Abstract

Background

Semen and semen-derived amyloid fibrils boost HIV infection in vitro but their impact on sexual virus transmission in vivo is unknown. Here, we examined the effect of seminal plasma (SP) and semen-derived enhancer of virus infection (SEVI) on vaginal virus transmission in the SIV/rhesus macaque (Macacca mulatta) model.

Results

A total of 18 non-synchronized female rhesus macaques (six per group) were exposed intra-vaginally to increasing doses of the pathogenic SIVmac239 molecular clone in the presence or absence of SEVI and SP. Establishment of productive virus infection was assessed by measuring plasma viral RNA loads at weekly intervals. We found that the first infections occurred at lower viral doses in the presence of SP and SEVI compared to the control group. Furthermore, the average peak viral loads during acute infection were about 6-fold higher after exposure to SP- and SEVI-treated virus. Overall infection rates after a total of 27 intra-vaginal exposures to increasing doses of SIV, however, were similar in the absence (4 of 6 animals) and presence of SP (5 of 6), or SEVI (4 of 6). Furthermore, the infectious viral doses required for infection varied considerably and did not differ significantly between these three groups.

Conclusions

Semen and SEVI did not have drastic effects on vaginal SIV transmission in the present experimental setting but may facilitate spreading of virus infection after exposure to low viral doses that most closely approximate the in vivo situation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite global efforts to limit the expansion of the AIDS pandemic, HIV-1 still causes about 2.3 million new infections each year. Most of these HIV-1 transmissions result from vaginal exposure to virus-containing semen during sexual intercourse [1–3]. Despite this dramatic spread of HIV-1, however, the efficiency of male-to-female intra-vaginal transmission is surprisingly low, with only about 1 event per 200 to 10,000 coital acts [4, 5]. Thus, the poor transmissibility of HIV-1 clearly restricts the spread of the AIDS pandemic.

In addition to viral loads, the type of sexual practice, and the presence of other sexually transmitted diseases, factors modulating the infectiousness of HIV-1 in genital fluids may play a key role in the efficacy of sexual transmission of HIV-1 [6–8]. Multiple studies reported that semen boosts HIV-1 infection in vitro[9–17]. This enhancing effect correlates with the levels of amyloidogenic fragments of prostatic acid phosphatase and semenogelins that are abundant in human semen [12, 13]. These semen-derived peptides rapidly form amyloid fibrils that facilitate virion attachment and may increase the infectiousness of HIV-1 in in vitro infection assays by several orders of magnitude [10–12]. Several agents that block this enhancing activity have been reported [14–18] and related fibril-forming peptides were developed for efficient lentiviral gene delivery [19]. Although semen is the main vector for the spread of HIV-1, its effect on sexual virus transmission in vivo is currently poorly understood.

Here, we used the SIV rhesus macaque non-human primate model [20, 21] to examine possible effects of semen and semen-derived amyloid fibrils on vaginal virus transmission. A total of 18 rhesus macaques (six per group) were exposed intra-vaginally to increasing doses of the pathogenic SIVmac239 molecular clone in the presence or absence of SEVI and seminal plasma. Productive virus infection was assessed by measuring plasma viral RNA loads at weekly intervals.

Results and discussion

To be able to use the same reagents throughout the entire in vivo study, we first generated large quantities of SIVmac stocks and SEVI solutions and collected pooled SP from healthy human donors. To ensure the efficacy of these reagents, we next examined the effect of SEVI and SP on the infectiousness of SIVmac and control HIV-1 stocks in vitro. We found that SP and SEVI enhanced infection by both HIV-1 and SIVmac, although the effects on the latter were substantially weaker (Figure 1A and B). SP was most effective at 10% (Figure 1A) since 50% begins to cause cytotoxic effects [10, 13]. In contrast, the enhancing effect of SEVI did not saturate (Figure 1B). In limiting dilution infection assays, performed as previously reported [10], treatment with SEVI enhanced the TCID50 of SIVmac up to 100-fold (Figure 1C), which is about two orders of magnitude lower than previously observed for HIV-1 [10].

SP and SEVI enhance SIVmac less effectively than HIV-1 infection. (A, B) Effect of the indicated doses of SP (A) and SEVI (B) on infection of TZM-bl cells by HIV-1 NL4-3 (blue) or SIVmac239 (red). The left panels show infection by both viruses and the right panels SIVmac239 only. (C) Limiting dilution analysis of SIVmac239. CEM-M7 cells were infected in triplicate with 10-fold dilutions of the SIVmac239 virus stock in the presence of the indicated concentrations of SEVI. Indicated is the number of cultures that became productively infected.

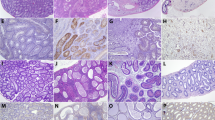

Since the effects of semen and SEVI on lentiviral infection have thus far almost exclusively been examined in human-derived cells [9–17], we next analyzed whether they can be confirmed in primary monkey cells. To assess possible differences in the susceptibility to SIV infection and the enhancing effects of SEVI or SP, we utilized PBMCs derived from all 18 animals assigned to the in vivo vaginal challenge study. We found that SEVI increased SIVmac239 infection of rhesus macaque PBMCs between 4.8- and 57.7-fold (Figure 2A), while SP-mediated enhancement ranged from 3.9- to 11.1-fold (Figure 2B). Notably, the absolute levels of SIVmac infection and the magnitudes of SEVI- and SP-mediated enhancement did not differ significantly between PBMCs derived from the three treatment groups of animals (Figure 2C and D).

Susceptibility of PBMCs derived from macaques assigned to the in vivo study to SIVmac239 infection and to SP- or SEVI-mediated enhancement of infection. (A, B) Effect of SEVI (A) and SP (B) on SIVmac239 infection of PBMCs derived from the 18 animals assigned to the in vivo study. PHA/IL-2 stimulated cells were infected with SIVmac239 encoding a luciferase reporter gene [22]. Numbers above the bars indicate n-fold infectivity enhancement observed in the presence of SP or SEVI compared to those measured in their absence. RLU/s: relative light units per second. (C, D) PBMCs were grouped based on their belonging to the control (co), SEVI or SP groups in the subsequent in vivo study. The box plots in C show the mean infection rates and 25th and 75th percentiles measured in the absence of SP and SEVI. The box plots in (D) show the n-fold enhancement of SIVmac239 infection of PBMCs derived from the three groups of macaques in the presence of SEVI (10 μg/ml) or SP (10% v/v).

Our results showed that SEVI and SP enhance HIV-1 infection substantially more efficiently than infection by SIVmac. Nonetheless, the impact on SIVmac infection was readily detectable and highly significant. Thus, we decided to proceed with the in vivo study, although the effects in the SIV/macaque model may not fully reflect the impact of semen and SEVI in vaginal transmission of HIV-1. To closely mimic the situation during sexual virus transmission we did not synchronize the menstrual cycle of the female macaques or treat them with agents to induce thinning of the vaginal layer. The animals were exposed to up to 27 weekly non-traumatic vaginal challenges with gradually increasing doses of virus stocks that were either mixed with solutions of SEVI or SP or PBS (Figure 3). The final concentrations were 35 μg/ml of SEVI and 90% (v/v) of SP, the former was the yield of amyloidogenic PAP fragments from human semen [10], while the latter approximates the 100% of semen that is transferred during sexual intercourse. We used human semen because the challenges required a total of ~300 ml of this body fluid, a quantity which cannot be obtained from macaques. Furthermore, we felt that examination of the genuine vector of sexual transmission of HIV-1 in humans may have higher relevance for the spread of the AIDS pandemic than utilization of semen from a monkey species that is not a natural host of primate lentiviruses. However, vaginal exposure of macaques to human semen may affect their susceptibility to SIV infection by inducing immune reactions to the foreign antigens and local inflammation. Both enhancing effects due to the recruitment of activated viral target cells to the sites of virus exposure and protective effects due to the induction of local innate immune responses are conceivable. Clearly, the induction of immune responses to human antigens is a potential confounding factor. Notably, however, insemination is also associated with the induction of immunological processes and lymphocyte activation in humans [23–25]. Thus, some effects induced by vaginal exposure of macaques to human semen may reflect the events during sexual transmission of HIV-1 in humans.

The susceptibility of the animals to SIVmac infection after vaginal exposure varied considerably within each treatment group. One macaque (15075) in the SP group already became infected after the second exposure to 100 TCID50 (Figure 3). This animal showed signs of a mild infection of the respiratory tract at the week after productive SIV infection. However, there were no hints of inflammatory bacterial or viral genital infections. Thus, there were no obvious reasons for an enhanced susceptibility of animal 15075 to SIV infection. In strict contrast, five of the 18 animals (two in the control and SEVI groups and one in the SP group) remained uninfected even after eight weekly exposures to 12,800 TCID50 (Figures 3 and 4A). One animal in the SEVI group (14825) showed high levels of viremia during acute infection but subsequently efficiently controlled virus replication (Figure 3). Furthermore, one macaque (14828) assigned to the group of uninfected animals showed viral blips after the last virus exposure but did not become systemically infected (Figure 3). On average, the doses required for vaginal SIVmac infection did not differ significantly between the three treatment groups (Figures 4B and C). However, the first infections occurred at lower doses in the SP (100 TCID50) and SEVI (1,600 TCID50) groups than in the control (3,200 TCID50) group (Figures 3, 4A). Furthermore, the peak viral loads during acute infection were on average about 6-fold higher in animals that received SEVI and SP treated virus stocks (Figure 4D). This difference reached significance when the SEVI/SP groups were combined (p = 0.0243). The significance of these differences in VLs and the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. It is tempting to speculate that weekly exposures to semen and seminal fibrils may enhance local inflammation [24–27] and that the resulting increase of activated viral target cells may facilitate initial virus spread. It has also been reported, however, that seminal fluid has immunosuppressive activity [28]. Thus, reduced innate immune control provides an alternative explanation for higher peak VLs after treatment with seminal plasma.

Infection of rhesus macaques after vaginal exposure to SP- and SEVI-treated SIVmac. (A) Proportion of infected animals in the three treatment groups as a function of the number of weekly vaginal exposures. (B) Administered viral dose (TCID50) leading to systemic infection and (C) total viral dose (cumulative TCID50) received by the animals until they became systemically infected. Two of the six macaques in the control and SEVI groups and one animal in the SP group are not shown since they remained uninfected after final virus exposure. (D) Peak viral loads during acute infection in the control, SEVI and SP groups.

Our finding that semen may promote virus infection and spread after exposure to very low viral doses is in agreement with the results of two earlier studies that also reported increased vaginal SIV infection of macaques in the presence of semen, but only under conditions of low viral inoculums [29, 30]. Finally, we found that polymorphisms in TRIM5α reported to affect the susceptibility to SIV infection [31] had no significant impact on the acquisition of SIVmac in the present study (Additional file 1: Figure S1). This is in agreement with the previous finding that the macaque adapted SIVmac239 strain is resistant against both wild-type and variant TRIM-5α alleles [31].

Due to the limited number of animals and their high variability in susceptibility to vaginal SIV infection, our study provides only very preliminary insights into the role of semen and SEVI in sexual transmission of HIV-1. Our finding that the effects of SP and SEVI are not as striking as in cell culture systems did not come as a surprise since attachment factors that increase the stickiness of viral particles may only promote intra-vaginal virus transmission in the presence of micro-lesions in the vaginal mucosal layer and at low viral doses (schematically outlined in Figure 5). In agreement with the findings of previous studies [29, 30], our results suggest that semen may increase the risk of vaginal transmission after exposure to low viral loads. Notably, even the repeated low dose challenge model utilizes viral quantities that are substantially higher than those transferred in humans because they usually achieve virus infection after about 10 to 20 challenges, whereas about 200 to 10,000 exposures are required for vaginal virus transmission by sexual intercourse. Furthermore, the effects of SEVI and SP on SIV infection in vitro were substantially weaker than those observed on HIV-1. Thus, the results of the present study may underestimate the effect of semen on the efficiency of HIV-1 transmission by sexual intercourse.

Schematic outline of the possible roles of viral dose and the presence of microlesions in the effect of seminal attachment factors on sexual transmission of SIV and HIV-1. Viral particles are indicated as black dots, mucus as pink line and the multi-layered vaginal epithelium by dashed lines. Infection of viral target T cells is indicated by the “+” symbol. Please note that this simplified model needs to be challenged in experimental studies.

Conclusions

In summary, our results show that SP and SEVI did not have drastic effects on vaginal SIV transmission in the present experimental settings, using non-synchronized macaques and increasing viral doses. However, SP and SEVI may facilitate spreading of virus infection after exposure to low viral doses that most closely approximate the in vivo situation. This study provides hints for the design of future animal studies of the effects of semen on the efficacy of sexual transmission of HIV-1. The effects of SP and SEVI on SIVmac239 infection in vitro were relatively weak compared to those previously observed for HIV-1. Notably, SIVmac239 was adapted to macaques through intravenous injections [32]. Thus, this molecular clone of SIV may not be well suited for studies on virus transmission via the genital mucosa. Currently, we are examining whether chimeric viral constructs (SHIVs) containing the HIV-1 Env glycoprotein may better reflect the full magnitude of the enhancing effects of semen and SEVI observed on HIV-1 infection. Furthermore, it is known that the phase of the menstrual cycle and different levels of vaginal inflammation, affect the susceptibility to HIV-1 and SIV infection [29, 33, 34]. Thus, consideration of the levels of pre-existing genital inflammation and/or rectal instead of vaginal exposure may deliver significant results with a reasonable number of animals. It would also circumvent biases due to menstrual cycle asynchrony, while the higher susceptibility associated with the presence of a single columnar layer of the rectal epithelium would reduce variations between donors. Such studies seem highly warranted since a better understanding of the role of semen and semen-derived amyloid fibrils in the spread of HIV-1 may be essential for the development of effective microbicides and vaccines.

Methods

Seminal plasma

Semen samples were collected at the “Kinderwunschzentrum” Ulm (Germany) from healthy individuals with informed consent. Pooled semen was generated from samples derived from > 20 individual donors. All ejaculates were allowed to liquefy for 30 min. SP represents the cell free supernatant of semen pelleted for 5 min at 10.000 rpm. In all experiments, aliquots were rapidly thawed and analyzed immediately.

Generation of SEVI

PAP248-286 was produced by standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis, purified by preparative RP HPLC and analyzed by HPLC and MS. Lyophilized synthetic peptides were suspended in serum-free DMEM at concentrations of 5 to 10 mg/ml. Fibril formation was induced by overnight agitation at 37 °C and 1400 rpm using an Eppendorf Thermomixer and verified by Congo Red staining or electron microscopy.

Virus stocks and infectivity

Virus stocks of HIV-1 NL4-3 and SIVmac239 were generated by transient transfection of 293 T cells as described [10].

Effect of SP and SEVI on virus infection in vitro

The effect of SP and SEVI on HIV-1 and SIVmac infection and limiting dilution infection analyses were performed using adherent TZM-bl reporter cells or CEM-M7 cells as described previously [10, 13].

Animals

The animals assigned to this study were mature female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of Chinese origin. These rhesus macaques were housed at the German Primate Center in accordance with the German Animal Welfare Act and in compliance with the European Union guidelines on the use of nonhuman primates for biomedical research. The study was approved by an ethics committee authorized by the Lower Saxony State Office for Consumer Protection and Food Safety.

Vaginal exposure

To examine possible effects of SP and SEVI on SIV transmission, rhesus macaques were exposed vaginally once a week for up to 28 weeks to the SIVmac239 molecular clone except for a gap between week 20 and 22. The viral application procedure had been described before [35]. The intra-vaginal viral exposures were performed using escalating doses, i.e. with 25 TCID50 for the first four applications, 100 TCID50 for the following four challenges, and 400 TCID50 for another four exposures. Thereafter, doses were doubled after every second week eventually reaching 12.800 TCID50 for the final eight inoculations (see also Figure 3). Challenges were stopped 1 week after viral RNA became detectable in plasma with levels >100 copy equivalents/ml, indicating systemic infection. To prepare the inocula, virus stocks were diluted to a concentration 10-fold above the desired dose and either diluted in PBS buffer only (control group), a SEVI dilution to achieve a final concentration of 35 μg/ml (SEVI group) or undiluted SP (90% v/v; SP group). Virus exposures were done by non-traumatic inoculation of 0.25 ml of untreated, SP- or SEVI-treated virus into the vaginal tract. All experiments were done under highly controlled conditions by the same personnel using the same virus stock and inoculum preparation procedure.

Viral RNA loads

Viral RNA copies were quantified in purified SIV RNA from plasma using TaqMan-based real-time PCR on an ABI-Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) as described [36].

Detection of TRIM5 polymorphisms

RNA was isolated from PBMCs using Qiagen RNAeasy Plus Minikit. RNA was reverse transcribed using Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Trim5α-sequences were amplified by PCR using primers Trim5-for 5′-AGTGGAGAAGCTGCTATGGCT −3′and Trim5-rev 5′-ATGGACAAGAGGTGCTGTACAC −3′. Amplified PCR fragments were cloned into pJET1.2 (CloneJET PCR cloning kit, Fermentas). DNA-sequences of up to 5 clones in homozygous macaques were determined using Big Dye Cycle Sequencing. Amplicons were analyzed on an ABI 3130xL Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems). Sequence comparison was done with the freely available program Bioedit. TRIMcyp detection was performed by analysis of PCR fragment length polymorphism essentially as described [31].

Data analysis

The PRISM package version 5.0 (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA) was used for all statistical calculations.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus type-1

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- SEVI:

-

Semen derived enhancer of viral infection

- SIVmac:

-

Simian immunodeficiency virus of rhesus macaques

- SP:

-

Seminal plasma

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- TCID50:

-

Median tissue culture infective dose

- RP-HPLC:

-

Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- MS:

-

Mass Spectrometry.

References

United Nations: UNAIDS 2013 report of the global AIDS epidemic. 2013, http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf,

Quinn TC, Overbaugh J: HIV/AIDS in women: an expanding epidemic. Science. 2005, 308: 1582-1583. 10.1126/science.1112489.

Royce RA, Sena A, Cates W, Cohen MS: Sexual transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1997, 336: 1072-1078. 10.1056/NEJM199704103361507.

Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, Lutalo T, Li X, van Cott T, Quinn TC, Rakai Project Team: Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001, 357: 1149-1153. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2.

Boily MC, Baggaley RF, Wang L, Masse B, White RG, Hayes RJ, Alary M: Heterosexual risk of HIV-1 infection per sexual act: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009, 9: 118-129. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70021-0.

Chakraborty H, Sen PK, Helms RW, Vernazza PL, Fiscus SA, Eron JJ, Patterson BK, Coombs RW, Krieger JN, Cohen MS: Viral burden in genital secretions determines male-to-female sexual transmission of HIV-1: a probabilistic empiric model. AIDS. 2001, 15: 621-627. 10.1097/00002030-200103300-00012.

Gupta P, Mellors J, Kingsley L, Riddler S, Singh MK, Schreiber S, Cronin M, Rinaldo CR: High viral load in semen of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected men at all stages of disease and its reduction by therapy with protease and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Virol. 1997, 71: 6271-6275.

Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, Vernazza PL, Leu SY, Stewart PW, Goh LE, Cohen MS, Quest Study: Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Inf Dis. 2004, 189: 1785-1792. 10.1086/386333.

Bouhlal H, Chomont N, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Kazatchkine MD, Belec L, Hocini H: Opsonization of HIV-1 by semen complement enhances infection of human epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2002, 169: 3301-3306.

Münch J, Rücker E, Ständker L, Adermann K, Goffinet C, Schindler M, Wildum S, Chinnadurai R, Rajan D, Specht A, Giménez-Gallego G, Sánchez PC, Fowler DM, Koulov A, Kelly JW, Mothes W, Grivel JC, Margolis L, Keppler OT, Forssmann WG, Kirchhoff F: Semen-derived amyloid fibrils drastically enhance HIV infection. Cell. 2007, 131: 1059-1071. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.014.

Arnold F, Schnell J, Zirafi O, Stürzel C, Meier C, Weil T, Ständker L, Forssmann WG, Roan NR, Greene WC, Kirchhoff F, Münch J: Naturally occurring fragments from two distinct regions of the prostatic acid phosphatase form amyloidogenic enhancers of HIV infection. J Virol. 2012, 86: 1244-1249. 10.1128/JVI.06121-11.

Roan NR, Müller JA, Liu H, Chu S, Arnold F, Stürzel CM, Walther P, Dong M, Witkowska HE, Kirchhoff F, Münch J, Greene WC: Peptides released by physiological cleavage of semen coagulum proteins form amyloids that enhance HIV infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2011, 10: 541-550. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.010.

Kim KA, Yolamanova M, Zirafi O, Roan NR, Staendker L, Forssmann WG, Burgener A, Dejucq-Rainsford N, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Greene WC, Kirchhoff F, Münch J: Semen-mediated enhancement of HIV infection is donor-dependent and correlates with the levels of SEVI. Retrovirology. 2010, 7: 55-10.1186/1742-4690-7-55.

Roan NR, Münch J, Arhel N, Mothes W, Neidleman J, Kobayashi A, Smith-McCune K, Kirchhoff F, Greene WC: The cationic properties of SEVI underlie its ability to enhance human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2009, 83: 73-80. 10.1128/JVI.01366-08.

Roan NR, Sowinski S, Munch J, Kirchhoff F, Greene WC: Aminoquinoline surfen inhibits the action of SEVI (semen-derived enhancer of viral infection). J Biol Chem. 2010, 285: 1861-1869. 10.1074/jbc.M109.066167.

Hauber I, Hohenberg H, Holstermann B, Hunstein W, Hauber J: The main green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate counteracts semen-mediated enhancement of HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 9033-9038. 10.1073/pnas.0811827106.

Olsen JS, Brown C, Capule CC, Rubinshtein M, Doran TM, Srivastava RK, Feng C, Nilsson BL, Yang J, Dewhurst S: Amyloid-binding small molecules efficiently block SEVI (semen-derived enhancer of virus infection)- and semen-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285: 35488-35496. 10.1074/jbc.M110.163659.

Sievers SA, Karanicolas J, Chang HW, Zhao A, Jiang L, Zirafi O, Stevens JT, Münch J, Baker D, Eisenberg D: Structure-based design of non-natural amino-acid inhibitors of amyloid fibril formation. Nature. 2011, 475: 96-100. 10.1038/nature10154.

Yolamanova M, Meier C, Shaytan AK, Vas V, Bertoncini CW, Arnold F, Zirafi O, Usmani SM, Müller JA, Sauter D, Goffinet C, Palesch D, Walther P, Roan NR, Geiger H, Lunov O, Simmet T, Bohne J, Schrezenmeier H, Schwarz K, Ständker L, Forssmann WG, Salvatella X, Khalatur PG, Khokhlov AR, Knowles TP, Weil T, Kirchhoff F, Münch J: Peptide nanofibrils boost retroviral gene transfer and provide a rapid means for concentrating viruses. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013, 8: 130-136. 10.1038/nnano.2012.248.

Haase AT: Targeting early infection to prevent HIV-1 mucosal transmission. Nature. 2010, 464: 217-223. 10.1038/nature08757.

Haase AT: Early events in sexual transmission of HIV and SIV and opportunities for interventions. Annu Rev Med. 2011, 62: 127-139. 10.1146/annurev-med-080709-124959.

Pöhlmann S, Lee B, Meister S, Krumbiegel M, Leslie G, Doms RW, Kirchhoff F: Simian immunodeficiency virus utilizes human and Sooty Mangabey but not Rhesus Macaque STRL33 for efficient entry. J Virol. 2000, 74: 5075-5082. 10.1128/JVI.74.11.5075-5082.2000.

Robertson SA, Ingman WV, O’Leary S, Sharkey DJ, Tremellen KP: Transforming growth factor beta–a mediator of immune deviation in seminal plasma. J Reprod Immunol. 2002, 57: 109-128. 10.1016/S0165-0378(02)00015-3.

Sharkey DJ, Macpherson AM, Tremellen KP, Robertson SA: Seminal plasma differentially regulates inflammatory cytokine gene expression in human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007, 13: 491-501. 10.1093/molehr/gam028.

Sharkey DJ, Tremellen KP, Jasper MJ, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Robertson SA: Seminal fluid induces leukocyte recruitment and cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in the human cervix after coitus. J Immunol. 2012, 188: 2445-2454. 10.4049/jimmunol.1102736.

Robertson SA: Seminal plasma and male factor signalling in the female reproductive tract. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 322: 43-52. 10.1007/s00441-005-1127-3.

Robertson SA, Sharkey DJ: The role of semen in induction of maternal immune tolerance to pregnancy. Semin Immunol. 2001, 13: 243-254. 10.1006/smim.2000.0320.

Clark GF, Schust DJ: Manifestations of immune tolerance in the human female reproductive tract. Front Immunol. 2013, 4: 26-

Neildez O, Le Grand R, Chéret A, Caufour P, Vaslin B, Matheux F, Théodoro F, Roques P, Dormont D: Variation in virological parameters and antibody responses in macaques after atraumatic vaginal exposure to a pathogenic primary isolate of SIVmac251. Res Virol. 1998, 149: 53-68. 10.1016/S0923-2516(97)86900-2.

Miller CJ, Marthas M, Torten J, Alexander NJ, Moore JP, Doncel GF, Hendrickx AG: Intravaginal inoculation of rhesus macaques with cell-free simian immunodeficiency virus results in persistent or transient viremia. J Virol. 1994, 68: 6391-6400.

Kirmaier A, Wu F, Newman RM, Hall LR, Morgan JS, O’Connor S, Marx PA, Meythaler M, Goldstein S, Buckler-White A, Kaur A, Hirsch VM, Johnson WE: TRIM5 suppresses cross-species transmission of a primate immunodeficiency virus and selects for emergence of resistant variants in the new species. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8 (8): e1000462-10.1371/journal.pbio.1000462.

Naidu YM, Kestler HW, Li Y, Butler CV, Silva DP, Schmidt DK, Troup CD, Sehgal PK, Sonigo P, Daniel MD, et al: Characterization of infectious molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) and human immunodeficiency virus type 2: persistent infection of rhesus monkeys with molecularly cloned SIVmac. J Virol. 1988, 62: 4691-4696.

Vishwanathan SA, Guenthner PC, Lin CY, Dobard C, Sharma S, Adams DR, Otten RA, Heneine W, Hendry RM, McNicholl JM, Kersh EN: High susceptibility to repeated, low-dose, vaginal SHIV exposure late in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle of pigtail macaques. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011, 57: 261-264. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318220ebd3.

Spear G, Rothaeulser K, Fritts L, Gillevet PM, Miller CJ: In captive rhesus macaques, cervicovaginal inflammation is common but not associated with the stable polymicrobial microbiome. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e52992-10.1371/journal.pone.0052992.

Stolte-Leeb N, Loddo R, Antimisiaris S, Schultheiss T, Sauermann U, Franz M, Mourtas S, Parsy C, Storer R, La Colla P, Stahl-Hennig C: Topical nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor MC 1220 partially prevents vaginal RT-SHIV infection of macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011, 27: 933-943. 10.1089/aid.2010.0339.

Negri DR, Baroncelli S, Catone S, Comini A, Michelini Z, Maggiorella MT, Sernicola L, Crostarosa F, Belli R, Mancini MG, Farcomeni S, Fagrouch Z, Ciccozzi M, Boros S, Liljestrom P, Norley S, Heeney J, Titti F: Protective efficacy of a multicomponent vector vaccine in cynomolgus monkeys after intrarectal simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. J Gen Virol. 2004, 85: 1191-1201. 10.1099/vir.0.79794-0.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicole Leuchte and Heidi Meyer for expert technical assistance and Nadia Roan and Warner C. Greene for critical reading and helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the DFG to JM and FK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JM and YM performed in vitro experiments; US, KR and CSH performed animal experiments; JM, CSH and FK conceived and designed the study; FK wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12977_2013_3638_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Susceptibility of rhesus macaques differing in their TRIM5 gene to infection by SIVmac239 after vaginal exposure. Animals that became infected after vaginal virus exposure were grouped based on the presence of homozygosity for TRIM5TFP allele (Wt, n = 5 of 7) or TRIM5∆∆Q (Del, n = 3 of 4) or heterozygous (Het, n = 4 of 6). TRIMCypA was absent in the macaques. Given are the numbers of animals that became infected out of the total number of macaques with the respective TRIM5 genotype. For one infected macaque the genotype could not be unambiguously determined. (A) Viral dose (TCID50) at the week before the animals became systemically infected. (B) Total viral dose (cumulative TCID50) inoculated into the animals until they became infected. (PDF 57 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Münch, J., Sauermann, U., Yolamanova, M. et al. Effect of semen and seminal amyloid on vaginal transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus. Retrovirology 10, 148 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-10-148

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-10-148