Abstract

Co-infections with HBV (hepatitis B virus) occur in HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) patients frequently. It has been reported that an effective treatment of HIV can also lead to a suppression of HBV and to anti-HBs seroconversion in HBV-infected patients. Here, we report a spontaneous reactivation of HBV replication in an HIV-infected patient with anti-HBc as the only marker of chronic HBV infection. The patient was known to be coinfected with HIV and HBV for years and the HBV DNA was measured repeatedly at low levels. A significant increase of HBV DNA up to 1.7x107 IU/ml was found accompanied with clinical symptoms of hepatitis. Multiple mutations occurred in the S gene during the flare-up of HBV as shown by sequencing, including I103T, K122R, M133I, F134V, D144E, V164E and L175S. Anti-HIV/HBV treatment led to a resolution of symptoms and to a decrease in the HIV RNA and HBV DNA viral load. It is possible that the accumulated mutations during HBV replication were selected and responsible for the reactivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the family of Hepadnaviridae, affecting an estimated 350 million chronically infected individuals worldwide. Due to the similar transmission routes, HBV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection is common and an estimated 5%-15% of HIV infected patients also have HBV infection [1]. HIV coinfection increases the risk of HBV chronicity and HBV reactivation as well as the risk for the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2, 3].

Reactivation of a former HBV infection can occur spontaneously or triggered by immunosuppressive therapy, immunocompromising diseases, organ transplantation or withdrawal of antiviral drugs [4–8]. HBV precore mutation has been reported to be associated with spontaneous reactivation of HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B [9]. The recurrence of HBV replication in HIV/HBV-coinfected patients has been described due to the interruption of lamivudine therapy, due to resistance to the drug [10, 11] and due to HBV immune-escape or precore mutants [11–13]. However, little is known about the molecular characteristics of HBV that is reactivated spontaneously in HBV/HIV coinfected individuals. Previously, HBsAg immune escape mutants were described in the chronic phase and a flare-up phase of HBV infection of an HBV/HIV infected person [14]. Here we analyzed the HBV sequence changes in an HBV/HIV coinfected patient who suffered from a spontaneous reactivation of HBV.

Methods

Serology

Serum samples were stored at -70°C before analysis. Serological markers of HBV infection were determined using commercial enzyme immunoassay kits (Abbott Laboratories, IL, USA) and confirmed partly with other assays (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany; Dade Behring GmbH, Marburg, Germany). The HBV DNA level was quantified using a commercial real-time fluorescence quantitative kit (Roche) and Versant HBV bDNA assay kit (Siemens).

DNA extraction from sera, PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing of PCR fragments

The HBV DNA was extracted from patient sera using QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and subjected to PCR amplification using the high fidelity Taq polymerase (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The region encoding the HBsAg (nt 2818–888) was amplified using primers FS-S1 5′-GTCACCATATTCTTGGGAAC-3′ (nt 2818–2837) and FS-AS 5′-CATATCCCATGAAGTTAAGG-3′ (nt 888–869) according to the reference sequence AY220698 and cloned into pCR2.1 vector. Five clones of each sample were sequenced.

Results

Clinical features

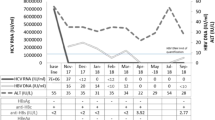

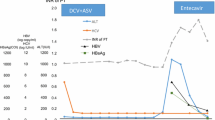

A 60-year-old patient was known to be infected with HIV-1 since 1984. He was diagnosed with a HBV coinfection in July 2003 by HBV serology (HBsAg positive, HBeAg positive and anti-HBc positive) and detectable HBV DNA in the serum. Between October 2003 and August 2007 the HBV DNA fluctuated between 10 to 357 IU/ml while the serological markers of HBV except anti-HBc were negative (Table 1). Since the patient had no HIV-associated symptoms and stable numbers of CD4 positive T helper cells > 500/μl (Figure 1B) with a relatively low HIV viremia (< 100,000 copies/ml) he did not receive a highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).

The ALT, AST, bilirubin levels and lymphocytes counts in an HBV/HIV coinfected patient experiencing a spontaneous HBV reactivation. (A) The ALT, AST and bilirubin levels were monitored regularly from 2006 to 2009. The ALT and AST levels were plotted at the left Y-axis and the bilirubin level at the right Y-axis. The insert indicated the ALT, AST and bilirubin levels during the flare-up phase, the black arrows indicated the sampling time for sequencing. (B) The lymphocytes counts were monitored regularly from 2006 to 2009. The relative CD4+ T cell counts in the CD3+ T cell population (CD4 +%) was set at the right Y-axis. The black arrow indicated the start of the antiviral therapy.

In April 2008 the patient was admitted to hospital due to an acute icteric hepatitis with elevated serum transaminases (AST and ALT > 1000 U/mL) and cholestasis (total bilirubin more than 9.2 mg/dl) (Figure 1A). HBV serologiy (HBsAg, HBeAg and anti-HBc positive) and PCR (HBV DNA >17.86 million IU/ml) showed an exacerbation of chronic HBV infection. At the same time the HIV viral load was 53,000 copies/ml (Table 1). The presence of a co-infection with hepatitis D virus (HDV) was excluded serologically.

The patient was treated with HIV/HBV-active therapy (emtricitabine 200 mg, tenofovir 245 mg (Truvada ®) 1-0-0 , lopinavir 200 mg, ritonavir 50 mg (Kaletra ®) 2-0-2 ), and hereby a rapid virological response was achieved with HBV and HIV viremia decreasing below the limits of detection. The response to antiviral therapy was accompanied by a clinical improvement of the patient, a normalization of the transaminases and of the cholestasis parameters. Anti-HBs seroconversion was achieved 7 months later and was preceded by a phase of simultaneous detection of HBsAg and anti-HBs at 4 months after treatment as it is seen often in clinical routine. Interestingly in the long term anti-HBs declined below the detection limit and anti-HBc again remained the only positive serological HBV marker. During the entire course no significantly change of CD3 + CD4+ T-lymphocytes and the NK CD3-/CD16/56 was found; the counts of CD3 + CD8+ and total CD3+ T-lymphocytes was elevated temporarily after the HAART treatment was started, and the counts of CD19+ lymphocytes was at low level likely due to a splenectomy conducted previously due to a trauma.

HBV mutations in the S and the Pol genes

HBV DNA fragments were amplified from 5 serum samples, three of which were collected in the early chronic phase of infection and two were collected during the flare-up phase, while other samples were negative in the HBV PCR due to the low HBV viral loads. A HBV genotype A HBsAg subtype adw2 strain was found in the chronic phase and the HBV population was homogenous at the time of the first diagnosis of HBV infection. However, the HBV population during the flare-up phase was found to be heterogeneous with multiple amino acid (aa) substitutions within the HBsAg a-determinant. Particularly, the subtype determinant aa 122 K was replaced by R gradually in the flare-up samples. More aa substitutions were found, including I103T, M133I, F134V, D144E, V164E and L175S in the HBsAg (Table 2) and T45S, N122D, V133G/N and W144G in the HBV RT sequence (Table 3). In contrast, the HBV preC/C region was also sequenced and no mutation was found during the same time period.

Discussion

In the present case anti-HBc was the only detectable HBV marker (“anti-HBc only status” [15, 16]) between October 2003 and October 2007. The HBV DNA fluctuated between 10 to 357 IU/ml, indicating an occult chronic HBV infection. Several explanations have been declared for ‘anti-HBc only’ status, including false positive detection of anti-HBc, low replication level of HBV, HBV mutations, coinfection with other viruses and formation of HBsAg-anti-HBs immune complexes [17]. Anti-HBc only serostatus has been described frequently among individuals coinfected with HIV or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection [18, 19]. It is advised to monitor such patients at regular intervals by HBV serology [15, 20] and the HBV DNA should be investigated in case of elevated transaminases [18].

Although about 17-42% of patients coinfected with HIV/HBV have anti-HBc only, there are few reports on the reactivation of HBV in these patients [20, 21]. Previously, Chamorro et al. reported on a reactivation of HBV after the removal of lamivudine in an HIV-infected patient with anti-HBc as the only serological marker [22]. In the present case, the reactivation of HBV occurred spontaneously in a patient with a stable CD4+ T cell count who had not received antiretroviral drugs for years before the hepatic flare. An interesting finding is that the K to R mutation at s122 occurred during the flare-up phase and led to the change of the HBV serotype from adw to ayw. Most of the other aa substitution in the HBsAg found during the flare-up phase described here have been reported before and in combination with the K122R mutation, possibly causing HBV escape from anti-HBs. Amino acid substitutions, which change the hydrophilicity, the electrical charge or the acidity could change the conformation of the a-determinant [23]. M133I and D144E mutation were reported to cause a reduced HBsAg affinity to anti-HBs [24, 25]. F134V mutation was supposed to be a vaccine induced escape mutant [26] and L175S mutation was found in patients with HBsAg-anti-HBs coexistence [27]. The replication competence of HBV strains from different time points need to be compared.

The question was raised whether the hepatitis flare in this patient could be interpreted as a superinfection. However, this patient was constantly positive for HBV DNA for many years. The sequence analysis revealed that the HBV preC/C region was strictly conserved during the course of infection, an evidence preferably for reactivation. Another point for dispute is the fact that there was no obvious pressure by anti-HBs responses for the selection of escape mutations. However, Weinberger et al. [28] indicated that the variability of the major hydrophilic loop of HBsAg was raised significantly in individuals with anti-HBc only compared with HBsAg positive individuals. The patient in this study was positive for anti-HBc only for a long period and represents a typical case of such status. The anti-HBc only status during the chronic phase might be due to the control of HBV replication by the immune surveillance and/or due to the detection escape mutation that may occurred early in the chronic phase. The mutations may have accumulated under these pressures and became the dominant strain. In addition, it is possible that the patient had a low anti-HBs response which remained under the detection limit due to HIV infection. We also detected anti-HBc IgM in the patient during chronic HBV infection and in the flare-up phase. Although normally the appearance of anti-HBc IgM indicates a new infection, it may also be detected during HBV reactivation [29, 30]. Therefore, we could not completely rule out the possibility of superinfection but do not have evidence favoring this hypothesis.

Before the hepatitis flare, the patient did not receive any antiviral treatment, immunosuppressive therapy, or radiation treatment, which may be related to HBV reactivation [31, 32]. It seems that the reactivation happened spontaneously. The accumulation and selection of HBV escape mutants might be one important factor. On the other hand, the immune suppression caused by HIV infection probably also played a role in HBV reactivation. Previously, interleukin-6 (IL-6) was proven to serve as the main bystander mediator of radiotherapy induced HBV replication and IL-6 and radiotherapy have synergistic effect [33]. However, it is not clear whether the cytokine profile was changed in this patient and related to the reactivation.

In conclusion, we reported on a case of spontaneous HBV reactivation in an HIV coinfected patient with isolated anti-HBc, in which the escape mutants in s gene might be responsible for the flare-up. Continued monitoring of the patient with respect to HIV and HBV is necessary for recognizing a possible re-flare of the HBV infection. Retrospectively, the reactivation of HBV might already have been diagnosed in August 2007 when HBsAg and HBV DNA tested positive as indicated from Table 1.

Consent

A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Alter MJ: Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol 2006, 44: S6-S9.

Bodsworth NJ, Cooper DA, Donovan B: The influence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection on the development of the hepatitis B virus carrier state. J Infect Dis 1991, 163: 1138-1140. 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1138

Vento S, Di Perri G, Garofano T, Concia E, Bassetti D: Reactivation of hepatitis B in AIDS. Lancet 1989, 2: 108-109.

Hoofnagle JH: Reactivation of hepatitis B. Hepatology 2009, 49: S156-S165. 10.1002/hep.22945

Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ: Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol 2000, 62: 299-307. 10.1002/1096-9071(200011)62:3<299::AID-JMV1>3.0.CO;2-0

Esteve M, Saro C, Gonzalez-Huix F, Suarez F, Forne M, Viver JM: Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: need for primary prophylaxis. Gut 2004, 53: 1363-1365. 10.1136/gut.2004.040675

Marcellin P, Giostra E, Martinot-Peignoux M, Loriot MA, Jaegle ML, Wolf P, Degott C, Degos F, Benhamou JP: Redevelopment of hepatitis B surface antigen after renal transplantation. Gastroenterology 1991, 100: 1432-1434.

Hui CK, Cheung WW, Au WY, Lie AK, Zhang HY, Yueng YH, Wong BC, Leung N, Kwong YL, Liang R, Lau GK: Hepatitis B reactivation after withdrawal of pre-emptive lamivudine in patients with haematological malignancy on completion of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gut 2005, 54: 1597-1603. 10.1136/gut.2005.070763

Laskus T, Rakela J, Tong MJ, Persing DH: Nucleotide sequence analysis of the precore region in patients with spontaneous reactivation of chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci 1994, 39: 2000-2006. 10.1007/BF02088138

Altfeld M, Rockstroh JK, Addo M, Kupfer B, Pult I, Will H, Spengler U: Reactivation of hepatitis B in a long-term anti-HBs-positive patient with AIDS following lamivudine withdrawal. J Hepatol 1998, 29: 306-309. 10.1016/S0168-8278(98)80017-2

Neau D, Schvoerer E, Robert D, Dubois F, Dutronc H, Fleury HJ, Ragnaud JM: Hepatitis B exacerbation with a precore mutant virus following withdrawal of lamivudine in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. J Infect 2000, 41: 192-194. 10.1053/jinf.2000.0724

Martel N, Cotte L, Trabaud MA, Trepo C, Zoulim F, Gomes SA, Kay A: Probable corticosteroid-induced reactivation of latent hepatitis B virus infection in an HIV-positive patient involving immune escape. J Infect Dis 2012, 205: 1757-1761. 10.1093/infdis/jis268

Costantini A, Marinelli K, Biagioni G, Monachetti A, Ferreri ML, Butini L, Montroni M, Manzin A, Bagnarelli P: Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in an HIV co-infected patient with reactivation of occult HBV infection following discontinuation of lamivudine-including antiretroviral therapy. BMC Infect Dis 2011, 11: 310. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-310

Henke-Gendo C, Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Challapalli D, Trautwein C, Deppe H, Schulz TF, Heim A, Tacke F: Symptomatic hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation despite reduced viral fitness is associated with HBV test and immune escape mutations in an HIV-coinfected patient. J Infect Dis 2008, 198: 1620-1624. 10.1086/592987

Grob P, Jilg W, Bornhak H, Gerken G, Gerlich W, Gunther S, Hess G, Hudig H, Kitchen A, Margolis H, et al.: Serological pattern “anti-HBc alone”: report on a workshop. J Med Virol 2000, 62: 450-455. 10.1002/1096-9071(200012)62:4<450::AID-JMV9>3.0.CO;2-Y

Alhababi F, Sallam TA, Tong CY: The significance of ‘anti-HBc only’ in the clinical virology laboratory. J Clin Virol 2003, 27: 162-169. 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00171-3

Ponde RA, Cardoso DD, Ferro MO: The underlying mechanisms for the ‘anti-HBc alone’ serological profile. Arch Virol 2010, 155: 149-158. 10.1007/s00705-009-0559-6

Perez-Rodriguez MT, Sopena B, Crespo M, Rivera A, Gonzalez Del Blanco T, Ocampo A, Martinez-Vazquez C: Clinical significance of “anti-HBc alone” in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009, 15: 1237-1241. 10.3748/wjg.15.1237

Berger A, Doerr HW, Rabenau HF, Weber B: High frequency of HCV infection in individuals with isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. Intervirology 2000, 43: 71-76. 10.1159/000025026

Knoll A, Hartmann A, Hamoshi H, Weislmaier K, Jilg W: Serological pattern “anti-HBc alone”: characterization of 552 individuals and clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 2006, 12: 1255-1260.

Gandhi RT, Wurcel A, Lee H, McGovern B, Boczanowski M, Gerwin R, Corcoran CP, Szczepiorkowski Z, Toner S, Cohen DE, et al.: Isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen in human immunodeficiency virus type-1-infected individuals. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 36: 1602-1605. 10.1086/375084

Chamorro AJ, Casado JL, Bellido D, Moreno S: Reactivation of hepatitis B in an HIV-infected patient with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2005, 24: 492-494. 10.1007/s10096-005-1355-1

Kreutz C: Molecular, immunological and clinical properties of mutated hepatitis B viruses. J Cell Mol Med 2002, 6: 113-143. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00317.x

Oon CJ, Lim GK, Ye Z, Goh KT, Tan KL, Yo SL, Hopes E, Harrison TJ, Zuckerman AJ: Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis B virus vaccine variants in Singapore. Vaccine 1995, 13: 699-702. 10.1016/0264-410X(94)00080-7

Kim KH, Lee KH, Chang HY, Ahn SH, Tong S, Yoon YJ, Seong BL, Kim SI, Han KH: Evolution of hepatitis B virus sequence from a liver transplant recipient with rapid breakthrough despite hepatitis B immune globulin prophylaxis and lamivudine therapy. J Med Virol 2003, 71: 367-375. 10.1002/jmv.10503

Carman WF, Zanetti AR, Karayiannis P, Waters J, Manzillo G, Tanzi E, Zuckerman AJ, Thomas HC: Vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. Lancet 1990, 336: 325-329. 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91874-A

Zhang JM, Xu Y, Wang XY, Yin YK, Wu XH, Weng XH, Lu M: Coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and heterologous subtype-specific antibodies to HBsAg among patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007, 44: 1161-1169. 10.1086/513200

Weinberger KM, Bauer T, Bohm S, Jilg W: High genetic variability of the group-specific a-determinant of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and the corresponding fragment of the viral polymerase in chronic virus carriers lacking detectable HBsAg in serum. J Gen Virol 2000, 81: 1165-1174.

Gupta S, Govindarajan S, Fong TL, Redeker AG: Spontaneous reactivation in chronic hepatitis B: patterns and natural history. J Clin Gastroenterol 1990, 12: 562-568. 10.1097/00004836-199010000-00015

Brunetto MR, Cerenzia MT, Oliveri F, Piantino P, Randone A, Calvo PL, Manzini P, Rocca G, Galli C, Bonino F: Monitoring the natural course and response to therapy of chronic hepatitis B with an automated semi-quantitative assay for IgM anti-HBc. J Hepatol 1993, 19: 431-436. 10.1016/S0168-8278(05)80554-9

Chou CH, Chen PJ, Lee PH, Cheng AL, Hsu HC, Cheng JC: Radiation-induced hepatitis B virus reactivation in liver mediated by the bystander effect from irradiated endothelial cells. Clin Cancer Res 2007, 13: 851-857. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2459

Wijaya I, Hasan I: Reactivation of hepatitis B virus associated with chemotherapy and immunosuppressive agent. Acta Med Indones 2013, 45: 61-66.

Chou CH, Chen PJ, Jeng YM, Cheng AL, Huang LR, Cheng JC: Synergistic effect of radiation and interleukin-6 on hepatitis B virus reactivation in liver through STAT3 signaling pathway. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 75: 1545-1552. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.072

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Ms. Daniela Catrini for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ms. Thekla Kemper for her technical support. This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Priorities Program of China (2013CB911101) and the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant 31200699). Mengji Lu is supported by German Research Foundation (DFG grants TRR60, GK1045/2, and GK1949).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RJP carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment and drafted the manuscript. SG, JV and SE provided the clinical data and revised the manuscript. XWC and MJL conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Pei, R., Grund, S., Verheyen, J. et al. Spontaneous reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in an HIV coinfected patient with isolated anti-Hepatitis B core antibodies. Virol J 11, 9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-11-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-11-9