loop, which is thought to aid in the separation of the RNA from the DNA-RNA hybrid as RNA enters the RNA exit channel [28]. The presence of the β G1249D mutation specifically impairs transcription from T4 middle promoters in vivo, but whether the substitution directly or indirectly affects protein-protein interactions is not yet known [120]. Taken together, these results suggest that MotA/AsiA activation employs multiple contacts, some of which are essential under all circumstances (AsiA with σ70 Regions 4.1 and 4.2, MotA with σ70 H5) and some of which may provide additional contacts perhaps under certain circumstances to strengthen the complex.

Concurrent work with the T4 middle promoter PrIIB2 has yielded somewhat different findings than those observed with PuvsX [121]. PrIIB2 is a TGn/-10 promoter that does not require an interaction between σ70 Region 4 and the -35 element for activity. Thus, the presence of AsiA does not inhibit RPo formation at this promoter. An investigation of the complexes formed at PrIIB2 using surface plasmon resonance revealed that MotA and AsiA together stimulate the initial recognition of the promoter by RNAP. In addition, in vitro transcription experiments indicated that MotA and AsiA together aid in promoter clearance, promoting the formation of the elongating complex. Thus, MotA may activate different steps in initiation, depending on the type of promoter. However, there is no evidence to suggest that the protein/protein and protein/DNA contacts are significantly different with different middle promoters.

Interestingly, AsiA binds rapidly to σ70 when σ70 is free, but binds poorly, if at all, to σ70 that is present in RNAP [122]. The inability of AsiA to bind to σ70 within holoenzyme may be useful for the phage because it ties the activation of middle promoters to the efficiency of early transcription. This stems from the fact that σ70 is usually released from holoenzyme once RNAP has cleared a promoter [[123] and references therein]. Since there is an excess of core relative to σ factors, there is only a brief moment for AsiA to capture σ70. Consequently, the more efficiently the T4 early promoters fire, the more opportunities are created for AsiA to bind to σ70, which then leads to increased MotA/AsiA-dependent middle promoter transcription.

Sigma appropriation in other T4-type phages

Although hundreds of activators of bacterial RNAP are known, the T4 MotA/AsiA system represents the first identified case of sigma appropriation. A search for MotA and AsiA orthologs has revealed several other T4-type phage genomes that contain both motA and asiA genes [[124] and http://phage.bioc.tulane.edu/]. These range from other coliphages (RB51, RB32, and RB69) to more distantly related phages that infect aeromonas (PHG25, PHG31, and 44RR) and acinetobacter (PHG133). In addition, orthologs for asiA have also been found in the genomes of the vibrio phages KVP40 and NT1 and the aeromonas phages PHG65 and Aeh1, even though these genomes do not have a recognizable motA. The KVP40 AsiA protein shares only 27% identity with its T4 counterpart. However, it inhibits transcription by E. coli RNAP alone and co-activates transcription with T4 MotA as effectively as T4 AsiA [119]. Thus, it may be that KVP40 and other phages that lack a MotA sequence homolog, do in fact have a functional analog of the MotA protein. Alternatively, the KVP40 AsiA may serve only as an inhibitor of transcription.

No examples of sigma appropriation outside of T4-type phage have been discovered. Although sequence alignments suggested that the E. coli anti-sigma protein Rsd, which also interacts with σ70, may be a distant member of the AsiA family [119], a structure of the Rsd/sigma Region 4 complex is not consistent with this idea [30]. Recent work has identified a protein (CT663) involved in the developmental pathway of the human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis that shares functional features with AsiA [125]. It binds both to Region 4 of the primary σ (σ66) of C. trachomatis and to the β-flap of core, and it inhibits σ66-dependent transcription. More importantly, like AsiA, it works by remaining bound to the RNAP holoenzyme rather than by sequestering σ66.

Transcription of middle genes by the extension of early transcripts

Even though the expression of middle genes is highly dependent on the activation of middle promoters, isolated mutations within motA and asiA are surprisingly not lethal. Such mutant phage show a DNA delay phenotype, producing tiny plaques on wt E. coli [11, 87]. The replication defect reflects the reduced level of T4 replication proteins, whose genes have MotA-dependent middle promoters. In addition, two T4 replication origins are driven by MotA-dependent transcription from the middle promoters, PuvsY and P34i [126]. However, deletion of either motA [127] or asiA [54] is lethal. Recent work suggests that leakiness of the other nonsense and temperature sensitive mutations provide enough protein for minimal growth [120].

Besides MotA-dependent promoters, middle RNA is also generated by the extension of early transcripts into middle genes. This is because most, if not all, middle genes are positioned downstream of early gene(s) and early promoters. Production of this extended RNA is time-delayed relative to the RNA from the upstream "immediate early (IE)" gene. Thus, middle RNA generated from this extension was originally designated "delayed early" (DE), since it cannot be synthesized until the elongating RNAP reaches the downstream gene(s). Early work (reviewed in [1]) classified genes as IE, DE, or middle based on when and under what conditions the RNA or the encoded protein was observed. IE RNA represents transcripts that are detected immediately after infection and do not require phage protein synthesis. DE RNA requires phage protein synthesis, but this RNA and DE gene products are still detected in a T4 motA- infection. In contrast, the expression of genes that were classified as "middle" is significantly reduced in a T4 motA- infection. In addition, while both DE and "middle" RNA arise after IE transcription, the peak of the RNA that is substantially dependent on MotA is slightly later and lasts somewhat longer than the DE peak. However, it should be noted that these original designations of genes as DE or middle are now known to be somewhat arbitrary. Many, if not all, of these genes are transcribed from both early and middle promoters. In fact, while a microarray analysis investigating the timing of various prereplicative RNAs [128] was generally consistent with known Pe and Pm promoters [4], there were a number of discrepancies, especially between genes that were originally classified as either "DE" or "middle". Thus, it is now clear that both the extension of early transcripts and the activation of middle promoters is important for the correct level of middle transcription.

Early experiments [summarized in [1]] offered evidence that DE RNA synthesis might require a T4 system to overcome Rho-dependent termination sites located between IE and DE genes. First, the addition of chloramphenicol at the start of a T4 infection prevents the generation of DE RNAs, indicating a requirement for protein synthesis and suggesting that phage-encoded factor(s) might be needed for the extension of IE RNAs. Second, in a purified in vitro system using RNAP and T4 DNA, both IE and DE RNA are synthesized unless the termination factor Rho is added. Addition of Rho restricts transcription to IE RNA, indicating that Rho-dependent termination sites are located upstream of DE genes. Third, DE RNA from a specific promoter upstream of gene 32 is not observed in a T4 motA- infection, suggesting that MotA itself may be needed to form or stabilize this DE RNA [129]. It is unlikely that a MotA-dependent gene product, rather than MotA, is responsible for this effect, since the DE transcripts are synthesized before or simultaneously with the activation of middle promoters. Finally, wt T4 does not grow in particular rho mutant alleles, called nusD, that produce Rho proteins with altered activity, and the level of certain DE RNAs and DE gene products in T4/nusD infections is depressed. An initial interpretation of this result was that there is more Rho-dependent termination in a nusD allele, which then depresses the level of DE RNA. T4 suppressors that grow in nusD were subsequently isolated and found to contain mutations within the T4 comC-α (also called goF) gene [130, 131], which expresses an early product.

Given all of these findings, it was postulated that T4 uses an anti-termination system, perhaps like the N or Q systems of phage λ [reviewed in [132]], to actively prevent Rho-dependent termination and that MotA, ComC-α, or another protein is involved in this process. However, comC-α is not essential, and the addition of amino acid analogs, which would generate nonfunctional proteins, has been shown to be sufficient for the synthesis of at least certain DE RNAs [reviewed in [1]]. These results suggest that at least in some cases, translation is simply needed to prevent polarity; consequently, the process of translation itself, rather than a specific factor(s), is sufficient to inhibit Rho termination. If so, the loss of DE RNA observed in the presence of Rho in vitro would be due to the lack of coupled transcription/translation. Thus, when the upstream gene is being translated in an infection in vivo, Rho RNA binding sites would be occluded by ribosomes and consequently unavailable.

More recent work has suggested that Rho may affect DE RNA in vivo because of its ability to bind RNA rather than its termination activity [133, 134]. Sequencing of the rho gene in six nusD alleles has revealed that in five cases, the rho mutation lies within the RNA-binding site of Rho. Furthermore, the addition of such a mutant Rho protein to an in vitro transcription system does not produce more termination but rather results in an altered and complicated pattern of termination. There is actually less termination at legitimate Rho-dependent termination sites, but in some cases, more termination at other sites. Unexpectedly, increasing the amount of the mutant Rho proteins rescues T4 growth in a nusD allele, a result that is not compatible with the mutant Rho promoting more termination. In addition, expression of the Rop protein, an RNA-binding protein encoded by the pBR322 plasmid, also rescues T4 growth in nusD.

Taken together, these results have led to another hypothesis to explain DE RNA. In this model, T4 DE transcripts in vivo are susceptible to nuclease digestion and require a process to limit this degradation. Active translation can prevent this nuclease attack, thus explaining the loss of DE RNA in the presence of chloramphenicol. In addition, a protein that can bind RNA, such as wt Rho, Rop, or perhaps the mutated T4 ComC-α, may also be useful. Thus, the nusD Rho proteins are defective not because they terminate IE transcripts more effectively, but because they have lost the ability of wt Rho to bind and somehow protect the RNA. However, it should be noted that as of yet, there is no evidence identifying a particular nuclease(s) involved in this model. Furthermore, the function of wt comC-α or exactly how Rho or Rop "protect" DE RNA is not known. Recent work has shown that both transcription termination and increased mRNA stability by RNA-binding proteins are involved in the regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes and their viruses [135, 136]. A thorough investigation of these processes in the simple T4 system could provide a powerful tool to understanding this mode of gene regulation.

Conclusion

T4 regulates its development and the timed expression of prereplicative genes by a sophisticated process. In the past few years, we have learned how T4 employs several elegant strategies, from encoding factors to alter the host RNAP specificity to simply degrading the host DNA, in order to overtake the host transcriptional machinery. Some of these strategies have revealed unexpected and fundamentally significant findings about RNAP. For example, studies with T4 early promoters have challenged previous ideas about how the α-CTDs of RNAP affect transcription. Work with host promoters argued that contact between the α-CTDs of RNAP and promoter UP elements or certain activators increases transcription; in particular, α residue Arg265 was crucial for this interaction. Thus, one would expect that modification of Arg265 would depress transcription. However, the activity of certain T4 early promoters actually increases when Arg265 of one of the two RNAP α subunits is ADP-ribosylated. This finding underscores our limited understanding of α-CTD function and highlights how T4 can provide a tool for investigating this subunit of RNAP.

The T4 system has also revealed a previously unknown method of transcription activation called sigma appropriation. This process is characterized by the binding of a small protein, T4 AsiA, to Region 4 of the σ70 subunit of RNAP, which then remodels this portion of polymerase. The conformation of Region 4 in the AsiA/σ70 Region 4 structure differs dramatically from that seen in other structures of primary σ factors and demonstrates that Region 4 has a previously unknown flexibility. Furthermore, studies with the T4 MotA activator have identified the far C-terminal region of σ70 as a target for activation. Prior to the T4 work, it was thought that this portion of σ70, which is normally embedded within the β-flap "hook" of core, is unavailable. Based on the novel strategy T4 employs to activate its middle promoters, we now know how a domain within RNAP can be remodeled and then exploited to alter promoter specificity. It may be that other examples of this type of RNAP restructuring will be uncovered.

The core subunits of bacterial RNAP are generally conserved throughout biology both in structure and in function [reviewed in [137, 138]]. In addition, it is now apparent that eukaryotic RNAP II employs protein complexes that function much like σ factors to recognize different core promoter sequences [[139, 140] and references therein]. Thus, the T4 system, which is simple in components yet complex in details, provides an amenable resource for answering basic questions about the complicated process of transcriptional regulation. Using this system, we have been able to uncover at a molecular level many of the protein/protein and protein/DNA interactions that are needed to convert the host RNAP into a RNAP that is dedicated to the phage. This work has given us "snapshots" of the transcriptionally competent protein/DNA complexes generated by the actions of the T4 proteins. The challenge in the future will be to understand at a detailed mechanistic level how these interactions modulate the various "nuts and bolts" of the RNAP machine.

Abbreviations

- bp:

-

base pair(s)

- ds:

-

double-stranded

- ss:

-

single-stranded

- RPo:

-

open complex

- RPc:

-

closed complex

- R or RNAP:

-

RNA polymerase

- P:

-

promoter

- TGn:

-

-15TGn-13 (extended -10 motif)

- Pe:

-

T4 early promoter

- Pm:

-

T4 middle promoter

- rNTPs:

-

ribonucleoside triphosphates

- wt:

-

wild type.

References

Stitt B, Hinton DM: Regulation of middle-mode transcription. In Molecular biology of bacteriophage T4. Edited by: Karam JD, Drake J, Kreuzer KN, Mosig G, Hall D, Eiserling F, Black L, Spicer E, Kutter E, Carlson K, Miller ES. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994:142-160.

Hinton DM, Pande S, Wais N, Johnson XB, Vuthoori M, Makela A, Hook-Barnard I: Transcriptional takeover by sigma appropriation: remodelling of the sigma70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by the bacteriophage T4 activator MotA and co-activator AsiA. Microbiology 2005, 151: 1729-1740. 10.1099/mic.0.27972-0

Brody E, Rabussay D, Hall D: Regulation of transcription of prereplicative genes. In Bacteriophage T4. Edited by: Mathews CK, Kutter EM, Mosig G, Berget PB. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1983:174-183.

Miller ES, Kutter E, Mosig G, Arisaka F, Kunisawa T, Ruger W: Bacteriophage T4 genome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2003, 67: 86-156. 10.1128/MMBR.67.1.86-156.2003

Wilkens K, Ruger W: Transcription from early promoters. In Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4. Edited by: Karam JD, Drake JW, Kreuzer KN, Mosig G, Hall DH, Eiserling FA, Black LW, Spicer EK, Kutter E, Carlson K, Miller ES. Washington, D. C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994:132-141.

Weisberg R, Hinton DM, Adhya S: Transcriptional Regulation in Bacteriophage. In Encyclopedia of Virology. 3rd edition. Edited by: Mahy BWJ, van Regenmortel MHV. Oxford: Elsevier; 2008:174-186. 174-186 full_text

Hinton DM: Transcription from a bacteriophage T4 middle promoter using T4 motA protein and phage-modified RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 1991, 266: 18034-18044.

Schmidt RP, Kreuzer KN: Purified MotA protein binds the -30 region of a bacteriophage T4 middle-mode promoter and activates transcription in vitro. J Biol Chem 1992, 267: 11399-11407.

Stevens A: New small polypeptides associated with DNA-dependent RNA polymerase of Escherichia coli after infection with bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1972, 69: 603-607. 10.1073/pnas.69.3.603

Stevens A: An inhibitor of host sigma-stimulated core enzyme activity that purifies with DNA-dependent RNA polymerase of E. coli following T4 phage infection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1973, 54: 488-493. 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91447-2

Ouhammouch M, Orsini G, Brody EN: The asiA gene product of bacteriophage T4 is required for middle mode RNA synthesis. J Bacteriol 1994, 176: 3956-3965.

Ouhammouch M, Adelman K, Harvey SR, Orsini G, Brody EN: Bacteriophage T4 MotA and AsiA proteins suffice to direct Escherichia coli RNA polymerase to initiate transcription at T4 middle promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92: 1451-1455. 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1451

Hinton DM, March-Amegadzie R, Gerber JS, Sharma M: Bacteriophage T4 middle transcription system: T4-modified RNA polymerase; AsiA, a sigma 70 binding protein; and transcriptional activator MotA. Methods Enzymol 1996, 274: 43-57. full_text

Browning DF, Busby SJ: The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004, 2: 57-65. 10.1038/nrmicro787

Murakami KS, Darst SA: Bacterial RNA polymerases: the wholo story. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2003, 13: 31-39. 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00005-2

Young BA, Gruber TM, Gross CA: Views of transcription initiation. Cell 2002, 109: 417-420. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00752-3

Paget MS, Helmann JD: The sigma70 family of sigma factors. Genome Biol 2003, 4: 203. 10.1186/gb-2003-4-1-203

Gruber TM, Gross CA: Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu Rev Microbiol 2003, 57: 441-466. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913

Campbell EA, Westblade LF, Darst SA: Regulation of bacterial RNA polymerase sigma factor activity: a structural perspective. Curr Opin Microbiol 2008, 11: 121-127. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.016

Hook-Barnard IG, Hinton DM: Transcription Initiation by Mix and Match Elements: Flexibility for Polymerase Binding to Bacterial Promoters. Gene Regulation and Systems Biology 2007. [http://la-press.com/article.php?article_id=481:275-293]

Helmann JD: RNA polymerase: a nexus of gene regulation. Methods 2009, 47: 1-5. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.12.001

Vassylyev DG, Sekine S, Laptenko O, Lee J, Vassylyeva MN, Borukhov S, Yokoyama S: Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 A resolution. Nature 2002, 417: 712-719. 10.1038/nature752

Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA: Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science 2002, 296: 1285-1290. 10.1126/science.1069595

Murakami KS, Masuda S, Darst SA: Structural basis of transcription initiation: RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 4 A resolution. Science 2002, 296: 1280-1284. 10.1126/science.1069594

Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Chlenov M, Sun JL, Olson CA, Weinman O, Trester-Zedlitz ML, Darst SA: Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Mol Cell 2002, 9: 527-539. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00470-7

Lambert LJ, Wei Y, Schirf V, Demeler B, Werner MH: T4 AsiA blocks DNA recognition by remodeling sigma(70) region 4. Embo J 2004, 23: 2952-2962. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600312

Jain D, Nickels BE, Sun L, Hochschild A, Darst SA: Structure of a ternary transcription activation complex. Mol Cell 2004, 13: 45-53. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00483-0

Vassylyev DG, Vassylyeva MN, Perederina A, Tahirov TH, Artsimovitch I: Structural basis for transcription elongation by bacterial RNA polymerase. Nature 2007, 448: 157-162. 10.1038/nature05932

Malhotra A, Severinova E, Darst SA: Crystal structure of a sigma 70 subunit fragment from E. coli RNA polymerase. Cell 1996, 87: 127-136. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81329-X

Patikoglou GA, Westblade LF, Campbell EA, Lamour V, Lane WJ, Darst SA: Crystal Structure of the Escherichia coli Regulator of sigma(70), Rsd, in Complex with sigma(70) Domain 4. J Mol Biol 2007, 372: 649-659. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.081

Sasse-Dwight S, Gralla JD: KMnO4 as a probe for lac promoter DNA melting and mechanism in vivo. J Biol Chem 1989, 264: 8074-8081.

Kontur WS, Saecker RM, Davis CA, Capp MW, Record MT Jr: Solute probes of conformational changes in open complex (RPo) formation by Escherichia coli RNA polymerase at the lambdaPR promoter: evidence for unmasking of the active site in the isomerization step and for large-scale coupled folding in the subsequent conversion to RPo. Biochemistry 2006, 45: 2161-2177. 10.1021/bi051835v

Saecker RM, Tsodikov OV, McQuade KL, Schlax PE Jr, Capp MW, Record MT Jr: Kinetic studies and structural models of the association of E. coli sigma(70) RNA polymerase with the lambdaP(R) promoter: large scale conformational changes in forming the kinetically significant intermediates. J Mol Biol 2002, 319: 649-671. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00293-0

Erie DA: The many conformational states of RNA polymerase elongation complexes and their roles in the regulation of transcription. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1577: 224-239.

Landick R: The regulatory roles and mechanism of transcriptional pausing. Biochem Soc Trans 2006, 34: 1062-1066. 10.1042/BST0341062

Ciampi MS: Rho-dependent terminators and transcription termination. Microbiology 2006, 152: 2515-2528. 10.1099/mic.0.28982-0

Gilmour DS, Fan R: Derailing the locomotive: transcription termination. J Biol Chem 2008, 283: 661-664. 10.1074/jbc.R700032200

Adhya S, Gottesman M: Control of transcription termination. Annu Rev Biochem 1978, 47: 967-996. 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.004535

Wilkens K, Ruger W: Characterization of bacteriophage T4 early promoters in vivo with a new promoter probe vector. Plasmid 1996, 35: 108-120. 10.1006/plas.1996.0013

Koch T, Raudonikiene A, Wilkens K, Ruger W: Overexpression, purification, and characterization of the ADP-ribosyltransferase (gpAlt) of bacteriophage T4: ADP-ribosylation of E. coli RNA polymerase modulates T4 "early" transcription. Gene Expr 1995, 4: 253-264.

Horvitz HR: Bacteriophage T4 mutants deficient in alteration and modification of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 1974, 90: 739-750. 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90537-3

Horvitz HR: Control by bacteriophage T4 of two sequential phosphorylations of the alpha subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 1974, 90: 727-738. 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90536-1

Depping R, Lohaus C, Meyer HE, Ruger W: The mono-ADP-ribosyltransferases Alt and ModB of bacteriophage T4: target proteins identified. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005, 335: 1217-1223. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.023

Ross W, Gosink KK, Salomon J, Igarashi K, Zou C, Ishihama A, Severinov K, Gourse RL: A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 1993, 262: 1407-1413. 10.1126/science.8248780

Gaal T, Ross W, Blatter EE, Tang H, Jia X, Krishnan VV, Assa-Munt N, Ebright RH, Gourse RL: DNA-binding determinants of the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase: novel DNA-binding domain architecture. Genes Dev 1996, 10: 16-26. 10.1101/gad.10.1.16

Murakami K, Fujita N, Ishihama A: Transcription factor recognition surface on the RNA polymerase alpha subunit is involved in contact with the DNA enhancer element. EMBO J 1996, 15: 4358-4367.

Zou C, Fujita N, Igarashi K, Ishihama A: Mapping the cAMP receptor protein contact site on the alpha subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol 1992, 6: 2599-2605. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01437.x

Tiemann B, Depping R, Gineikiene E, Kaliniene L, Nivinskas R, Ruger W: ModA and ModB, two ADP-ribosyltransferases encoded by bacteriophage T4: catalytic properties and mutation analysis. J Bacteriol 2004, 186: 7262-7272. 10.1128/JB.186.21.7262-7272.2004

Wilkens K, Tiemann B, Bazan F, Ruger W: ADP-ribosylation and early transcription regulation by bacteriophage T4. Adv Exp Med Biol 1997, 419: 71-82.

Sommer N, Salniene V, Gineikiene E, Nivinskas R, Ruger W: T4 early promoter strength probed in vivo with unribosylated and ADP-ribosylated Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: a mutation analysis. Microbiology 2000, 146: 2643-2653.

Kashlev M, Nudler E, Goldfarb A, White T, Kutter E: Bacteriophage T4 Alc protein: a transcription termination factor sensing local modification of DNA. Cell 1993, 75: 147-154.

Severinov K, Kashlev M, Severinova E, Bass I, McWilliams K, Kutter E, Nikiforov V, Snyder L, Goldfarb A: A non-essential domain of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase required for the action of the termination factor Alc. J Biol Chem 1994, 269: 14254-14259.

Tiemann B, Depping R, Ruger W: Overexpression, purification, and partial characterization of ADP-ribosyltransferases modA and modB of bacteriophage T4. Gene Expr 1999, 8: 187-196.

Pene C, Uzan M: The bacteriophage T4 anti-sigma factor AsiA is not necessary for the inhibition of early promoters in vivo. Mol Microbiol 2000, 35: 1180-1191. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01787.x

Sanson B, Uzan M: Dual role of the sequence-specific bacteriophage T4 endoribonuclease RegB. mRNA inactivation and mRNA destabilization. J Mol Biol 1993, 233: 429-446. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1522

Hirano N, Ohshima H, Takahashi H: Biochemical analysis of the substrate specificity and sequence preference of endonuclease IV from bacteriophage T4, a dC-specific endonuclease implicated in restriction of dC-substituted T4 DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res 2006, 34: 4743-4751. 10.1093/nar/gkl553

Carlson K, Lagerback P, Nystrom AC: Bacteriophage T4 endonuclease II: concerted single-strand nicks yield double-strand cleavage. Mol Microbiol 2004, 52: 1403-1411. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04062.x

Stevens A, Rhoton JC: Characterization of an inhibitor causing potassium chloride sensitivity of an RNA polymerase from T4 phage-infected Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1975, 14: 5074-5079. 10.1021/bi00694a007

Orsini G, Ouhammouch M, Le Caer JP, Brody EN: The asiA gene of bacteriophage T4 codes for the anti-sigma 70 protein. J Bacteriol 1993, 175: 85-93.

Adelman K, Orsini G, Kolb A, Graziani L, Brody EN: The interaction between the AsiA protein of bacteriophage T4 and the sigma70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem 1997, 272: 27435-27443. 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27435

Severinova E, Severinov K, Fenyo D, Marr M, Brody EN, Roberts JW, Chait BT, Darst SA: Domain organization of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase sigma 70 subunit. J Mol Biol 1996, 263: 637-647. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0604

Colland F, Orsini G, Brody EN, Buc H, Kolb A: The bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein: a molecular switch for sigma 70-dependent promoters. Mol Microbiol 1998, 27: 819-829. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00729.x

Severinov K, Muir TW: Expressed protein ligation, a novel method for studying protein-protein interactions in transcription. J Biol Chem 1998, 273: 16205-16209. 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16205

Sharma UK, Ravishankar S, Shandil RK, Praveen PV, Balganesh TS: Study of the interaction between bacteriophage T4 asiA and Escherichia coli sigma(70), using the yeast two-hybrid system: neutralization of asiA toxicity to E. coli cells by coexpression of a truncated sigma(70) fragment. J Bacteriol 1999, 181: 5855-5859.

Urbauer JL, Adelman K, Urbauer RJ, Simeonov MF, Gilmore JM, Zolkiewski M, Brody EN: Conserved regions 4.1 and 4.2 of sigma(70) constitute the recognition sites for the anti-sigma factor AsiA, and AsiA is a dimer free in solution. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 41128-41132. 10.1074/jbc.M106400200

Pahari S, Chatterji D: Interaction of bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein with Escherichia coli sigma70 and its variant. FEBS Lett 1997, 411: 60-62. 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00668-6

Simeonov MF, Bieber Urbauer RJ, Gilmore JM, Adelman K, Brody EN, Niedziela-Majka A, Minakhin L, Heyduk T, Urbauer JL: Characterization of the interactions between the bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein and RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 2003, 42: 7717-7726. 10.1021/bi0340797

Sharma UK, Chatterji D: Both regions 4.1 and 4.2 of E. coli sigma(70) are together required for binding to bacteriophage T4 AsiA in vivo. Gene 2006, 376: 133-143. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.02.017

Minakhin L, Niedziela-Majka A, Kuznedelov K, Adelman K, Urbauer JL, Heyduk T, Severinov K: Interaction of T4 AsiA with its target sites in the RNA polymerase sigma70 subunit leads to distinct and opposite effects on transcription. J Mol Biol 2003, 326: 679-690. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01442-0

Dove SL, Hochschild A: Bacterial two-hybrid analysis of interactions between region 4 of the sigma(70) subunit of RNA polymerase and the transcriptional regulators Rsd from Escherichia coli and AlgQ from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 2001, 183: 6413-6421. 10.1128/JB.183.21.6413-6421.2001

Urbauer JL, Simeonov MF, Urbauer RJ, Adelman K, Gilmore JM, Brody EN: Solution structure and stability of the anti-sigma factor AsiA: implications for novel functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99: 1831-1835. 10.1073/pnas.032464699

Pal D, Vuthoori M, Pande S, Wheeler D, Hinton DM: Analysis of regions within the bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein involved in its binding to the sigma70 subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase and its role as a transcriptional inhibitor and co-activator. J Mol Biol 2003, 325: 827-841. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01307-4

Lambert LJ, Schirf V, Demeler B, Cadene M, Werner MH: Flipping a genetic switch by subunit exchange. Embo J 2001, 20: 7149-7159. 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7149

Gilmore JM, Bieber Urbauer RJ, Minakhin L, Akoyev V, Zolkiewski M, Severinov K, Urbauer JL: Determinants of Affinity and Activity of the Anti-Sigma Factor AsiA. Biochemistry 2010, in press.

Sharma UK, Praveen PV, Balganesh TS: Mutational analysis of bacteriophage T4 AsiA: involvement of N- and C-terminal regions in binding to sigma(70) of Escherichia coli in vivo. Gene 2002, 295: 125-134. 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)00831-4

Stevens A: A salt-promoted inhibitor of RNA polymerase isolated from T4 phage-infected E. coli. In RNA Polymerase. Edited by: Losick R, Chamberlin M. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1976:617-627.

Baxter K, Lee J, Minakhin L, Severinov K, Hinton DM: Mutational Analysis of sigma(70) Region 4 Needed for Appropriation by the Bacteriophage T4 Transcription Factors AsiA and MotA. J Mol Biol 2006, 363: 931-944. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.074

Minakhin L, Camarero JA, Holford M, Parker C, Muir TW, Severinov K: Mapping the molecular interface between the sigma(70) subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase and T4 AsiA. J Mol Biol 2001, 306: 631-642. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4445

Gregory BD, Nickels BE, Garrity SJ, Severinova E, Minakhin L, Urbauer RJ, Urbauer JL, Heyduk T, Severinov K, Hochschild A: A regulator that inhibits transcription by targeting an intersubunit interaction of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004, 101: 4554-4559. 10.1073/pnas.0400923101

Severinova E, Severinov K, Darst SA: Inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by bacteriophage T4 AsiA. J Mol Biol 1998, 279: 9-18. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1742

Leirmo S, Harrison C, Cayley DS, Burgess RR, Record MT Jr: Replacement of potassium chloride by potassium glutamate dramatically enhances protein-DNA interactions in vitro. Biochemistry 1987, 26: 2095-2101. 10.1021/bi00382a006

Zou LL, Richardson JP: Enhancement of transcription termination factor rho activity with potassium glutamate. J Biol Chem 1991, 266: 10201-10209.

Orsini G, Kolb A, Buc H: The Escherichia coli RNA polymerase.anti-sigma 70 AsiA complex utilizes alpha-carboxyl-terminal domain upstream promoter contacts to transcribe from a -10/-35 promoter. J Biol Chem 2001, 276: 19812-19819. 10.1074/jbc.M010105200

Orsini G, Igonet S, Pene C, Sclavi B, Buckle M, Uzan M, Kolb A: Phage T4 early promoters are resistant to inhibition by the anti-sigma factor AsiA. Mol Microbiol 2004, 52: 1013-1028. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04038.x

Kolesky S, Ouhammouch M, Brody EN, Geiduschek EP: Sigma competition: the contest between bacteriophage T4 middle and late transcription. J Mol Biol 1999, 291: 267-281. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2953

Mattson T, Richardson J, Goodin D: Mutant of bacteriophage T4D affecting expression of many early genes. Nature 1974, 250: 48-50. 10.1038/250048a0

Mattson T, Van Houwe G, Epstein RH: Isolation and characterization of conditional lethal mutations in the mot gene of bacteriophage T4. J Mol Biol 1978, 126: 551-570. 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90058-X

Uzan M, Brody E, Favre R: Nucleotide sequence and control of transcription of the bacteriophage T4 motA regulatory gene. Mol Microbiol 1990, 4: 1487-1496. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02059.x

Hinton DM, March-Amegadzie R, Gerber JS, Sharma M: Characterization of pre-transcription complexes made at a bacteriophage T4 middle promoter: involvement of the T4 MotA activator and the T4 AsiA protein, a sigma 70 binding protein, in the formation of the open complex. J Mol Biol 1996, 256: 235-248. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0082

March-Amegadzie R, Hinton DM: The bacteriophage T4 middle promoter PuvsX: analysis of regions important for binding of the T4 transcriptional activator MotA and for activation of transcription. Mol Microbiol 1995, 15: 649-660. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02374.x

Stoskiene G, Truncaite L, Zajanckauskaite A, Nivinskas R: Middle promoters constitute the most abundant and diverse class of promoters in bacteriophage T4. Mol Microbiol 2007, 64: 421-434. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05659.x

Cicero MP, Alexander KA, Kreuzer KN: The MotA transcriptional activator of bacteriophage T4 binds to its specific DNA site as a monomer. Biochemistry 1998, 37: 4977-4984. 10.1021/bi972337s

Li N, Sickmier EA, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, White SW: The MotA transcription factor from bacteriophage T4 contains a novel DNA-binding domain: the 'double wing' motif. Mol Microbiol 2002, 43: 1079-1088. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02809.x

Li N, Zhang W, White SW, Kriwacki RW: Solution structure of the transcriptional activation domain of the bacteriophage T4 protein, MotA. Biochemistry 2001, 40: 4293-4302. 10.1021/bi0028284

Finnin MS, Hoffman DW, Kreuzer KN, Porter SJ, Schmidt RP, White SW: The MotA protein from bacteriophage T4 contains two domains. Preliminary structural analysis by X-ray diffraction and nuclear magnetic resonance. J Mol Biol 1993, 232: 301-304. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1384

Gerber JS, Hinton DM: An N-terminal mutation in the bacteriophage T4 motA gene yields a protein that binds DNA but is defective for activation of transcription. J Bacteriol 1996, 178: 6133-6139.

Pande S, Makela A, Dove SL, Nickels BE, Hochschild A, Hinton DM: The bacteriophage T4 transcription activator MotA interacts with the far-C-terminal region of the sigma70 subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol 2002, 184: 3957-3964. 10.1128/JB.184.14.3957-3964.2002

Finnin MS, Cicero MP, Davies C, Porter SJ, White SW, Kreuzer KN: The activation domain of the MotA transcription factor from bacteriophage T4. Embo J 1997, 16: 1992-2003. 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1992

Guild N, Gayle M, Sweeney R, Hollingsworth T, Modeer T, Gold L: Transcriptional activation of bacteriophage T4 middle promoters by the motA protein. J Mol Biol 1988, 199: 241-258. 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90311-7

Marshall P, Sharma M, Hinton DM: The bacteriophage T4 transcriptional activator MotA accepts various base-pair changes within its binding sequence. J Mol Biol 1999, 285: 931-944. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2373

Truncaite L, Piesiniene L, Kolesinskiene G, Zajanckauskaite A, Driukas A, Klausa V, Nivinskas R: Twelve new MotA-dependent middle promoters of bacteriophage T4: consensus sequence revised. J Mol Biol 2003, 327: 335-346. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00125-6

Truncaite L, Zajanckauskaite A, Nivinskas R: Identification of two middle promoters upstream DNA ligase gene 30 of bacteriophage T4. J Mol Biol 2002, 317: 179-190. 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5407

Sharma M, Marshall P, Hinton DM: Binding of the bacteriophage T4 transcriptional activator, MotA, to T4 middle promoter DNA: evidence for both major and minor groove contacts. J Mol Biol 1999, 290: 905-915. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2928