Abstract

To investigate West Nile virus (WNV) circulation in rural populations in Gabon, we undertook a large serological survey focusing on human rural populations, using two different ELISA assays. A sample was considered positive when it reacted in both tests. A total of 2320 villagers from 115 villages were interviewed and sampled. Surprisingly, the WNV-specific IgG prevalence was high overall (27.2%) and varied according to the ecosystem: 23.7% in forested regions, 21.8% in savanna, and 64.9% in the lakes region. The WNV-specific IgG prevalence rate was 30% in males and 24.6% in females, and increased with age. Although serological cross-reactions between flaviviruses are likely and may be frequent, these findings strongly suggest that WNV is widespread in Gabon. The difference in WNV prevalence among ecosystems suggests preferential circulation in the lakes region. The linear increase with age suggests continuous exposure of Gabonese populations to WNV. Further investigations are needed to determine the WNV cycle and transmission patterns in Gabon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Findings

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne RNA virus belonging to the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae. Although human WNV infection is generally asymptomatic or causes a 'flu-like illness, life-threatening neurological complications such as meningoencephalitis and flaccid paralysis have been reported [1]. WNV is transmitted in the wild through an enzootic cycle involving birds and ornithophilic mosquitoes [2, 3]. WNV has been widely reported thorough the world, including in many African countries [2, 4]. However, the distribution of WNV is poorly documented in central Africa. Serological evidence of human exposure to WNV has been reported in the Central African Republic [5], Cameroon [6] and the Democratic Republic of Congo [7], with IgG prevalence rates ranging from 6.6% to 59%. The human WNV IgG prevalence has not been investigated in Gabon. The recent occurrence of a human case with neurological manifestations in Libreville [8] during concomitant chikungunya and dengue outbreaks [9], as well as the detection of specific IgG in horses in some Gabonese cities [10], led us to assess the circulation of WNV in Gabon. We undertook a large serological survey focusing on rural human population and using two ELISA assays: a commercial indirect West Nile virus IgG kit (Panbio diagnostics, Australia) and an ELISA method that has been extensively validated against a serum neutralisation test [11]. We considered as WNV IgG-positive all samples reacting in the two ELISA tests.

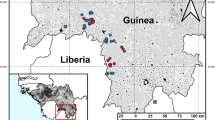

A total of 2320 villagers were interviewed, of whom 1869 (80%) lived in forested regions, 243 (11%) in savannas, and 208 (9%) in the lakes region (Table 1). The WNV-specific IgG prevalence was 27.2% overall (631/2320), 23.7% (443/1869) in the forests, 21.8% (53/243) in the savannas, and 64.9% (135/208) in the lakes region (Figure 1). The villager sample comprised 47.2% of males (1096/2320) and 52.8% of females (1224/2320), and the corresponding WNV IgG prevalence rates were respectively 30% (329/1096) and 24.6% (302/1224). The WNV IgG prevalence rate increased with age from 20.1% (119/591) in the 13-35 year age group to 30.7% (177/576) in the over-60 age group.

Surprisingly, the overall WNV-specific IgG prevalence was high, at levels similar to those found in countries hit by outbreaks. During the WNV outbreaks that occurred in Sudan in 1898 [12] and in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 1988 [7], WNV-specific IgG was found in respectively 59% and 66% of subjects (both IgG and IgM in DRC). During interepidemic periods in Egypt in 1991 [13], Uganda in 1984 [14], and the Central African Republic (CAR) in 1975 [15] and 1979 [16], the WNV-specific IgG prevalence rates were respectively 20%, 16%, 3% and 55%. In countries with no reported clinical cases or WNV isolation, WNV-specific IgG prevalence rates ranged from 0.9% in Kenya in 1987 [17] to 6.6% in Cameroon in 2000 [6] and 27.9% in Ghana in 2008 [18]. The high WNV-specific IgG prevalence detected in this survey suggests that this virus circulates actively in Gabon, despite the lack of reported clinical cases and the low prevalence (about 3%, 2/64) [10] detected in horses sampled in three Gabonese cities. This surprising result may be explained by several factors. Firstly, WNV-specific IgG might arise from aborted WNV infection and antigenic stimulation. Secondly, the lack of reported WNV outbreaks or even isolated cases could be due to the circulation of less virulent WNV strains. Clinical cases may be misdiagnosed and attributed to a similar disease such as malaria or another arbovirosis [19]. Finally, positive serologies might be due to cross-reactions with dengue or yellow fever antibodies, as IgG cross-reactions between flaviviruses have been extensively described in other studies [20, 21] and these viruses are known to circulate in several regions of Gabon [9, 22].

These preliminary results strongly suggest that WNV circulation is widespread in Gabon. The linear increase in WNV IgG prevalence with age suggests continuous exposure of Gabonese populations to this virus. Moreover, although serological cross-reactions due to non specific WNV antibodies could not been ruled out, the larger difference in the prevalence rates between the different ecosystems suggests preferential WNV circulation in the lakes region. This may be explained by specific ecological features such as mosquito vector species or a higher density of residental and migratory birds [23].

In conclusion, this first serological survey of West Nile virus in Gabonese human populations shows widespread circulation of this virus. Further investigations are needed to determine the WNV cycle and transmission patterns in Gabon.

References

Hayes EB, Sejvar JJ, Zaki SR, Lanciotti RS, Bode AV, Campbell GL: Virology, pathology, and clinical manifestations of West Nile virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2005, 11: 1174-1179.

Murgue B, Zeller H, Deubel V: The ecology and epidemiology of West Nile virus in Africa, Europe and Asia. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2002, 267: 195-221.

Rappole JH, Hubalek Z: Migratory birds and West Nile virus. J Appl Microbiol 2003,94(Suppl):47S-58S. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.6.x

Blitvich BJ: Transmission dynamics and changing epidemiology of West Nile virus. Anim Health Res Rev 2008, 9: 71-86. 10.1017/S1466252307001430

Mathiot CC, Georges AJ, Deubel V: Comparative analysis of West Nile virus strains isolated from human and animal hosts using monoclonal antibodies and cDNA restriction digest profiles. Res Virol 1990, 141: 533-543. 10.1016/0923-2516(90)90085-W

Kuniholm MH, Wolfe ND, Huang CY, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Tamoufe U, LeBreton M, Burke DS, Gubler DJ: Seroprevalence and distribution of Flaviviridae, Togaviridae, and Bunyaviridae arboviral infections in rural Cameroonian adults. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006, 74: 1078-1083.

Nur YA, Groen J, Heuvelmans H, Tuynman W, Copra C, Osterhaus AD: An outbreak of West Nile fever among migrants in Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999, 61: 885-888.

Mandji Lawson J, Mounguengui D, Ondounda M, Nguema Edzang B, Vandji J, Tchoua R: Un cas de méningoencéphalite à virus West Nile à Libreville, Gabon. Médecine Tropicale 2009, 69: 501-502.

Paupy C, Ollomo B, Kamgang B, Moutailler S, Rousset D, Demanou M, Herve JP, Leroy E, Simard F: Comparative Role of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti in the Emergence of Dengue and Chikungunya in Central Africa. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2009.

Cabre O, Grandadam M, Marie JL, Gravier P, Prange A, Santinelli Y, Rous V, Bourry O, Durand JP, Tolou H, Davoust B: West Nile Virus in horses, sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12: 1958-1960.

Niedrig M, Sonnenberg K, Steinhagen K, Paweska JT: Comparison of ELISA and immunoassays for measurement of IgG and IgM antibody to West Nile virus in human sera against virus neutralisation. J Virol Methods 2007, 139: 103-105. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.009

Watts DM, el-Tigani A, Botros BA, Salib AW, Olson JG, McCarthy M, Ksiazek TG: Arthropod-borne viral infections associated with a fever outbreak in the northern province of Sudan. J Trop Med Hyg 1994, 97: 228-230.

Corwin A, Habib M, Watts D, Darwish M, Olson J, Botros B, Hibbs R, Kleinosky M, Lee HW, Shope R, et al.: Community-based prevalence profile of arboviral, rickettsial, and Hantaan-like viral antibody in the Nile River Delta of Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993, 48: 776-783.

Rodhain F, Gonzalez JP, Mercier E, Helynck B, Larouze B, Hannoun C: Arbovirus infections and viral haemorrhagic fevers in Uganda: a serological survey in Karamoja district, 1984. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1989, 83: 851-854. 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90352-0

Sureau P, Jaeger G, Pinerd G, Palisson MJ, Bedaya-N'Garo S: [Sero-epidemiological survey of arbovirus diseases in the Bi-Aka pygmies of Lobaye, Central African Republic]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 1977, 70: 131-137.

Saluzzo JF, Gonzalez JP, Herve JP, Georges AJ: [Serological survey for the prevalence of certain arboviruses in the human population of the south-east area of Central African Republic (author's transl)]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales 1981, 74: 490-499.

Morrill JC, Johnson BK, Hyams C, Okoth F, Tukei PM, Mugambi M, Woody J: Serological evidence of arboviral infections among humans of coastal Kenya. J Trop Med Hyg 1991, 94: 166-168.

Wang W, Sarkodie F, Danso K, Addo-Yobo E, Owusu-Ofori S, Allain JP, Li C: Seroprevalence of west nile virus in ghana. Viral Immunol 2009, 22: 17-22. 10.1089/vim.2008.0066

Borgherini G, Poubeau P, Staikowsky F, Lory M, Le Moullec N, Becquart JP, Wengling C, Michault A, Paganin F: Outbreak of chikungunya on Reunion Island: early clinical and laboratory features in 157 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 44: 1401-1407. 10.1086/517537

Sanchez MD, Pierson TC, McAllister D, Hanna SL, Puffer BA, Valentine LE, Murtadha MM, Hoxie JA, Doms RW: Characterization of neutralizing antibodies to West Nile virus. Virology 2005, 336: 70-82. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.020

Monath TP, Heinz X: Flaviviruses in Fields Virology. Raven Third edition. 1996.

Georges AJ, Leroy EM, Renaut AA, Benissan CT, Nabias RJ, Ngoc MT, Obiang PI, Lepage JP, Bertherat EJ, Benoni DD, et al.: Ebola hemorrhagic fever outbreaks in Gabon, 1994-1997: epidemiologic and health control issues. J Infect Dis 1999,179(Suppl 1):S65-75. 10.1086/514290

Clements JF: Birds of the World: a Checklist. Cornell University Press; 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Performed the experiment: DN, XP, JP. Analyzed the data: XP, DN, EL. Wrote the paper: XP, EL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pourrut, X., Nkoghé, D., Paweska, J. et al. First serological evidence of West Nile virus in human rural populations of Gabon. Virol J 7, 132 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-132

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-132