Abstract

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products are prepared from purified plasma immunoglobulins from large numbers of healthy donors. Pilot studies with the IVIG preparations Octagam and Gammagard in individuals with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggested stabilization of cognitive functioning in these patients, and a phase II trial with Gammagard reported similar findings. However, subsequent reports from Octagam’s phase II trial and Gammagard’s phase III trial found no evidence for slowing of AD progression. Although these recent disappointing results have reduced enthusiasm for IVIG as a possible treatment for AD, it is premature to draw final conclusions; a phase III AD trial with the IVIG product Flebogamma is still in progress. IVIG was the first attempt to use multiple antibodies to treat AD. This approach should be preferable to administration of single monoclonal antibodies in view of the multiple processes that are thought to contribute to AD neuropathology. Development of “AD-specific” preparations with higher concentrations of selected human antibodies and perhaps modified in other ways (such as increasing their anti-inflammatory effects and/or ability to cross the blood–brain barrier) should be considered. Such preparations, if generated with recombinant technology, could overcome the problems of high cost and limited supplies, which have been major concerns relating to the possible widespread use of IVIG in AD patients. This review summarizes the recent AD IVIG trials and discusses the major issues relating to possible use of IVIG for treating AD, as well as the critical questions which remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The severity of the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) problem in the US is indicated by recent statistics from the Alzheimer’s Association [1]. Approximately 5.4 million Americans are currently diagnosed with AD, including one in eight individuals aged 65 and older. By 2025 the number of Americans aged 65 and older with AD is expected to reach 6.7 million. Payments for health care, long-term care, and hospice for AD patients, which are currently estimated at $200 billion, are expected to be $1.1 trillion (in 2012 dollars) by 2050.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) products are being investigated as potential agents for treatment or prevention of AD. IVIG is prepared from plasma immunoglobulins from large numbers (>10,000) of healthy donors. It is used to treat a range of autoimmune, infectious, and idiopathic disorders [2]. The IVIG product Octagam (Octapharma) was shown by Dodel et al. in 2002 to contain antibodies to Aβ, suggesting that IVIG might be useful for treatment of AD [3]. This provided the rationale for IVIG pilot studies in AD patients. The results of these studies were encouraging [4, 5], leading to phase II AD trials with these products. Positive results were reported for one of the two IVIG products [6, 7] but not the other one [8]. More recently, negative results were reported in a phase III IVIG study [9]. An additional phase III AD trial with another IVIG product is in progress.

As of this writing (May 2013) it is unclear whether any IVIG products will offer a breakthrough for treatment of AD. Because these preparations differ in their concentrations of antibodies to Aβ [10–12] and tau protein [13], there may be differences between them with regard to their efficacies in AD. This purpose of this review is to summarize the IVIG AD trials conducted to date, the issues raised by the potential use of IVIG for treatment of AD, and critical questions which remain.

Clinical trials with IVIG in AD patients

IVIG treatment of AD patients was first reported in a pilot study in 2004 [4]. Five patients with mild to moderate AD [Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) mean score 19.4] received Octagam (Octapharma; dose = 0.4 g/kg) on 3 successive days, every 4 weeks for 6 months. MMSE scores improved slightly in four of the AD patients and were unchanged in the fifth one, while their Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive sub-scale (ADAS-cog) scores decreased, suggesting increased cognitive functioning, in four patients and did not change in the fifth one. In 2009 results were published [5] from a pilot study in which eight AD patients (mean MMSE score 23.5) were administered Gammagard S/D (Baxter Healthcare). After 6 months of treatment the mean MMSE score increased to 26.0, reflecting increased scores for six patients and no change in scores for two patients. After a 3-month washout period, the mean MMSE score returned to baseline (23.9). Following an additional 9 months of treatment, MMSE scores were essentially unchanged (mean 24.0).

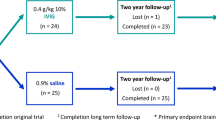

Before publishing these results, in 2006 Baxter began a double-blind Phase II AD trial with Gammagard. Improved outcomes were noted in the Gammagard-treated subjects compared to those initially treated with placebo at 3, 6, and 9 months [6]. The four patients who received Gammagard at 0.4 g/kg every 2 weeks for 36 months showed no evidence of further cognitive or memory decline [7].

The results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 24-week phase II AD trial with Octagam were published in January 2013 [8]. Octagam had no apparent effects on cognitive or functional scores in the AD patients. No increase was found for plasma Aβ1-40; this had been reported in the pilot studies and suggested that IVIG products might increase efflux of Aβ from the brain. The only positive finding reported in this study, less reduction in glucose metabolism in some brain regions in the Octagam-treated individuals, was of uncertain significance.

In May 2013, the results of a placebo-controlled phase III AD trial with Gammagard were announced [9]. Three hundred ninety patients had been treated every 2 weeks for 18 months with 200 mg/kg Gammagard, 400 mg/kg Gammagard, or placebo. No significant differences were found for the rate of cognitive decline between the Gammagard-treated group and placebo group.

Two AD-related IVIG trials are still in progress. Flebogamma (Grifols Biologicals) is being evaluated, together with albumin, in an AD phase III trial, and NewGam (Octapharma) is being investigated by Sutter Health in a phase II trial to determine its effects in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and its influence on the risk for these patients to develop AD. A possible reason for the failures in the most recent IVIG trials is that by the time AD’s clinical features become evident, its pathology, including extensive neuronal loss, is already wellestablished. The trial with MCI patients should provide an indication of whether earlier IVIG treatment may be beneficial. The findings of a retrospective study [14], that individuals 65 years of age and older who had received IVIG had a significantly reduced risk for developing AD and related disorders compared to subjects not receiving IVIG support this possibility.

Considerations relating to treatment of AD with IVIG products

Economic considerations

Approximately 22 million plasma donations were collected in the US in 2009. Processing of a plasma sample into IVIG requires about 9 months. The use of IVIG for treatment of AD could pose a threat to its supplies. Solutions that have been suggested to this problem include new manufacturing processes, use of recombinant technology to produce IVIG, or administration of specific antibodies in place of IVIG [15]. Because of problems with obtaining adequate amounts of IVIG, some hospitals require consideration of alternatives to IVIG for treatment of patients with neurological disorders [16].

IVIG treatment is expensive, although its actual cost varies with the dose, frequency of administration, and home vs. hospital infusion. The Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 fixed Medicare’s IVIG reimbursement rate to doctors and hospitals at the average sale price for IVIG plus 6%. Although the federal “340B drug discount” program mandates discounted IVIG prices for hospitals that provide high volumes of care to low-income patients [17], some hospitals have been unable to buy IVIG at these prices [18].

Potential side effects of IVIG

Thromboembolic events

IVIG can lead to thromboemboli because it increases serum viscosity, resulting in reduced blood flow [19]. Pre-existing vascular disease and immobility, additional factors that increase the risk for thromboembolic events [20], are often present in elderly individuals, including those with AD [21, 22]. In patients with neuropathies that received IVIG, immobility was found to be an independent predictor for the development of thromboemboli [23]. Vascular disease and immobility in AD patients could therefore increase the risk of these individuals for IVIG-induced thromboembolic events.

Renal problems

Renal dysfunction, acute renal failure, and osmotic nephrosis can result from IVIG treatment in patients with predisposing conditions such as renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, age > 65, volume depletion, sepsis, or receiving nephrotoxic drugs [24, 25]. This is particularly true for IVIG products that use sucrose as a stabilizing agent. The prevalence of chronic renal disease increases with age, peaking at nearly 24% at ages 70–74 [26], so elderly individuals are likely to have an increased risk for IVIG-induced kidney problems because of pre-existing renal disease. AD patients with impaired kidney function may therefore not be candidates for IVIG treatment.

Hematological deficits

Decreases in WBCs, RBCs, and platelets have been reported after IVIG treatment [27–30]. The mechanisms responsible for these alterations are unclear. IVIG can stimulate platelet aggregation [31], which could reduce platelet counts. Binding of high-molecular-weight IgG complexes in IVIG to RBCs could decrease hematocrit levels in IVIG-treated patients by increasing RBC sequestration [32]. Binding of neutrophils to the vascular wall and migration of these cells into a storage pool has been suggested as a mechanism for IVIG-induced neutropenia [33]. Similar to the situation with regard to renal problems, individuals with AD who have hematological abnormalities may not be able to receive IVIG.

Potential mechanisms of action of IVIG in AD

IVIG products are thought to contain the full range of antibodies present in the human repertoire, estimated at 109[15]. IVIG’s mechanisms of action in different disorders are generally poorly understood. It contains several antibodies that have the potential to reduce AD-type pathology, but whether these antibodies can actually do so is unclear.

Anti-Aβ effects

IVIG products contain antibodies to Aβ oligomers and fibrils [34] and perhaps also to monomeric Aβ [11, 35]. These drugs differ in their levels of anti-Aβ antibodies [10–12]. IVIG has been shown in vitro to disaggregate preformed Aβ fibrils, promote Aβ phagocytic removal [36], protect against Aβ neurotoxicity [35, 37], and prevent formation of Aβ soluble oligomers [11]. But studies in mouse models of AD have produced conflicting results as to whether IVIG products can reduce brain Aβ. Magga et al. [38] found that Gammagard promoted microglial-mediated clearance of Aβ in experiments with brain sections from APP/PS1 mice and reduced in vitro Aβ fibril formation, but the latter effect was not specific for its anti-Aβ antibodies. Dodel et al. [37] treated APP695 double mutant mice with purified anti-Aβ antibodies from Octagam for 4 weeks beginning at 3 or 12 months of age. Reduced plaque counts were found in the younger mice but not in the older mice. Puli et al. [39] treated TgApdE9 mice with Gammagard beginning at 4 months of age, for 3 or 8 months. In the 3-month-treated group, there were no effects on hippocampal plaque counts or brain Aβ. After 8 months, there were still no differences in plaque counts between treatment and control groups. Surprisingly, soluble Aβ levels in hippocampus were increased in treated mice.

IVIG’s antibodies recognize multiple sites on conformational Aβ epitopes, and its main binding to Aβ is reportedly to Aβ25-40 [12, 37]. This differs from the monoclonal anti-Aβ antibodies that have been used in clinical trials, Bapineuzumab and Solanezumab, which recognize only one epitope in linear Aβ and bind to Aβ1-5 and Aβ13-28, respectively [40]. A recent review [41] suggested that using the IVIG polyclonal antibody approach in an effort to deplete the spectrum of aggregated Aβ species might be more promising than using monoclonal antibodies targeting a single Aβ species.

Anti-inflammatory effects

IVIG can inhibit complement activation [42], neutralize inflammatory cytokines [43], and modulate chemokine expression [44] and regulatory T cell subsets [45]. However, its main anti-inflammatory effects are thought to be due to its IgG Fc fragments [46, 47]. IVIG may not have reduced brain inflammation in the AD clinical trials because high doses (1–2 g/kg) are required for it to exert these effects [48]. Ravetch and colleagues investigated the mechanism by which IVIG’s Fc fragment produces anti-inflammatory effects. The constant domain of IgG’s Fc contains a glycan (a core heptapolysaccharide containing N-acetylglucosamine and mannose at Asn297) [49]. In serum antibodies, this includes a terminal sialic acid, which is responsible for Fc’s anti-inflammatory effects [50]. This form of the carbohydrate is present in only 1-3% of IVIG’s IgG molecules, which may explain why high-dose IVIG is required to produce anti-inflammatory effects [51].

Possible anti-tau effects

Cognitive deficits in AD strongly correlate with neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) density and distribution [52, 53]. Aggregation and hyperphosphorylation of tau are required to produce NFTs. Studies in transgenic mouse models of tauopathy found that administration of antibodies to phosphorylated tau reduced tau pathology [54, 55], so if IVIG contains such antibodies, they might be beneficial for treatment of AD. We recently reported the presence of antibodies to recombinant human tau, which is unphosphorylated, in IVIG products [13]. The significance of these antibodies to “normal” tau (i.e., whether these antibodies can reduce tau oligomer formation or inhibit its neurotoxicity) and whether IVIG also contains antibodies to aggregated and hyperphosphorylated tau are unknown.

Alteration of Aβ passage in and out of the brain

Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) form when reducing sugars react with amino groups in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [56]. The receptor for AGEs (RAGE) is present on the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [57], where it transports Aβ into the brain [58]. Anti-RAGE antibodies have been reported in IVIG [59]. These antibodies could reduce Aβ influx into the brain.

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) is the main receptor for transporting Aβ out of the brain [60]. LRP-1 expression on the BBB is reduced in AD [61]. Soluble LRP (sLRP) has also been reported in IVIG [59]. sLRP binds 70–90% of plasma Aβ, preventing it from entering the brain [62], so increasing peripheral blood sLRP levels through IVIG treatment might help to lower brain Aβ levels.

Non-antibody-mediated effects

IVIG contains other non-antibody proteins in addition to sLRP, which could influence its actions in AD in ways that are not clear. Interferon-γ, an inflammatory cytokine that also has some anti-inflammatory actions [63], is present in IVIG [64]. Soluble human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I and II molecules are present in some IVIG products, as are their “physiological ligands,” CD4 and CD8 [65, 66]. Soluble CD4 in IVIG might interfere with HLA class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells, competing with HLA-class II-restricted T cells and possibly causing immunosuppression [66, 67]. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and TGF-β2 are also present in IVIG [68].

TGF-β1 is increased in AD brain, where it is associated with plaques [69], but it also may promote Aβ clearance [70], so its significance in AD is unclear.

Might IVIG products differ with respect to their effects in AD?

Differences have been reported between IVIG products for the concentrations of some of their antibodies and their biological activities [71–75]. These may be due to differences in manufacturing practices and/or the antigenic exposure of the plasma donors. With regard to AD, differences between IVIG preparations have been found for anti-Aβ [10–12] and anti-tau antibodies [13], as mentioned earlier. Determination of whether IVIG products differ in their ability to slow AD’s progression will require comparative studies, as have been done for Kawasaki disease [76] and primary immune deficiency [77].

How might the IVIG approach to AD treatment be improved?

Production of an “AD-specific” human immunoglobulin preparation would allow selected antibodies to be administered in higher concentrations than is possible with unfractionated IVIG. There are precedents for this. Polyclonal anti-D, a type of IVIG consisting of plasma from RhD-negative donors immunized to the D antigen [78], has been used to treat idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura [79, 80], and Shoenfeld and colleagues [81] have generated specific IVIG (sIVIG) preparations for a number of immune-mediated conditions including lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome. These antibodies could be produced with recombinant technology to avoid potential supply difficulties. A second possibility could be to administer multiple “humanized” mouse monoclonal antibodies with antigenic specificities similar to those of the antibodies in the AD-specific human IgG preparations. Single chain antibody fragments, which have been suggested as alternatives to monoclonal antibodies for AD treatment [82], should have better BBB penetration than intact IgG molecules. Still another alternative could be administration of recombinant sialylated Fc fragments, as suggested by Bayry et al. [15] for autoimmune diseases; as discussed above, this modification increases Fc’s anti-inflammatory properties [49, 50]. Sialic acid-enriched immunoglobulins have been obtained from IVIG by lectin fractionation [49, 83].

Critical questions remaining

The most important question relating to AD treatment with IVIG is clearly whether any IVIG products will consistently slow clinical progression of this disorder. Questions that, if addressed, could lead to improved efficacy for IVIG in the treatment of AD include the following:

-

1.

Regarding the antibodies in IVIG that have been identified against AD pathological proteins: what are their effects in mouse transgenic models of AD that develop both plaques and NFTs? (Although the complement membrane attack complex, C5b-9, is present on plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the AD brain [84, 85], the currently available mouse transgenic models of AD do not demonstrate this late-stage complement activation [86], so the effects of IVIG’s anti-complement antibodies on this process cannot presently be studied in animal models of AD.)

-

2.

What other AD-related antibodies are present in IVIG? (Does IVIG have antibodies against aggregated or hyperphosphorylated tau or antibodies that have antioxidant effects? Do its anti-Fas antibodies [72] have any relevance for AD treatment?)

-

3.

Do IVIG’s anti-idiotypic antibodies influence its effects in AD? These antibodies are thought to be responsible for IVIG’s benefits in autoimmune disorders [87], but their effects in AD are unknown.

-

4.

Are IVIG’s effects in AD similar between apoE4 carriers and non-carriers? (In the phase III Gammagard trial [9], it was suggested that the 400 mg/kg dose may have been of some benefit to apoE4+ AD patients).

-

5.

Does IVIG treatment of AD patients increase their risk for microhemorrhage? (In the phase II Octagam study, 14% of the Octagam-treated patients had microhemorrhages vs. none in the placebo group [8]).

Conclusions

The IVIG trials reported to date in AD patients have produced conflicting findings. Because the most recent trials produced negative results, enthusiasm for IVIG as a treatment for AD has been reduced, although hope remains that the phase III trial with Flebogamma will produce positive results. Multiple antibody therapy for AD, as typified by IVIG, should have advantages over administration of individual monoclonal antibodies. To identify which antibodies should be included in an AD-specific IVIG preparation, more must be known about the range of anti-AD antibodies in IVIG and their effects on AD pathology in animal models. Such an AD-specific IVIG preparation, modified to increase the concentration, anti-inflammatory activity, and perhaps the brain penetration of its antibodies, might be more beneficial to AD patients than treatment with unfractionated IVIG.

References

A's A: Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2012,2012(8):131–168.

Scheinfeld NS: Intravenous Immunoglobulin. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/210367-overview

Dodel R, Hampel H, Depboylu C, Lin S, Gao F, Schock S, Jäckel S, Wei X, Buerger K, Höft C, Hemmer B, Möller HJ, Farlow M, Oertel WH, Sommer N, Du Y: Human antibodies against amyloid beta peptide: a potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 2002, 52:253–256.

Dodel RC, Du Y, Depboylu C, Hampel H, Frölich L, Haag A, Hemmeter U, Paulsen S, Teipel SJ, Brettschneider S, Spottke A, Nölker C, Möller HJ, Wei X, Farlow M, Sommer N, Oertel WH: Intravenous immunoglobulins containing antibodies against beta-amyloid for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004, 75:1472–1474.

Relkin NR, Szabo P, Adamiak B, Burgut T, Monthe C, Lent RW, Younkin S, Younkin L, Schiff R, Weksler ME: 18-Month study of intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009, 30:1728–1736.

Science Daily: Results Of 9-Month Phase II Study Of Gammagard Intravenous Immunoglobulin. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/07/080730175522.htm

Medpage Today: IVIG Stops Alzheimer's in Its Tracks. http://www.medpagetoday.com/MeetingCoverage/AAIC/33780

Dodel R, Rominger A, Bartenstein P, Barkhof F, Blennow K, Förster S, Winter Y, Bach JP, Popp J, Alferink J, Wiltfang J, Buerger K, Otto M, Antuono P, Jacoby M, Richter R, Stevens J, Melamed I, Goldstein J, Haag S, Wietek S, Farlow M, Jessen F: Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12:233–243.

Medpage Today: Alzheimer’s Disease: IVIG Fails in Trial. http://www.medpagetoday.com/Neurology/AlzheimersDisease/38939

Safavi A, Langevin M, Vandeberg P, Novokhatny V, Scuderi P, Mohn G, Petteway S: Comparison of several human immunoglobulin products for anti-Aβ1–42 titer, 10th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. Madrid, Spain: International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; 2006.

Klaver AC, Finke JM, Digambaranath J, Balasubramaniam M, Loeffler DA: Antibody concentrations to Abeta1–42 monomer and soluble oligomers in untreated and antibody-antigen-dissociated intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Int Immunopharmacol 2010, 10:115–119.

Balakrishnan K, Andrei-Selmer LC, Selmer T, Bacher M, Dodel R: Comparison of intravenous immunoglobulins for naturally occurring autoantibodies against amyloid-beta. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 20:135–143.

Smith LM, Coffey MP, Klaver AC, Loeffler DA: Intravenous immunoglobulin products contain specific antibodies to recombinant human tau protein. Int Immunopharmacol 2013, 16:424–428. [Epub ahead of print]

Fillit H, Hess G, Hill J, Bonnet P, Toso C: IV immunoglobulin is associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Neurology 2009, 73:180–185.

Bayry J, Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV: Shortage of human intravenous immunoglobulin–reasons and possible solutions. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2007, 3:120–121.

Winters JL, Brown D, Hazard E, Chainani A, Andrzejewski C Jr: Cost-minimization analysis of the direct costs of TPE and IVIg in the treatment of Guillain-Barré syndrome. BMC Health Serv Res 2011, 11:101.

Public Hospital Pharmacy Coalition: An Overview of The Section 340B Drug Discount Program. http://www.cjaonline.net/events/SustSeries/Calls/Call20080918/OverviewSection340B2.pdf

Public Hospital Pharmacy Coalition: Hospitals Struggle to Access Key Blood Products at Affordable Prices. http://www.snhpa.org/public/documents/pdfs/IVIGPressReleaseandSummary.pdf

Dalakas MC: High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin and serum viscosity: risk of precipitating thromboembolic events. Neurology 1994, 44:223–226.

Brannagan TH 3rd: Intravenous gammaglobulin (IVIg) for treatment of CIDP and related immune-mediated neuropathies. Neurology 2002, 59:S33-S40.

Stefanova E, Pavlovic A, Jovanovic Z, Veselinovic N, Despotovic I, Stojkovic T, Sternic N, Kostic V: Vascular risk factors in Alzheimer's disease—Preliminary report. J Neurol Sci 2012, 322:166–169.

Kalaria RN, Akinyemi R, Ihara M: Does vascular pathology contribute to Alzheimer changes? J Neurol Sci 2012, 322:141–147.

Rajabally YA, Kearney DA: Thromboembolic complications of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients with neuropathy: a two-year study. J Neurol Sci 2011, 308:124–127.

Baxter Healthcare: GAMMAGARD LIQUID [Immune Globulin Infusion (Human)] 10%. http://www.baxter.com/products/biopharmaceuticals/downloads/gamliquid_PI.pdf

Haskin JA, Warner DJ, Blank DU: Acute renal failure after large doses of intravenous immune globulin. Ann Pharmacother 1999, 33:800–803.

Zhang QL, Koenig W, Raum E, Stegmaier C, Brenner H, Rothenbacher D: Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: results from a population of older adults in Germany. Prev Med 2009, 48:122–127.

Duhem C, Dicato MA, Ries F: Side-effects of intravenous immune globulins. Clin Exp Immunol 1994, 97:79–83.

Bajaj NP, Henderson N, Bahl R, Stott K, Clifford-Jones RE: Call for guidelines for monitoring renal function and haematological variables during intravenous infusion of immunoglobulin in neurological patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001, 71:562–563.

Brox AG, Cournoyer D, Sternbach M, Spurll G: Hemolytic anemia following intravenous gamma globulin administration. Am J Med 1987, 82:633–635.

Frame WD, Crawford RJ: Thrombotic events after intravenous immunoglobulin. Lancet 1986, 2:468.

Pollreisz A, Assinger A, Hacker S, Hoetzenecker K, Schmid W, Lang G, Wolfsberger M, Steinlechner B, Bielek E, Lalla E, Klepetko W, Volf I, Ankersmit HJ: Intravenous immunoglobulins induce CD32-mediated platelet aggregation in vitro. Br J Dermatol 2008, 159:578–584.

Kessary-Shoham H, Levy Y, Shoenfeld Y, Lorber M, Gershon H: In vivo administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) can lead to enhanced erythrocyte sequestration. J Autoimmun 1999, 13:129–135.

Matsuda M, Hosoda W, Sekijima Y, Hoshi K, Hashimoto T, Itoh S, Ikeda S: Neutropenia as a complication of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in adult patients with neuroimmunologic disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol 2003, 26:306–311.

O'Nuallain B, Acero L, Williams AD, Koeppen HP, Weber A, Schwarz HP, Wall JS, Weiss DT, Solomon A: Human plasma contains cross-reactive Abeta conformer-specific IgG antibodies. Bioch 2008, 47:12254–12256.

Szabo P, Relkin N, Weksler ME: Natural human antibodies to amyloid beta peptide. Autoimmun Rev 2008, 7:415–420.

Istrin G, Bosis E, Solomon B: Intravenous immunoglobulin enhances the clearance of fibrillar amyloid-beta peptide. J Neurosci Res 2006, 84:434–443.

Dodel R, Balakrishnan K, Keyvani K, Deuster O, Neff F, Andrei-Selmer LC, Röskam S, Stüer C, Al-Abed Y, Noelker C, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Oertel W, Du Y, Bacher M: Naturally occurring autoantibodies against beta-amyloid: investigating their role in transgenic animal and in vitro models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 2011, 31:5847–5854.

Magga J, Puli L, Pihlaja R, Kanninen K, Neulamaa S, Malm T, Härtig W, Grosche J, Goldsteins G, Tanila H, Koistinaho J, Koistinaho M: Human intravenous immunoglobulin provides protection against Aβ toxicity by multiple mechanisms in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2010, 7:90.

Puli L, Pomeshchik Y, Olas K, Malm T, Koistinaho J, Tanila H: Effects of human intravenous immunoglobulin on amyloid pathology and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2012, 9:105.

Panza F, Frisardi V, Solfrizzi V, Imbimbo BP, Logroscino G, Santamato A, Greco A, Seripa D, Pilotto A: Immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: from anti-β-amyloid to tau-based immunization strategies. Immunotherapy 2012, 4:213–238.

Moreth J, Mavoungou C, Schindowski K: Passive anti-amyloid immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease: What are the most promising targets? Immun Ageing 2013, 10:18. [Epub ahead of print]

Machimoto T, Guerra G, Burke G, Fricker FJ, Colona J, Ruiz P, Meier-Kriesche HU, Scornik J: Effect of IVIG administration on complement activation and HLA antibody levels. Transpl Int 2010, 23:1015–1022.

Abe Y, Horiuchi A, Miyake M, Kimura S: Anti-cytokine nature of natural human immunoglobulin: one possible mechanism of the clinical effect of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Immunol Rev 1994, 139:5–19.

Pigard N, Elovaara I, Kuusisto H, Paalavuo R, Dastidar P, Zimmermann K, Schwarz HP, Reipert B: Therapeutic activities of intravenous immunoglobulins in multiple sclerosis involve modulation of chemokine expression. J Neuroimmunol 2009, 209:114–120.

Kessel A, Ammuri H, Peri R, Pavlotzky ER, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y, Toubi EJ: Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy affects T regulatory cells by increasing their suppressive function. J Immunol 2007, 179:5571–5575.

Samuelsson A, Towers TL, Ravetch JV: Anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory Fc receptor. Science 2001, 291:484–486.

Debré M, Bonnet MC, Fridman WH, Carosella E, Philippe N, Reinert P, Vilmer E, Kaplan C, Teillaud JL, Griscelli C: Infusion of Fc gamma fragments for treatment of children with acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet 1993, 342:945–949.

Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV: Anti-inflammatory actions of intravenous immunoglobulin. Annu Rev Immunol 2008, 26:513–533.

Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV: Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science 2006, 313:670–673.

Anthony RM, Nimmerjahn F, Ashline DJ, Reinhold VN, Paulson JC, Ravetch JV: Recapitulation of IVIG anti-inflammatory activity with a recombinant IgG Fc. Science 2008, 320:373–376.

Anthony RM, Wermeling F, Karlsson MC, Ravetch JV: Identification of a receptor required for the anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105:19571–19578.

Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT: Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1992, 42:631–639.

Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bussière T, Bouras C, Kövari E, Perl DP, Morrison JH, Gold G, Hof PR: Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol 2003, 60:1495–1500.

Chai X, Wu S, Murray TK, Kinley R, Cella CV, Sims H, Buckner N, Hanmer J, Davies P, O'Neill MJ, Hutton ML, Citron M: Passive immunization with anti-tau antibodies in two transgenic models: reduction of tau pathology and delay of disease progression. J Biol Chem 2011, 286:34457–34467.

Boutajangout A, Ingadottir J, Davies P, Sigurdsson EM: Passive immunization targeting pathological phospho-tau protein in a mouse model reduces functional decline and clears tau aggregates from the brain. J Neurochem 2011, 118:658–667.

Singh R, Barden A, Mori T, Beilin L: Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia 2001, 44:129–146.

Schmidt AM, Sahagan B, Nelson RB, Selmer J, Rothlein R, Bell JM: The role of RAGE in amyloid-beta peptide-mediated pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2009, 10:672–680.

Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B: RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood–brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med 2003, 9:907–913.

Weber A, Engelmaier A, Teschner W, Ehrlich HJ, Schwarz HP: Intravenous immunoglobulin (Vig) Gammagard liquid contains anti-RAGE IgG and sLRP. Alzheimer’s Association 2009 International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; 3–248.

Shibata M, Yamada S, Kumar SR, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, Holtzman DM, Miller CA, Strickland DK, Ghiso J, Zlokovic BV: Clearance of Alzheimer's amyloid-ss(1–40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood–brain barrier. J Clin Invest 2000, 106:1489–1499.

Deane R, Sagare A, Zlokovic BV: The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood–brain barrier Abeta clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Pharm Des 2008, 14:1601–1605.

Sagare A, Deane R, Bell RD, Johnson B, Hamm K, Pendu R, Marky A, Lenting PJ, Wu Z, Zarcone T, Goate A, Mayo K, Perlmutter D, Coma M, Zhong Z, Zlokovic BV: Clearance of amyloid-beta by circulating lipoprotein receptors. Nat Med 2007, 13:1029–1031.

Mühl H, Pfeilschifter J: Anti-inflammatory properties of pro-inflammatory interferon-gamma. Int Immunopharmacol 2003, 3:1247–1255.

Lam L, Whitsett CF, McNicholl JM, Hodge TW, Hooper J: Immunologically active proteins in intravenous immunoglobulin. Lancet 1993, 342:678.

Grosse-Wilde H, Blasczyk R, Westhoff U: Soluble HLA class I and class II concentrations in commercial immunoglobulin preparations. Tissue Antigens 1992, 39:74–77.

Blasczyk R, Westhoff U, Grosse-Wilde H: Soluble CD4, CD8, and HLA molecules in commercial immunoglobulin preparations. Lancet 1993, 341:789–790.

Claus R, Werner H, Schulze HA, Walzel H, Friemel H: Are soluble monocyte-derived HLA class II molecules candidates for immunosuppressive activity? Immunol Lett 1990, 26:203–210.

Kekow J, Reinhold D, Pap T, Ansorge S: Intravenous immunoglobulins and transforming growth factor beta. Lancet 1998, 351:184–185.

van der Wal EA, Gómez-Pinilla F, Cotman CW: Transforming growth factor-beta 1 is in plaques in Alzheimer and Down pathologies. Neuroreport 1993, 4:69–72.

Wyss-Coray T, Lin C, Yan F, Yu GQ, Rohde M, McConlogue L, Masliah E, Mucke L: TGF-beta1 promotes microglial amyloid-beta clearance and reduces plaque burden in transgenic mice. Nat Med 2001, 7:612–618.

Gelfand EW: Differences between IGIV products: impact on clinical outcome. Int Immunopharmacol 2006, 6:592–599.

Reipert BM, Stellamor MT, Poell M, Ilas J, Sasgary M, Reipert S, Zimmermann K, Ehrlich H, Schwarz HP: Variation of anti-Fas antibodies in different lots of intravenous immunoglobulin. Vox Sang 2008, 94:334–341.

Mikolajczyk MG, Concepcion NF, Wang T, Frazier D, Golding B, Frasch CE, Scott DE: Characterization of antibodies to capsular polysaccharide antigens of Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae in human immune globulin intravenous preparations. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004, 11:1158–1164.

Patrias LM, Klaver AC, Coffey MP, Loeffler DA: Specific antibodies to soluble alpha-synuclein conformations in intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Clin Exp Immunol 2010, 161:527–535.

Dhainaut F, Guillaumat PO, Dib H, Perret G, Sauger A, de Coupade C, Beaudet M, Elzaabi M, Mouthon L: In vitro and in vivo properties differ among liquid intravenous immunoglobulin preparations. Vox Sang 2013, 104:115–126.

Manlhiot C, Yeung RS, Chahal N, McCrindle BW: Intravenous immunoglobulin preparation type: association with outcomes for patients with acute Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010, 21:515–521.

Roifman CM, Schroeder H, Berger M, Sorensen R, Ballow M, Buckley RH, Gewurz A, Korenblat P, Sussman G, Lemm G: Comparison of the efficacy of IGIV-C, 10% (caprylate/chromatography) and IGIV-SD, 10% as replacement therapy in primary immune deficiency. A randomized double-blind trial. Int Immunopharmacol 2003, 3:1325–1333.

Crow AR, Lazarus AH: The mechanisms of action of intravenous immunoglobulin and polyclonal anti-d immunoglobulin in the amelioration of immune thrombocytopenic purpura: what do we really know? Transfus Med Rev 2008, 22:103–1016.

Becker T, Küenzlen E, Salama A, Mertens R, Kiefel V, Weiss H, Lampert F, Gaedicke G, Mueller-Eckhardt C: Treatment of childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with Rhesus antibodies (anti-D). Eur J Pediatr 1986, 145:166–169.

Salama A, Kiefel V, Mueller-Eckhardt C: Effect of IgG anti-Rho(D) in adult patients with chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Am J Hematol 1986, 22:241–250.

Svetlicky N, Ortega-Hernandez OD, Mouthon L, Guillevin L, Thiesen HJ, Altman A, Kravitz MS, Blank M, Shoenfeld Y: The advantage of specific intravenous immunoglobulin (sIVIG) on regular IVIG: experience of the last decade. J Clin Immunol 2013,33(Suppl 1):S27-S32.

Ryan DA, Mastrangelo MA, Narrow WC, Sullivan MA, Federoff HJ, Bowers WJ: Abeta-directed single-chain antibody delivery via a serotype-1 AAV vector improves learning behavior and pathology in Alzheimer's disease mice. Mol Ther 2010, 18:1471–1481.

Käsermann F, Boerema DJ, Rüegsegger M, Hofmann A, Wymann S, Zuercher AW, Miescher S: Analysis and functional consequences of increased Fab-sialylation of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) after lectin fractionation. PLoS One 2012, 7:e37243.

McGeer PL, Akiyama H, Itagaki S, McGeer EG: Activation of the classical complement pathway in brain tissue of Alzheimer patients. Neurosci Lett 1989, 107:341–346.

Webster S, Lue L-F, Brachova L, Tenner AJ, McGeer PL, Terai K, Walker DG, Bradt B, Cooper NR, Rogers J: Molecular and cellular characterization of the membrane attack complex, C5b-9, in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 1997, 18:415–421.

Loeffler DA: Using animal models to determine the significance of complement activation in Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation 2004, 1:18.

Rossi F, Dietrich G, Kazatchkine MD: Anti-idiotypes against autoantibodies in normal immunoglobulins: evidence for network regulation of human autoimmune responses. Immunol Rev 1989, 110:135–149.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are expressed to the Erb family for a donation to the Beaumont Foundation to support the writing of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DAL wrote the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Loeffler, D.A. Intravenous immunoglobulin and Alzheimer’s disease: what now?. J Neuroinflammation 10, 853 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-10-70

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-10-70