Abstract

The climatic cycles with subsequent glacial and intergalcial periods have had a great impact on the distribution and evolution of species. Using genetic analytical tools considerably increased our understanding of these processes. In this review I therefore give an overview of the molecular biogeography of Europe. For means of simplification, I distinguish between three major biogeographical entities: (i) "Mediterranean" with Mediterranean differentiation and dispersal centres, (ii) "Continental" with extra-Mediterranean centres and (iii) "Alpine" and/or "Arctic" with recent alpine and/or arctic distribution patterns. These different molecular biogeographical patterns are presented using actual examples.

Many "Mediterranean" species are differentiated into three major European genetic lineages, which are due to glacial isolation in the three major Mediterranean peninsulas. Postglacial expansion in this group of species is mostly influenced by the barriers of the Pyrenees and the Alps with four resulting main patterns of postglacial range expansions. However, some cases are known with less than one genetic lineage per Mediterranean peninsula on the one hand, and others with a considerable genetic substructure within each of the Mediterranean peninsulas, Asia Minor and the Maghreb. These structures within the Mediterranean sub-centres are often rather strong and in several cases even predate the Pleistocene.

For the "Continental" species, it could be shown that the formerly supposed postglacial spread from eastern Palearctic expansion centres is mostly not applicable. Quite the contrary, most of these species apparently had extra-Mediterranean centres of survival in Europe with special importance of the perialpine regions, the Carpathian Basin and parts of the Balkan Peninsula.

In the group of "Alpine" and/or "Arctic" species, several molecular biogeographical patterns have been found, which support and improve the postulates based on distribution patterns and pollen records. Thus, genetic studies support the strong linkage between southwestern Alps and Pyrenees, northeastern Alps and Carpathians as well as southeastern Alps and the Dinaric mountain systems, hereby allowing conclusions on the glacial distribution patterns of these species. Furthermore, genetic analyses of arctic-alpine disjunct species support their broad distribution in the periglacial areas at least during the last glacial period.

The detailed understanding of the different phylogeographical structures is essential for the management of the different evolutionary significant units of species and the conservation of their entire genetic diversity. Furthermore, the distribution of genetic diversity due to biogeographical reasons helps understanding the differing regional vulnerabilities of extant populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Distributions of animal and plant species are extremely variable in time and space [1–9]. Thus, the strong climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene [10] repeatedly forced many species to major latitudinal and/or altitudinal range shifts [1–4]. These range changes were postulated based on chorological analysis (i.e. localisation of the core areas of distributions) [1, 2, 11–14], and could be traced through fossil records, e.g. from pollen [15–18], charcoal fragments [19], the elytra of beetles [20–22], remains of small mammals [23] and gastropod shells [24–26]. Many of these evidences were supported by genetic analyses [5–9]. However, the resolution of such genetic analyses often exceeds that of the classical methods, and even some cases are known in which the molecular methods unravel misinterpretations of chorological analyses and shortcomings of the other classical methods [8, 27–30].

In this short review, I give a brief overview of the molecular biogeography in the western Palearctic. In the following, I distinguish between three major biogeographic groups in Europe: (i) "Mediterranean" species with Mediterranean differentiation and expansion centres, (ii) "Continental" species with extra-Mediterranean centres and (iii) "Alpin" and/or "Arctic" species, which are found in alpine and/or arctic centres of retreat today. For each of these three groups, I give a brief overview of the main ice-age distributions patterns, of the postglacial range changes and their consequences on the genetic structure.

To test biogeographical patterns, one should select model species fulfilling the following criteria: (i) the species must have a sufficiently high dispersal ability to spread rapidly into newly emerging suitable habitats ensuring that the species occupies the available space, (ii) once established, populations must be large and stable to reflect large scale structures (i.e. phylogeographic signals) and not recent local population structures, and (iii) although having a high dispersal ability, the single individual has to be mostly sedentary so that the phylogeographic patterns are not blurred as for example in migratory species. These criteria are well accomplished by many butterfly and burnet species. Furthermore, quite representative examples for the biogeographical groups mentioned above are known for this group of animals, which therefore is used as preferred model group in this review.

For the classification of the biogeographical groups, I use the definition of faunal elements sensu de Lattin [2] referring to the last dispersal centre and not to the recent distribution pattern of a taxon. The latter is commonly used in plants whereas the former is often applied in zoogeography [31]. Thus, the recent distribution of a Mediterranean element sensu de Lattin [2] can reach Scandinavia in the North, but it is considered Mediterranean, if the last refugium was in the Mediterranean Basin expanding northwards in the postglacial.

Mediterranean species

The three major Mediterranean peninsulas of Europe as glacial refugia

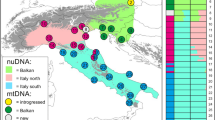

Almost all European species of Mediterranean origin have had their ice-age refugia in at least one of the three major European peninsulas of the Mediterranean area (i.e. Iberia, Italy and the Balkans; Figure 1), and most of the more widespread species had ice-age refugia in all the three of them [4–6, 9]. In the majority of cases, the populations of these three peninsulas had no or only limited exchange of individuals and thus the populations of these disjuncted areas evolved independently often resulting in three major genetic groups, one for each of these peninsulas as shown for a large number of different animal and plant species [4, 6, 9]. These structures were also found in butterflies, as in the chalk-hill blues Polyommatus coridon/hispana complex (Figure 2) [32, 33], the marbled whites Melanargia galathea/lachesis complex [34] and the adonis blue Polyommatus bellargus [35].

However, some cases became recently known in which no genetic differentiation among these three refugial centres were detected. Thus, the meadow brown Maniola jurtina only shows two major genetic lineages, one Atlantic-Mediterranean lineage and a Central-Eastern-Mediterranean one (Figure 3) [36]. These allozyme data are supported by morphological data of the male genitalia and of the wings of both sexes [37]. The eastern phylogenetic group most probably is due to considerable gene flow between the Adriatic- and the Pontic-Mediterranean centres during the last ice-age, whereas the Atlantic-Mediterranean area remained isolated. In an allozyme study of the common blue Polyommatus icarus over major parts of Europe no differentiation among the three major European refugial areas has been detected [38], thus supporting constant gene flow for this species on a European scale even during the last ice-age. As the common blue is recently distributed as far north as northern Scandinavia [39] and the arctic parts of Asia [40], a relatively wide European distribution even during glacial periods is feasible, thus making P. icarus not a typical Mediterranean species.

The three major Mediterranean refugial and differentiation centres of Southern Europe during the last ice-age (R1: Atlantic-Mediterranean, R2: Adriatic-Mediterranean, R3: Pontic-Mediterranean) and the geographic location of the five most important contact and hybridisation areas where different biota got into secondary contact during the postglacial range expansion processes (H1: Pyrenees, H2: Alps, H3: western Central Europe, H4: eastern Central Europe, H5: Central Scandinavia. (Based on Taberlet et al. [9] and Hewitt [5]).

Hypothetical distribution patterns of the meadow brown Maniola jurtina in Europe during the last glacial maximum (dark hatched areas). Postglacial expansions are indicated by solid arrows. The postulated actual hybrid zone is shown by the hatched area. Question marks indicate lack of information concerning ancient distribution patterns in the South and present distribution of hybrid populations in the North. Redrawn from Schmitt et. al. [36]; based on Thomson [37] and Schmitt et al. [36].

Refugia within refugia – genetic differentiations within the Mediterranean sub-centres

A sub-division of the large Mediterranean refugia, based on chorological analyses, was previously postulated e.g. by Reinig [41]. These assumptions have recently been supported by genetic analyses, and a large number of taxa show a strong sub-structuring within the Mediterranean sub-centres such as the Maghreb, Iberia, peninsular Italy, the Balkans and Asia Minor.

The Atlantic-Mediterranean element

The Atlantic-Mediterranean refugial area embraces Iberia and the major part of the Maghreb [2] and thus is divided into an African and a European part by the Strait of Gibraltar, and several examples of strongly differentiated taxa north and south of this sea barrier are known, especially in amphibians as in the genera Pleurodeles, Discoglossus, Alytes, Pelobates, Rana and Salamandra [42–51]. This sea water barrier has permanently existed since the end of the Messinian Salinity Crisis about 5.33 Ma ago [52–55], and thus has strongly impeded the migration of sea water intolerant organisms like amphibians. Nevertheless, strongly differentiated genetic lineages on both sides of the Strait of Gibraltar are also known e.g. in the lizard Psammodromus algirus [56] and the butterfly sibling species complex M. galathea/lachesis [34].

In groups of organisms not being strongly restricted in their dispersal by sea (e.g. reptiles, butterflies) relatively recent (e.g. late Pleistocene) exchange of individuals is known, as in several snakes [57, 58], turtles [59, 60], tortoises [61], chameleons [62], butterflies [36], bark beetles [63], but also in the frog Hyla meridionalis [64]. The more southern and thus warmer Maghreb more often represented the centre of origin [47, 57–62, 64–70] than Iberia [56].

In many cases, the Maghreb populations show remarkable east-west differentiations as in the lizard P. algirus [56], the snake Malpolon monspessulanus [58] and the shrew Crocidura russula [70] most probably representing the frequent existence of eastern and western sub-centres of differentiation. In the turtle Mauremys leprosa, the two Maghreb lineages are separated by the Atlas Mts. in Morocco and Algeria with the southern lineage expanding from southern Morocco to the Mediterranean Sea in Tunisia [60]. This distribution matches the Mauretanic-Mediterranean sub-centre postulated by de Lattin [2].

In Iberia, a strong genetic differentiation into a western and an eastern group is also known for a larger number of species as in the case of Pleurodeles newts [47, 48, 66], Discoglossus frogs [50], the burnet moth Aglaope infausta [71], the lizards P. algirus [56] and perhaps Acanthodactylus erythrurus [72]. Paleoclimatology shows that the climatically most favourable areas of Iberia were in disjunct areas in the southwestern and the southeastern parts of the peninsula [73]. Therefore, it is most likely that xero-thermophilic species had two disjunct areas of glacial survival and differentiation in the Iberian Peninsula [71]. However, several of these and other taxa evolved an even more complex genetic structure beyond this simple east-west split [46, 50, 51, 65, 74–80].

Thus, the Iberian lizard species Lacerta schreiberi consists of four major genetic lineages, two coastal clades and two inland clades, most probably representing four disjunct areas of glacial survival in Iberia with only the northern coastal clade becoming expansive during the postglacial [74]. Chioglossa lusitanica, an endemic salamander species of northwestern Iberia, has a none-expansive clade in central Portugal and an expansive clade in northern Portugal and northwestern Spain [81, 82]. The western lineage of P. algirus is further divided into a southern and a northern sub-cluster [56]. As much as six lineages are distinguished in the western Iberian endemic newt Lissotriton boscai, and three of these lineages are confined to southwestern Portugal [80]. These structures strongly support the existence of several sub-refugia in Iberia along the Pleistocene often resulting in remarkable differentiations between genetic lineages.

The southwest of Portugal revealed to be of special importance as refugial area. This is further supported by the rather fine-grained genetic lineages of the cyprinid Squalius aradensis in the Algarve (southern Portugal) [78], and the extremely high haplotype diversity of M. leprosa in southern Portugal [60] underlining the long-term persistence of taxa in this part of Iberia. If postglacial northwards expansions occurred in one of these lineages within Iberia, remarkable genetic impoverishment is the frequently observed result [60, 63, 74, 81, 82] as in other species on the continental scale (see below) [4].

The fire salamander Salamandra salamandra is also present in three lineages in Iberia, one endemic lineage in the south, another in central and northern Iberia, which is the predominant lineage of Europe, and a third one in a limited area in Cantabria that is identical with the one in the southernmost tip of Italy. The origin of the latter is still ambiguous, and the widespread lineage might have entered Iberia only in the postglacial [45]. The Timarchia goettingensis complex shows a highly complex genetic structure in Iberia implying a series of vicariance events and differentiation centres for this beetle [75, 76].

The Adriatic-Mediterranean element

The Adriatic-Mediterranean refugial area is represented by peninsular Italy [2]. As the geographical diversity of this area and the total land mass is considerably less in peninsular Italy than in Iberia, the phylogeographical patterns are considerably simpler in the Adriatic- than in the Atlantic-Mediterranean region. Truly Mediterranean species like the bark beetle Tomicus destruens [63] and the Apennine yellow-bellied toad Bombina pachypus [83] only survived in relatively restricted areas of Calabria and Sicily, and only expanded to more northern regions of Italy when the climate warmed in the postglacial; hereby, they lost genetic diversity. Calabria is particularly rich in strongly differentiated lineages, e.g. four in the Italian wall lizard Podarcis sicula [84], two in S. salamandra [45] and two in B. pachypus [83]. This underlines the great importance of this area as refugial region and its particular substructure. However, Sicily is not differentiated from Calabria in most cases reflecting the close geographic proximity with the peculiar exception of the hedgehog Erinaceus europaeus showing a remarkable genetic differentiation in Sicily [85].

Apart from differentiation centres in southern Italy, several species also show distinct lineages in the northern part of peninsular Italy, such as the lizard P. sicula [84], the grasshopper Chorthippus parallelus [86], the honey bee Apis mellifera [87], and the asp viper Vipera aspis [88], thus underlining the existence of additional allopatric differentiation centres in this region. In some cases different lineages expanding in Italy from the south and the north (the latter sometimes with their roots outside of Italy) have built up hybrid zones in Italy as in the case of the honey bee [87] and the bark beetle T. destruens [63].

The Pontic-Mediterranean element

The Pontic-Mediterranean refugial region sensu de Lattin [2] embraces the Balkan Peninsula, Asia Minor and the east coast of the Mediterranean as far south as Palestine. For this area even Reinig [41] suggested a number of sub-centres, a hypothesis which is strongly supported by recent genetic analyses in this region. Thus, often deep genetic splits between the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor support the long lasting biogeographic isolation of these two areas as e.g. detected in the hedgehog Erinaceus concolor [85, 89], the grasshopper C. parallelus [86], the bark beetle T. destruens [63] and most probably the badger Meles meles [90].

Several genetic data sets support Reinig's idea [41] of several sub-centres in the Balkan Peninsula. Thus, phylogeographic work on the pond turtle Emys orbicularis [59], the fire-bellied toad Bombina variegata [91], the hedgehog E. concolor [85, 89] and the slug Arion fuscus [30] all support an east-west split of the Balkan Peninsula with western Illyrian and eastern Aegean phylogroups. A similar situation was found in the marbled white M. galathea [92]. The allozyme analysis of individuals from southeastern Europe support at least three centres of survival along the Mediterranean coasts of the Balkans: the Illyrian Coast, the Aegean Coast and the southwestern coast of the Black Sea. Whether these three centres of dispersal were linked to each other during the Würm ice-age or not is still unknown.

Old splits in the southern Balkan Peninsula even date back to the formation of the mid-Aegean trench (12 to 9 Ma ago) [93]. This event has been reported to have acted as a major factor determining the biogeographical patterns of scorpions [94, 95] and reptiles [96, 97]. In the scorpion Iurus dufoureius this vicariance is mirrored in a western group from the Peloponnisos to Crete island and an eastern clade from Karpathos island to southwestern Turkey [94]. In other species, more complex genetic patterns evolved with localised endemic lineages especially in the long-term isolated islands of the southern Kyklades and Crete as in the scorpion Mesobuthus gibbosus [95], Podarcis lizards [96, 97] and land snails [98, 99].

Postglacial range expansions: the four paradigms

The postglacial re-colonisation of Central and Northern Europe by Mediterranean species followed in general four paradigm patterns [5, 6, 34]: (i) the hedgehog (postglacial expansion from all three southern European differentiation centres) [100], (ii) the bear (expansion of the western and the eastern lineage, but trapping of the Adriatic-Mediterranean lineage by the Alps, nota bene that the expansion of the eastern lineage in the bear example is not from the Pontic-Mediterranean region but from an eastern continental differentiation centre) [101], (iii) the butterfly (expansion of the Adriatic- and the Pontic-Mediterranean lineages, but trapping of the Atlantic-Mediterranean lineage by the Pyrenees) [34] and (iv) the grasshopper (major expansion to Central Europe only from the Balkans and trapping of the Atlantic- and Adriatic-Mediterranean lineages by the Pyrenees and Alps, respectively) [86].

These paradigms are frequently repeated in many animal and plant species, thus the "hedgehog" paradigm e.g. in oaks Quercus ssp. [102], the silver fir Abies alba [103] and the house mouse Mus musculus [104], the "bear" in e.g. the shrews Sorex araneus [105, 106] and Crocidura suaveolens [9] and the water vole Arvicola terrestris [9] and the "grasshopper" e.g. in the black alder Alnus glutinosa [107], the common beech Fagus sylvatica [108] and the newt Triturus cristatus [109]. Only three examples are actually known for the "butterfly" paradigm: the marbled whites M. galathea/lachesis complex [34], the chalk-hill blues P. coridon/hispana complex (Figure 2) [33] and, based on a small data set, the adonis blue P. bellargus [35]. The latter paradigm might be a common phylogeographical structure for quickly expanding species, so that the Italian lineage might have expanded rapidly, passing westwards south of the Alps and afterwards expanding all over southern France, so that this space had been occupied when individuals of the Iberian lineage started to pass the Pyrenees. However, further examples are needed for this paradigm's support.

Genetic consequences of Postglacial range expansion

The Postglacial range changes had major impact on the genetic conditions of the affected species. Therefore, it is of major importance for the genetic texture whether a species is expanding phalanx like, stepping stone or leptokurtic [110].

In the first case, the species perform only weak genetic differentiation during the process of range expansion, often without loss of genetic diversity. Such structures are characteristic for species with wide ecological amplitudes and were also found in common butterfly species like in the green-veined white Pieris napi [111, 112], the common blue P. icarus [38], the small tortoiseshell Aglais urticae [113], the meadow brown M. jurtina [36] and the marbled white M. galathea [34]. All these species do not show significant losses of their genetic diversity from their expansion centres towards their recent northern distribution border.

On the contrary, stepping stone and leptokurtic dispersal are responsible for the evolution of genetic patterns along the process of expansion often going along with the loss of genetic information during the processes of expansion, as shown for many animal and plant species [114–121]. Such a genetic structure is characteristic for species with specific habitat requirements so that no phalanx can expand, but only some few individuals reach so far unoccupied emerging habitats, as also known for the chalk-hill blue P. coridon. This species shows a linear loss of genetic diversity from the south to the north in its Pontic-Mediterranean lineage [122] and a stepwise loss of genetic diversity in the Adriatic-Mediterranean lineage (i.e. no loss of genetic diversity over larger distances as from southern France to northeastern France, and abrupt reduction of genetic diversity as a decrease of 10% of the number of alleles resulting from the passing through of the Burgundian Gate between the Vosges and the Jura Mts.) [123].

Contact zones in Europe

As a consequence of postglacial range expansion in the group of species of Mediterranean origin, a network of contact zones is spread over Europe (Figure 1). However, these contact zones between different genetic lineages are not randomly scattered over the continent, but show a systematic pattern. Thus, the mountain systems of the Pyrenees and Alps, often acting as dispersal barriers, represent two important areas where different biota met, but also three other regions of Europe show a high number of secondary contact zones between genetic lineages [5, 6, 9]: (i) western Central Europe along the French-German border region and along the western Alps (Figure 3), (ii) eastern Central Europe along the eastern borders of Germany and through the eastern Alps and (iii) running east-west through central Scandinavia.

For butterflies, the meadow brown M. jurtina has a typical contact zone in western Central Europe where the Atlantic-Mediterranean lineage meet with the Central-Eastern-Mediterranean group (Figure 3), which is supported by two allozyme studies, the morphology of the male genitalia and three wing patterns [36, 37]. Along the French-German border regions, no natural obstacles are separating these two lineages; apparently, these lineages have met in that area and the populations, once set up by one evolutionary lineage, remained mostly stable over time; however, some hybridisation in Belgium and the Netherlands is possible, based on the morphology of the male genitalia [37].

Evidence for the eastern Central European contact zone exists e.g. for two butterfly species. The two major genetic lineages of the chalk-hill blue P. coridon, based on allozyme analysis and wing patterns, meet in this region (Figure 2) [32, 33]. Mostly all along this contact zone the natural conditions for the survival of this warm-loving species of calcareous grasslands [124, 125] limit its existence: an acid sandy area in northeastern Germany, acid cold mountains ranges along the Czech-German border region and the watersheds of the eastern Alps [32] so that this contact zone might partly be shaped by natural expansion obstacles too, but not so extreme as in the cases of the Alps and Pyrenees. The Czech-German border mountains also act as contact zone for the woodland ringlet Erebia medusa; these mountains apparently were reached by an eastern and a western lineage early in the postglacial (more details on the molecular biogeography of this continental species in the next chapter), but the high elevations of these mountains could only be colonised by the species some time after its arrival so that the main ridges mostly represent the contact zone between both lineages [126].

Continental species

Formerly, a considerable proportion of the European fauna was considered of eastern Palearctic origin with postglacial expansion from Siberian or Mandshurian refugia throughout Asia to Europe [2]. This postulate has been questioned for a long time e.g. by Varga [3] and recent publications give rising evidence even for the existence of cryptic northern refugia north of the Alps and Pyrenees [127]. Thus, genetic analyses unravel extra-Mediterranean ice-age refugia in Europe in a series of other animal species as in the adder Vipera berus in the Carpathian Basin, areas adjoining the Alps and one or more areas in central Europe [128], in the frog Rana arvalis in the Carpathian Basin [129, 130], the fish Cottus gobio in Germany [131], the voles Microtus arvalis in the Black Forest region and maybe elsewhere in Central Europe [132], Microtus agrestis [133] and Clethrionomys glareolus [28], the ant Formica pratensis in the Pyrenean region [134], the slug Arion fuscus in the region of the High Tatras [30] and the nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus [29]. Thus, extra-Mediterranean ice-age refugia in Europe might be a much more common feature in temperate continental species than previously thought, but more investigation in the field of continental species is urgently needed [127].

A particularly interesting and well studied species in the group of continental species represents the woodland ringlet E. medusa. There is good evidence based on allozyme data that this species had multiple Würm ice-age differentiation centres around the glaciated Alps, in the Carpathian region and in the Balkan Peninsula ([27, 135]; TS unpublished data). This glacial distribution pattern in E. medusa and most probably in other similar species too (one further good example with strikingly similar genetic pattern being the adder [128]) might be due to the particular climatic conditions in Europe during the ice-ages: (i) the climate was predominantly much drier than today and (ii) the continentality of the climate was increasing westwards [10]. Therefore, not only the low temperatures, but also lack of precipitation restricted the distribution of many animal and plant species during the glacial phases of the Pleistocene. While the temperature might have been the major restriction for the distribution of the above discussed Mediterranean species, the dryness might have been even more important for many of the taxa out of the group of continental species. Erebia medusa [136] and V. berus [137] for example are recently distributed in Central Asia in regions with extremely cold winters so that the temperatures in Central Europe during the ice-ages might not have been the main constraint for their distributions. In contrast to temperature, the dryness of Central Europe might have been the limiting factor for the species' glacial distributions in Europe. Therefore, the survival of the woodland ringlet as well as several other species [30, 131, 132, 134, 138, 139] in relatively small areas adjoining the water-donating high mountain systems like the Alps and Carpathians is feasible as well as in the proximity of the high mountain systems of the Balkan Peninsula ([27, 135]; TS unpublished data).

However, there is evidence for some species having colonised Europe postglacially from eastern dispersal centres. This is mostly the case for typical Taiga species like the Russian flying squirrel Pteromys volans [140] and the ant Formica lugubris [134], in which postglacial expansion from eastern Palearctic Würm ice-age refugia is probably based on their genetic texture, but not in a species like the Siberian jay Perisoreus infaustus, in which western and eastern Palearctic populations belong to strongly differentiated phylogroups [141]. In butterflies, the scarce heath Coenonympha hero shows a gradient of declining genetic diversity from the southern Ural Mts. over Estonia to southern Sweden, but no split into different genetic lineages [142]. This structure supports a glacial centre of survival for this species in the southern Urals and postglacial range expansion westwards to Sweden.

The adder V. berus shows in its mtDNA haplotypes the peculiar structure of highly differentiated genetic lineages in Europe, but one lineage stretching from Finland and the Baltic countries throughout Russia to the Sakhalin island [128]. This strongly supports a centre of origin in the western Palearctic and relatively recent (maybe even postglacial) expansion throughout Asia, thus showing an opposed pattern to the classical Siberian element definition sensu de Lattin [2].

Arctic and/or Alpine species

In the past it was thought that "Arctic" and/or "Alpine" species in many cases show an almost opposed pattern to Mediterranean species: they expand during cold stages and become restricted to mountain or Nordic refugia during interglacials [1, 2, 12]. Recent work on arctic and alpine species has revealed that this pattern was an oversimplification. In fact, there is evidence that some arctic animal and plant species survived the last glaciation even at high latitudes or even north of the extensive ice shields; the evidence is strong for Beringia and northeastern Asia, weaker for the High Nearctic and doubtful for northern Europe [8, 143, 144]. In general, two largely different patterns are found in this biogeographical group:

(1) Some species were widely distributed throughout the glacial steppes between the northern ice shield and the glaciers in the mountains of the South, so that a large scale gene flow was only interrupted by the postglacial disjunction into different high mountain systems and the arctic (i.e. arctic-alpine disjunct species). This classical glacial distribution pattern of arctic-alpine species is well supported by fossil evidence [145], but the genetic evidence is still relatively poor [146].

Thus, a common origin of Dryas octopetala from the southern European mountains, Iceland, Scotland and Scandinavia is demonstrated by AFLP analysis [147]. Close genetic relation between arctic populations and such from the southern European mountains are also known for Saxifraga oppositifolia [143], Minuartia biflora [148] and the lycosid Pardosa saltuaria group [149]. Postglacial immigration into Scandinavia from source populations in the eastern Alps was invoked for Ranunculus glacialis because of genetically depauperate populations relative to the otherwise quite similar alpine ones [150]. The genetic structure of the boreo-montane bog fritillary Proclossiana eunomia [151] implies postglacial colonization of Fennoscandia from an eastern refugium, maybe representing the Siberian differentiation centre sensu de Lattin [2]. An eastern origin of Scandinavian populations is also likely in Trollius europaeus [152] and D. octopetala in the northern part [147]. Some genetic evidence for a wide distribution in the glacial steppes and semi-deserts is available for the burnet moth Zygaena exulans with a rather weak differentiation between Alps and Pyrenees [153] and the water beetle Hydroporus glabriusculus with no significant genetic differences among populations from Britain and Scandinavia [154]. The species surviving in these environments have to be adapted not only to rather cold, but also to extremely dry steppic conditions with the latter maybe excluding a large number of the typical alpine species from the periglacial steppe belt.

(ii) Other species have probably been subject to disjunct distribution patterns during glacial and – in many cases – interglacial phases, thus accumulating much larger differentiation than species of the first group [146, 149, 150, 152, 155–168]. Especially the dryness of the glacial steppes and not the low temperatures might have excluded a large number of such cold adapted species from these areas. Therefore, many of these species became restricted to the wetter areas in the proximity of the glaciated mountain systems [146, 167, 168]. Thus, multiple (often four) refugia were scattered for various species (e.g. R. glacialis, Phyteuma globulariifolium, Androsace alpina, Pritzelago alpina, Drusus discolor, Erebia epiphron) along the margins of the southern and eastern Alps [157, 164, 166–168].

Remarkable differentiation of the inner-alpine populations of Eritrichum nanum [155, 160], Saponaria pumila [161], Rumex nivalis [165], Erinus alpinus [159], S. oppositifolia [169] and Androsace wulfeniana [164] even give genetic support for in situ survival in the Alps (i.e. nunatak survival).

Many of the smaller European high mountain systems own their endemic genetic lineages. The populations of these mountain areas often simply performed altitudinal shifts respective to climate changes and no major long distance colonisation. Thus their differentiation centres likely existed at the foot hills of these mountains throughout the last glaciation and often even much longer, as shown for the Cantabrian Mts. (P. eunomia [151], Pritzelago alpina [163]), the Pyrenees (P. alpina [163], D. discolor [167], Pardosa oreophila [149], E. epiphron [168]), the Tatra Mts. (D. discolor [167]), the Stara Planina (P. eunomia [151]) and Pirin & Vitosha (Pardosa drenskii [149]).

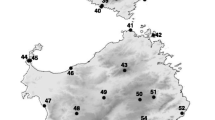

However, there is good genetic evidence for glacial links between the Pyrenees and the southwestern Alps (Anthyllis montana [156], Erebia cassioides [170], E. epiphron [168]), the northern Alps and the Jesenik Mts. (E. epiphron [168]), the northern Carpathians and the northeastern Alps (P. alpina [163], Ranunculus pygmaeus [148]) and the mountains of the western Balkan Peninsula and the southeastern Alps (A. montana [156]) during glacial periods. The postulated five centres of differentiation of the mountain ringlet E. epiphron illustrating the complexity of the patterns found in this biogeographical group are presented in Figure 4[168].

Conservation implications

There is increasing evidence that the population genetic constitution is highly important for the individual fitness [171–173]. Meta-analyses have shown that the sensitivity of the populations to extinction is negatively correlated with the respective regional genetic diversity resulting from their biogeographic history [174]. Therefore, continental species in general are more endangered in the western part of Europe than in the East, whereas Mediterranean species perform better in the genetically richer South than in the North [174].

These analyses underline the high importance for conservation of the populations existing in the areas of the Quaternary refugia: these populations as a whole own most of the total genetic diversity and thus the evolutionary potential of a species [175, 176]. The frequently observed genetic differentiations of marginal races at the high-latitude leading edge are therefore of considerably less evolutionary importance than the low-latitude rear edge populations because (i) the high-latitude edge lineages are mostly due to recent (i.e. postglacial) adaptation processes and not long-term evolution [176] and (ii) most of these lineages may simply disappear leaving no descendants when the climate will become cooler again [175]. However, the high diversity of different biogeographical patterns point out that each species has reacted independently to Pleistocene climatic changes in terms of persistence in a refugium, migration rates and colonisation routes [175]. Therefore, generalisations for conservation measures should be made with extreme care.

Conclusion

Europe shows a great variety of different biogeographical patterns with (i) "Mediterranean", (ii) "Continental" and (iii) "Arctic/Alpine" being the predominant ones.

Within the "Mediterranean" group, (i) one or (ii) more (sometimes phylogeographically highly complex) genetic lineage(s) evolve during glacial isolation within a single Mediterranean peninsula or (iii) two or more peninsulas share a single lineage. Postglacial range expansions follow four main patterns: (i) "Hedgehog", (ii) "Bear", (iii) "Butterfly" and (iv) "Grasshopper" depending on whether Alps and/or Pyrenees acted as postglacial expansion barrier or not. As a consequence of range expansions, biota predominantly got into contact in five regions of Europe: (i) along the Pyrenees' main ridge, (ii) along the Alps' main ridges, (iii) in western Central Europe running north-south, (iv) in eastern Central Europe running north-south and (v) in central Scandinavia running east-west.

In the group of "Continental" species, two major biogeographical types may be distinguished: (i) species with non-Mediterranean glacial refugial and differentiation centres in Europe, with special importance of the continental areas of the Balkan Peninsula, the Carpathian Basin and the perialpine areas around the Alps, with many of these centres of distribution being geographically rather restricted, but in general numerous, and, to a lesser extent, (ii) postglacial expansion from eastern differentiation centres located in Asia with the western most possibility being the southern Ural Mts. The latter species group is mostly composed of typical Taiga species.

The third important pattern, the group of "Arctic" and/or "Alpine" species, consists of two rather different subgroups: (i) species that have been widely distributed in the periglacial steppes during the glacial periods and (ii) taxa that also had disjunct distribution patterns during the ice-ages. The former group splits into (i) species only retreating northwards in the Postglacial (i.e. arctic species) and (ii) species retreating northwards and into the mountain systems in the south (i.e. arctic-alpine species s. str.). The latter group, showing disjunct ice-age distribution patterns, is mostly absent from the high latitudes and often shows a variety of genetic lineages stemming from different glacial differentiation centres, but now coexisting within a single high mountain system, as best demonstrated for the Alps. Furthermore, several biogeographic links between mountain systems are known in this group best explained by glacial distribution patterns as in the links between (i) Pyrenees and southwestern Alps, (ii) Carpathians and northeastern Alps as well as (iii) the Dinaric Mountain system and the southeastern Alps.

Apparently, we know quite a lot about the molecular biogeography of Europe, but many aspects still remain enigmatic. Therefore, further investigation in this field is urgently needed to really understand and conserve the highly complex biogeographical constitution of the European continent.

References

Reinig W: Elimination und Selektion. 1938, Jena, Fischer

de Lattin G: Grundrißder Zoogeographie. 1967, Jena, Fischer

Varga Z: Das Prinzip der areal-analytischen Methode in der Zoogeographie und die Faunenelement-Einteilung der europäischen Tagschmetterlinge (Lepidoptera: Diurna). Acta Biol Debr. 1977, 14: 223-285.

Hewitt GM: Some genetic consequences of ice ages, and their role in divergence and speciation. Biol J Linn Soc. 1996, 58: 247-276. 10.1006/bijl.1996.0035.

Hewitt GM: Post-glacial re-colonization of European biota. Biol J Linn Soc. 1999, 68: 87-112. 10.1006/bijl.1999.0332.

Hewitt GM: The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature. 2000, 405: 907-913. 10.1038/35016000.

Hewitt GM: Speciation, hybrid zones and phylogeography – or seeing genes in space and time. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 537-549. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01202.x.

Hewitt GM: Genetic consequences of climatic oscillation in the Quaternary. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 2004, 359: 183-195. 10.1098/rstb.2003.1388.

Taberlet P, Fumagalli L, Wust-Saucy A-G, Cosson J-F: Comparative phylogeography and postglacial colonization routes in Europe. Mol Ecol. 1998, 7: 453-464. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00289.x.

Williams D, Dunkerley D, DeDecker P, Kershaw P, Chappell M: Quaternary Environments. 1998, London, Arnold

Reinig W: Die Holarktis. 1937, Jena, Fischer

Holdhaus K: Die Spuren der Eiszeit in der Tierwelt Europas. 1954, Innsbruck, Wagener

Dennis RLH, Williams WR, Shreeve TG: Faunal structures among European butterflies: evolutionary implications of bias for geography, endemism and taxonomic affiliations. Ecography. 1998, 21: 181-203. 10.1111/j.1600-0587.1998.tb00672.x.

Hausdorf B, Hennig C: Does vicariance shape biotas? Biogeographical tests of the vicariance model in the north-west European land snail fauna. J Biogeogr. 2004, 31: 1751-1757. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01090.x.

Huntley B, Birks HJB: An atlas of past and present pollen maps of Europe: 0–13000 years ago. 1983, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Gliemeroth AK: Paläoökologische Untersuchungen über die letzten 22.000 Jahre in Europa. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Paläoklimaforschung 18. Stuttgart, Fischer. 1995

Willis KJ, Sümegi P, Braun M, Toth A: The late Qarternary environmental history of Bátorliget, NE Hungary. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimat Palaeoecol. 1995, 118: 25-47. 10.1016/0031-0182(95)00004-6.

Willis KJ, van Andel TH: Trees or no trees? the environments of central and eastern Europe during the Last Glaciation. Quat Sc Rev. 2004, 23: 2369-2387. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.06.002.

Sümegi P, Rudner ZE: In situ charcoal fragments as remains of natural wild fires in the upper Würm of the Carpathian Basin. Quat Internat. 2001, 76/77: 165-176. 10.1016/S1040-6182(00)00100-2.

Coope GR: Interpretation of Quaternary insect fossils. Annu Rev Entomol. 1970, 15: 97-120. 10.1146/annurev.en.15.010170.000525.

Coope GR: Constancy of insect species versus inconstancy of Quaternary environments. Diversity of insect faunas. Edited by: Mound LA, Waloff N. 1978, Oxford, Blackwell, 176-187.

Coope GR: The response of insect faunas to glacial-interglacial climatic fluctuations. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1994, 344: 19-26. 10.1098/rstb.1994.0046.

Pazonyi P: Mammalian ecosystem dynamics in the Carpathian Basin during the last 27,000 years. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimat Palaeoecol. 2004, 212: 295-314. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.06.008.

Hertelendy E, Sümegi P, Szöör G: Geochronological and paleoclimatic characterisation of Quaternary sediments in the Great Hungarian Plain. Radiocarbon. 1992, 34: 833-839.

Füköh L, Krolopp E, Sümegi P: Quaternary malacostratigraphy in Hungary. Malacol Newsletter. 1995, 1 (Supplement): 1-219.

Sümegi P, Krolopp E: Quatermalocological analyses for modelling the Upper Weichselian palaeoenvironmental changes in the Carpathian basin. Quat Internat. 2002, 91: 53-63. 10.1016/S1040-6182(01)00102-1.

Schmitt T, Seitz A: Intraspecific allozymatic differentiation reveals the glacial refugia and the postglacial expansions of European Erebia medusa (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Biol J Linn Soc. 2001, 74: 429-458. 10.1006/bijl.2001.0584.

Deffontaine V, Libois R, Kotlík P, Sommer R, Nieberding C, Paradis E, Searle JB, Michaux JR: Beyond the Mediterranean peninsulas: evidence of central European glacial refugia for a temperate forest mammal species, the bank vole (Clethrionomys glareolus). Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 1727-1739. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02506.x.

Nieberding C, Libois R, Douady CJ, Morand S, Michaux JR: Phylogeography of a nematode (Heligmosomoides polygyrus) in the western Palearctic region: persistence of northern cryptic populations during ice ages?. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 765-779. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02440.x.

Pinceel J, Jordaens K, Pfenninger M, Backeljau T: Rangewide phylogeography of a terrestrial slug in Europe: evidence for Alpine refugia and rapid colonization after the Pleistocene glaciations. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 1133-1150. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02479.x.

Müller P: Biogeographie. 1980, Stuttgart, UTB, Eugen Ulmer

Schmitt T, Seitz A: Allozyme variation in Polyommatus coridon (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae): identification of ice-age refugia and reconstruction of post-glacial expansion. J Biogeogr. 2001, 28: 1129-1136. 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00621.x.

Schmitt T, Varga Z, Seitz A: Are Polyommatus hispana and Polyommatus slovacus bivoltine Polyommatus coridon (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)? – The discriminatory value of genetics in the taxonomy. Org Divers Evol. 2005, 5: 297-307. 10.1016/j.ode.2005.01.001.

Habel JC, Schmitt T, Müller P: The fourth paradigm pattern of postglacial range expansion of European terrestrial species: the phylogeography of the Marbled White butterfly (Satyrinae, Lepidoptera). J Biogeogr. 2005, 32: 1489-1497.

Schmitt T, Seitz A: Influence of the ice-age on the genetics and intraspecific differentiation of butterflies. Proc EIS, Macevol Priory. 2001, 16-26.

Schmitt T, Röber S, Seitz A: Is the last glaciation the only relevant event for the present genetic population structure of the Meadow Brown butterfly Maniola jurtina (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)?. Biol J Linn Soc. 2005, 85: 419-431. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00504.x.

Thomson G: Enzyme variation at morphological boundaries in Maniola and related genera (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Satyrinae). PhD thesis. 1987, University of Stirling, Scotland

Schmitt T, Gießl A, Seitz A: Did Polyommatus icarus (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) have distinct glacial refugia in southern Europe? – Evidence from population genetics. Biol J Linn Soc. 2003, 80: 529-538. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00261.x.

Henriksen HJ, Kreutzer IB: The butterflies of Scandinaviain Nature. 1982, Odense, Skandinavisk

Lukhtanov V, Lukhtanov A: Die Tagfalter Nordwestasiens. 1994, Herbipoliana 3, Marktleuthen, Eitschberger

Reinig W: Chorologische Voraussetzungen für die Analyse von Formenkreisen. Syllegomena Biologica, Festschrift für O. Kleinschmidt. 1950, 364-378.

Plötner J: Genetic diversity in mitochondrial 12S rDNA of western Palearctic water frogs (Anura, Ranidae) and implications for their systematics. J Zool Syst Evol Res. 1998, 36: 191-201.

Arntzen JW, García-París M: Morphological and allozyme studies of midwife toads (genus Alytes), including the description of two new taxa from Spain. Contr Zool. 1995, 65: 5-34.

García-París M, Jockusch EL: A mitochondrial DNA perspective on the evolution of Iberian Discoglossus (Amphibia: Anura). J Zool. 1999, 248: 209-218.

Steinfartz S, Veith M, Tautz D: Mitochondrial sequence analysis of Salamandra taxa suggests old splits of major lineages and postglacial recolonization of Central Europe from distinct source populations of S. salamandra. Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 397-410. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00870.x.

García-París M, Alcobendas M, Buckley M, Wake DB: Dispersal of viviparity across contact zones in iberian populations of fire salamanders (Salamandra) inferred from discordance of genetic and morphological traits. Evolution. 2003, 57: 129-143. 10.1554/0014-3820(2003)057[0129:DOVACZ]2.0.CO;2.

Carranza S, Arnold EN: History of west Mediterranean newts, Pleurodeles (Amphibia: Salamandridae), inferred from old and recent DNA sequences. Syst Biodiv. 2004, 1: 327-337. 10.1017/S1477200003001221.

Carranza S, Wade E: Taxonomic revision of Algero-Tunisian Pleurodeles (Caudata: Salamandridae) using molecular and morphological data. Revalidation of the taxon Pleurodeles nebulosus (Guichenot, 1850). Zootaxa. 2004, 488: 1-24.

Fromhage L, Vences M, Veith M: Testing alternative vicariance scenarios in Western Mediterranean discoglossid frogs. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004, 31: 308-322. 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.009.

Martínez-Solano I: Phylogeography of Iberian Discoglossus (Anura: Discoglossidae). J Zool Syst Evol Res. 2004, 42: 223-233. 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00249.x.

Martínez-Solano I, Goncalves HA, Arntzen JW, García-París M: Phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of midwife toads (Discoglossidae: Alytes). J Biogeogr. 2004, 31: 603-618.

Hsü KJ, Montadert L, Bernoulli D, Bianca CM, Erickson A, Garrison RE, Kidd RB, Mèliéres F, Müller C, Wright R: History of the Mediterranean Salinity Crisis. Nature. 1977, 267: 399-403. 10.1038/267399a0.

Hsü KJ: The Mediterranean was a desert. 1983, Princeton, Princeton University Press

Krijgsman W, Hilgen FJ, Raffi I, Sierro FJ, Wilson DS: Chronology, causes and progression of the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature. 1999, 400: 652-655. 10.1038/23231.

Duggen S, Hoernle K, van den Bogaard P, Rupke L, Morgan JP: Deep roots of the Messinian salinity crisis. Nature. 2003, 422: 602-606. 10.1038/nature01553.

Carranza S, Harris DJ, Arnold EN, Batista V, Gonzalez de la Vega JP: Phylogeography of the lacertid lizard, Psammodromus algirus, in Iberia and across the Strait of Gibraltar. J Biogeogr. 2006, 33: 1279-1288. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01491.x.

Carranza S, Arnold EN, Wade E, Fahd S: Phylogeography of the false smooth snakes, Macroptodon (Serpentes, Colubridae): mitochondrial DNA sequences show European populations arrived recently from Northwest Africa. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004, 33: 523-532. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.07.009.

Carranza S, Arnold EN, Pleguezuelos JM: Phylogeny, biogeography, and evolution of two Mediterranean snakes, Malpolon monspessulanus and Hemorrhois hippocrepis (Squamata, Colubridae), using mtDNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 40: 532-546. 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.03.028.

Lenk P, Fritz U, Joger U, Winks M: Mitochondrial phylogeography of the European pond turtle, Emys orbicularis (Linnaeus 1758). Mol Ecol. 1999, 8: 1911-1922. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00791.x.

Fritz U, Barata M, Busack SD, Fritsch G, Castilho R: Impact of mountain chains, sea straits and peripheral populations on genetic and taxonomic structure of a freshwater turtle, Mauremys leprosa (Reptilia, Testudines, Geoemydidae). Zool Sc. 2006, 35: 97-108. 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2005.00218.x.

Álvarez Y, Mateo JA, Andreu AC, Díaz-Paniagua C, Díez A, Bautista JM: Mitochondrial DNA haplotyping of Testudo greca on both continental sides of the Strait of Gibraltar. J Hered. 2000, 91: 39-41. 10.1093/jhered/91.1.39.

Paulo OS, Pinto I, Bruford MW, Jordan WC, Nichols RA: The double origin of Iberian peninsular chameleons. Biol J Linn Soc. 2002, 75: 1-7. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00002.x.

Horn A, Roux-Morabito G, Lieutier F, Kerdelhue C: Phylogeographic structure and past history of the circum-Mediterranean species Tomicus destruens Woll. (Coleoptera: Scolytinae). Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 1603-1615. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02872.x.

Busack SD: Biogeographic analysis of the herpetofauna separated by the formation of the Strait of Gibraltar. Natl Geogr Res. 1986, 2: 17-36.

Harris DJ, Carranza S, Arnold EN, Pinho C, Ferrand N: Complex biogeographical distribution of genetic variation within Podarcis Wall lizards across the Strait of Gibraltar. J Biogeogr. 2002, 29: 1-6. 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2002.00744.x.

Batista V, Harris DJ, Carretero MA: Genetic variation in Pleurodeles waltl Michaelles, 1830 (Amphibia: Salamandridae) across the strait of Gibraltar derived from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Herpetozoa. 2004, 16: 166-168.

Harris DJ, Batista V, Carretero MA, Ferrand N: Genetic variation in Tarentola mauritanica (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) across the Strait of Gibraltar derived from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. Amphibia-Reptilia. 2004, 25: 451-459. 10.1163/1568538041231229.

Harris DJ, Batista V, Lymberakis P, Carretero MA: Complex estimates of evolutionary relationships in Tarentola mauretanica (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) derived from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004, 30: 855-859. 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00260-4.

Busack SD, Lawson R, Wendy MA: Mitochondrial DNA, allozymes, morphology and historical biogeography in the Podarcis vaucheri (Lacertidae) species complex. Amphibia-Reptilia. 2005, 26: 239-256. 10.1163/1568538054253438.

Cosson JF, Hutterer R, Libois R, Sarà M, Taberlet P, Vogel P: Phylogeographical footprints of the Strait of Gibraltar and Quaternary climatic fluctuations in the western Mediterranean: a case study with the greater white-toothed shrew, Crocidura russula (Mammalia: Soricidae). Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 1151-1162. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02476.x.

Schmitt T, Seitz A: Low diversity but high differentiation: the population genetics of Aglaope infausta (Zygaenidae: Lepidoptera). J Biogeogr. 2004, 31: 137-144. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01079.x.

Harris DJ, Batista V, Carretero MA: Assessment of genetic diversity within Acanthodactylus erythrurus (Reptilia: Lacertidae) in Morocco and the Iberian Peninsula using mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Amphibia-Reptilia. 2004, 25: 227-232. 10.1163/1568538041231229.

Herterich K: Modelling the palaeo-climate. Klimageschichtliche Probleme der letzten 130 000 Jahre. Edited by: Frenzel B. 1991, Stuttgart, Fischer, 153-164.

Paulo OS, Dias C, Bruford MW, Jordan WC, Nichols RA: The persistence of Pliocene populations though the Pleistocene climatic cycles: evidence from the phylogeography of an Iberian lizard. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2001, 268: 1625-1630. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1706.

Gómez-Zurita J, Petitpierre E, Juan C: Nested cladistic analysis, phylogeography and speciation in the Timarcha goettingensis complex (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 557-570. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00900.x.

Gómez-Zurita J, Vogler AP: Incongruent nuclear and mitochondrial phylogeographic patterns in the Timarcha goettingensis species complex (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae). J Evol Biol. 2003, 16: 833-843. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00599.x.

Harris DJ, Sa-Sousa P: Molecular phylogenetics of Iberian wall lizards (Podarcis): is Podarcis hispanica a species complex?. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2002, 23: 75-81. 10.1006/mpev.2001.1079.

Mesquita N, Hänfling B, Carvalho R, Coelho MM: Phylogeography of the cyprinid Squalius aradensis and implications for conservation of the endemic freshwater fauna of southern Portugal. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 1939-1954. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02569.x.

Robalo JI, Santos CS, Almada VC, Doadrio I: Paleobiogeography of two Iberian endemic cyprinid fishes (Chondrostoma arcasii-Chondrostoma nacrolepidotus) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. J Hered. 2006, 97: 143-149. 10.1093/jhered/esj025.

Martínez-Solano I, Teixeira J, Buckley D, García-París M: Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of Lissotriton boscai (Caudata, Salamandridae): evidence for old, multiple refugia in an Iberian endemic. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 3375-3388. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03013.x.

Alexandrino J, Froufe E, Arntzen JW, Ferrand N: Genetic subdivision, glacial refugia and postglacial recolonization in the golden-striped salamander, Chioglossa lusitanica (Amphibia: Urodela). Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 771-781. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00931.x.

Alexandrino J, Arntzen JW, Ferrand N: Nested clade analysis and the genetic evidence for population expansion in the phylogeography on the golden-striped salamander, Chioglossa lusitanica (Amphibia: Urodela). Heredity. 2002, 88: 66-74. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800010.

Canestrelli D, Cimmaruta R, Costantini V, Nascetti G: Genetic diversity and phylogeography of the Apennine yellow-bellied toad Bombina pachypus, with implications for conservation. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 3741-3754. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03055.x.

Podnar M, Mayer W, Tvrtkovic N: Phylogeography of the Italian wall lizard, Podarcis sicula, as revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 575-588. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02427.x.

Seddon JM, Santucci F, Reeve NJ, Hewitt GM: DNA footprints of European hedgehogs, Erinaceus europaeus and E. concolor. Pleistocene refugia, postglacial expansion and colonization routes. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 2187-2198. 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01357.x.

Cooper SJ, Ibrahim KM, Hewitt GM: Postglacial expansion and genome subdivision in the European grasshopper Chorthippus parallelus. Mol Ecol. 1995, 4: 49-60.

Franck P, Garnery L, Celebrano G, Solignac M, Cornuet J-M: Hybrid origins of honeybees from Italy (Apis mellifera ligustica) and Sicily (A. m. sicula). Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 907-921. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00945.x.

Ursenbacher S, Conelli A, Golay P, Monney J-C, Zuffi MAL, Thiery G, Durand T, Fumagalli L: Phylogeography of the asp viper (Vipera aspis) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data: Evidence for multiple Mediterranean refugial areas. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006, 38: 546-552. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.08.004.

Seddon JM, Santucci F, Reeve NJ, Hewitt GM: Caucasus Mountains divide postulated postglacial colonization routes in the white-breasted hedgehog, Erinaceus concolor. J Evol Biol. 2002, 15: 463-467. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00408.x.

Marmi J, López-Giráldez F, Macdonald DW, Calafell F, Zholnerovskaya E, Domingo-Roura X: Mitochondrial DNA reveals a strong phylogeographic structure in the badger across Eurasia. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 1007-1020.

Szymura JM, Uzzell T, Spolsky C: Mitochondrial DNA variation in the hybridizing fire-bellied toads, Bombina bombina and B. variegata. Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 891-899. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00944.x.

Schmitt T, Habel JC, Zimmermann M, Müller P: Genetic differentiation of the Marbled White butterfly, Melanargia galathea, accounts for glacial distribution patterns and postglacial range expansion in southeastern Europe. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 1889-1901. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02900.x.

Dermitzakis DM, Papanikolaou DJ: Palaeogeography and geodynamics of the Aegean region during the Neogene. Ann Géol Pays Hellénique. 1981, 30: 245-289.

Parmakelis A, Stathi I, Spanos L, Louis C, Mylonas M: Phylogeography of Iurus dufoureius (Brullé, 1832) (Scorpiones, Iuridae). J Biogeogr. 2006, 33: 251-260. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01386.x.

Parmakelis A, Stathi I, Chatzaki M, Simaiakis S, Spanos L, Louis C, Mylonas M: Evolution of Mesobuthus gibbosus (Brullé, 1832) (Scorpiones: Buthidae) in the northeastern Mediterranean region. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 2883-2894.

Poulakakis N, Lymberakis P, Antoniou A, Chalkia D, Zouros E, Mylonas M, Valakos E: Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the wall-lizard Podarcis erhardii (Squamata: Lacertidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 28: 38-46. 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00037-X.

Poulakakis N, Lymberakis P, Valakos E, Zouros E, Mylonas M: Phylogeographic relationships and biogeography of Podarcis species from the Balkan Peninsula, by bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2005, 37: 845-857. 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.06.005.

Douris V, Cameron RAD, Rodakis GC, Lecanidou R: Mitochondrial phylogeography of the land snail Albinaria in Crete: long-term geological and short-term vicariance effects. Evolution. 1998, 52: 116-125. 10.2307/2410926.

Parmakelis A, Pfenninger I, Spanos L, Papagiannakis G, Louis C, Mylonas M: Inference of a radiation in Mastus (Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Enidae) on the island of Crete. Evolution. 2005, 59: 991-1005. 10.1554/04-489.

Santucci F, Emerson B, Hewitt GM: Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of European hedgehogs. Mol Ecol. 1998, 7: 1163-1172. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00436.x.

Taberlet P, Bouvet J: Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism, phylogeography, and conservation genetics of the brown bear (Ursus arctos) in Europe. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1994, 255: 195-200. 10.1098/rspb.1994.0028.

Dumolin-Lapègue S, Demesure B, Fineschi S, le Corre V, Petit RJ: Phylogeographic structure of white oaks throughout the European continent. Genetics. 1997, 146: 1475-1487.

Konnert M, Bergmann F: The geographical distribution of genetic variation of silver fir (Abies alba, Pinaceae) in relation to its migration history. Plant Syst Evol. 1995, 196: 19-30. 10.1007/BF00985333.

Bourset P, Auffrey JC, Britton-Davidian J, Bonhomme F: The evolution of the House Mice. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1993, 24: 119-152. 10.1146/annurev.es.24.110193.001003.

Taberlet P, Fumagalli L, Hausser J: Chromosomal versus mitochondrial DNA evolution: tracking the evolutionary history of the southwestern European populations of the Sorex araneus group (Mammalia, Insectivora). Evolution. 1994, 48: 623-636. 10.2307/2410474.

Fumagalli L, Hausser J, Taberlet P, Gielly L, Steward DT: Phylogenetic structure of the Holarctic Sorex araneus group and its relationship with S. samniticus, as inferred from mtDNA sequences. Hereditas. 1996, 125: 191-199. 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1996.00191.x.

King RA, Ferris C: Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. Mol Ecol. 1998, 7: 1151-1161. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00432.x.

Demesure B, Comps B, Petit RJ: Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of the common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Europe. Evolution. 1996, 50: 2515-1520. 10.2307/2410719.

Wallis GP, Arntzen JW: Mitochondrial-DNA variation in the crested newt superspecies: limited cytoplasmic gene flow among species. Evolution. 1989, 43: 88-104. 10.2307/2409166.

Ibrahim KM, Nichols RA, Hewitt GM: Spatial patterns of genetic variation generated by different forms of dispersal during range expansion. Heredity. 1996, 77: 282-291. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6880320.

Geiger H, Shapiro AM: Genetics, systematics and evolution of holarctic Pieris napi species group populations (Lepidoptera, Pieridae). Zeitschr Zool Syst Evolutionsf. 1992, 30: 100-122.

Porter AH, Geiger H: Limitations to the inference of gene flow at regional geographic scales – an example from the Pieris napi group (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in Europe. Biol J Linn Soc. 1995, 54: 329-348. 10.1016/0024-4066(95)90014-4.

Vandewoestijne S, Nève G, Baguette M: Spatial and temporal population genetic structure of the butterfly Aglais urticae L. (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae). Mol Ecol. 1999, 8: 1539-1543. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00725.x.

Highton R, Webster TP: Geographic protein variation and divergence in populations of the salamander Plethodon cinereus. Evolution. 1976, 30: 33-45. 10.2307/2407670.

Schwaegerle KE, Schaal BA: Genetic variability and founder effect in the pitcher plant Sarracenia purpurea. Evolution. 1979, 33: 1210-1218. 10.2307/2407479.

Johnson MS: Founder effects and geographic variation in the land snail Theba pisana. J Hered. 1988, 61: 133-142.

Stone GN, Sunnucks P: Genetic consequences of an invasion through a patchy environment – the cynipid gallwasp Andricus quercuscalicis (Hymenoptera: Cynipidae). Mol Ecol. 1993, 2: 251-268.

Assmann T, Nolte O, Reuter H: Postglacial colonization of middle Europe by Carabus auronitens as revealed by population genetics (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Carabid Beetles: Ecology and Evolution. Edited by: Desender K, Dufrêne M, Loreau M, Luff M, Maelfait J-P. 1994, Dordrecht, Kluwer, 3-9.

Demesure B, Comps B, Petit RJ: Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of the common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Europe. Evolution. 1996, 50: 2515-1520. 10.2307/2410719.

Dumolin-Lapègue S, Demesure B, Fineschi S, le Corre V, Petit RJ: Phylogeographic structure of white oaks throughout the European continent. Genetics. 1997, 146: 1475-1487.

Beebee TJC, Rowe G: Microsatellite analysis of natterjack toad Bufo calamita Laurenti populations: consequences of dispersal from a Pleistocene refugium. Biol J Linn Soc. 1999, 69: 367-381. 10.1006/bijl.1999.0368.

Schmitt T, Seitz A: Postglacial distribution area expansion of Polyommatus coridon (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) from its Ponto-Mediterranean glacial refugium. Heredity. 2002, 89: 20-26. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800087.

Schmitt T, Gießl A, Seitz A: Postglacial colonisation of western Central Europe by Polyommatus coridon (Poda 1761) (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae): evidence from population genetics. Heredity. 2002, 88: 26-34. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800003.

Ebert G, Rennwald E, (eds): Die Schmetterlinge Baden-Württembergs, Vol. 1 and 2. 1991, Stuttgart, Ulmer

Asher J, Warren M, Fox R, Harding P, Jeffcoate G, Jeffcoate S: The millennium atlas of butterflies in Britain and Ireland. 2001, Oxford, Oxford University Press

Schmitt T, Müller P: Limited hybridization along a large contact zone between two genetic lineages of the butterfly Erebia medusa (Satyrinae, Lepidoptera) in Central Europe. J Zool Syst Evol Res. 2007, 45: 39-46. 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00404.x.

Steward JR, Lister AM: Cryptic northern refugia and the origins of the modern biota. Trends Ecol Evol. 2001, 16: 608-613. 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02338-2.

Ursenbacher S, Carlsson M, Helfer V, Tegelström H, Fumagalli L: Phylogeography and Pleistocene refugia of the adder (Vipera berus) as inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 3425-3437. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03031.x.

Rafinki J, Babik W: Genetic differentiation among northern and southern populations of the moor frog Rana arvalis Nilsson in central Europe. Heredity. 2000, 84: 610-618. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00707.x.

Babik W, Branicki W, Sandera M, Litvinchuk S, Borkin LJ, Irwin JT, Rafinki J: Mitochondrial phylogeography of the moor frog, Rana arvalis. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 1469-1480. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02157.x.

Englbrecht CC, Freyhof J, Nolte A, Rassmann K, Schliewen U, Tautz D: Phylogeography of the bullhead Cottus gobio (Pisces: Teleostei: Cottidae) suggest a pre-Pleistocene origin of the major central European populations. Mol Ecol. 2000, 9: 709-722. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.00912.x.

Fink S, Excoffier L, Heckel G: Mitochondrial gene diversity in the common vole Microtus arvalis shaped by historical divergence and local adaptations. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 3501-3514. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02351.x.

Jaarola M, Searle JB: Phylogeography of field voles (Microtus agrestis) in Eurasia inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2613-2621. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01639.x.

Goropashnaya AV, Fedorov VB, Seifert B, Pamilo P: Limited phylogeographical structure across Eurasia in two red wood ant species Formica pratensis and F. lugubris (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 1849-1858. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02189.x.

Schmitt T, Rákosy L, Abadjiev S, Müller P: Multiple differentiation centres of a non-Mediterranean butterfly species in south-eastern Europe. J Biogeogr. 2007,

Korschunov J, Gorbunov P: Dnevnye babotschki asiatskoij tschasti Roussii. 1995, Jekaterinburg, Spravotschnik

Saint Girons H: Biogéographie et évolution des vipères européennes. C R Séances Soc Biogéogr. 1980, 496: 146-172.

Napolitano M, Descimon H: Genetic structure of French populations of the mountain butterfly Parnassius mnemosyne L. (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Biol J Linn Soc. 1994, 53: 325-344. 10.1006/bijl.1994.1075.

Meglécz E, Pecsenye K, Peregovits L, Varga Z: Allozymevariation in Parnassius mnemosyne (L.) (Lepidoptera) populations in North-East Hungary: variation within a subspecies group. Genetica. 1997, 101: 59-66. 10.1023/A:1018368622549.

Oshida T, Abramov A, Yanagawa H, Masuda R: Phylogeography of the Russian flying squirrel (Pteromys volans): implication of refugia theory in arboreal small mammal of Eurasia. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 1191-1196. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02475.x.

Uimaniemi L, Orell M, Mönkkönen M, Huhta E, Jokimäki J, Lumme J: Genetic diversity in the Siberian jay Perisoreus infaustus in fragmented old-growth forests of Fennoscandia. Ecography. 2000, 23: 669-677. 10.1034/j.1600-0587.2000.230604.x.

Cassel A, Tammaru T: Allozyme variability in central, peripheral and isolated populations of the scarce heath (Coenonympha hero : Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae); implications for conservation. Cons Gen. 2003, 4: 83-93. 10.1023/A:1021884832122.

Abbott RJ, Smith LC, Milne RI, Crawford RMM, Wolff K, Balfour J: Molecular analysis of plant migration and refugia in the arctic. Science. 2000, 289: 1343-1346. 10.1126/science.289.5483.1343.

Abbott RJ, Brochmann C: History and evolution of the arctic flora: In the footsteps of Eric Hultén. Mol Ecol. 2003, 12: 299-313. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01731.x.

Hultén E, Fries M: Atlas of North European vascular plants north of the Tropic of Cancer 1–3. 1986, Königstein: Koeltz Scientific Books

Schönswetter P, Stehlik I, Holderegger R, Tribsch A: Molecular evidence for glacial refugia of mountain plants in the European Alps. Mol Ecol. 2005, 14: 3547-3555. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02683.x.

Skrede I, Bronken Eidesen P, Pineiro Portela R, Brochmann C: Refugia, differentiation and postglacial migration in arctic-alpine Eurasia, exemplified by the mountain avens (Dryas octopetala L.). Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 1827-1840. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02908.x.

Schönswetter P, Popp M, Brochmann C: Rare arctic-alpine plants of the European Alps have different immigration histories: the snow bed species Minuartia biflora and Ranunculus pygmaeus. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 709-720. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02821.x.

Muster C, Berendonk TU: Divergence and diversity: lessens from arctic-alpine distribution (Pardosa saltuaria group, Lycosidae). Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 2921-2933.

Schönswetter P, Paun O, Tribsch A, Nikfeld H: Out of the Alps: colonization of Northern Europe by East Alpine populations of the glacier buttercup Ranunculus glacialis L. (Ranunculaceae). Mol Ecol. 2003, 12: 3373-3381. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01984.x.

Nève G: Dispersion chez une espèce à habitat fragmenté: Proclossiana eunomia (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae). PhD thesis. 1996, Université catholique de Louvain

Despres L, Loriot S, Gaudeul M: Geographic pattern of genetic variation in the European globeflower Trollius europaeus L. (Ranunculaceae) inferred from amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2337-2347. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01618.x.

Schmitt T, Hewitt GM: Molecular biogeography of the arctic-alpine disjunct burnet moth species Zygaena exulans (Zygaenidae, Lepidoptera) in the Pyrenees and Alps. J Biogeogr. 2004, 31: 885-893. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01079.x.

Bilton DT: Phylogeography and recent historical biogeography of Hydroporus glabriusculus Aubé (Coleoptera: Dytiscidae) in the British Isles and Scandinavia. Biol J Linn Soc. 1994, 51: 293-307. 10.1006/bijl.1994.1025.

Stehlik I, Schneller JJ, Bachmann K: Resistance or emigration: response of the high-alpine plant Eritrichium nanum (L.) Gaudin to the ice age within the Central Alps. Mol Ecol. 2001, 10: 357-370. 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2001.01179.x.

Kropf M, Kadereit JW, Comes HP: Late Quaternary distributional stasis in the submediterranean mountain plant Anthyllis montana L. (Fabaceae) inferred from ITS sequences and amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 447-463. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01446.x.

Schönswetter P, Tribsch A, Barfuss M, Nikfeld H: Several Pleistocene refugia detected in the high aline plant Phyteuma globulariifolium Sternb. & Hoppe (Campanulaceae) in the European Alps. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2637-2647. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01651.x.

Stehlik I: Resistance or emigration? Response of alpine plants to the ice ages. Taxon. 2003, 52: 499-510. 10.2307/3647448.

Stehlik I, Schneller JJ, Bachmann K: Immigration and in situ glacial survival of the low-alpine Erinus alpinus (Scrophulariaceae). Biol J Linn Soc. 2002, 77: 87-103. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00094.x.

Stehlik I, Blattne FR, Holderegger R, Bachmann K: Nunatak survival of the high alpine plant Eritrichium nanum (L.) Gaudin in the central Alps during the ice age. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2027-2036. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01595.x.

Tribsch A, Schönswetter P, Stuessy TF: Saponaria pumila (Caryophyllaceae) and the ice age in the European Alps. Amer J Bot. 2002, 89: 2024-2033.

Comes HP, Kadereit JW: Spatial and temporal patterns in the evolution of the flora of the European Alpine System. Taxon. 2003, 52: 451-462. 10.2307/3647445.

Kropf M, Kadereit JW, Comes HP: Differential cycles of range contraction and expansion in European high mountain plants during the Late Quaternary: insights from Pritzelago alpina (L.) O. Kuntze (Brassicaceae). Mol Ecol. 2003, 12: 931-949. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01781.x.

Schönswetter P, Tribsch A, Schneeweiss GM, Niklfeld H: Disjunction in relict alpine plants: phylogeography of Androsace brevis and A. wulfeniana (Primulaceae). Bot J Linn Soc. 2003, 141: 437-446. 10.1046/j.0024-4074.2002.00134.x.

Stehlik I: Glacial history of the alpine herb Rumex nivalis (Polygonaceae): a comparison of common phylogeographic methods with nested clade analysis. Amer J Bot. 2002, 89: 2007-2016.

Schönswetter P, Tribsch A, Stehlik I, Niklfeld H: Glacial history of high alpine Ranunculus glacialis (Ranunculaceae) in the European Alps in a comparative phylogeographical context. Biol J Linn Soc. 2004, 81: 183-195. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2003.00289.x.

Pauls SU, Lumbsch HT, Haase P: Phylogeography of themontane cadddisfly Drusus discolor : evidence for multiple refugia and periglacial survival. Mol Ecol. 2006, 15: 2153-2169. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.02916.x.

Schmitt T, Hewitt GM, Müller P: Disjunct distributions during glacial and interglacial periods in mountain butterflies: Erebia epiphron as an example. J Evol Biol. 2006, 19: 108-113. 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00980.x.

Holderegger R, Stehlik I, Abbott RJ: Molecular analysis of the Pleistocene history of Saxifraga oppositifolia in the Alps. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 1409-1418. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01548.x.

Martin J-F, Gilles A, Lörtscher M, Descimon H: Phylogenetics and differentiation among the western taxa of the Erebia tyndarus group (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). Biol J Linn Soc. 2002, 75: 319-332. 10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00022.x.

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Briscoe DA: Introduction to conservation genetics. 2002, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

Hansson B, Westerberg L: On the correlation between heterozygosity and fitness in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 2467-2474. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01644.x.

Reed DH, Frankham R: Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv Biol. 2003, 17: 230-237. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01236.x.

Schmitt T, Hewitt G: The genetic pattern of population threat and loss: a case study of butterflies. Mol Ecol. 2004, 13: 21-31. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2004.02020.x.

Taberlet P, Cheddadi R: Quaternary refugia and persistence of biodiversity. Science. 2002, 297: 2009-2010. 10.1126/science.297.5589.2009.

Hampe A, Petit RJ: Conserving biodiversity under climate change: the rear edge matters. Ecol Letters. 2005, 8: 461-467. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00739.x.

Schmitt T, Krauss J: Reconstruction of the colonization route from glacial refugium to the northern distribution range of the European butterfly Polyommatus coridon (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Diversity Distrib. 2004, 10: 271-274. 10.1111/j.1366-9516.2004.00103.x.

Acknowledgements

I thank Desmond Kime (La Chapelle) for the correction of my English and two anonymous referees for their constructive remarks, which helped improve the manuscript considerably.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, T. Molecular biogeography of Europe: Pleistocene cycles and postglacial trends. Front Zool 4, 11 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-4-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-4-11