Abstract

Alterations in several biological systems, including the neuroendocrine and immune systems, have been consistently demonstrated in patients with major depressive disorder. These alterations have been predominantly studied using easily accessible systems such as blood and saliva. In recent years there has been an increasing body of evidence supporting the use of peripheral blood gene expression to investigate the pathogenesis of depression, and to identify relevant biomarkers. In this paper we review the current literature on gene expression alterations in depression, focusing in particular on three important and interlinked biological domains: inflammation, glucocorticoid receptor functionality and neuroplasticity. We also briefly review the few existing transcriptomics studies. Our review summarizes data showing that patients with major depressive disorder exhibit an altered pattern of expression in several genes belonging to these three biological domains when compared with healthy controls. In particular, we show evidence for a pattern of 'state-related' gene expression changes that are normalized either by remission or by antidepressant treatment. Taken together, these findings highlight the use of peripheral blood gene expression as a clinically relevant biomarker approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a complex disorder characterized by the interaction between biological, genetic and environmental factors, and by a pathogenesis involving alterations in several biological systems. A large amount of research has been focused on understanding the underlying mechanisms of MDD, and there is already a wealth of evidence demonstrating changes not only in the central nervous system (CNS) but also in the periphery. For example, blood and saliva are useful and accessible systems that, via relatively low-invasive procedures, can be used to analyze several biomarkers, such as proteins or metabolites, using quantitative techniques. Using this approach, hormonal and immunological abnormalities, such as elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [1, 2], alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [3], changes in neuroplasticity [4], and changes in oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways [5], have all been documented in patients with MDD, and are indicative of the 'neuroprogressive' nature of MDD [6].

An emerging and useful method to investigate the pathogenesis of this disorder is the use of peripheral blood to measure the expression levels of genes. This is a useful approach in biomarker identification, with opportunities for both hypothesis-driven biomarker search and for hypothesis-free transcriptomics-based discovery [7]. 'Blood gene expression' usually refers to intracellular RNA from blood, and it is technically associated, in most cases, with two approaches: the use of tubes for blood collection that stabilize mRNA from all cells in the blood; and the extraction of mRNA from separate distinct blood cell populations. What is really of importance for researchers is whether blood mRNA can be used as a proxy for mRNA expression in other tissues that are more relevant to the pathogenic processes of interest - in psychiatry and neuroscience, the brain. In this regard, peripheral blood gene expression is very promising, as several studies have shown that blood cells share more than 80% of the transcriptome with other body tissues, including the brain [8]. For example, Sullivan and colleagues compared the transcriptional profiling of 79 human tissues, including that of whole blood and of several brain areas. They showed that whole blood shares significant gene expression similarities with multiple brain tissues, in particular for genes encoding for neurotransmitter receptors and transporters, stress mediators, cytokines, hormones, and growth factors, all of which are relevant to MDD [9]. As such, investigating peripheral blood gene expression appears to be a useful tool for assessing and understanding MDD.

It is important to mention that biomarker researchers have previously used the term leukocyte gene expression to refer to blood gene expression, implying that the mRNA isolated from blood comes predominantly from leukocytes (white blood cells) - that is, the cells of the immune system. This assumption has been largely based on the notion that erythrocytes, or red blood cells, even if much more abundant than leukocytes (by a factor of approximately 1,000), do not have a nucleus and as such should not have mRNA synthesis. However, most recent research has suggested that, in fact, whole blood mRNA comes predominantly from erythrocytes [7].

As mentioned above, there is clear evidence that biological systems such as the HPA axis and the inflammatory response are altered and can contribute to the pathogenesis of depression [10, 11]. The dysfunction of these systems is largely thought to be a result of the activation of stress-related mechanisms, as MDD is often preceded by acute or chronic stressful experiences [12]. We and others have proposed an explanatory model centered on the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), one of the most important receptors and transcription factors governing the stress response [3]. Stress can induce glucocorticoid resistance, that is, a reduction of GR function, which in turn leads to both HPA axis hyperactivity and increased inflammation. As communication occurs between the CNS and the endocrine and immune systems, an activation of one can affect the processes of another, and vice versa [13]. Based on this, we review the current literature on blood gene expression alterations in MDD. Additionally, we look at bipolar disorder (BPD) studies that consider euthymic or depressed states, but excluding those that look at manic states. We focus in particular on three important and interlinked domains: inflammation, GR functionality and neuroplasticity. We also briefly review the few existing transcriptomics studies.

Alterations in the expression of genes involved in inflammation

The inflammatory theory of MDD emphasizes the role of psychoneuroimmunological dysfunctions where there is an activation of the immune system [14–17]. Moreover, MDD is very common in the medically ill, particularly in conditions with an inflammatory component, such as cardiovascular disease and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as in autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders [18, 19]. Indeed, patients with MDD have been consistently shown to have altered levels of pro- and anti- inflammatory cytokines in circulation [1, 2, 20], and postmortem studies have also described gene expression alterations in a variety of these cytokines [21]. However, studies on postmortem brains have several limitations that can affect the results, including the brain region analyzed, the cause of death and the effect of the antidepressant treatments on gene expression. As such, researchers are using peripheral tissues, such as leukocytes, that have several advantages, which we have already mentioned [9]. A few studies have assessed the mRNA levels of genes involved in inflammation in the peripheral blood of patients with MDD (see Table 1). For example, Tsao and colleagues found that the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ genes was significantly higher in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with MDD compared with healthy controls [22]. Moreover, in a sub-sample of patients, they demonstrated that IFN-γ expression was reduced, though not normalized, after 3 months of fluoxetine treatment, suggesting that antidepressants may have anti-inflammatory properties. Similarly, we have recently shown altered gene expression levels in a number of cytokines in the whole blood of patients with MDD when compared with controls [23]. We have found higher mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and macrophage inhibiting factor (MIF) as well as lower levels of IL-4. Moreover, we have also found that IL-β, TNF-α and MIF mRNA levels are predictors of antidepressant treatment response, as all three show higher baseline expression in non-responders. Finally, we also demonstrated that IL-6 expression is reduced after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment (escitalopram or nortriptyline) in responders only, suggesting a unique ability of these biomarkers to both predict and track the therapeutic antidepressant response.

The activation of the immune system observed in patients with MDD is of course not limited to changes in cytokines production. For example, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a protein produced by macrophages known to act as an immunomodulator. ApoE is thought to interact with many immunological processes including suppression of T cell proliferation, macrophage function regulation and activation of natural killer T cells [24]. One study investigated the expression levels of the ApoE receptor, ApoER2, in lymphocytes of patients with MDD and healthy controls [25], demonstrating that patients with MDD had a significantly lower expression of ApoER2 compared with controls. These receptors bind to reelin, an extracellular matrix glycoprotein that plays crucial roles in brain development as well as in synaptic plasticity in the adult brain [26]. Interestingly, blood levels of an isoform of reelin have also been shown to be reduced in patients with MDD [27].

There is also gene expression evidence for the involvement of key inflammatory enzymes, including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), myeloperoxidase (MPO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase, in the development of MDD [28–30]. These enzymes have been shown to be expressed not only in immune cells but also in the CNS. Moreover, increased oxidative and nitrosative stress as sequels of inflammation have been previously demonstrated postmortem as well as in animal studies [5, 31]. Indeed, a gene expression study showed higher mRNA levels of COX-2, MPO, inducible nitric oxide synthase-2A and phospholipase A2 (PLA2G2A) in patients with MDD compared with healthy controls [32]. Furthermore, an increase in either reductive or oxidative stress is thought to be involved in the alteration of the expression of several neurotrophic factors, and will be reviewed below (see neuroplasticity).

Finally, a recent study in patients with MDD and euthymic BPD disorder investigated three key genes involved in inflammatory processes: triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (TREM-1), DNAX-activation protein of 12 kDa (DAP12), and purine-rich Box-1 (PU.1) [33]. In this study, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from whole blood and gene expression carried out using purified monocytes. The results showed a significantly higher expression of PU.1 in patients with MDD and a significantly higher expression of TREM-1 in patients with BPD, with a trend for higher expression in patients with MDD compared with healthy controls, supporting, again, the role of inflammation in these disorders.

Alterations in the expression of genes involved in glucocorticoid receptor functionality

Alterations of the HPA axis, including impairments in glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback, is a well-established and consistent finding in MDD [34]. The GR is involved in this negative feedback and several studies have assessed GR expression and functionality in patients with MDD. These studies have primarily been conducted in peripheral cell types including immune cells (mononuclear and polymorphonuclear leukocytes) and fibroblasts (gingival and skin) [34]. Four studies have analyzed mRNA expression of GR or of GR-related molecules in peripheral blood (see Table 2). Katz et al. [35] investigated gene expression of chaperones and co-chaperones of the GR, such as FK506 binding protein (FKBP)-4 and FKBP-5, which influence GR function, and of GR target genes during pregnancy in individuals with a history of depression. They found an upregulation of eight genes during pregnancy in all patients; however, the expression of BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 1 (BAG1), FKBP-5, peptidylprolyl isomerase D (PPID) and nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1) was reduced in mothers who were in a current depressive state. This suggests that maternal depression diminishes the pregnancy-related upregulation of these particular GR-related genes [35]. A part of these findings was replicated in our recent study, where we also assessed the expression of FKBP-4, FKBP-5 and GR in patients with MDD and controls [23]. We found higher mRNA levels of FKBP-5 and lower levels of GR in patients with MDD compared with controls. Furthermore, we found that antidepressant treatment significantly reduces FKBP-5 levels after 8 weeks in patients who responded to treatment, and increases GR levels in all patients, suggesting that a successful antidepressant treatment requires a normalization of GR function.

In a third study, Matsubara et al. [36] investigated two isoforms of GR in both patients with MDD and with BPD: GRα, which is able to directly exert glucocorticoid effects, and GRβ, which binds poorly to glucocorticoids and, by forming heterodimers with GRα, impairs ligand binding of this isoform and acts as a dominant negative regulator of GR function [36]. The authors found that GRα expression was lower in patients with MDD and with BPD, in both current depressive states and in remission, compared with healthy controls. This suggests that GRα mRNA reduction is not state-dependent but a trait-dependent finding in mood disorders. These findings may seem at odds with the aforementioned study showing that antidepressant treatment increases GR expression [23]; however, it is important to note that most of the patients with depression in the study by Matsubara et al., even those defined as 'currently depressed', were already on antidepressants at the time of the gene expression analysis. They found no significant differences in the expression of GRβ in either patient groups compared with controls. Lastly, a study conducted by the same group, again in both patients with MDD and with BPD, investigated glyoxalase-1 (Glo1) [37], an antioxidant enzyme involved in oxidative stress and also a GR target gene as it contains consensus sequences for GR response elements [38]. It has been suggested that a GR dysfunction may also have an effect on Glo1 expression and, indeed, the authors found a lower expression of Glo1 in patients with MDD and BPD in a current depressive state compared with controls. On the contrary, there was no significant difference in Glo1 expression in patients with MDD or BPD in remission when compared with controls. This supports the notion that a reduced GR function, and thus a reduced expression of GR target genes like Glo1, is involved in the pathogenesis of depression, and that antidepressant treatment is able to restore this dysfunction. These data are also consistent with our experimental work showing that antidepressant treatment increases GR function both in vivo [39–42] and in vitro [43, 44].

Alterations in the expression of genes involved in neuroplasticity

MDD may also involve an inability of neuronal systems, especially under stress conditions, to show adaptive plasticity, a mechanism known as neuronal plasticity [4] (see Table 3). Molecular correlations underlying the mechanisms of the stress response involve the regulation of several neurotrophic factors, one of them being brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). To this regard, several studies have demonstrated reduced serum and plasma BDNF levels in patients with MDD when compared with controls, and now a few studies have investigated BDNF at gene expression level. Pandey et al. [45] investigated BDNF gene expression in both adult and pediatric patients with MDD and found significantly lower mRNA expression as well as lower protein levels in both MDD groups compared with controls [45]. These findings are supported by another of our studies, where we have also shown significantly lower BDNF expression in the peripheral leukocytes of patients with MDD compared with controls [46]. Additionally, we have found a significant increase in BDNF expression after treatment with the antidepressant escitalopram as well as a parallel improvement in depressive symptoms. In a similar study, we investigated the expression of the neuropeptide VGF (non-acronymic) in the peripheral leukocytes of patients with MDD and controls. VGF is known to be involved in synaptic plasticity and to be induced by BDNF [47], and we have shown that VGF expression is significantly lower in patients with MDD compared with controls [48]. Interestingly, we also found that expression of VGF is increased after 12 weeks of escitalopram treatment in those patients whose depressive symptoms were ameliorated. We have recently replicated these data in the aforementioned larger study [23], where again we show that patients with MDD have lower mRNA levels of BDNF and VGF, and that antidepressant treatment (escitalopram or nortriptyline) increases both BDNF and VGF expression in treatment responders.

In a study of patients with MDD and BPD, Otsuki et al. did not find any significant differences in BDNF expression between patients and controls [49]. However, most of the patients were on antidepressant medication, so this may explain the lack of differences. Moreover, Otsuki and colleagues showed state-dependent differences in a number of other neurotrophic factors, including glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), artemin (ARTN) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3). These factors have previously been shown to be associated with stress response in animal models [50] as well as with depression and suicide in humans [51]. Specifically, they demonstrated that patients with MDD in a current depressive state have lower expression of GDNF, ARTN and NT-3 compared with those in remission as well as controls. However, they did not find any significant differences in the expression levels of these three factors in BPD patients in depressive or remissive states, suggesting that the changes in the expression of these genes are associated with MDD only, and may be state-dependent.

Another protein related to BDNF is p11, a member of the S-100 family known to be involved in the regulation of a number of cellular processes such as cell cycle progression and differentiation [52, 53]. Interestingly, two studies have found p11 to be overexpressed in patients compared with healthy controls. Su et al. demonstrated that patients with MDD had a higher expression of p11 compared with controls [54], and Zhang et al. found the same results in patients with BPD [55]. However, in both of these studies the patients were medicated. Conversely, in our recent study we reported lower mRNA levels of p11 in drug-naïve patients with MDD compared with controls [23]. Furthermore, after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment, p11 levels were significantly increased. We have also recently demonstrated that p11 mRNA levels are increased by antidepressant treatment in vitro in a human neuronal hippocampal model [43], thus showing also the unique ability of a gene expression approach to be used consistently across different experimental approaches.

As mentioned earlier, the expression of neurotrophic factors can be altered particularly in response to oxidative or reductive stress. One such neurotrophic factor is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Increased expression of VEGF has previously been shown in peripheral monocytes of patients with diabetes with coronary artery disease [56]. Given the high prevalence of depression in patients with coronary artery disease, VEGF mRNA levels have been proposed as a putative biological marker for MDD. Indeed, Iga and colleagues measured VEGF expression in the peripheral leukocytes of patients with MDD and showed that VEGF expression was higher in patients with MDD compared with healthy controls [57]. A similar study by Dome et al. [58] investigated the expression levels of VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2) in the peripheral blood of patients with MDD. They showed a lower expression of VEGFR2 in patients with MDD compared with healthy controls. Moreover, the expression of VEGFR2 negatively correlated with depression scores, thus supporting the role of VEGF signaling in MDD pathogenesis [58].

Two further molecules regulating neurogenesis have been found to be altered in depression: pericentrin 2 (PCNT2) and epithelial membrane protein 1 (EMP1). PCNT2 is a disrupted in schizophrenia 1-interacting protein that regulates cell proliferation, differentiation and migration, and outgrowth of neuronal axons and dendrites. In a study of patients with MDD and BPD, mRNA levels of PCNT2 were found to be significantly higher in drug-naïve patients with MDD compared with controls [59]. Interestingly, PCNT2 expression was also higher in patients with BPD in a remission state when compared with controls. EMP1 is involved in neurogenesis mechanisms as it interacts with transforming growth factor beta signaling. In drug-naïve patients with MDD, EMP1 levels were significantly lower when compared with controls and, after 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment, EMP1 mRNA levels showed a trend towards an increase [60].

Cell adhesion molecules such as neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and L1 are also known to play important roles in synaptic plasticity, and have been indicated to have altered expression in the cerebrospinal fluid and brain of patients with a mood disorder [61–63]. Several studies conducted in peripheral blood mRNA confirm this. For example, Wakabayashi et al. [64] assessed the expression of NCAM-140 and L1 in the leukocytes of patients with MDD and BPD, as well as controls. They found a lower expression of NCAM-140 in patients with BPD in a current depressive, but not in a remissive, state compared with both controls and patients with MDD [64]. They also found a higher expression of L1, again in patients with BPD in a depressive state but not in those in remission compared with controls and patients with MDD. Interestingly, they did not find any significant differences in the expression of these molecules in patients with MDD when compared with controls. This suggests that the alterations in the expression of both NCAM-140 and L1 are specific to BPD and are also state dependent. In addition, no changes were found for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) or E-cadherin expression, in patients with either MDD or BPD compared with controls.

Repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor (REST) is a modulator protein that is also known to be involved in synaptic plasticity [65]. It has been recently shown that REST is involved in the synthesis of cortisol [66] and in neurogenesis [67], both of which are of relevance to mood disorders. Otsuki and colleagues investigated the expression of REST and a variety of its target genes including corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), adenylate cyclise 5 (Adcy5) and TNF superfamily member 12-13 (TNFsf12-13) in patients with MDD and BPD [68]. They found a lower expression of REST in patients with MDD compared with controls. Furthermore, they investigated whether altered expression of these mRNAs were state or trait dependent, reporting a higher expression of CRH, Adcy5 and TNFsf12-13 in patients with MDD in a current depressive state compared with those in a remissive state. Interestingly, they found no significant differences in the expression of REST or any other mRNAs in patients with BPD when compared with controls.

Transcriptomics studies

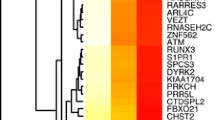

The use of high-throughput technologies like microarray platforms allows for the exploration of the expression levels of the entire genome and thus the identification of gene expression differences by using a hypothesis-free approach (See Table 4). Beech et al. used microarrays containing >48,000 transcript probes to investigate gene expression in the peripheral blood of patients with BPD compared with healthy controls [69]. They found a total of 1,180 differentially expressed genes, 559 of which were upregulated in patients with BPD and 621 that were downregulated. Using pathway analysis they were able to identify functional pathways that were significantly different between patients and controls, including pathways involved in gene transcription, immune response, apoptosis and cell survival. In particular, they found differences in the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signaling pathway, which plays important roles in transcription regulation and immune response mechanisms. This is in line with a previous study showing increased DNA binding of NF-κB in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with MDD in response to an acute stressor [70]. Another microarray study focusing on postpartum depression identified 73 differentially expressed genes in mothers with postpartum depression compared with control mothers [71]. Of interest, the authors observed a reduction in the expression of genes involved in immune modulation, transcriptional activation, cell cycle and proliferation, as well as DNA replication and repair processes. As previously mentioned, neuronal plasticity as well as cell survival are important processes involved in MDD and even in the effects of antidepressant drugs [72]. Indeed, one microarray study investigated gene expression changes in response to the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine in elderly patients with MDD [73]. The authors found 57 out of 8,000 sequences examined to have an altered expression after 4 weeks of antidepressant treatment. The genes found to be differentially expressed belong to the biological systems we have already discussed, including those involved in cell survival, ionic homeostasis, neural plasticity, signal transduction and metabolism. Lastly, a study in 2012 conducted microarray analysis in lymphocytes from patients with MDD and subsyndromal symptomatic depression (SSD) [74]. In patients with MDD, they found 149 differentially expressed genes, enriched in 53 pathways, in comparison with control participants. Pathway analyses identified significant differences for IL-2 and IL-6-mediated signaling as well as TNF receptor signaling pathways. In patients with SSD, they identified 1,456 genes and 47 pathways that were significantly different when compared with controls, with 20 genes overlapping with those found in patients with MDD. Pathways found to be differentially expressed in patients with SSD included cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions and G protein signaling. Only two pathways were found to be involved in both MDD and SSD: the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway and the Wnt signaling pathway, both of which have been previously implicated in mood disorders [75, 76].

Although strictly speaking not a transcriptomics study in patients with depression, it is worth mentioning our recent study in the human hippocampal cells model [77]. In this study, we mimicked depression 'in a dish' by incubating cells with stress-level concentrations of the main human glucocorticoid hormone, cortisol. Transcriptomics analyses have identified inhibition of the 'Hedgehog pathway' as a candidate mechanism by which depression can reduce neurogenesis. It is of interest that, in the same study, we also found that Hedgehog-signaling is inhibited in the hippocampus of adult prenatally stressed rats with high glucocorticoid levels, again confirming the ability of gene expression approach to identify findings that are replicated consistently across different experimental models.

Conclusions

We have presented data on peripheral mRNA gene expression in patients with depression across MDD and BPD, obtained from whole blood, isolated mononuclear cells and isolated monocytes. All studies identified a pattern of altered expression in several genes belonging to three biological systems of interest: inflammation, GR functionality and neuroplasticity. Of note is the frequent pattern of state-related gene expression changes that are normalized either by remission or by antidepressant treatment. The association between gene expression and treatment response identifies this biomarker approach as particularly relevant from a clinical point of view. However, the temporal relationship of these gene expression changes with other factors, such as exposure to stress, is still unclear. This is relevant especially considering the frequent occurrence of stressors in these clinical groups. For example, a study on socioeconomic circumstances used transcriptome gene expression measurements followed by bioinformatics analysis of genes whose expression is regulated by specific transcription factors, including the GR and NF-κB. The authors described an upregulation of target genes for NF-κB and a downregulation of target genes for GR, consistent with a pattern of glucocorticoid resistance and increased inflammation, that is, a pattern similar to that described in depression [78]. We also do not know whether some of these changes in gene expression represent the marker of a genetic predisposition to encounter psychopathology; for example, we have previously shown that genetic variants in CNS and immune genes increase the association between depression and inflammation [79].

It should also be noted that the many pathways involved in the onset of depressive symptoms are of course interrelated and dynamic in nature. Because of this complexity, it has been proposed that a systems biology approach, combining information from gene expression analysis, protein data and well-validated animal models, is necessary to untangle the exact relevant pathways as well as novel molecular mechanisms [80]. Despite these unanswered questions, peripheral blood gene expression is a strong and clinically relevant system to identify biomarkers related to pathology and treatment response, and also to discover unknown mechanisms underlying the development of mood disorders. The identification of both could help in the personalization of therapy and in the future development of novel treatments.

Abbreviations

- Adcy5:

-

adenylate cyclise 5

- ApoE:

-

apolipoprotein E

- ARTN:

-

artemin

- BAG1:

-

BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 1

- BDNF:

-

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BPD:

-

bipolar disorder

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- COX-2:

-

cyclooxygenase-2

- CRH:

-

corticotropin-releasing hormone

- DAP12:

-

DNAX-activation protein of 12 kDa

- EMP1:

-

epithelial membrane protein 1

- FKBP:

-

FK506 binding protein

- GDNF:

-

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- Glo1:

-

glyoxalase-1

- GR:

-

glucocorticoid receptor

- HPA:

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- ICAM:

-

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IFN-γ:

-

interferon gamma

- IL:

-

interleukin

- MDD:

-

major depressive disorder

- MIF:

-

macrophage inhibiting factor

- MPO:

-

myeloperoxidase

- NCAM:

-

neural cell adhesion molecule

- NCOA1:

-

nuclear receptor coactivator 1

- NF-κB:

-

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NT-3:

-

neurotrophin-3

- PCNT2:

-

pericentrin 2

- PLA2G2A:

-

phospholipase A2

- PPID:

-

peptidylprolyl isomerase D

- PU.1:

-

purine-rich Box-1

- REST:

-

repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor

- SSD:

-

subsyndromal symptomatic depression

- TNF-α:

-

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TNFsf12-13:

-

tumor necrosis factor superfamily member 12-13

- TREM-1:

-

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1

- VCAM-1:

-

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR2:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2.

References

Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctot KL: A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 67: 446-457. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033.

Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J: Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009, 71: 171-186. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b.

Pariante CM, Lightman SL: The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31: 464-468. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006.

Pittenger C, Duman RS: Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008, 33: 88-109. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574.

Maes M, Galecki P, Chang YS, Berk M: A review on the oxidative and nitrosative stress (O&NS) pathways in major depression and their possible contribution to the (neuro)degenerative processes in that illness. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 35: 676-692. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.004.

Moylan S, Maes M, Wray NR, Berk M: The neuroprogressive nature of major depressive disorder: pathways to disease evolution and resistance, and therapeutic implications. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, [Epub ahead of print]

Sunde RA: mRNA transcripts as molecular biomarkers in medicine and nutrition. J Nutr Biochem. 2010, 21: 665-670. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.11.012.

Liew CC, Ma J, Tang HC, Zheng R, Dempsey AA: The peripheral blood transcriptome dynamically reflects system wide biology: a potential diagnostic tool. J Lab Clin Med. 2006, 147: 126-132. 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.005.

Sullivan PF, Fan C, Perou CM: Evaluating the comparability of gene expression in blood and brain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006, 141B: 261-268. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30272.

Danese A, Moffitt TE, Pariante CM, Ambler A, Poulton R, Caspi A: Elevated inflammation levels in depressed adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. ArchGenPsychiatry. 2008, 65: 409-415.

Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB: The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008, 33: 693-710. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008.

Mazure CM, Bruce ML, Maciejewski PK, Jacobs SC: Adverse life events and cognitive-personality characteristics in the prediction of major depression and antidepressant response. Am J Psychiatry. 2000, 157: 896-903. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.896.

Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Carvalho LA, Pariante CM: Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011, 35: 722-729. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011.

Zunszain PA, Hepgul N, Pariante CM: Inflammation and depression. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012, [Epub ahead of print]

Smith RS: The macrophage theory of depression. Med Hypotheses. 1991, 35: 298-306. 10.1016/0306-9877(91)90272-Z.

Maes M: Evidence for an immune response in major depression: a review and hypothesis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1995, 19: 11-38. 10.1016/0278-5846(94)00101-M.

Maes M, Bosmans E, Suy E, Vandervorst C, De Jonckheere C, Raus J: Immune disturbances during major depression: upregulated expression of interleukin-2 receptors. Neuropsychobiology. 1990, 24: 115-120. 10.1159/000119472.

Wise MG, Taylor SE: Anxiety and mood disorders in medically ill patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990, 51 (Suppl): 27-32.

Pollak Y, Yirmiya R: Cytokine-induced changes in mood and behaviour: implications for 'depression due to a general medical condition', immunotherapy and antidepressive treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 5: 389-399. 10.1017/S1461145702003152.

Maes M: Cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1994, 36: 498-499.

Shelton RC, Claiborne J, Sidoryk-Wegrzynowicz M, Reddy R, Aschner M, Lewis DA, Mirnics K: Altered expression of genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis in frontal cortex in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16: 751-762. 10.1038/mp.2010.52.

Tsao CW, Lin YS, Chen CC, Bai CH, Wu SR: Cytokines and serotonin transporter in patients with major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 30: 899-905. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.029.

Cattaneo A, Gennarelli M, Uher R, Breen G, Farmer A, Aitchison KJ, Craig IW, Anacker C, Zunsztain PA, McGuffin P, Pariante CM: Candidate genes expression profile associated with antidepressants response in the GENDEP study: differentiating between baseline 'predictors' and longitudinal 'targets'. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013, 38 (2): 376-10.1038/npp.2012.211.

Zhang HL, Wu J, Zhu J: The role of apolipoprotein E in Guillain-Barre syndrome and experimental autoimmune neuritis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010, 2010: 357412.

Suzuki K, Iwata Y, Matsuzaki H, Anitha A, Suda S, Iwata K, Shinmura C, Kameno Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Nakamura K, Takei N, Mori N: Reduced expression of apolipoprotein E receptor type 2 in peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 34: 1007-1010. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.014.

Herz J, Chen Y: Reelin, lipoprotein receptors and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006, 7: 850-859. 10.1038/nrn2009.

Fatemi SH, Kroll JL, Stary JM: Altered levels of reelin and its isoforms in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Neuroreport. 2001, 12: 3209-3215. 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00014.

Su KP, Huang SY, Peng CY, Lai HC, Huang CL, Chen YC, Aitchison KJ, Pariante CM: Phospholipase A2 and cyclooxygenase 2 genes influence the risk of interferon-alpha-induced depression by regulating polyunsaturated fatty acids levels. Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 67: 550-557. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.005.

Galecki P, Maes M, Florkowski A, Lewinski A, Galecka E, Bienkiewicz M, Szemraj J: An inducible nitric oxide synthase polymorphism is associated with the risk of recurrent depressive disorder. Neurosci Lett. 2010, 486: 184-187. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.048.

Vaccarino V, Brennan ML, Miller AH, Bremner JD, Ritchie JC, Linclau F, Veleclar E, Su SY, Murrah NV, Jones L, Jawed F, Dai J, Goldberg J, Hazen SL: Association of major depressive disorder with serum myeloperoxidase and other markers of inflammation: a twin study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 64: 476-483. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.023.

Herken H, Gurel A, Selek S, Armutcu F, Ozen ME, Bulut M, Kap O, Yumru M, Savas HA, Akyol O: Adenosine deaminase, nitric oxide, superoxide dismutase, and xanthine oxidase in patients with major depression: impact of antidepressant treatment. Arch Med Res. 2007, 38: 247-252. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.10.005.

Galecki P, Galecka E, Maes M, Chamielec M, Orzechowska A, Bobinska K, Lewinski A, Szemraj J: The expression of genes encoding for COX-2, MPO, iNOS, and sPLA2-IIA in patients with recurrent depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2012, 138: 360-366. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.016.

Weigelt K, Carvalho LA, Drexhage RC, Wijkhuijs A, de Wit H, van Beveren NJ, Birkenhager TK, Bergink V, Drexhage HA: TREM-1 and DAP12 expression in monocytes of patients with severe psychiatric disorders. EGR3, ATF3 and PU.1 as important transcription factors. Brain Behav Immun. 2011, 25: 1162-1169. 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.006.

Pariante CM, Miller AH: Glucocorticoid receptors in major depression: relevance to pathophysiology and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2001, 49: 391-404. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01088-X.

Katz ER, Stowe ZN, Newport DJ, Kelley ME, Pace TW, Cubells JF, Binder EB: Regulation of mRNA expression encoding chaperone and co-chaperone proteins of the glucocorticoid receptor in peripheral blood: association with depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Psychol Med. 2012, 42: 943-956. 10.1017/S0033291711002121.

Matsubara T, Funato H, Kobayashi A, Nobumoto M, Watanabe Y: Reduced glucocorticoid receptor alpha expression in mood disorder patients and first-degree relatives. Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 59: 689-695. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.026.

Fujimoto M, Uchida S, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Otsuki K, Matsubara T, Suetsugi M, Funato H, Watanabe Y: Reduced expression of glyoxalase-1 mRNA in mood disorder patients. Neurosci Lett. 2008, 438: 196-199. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.024.

Ranganathan S, Ciaccio PJ, Walsh ES, Tew KD: Genomic sequence of human glyoxalase-I: analysis of promoter activity and its regulation. Gene. 1999, 240: 149-155. 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00420-5.

Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Cleare AJ, Checkley SA, English J, Kerwin RW, Lightman S: Four days of citalopram increase suppression of cortisol secretion by prednisolone in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004, 177: 200-206. 10.1007/s00213-004-1925-4.

Pariante CM, Alhaj HA, Arulnathan VE, Gallagher P, Hanson A, Massey E, McAllister-Williams RH: Central glucocorticoid receptor-mediated effects of the antidepressant, citalopram, in humans: a study using EEG and cognitive testing. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012, 37: 618-628. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.08.011.

Juruena MF, Pariante CM, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Lightman S, Cleare AJ: Prednisolone suppression test in depression: prospective study of the role of HPA axis dysfunction in treatment resistance. Br J Psychiatry. 2009, 194: 342-349. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.050278.

Juruena MF, Cleare AJ, Papadopoulos AS, Poon L, Lightman S, Pariante CM: The prednisolone suppression test in depression: dose-response and changes with antidepressant treatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010, 35: 1486-1491. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.04.016.

Anacker C, Zunszain PA, Cattaneo A, Carvalho LA, Garabedian MJ, Thuret S, Price J, Pariante CM: Antidepressants increase human hippocampal neurogenesis by activating the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Psychiatry. 2011, 16: 738-750. 10.1038/mp.2011.26.

Pariante CM, Hye A, Williamson R, Makoff A, Lovestone S, Kerwin RW: The antidepressant clomipramine regulates cortisol intracellular concentrations and glucocorticoid receptor expression in fibroblasts and rat primary neurones. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003, 28: 1553-1561. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300195.

Pandey GN, Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Ren X, Zhang H, Pavuluri MN: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene and protein expression in pediatric and adult depressed subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010, 34: 645-651. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.003.

Cattaneo A, Bocchio-Chiavetto L, Zanardini R, Milanesi E, Placentino A, Gennarelli M: Reduced peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA levels are normalized by antidepressant treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 13: 103-108. 10.1017/S1461145709990812.

Alder J, Thakker-Varia S, Bangasser DA, Kuroiwa M, Plummer MR, Shors TJ, Black IB: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced gene expression reveals novel actions of VGF in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2003, 23: 10800-10808.

Cattaneo A, Sesta A, Calabrese F, Nielsen G, Riva MA, Gennarelli M: The expression of VGF is reduced in leukocytes of depressed patients and it is restored by effective antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35: 1423-1428. 10.1038/npp.2010.11.

Otsuki K, Uchida S, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Fujimoto M, Matsubara T, Funato H, Watanabe Y: Altered expression of neurotrophic factors in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2008, 42: 1145-1153. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.010.

Smith MA, Makino S, Kvetnansky R, Post RM: Stress and glucocorticoids affect the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 mRNAs in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1995, 15: 1768-1777.

Dwivedi Y, Mondal AC, Rizavi HS, Conley RR: Suicide brain is associated with decreased expression of neurotrophins. Biol Psychiatry. 2005, 58: 315-324. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.014.

Gerke V, Weber K: The regulatory chain in the p36-kd substrate complex of viral tyrosine-specific protein kinases is related in sequence to the S-100 protein of glial cells. EMBO J. 1985, 4: 2917-2920.

Svenningsson P, Chergui K, Rachleff I, Flajolet M, Zhang X, El Yacoubi M, Vaugeois JM, Nomikos GG, Greengard P: Alterations in 5-HT1B receptor function by p11 in depression-like states. Science. 2006, 311: 77-80. 10.1126/science.1117571.

Su TP, Zhang L, Chung MY, Chen YS, Bi YM, Chou YH, Barker JL, Barrett JE, Maric D, Li XX, Li H, Webster MJ, Benedek D, Carlton JR, Ursano R: Levels of the potential biomarker p11 in peripheral blood cells distinguish patients with PTSD from those with other major psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2009, 43: 1078-1085. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.010.

Zhang L, Su TP, Choi K, Maree W, Li CT, Chung MY, Chen YS, Bai YM, Chou YH, Barker JL, Barrett JE, Li XX, Li H, Benedek DM, Ursano R: P11 (S100A10) as a potential biomarker of psychiatric patients at risk of suicide. J Psychiatr Res. 2011, 45: 435-441. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.08.012.

Panutsopulos D, Zafiropoulos A, Krambovitis E, Kochiadakis GE, Igoumenidis NE, Spandidos DA: Peripheral monocytes from diabetic patients with coronary artery disease display increased bFGF and VEGF mRNA expression. J Transl Med. 2003, 1: 6-10.1186/1479-5876-1-6.

Iga J, Ueno S, Yamauchi K, Numata S, Tayoshi-Shibuya S, Kinouchi S, Nakataki M, Song H, Hokoishi K, Tanabe H, Sano A, Ohmori T: Gene expression and association analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor in major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 31: 658-663. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.12.011.

Dome P, Teleki Z, Rihmer Z, Peter L, Dobos J, Kenessey I, Tovari J, Timar J, Paku S, Kovacs G, Dome B: Circulating endothelial progenitor cells and depression: a possible novel link between heart and soul. Mol Psychiatry. 2009, 14: 523-531. 10.1038/sj.mp.4002138.

Anitha A, Nakamura K, Yamada K, Iwayama Y, Toyota T, Takei N, Iwata Y, Suzuki K, Sekine Y, Matsuzaki H, Kawai M, Miyoshi K, Katayama T, Matsuzaki S, Baba K, Honda A, Hattori T, Shimizu S, Kumamoto N, Tohyama M, Yoshikawa T, Mori N: Gene and expression analyses reveal enhanced expression of pericentrin 2 (PCNT2) in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 63: 678-685. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.010.

Nakataki M, Iga J, Numata S, Yoshimoto E, Kodera K, Watanabe SY, Song H, Ueno S, Ohmori T: Gene expression and association analysis of the epithelial membrane protein 1 gene in major depressive disorder in the Japanese population. Neurosci Lett. 2011, 489: 126-130. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.12.001.

Sandi C: Stress, cognitive impairment and cell adhesion molecules. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004, 5: 917-930. 10.1038/nrn1555.

Vawter MP, Hemperly JJ, Hyde TM, Bachus SE, VanderPutten DM, Howard AL, Cannon-Spoor HE, McCoy MT, Webster MJ, Kleinman JE, Freed WJ: VASE-containing N-CAM isoforms are increased in the hippocampus in bipolar disorder but not schizophrenia. Exp Neurol. 1998, 154: 1-11. 10.1006/exnr.1998.6889.

Poltorak M, Frye MA, Wright R, Hemperly JJ, George MS, Pazzaglia PJ, Jerrels SA, Post RM, Freed WJ: Increased neural cell adhesion molecule in the CSF of patients with mood disorder. J Neurochem. 1996, 66: 1532-1538.

Wakabayashi Y, Uchida S, Funato H, Matsubara T, Watanuki T, Otsuki K, Fujimoto M, Nishida A, Watanabe Y: State-dependent changes in the expression levels of NCAM-140 and L1 in the peripheral blood cells of bipolar disorders, but not in the major depressive disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008, 32: 1199-1205. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.03.005.

Schoenherr CJ, Anderson DJ: The neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF): a coordinate repressor of multiple neuron-specific genes. Science. 1995, 267: 1360-1363. 10.1126/science.7871435.

Somekawa S, Imagawa K, Naya N, Takemoto Y, Onoue K, Okayama S, Takeda Y, Kawata H, Horii M, Nakajima T, Uemura S, Mochizuki N, Saito Y: Regulation of aldosterone and cortisol production by the transcriptional repressor neuron restrictive silencer factor. Endocrinology. 2009, 150: 3110-3117. 10.1210/en.2008-1624.

Westbrook TF, Hu G, Ang XL, Mulligan P, Pavlova NN, Liang A, Leng Y, Maehr R, Shi Y, Harper JW, Elledge SJ: SCFbeta-TRCP controls oncogenic transformation and neural differentiation through REST degradation. Nature. 2008, 452: 370-374. 10.1038/nature06780.

Otsuki K, Uchida S, Wakabayashi Y, Matsubara T, Hobara T, Funato H, Watanabe Y: Aberrant REST-mediated transcriptional regulation in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010, 44: 378-384. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.009.

Beech RD, Lowthert L, Leffert JJ, Mason PN, Taylor MM, Umlauf S, Lin A, Lee JY, Maloney K, Muralidharan A, Lorberg B, Zhao H, Newton SS, Mane S, Epperson CN, Sinha R, Blumberg H, Bhagwagar Z: Increased peripheral blood expression of electron transport chain genes in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2010, 12: 813-824. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00882.x.

Pace TW, Mletzko TC, Alagbe O, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Miller AH, Heim CM: Increased stress-induced inflammatory responses in male patients with major depression and increased early life stress. Am J Psychiatry. 2006, 163: 1630-1633. 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1630.

Segman RH, Goltser-Dubner T, Weiner I, Canetti L, Galili-Weisstub E, Milwidsky A, Pablov V, Friedman N, Hochner-Celnikier D: Blood mononuclear cell gene expression signature of postpartum depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2010, 15: 93-100. 10.1038/mp.2009.65. 102

Anacker C, Pariante CM: Can adult neurogenesis buffer stress responses and depressive behaviour?. Mol Psychiatry. 2012, 17: 9-10. 10.1038/mp.2011.133.

Kalman J, Palotas A, Juhasz A, Rimanoczy A, Hugyecz M, Kovacs Z, Galsi G, Szabo Z, Pakaski M, Feher LZ, Janka Z, Puskas LG: Impact of venlafaxine on gene expression profile in lymphocytes of the elderly with major depression--evolution of antidepressants and the role of the 'neuro-immune' system. Neurochem Res. 2005, 30: 1429-1438. 10.1007/s11064-005-8513-9.

Yi Z, Li Z, Yu S, Yuan C, Hong W, Wang Z, Cui J, Shi T, Fang Y: Blood-based gene expression profiles models for classification of subsyndromal symptomatic depression and major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e31283-10.1371/journal.pone.0031283.

Duman CH, Schlesinger L, Kodama M, Russell DS, Duman RS: A role for MAP kinase signaling in behavioral models of depression and antidepressant treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 61: 661-670. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.047.

Voleti B, Duman RS: The roles of neurotrophic factor and Wnt signaling in depression. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012, 91: 333-338. 10.1038/clpt.2011.296.

Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Luoni A, Musaelyan K, Zunszain PA, Milanesi E, Rybka J, Berry A, Cirulli F, Thuret S, Price J, Riva MA, Gennarelli M, Pariante CM: Glucocorticoid-Related Molecular Signaling Pathways Regulating Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013.

Miller GE, Chen E, Fok AK, Walker H, Lim A, Nicholls EF, Cole S, Kobor MS: Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 14716-14721. 10.1073/pnas.0902971106.

Bull SJ, Huezo-Diaz P, Binder EB, Cubells JF, Ranjith G, Maddock C, Miyazaki C, Alexander N, Hotopf M, Cleare AJ, Norris S, Cassidy E, Aitchison KJ, Miller AH, Pariante CM: Functional polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 and serotonin transporter genes, and depression and fatigue induced by interferon-alpha and ribavirin treatment. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009, 14: 1095-1104. 10.1038/mp.2008.48.

Leonard B, Maes M: Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012, 36: 764-785. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.005.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1741-7015/11/28/prepub

Acknowledgements

NH, PAZ and CMP are supported by a grant from the Commission of European Communities Seventh Framework Programme (Collaborative Project Grant Agreement no. 22963, Mood Inflame); by the National Institute for Health Research Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre in Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London; and by the grant from the Medical Research Council (UK) MR/J002739/1. PAZ is also supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. AC and CMP are also supported by a grant from the Psychiatry Research Trust, UK (McGregor 97).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

CMP in the last 3 years has received fees as a speaker or as a member of advisory boards, as well as research funding, from pharmaceutical companies that commercialize or are developing antidepressants, such as Lilly, Servier and Janssen. PAZ received fees as a speaker from Servier. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors' contributions

NH and CMP conceptualized this work, conducted the literature search and drafted the initial manuscript. AC and PAZ significantly contributed to the subsequent revisions, and gave approval to submit the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hepgul, N., Cattaneo, A., Zunszain, P.A. et al. Depression pathogenesis and treatment: what can we learn from blood mRNA expression?. BMC Med 11, 28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-28