Abstract

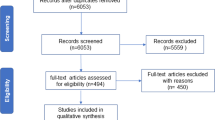

Although major depressive disorder imposes a serious public health burden and affects nearly one in six individuals in developed countries over their lifetimes, there is still no consensus on its pathophysiology. Inflammation and cytokines have emerged as a promising new avenue in depression research, and, in particular, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) has been shown to be significant in depression physiology. In this review we summarize current research on MIF and depression. We highlight the arguments for MIF as a pro- and antidepressant species and discuss the potential implications for therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a clinical syndrome defined by chronic disturbances in emotion and ideation that are accompanied by somatic or neurovegetative symptoms [1]. The disease has a worldwide lifetime prevalence of 12%, with the prevalence in developed countries (USA and Europe) as high as 18% [2]; this figure is increasing over time [3]. Additionally, depressive mood is often comorbid with other psychiatric conditions such as anxiety and eating disorders, as well as with chronic medical conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, and chronic inflammatory diseases [4]; this is often called ‘secondary depression’ [5]. Comorbid depression significantly worsens outcomes in coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and stroke [6, 7]. Depression can also cause cognitive symptoms [8] that can produce severe psychosocial deficits [9]. Despite these considerations, treatment for depression has not changed significantly in recent years. Current treatments do not adequately address cognitive deficits in depression [10], and there remain few solutions for treatment-resistant depression, which affects almost half of the patient population [11].

One of the reasons for the slow progress in this area is the lack of a unified theory of the pathobiology of depression. Several hypotheses are currently supported by research. One of the oldest is the monoamine theory, which asserts that depression is caused by a depletion of monoamines (such as serotonin or norepinephrine) in the brain [12]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) operate on this premise, and they are currently among the first-line treatments for major depression [13]. However, this theory fails to explain the delay in remission during treatment with SSRIs, or why depletion of monoamines does not reproduce depressive symptoms in healthy controls. As a result, a neurotrophic theory of depression has emerged: atrophic changes are found in the postmortem brains of MDD patients, and increases in neurogenesis or neuroplastic factors have antidepressant effects [12]. Any unified theory of depression would doubtless need to incorporate aspects of both of these hypotheses.

A large body of evidence has also pointed to an inflammatory etiology in depression [14]. Depressed mood develops in nearly a third of patients treated with recombinant interferon alpha, and is more prevalent in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases [15, 16]. Systemic inflammation produces sickness behavior that resembles depression in both patients and rodent models [17]. One of the challenges of this hypothesis is explaining how peripheral cytokines can cross the blood brain barrier and affect the central nervous system to induce depression. One proposed explanation centers on the cytokine-activated enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which has been shown to induce depression-like behavior. It degrades neural tryptophan into 3-hydroxykyurenin and quinolinic acid; in addition to being neurotoxic, these metabolites also drain local stores of tryptophan, which is a prerequisite in the synthesis of serotonin [18].

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

With mounting evidence for a role for cytokines in depression, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) has emerged as a strong candidate for a pathophysiological role. MIF is one of the first cytokines to be investigated, originally identified by its ability to prevent random migration of macrophages. It is released from intracellular pools by T- and B-lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and basophils. It is also widely distributed in tissues [19]. Its release is triggered when cells are exposed to microbial products, pro-inflammatory cytokines, or specific antigens. Upon release, it acts in an autocrine and paracrine fashion to induce production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [20]. It also opposes the anti-inflammatory activity of glucocorticoids [21], which will be discussed later. Finally, it has been shown to have a role in cellular responses to DNA damage and cell cycle regulation [22]. MIF has been implicated in several disease conditions, including sepsis [23], acute respiratory distress syndrome [24], tuberculosis [25], and diabetes [26].

MIF has been shown to bind the transmembrane receptor CD74 and complex with CD44, with subsequent signal transduction via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/ERK2), which are subtypes of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) [27]. This leads to several downstream effects that mediate the physiological effects of MIF. Particularly significant is the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Upregulation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) is likely important in both the pro-inflammatory cascade and inhibition of glucocorticoid activity [28]. MIF also increases expression of TLR4, which is involved in immune responses to pathogenic bacteria as well as the pathogenesis of endotoxemia [29]. In addition, MIF promotes survival of pro-inflammatory cells by inhibition of the tumor suppressor p53 [30]. MIF has been shown bind and inhibit JUN-activation domain-binding protein 1 (Jab1), a coactivator of activator protein 1 (AP1), which is involved in cell growth. MIF also acts as an enzyme in vitro, showing D-dopachrome tautomerase and thiol protein oxidoreductase activities [31, 32].

There are multiple lines of research pointing to a role for MIF in the pathobiology of depression. These findings have (i) identified MIF expression in the brain, particularly in areas significant to the behavioral symptoms of depression; (ii) established the significance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in depression, with which MIF has an intricate relationship; (iii) shown an interaction between MIF and both lifestyle and pharmacological antidepressant treatments; (iv) determined a connection between MIF and neurogenesis, another important avenue of depression research; and (v) explored MIF as a biomarker in major depression and other mood disorders. There is still much uncertainty about MIF’s exact pathophysiologic role, and whether its activity promotes or obstructs pathological processes in depression. The goal of this review is to summarize current research on the topic, highlight evidence for MIF as a pro- or antidepressant, and address the potential for future developments in this area.

MIF in the central nervous system

Although MIF was originally identified as a product of T-lymphocytes, it was later discovered to be ubiquitous, with especially high expression rates in epithelia and endocrine tissues [20]. Several studies have also highlighted MIF expression in the central nervous system (CNS). Immunostaining of bovine brain has established MIF expression in the subependymal astrocytes, CA3/CA4 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus, and granule cells of the dentate gyrus [33]. Similar techniques have been used to localize MIF expression in rat brain to choroid plexus epithelia, ventricular ependymal cells, and cerebral astrocytes; the presence of MIF mRNA in astrocytes and neurons has also been confirmed with in situ hybridization [34]. An analysis of rat brain by Bacher and colleagues revealed MIF expression in neurons of the cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum, and pons [35]. Conboy et al. used immunohistochemistry to establish MIF expression in astrocytes and the subgranular zone of the hippocampus [36]. Interestingly, several of these areas contain proliferating or maturing cell populations, which is an important consideration for neurogenesis. There is significant regional association with glucocorticoid activation.

MIF has also been isolated in human brain tissue, with high levels of MIF mRNA expression in all regions [37]. Human neural MIF maintains high expression levels throughout life (compared to other tissues, whose levels decline with age), which has led some to propose a maintenance role for MIF in isomerization of reactive catecholamine metabolites to neuromelanin precursors [38]. Neuromelanin has been shown to be neuroprotective in the pathobiology of Parkinson’s disease due to its role as a scavenger and sink for toxic metabolites [39]. MIF has putative roles in several CNS inflammatory conditions, including multiple sclerosis [40] and cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [41], as well as being implicated in tumor growth in the CNS [19].

Extensive research has been done in identifying brain areas significant in depression. Schmidt and colleagues identified corticostriatal projection neurons as being essential for antidepressant response [42]. A 2008 review of neuroimaging, lesioning, and postmortem analyses posits a visceromotor network underlying the physiology of emotion and mood, with dysfunction in this circuit leading to the symptoms of depression [43]. This network involves interplay between the medial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and various limbic structures. It is noteworthy that this circuit includes the hippocampus, one of the areas previously identified as showing high MIF expression. This model has been applied to deep brain stimulation, an emerging approach to treatment-resistant depression [44].

MIF and glucocorticoids

As mentioned above, MIF opposes the activity of glucocorticoids on the immune system. This activity of glucocorticoids is well understood, and oral corticosteroids are in use by 0.5% of the general population. Glucocorticoids are produced endogenously as cortisol and released by the adrenal glands upon stimulation by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), secreted by corticotropic cells of the anterior pituitary; those cells release ACTH in response to stimulation by hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). This process is called the HPA axis. Corticosteroids bind cytosolic receptors that dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, downregulating transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreasing production of prostaglandins [21]. These effects are mediated by interactions with NFkB [45], an important transcriptional regulator. Specifically, glucocorticoids upregulate expression of annexin 1 [46] and MAPK phosphatase 1 (MPK1) [47], which both cause downregulation of PLA2. In addition to being involved with the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes from arachidonic acid, PLA2 also stimulates release of cytokines via Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) [48].

As discussed above, MIF causes upregulation of PLA2, likely downstream of ERK1/2 signaling pathways [28]. It may also affect NFkB via its interaction with Jab1, which can lead to suppression of the inhibitory binding factor of NFkB (IkB) [22]. MIF is expressed in cells at every level of the HPA axis [49]. Its plasma levels follow a circadian rhythm that is comparable to that observed for plasma cortisol [21], and it is released from pituitary cells by CRH in a dose-dependent fashion [50]. Cortisol has also been shown to induce secretion of MIF with a bell-shaped dose response curve [51], in which high levels suppress MIF production. This seems to indicate a homeostatic balance between MIF and glucocorticoids, with the dominant species determining whether to promote immune responses (in infection) or dampen them (to protect from the harmful effects of inflammation).

It is well established that patients with MDD experience dysregulation of the HPA axis, manifesting as alterations in cortisol secretion and loss of suppression by dexamethasone [52, 53]. These abnormalities manifest in 40 to 60% of patients with MDD [54]. This HPA dysregulation is similar to the hormonal changes observed in Cushing’s disease, albeit to a lesser degree [55]; interestingly, Cushing’s patients experience a greater incidence of mood disorders, which resolve upon normalization of cortisol levels [56]. Although patients with MDD do not experience Cushingoid symptoms per se, strong associations have been found between the hypercortisolism of depression and physical changes associated with Cushing’s disease, including hippocampal atrophy, cognitive impairment, and abdominal obesity [55]. These hormonal changes seem to be related to adrenal hyperresponsiveness to ACTH [54] as well as altered responses to glucocorticoids, especially at the level of negative feedback in the pituitary [17].

The relationship between altered glucocorticoid signaling and depression has been reiterated in mouse models, although there is still insufficient evidence to substantiate a true ‘glucocorticoid receptor theory of depression’ [57], especially since roughly half of MDD patients do not manifest HPA abnormalities. However, HPA dysregulation may represent one pathway among many that converge to produce the symptoms of depression. Significantly, stress and corticosteroids have also been shown to inhibit hippocampal neurogenesis; this effect is reversed by antidepressants [58]. MIF’s role in this scheme has been investigated: Edwards et al. found that MIF levels were 40% higher in healthy volunteers who showed depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and elevated MIF was associated with decreased cortisol response to acute stress and lower morning cortisol values [59].

MIF and antidepressant treatments

Antidepressant response is a commonly used paradigm in depression research. Since the pathobiology and genetics of depression remain unknown, and many of its symptoms are impossible to replicate in an animal model, it has become necessary to design experimental models based on reproducible responses to established antidepressant treatments [60, 61]. These models utilize both classical treatments, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), as well as new treatments like increased physical activity and deep brain stimulation [62].

MIF has been tested against traditional antidepressant treatments. An assay of motivated behavior has shown an association between the ERK1/2 pathway and responses to tricyclic antidepressants [63]. Conboy and colleagues determined that fluoxetine, a commonly administered SSRI [13], causes an increase in neurons immunoreactive for MIF. They also found that MIF knockout (KO) mice and mice given the MIF inhibitor [64] ISO-1 showed decreased neurogenesis after administration of fluoxetine. In addition, deletion of MIF resulted in increased depressive symptoms in the Porsolt forced swim test for behavioral despair (FST) and impairments in hippocampal spatial learning and memory in the Morris water maze. They concluded from these results that MIF is significant in the neurogenic effects of antidepressants [36].

Physical activity (PA) is emerging as an exciting new avenue of therapy for depression. PA has relatively few adverse effects, and can positively influence other physiological and psychological disorders. PA has been shown to be immunomodulatory, promoting expression of certain cytokines and immune cells and reducing others, as reviewed elsewhere [65]. PA also induces production of erythropoietin (EPO), a glycoprotein hormone involved in red blood cell hematopoiesis [66]. EPO and its receptor have recently been elaborated in the CNS [67], and they have been shown to have neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects [68].

Moon et al. found that the antidepressant effects of exercise were partially mediated by MIF, which they concluded functions as an antidepressant [69]. Using data from mRNA microarrays, they determined that both voluntary exercise and ECT induce MIF. Similar to the results from Conboy et al. [36], MIF−/− mice showed increased depressive behavior and decreased antidepressant effects from exercise on the FST. Intracerebroventricular (icv) MIF administration had a direct antidepressant effect on the FST. They also analyzed gene expression patterns for brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), an important species in neurogenesis [70], and tryptophan hydroxylase-2 (Tph2), a rate-limiting enzyme in brain production of serotonin [71]. Both were upregulated in exercise and icv administration of MIF. Induction of Tph2 by MIF was matched with increased expression of serotonin in a recombinant cell line. It was further determined that these effects are all dependent on CD74 and ERK1/2, both established factors in MIF signal transduction [20, 64].

MIF and neurogenesis

MIF is known to have a role in embryonic development and cellular proliferation. As mentioned above, it promotes cell growth and inhibits apoptosis via inhibition of p53, a tumor suppressor protein. Swant et al. established in fibroblasts that RhoA GTPase is an important link between MIF and cyclin D1, which promotes cell cycle progression by phosphorylation of Rb, another tumor suppressor protein [72]. Inactivation of Rb leads to disinhibition of E2F, which promotes synthesis of S phase proteins and subsequent cellular proliferation [73]. MIF directly stimulates activation of RhoA.

Ito and colleagues determined that MIF is an important factor in embryonic development of zebrafish, a commonly used model for embryogenesis. Using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) they detected widespread MIF expression in embryonic structures, including eyes, tectum, branchial arches, and gut structures. Using antisense Morpholino-mediated knockdown (MO), they determined that MIF MO fish displayed a reproducible phenotype of abnormal development in eyes and cartilage structures, and, significantly, in brain structures such as the tectum and fourth ventricle [74]. Similar expression patterns have been observed in avian, murine, and other mammalian models [75–77]. MIF has also been shown to promote proliferation and survival of neural stem progenitor cells in vitro[78].

It is notable that MIF expression in the brain is localized in regions of cellular proliferation. As discussed above, MIF expression has been found in proliferating cells of the subgranular zone of the hippocampus, and is modulated by treatments affecting neurogenesis (chronic stress, corticosteroids, and antidepressants). MIF deletion by genetics or inhibitors also attenuates both basal and induced neurogenesis [36]. Similarly, Moon et al. found that MIF induces the production of BDNF [69], whose role in neurogenesis is well-established [70]. A summary of results from significant animal studies of MIF and depression can be found in Table 1.

MIF as a biomarker

With inflammation implicated in pathophysiology of depression, several groups have examined cytokines as depression biomarkers [79]. Rodent studies have indicated that serum MIF increases in response to acute stress [49, 80]. Several groups have examined MIF levels in human serum in the context of depressive symptoms. A study of male undergraduate students presented with a public speaking task determined that subjects with mild to moderate depression on the BDI demonstrated higher baseline serum levels of MIF as well as increased lymphocytes [59, 81]. Similar results have been reported in pregnant women, where an association was determined between depressive symptoms and increased MIF. Increased serum MIF was also observed after an immune challenge in pregnant patients with depressive symptoms as measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [82]. Interestingly, studies of healthy patients with negative mood symptoms as measured by the Zung self-rating depression scale (SDS) showed no significant association between serum MIF and SDS mood scores [83]; associations were found with IL-1β, a species known to be elevated in depression [84].

MIF has also been examined as a biomarker in the context of clinical depression. In a drug trial examining celecoxib add-on therapy to reboxetine (a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor), MDD patients had an increased serum MIF at baseline with no change during treatment [85]. Similar results were found in an analysis of leukocyte mRNA expression in serum from participants in the Genome-based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression (GENDEP) project. In addition to observing increased MIF in MDD patients compared to healthy controls, the group also found that treatment responders had significantly higher levels of serum MIF than patients who resisted treatment. MIF levels were shown to reduce over time in this study, but this was not associated with treatment response [86]. Results of human studies with MIF and depression are summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

Despite significant evidence for MIF involvement in the pathobiology of depression, some uncertainty remains about its exact role. MIF is an established species in the brain with suggested protective roles against neurodegenerative disease [38]. Multiple groups have identified a role for MIF in mediating antidepressant activities, and have shown that loss of MIF results in an antidepressant phenotype; there is even evidence that MIF has direct antidepressant effects. These studies have linked MIF to monoamine production and neurogenesis, both implicated in the pathobiology of depression [36, 69]. Conversely, increased serum MIF has been identified in both patients with major depression and healthy subjects with depressive symptoms [81, 82, 85, 86], although these studies have shown mixed results [83]. At least one study has associated these changes with the HPA axis, which has also been implicated in depression [59]. See Figure 1 for a summary of putative roles for MIF in depression.

It seems counterintuitive to assert that MIF is both an antidepressant and a biomarker of depression. However, it is important to realize that the Conboy and Moon studies were working with MIF native to the brain, while the biomarker studies were analyzing MIF levels in peripheral blood. MIF does not cross the blood brain barrier [87, 88], and differential expression in the two areas may explain the differing observations. MIF levels in plasma may be incidental to the mechanisms of depression or may arise as a consequence of a different but related process. It is also possible that the two results are not mutually exclusive, and increased MIF in depressed individuals is a physiological adaptation to the pathobiological changes of depression. It is notable in this regard that increased MIF in depressed patients has been found to correlate with treatment response [86].

MIF underlies the pathophysiology of several disease conditions, and MIF inhibition is well characterized and widely used in research [64]. Anti-MIF antibodies are currently being investigated in Phase I clinical trials [89]. It seems inevitable that some form of MIF inhibitors will soon become available at the clinical level. When this occurs, MIF’s role in depression - whatever it may be - will be highly relevant. If MIF is found to promote depression, then MIF inhibitors could be investigated as antidepressants; ISO-1, the most tested MIF inhibitor, has already been shown to cross the blood brain barrier [36]. If MIF acts as an antidepressant, then anti-MIF therapeutics can be engineered not to cross the blood brain barrier, bypassing depression as a possible off-target effect.

Conclusion

There are clear gaps in the research concerning MIF and depression. Future studies should work to elucidate the relationship between central and peripheral MIF in depression, if any exists. Further work should also be done to clarify MIF’s role as a pro- or antidepressant and its place in the pathobiology of depression. It may be useful to further analyze relationships with factors in and out of the monoamine and neurogenic pathways that have been shown to impact depression. Imaging studies have emerged as an important modality in neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression [90, 91]; it may prove interesting to test how alterations in MIF expression affect the presentation of the disease on imaging studies. One advantage in these projects will be the fact that MIF is a well-studied molecule, with both established inhibitors and KO strains in rodent models.

Although there is much to be done, it seems beyond doubt that MIF has great potential in studies of the mechanisms of major depression. In addition to interacting with known elements involved in the physiological changes of depression, it is also active in the brain and can be shown to have independent effects on the depression phenotype. In addition to expanding our knowledge about this still-enigmatic disease, such studies can also inform current drug development efforts with anti-MIF therapy, as well as possibly provide the stagnant field of antidepressant treatment with a valuable new target in modifying the course of this disease.

Abbreviations

- ACTH:

-

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AP1:

-

activator protein 1

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- BDNF:

-

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CES-D:

-

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- CRH:

-

corticotrophin releasing hormone

- ECT:

-

electroconvulsive therapy

- EPO:

-

erythropoietin

- ERK:

-

extracellular signal-related kinase

- FST:

-

Porsolt forced swim test

- GENDEP:

-

Genome-based Therapeutic Drugs for Depression project

- HPA:

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- HRSD:

-

Hamilton Depression Scale 17-item version

- icv:

-

intracerebroventricular

- IkB:

-

inhibitory binding factor of NFkB

- IFN:

-

interferon

- IL:

-

interleukin

- Jab1:

-

JUN-activation domain binding protein 1

- JNK:

-

JUN N-terminal kinase

- KO:

-

knockout

- MADRS:

-

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDD:

-

major depressive disorder

- MIF:

-

macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- MO:

-

Morpholino-mediated knockdown

- NF:

-

nuclear factor

- PA:

-

physical activity

- PGE2:

-

prostaglandin E2

- PLA2:

-

phospholipase A2

- SDS:

-

Zung self-rating depression scale

- SSRI:

-

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- Tph2:

-

tryptophan hydroxylase-2

- UCLA-R:

-

Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale

- WISH:

-

whole-mount in situ hybridization.

References

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). 2013, Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 5

Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Stein DJ, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade L, Benjet C, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Haro JM, Hu CY, Karam A, Lee S, Lepine J-P, Matchsinger H, Mihaescu-Pintia C, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Ustün TB: Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011, 68: 90-100. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180.

Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, Bijl RV, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, Dragomirecka E, Kohn R, Keller M, Kessler RC, Kawakami N, Kiliç C, Offord D, Ustün TB, Wittchen H-U: The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003, 12: 3-21. 10.1002/mpr.138.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005, 62: 617-627. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.

Cowen PJ: Classification of depressive disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2013, 14: 3-13.

Kravitz RL, Ford DE: Introduction: chronic medical conditions and depression - the view from primary care. Am J Med. 2008, 121: S1-S7.

Katon W, Fan M-Y, Unützer J, Taylor J, Pincus H, Schoenbaum M: Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med. 2008, 23: 1571-1575. 10.1007/s11606-008-0731-9.

Biringer E, Mykletun A, Sundet K, Kroken R, Stordal KI, Lund A: A longitudinal analysis of neurocognitive function in unipolar depression. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007, 29: 879-891. 10.1080/13803390601147686.

Martínez-Arán A, Vieta E, Colom F, Torrent C, Sánchez-Moreno J, Reinares M, Benabarre A, Goikolea JM, Brugué E, Daban C, Salamero M: Cognitive impairment in euthymic bipolar patients: implications for clinical and functional outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2004, 6: 224-232. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00111.x.

Behnken A, Schöning S, Gerss J, Konrad C, de Jong-Meyer R, Zwanzger P, Arolt V: Persistent non-verbal memory impairment in remitted major depression - caused by encoding deficits?. J Affect Disord. 2010, 122: 144-148. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.010.

Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Warden D, Ritz L, Norquist G, Howland RH, Lebowitz B, McGrath PJ, Shores-Wilson K, Biggs MM, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, STAR*D Study Team: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006, 163: 28-40. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28.

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ: The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008, 455: 894-902. 10.1038/nature07455.

Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, Davis JM, Mann JJ: Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of six-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012, 69: 572-579.

Anisman H, Hayley S: Inflammatory factors contribute to depression and its comorbid conditions. Sci Signal. 2012, 5: pe45-pe45.

Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW: From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008, 9: 46-56. 10.1038/nrn2297.

Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL: Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009, 65: 732-741. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029.

Raison CL, Miller AH: When not enough is too much: the role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2003, 160: 1554-1565. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1554.

Dobos N, de Vries EFJ, Kema IP, Patas K, Prins M, Nijholt IM, Dierckx RA, Korf J, den JA B, Luiten PGM, Eisel ULM: The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in a mouse model of neuroinflammation-induced depression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 28: 905-915.

Savaskan NE, Fingerle-Rowson G, Buchfelder M, Eyüpoglu IY: Brain miffed by macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Int J Cell Biol. 2012, 2012: 1-11.

Calandra T, Roger T: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003, 3: 791-800. 10.1038/nri1200.

Flaster H, Bernhagen J, Calandra T, Bucala R: The macrophage migration inhibitory factor-glucocorticoid dyad: regulation of inflammation and immunity. Mol Endocrinol. 2007, 21: 1267-1280. 10.1210/me.2007-0065.

Kleemann R, Hausser A, Geiger G, Mischke R, Burger-Kentischer A, Flieger O, Johannes FJ, Roger T, Calandra T, Kapurniotu A, Grell M, Finkelmeier D, Brunner H, Bernhagen J: Intracellular action of the cytokine MIF to modulate AP-1 activity and the cell cycle through Jab1. Nature. 2000, 408: 211-216. 10.1038/35041591.

Calandra T, Echtenacher B, Roy DL, Pugin J, Metz CN, Hültner L, Heumann D, Männel D, Bucala R, Glauser MP: Protection from septic shock by neutralization of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Nat Med. 2000, 6: 164-170. 10.1038/72262.

Lue H, Kleemann R, Calandra T, Roger T, Bernhagen J: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): mechanisms of action and role in disease. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4: 449-460. 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01560-5.

Das R, Koo MS, Kim BH, Jacob ST: Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF) is a critical mediator of the innate immune response to mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013, 110 (32): E2997-E3006. 10.1073/pnas.1301128110.

Toso C, Emamaullee JA, Merani S, Shapiro AMJ: The role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor on glucose metabolism and diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008, 51: 1937-1946. 10.1007/s00125-008-1063-3.

Leng L, Bucala R: Insight into the biology of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) revealed by the cloning of its cell surface receptor. Cell Res. 2006, 16: 162-168. 10.1038/sj.cr.7310022.

Mitchell RA, Metz CN, Peng T, Bucala R: Sustained mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activation by macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). Regulatory role in cell proliferation and glucocorticoid action. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 18100-18106. 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18100.

Roger T, David J, Glauser MP, Calandra T: MIF regulates innate immune responses through modulation of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2001, 414: 920-924. 10.1038/414920a.

Hudson JD, Shoaibi MA, Maestro R, Carnero A, Hannon GJ, Beach DH: A proinflammatory cytokine inhibits p53 tumor suppressor activity. J Exp Med. 1999, 190: 1375-1382. 10.1084/jem.190.10.1375.

Rosengren E, Bucala R, Aman P, Jacobsson L, Odh G, Metz CN, Rorsman H: The immunoregulatory mediator macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) catalyzes a tautomerization reaction. Mol Med. 1996, 2: 143-149.

Kleemann R, Kapurniotu A, Frank RW, Gessner A, Mischke R, Flieger O, Jüttner S, Brunner H, Bernhagen J: Disulfide analysis reveals a role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) as thiol-protein oxidoreductase. J Mol Biol. 1998, 280: 85-102. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1864.

Nishibori M, Nakaya N, Tahara A, Kawabata M, Mori S, Saeki K: Presence of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in ependyma, astrocytes and neurons in the bovine brain. Neurosci Lett. 1996, 213: 193-196.

Ogata A, Nishihira J, Suzuki T, Nagashima K, Tashiro K: Identification of macrophage migration inhibitory factor mRNA expression in neural cells of the rat brain by in situ hybridization. Neurosci Lett. 1998, 246: 173-177. 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00203-1.

Bacher M, Meinhardt A, Lan HY, Dhabhar FS, Mu W, Metz CN, Chesney JA, Gemsa D, Donnelly T, Atkins RC, Bucala R: MIF expression in the rat brain: implications for neuronal function. Mol Med. 1998, 4: 217-230.

Conboy L, Varea E, Castro JE, Sakouhi-Ouertatani H, Calandra T, Lashuel HA, Sandi C: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is critically involved in basal and fluoxetine-stimulated adult hippocampal cell proliferation and in anxiety, depression, and memory-related behaviors. Mol Psychiatry. 2010, 16: 533-547.

Matsunaga J: Enzyme activity of macrophage migration inhibitory factor toward oxidized catecholamines. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 3268-3271. 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3268.

Solano F, Hearing VJ, García-Borrón JC: Neurotoxicity due to o-quinones: neuromelanin formation and possible mechanisms for o-quinone detoxification. Neurotox Res. 2000, 1: 153-169.

Rao K, Hegde M, Anitha S, Musicco M, Zucca F, Turro N, Zecca L: Amyloid β and neuromelanin - toxic or protective molecules? The cellular context makes the difference. Prog Neurobiol. 2006, 78: 364-373. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.03.004.

Kithcart AP, Cox GM, Sielecki T, Short A, Pruitt J, Papenfuss T, Shawler T, Gienapp I, Satoskar AR, Whitacre CC: A small-molecule inhibitor of macrophage migration inhibitory factor for the treatment of inflammatory disease. FASEB J. 2010, 24: 4459-4466. 10.1096/fj.10-162347.

Chen Y, Wu X, Yu S, Lin X, Wu J, Li L, Zhao J, Zhao Y: Neuroprotection of tanshinone IIA against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in rats. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7: e40165-10.1371/journal.pone.0040165.

Schmidt EF, Warner-Schmidt JL, Otopalik BG, Pickett SB, Greengard P, Heintz N: Identification of the cortical neurons that mediate antidepressant responses. Cell. 2012, 149: 1152-1163. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.038.

Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML: Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008, 213: 93-118. 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x.

Mayberg HS: Targeted electrode-based modulation of neural circuits for depression. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119: 717-725. 10.1172/JCI38454.

Ling J, Kumar R: Crosstalk between NFkB and glucocorticoid signaling: a potential target of breast cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2012, 322: 119-126. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.02.033.

Roviezzo F, Getting SJ, Paul-Clark MJ, Yona S, Gavins FNE, Perretti M, Hannon R, Croxtall JD, Buckingham JC, Flower RJ: The annexin-1 knockout mouse: what it tells us about the inflammatory response. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002, 53: 541-553.

Lasa M, Abraham SM, Boucheron C, Saklatvala J, Clark AR: Dexamethasone causes sustained expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 and phosphatase-mediated inhibition of MAPK p38. Mol Cell Biol. 2002, 22: 7802-7811. 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7802-7811.2002.

Swantek JL, Cobb MH, Geppert TD: Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) is required for lipopolysaccharide stimulation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) translation: glucocorticoids inhibit TNF-alpha translation by blocking JNK/SAPK. Mol Cell Biol. 1997, 17: 6274-6282.

Baugh JA, Donnelly SC: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a neuroendocrine modulator of chronic inflammation. J Endocrinol. 2003, 179: 15-23. 10.1677/joe.0.1790015.

Bucala R: MIF rediscovered: cytokine, pituitary hormone, and glucocorticoid-induced regulator of the immune response. FASEB J. 1996, 10: 1607-1613.

Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Metz CN, Spiegel LA, Bacher M, Donnelly T, Cerami A, Bucala R: MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature. 1995, 377: 68-71. 10.1038/377068a0.

Kathol RG, Jaeckle RS, Lopez JF, Meller WH: Pathophysiology of HPA axis abnormalities in patients with major depression: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 1989, 146: 311-317.

Pariante CM, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH: Glucocorticoid receptors in depression. Isr J Med Sci. 1995, 31: 705-712.

Parker KJ, Schatzberg AF, Lyons DM: Neuroendocrine aspects of hypercortisolism in major depression. Horm Behav. 2003, 43: 60-66. 10.1016/S0018-506X(02)00016-8.

Brown ES, Varghese FP, McEwen BS: Association of depression with medical illness: does cortisol play a role?. Biol Psychiatry. 2004, 55: 1-9.

Plotsky PM, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB: Psychoneuroendocrinology of depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998, 21: 293-307. 10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70006-X.

Neigh GN, Nemeroff CB: Reduced glucocorticoid receptors: consequence or cause of depression?. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006, 17: 124-125. 10.1016/j.tem.2006.03.002.

Joëls M, Karst H, Krugers HJ, Lucassen PJ: Chronic stress: implications for neuronal morphology, function and neurogenesis. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2007, 28: 72-96. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.04.001.

Edwards KM, Bosch JA, Engeland CG, Cacioppo JT, Marucha PT: Elevated macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is associated with depressive symptoms, blunted cortisol reactivity to acute stress, and lowered morning cortisol. Brain Behav Immun. 2010, 24: 1202-1208. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.011.

Cryan JF, Markou A, Lucki I: Assessing antidepressant activity in rodents: recent developments and future needs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002, 23: 238-245. 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)02017-5.

Berton O, Hahn CG, Thase ME: Are we getting closer to valid translational models for major depression?. Science. 2012, 338: 75-79. 10.1126/science.1222940.

Perez-Caballero L, Rez-Egea RPE, Romero-Grimaldi C, Puigdemont D, Molet J, Caso J-R, Mico J-A, Rez VPE, Leza J-C, Berrocoso E: Early responses to deep brain stimulation in depression are modulated by anti-inflammatory drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2013, 1-8. doi:10.1038/mp.2013.63

Gourley SL, Wu FJ, Kiraly DD, Ploski JE, Kedves AT, Duman RS, Taylor JR: Regionally specific regulation of ERK MAP kinase in a model of antidepressant-sensitive chronic depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 63: 353-359. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.016.

Al-Abed Y, VanPatten S: MIF as a disease target: ISO-1 as a proof-of-concept therapeutic. Future Med Chem. 2011, 3: 45-63. 10.4155/fmc.10.281.

Baune BT: Treating depression and depression-like behavior with physical activity: an immune perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2013, 1-27. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00003

Miskowiak KW, Vinberg M, Harmer CJ, Ehrenreich H, Kessing LV: Erythropoietin: a candidate treatment for mood symptoms and memory dysfunction in depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011, 219: 687-698.

Marti HH, Wenger RH, Rivas LA, Straumann U, Digicaylioglu M, Henn V, Yonekawa Y, Bauer C, Gassmann M: Erythropoietin gene expression in human, monkey and murine brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1996, 8: 666-676. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01252.x.

Brines M, Cerami A: Emerging biological roles for erythropoietin in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005, 6: 484-494. 10.1038/nrn1687.

Moon HY, Kim SH, Yang YR, Song P, Yu HS, Park HG, Hwang O, Lee-Kwon W, Seo JK, Hwang D, Choi JH, Bucala R, Ryu SH, Kim YS, Suh P-G: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor mediates the antidepressant actions of voluntary exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012, 109: 13094-13099. 10.1073/pnas.1205535109.

Shirayama Y, Chen AC-H, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression. J Neurosci. 2002, 22: 3251-3261.

Gutknecht L, Waider J, Kraft S, Kriegebaum C, Holtmann B, Reif A, Schmitt A, Lesch K-P: Deficiency of brain 5-HT synthesis but serotonergic neuron formation in Tph2 knockout mice. J Neural Transm. 2008, 115: 1127-1132. 10.1007/s00702-008-0096-6.

Swant JD: Rho GTPase-dependent signaling is required for macrophage migration inhibitory factor-mediated expression of cyclin D1. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280: 23066-23072. 10.1074/jbc.M500636200.

Weinberg RA: The retinoblastoma protein and cell cycle control. Cell. 1995, 81: 323-330. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90385-2.

Ito K, Yoshiura Y, Ototake M, Nakanishi T: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is essential for development of zebrafish, Danio rerio. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008, 32: 664-672. 10.1016/j.dci.2007.10.007.

Wistow GJ, Shaughnessy MP, Lee DC, Hodin J, Zelenka PS: A macrophage migration inhibitory factor is expressed in the differentiating cells of the eye lens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 1272-1275. 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1272.

Kobayashi S, Satomura K, Levsky JM, Sreenath T, Wistow GJ, Semba I, Shum L, Slavkin HC, Kulkarni AB: Expression pattern of macrophage migration inhibitory factor during embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 1999, 84: 153-156. 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00057-X.

Suzuki T, Ogata A, Tashiro K, Nagashima K, Tamura M, Nishihira J: Augmented expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in the telencephalon of the developing rat brain. Brain Res. 1999, 816: 457-462. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01179-2.

Ohta S, Misawa A, Fukaya R, Inoue S, Kanemura Y, Okano H, Kawakami Y, Toda M: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) promotes cell survival and proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. J Cell Sci. 2012, 125: 3210-3220. 10.1242/jcs.102210.

Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctôt KL: A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 67: 446-457. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033.

Lu XT, Liu YF, Zhao L, Li WJ, Yang RX, Yan FF, Zhao YX, Jiang F: Chronic psychological stress induces vascular inflammation in rabbits. Stress. 2013, 16: 87-98. 10.3109/10253890.2012.676696.

Hawkley LC, Bosch AJ, Engeland GC, Marucha TP, Cacioppo TJ: Cytokines. 2006, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 33487-2742

Christian LM, Franco A, Iams JD, Sheridan J, Glaser R: Depressive symptoms predict exaggerated inflammatory responses to an in vivo immune challenge among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2010, 24: 49-53. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.055.

Katsuura S, Kamezaki Y, Yamagishi N, Kuwano Y, Nishida K, Masuda K, Tanahashi T, Kawai T, Arisawa K, Rokutan K: Circulating vascular endothelial growth factor is independently and negatively associated with trait anxiety and depressive mood in healthy Japanese university students. Int J Psychophysiol. 2011, 81: 38-43. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.04.004.

Zunszain PA, Hepgul N, Pariante CM: Inflammation and depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2013, 14: 135-151.

Musil R, Schwarz MJ, Riedel M, Dehning S, Cerovecki A, Spellmann I, Arolt V, Müller N: Elevated macrophage migration inhibitory factor and decreased transforming growth factor-beta levels in major depression - No influence of celecoxib treatment. J Affect Disord. 2011, 134: 217-225. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.047.

Cattaneo A, Gennarelli M, Uher R, Breen G, Farmer A, Aitchison KJ, Craig IW, Anacker C, Zunsztain PA, McGuffin P, Pariante CM: Candidate genes expression profile associated with antidepressants response in the GENDEP study: differentiating between baseline ‘Predictors’ and longitudinal ‘Targets’. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012, 38: 377-385.

Bacher M, Weihe E, Dietzschold B, Meinhardt A, Vedder H, Gemsa D, Bette M: Borna disease virus-induced accumulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in rat brain astrocytes is associated with inhibition of macrophage infiltration. Glia. 2002, 37: 291-306. 10.1002/glia.10013.

Arjona A, Foellmer HG, Town T, Leng L, McDonald C, Wang T, Wong SJ, Montgomery RR, Fikrig E, Bucala R: Abrogation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor decreases West Nile virus lethality by limiting viral neuroinvasion. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117: 3059-3066. 10.1172/JCI32218.

Kyhos B, Spak D: Baxter initiates phase I clinical trial with anti-MIF antibody in patients with solid tumors. 2012, 1-2. http://www.baxter.com/press_room/press_releases/2012/09_05_12_anti-mif.html.

Schneider B, Prvulovic D: Novel biomarkers in major depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013, 26: 47-53. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835a5947.

Pandya M, Altinay M, Malone DA, Anand A: Where in the brain is depression?. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14: 634-642. 10.1007/s11920-012-0322-7.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roman Sankowski, Sonya VanPatten, and Christine Metz for their critical reading and assistance with the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Joshua Bloom has received an MD/PhD candidate stipend from the Hofstra North Shore LIJ School of Medicine. Yousef Al Abed is the inventor or co-inventor of several small-molecule inhibitors of MIF. The authors declare no other conflicts of interests.

Authors’ contributions

JB designed and drafted the manuscript; YA conceived of the study, helped draft the manuscript, and gave final approval of the version to be published. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bloom, J., Al-Abed, Y. MIF: Mood Improving/Inhibiting Factor?. J Neuroinflammation 11, 11 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-11-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-11-11