Abstract

Background

The bacterial ribosome is a primary target of several classes of antibiotics. Investigation of the structure of the ribosomal subunits in complex with different antibiotics can reveal the mode of inhibition of ribosomal protein synthesis. Analysis of the interactions between antibiotics and the ribosome permits investigation of the specific effect of modifications leading to antimicrobial resistances.

Streptogramins are unique among the ribosome-targeting antibiotics because they consist of two components, streptogramins A and B, which act synergistically. Each compound alone exhibits a weak bacteriostatic activity, whereas the combination can act bactericidal. The streptogramins A display a prolonged activity that even persists after removal of the drug. However, the mode of activity of the streptogramins has not yet been fully elucidated, despite a plethora of biochemical and structural data.

Results

The investigation of the crystal structure of the 50S ribosomal subunit from Deinococcus radiodurans in complex with the clinically relevant streptogramins quinupristin and dalfopristin reveals their unique inhibitory mechanism. Quinupristin, a streptogramin B compound, binds in the ribosomal exit tunnel in a similar manner and position as the macrolides, suggesting a similar inhibitory mechanism, namely blockage of the ribosomal tunnel. Dalfopristin, the corresponding streptogramin A compound, binds close to quinupristin directly within the peptidyl transferase centre affecting both A- and P-site occupation by tRNA molecules.

Conclusions

The crystal structure indicates that the synergistic effect derives from direct interaction between both compounds and shared contacts with a single nucleotide, A2062. Upon binding of the streptogramins, the peptidyl transferase centre undergoes a significant conformational transition, which leads to a stable, non-productive orientation of the universally conserved U2585. Mutations of this rRNA base are known to yield dominant lethal phenotypes. It seems, therefore, plausible to conclude that the conformational change within the peptidyl transferase centre is mainly responsible for the bactericidal activity of the streptogramins and the post-antibiotic inhibition of protein synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Structural studies of complexes of both small and large ribosomal subunits with several clinically important antibiotics, for example, macrolides, lincosamides or chloramphenicol [1–3], have significantly advanced our understanding of the inhibitory action of these antimicrobial agents. However, the mechanism of the streptogramin class of antibiotics remains to be fully elucidated [4].

Streptogramins, which are produced by the genus Streptomyces, are divided into two types, A and B, both composed of macrocyclic lactone rings. Type B streptogramins (SB) are cyclic hexadepsipeptides whereas type A (SA) are highly modified cyclopeptides with multiple conjugated double bonds (Figure 1A). The antimicrobial activity of streptogramins has been well characterized (reviewed in [5]), revealing a unique, cooperative action. Alone, each compound exhibits a moderate bacteriostatic activity, but in combination the synergistic interplay between the compounds can produce a bactericidal effect [6, 7].

Interactions of streptogramins with 23S rRNA. (A) Chemical structure of quinupristin and dalfopristin. The hydrogen bonds towards 23S rRNA nucleotides are indicated. (B) Overview of the nucleotides involved in binding in comparison with those indicated by various biochemical and genetic experiments [5, 7, 12-30]. Both images contain numbering for E. coli (in green) and for D. radiodurans (in red). The sequence itself corresponds to 23S rRNA of D. radiodurans. All other images use numbering according to E. coli.

Type B streptogramins act on the 50S ribosomal subunit in a similar fashion as the macrolides and compete for the same binding site. The SB do not affect the peptidyl transferase reaction, but inhibit elongation after a few cycles of peptide bond formation; by analogy with the macrolides, SB are presumed to bind within the tunnel and block the path of the nascent polypeptide chain. Consistently, resistance to both classes of antibiotics arise through common mechanisms, for example, the resistance against macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins B (MLSB) results from methylation or mutation of A2058.

In contrast, SA act to prevent protein biosynthesis by blocking peptide bond formation. Type A streptogramins apparently do this by interfering with substrate binding at both acceptor and donor sites of the peptidyl transferase centre (PTC) [8], thereby inhibiting the peptidyl transferase reaction directly. Suppression of cell growth persists for a prolonged lag after removal of the drug [9, 10], presumably due to a stable perturbation of the conformation of the PTC induced by the binding of SA [11, 12].

The most recently approved streptogramin formulation is Synercid®, a 30:70 combination of dalfopristin (SA) and quinupristin (SB). The greatly enhanced solubility and bioavailability of Synercid®, and its excellent activity against Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative bacteria, has renewed interest in the medical use of the streptogramins.

To elucidate the unique cooperative effect of the streptogramin antibiotics, we investigated the structure of the 50S ribosomal subunit from Deinococcus radiodurans (D50S) in complex with both dalfopristin and quinupristin. The 3.4 Å crystal structure allows the unambiguous localization of dalfopristin and quinupristin in the core region of the 50S ribosomal subunit, and enables for the first time a molecular understanding of the synergistic and prolonged inhibitory action of this clinically important class of antibiotics.

Results

Localization and interactions of quinupristin

Quinupristin is bound to 23S rRNA through an extensive network of hydrophobic interactions involving nucleotides of domain II, IV and V, hydrogen bonds between A2062 and C2586 (nucleotides are numbered according to the E. coli 23S rRNA sequence throughout the text), and the macrocyclic ring (Figure 1A, 2), in excellent agreement with biochemical and mutational data [5, 7, 12–30] (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the quinuclidinylthio-moiety (Figure 1A) occupies vacant space within the 50S subunit, suggesting that the addition of this moiety to the pristinamycin IA core enhances the bioavailability, but apparently not the binding properties, of quinupristin.

Structure of dalfopristin and quinupristin within the PTC. To facilitate visualization of the interactions of dalfopristin and quinupristin with 23S rRNA, rRNA bases not involved in binding have been omitted. (A) Local environment of dalfopristin (in orange). A2062 is highlighted in purple; nucleotides, which are interacting through hydrogen bonds with either dalfopristin or quinupristin, are shown in dark blue. (B) Local environment of quinupristin (in green). Colours are as in (A). (C) Stereo view of the electron density map of quinupristin (in green) and dalfopristin (in orange). Both compounds have been omitted during calculation of the sigmaA weighted difference map, which is contoured at 1.5σ. (D) Stereo representation of dalfopristin and quinupristin and their local environment. Colours as in (A).

The binding site of quinupristin is located at the entrance to the ribosomal tunnel, and does not contact the active site of the 50S subunit (Figure 3A,3B). This is in agreement with the observation that SB does not affect peptide bond formation directly, but permits the ribosome to form a few peptide bonds until further extension of the nascent chain is prevented by blockage caused by binding of SB. Quinupristin occupies the same space as the macrolides (Figure 3A), consistent with the strong competition observed between erythromycin and virginiamycin S (SB) [25]. In fact, erythromycin can completely abolish SB binding to the ribosome, illustrating the lower affinity of the SB. Remarkably, in the Haloarcula marismortui 50S (H50S)-streptogramin complex no significant binding of SB has been observed [4]. However, mutations of C2610U and especially A2058G, both of which are present in H. marismortui, have been found to confer resistance to SB by reducing the binding affinity of the drug [31]; therefore, they provide a plausible explanation for the absence of SB from the H50S complex.

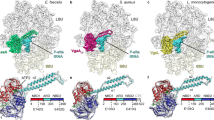

Comparison of antibiotic binding sites. (A) To visualize the relative orientations of different classes of antibiotics and substrates compared with dalfopristin and quinupristin, several structures have been aligned and overlaid: clindamycin (PDB entry 1JZX), erythromycin (1JZY), chloramphenicol (1K01) and CC-Puromycin molecules in A- (A-CCPuro) and P-site (P-CCPuro). CC-Puromycin coordinates were taken from Bashan et al. (2003) [40]. (B) Overview of the binding sites of quinupristin and dalfopristin within the 50S ribosomal subunit, in relation to the P-site tRNA and the ribosomal exit tunnel (highlighted in gold).

Localization and interactions of dalfopristin

Dalfopristin is located in a tight pocket within the PTC, bound by a network of hydrophobic interactions involving the whole macrocyclic ring as well as the ethanethiol moiety (Figure 1, 2, 3B). The macrocyclic ring forms hydrogen bonds with G2505 and G2061, and the only hydroxyl contained in dalfopristin is hydrogen bonding to G2505. However, the most prevalent SA resistance mechanism is based on the acetylation of this hydroxyl by virginiamycin acetyltransferase (VatD) [32]. Modification of the drug would, according to our structure, disrupt the hydrogen bond with G2505, and prohibit binding of acetylated SA by steric hindrance. A large number of rRNA bases within the PTC have been shown to have altered reactivity in the presence of SA [19, 21], among them G2058, A2059, A2439, G2505, U2506 and U2585, all of which directly contribute to the binding of dalfopristin (Figure 1B), demonstrating the agreement between structural and biochemical data.

The position of dalfopristin, which largely overlaps with that of chloramphenicol (Figure 3A), allows a clear interpretation of the inhibitory activity. Dalfopristin interferes with positioning of A- and P-site substrates (Figure 3A), although the CCA-end of tRNA might be flexible enough to bind unproductively even in the presence of SA. But, once the P-site is occupied, binding of dalfopristin to the ribosome will be suppressed, thus explaining why ribosomes actively engaged in protein synthesis are not susceptible to SA (reviewed in [5]). The loss of flexibility of the CCA-end in the P-site concomitant with nascent chain extension [33] might enhance this effect, since the effectiveness of SA decreases as the number of amino acids attached to the P-site tRNA increases [30].

Discussion

Synergism

Synergistic binding of quinupristin and dalfopristin is presumably facilitated by strong hydrophobic interactions existing between both streptogramins, which lead to a significant reduction of their solvent accessible surface. Additionally, both compounds share contacts with a single nucleotide, A2062, through hydrophobic interactions as well as hydrogen bonds. Biochemical data implicate A2062 as undergoing conformational changes induced by streptogramin binding [16, 20]. When ribosomes were incubated with SA and SB, the base of A2062, which was protected by SB alone, became accessible to dimethyl sulphate, suggesting that the conformational alterations of A2062 were induced by SA [16].

This proposal is further supported by the crystal structure of H50S, which contains two alternating conformations of A2062 [4]. In the complex of H50S with virginiamycin M (SA), A2062 also appears to have undergone a conformational change, being rotated by ~90° compared with the prevalent orientation found in the native structure of H50S. But, as Hansen et al. (2003) [4] concluded, the conformational change of A2062 does not explain the post-antibiotic effect of SA, since tRNA or substrate analogues bound to 50S induce a similar conformational change. In the native structure of D50S [34], A2062 obtains an orientation similar to the one observed in the H50S streptogramin complex (Figure 4A), but is rotated by ~15° in the D50S streptogramin complex to prevent steric clashes with SB and enable simultaneous accommodation of both SA and SB. In this orientation, A2062 stacks between quinupristin and the macrocyclic ring of dalfopristin, such that any modification will severely affect the binding of both compounds. Mutations of A2062 are hence among the very few 23S rRNA modifications giving rise to both SA and SB resistance [28]. The movement also affects the local environment, such that A2058 and A2060 are slightly displaced compared with the native structure (Figure 4A), which might contribute to the suppression of MLSB resistance by the presence of SA [11].

Conformation of the PTC. (A) Different orientations of A2062 and its local environment for native D50S (purple), for the complex with Synercid® (blue) and for the H50S streptogramin complex (yellow). (B) Comparison of the position of dalfopristin in D50S (orange) with the position of virginiamycin M in H50S (light green), and the corresponding folds of 23S rRNA in the vicinity of U2585 (in blue for D50S and in yellow for H50S). (C) Structure and electron density around U2585. For comparison, the orientation of U2585 in the native D50S structure is also shown. The electron density is a sigmaA weighted difference map omitting the whole peptidyl-transferase ring from the calculation. (D) Local structure around U2585 overlaid with the native structure; putative hydrogen bonds of U2585 in its new orientation are indicated. (E) Approximate energy profile derived from modelling intermediate conformations, units being arbitrary. N indicates the energy of the native conformation and S the one of the complex with Synercid®.

The most remarkable conformational changes induced within the PTC upon binding of dalfopristin are the alterations in the vicinity of U2585 (Figure 4B,4C,4D). This nucleotide, which points towards the tunnel in the native structure, appears to be rotated by about 180° to point in the opposite direction when the streptogramins are bound. This enables U2585 to form hydrogen bonds with C2606 and G2588 (Figure 4D), which should lead to a fairly stable alteration of the PTC.

To gain insight into the stability of this specific rRNA conformation, we performed a simple simulation by modelling a number of intermediates connecting the native and the streptogramin induced conformation of the region around U2585. Assuming that the transition does not induce large-range perturbations of 23S rRNA, the tightness of the region allows a single trajectory, which requires only moderate movements of A2439 to permit the continuous rotation of U2585 by 180°. Calculating the energy of each intermediate conformation yields a qualitative picture of the energy profile, showing that the transition requires the passage through an energy barrier (Figure 4E), to and from the native and streptogramin bound structures, which have essentially the same energy state. Binding of dalfopristin is obviously sufficient to force the native conformation of U2585 through the energy barrier to the alternate conformation, and spontaneous reversal of this transition will be comparably slow. This is in agreement with the observation that recovery of ribosomal activity after removal of SA is followed by a prolonged lag [9, 10], suggesting that the post-antibiotic effect of SA can be attributed exclusively to the conformational change in U2585. Preliminary data of a complex of D50S with the SA mikamycin A alone showed the same reorientation of U2585 (data not shown), which confirms that the conformational change is neither unique for dalfopristin nor dependent on the presence of SB.

Although inversion of the orientation of U2585 appears to be most crucial for the activity of SA, the structure of the H50S-streptogramin complex [4] shows no significant conformational change in U2585. This correlates with the peculiar differences observed in the footprinting pattern of streptogramins on eubacterial and archaeal ribosomes [21], and suggests that these antibiotics might exert a different inhibitory mechanism between archea and eubacteria.

Implications on peptide bond formation

The universally conserved nucleotide U2585 has been implicated in the positioning of P-site substrates by various biochemical experiments, and mutations of U2585 have been shown to yield a lethal phenotype [35–39]. The recent structures of A- and P-site substrates in complex with D50S [40] or H50S [41] placed U2585 in the direct vicinity of the 3' adenosine of the substrates and its attached amino acid (or mimics thereof). The proposed mechanism for peptide bond formation, based on the local two-fold symmetry inside the PTC, also suggests a direct interaction of the terminal adenosine of P-site tRNA with U2585 and assigns a pivotal role for the rotary motion during peptide bond formation to this nucleotide [42]. The correct conformation of U2585 is hence essential for proper positioning of the substrate in the P-site [35–39], which is a prerequisite for the formation of a functional 70S initiation complex. The streptogramin induced conformation of U2585 should, therefore, severely affect the proper positioning of the 3' end of the P-site-bound tRNA, in agreement with biochemical data [16]. Conversely, interactions between U2585 and the P-site substrate might well stabilize the native conformation and hence suppress the conformational change required for SA binding, contributing to the poor inhibition by SA of ribosomes engaged in protein synthesis.

Conclusions

The structural studies of the 50S ribosomal subunit from Deinococcus radiodurans in complex with the streptogramins dalfopristin and quinupristin provides a first glance at the synergistic inhibition of protein synthesis. The bactericidal activity of the streptogramins can at least partially be attributed to the induction of the conformational change of the universally conserved nucleotide U2585. The altered conformation of U2585 has been shown to be stabilized by hydrogen bonds, leading to a rather stable distortion of the PTC. Therefore, it is likely that the conformational change is also responsible for the prolonged activity of SA, which can persist for an extended period after removal of the drug. The synergistic inhibition appears to be a direct consequence of interactions between the two streptogramin components, but the fixation of A2062 in an orientation permitting simultaneous binding of both compounds contributes significantly to the synergistic activity.

Methods

Base and amino acid numbering

Nucleotides named (ACGU)1234 are numbered according to the 23S rRNA sequence from E. coli to permit a direct comparison with biochemical data. Translation tables converting D. radiodurans to E. coli to H. marismortui are available from the authors or at http://www.riboworld.com/nuctrans/. 23S rRNA sequence alignments were based on the 2D-structure diagrams obtained from Cannone et al. (2002) [43].

Crystallization

Crystals of the 50S ribosomal subunit were obtained as previously described by Harms et al. (2001) [34]. Co-crystallization was carried out in the presence of four-fold excesses of dalfopristin and a 10-fold excess of quinupristin.

X-ray diffraction

Data were collected at 85 K from shock-frozen crystals with synchrotron radiation beam at ID19 at Argonne Photon Source/Argonne National Laboratory (APS/ANL) and ID14/2, ID14/4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility/European Molecular Biology Laboratory (ESRF/EMBL). Data were recorded on ADSC-Quantum 4 or APS-CCD detectors and processed with HKL2000 [44] and the CCP4 suite [45]. See Table 1 for data statistics.

Localization and refinement

The native structure of the 50S subunit was refined against the structure factor amplitudes of the 50S antibiotic complexes, using rigid body refinement as implemented in CNS [46]. For the calculation of the free R-factor, 5% of the data were omitted during refinement. The positions of the antibiotics were readily determined from sigmaA weighted difference maps (Figure 2C). The quality of the difference maps revealed unambiguously the position and orientation of the ligands. Since no structural model of quinupristin was available, virginiamycin S was used as an initial model; the quinuclidinylthio-moiety was added manually and subsequently minimized. The agreement between the initial model and the density was sufficient to assume that the conformation of the macrocyclic ring of quinupristin and virginiamycin S were identical. The placement of the quinuclidinylthio-moiety is unambiguous; however, the density for this moiety is considerably weaker (invisible contouring higher than 2.0σ) than the density of the core of the quinupristin structure (still visible beyond 3.5σ) (Figure 2C). Further refinement was carried out using CNS [46]. See Table 1 for refinement statistics.

Coordinates and figures

Three-dimensional figures were produced with Ribbons [47]. The ribosome-ligand interactions were originally determined with LIGPLOT [48], but for sake of clarity represented in a sketched manner. Final coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank [49] under accession number 1SM1.

References

Schlunzen F, Zarivach R, Harms J, Bashan A, Tocilj A, Albrecht R, Yonath A, Franceschi F: Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature. 2001, 413: 814-821. 10.1038/35101544.

Hansen JL, Ippolito JA, Ban N, Nissen P, Moore PB, Steitz TA: The structures of four macrolide antibiotics bound to the large ribosomal subunit. Mol Cell. 2002, 10: 117-128. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00570-1.

Schlunzen F, Harms JM, Franceschi F, Hansen HA, Bartels H, Zarivach R, Yonath A: Structural basis for the antibiotic activity of ketolides and azalides. Structure (Camb). 2003, 11: 329-338. 10.1016/S0969-2126(03)00022-4.

Hansen JL, Moore PB, Steitz TA: Structures of Five Antibiotics Bound at the Peptidyl Transferase Center of the Large Ribosomal Subunit. J Mol Biol. 2003, 330: 1061-1075. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00668-5.

Cocito C, Di Giambattista M, Nyssen E, Vannuffel P: Inhibition of protein synthesis by streptogramins and related antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997, 39 Suppl A: 7-13. 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.7.

Allignet J, Aubert S, Morvan A, el Solh N: Distribution of genes encoding resistance to streptogramin A and related compounds among staphylococci resistant to these antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996, 40: 2523-2528.

Malbruny B, Canu A, Bozdogan B, Fantin B, Zarrouk V, Dutka-Malen S, Feger C, Leclercq R: Resistance to quinupristin-dalfopristin due to mutation of L22 ribosomal protein in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 2200-2207. 10.1128/AAC.46.7.2200-2207.2002.

Chinali G, Moureau P, Cocito CG: The action of virginiamycin M on the acceptor, donor, and catalytic sites of peptidyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1984, 259: 9563-9568.

Nyssen E, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C: Analysis of the reversible binding of virginiamycin M to ribosome and particle functions after removal of the antibiotic. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989, 1009: 39-46. 10.1016/0167-4781(89)90076-6.

Parfait R, Cocito C: Lasting damage to bacterial ribosomes by reversibly bound virginiamycin M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980, 77: 5492-5496.

Canu A, Leclercq R: Overcoming bacterial resistance by dual target inhibition: the case of streptogramins. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2001, 1: 215-225.

Vannuffel P, Cocito C: Mechanism of action of streptogramins and macrolides. Drugs. 1996, 51 Suppl 1: 20-30.

Wang G, Taylor DE: Site-specific mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori confer two types of resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998, 42: 1952-1958.

Vester B, Douthwaite S: Domain V of 23S rRNA contains all the structural elements necessary for recognition by the ErmE methyltransferase. J Bacteriol. 1994, 176: 6999-7004.

Vannuffel P, Di Giambattista M, Morgan EA, Cocito C: Identification of a single base change in ribosomal RNA leading to erythromycin resistance. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267: 8377-8382.

Vannuffel P, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C: Chemical probing of a virginiamycin M-promoted conformational change of the peptidyl-transferase domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22: 4449-4453.

Vannuffel P, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C: The role of rRNA bases in the interaction of peptidyltransferase inhibitors with bacterial ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267: 16114-16120.

Tait-Kamradt A, Davies T, Cronan M, Jacobs MR, Appelbaum PC, Sutcliffe J: Mutations in 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein L4 account for resistance in pneumococcal strains selected in vitro by macrolide passage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000, 44: 2118-2125. 10.1128/AAC.44.8.2118-2125.2000.

Rodriguez-Fonseca C, Amils R, Garrett RA: Fine structure of the peptidyl transferase centre on 23 S-like rRNAs deduced from chemical probing of antibiotic-ribosome complexes. J Mol Biol. 1995, 247: 224-235. 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0135.

Porse BT, Kirillov SV, Awayez MJ, Garrett RA: UV-induced modifications in the peptidyl transferase loop of 23S rRNA dependent on binding of the streptogramin B antibiotic, pristinamycin IA. Rna. 1999, 5: 585-595. 10.1017/S135583829998202X.

Porse BT, Garrett RA: Sites of interaction of streptogramin A and B antibiotics in the peptidyl transferase loop of 23 S rRNA and the synergism of their inhibitory mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 1999, 286: 375-387. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2509.

Pioletti M, Schlunzen F, Harms J, Zarivach R, Gluhmann M, Avila H, Bashan A, Bartels H, Auerbach T, Jacobi C, Hartsch T, Yonath A, Franceschi F: Crystal structures of complexes of the small ribosomal subunit with tetracycline, edeine and IF3. Embo J. 2001, 20: 1829-1839. 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1829.

Pihlajamaki M, Kataja J, Seppala H, Elliot J, Leinonen M, Huovinen P, Jalava J: Ribosomal mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 654-658. 10.1128/AAC.46.3.654-658.2002.

Pernodet JL, Boccard F, Alegre MT, Blondelet-Rouault MH, Guerineau M: Resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramin type B antibiotics due to a mutation in an rRNA operon of Streptomyces ambofaciens. Embo J. 1988, 7: 277-282.

Parfait R, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C: Competition between erythromycin and virginiamycin for in vitro binding to the large ribosomal subunit. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981, 654: 236-241. 10.1016/0005-2787(81)90177-5.

Kirillov SV, Porse BT, Garrett RA: Peptidyl transferase antibiotics perturb the relative positioning of the 3'-terminal adenosine of P/P'-site-bound tRNA and 23S rRNA in the ribosome. Rna. 1999, 5: 1003-1013. 10.1017/S1355838299990568.

Di Giambattista M, Chinali G, Cocito C: The molecular basis of the inhibitory activities of type A and type B synergimycins and related antibiotics on ribosomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989, 24: 485-507.

Depardieu F, Courvalin P: Mutation in 23S rRNA responsible for resistance to 16-membered macrolides and streptogramins in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001, 45: 319-323. 10.1128/AAC.45.1.319-323.2001.

Cocito C, Chinali G: Molecular mechanism of action of virginiamycin-like antibiotics (synergimycins) on protein synthesis in bacterial cell-free systems. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985, 16 Suppl A: 35-52.

Chinali G, Di Giambattista M, Cocito C: Ribosome protection by tRNA derivatives against inactivation by virginiamycin M: evidence for two types of interaction of tRNA with the donor site of peptidyl transferase. Biochemistry. 1987, 26: 1592-1597.

Pereyre S, Gonzalez P, De Barbeyrac B, Darnige A, Renaudin H, Charron A, Raherison S, Bebear C, Bebear CM: Mutations in 23S rRNA account for intrinsic resistance to macrolides in Mycoplasma hominis and Mycoplasma fermentans and for acquired resistance to macrolides in M. hominis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002, 46: 3142-3150. 10.1128/AAC.46.10.3142-3150.2002.

Kehoe LE, Snidwongse J, Courvalin P, Rafferty JB, Murray IA: Structural basis of Synercid (quinupristin-dalfopristin) resistance in Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 29963-29970. 10.1074/jbc.M303766200.

Choi KM, Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Brimacombe R: Flexibility of the nascent polypeptide chain within the ribosome--contacts from the peptide N-terminus to a specific region of the 30S subunit. Eur J Biochem. 1998, 255: 409-413. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550409.x.

Harms J, Schluenzen F, Zarivach R, Bashan A, Gat S, Agmon I, Bartels H, Franceschi F, Yonath A: High resolution structure of the large ribosomal subunit from a mesophilic eubacterium. Cell. 2001, 107: 679-688. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00546-3.

Green R, Samaha RR, Noller HF: Mutations at nucleotides G2251 and U2585 of 23 S rRNA perturb the peptidyl transferase center of the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 1997, 266: 40-50. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0780.

Wower J, Kirillov SV, Wower IK, Guven S, Hixson SS, Zimmermann RA: Transit of tRNA through the Escherichia coli ribosome. Cross-linking of the 3' end of tRNA to specific nucleotides of the 23 S ribosomal RNA at the A, P, and E sites. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 37887-37894. 10.1074/jbc.M005031200.

Bocchetta M, Xiong L, Mankin AS: 23S rRNA positions essential for tRNA binding in ribosomal functional sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998, 95: 3525-3530. 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3525.

Porse BT, Thi-Ngoc HP, Garrett RA: The donor substrate site within the peptidyl transferase loop of 23 S rRNA and its putative interactions with the CCA-end of N-blocked aminoacyl-tRNA(Phe). J Mol Biol. 1996, 264: 472-483. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0655.

Moazed D, Noller HF: Sites of interaction of the CCA end of peptidyl-tRNA with 23S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991, 88: 3725-3728.

Bashan A, Agmon I, Zarivach R, Schluenzen F, Harms J, Berisio R, Bartels H, Franceschi F, Auerbach T, Hansen HA, Kossoy E, Kessler M, Yonath A: Structural basis of the ribosomal machinery for peptide bond formation, translocation, and nascent chain progression. Mol Cell. 2003, 11: 91-102. 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00009-1.

Hansen JL, Schmeing TM, Moore PB, Steitz TA: Structural insights into peptide bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99: 11670-11675. 10.1073/pnas.172404099.

Agmon I, Auerbach T, Baram D, Bartels H, Bashan A, Berisio R, Fucini P, Hansen HA, Harms J, Kessler M, Peretz M, Schluenzen F, Yonath A, Zarivach R: On peptide bond formation, translocation, nascent protein progression and the regulatory properties of ribosomes. Eur J Biochem. 2003, 270: 2543-2556. 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03634.x.

Cannone JJ, Subramanian S, Schnare MN, Collett JR, D'Souza LM, Du Y, Feng B, Lin N, Madabusi LV, Muller KM, Pande N, Shang Z, Yu N, Gutell RR: The Comparative RNA Web (CRW) Site: an online database of comparative sequence and structure information for ribosomal, intron, and other RNAs: Correction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002, 3: 15-10.1186/1471-2105-3-15.

Otwinowski Z, Minor W: Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997, 276: 307-326.

Bailey S: The Ccp4 Suite - Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994, 50: 760-763. 10.1107/S0907444993011898.

Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL: Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998, 54: 905-921. 10.1107/S0907444998003254.

Carson M: Ribbons. Method Enzymol. 1997, 277: 493-505.

Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM: Ligplot - a Program to Generate Schematic Diagrams of Protein Ligand Interactions. Protein Eng. 1995, 8: 127-134.

Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE: The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28: 235-242. 10.1093/nar/28.1.235.

Acknowledgements

The dalfopristin coordinates were kindly provided by John Rafferty prior to publication. We thank the members of the ribosome groups in Hamburg, Germany (MPG-ASMB), in Berlin, Germany (MPI for Molecular Genetics) and Rehovot, Israel (Weizmann Institute) for their invaluable contributions. Special thanks go to DN Wilson, F Franceschi and A Mankin for their critical comments on the manuscript. These studies could not be performed without the excellent support by the staff of the synchrotron radiation facilities ID14-2/4 at ESRF and the staff at the SBC beamline ID-19, particularly by Stephen L. Ginell. Use of the Argonne National Laboratory Structural Biology Center beamlines at the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under Contract No. W-31-109-ENG-38. Support was provided by the Max-Planck-Society, the US National Institutes of Health (GM34360), the German Ministry for Science and Education (BMBF Grant 05-641EA) and the Kimmelman Center for Macromolecular Assembly at the Weizmann Institute. AY holds the Helen and Martin S. Kimmel Professorial Chair.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

JMH modelled the structure and produced the images. FS performed the computational tasks and drafted the manuscript. PF provided the materials and crystals used in this study. FS and HB collected and processed the x-ray data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jörg M Harms, Frank Schlünzen contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Harms, J.M., Schlünzen, F., Fucini, P. et al. Alterations at the peptidyl transferase centre of the ribosome induced by the synergistic action of the streptogramins dalfopristin and quinupristin . BMC Biol 2, 4 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-2-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-2-4