Abstract

Background

A high body mass index (BMI) is associated with an increased risk of mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD); however, a low BMI may also be associated with an increased mortality risk. There is limited information on the relation of incident CHD risk across a wide range of BMI, particularly in women. We examined the relation between BMI and incident CHD overall and across different risk factors of the disease in the Million Women Study.

Methods

1.2 million women (mean age = 56 years) participants without heart disease, stroke, or cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) at baseline (1996 to 2001) were followed prospectively for 9 years on average. Adjusted relative risks and 20-year cumulative incidence from age 55 to 74 years were calculated for CHD using Cox regression.

Results

After excluding the first 4 years of follow-up, we found that 32,465 women had a first coronary event (hospitalization or death) during follow-up. The adjusted relative risk for incident CHD per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI was 1.23 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.25). The cumulative incidence of CHD from age 55 to 74 years increased progressively with BMI, from 1 in 11 (95% CI 1 in10 to 12) for BMI of 20 kg/m2, to 1 in 6(95% CI 1 in 5 to 7) for BMI of 34 kg/m2. A 10 kg/m2 increase in BMI conferred a similar risk to a 5-year increment in chronological age. The 20 year cumulative incidence increased with BMI in smokers and non-smokers, alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers, physically active and inactive, and in the upper and lower socioeconomic classes. In contrast to incident disease, the relation between BMI and CHD mortality (n = 2,431) was J-shaped. For the less than 20 kg/m2 and ≥35 kg/m2 BMI categories, the respective relative risks were 1.27 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.53) and 2.84 (95% CI 2.51 to 3.21) for CHD deaths, and 0.89 (95% CI 0.83 to 0.94) and 1.85 (95% CI 1.78 to 1.92) for incident CHD.

Conclusions

CHD incidence in women increases progressively with BMI, an association consistently seen in different subgroups. The shape of the relation with BMI differs for incident and fatal disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There is growing concern about the impact of the increasing prevalence of obesity on the burden of coronary heart disease (CHD) [1], which accounts for around 15% of all deaths in the UK, USA, and other developed nations [2–4]. Reducing this obesity-associated CHD burden is likely to require population-level preventive strategies. One such approach suggests shifting the population distribution of a modifiable risk factor downwards to prevent the occurrence of CHD [5], but it is unclear if this approach is relevant for obesity. Most large-scale prospective studies have reported on CHD mortality outcomes, showing increased coronary mortality risks in both high and low BMI groups [6–8]. The relation between BMI and CHD may differ for incident and fatal disease [9–11], but such findings were based on a relatively small number of events. Large-scale studies that reported on incident CHD outcomes have been limited, particularly in women, and have not compared findings for incident and fatal CHD [12–17]. It is also unclear if the relation between BMI and incident CHD varies by age [8, 15] or by lifestyle risk factors, particularly smoking [15, 18, 19]. Large-scale prospective studies may be needed to provide reliable risk estimates for incident CHD across a wide range of BMI in the whole population and across important subgroups. To address these questions, we examined the relation between BMI and CHD incidence and mortality in a cohort of over a million women followed for an average of 9 years.

Methods

The Million Women Study is a population-based cohort study that recruited 1.3 million women who were invited for routine breast cancer screening between 1996 and 2001 in England and Scotland by the National Health Service (NHS) screening program [20]. At recruitment, women completed a health and lifestyle questionnaire, which included questions on weight, height, sociodemographic details, medical history, and lifestyle habits. All participants gave their written consent to take part in the study. The Oxford and Anglia Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee approved the conduct of this study.

Using their individual NHS identification number, together with other personal information, participants were linked to NHS Central Registers for information on deaths, cancer registration, and emigrations, and to the NHS hospital admission databases for information on hospital admissions. For participants in England, the Hospital Episode Statistics data were available from 1 April 1997; for participants in Scotland, the Scottish Morbidity Records [21, 22] data were available from 1 January 1981. Hospital diagnoses and causes of death were coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [23] (ICD-10).

Calculation, definition, and validation of anthropometric variables

We used BMI (weight (kg) divided by height (m2), and rounded to the nearest tenth) as our primary measure of adiposity, as it is strongly correlated with total fat mass [24] and provides a comparable explanatory power of the physiologic effect of total fat mass [25]. Overweight and obesity were defined as a BMI of 25 to 29.9 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively. Self-reported weight and height were used to calculate BMI, and two different sources were used to validate the self-reported measures. We identified 541 women who were also participants in another longitudinal study and for whom their weight and height had been measured at the age of 53 years (at around the time that they reported their weight and height to us), and the correlation between BMI calculated from the measured and the self-reported data was 0.90 [26]. A sample of 3,745 women had their weight and height measured at general practice clinics in 2006 and 2008. BMI calculated from self-reported weight and height at baseline on average was 1.4 ± 2.5 kg/m2 (mean ± SD) lower than that from the clinical measurements, taken some 8 to 10 years later, and the correlation between them was 0.85. In a sensitivity analysis, we used data from the clinical measurements to evaluate the effect of measurement error, including changes in BMI over time, on risk estimates [27].

Definition and validation of outcomes

We defined an incident CHD event as the first hospital admission after recruitment with a diagnosis of CHD (ICD-10 I20 to I25) or death with CHD as the underlying cause. In a validation study, we randomly selected 796 women with a hospital record of CHD and 864 with no admission for vascular disease [28]. We asked general practitioners (GPs; they hold the medical record of every individual registered with the NHS) to report if these women had been given this diagnosis and to provide us with the relevant clinical information to support this report. An adjudicating team (FLW, DC, BJC, AB, and JG) reviewed the GPs' diagnosis and the clinical information provided to the investigators. The GP diagnosis of CHD was consistent in 92% of 796 women with a hospital record of CHD; in addition to 864 women without vascular disease hospitalization, 98% were confirmed to have had no CHD diagnosis.

Analysis

Of the 1.3 million women recruited into the study, we excluded 78,895 (5.8%) women who reported heart disease or stroke at recruitment or had been admitted to hospital for these conditions before study entry, and 44,803 (3.3%) women who had a previous cancer registration (except non-melanoma skin cancer), as cancer may affect weight. Of the remaining 1.2 million women, we further excluded 64,620 (5%) women for whom BMI values were missing. The remaining 1,178,939 women formed the basis for our analysis.

We used Cox regression models to calculate hazard ratios to estimate relative risks of CHD separately for incident and mortality outcomes, using attained age as the underlying time variable. Person-years were calculated from date of recruitment until date of first admission for CHD, death, or end of follow-up, whichever came first. Around 5% of participants in England were recruited before 1 April 1997, and as hospital admission data before this date were not available, their follow-up was calculated from this date. The follow-up of women ended on 31 March 2008 in England and 31 December 2008 in Scotland, because hospital admission data were not complete after these dates. The regression models were stratified by region of recruitment (10 regions) and adjusted for smoking (never, past and current smokers with consumptions of less than 5, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, 20 to 24 and ≥25 cigarettes per day), weekly alcohol consumption (0, 1 to 6, 7 to 14 and ≥15 U), strenuous physical activity (rarely/never, once a week or less, and more than once a week), and socioeconomic level (fifths of Townsend deprivation index [29]). There were a few missing values for smoking (0.7%), physical activity (3.0%), alcohol intake (0.6%) and socioeconomic status (0.7%). For each adjustment variable, women with missing values were assigned to a separate category.

We first calculated the incidence rate of CHD for each year of follow-up to examine variations in disease rates over time. Absolute risks of CHD were then calculated as cause-specific cumulative incidences. Within 5-year age groups (55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, and 70 to 74 years), incidence rates were computed from the number of coronary events and time at risk. Hazard ratios from Cox regressions were converted to absolute hazard rates by multiplying the hazard ratios by the overall incidence rate, divided by a weighted average of the BMI category-specific hazard (weights were given by the total person-time at risk for women in the corresponding BMI category) [8]. Cause-specific cumulative incidence over 5 years was calculated for each age and BMI group, where appropriate, from the absolute hazard h (in units of events per person per year) by the formula . The 20-year cause-specific cumulative incidence between the ages of 55 and 74 years was calculated from the simple average of the absolute hazards across the four age groups, , by the formula . We estimated the 20-year cumulative incidence for the whole cohort and by subgroups of women classified by smoking habit, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic status.

We present the risk estimates with their 95% CI. When comparing more than two groups (such as in a figure), relative risks are presented with their 95% group-specific CI (g-sCI) to allow direct comparison between any two groups [30], even if neither is the baseline group. We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the effects of missing values by comparing the relative risks based on data for all women with those women who had no missing values for any covariate, and to evaluate the effects of competing causes of death on the absolute risk estimates [31]. All analyses used Stata 12.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) [32].

Results

The characteristics of the 1,178,939 women included in the analyses are shown in Table 1. The mean age of women at recruitment was 56.0 ± 4.8 years (25th to 75th percentile range 52 to 60) and the mean BMI was 26.1 ± 4.6 kg/m2. The proportions of overweight and obese women at baseline were 35.3% and 17.1%, respectively, with 5.4% having a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or over. Mean alcohol consumption of alcohol drinkers was 4.2 ± 5.4 U/week. Compared with women with a BMI of 20 to 24.9 kg/m2, women with higher BMI were less likely to smoke, consume alcohol, or be physically active, and more likely to have a lower socioeconomic status (Table 1). Women with a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2 were more likely to smoke and to have a lower socioeconomic status, but less likely to drink alcohol or to be physically active, than women with a BMI of 20 to 24.9 kg/m2.

After an average of 9 years of follow-up, there were 48,842 first coronary events including 5,097 CHD deaths. The annual incident CHD rates for the first 4 years of follow-up were slightly lower than the rates in the remaining follow-up period (see Additional file 1, Figure S1). To reflect the usual disease rates in the cohort, and to reduce the possibility of reverse causation (that preclinical disease might affect weight), we excluded the first 4 years of follow-up in all our subsequent analyses. In the remaining approximately 5 years of follow-up, there were 32,465 women with a first coronary event and 2,431 women who had CHD recorded as the underlying cause of death, corresponding to rates of 5.49 (95% CI 5.44 to 5.55) and 0.41 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.42) per 1,000 person-years, respectively.

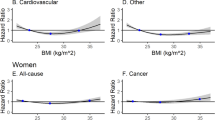

From the lowest BMI categories of less than 20 kg/m2 and 20 to 22.4 kg/m2, the relative risk of incident CHD increased progressively with BMI (Figure 1). The relative risk for incident CHD per increment of 5 kg/m2 in BMI was 1.29 (95% CI 1.28 to 1.30) after adjustment for age and stratification by region. Additionally adjusting for smoking habit, physical activity, alcohol consumption and socioeconomic class slightly attenuated the relative risk to 1.23 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.25). For CHD mortality, the relationship with BMI was J-shaped, and the pattern of risk differed from that of incident disease, with the relative risk being greater for CHD mortality than for incident outcomes among women in the lowest and highest categories of BMI. Compared with a BMI of 22.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, the relative risk of a BMI of less than 20 kg/m2 for CHD mortality was significantly raised at 1.27 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.53), but for incident coronary event was significantly reduced at 0.89 (95% CI 0.83 to 0.94). For BMI ≥35 kg/m2, the relative risk of 2.84 (95% CI 2.51 to 3.21) for CHD mortality was considerably greater than the relative risk of 1.85 (95% CI 1.78 to 1.92) for incident disease.

Adjusted relative risk (95% group-specific confidence interva; g-sCI) for coronary heart disease (CHD) incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index (BMI). Relative risks (RRs) are plotted against mean BMI in the corresponding BMI category. RR = 1.0 for women with BMI of 22.5 to 24.9 kg/m2. CHD cumulative incidence and mortality over 20 years from the age of 55 years. Spaces are provided between incidence and mortality RRs within each BMI category to distinguish their corresponding CIs.

The incidence of CHD increased with age, and the progressive increase in risk with BMI was evident in each 5-year age group from 55 to 59 years to 70 to 74 years (Figure 2; see Additional file 1, Table S1 for further details). Moreover, a BMI increase of 10 kg/m2 conferred an additional CHD risk similar to that conferred by a 5-year increase in age. The 20-year cumulative incidence of the disease was 12.1% (95% CI 11.9 to 12.2), that is, about one in eight women (12%) in this cohort had a first coronary event in the 20 years from age 55 to 74 years. Within the range of 20 to 34.9 kg/m2 (n = 28,866 incident coronary events), there was a sufficient number of events to show that the incidence increased in a graded manner with small increments in BMI (see Additional file 1, Figure S2). The 20-year cumulative incidence of the disease for a BMI of 34 kg/m2 was almost twice that for a BMI of 21 kg/m2 (16.7% (95% CI 13.9 to 19.4%) versus 9.2% (95% CI 8.1 to 10.3%)). This means that around 1 in 6 (95% CI 1 in 5 to 7) women with a BMI of 34 kg/m2, compared with 1 in 11 (95% CI 1 in 10 to 12) women with a BMI of 21 kg/m2, had a first coronary event over a 20-year period from age 55 years.

Assessing the relation between BMI and 20-year cumulative incidence of CHD from age 55 to 74 years by smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and socioeconomic status, the increasing incidence of the disease associated with rising BMI levels was apparent in all subgroups (Figure 3; see Additional file 1, Table S2 for further details). Of all factors examined, current smoking had the greatest effect on CHD incidence. Current smokers who were neither overweight nor obese had similar CHD risks to severely obese never smokers: the cumulative incidence was 16.1% (95% CI 14.9 to 17.3%) for current smokers with BMI less than 25 kg/m2 (mean BMI = 22.6 kg/m2) and 14.9% (95% CI 12.8 to 16.9%) for never smokers with BMI of 35 kg/m2 or over (mean BMI = 38.7 kg/m2). The greatest cumulative risk of CHD from age 55 to 74 years was seen for current smokers with BMI of 35 kg/m2 or over (26.9% (95% CI 21.1 to 32.4%)), suggesting that about 1 in every 4 such women (95% CI 1 in 3 to 5) had a first coronary event in the 20-year period from the age of 55 years. The effect of obesity was also apparent for alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers alike, with the greatest cumulative CHD risk found for non-drinkers with BMI of 35 kg/m2 or over, and the lowest for drinkers with BMI of less than 25 kg/m2.

Correction for measurement error and changes in BMI over time had little effect on the relative risk estimates associated with increasing BMI (see Additional file 1, Table S3). The relative risk for incident CHD per 5-unit increase in BMI was 1.23 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.25) before and 1.24 (95% CI 1.23 to 1.26) after the correction was applied. Limiting the analysis to women with no missing value for any covariate had little effect on the relative risk (1.23 (95% CI 1.22 to 1.25)). When we accounted for competing causes of death, the 20-year cumulative risks were only slightly reduced (see Additional file 1, Figure S3).

Discussion

In this large cohort of middle-aged UK women, about one in every eight women will have a first hospital admission for or have died from CHD in the 20 years from the age of 55 to 74 years. The cumulative incidence of CHD over 20 years increased progressively with BMI, from about one in eleven women with a BMI of 21 kg/m2 to one in six women with a BMI of 34 kg/m2. Similar trends of progressively increasing CHD incidence with increasing BMI were seen across the age groups studied, and in smokers and non-smokers, alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers, women who were active and inactive, and in women from upper and lower socioeconomic groups.

Unlike the association between BMI and incident disease, there was a J-shaped relationship between BMI and CHD mortality. Our findings are consistent with findings from other large-scale prospective studies for CHD mortality [6–8, 33] and for all-cause mortality (where a substantial proportion of deaths are due to vascular causes) [6, 8, 34–36]. It is possible that the relation with BMI varies for fatal and incident CHD outcomes [9–11], but these findings have been based on relatively small numbers of disease events. No other large-scale study has directly compared the BMI-CHD relationship for incident and fatal CHD. In our study, the relative risks for those with the lowest and highest BMI values were greater in magnitude for CHD mortality than for incident coronary event, suggesting that case fatality rates are higher in both lean and obese women than in those with a BMI within the normal or overweight range. The underlying reason for the excess vascular deaths associated with low BMI remains unclear. Although we excluded early disease events, reverse causation remains a possibility, as the effect of preclinical illness in those with low BMI on fatal outcomes may persist over a long period [36]. However, this confounding effect was not apparent for incident CHD events as we found no evidence of an increased incidence rate associated with low BMI. Thus, our findings provide evidence for the importance of greater adiposity in the occurrence of a CHD event. In other studies that investigated the association between BMI and incident CHD [9, 12–15, 17, 37], results were broadly similar to those found here, but generally lacked power to describe reliably the relation between BMI and incident CHD across a wide range of values and important subgroups in the population.

BMI is known to vary with a number of factors, including age, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic status [8, 15, 38], which are also associated with CHD risk [2, 3]. We took these potential confounding factors into account in our analyses. Further, our results suggest that obesity remains as important a risk factor for incident disease in older as in younger women in the age group studied. The effect of a 10 kg/m2 increment in BMI on CHD incidence was comparable with that of a 5-year increase in chronological age. We also found that the increasing CHD risk with increasing BMI was consistently seen for current and never smokers, alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers, physically active and inactive women, and women in the upper and lower socioeconomic groups. Few studies have compared the combined effect of obesity and smoking on heart disease [15, 18, 19, 37, 39], and our results indicate a very large absolute risk that one in four current smokers who are also obese will develop a coronary event in the 20 years from the age of 55 years. Women drinkers in this cohort consume only low to moderate amounts of alcohol, and such consumption has been known to be associated with lower CHD risk [40]; nevertheless, CHD risk increased with BMI in both drinkers and non-drinkers.

Our findings could have important implications for public health, and suggest that reducing this obesity-associated CHD burden will probably require population-level preventive strategies. One such approach suggests shifting the population distribution of a modifiable risk factor downwards to prevent the occurrence of CHD [5]. However, shifting the population distribution of BMI downwards may have unintended consequences, considering that large-scale prospective studies that looked at fatal disease have shown increased CHD mortality risks with both high and low BMI levels [6–8]. However, our findings suggest that there is no such increased risk at the lower end of the BMI range for incident outcomes. Because most CHD events occurred in non-obese women, and small increments in BMI were associated with increasing incidence of the disease, small shifts in BMI distribution could potentially have a large effect on reducing the CHD burden both in the whole population and in important subgroups defined by age, smoking, physical activity level, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic class.

There are some limitations to consider in interpreting our findings. We used self-reported weight and height at baseline to calculate BMI, and this can change over time. However, the correlation of measured and self-reported data for BMI is high, and correction for both measurement error and changes over time did not materially alter our results. We assessed only BMI, an indicator of total adiposity, but abdominal adiposity may also confer additional CHD risk [13, 15]. Our findings included women only, but there is little to suggest that the relation between BMI and CHD differs between men and women [14, 15, 37]. However, the absolute risks may not be directly applicable to women in different populations. Allowing for competing causes of death hardly changed the 20-year incidence rates. Further, CHD may be clinically under-diagnosed in women [41]. However, mediating factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia are known to increase with BMI [8, 15] and so the proportion of undiagnosed cases may be higher at the higher than the lower end of the BMI distribution. Thus, our estimates of the relative difference in incidence rates between lower and higher BMI levels are likely to be conservative. Study participants were recruited when they were invited for routine breast cancer screening by a nationwide program. At the time the cohort was recruited, study participants represented one in four of the UK women in the target age range [20], so our findings are likely to be relevant to a large proportion of middle-aged women.

Conclusions

The effect of obesity on CHD was substantial in this cohort of women, and the association was consistently seen in various subgroups defined by their age, smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and socioeconomic class. Because most CHD events occurred in non-obese women, and even small increments in BMI were associated with increasing incidence of the disease, small shifts in the population distribution of BMI may potentially have a large effect on reducing the CHD burden in the population.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CHD:

-

coronary heart disease

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- g-sCI:

-

group-specific confidence interval

- ICD-10:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision

- NHS:

-

National Health Service.

References

Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S: Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 2388-2398. 10.1056/NEJMsa053935.

Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, et al: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2012 Update: a report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012, 125: e2-e220.

Scarborough P, Wickramasinghe K, Bhatnagar P, Smolina K, Mitchell C, Rayner M: Coronary Heart Disease Statistics, 2010 edition. 2010, London: British Heart Foundation

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL: Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. 2006, New York: Oxford University Press

Rose G: Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985, 14: 32-38. 10.1093/ije/14.1.32.

McGee DL: Body mass index and mortality: a meta-analysis based on person-level data from twenty-six observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2005, 15: 87-97. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.012.

Chen Z, Yang G, Zhou M, Smith M, Offer A, Ma J, Wang L, Pan H, Whitlock G, Collins R, Niu S, Peto R: Body mass index and mortality from ischaemic heart disease in a lean population: 10 year prospective study of 220,000 adult men. Int J Epidemiol. 2006, 35: 141-150.

Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R: Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009, 373: 1083-1096. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4.

Logue J, Murray HM, Welsh P, Shepherd J, Packard C, Macfarlane P, Cobbe S, Ford I, Sattar N: Obesity is associated with fatal coronary heart disease independently of traditional risk factors and deprivation. Heart. 2011, 97: 564-568. 10.1136/hrt.2010.211201.

Rosengren A, Wedel H, Wilhelmsen L: Body weight and weight gain during adult life in men in relation to coronary heart disease and mortality. A prospective population study. Eur Heart J. 1999, 20: 269-277. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1235.

Hotchkiss JW, Davies CA, Leyland AH: Adiposity has differing associations with incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Scottish population: cross-sectional surveys with follow-up. Int J Obes (Lond). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.102

Ni Mhurchu C, Rodgers A, Pan WH, Gu DF, Woodward M: Body mass index and cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific Region: an overview of 33 cohorts involving 310 000 participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2004, 33: 751-758.

Canoy D, Boekholdt SM, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Buchan I, Day N, Khaw KT: Body fat distribution and risk of coronary heart disease in men and women in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition in Norfolk cohort: a population-based prospective study. Circulation. 2007, 116: 2933-2943. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.673756.

Flint AJ, Hu FB, Glynn RJ, Caspard H, Manson JE, Willett WC, Rimm EB: Excess weight and the risk of incident coronary heart disease among men and women. Obesity. 2010, 18: 377-383. 10.1038/oby.2009.223.

Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Wood AM, Pennells L, Thompson A, Sarwar N, Kizer JR, Lawlor DA, Nordestgaard BG, Ridker P, Salomaa V, Stevens J, Woodward M, Sattar N, Collins R, Thompson SG, Whitlock G, Danesh J: Separate and combined associations of body-mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet. 2011, 377: 1085-1095.

Stegger JG, Schmidt EB, Obel T, Berentzen TL, Tjonneland A, Sorensen TI, Overvad K: Body composition and body fat distribution in relation to later risk of acute myocardial infarction: a Danish follow-up study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011, 35: 1433-1441. 10.1038/ijo.2010.278.

Nordestgaard BG, Palmer TM, Benn M, Zacho J, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Davey Smith G, Timpson NJ: The effect of elevated body mass index on ischemic heart disease risk: causal estimates from a Mendelian randomisation approach. PLoS Med. 2012, 12: e1001212.

Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH: Weight, weight change, and coronary heart disease in women. Risk within the 'normal' weight range. JAMA. 1995, 273: 461-465. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520300035033.

Impact of cigarette smoking on the relationship between body mass index and coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 3264 stroke and 2706 CHD events in 378579 individuals in the Asia Pacific region. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9: 294.

Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D: Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007, 335: 1134-1144. 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE.

NHS Information Centre: Hospital Episode Statistics. [http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes]

Harley K, Jones C: Quality of Scottish Morbidity Record (SMR) data. Health Bull (Edinb). 1996, 54: 410-417.

World Health Organization: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. [http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en]

Flegal KM, Shepherd JA, Looker AC, Graubard BI, Borrud LG, Ogden CL, Harris TB, Everhart JE, Schenker N: Comparisons of percentage body fat, body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-stature ratio in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89: 500-508. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26847.

Spiegelman D, Israel RG, Bouchard C, Willett WC: Absolute fat mass, percent body fat, and body-fat distribution: which is the real determinant of blood pressure and serum glucose?. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992, 55: 1033-1044.

Cairns BJ, Liu B, Clennell S, Cooper R, Reeves GK, Beral V, Kuh D: Lifetime body size and reproductive factors: comparisons of data recorded prospectively with self reports in middle age. BMC medical research methodology. 2011, 11: 7-10.1186/1471-2288-11-7.

Rosner B, Willett WC, Spiegelman D: Correction of logistic regression relative risk estimates and confidence intervals for systematic within-person measurement error. Stat Med. 1989, 8: 1051-1069. discussion 1071-1053

Wright FL, Green J, Canoy D, Cairns BJ, Balkwill A, Beral V, For the Million Women Study C: Vascular disease in women: comparison of diagnoses in hospital episode statistics and general practice records in England. BMC medical research methodology. 2012, 12: 161-10.1186/1471-2288-12-161.

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A: Health and deprivation: inequality and the north. 1988, Beckenham: Croom Helm

Plummer M: Improved estimates of floating absolute risk. Stat Med. 2004, 23: 93-104. 10.1002/sim.1485.

Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H: Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012, 41: 861-870. 10.1093/ije/dyr213.

Stata MP: 2011, College Station, TX: StataCorp, Version 12.0.

Morkedal B, Romundstad PR, Vatten LJ: Mortality from ischaemic heart disease: age-specific effects of blood pressure stratified by body-mass index: the HUNT cohort study in Norway. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011, 65: 814-819. 10.1136/jech.2009.094110.

Calle EE, Thun MJ, Petrelli JM, Rodriguez C, Heath CW: Body-mass index and mortality in a prospective cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1999, 341: 1097-1105. 10.1056/NEJM199910073411501.

Jee SH, Sull JW, Park J, Lee SY, Ohrr H, Guallar E, Samet JM: Body-mass index and mortality in Korean men and women. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355: 779-787. 10.1056/NEJMoa054017.

Berrington de Gonzalez A, Hartge P, Cerhan JR, Flint AJ, Hannan L, MacInnis RJ, Moore SC, Tobias GS, Anton-Culver H, Freeman LB, Beeson WL, Clipp SL, English DR, Folsom AR, Freedman DM, Giles G, Hakansson N, Henderson KD, Hoffman-Bolton J, Hoppin JA, Koenig KL, Lee IM, Linet MS, Park Y, Pocobelli G, Schatzkin A, Sesso HD, Weiderpass E, Willcox BJ, Wolk A, et al: Body-mass index and mortality among 1.46 million white adults. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363: 2211-2219. 10.1056/NEJMoa1000367.

Jee SH, Pastor-Barriuso R, Appel LJ, Suh I, Miller ER, Guallar E: Body mass index and incident ischemic heart disease in South Korean men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005, 162: 42-48. 10.1093/aje/kwi166.

Canoy D, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Day N, Khaw KT: Cigarette smoking and fat distribution in 21,828 British men and women: a population-based study. Obes Res. 2005, 13: 1466-1475. 10.1038/oby.2005.177.

Willett WC, Green A, Stampfer MJ, Speizer FE, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Monson RR, Stason W, Hennekens CH: Relative and absolute excess risks of coronary heart disease among women who smoke cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 1987, 317: 1303-1309. 10.1056/NEJM198711193172102.

Ronksley PE, Brien SE, Turner BJ, Mukamal KJ, Ghali WA: Association of alcohol consumption with selected cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011, 342: d671-10.1136/bmj.d671.

Bairey Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Rogers WJ, Pohost GM, Lerman A, Quyyumi AA, Sopko G: Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part II: gender differences in presentation, diagnosis, and outcome with regard to gender-based pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and macrovascular and microvascular coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47: S21-29. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.084.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/87/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in the Million Women Study. We thank Adrian Goodill for preparation of the figures, and we also thank the Information Services Division in Scotland and the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care in England for the hospital admission data.

The co-ordinating centre staff for the Million Women Study are: Simon Abbott, Naomi Allen, Miranda Armstrong, Angela Balkwill, Emily Banks, Vicky Benson, Valerie Beral, Judith Black, Anna Brown, Diana Bull, Benjamin J Cairns, Kathy Callaghan, Karen Canfell, Dexter Canoy, James Chivenga, Barbara Crossley, Francesca Crowe, Dave Ewart, Sarah Ewart, Lee Fletcher, Toral Gathani, Laura Gerrard, Adrian Goodill, Jane Green, Lynden Guiver, Isobel Lingard, Elizabeth Hilton, Sau Wan Kan, Carol Keene, Oksana Kirichek, Mary Kroll, Nicky Langston, Bette Liu, Maria-Jose Luque, Lynn Pank, Kirstin Pirie, Gillian Reeves, Andrew Roddam, Keith Shaw, Emma Sherman, Evie Sherry-Starmer, Helena Strange, Sian Sweetland, Alison Timadjer, Sarah Tipper, Ruth Travis, Xiaosi Wang, Joanna Watson, F Lucy Wright, Owen Yang, and Heather Young.

The steering committee members are: Emily Banks, Valerie Beral, Ruth English, Jane Green, Julietta Patnick, Richard Peto, Gillian Reeves, Martin Vessey, and Matthew Wallis.

The following NHS Breast Screening Centres took part in the recruitment and breast screening follow-up for the Million Women Study: Avon, Aylesbury, Barnsley, Basingstoke, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, Cambridge and Huntingdon, Chelmsford and Colchester, Chester, Cornwall, Crewe, Cumbria, Doncaster, Dorset, East Berkshire, East Cheshire, East Devon, East of Scotland, East Suffolk, East Sussex, Gateshead, Gloucestershire, Great Yarmouth, Hereford and Worcester, Kent, Kings Lynn, Leicestershire, Liverpool, Manchester, Milton Keynes, Newcastle, North Birmingham, North East Scotland, North Lancashire, North Middlesex, North Nottingham, North of Scotland, North Tees, North Yorkshire, Nottingham, Oxford, Portsmouth, Rotherham, Sheffield, Shropshire, Somerset, South Birmingham, South East Scotland, South East Staffordshire, South Derbyshire, South Essex, South Lancashire, South West Scotland, Surrey, Warrington Halton St Helens and Knowsley, Warwickshire Solihull and Coventry, West Berkshire, West Devon, West London, West Suffolk, West Sussex, Wiltshire, Winchester, Wirral, and Wycombe.

The Million Women Study is funded by Cancer Research UK, the Medical Research Council, and the NHS Breast Screening Programme. The funding organizations were not involved in the study design or conduct, data analysis or interpretation, manuscript preparation or review, final version approval, or decision to submit the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

VB, GR, and JG were involved in the conception, design, and data acquisition for the Million Women Study. DC, BJC, AB, FLW, and VB analyzed and interpreted the data. DC drafted the first version of the manuscript. BJC, AB, FLW, JG, GR, and VB gave critical intellectual input and contributed to drafting revised versions of the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval of the version to be published.

Electronic supplementary material

12916_2012_777_MOESM1_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Body mass index and annual coronary heart disease (CHD) incidence (95% confidence interval) in relation to year of follow-up from baseline. Table S1. Cumulative incidence (95% confidence interval) of coronary heart disease in relation to body mass index and attained age (supplement for Figure 2). Figure S2. The 20-year cumulative incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) from age 55 to 74 years in relation to body mass index. Table S2. Number of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events in relation to body mass index and other risk factors (supplement for Figure 3). Table S3. Relative risk (95% confidence interval (CI)) of coronary heart disease per 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index and correction for measurement error by regression calibration. Figure S3. The 20-year cumulative incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) (cause-specific and with competing causes of deaths) from age 55 to 74 years in relation to body mass index. (DOCX 227 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Canoy, D., Cairns, B.J., Balkwill, A. et al. Body mass index and incident coronary heart disease in women: a population-based prospective study. BMC Med 11, 87 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-87

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-87