Abstract

Background

At the beginning of the transcription process, the RNA polymerase (RNAP) core enzyme requires a σ-factor to recognize the genomic location at which the process initiates. Although the crucial role of σ-factors has long been appreciated and characterized for many individual promoters, we do not yet have a genome-scale assessment of their function.

Results

Using multiple genome-scale measurements, we elucidated the network of σ-factor and promoter interactions in Escherichia coli. The reconstructed network includes 4,724 σ-factor-specific promoters corresponding to transcription units (TUs), representing an increase of more than 300% over what has been previously reported. The reconstructed network was used to investigate competition between alternative σ-factors (the σ70 and σ38 regulons), confirming the competition model of σ substitution and negative regulation by alternative σ-factors. Comparison with σ-factor binding in Klebsiella pneumoniae showed that transcriptional regulation of conserved genes in closely related species is unexpectedly divergent.

Conclusions

The reconstructed network reveals the regulatory complexity of the promoter architecture in prokaryotic genomes, and opens a path to the direct determination of the systems biology of their transcriptional regulatory networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The RNA polymerase (RNAP) core enzyme (E) for bacterial transcription is a catalytic multi-subunit complex (α2ββ′ω), capable of transcribing portions of the DNA template into RNA transcripts. At the beginning of the transcribing process, the RNAP core enzyme requires a σ-factor to recognize the genomic location at which the process initiates [1–3] (Figure 1a). Then σ-factor, a single dissociable subunit, binds to E, forming a holoenzyme (Eσx, x for each σ-factor) and orchestrates initiation of promoter-specific transcription [1]. To date, one housekeeping σ-factor σ70 (rpoD) and six alternative σ-factors σ54, σ38, σ32, σ28, σ24, and σ19 (rpoN, rpoS, rpoH, fliA, rpoE, and fecI, respectively) have been described in Escherichia coli. Although the importance of σ-factors and their role in the function of the RNAP and bacterial transcription are well known, we do not yet have a genome-wide understanding of the network of regulatory interactions that the σ-factors comprise in any species. With systems biology and genome-scale science emerging and describing the phenotypic functions of bacteria, it is now possible to comprehensively elucidate the structure of the σ-factor network. Here, we present the results from a systems approach that integrates multiple genome-scale measurements to reconstruct the regulatory network of σ-factor-gene interactions in E. coli. This reconstruction is provided here as a resource for the scientific community.

Molecular basis of transcription and a reconstruction of σ-factor-transcription unit gene ( σ-TUG) network from multi-omic experimental datasets. (a) Diagram shows bacterial transcription process by an RNA polymerase (RNAP) core enzyme and an associated σ-factor. (b) Four-step process of multi-omic data integration to reconstruct the σ-TUG network. First, we identified RNAP-binding regions (RNAP map) and σ-factor binding regions (σ map) from RpoB and σ-factor chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray (ChIP-chip) data (the missing σ24 binding information was taken from a public database [6]), resulting in the genome-wide holoenzyme binding map (Eσ map). The Eσ map was then combined with experimental transcription start site (TSS) information (TSS map), resulting in he strand-specific promoter map (P-map), which was integrated with previously reported TU information [7], resulting in the σ-network. With this σ-network, we then performed further analysis, such as network reprogramming, motif analysis, promoter overlapping, and alternative TSS usage. Subfigure I: IOPR, intensively overlapped promoter region; OPR, overlapped promoter region; SPR, single promoter region; Orphan, orphan promoter region. Subfigure III and IV: green and brown circles represent σ70 and σ38, yellow circles represent TUs, and red dots represent genes. Edges show regulatory interactions between elements. (c) Datasets used for σ-TUG network reconstruction: ChIP-chip dataset with RNAP and six σ-factors, and the TSS dataset. The TSS dataset for exponential phase was taken from a previous study [9].TSS subpanel: exp, exponential phase; stat, stationary phase; heat, heat shock; gln, alternative nitrogen source with glutamine. (d) Magnified examples of rpoD (left panel, genomic region ranging from 3,196 to 3,214 kbp), fecI and fecRAB (right panel, genomic region ranging from 4,494 to 4,517 kbp).

Results and discussion

Determination of the genome-wide map of holoenzyme binding

To capture the first step of the transcription cycle, which is the formation of the Eσx-promoter complex, we obtained genome-wide location profiles and integrated the identified RNAP and σ-factor binding sites, leading to a reconstruction of a genome-scale Eσ-binding region map (Figure 1b). A genome-wide static map of the entire group of Eσx-binding sites (Eσx map) was determined by employing chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray (ChIP-chip) of rifampicin-treated cells (Figure 1c), revealing the active promoter regions in vivo across the E. coli genome [4, 5] (see Methods). A total of 2,129 Eσx-binding regions were identified, consisting of 727 (34.1%) for the leading strand, 755 (35.5%) for the lagging strand, and 647 (30.4%) for both strands (that is, divergent promoter regions) (see Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Although the construction of the Eσx map is informative, it is not sufficient to produce the σ-specific Eσ-binding map, in which the promoter-specific role of the σ-factor is detailed [6]. We thus deployed ChIP-chip assays for the direct identification of the locations of σ-factor binding across the E. coli genome. We analyzed E. coli cells grown to mid-logarithmic phase or to stationary phase under multiple growth conditions (see Additional file 2: Table S1). Using data from biological duplicate or triplicate experiments for each σ-factor ChIP-chip (36 experiments in total), we identified 1,643 targets for σ70, 903 targets for σ38, 312 targets for σ32, 180 targets for σ54, 51 targets for σ28, and 7 targets for σ19 (Figure 1c; Figure 2a; see Additional file 3: Table S2; see Additional file 4: Table S3). We were not able to obtain dataset for σ24, and the missing dataset was supplemented by incorporating 65 σ24 promoter regions from RegulonDB [6]. For validation, we compared the σ-factor binding regions with the previously reported promoters regulated by each σ-factor [6] (Figure 1d; see Additional file 5: Table S5). Overall, we identified 86% of the previously reported binding sites and 2,465 new σ-factor binding regions, extending the current knowledge by over 300% (see Additional file 5: Table S5).

Properties of the reconstructed σ-factor network in Escherichia coli. (a) Extensive overlapping between σ-factor binding sites. For each σ-factor, σ70, σ38, σ54, σ32, σ28, σ24, and σ19, we identified 1,643, 903, 180, 312, 65, 51, and 7 binding regions, respectively. The number of binding regions overlapping between any two σ-factors is shown. For instance, 805 binding regions that were bound by both σ70 and σ38 were identified. (b) Number of promoters bound by multiple σ-factors showed a complex overlap between different σ-factors, indicating complicated alternative σ-factor usage. (c) A regulatory network between σ-factors in E. coli, in which σ70 and σ38 regulate expression of most of the seven σ-factors; σ70 and σ24 auto-regulate themselves. (d) Reconstruction of a three-layered network of σ-factors, transcription units (TUs), and genes. This network shows that many transcription start sites (TSSs) are shared by multiple σ-factors, suggesting possible competition between σ-factors for promoter binding. (e) Examples of thrLABC and hypBCDE-fhlA transcription units that are differently regulated by multiple σ-factors, and result in different TUs containing different sets of genes. For instance, TU001 is regulated by σ70 and contains four genes, thrLABC, while TU0005 is regulated by σ38 and had only two genes, thrB and thrC.

By integrating the entire Eσx and σ-factor binding regions, we obtained the genome-wide Eσ-binding region map (Eσ map) comprising 3,161 binding regions (see Additional file 6: Table S4). Next, each Eσ-binding site was classified into one of three categories depending on the number of σ-factors recruited to that site: single Eσ-binding promoter region (SPR), overlapped Eσ-binding promoter region (OPR), and intensively overlapped Eσ-binding promoter region (IOPR) (Figure 1b, d; Figure 2b). For instance, all σ-factors except σ19 were detected at the promoter region of the rpoD gene, which encodes σ70; however, only σ19 was found to bind to the promoter region of the fecABCDE operon, which encodes the ferric citrate outer membrane receptor and the ferric citrate ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter (Figure 1d). Over 48% of Eσ-binding regions identified in this study were overlapped or extensively overlapped binding regions, indicating that Eσ switching, or binding of alternative Eσ, at the same promoter region may be needed to ensure continued gene expression in response to environmental changes [2] (Figure 2a).

Determination of the genome-wide promoter map

We found that 69% of the Eσ-binding regions exhibited strand specificity, with the balance being observed as divergent promoter regions (see Additional file 1: Figure S1). Although the assignment of the RNAP-binding regions to each strand was achievable using the expression profiles [7], it was difficult to assign σ-factors directly to the promoter regions because information on the cis-acting sequence elements, such as the −10 and −35 boxes in the promoter regions, is not yet fully elucidated for each σ-factor. To identify the promoter elements more precisely with strand specificity and a better resolution than ChIP-chip, we performed transcription start site (TSS) profiling at the genome scale with a single nucleotide resolution. A genome-wide TSS map was generated from TSS profiling by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) followed by deep sequencing after 5′ triphosphate enrichment [8–10] for three conditions: stationary phase, heat shock, and alternative nitrogen source with glutamine. TSS profiling for exponential phase was taken from a previous study [9], and processed together with the other three datasets. The TSS map was then integrated with the Eσ map to build a strand-specific promoter map (P map) (Figure 1b-d).

Reconstruction of sigma factor regulons and their overlaps

The P map was combined with the transcription unit (TU) map [7], resulting in the σ-factor-TU gene (σ-TUG) network (Figure 2d, e; see Additional file 7: Table S6). A network of interactions between the σ-factors was extracted from the σ-TUG network (Figure 2c). σ70 and σ24 are the only σ-factors that auto-regulate themselves, and σ70 and σ38 regulate most of the other σ-factors, reflecting their roles as housekeeping σ-factors in exponential and stationary phase [1]. Gene essentiality data are available for E. coli[11], and only rpoD has been found to be an essential σ-factor. This network feature is consistent with the fact that σ70 regulates the highest number of σ-factors, including itself. In addition, σ70 has the largest regulon, and this cannot be replaced by the other σ-factors (Figure 2d).

The significant overlap of σ-factor regulons leads to the fundamental questions: what is the molecular basis for the overlap, and what are the consequences of having a complicated σ-factor network? Because each σ-factor has an individual ability to recognize cis-acting sequence elements in the promoter region (such as −10 box or −35 box), we analyzed the sequence motifs of the promoter regions (see Additional file 1: Figure S2). As in previous studies [12–14], the sequence motifs of σ70 and σ38 were found to have a similar −10 box sequence (TAtaaT and CTAtacT); however, unlike the σ70 sequence motif, σ38 did not have a distinctive −35 box. The similarity in the −10 box sequence motifs of the σ70- and σ38-specific promoters and the degenerate nature of the −35 box sequence of the σ38-specific promoters explains, in part, how a large overlap between σ70 and σ38 regulons is possible.

With the structure and molecular details of the σ-TUG network in hand, we were able to study its functional states. Because of the limited number of E complexes in a growing E. coli cell [1], each σ-factor should compete to achieve association with an E complex to initiate transcription. Thus, it becomes important which factor Eσx binds, and how frequently it does so [15]. We found that the promoter sets specific to each σ-factor overlap extensively, and a large number of promoters bound by multiple σ-factor share the same TSS (Figure 2a,d). These findings raise questions about the molecular mechanism of σ-factor competition for binding to the E complex and subsequently to the promoter, and how that affects transcription initiation.

Sigma factor competition in overlapped promoters

σ-factors are believed to act predominantly as positive effectors, as they recognize the cis-acting elements in promoters that enable the Eσx to bind. Interestingly, however, σ38 has a negative effect on the expression level of some genes, even though it acts mainly as a positive effector [16, 17]. To shed light on the molecular mechanisms of σ-factor competition by σ38, we performed ChIP-chip experiments for RpoB with wild type (WT) E. coli and its isogenic rpoS knock-out strain to obtain differential Eσx binding to the genome. The differential binding intensity of the Eσx to the promoters of 1,139 genes, whose transcription is directly affected by σ38, is shown in Figure 3a. If σ38-specific promoters were bound only by σ38, then the E complex recruited to those promoters would be very scarce. However, the majority of σ38-specific promoters showed significant levels of signaling for Eσx binding in the σ38 deletion strain, indicating recruitment of the Eσx and implying rescue of transcription activity (Figure 3a).

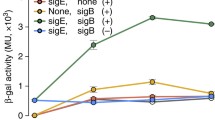

Competition between σ70and σ38in overlapping promoter regions. (a) Recruitment of RNA polymerase (RNAP) core enzyme to promoters upstream of 1,139 σ38-specific genes was recovered when rpoS was knocked out. RNAP binding intensity on the y-axis was the chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray (ChIP-chip), intensity; the three red lines represent the first, second, and third quantiles. (b) Comparison of transcriptional expression of genes in wild type (WT) and ΔrpoS strains. Of 1,139 genes with σ38-specific promoters,178 had up-regulated transcription (red background) and 291 had down-regulated transcription (blue background). (c) Expression level of σ70 and σ38 was measured at both th transcriptional and translational levels. The amount of σ70 was abundant in exponential and stationary phase, and so it was absent in rpoS. (d) After rpoS knock-out, up-regulated genes were more strongly bound by σ70 than down-regulated genes.

To confirm that the detected binding of the Eσx leads to transcription, we performed expression profiling with WT and rpoS knock-out strain cells under stationary phase conditions (Figure 3b; see Additional file 8: Table S7). Most genes having σ38-specific promoters were expressed. Of 1,139 genes with σ38-specific promoters, 178 (16%) showed up-regulated expression when rpoS was removed and 291 (26%) showed expression that was down-regulated more than two-fold (t-test P-value ≤0.05). The remaining 58% of the genes showed no statistical significance in expression (fold change <2) or were not expressed in either strain. In the absence of rpoS, σ38-specific promoters became active in transcription, leading to expression of the corresponding genes, but at a different level for 469 (41%) of these 1,139 genes.

Expression of genes with σ38-regulated genes was recovered when rpoS was knocked out; however, it is not known which of the other σ-factors is replacing the role of σ38. As σ70 shared the largest portion of promoters with σ38, it is reasonable to assume that σ70 would replace σ38 when σ38 is missing. In E. coli MC4100, it was reported that the amount of σ70 is in abundance during stationary phase [18]. Similarly, we found that E. coli K-12 MG1655 also showed high protein expression of σ70 during stationary phase in WT and ΔrpoS strain (Figure 3c, see Additional file 1 for detailed description). In addition, we examined how many genes bound by σ38 in the WT strain were bound by σ70 when rpoS was deleted. We found that about 89% of those genes was bound by σ70 when σ38 was missing, (see Additional file 1: Figure S3). This unexpectedly high rate of σ-factor substitution explains how the majority of genes directly bound by σ38 recovered their expression when rpoS was knocked out (Figure 3b). However, it is still unclear how some of those genes were up-regulated.

Because approximately 89% of these genes were bound by σ70, we measured the intensity of σ70 binding in ΔrpoS during stationary phase with ChIP-chip experiments, and compared the binding intensity between up-regulated and down-regulated genes (Figure 3d; see Additional file 1: Figure S4). This measurement showed that up-regulated genes were bound more strongly by σ70 (P-value of Wilcoxon rank sum test was 4.80 × 10-18), suggesting that strong σ70 binding resulted in increased transcription. This finding indicates that the presence of σ38 actually contributed to repressing the transcriptional expression of some genes, presumably by competition for shared promoters between σ70 and σ38.

Comparative analysis of the sigma factor network in closely related species

With the detailed reconstruction of the σ-TUG network in E. coli, we could now address the issue of the difference between such networks in closely related species. Genome-wide identification of TSSs of two gamma-Proteobacteria, E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, revealed that promoter regions upstream of orthologous genes are differently organized in the two species, resulting in different usage of TSSs [9]. As σ-factors recognize sequence elements of promoters, and they are directly upstream of TSSs, it is important to determine any differences in σ-factor binding patterns. Whereas the E. coli genome contains seven σ-factors, K. pneumoniae is known to have only five, missing fliA and fecI, which are found in E. coli. The five σ-factors that the two species have in common are highly conserved in terms of amino acid sequence similarity: 95.9% for rpoD, 98.5% for rpoS, 89.8% for rpoN, 95.1% for rpoH, and 96.3% for rpoE. Promoter sequence motifs examined from the TSSs were found to be identical between E. coli and K. pneumoniae, suggesting that the sequence motifs for each orthologous σ-factor are identical [9, 19]. However, the different organization of upstream regulatory regions of the two species and the different pattern of transcription initiation indicates the possibility of significantly diverse σ-factor binding.

To investigate the binding patterns of two major σ-factors, rpoD and rpoS, we analyzed ChIP-chip datasets for σ70 under exponential phase and σ38 under stationary phase grown in glucose minimal media as described previously [19]. E. coli and K. pneumoniae have 4,513 and 5,305 genes, respectively, and 2,876 coding genes were defined as orthologs by two-way reciprocal alignment. Binding of σ70 and σ38 under specified conditions upstream of those orthologous genes was analyzed and clustered (Figure 4a). Of the 2,876 orthologous genes, 60% showed the same binding patterns (584 had both σ factors bound, 213 had σ70 bound, 102 had σ38 bound, and 847 had neither factor bound). These two closely related bacteria, E. coli and K. pneumoniae, share the majority of their gene contents, with most of the open reading frames having highly conserved sequences. However, conserved genes showed significantly different σ-factor binding patterns, indicating diverse gene regulation by different transcription initiation (Figure 4c,d). Interestingly, in some cases, altered binding of σ-factors was associated with changes in TU organization, suggesting even more diverse regulation between the two species. Although two major σ-factors were found to bind differently upstream of orthologous genes, regulation between σ-factors remained unchanged, except for the two missing σ-factors, fliA and fecI, in K. pneumoniae (see Additional file 1: Figure S5). Thus, regulation of gene expression by σ-factors may evolve faster than regulation among the σ-factors themselves.

Conservation and divergence in transcriptional regulation by σ-factors. (a) Clustering σ-factor binding patterns revealed conserved and divergent transcriptional regulation of 2,876 orthologous genes. (b) crp is regulated by σ70 and σ38 in both species, showing regulation conservation. (c) In Esherichia coli, cutA is a part of the dcuA-cutA-dipZ transcription unit (TU) and is regulated by σ70 and σ38, while cutA in Klebsiella pneumoniae is the first gene in its TU, and is directly bound by σ70. (d) In K. pneumoniae, panD is a part of the panBCD TU, which is regulated by σ70. However, in E. coli, panD is separated from panBC by yadD, making another distinct TU. These two TUs are both regulated by σ70. (e) A genomic region containing ydeA and marC in both species was inverted, and this genomic inversion was accompanied by a transcription regulation switch between σ70 and σ38.

Conclusions

Genome-scale measurements enabled us to reconstruct the σ-TUG network in E. coli K-12 MG1655. This network is at the core of transcriptional regulation in bacteria. Its reconstruction has enabled the assessment of its topological characteristics, functional states, and limited comparison with related species. With the integration of a growing body of experimental data on transcription factor (TF) binding and activity, the resource provided here opens up the possibility of developing a comprehensive reconstruction of the entire transcriptional regulatory network in E. coli, which would simultaneously describe the function of σ-factors and TFs that produce the entire expression state of the organism.

Methods

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions

E. coli K-12 MG1655 and its isogenic knock-out strains were used in this study. The deletion mutants (ΔrpoS and ΔrpoN) were generated by a λ Red and FLP-mediated site-specific recombination system [20]. E. coli cells were harvested at mid-exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm) of approximately 0.5) with the exception of stationary phase experiments (OD600nm approximately 1.5). Glycerol stocks of E. coli strains were inoculated into M9 or W2 minimal media [21] (for nitrogen-limiting condition) with glucose (2 g/l) and cultured overnight at 37°C with constant agitation. Cultures were then diluted 1:100 into 50 ml of fresh minimal media. and cultured at 37°C to appropriate cell density. For heat-shock experiments, cells were grown to mid-exponential phase at 37°C. and half of the culture was used as a control, while the remaining culture was transferred into pre-warmed (50°C) media and incubated for 10 minutes. For nitrogen-limiting condition, ammonium chloride in the minimal media was replaced by glutamine (2 g/l).

Total RNA isolation

Cell (3 ml) culture was mixed with 6 ml RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Samples were mixed immediately by vortexing for 5 seconds, incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was decanted, and any residual supernatant was removed by inverting the tube once onto a paper towel. Total RNA samples were then isolated using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were then quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), and the quality of the isolated RNA was checked by visualization on agarose gels and by measuring the ratio of the absorbance at 260 and 280 nm (A260/A280 ratio) of the sample (>1.8).

Transcriptome analysis

Transcriptome datasets with oligonucleotide tiling microarrays for WT E. coli K-12 MG1655 grown under four conditions (exponential phase, stationary phase, heat shock, and nitrogen-limiting condition), were taken from a previous study [7]. In order to obtain a transcriptome dataset for E. coli deletion mutant ΔrpoS, a previously described protocol [9] was adapted for the deletion mutant in the current study. Briefly, 10 μg of purified total RNA sample was reverse transcribed to cDNA with amino-allyl dUTP. The amino-allyl-labeled cDNA samples were then coupled with Cy3 monoreactive dyes (Amersham). Cy3-labeled cDNAs were fragmented to the 50 to 300 bp range with DNase I (Epicentre). High-density oligonucleotide tiling arrays consisting of 371,034 50-mer probes spaced 25 bp apart across the whole E. coli genome were used (Roche Nimblegen). Hybridization, washing, and scanning were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Three biological replicates were used for stationary phase in glucose minimal media. Probe level data were normalized with a robust multiarray analysis (RMA) algorithm without background correction, as implemented in NimbleScan 2.4 software.

TSS-sequencing by modified 5′ RACE, and deep sequencing

The raw TSS dataset for exponential phase was taken from a previous study [9]. For the other three conditions (stationary phase, heat shock, and nitrogen-limiting condition), the previously described TSS determination protocol [9] was adapted for E. coli K-12 MG1655. To enrich intact 5′ tri-phosphorylated mRNAs from the total RNA, 5′ mono-phosphorylated rRNA and any degraded mRNA were removed by treatment with a Terminator 5′-Phosphate Dependent Exonuclease (Epicentre) at 30°C for 1 hour. The reaction mixture consisted of 10 μg purified total RNA, 1 μl terminator exonuclease, reaction buffer, and RNase-free water up to total 20 μl. The reaction was terminated by adding 1 μl of 100 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Intact tri-phosphorylated RNAs were precipitated by adding 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2), 3 volumes of ethanol, and 2 μl of 20 mg/ml glycogen. RNA was precipitated at −80°C for 20 minutes and pelleted, washed with 70% ethanol, dried in Speed-Vac for 7 minutes without heat, and resuspended in 20 μl nuclease free water. The tri-phosphorylated RNA was then treated with RNA 5′-Polyphosphatase (Epicentre) to generate 5′-end mono-phosphorylated RNA for adaptor ligation. The RNA sample from the previous step was mixed with 2 μl 10× reaction buffer, 0.5 μl SUPERase-In (Ambion), 1 μl RNA 5′-Polyphosphatase, and RNase-free water up to 20 μl. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and reaction was stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction. Ethanol precipitation was carried out for isolating the RNA as described above. To ligate the 5′ small RNA adaptor (Table 1) to the 5′-end of the mono-phosphorylated RNA, the enriched RNA samples were incubated with 100 μM of the adaptor and 2.5 U of T4 RNA ligase (New England Biolabs). cDNAs were synthesized using the adaptor-ligated mRNAs as template using a modified small RNA RT primer from Illumina (Table 1) and Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). The RNA was mixed with 25 μM modified small RNA RT primer and incubated at 70°C for 10 minutes and then at 25°C for 10 minutes. RT was carried out at 25°C for 10 minutes, 37°C for 60 minutes, and 42°C for 60 minutes, followed by incubation at 70°C for 10 minutes. The RT reaction mixture consisted of 5× firstt strand buffer; 0.01 M DTT, 10 mM dNTP mix, 30 U SUPERase•In (Ambion), and 1500 U SuperScript II (Invitrogen). After the reaction, RNA was hydrolyzed by adding 20 μl of 1 N NaOH and incubating the mixture at 65°C for 30 minutes. The reaction mixture was neutralized by adding 20 μl of 1 N HCl. The cDNA samples were amplified using a mixture of 1 μl cDNA, 10 μl Phusion HF buffer (NEB), 1 μl dNTPs (10 mM), 1 μl SYBR Green (Qiagen), 0.5 μl HotStart Phusion (NEB), and 5 pM small RNA PCR primer mix. The amplification primers used are shown in Table 1. The PCR mixture was denatured at 98°C for 30 seconds and cycled to 98°C for 10 seconds, 57°C for 20 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds. Amplification was monitored by a LightCycler (Bio-Rad) and stopped at the beginning of the saturation point. Amplified DNA was run on a 6% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) gel (Invitrogen) by electrophoresis, and DNA fragments ranging from 100 to 300 bp were size-fractionated. Gel slices were dissolved in two volumes of EB buffer (Qiagen) and 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2). The amplified DNA was then ethanol-precipitated and resuspended in 15 μl DNase-free water (USB). The final samples were then quantified using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Sequencing, data processing, and mapping

The data processing and mapping of the sequencing results to obtain potential TSSs was performed exactly as described previously [9]. In brief, the amplified cDNA libraries from two biological replicates for each condition were sequenced on an Illumina Genome Analyzer. Sequence reads for cDNA libraries were aligned to the E. coli K-12 MG1655 genome (NC_000913) using Mosaik [22] with the following arguments: hash size = 10, mismatach = 0, and alignment candidate threshold = 30 bp. Only reads that aligned to a unique genomic location were retained. Two biological replicates were processed separately, and only sequence reads presented in both biological replicates were considered for further processing. The genome coordinates of the 5′-end of these uniquely aligned reads were defined as potential TSSs, and of these, only TSSs with the strongest signal within 10 bp window were kept, in order to remove possible noise signals. TSSs with signals that were 40% or greater of the strongest signal upstream of an annotated gene were considered as multiple TSSs. The strongest signal was defined as the potential TSS that had the highest number of reads out of all the TSSs upstream of an annotated gene. For further analysis, TSSs lying within RNAP-binding regions (see Additional file 4: Table S3) were used for integration with σ-factor binding information.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray analysis

Briefly, the immunoprecipitated RNAP-associated DNA fragments were fluorescently labeled and hybridized to a high-density oligonucleotide tiling microarray representing the entire E. coli genome [5]. To identify in vivo binding regions of RNAP complex and six σ-factors (σ70, σ54, σ38, σ32, σ28, and σ19), we isolated DNA fragments bound to those RNAP subunits from formaldehyde-crosslinked E. coli cells, using ChIP with six different antibodies that specifically recognize each subunit (NeoClone). An E. coli strain harboring RpoH-8myc was constructed as previously described [23, 24], and used for the σ38 ChIP-chip with anti-c-myc antibody (9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Cells were grown under appropriate conditions (see Additional file 2: Table S1) and harvested. The immunoprecipitation (IP) DNA and mock-IP DNA were hybridized onto high-resolution whole-genome tiling microarrays, which contained a total of 371,034 oligonucleotides with 50-bp probes overlapping by 25 bp on both forward and reverse strands. Tiling microarrays were hybridized, washed, and scanned in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche NimbleGen). To increase the depth of the number of promoter regions identified, datasets were generated under multiple growth conditions with a total number of 45 ChIP-chip experiments (36 for σ-factors and 9 for RNAP), and analyzed (see Additional file 2: Table S1). We were not able to obtain results for the ChIP-chip experiment for σ24. This could be because the expression level of σ24 was not high enough, or the conditions were not appropriate to activate σ24. To remedy the missing dataset, we deployed known binding information for σ24 from the public database [25].

ChIP-chip data analysis

The analysis was performed, as previously described [7, 26]. In brief, TF-binding regions were identified by using the peak-finding algorithm built into the NimbleScan software (Roche NimbleGen). Processing of ChIP-chip data was performed in three steps: normalization, IP/mock-IP ratio computation (in log2 scale) and enriched-region identification. The log2 ratios of each spot in the microarray were calculated from the raw signals obtained from both Cy5 and Cy3 channels, and then the values were scaled by Tukey bi-weight mean. The log2 ratio of Cy5 (IP DNA) to Cy3 (mock-IP DNA) for each point was calculated from the signals, then, the bi-weight mean of this log2 ratio was subtracted from each point. Each log-ratio dataset (from duplicate or triplicate samples) was used to identify TF-binding regions using the software (width of sliding window = 300 bp). Our approach to identify the TF-binding regions was to first determine the binding locations from each dataset, and then combine the binding locations from at least five of six datasets to define a binding region, using the recently developed MetaScope visualization software and genome browser [27].

Western blotting

E. coli K-12 MG1655 and ΔrpoS deletion mutant cells were grown in M9 minimal media with 0.2% glucose, and were harvested from mid-exponential phase to stationary phase every 2 hours. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and were lysed with lysozyme in a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA. The supernatant was decanted after centrifugation to remove unlysed cells. The concentration of total protein in the lysate was measured with Qubit Protein Assay Kit (invitrogen), and 5 μg of total protein sample were mixed with 4× SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer (Invitrogen) and 10 mM DTT, then boiled at 90°C for 5 minutes. The boiled samples were separated by electrophoresis with 10% Bis-Tris gel in MOPS buffer, and transferred onto Hybond-ECL membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was briefly washed in TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (1× TBS-T) for 5 minutes on a rocker, and then treated with 2% skim milk in TBS-T buffer for 1 hour with gentle shaking. The membrane was washed twice with TBS-T for 5 minutes each on a rocker, and then it was sliced into three pieces. with RpoB, σ70, and σ38 in each slice. Sliced membranes were treated with anti-RpoB, anti-σ70, and anti-σ38 antibodies (1:10,000 dilution; NeoClone) for 1 hour on a rocker. The membrane slices were washed once in TBS-T for 15 minutes, followed by three washes of 5 minutes each, and then treated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000 dilution; Amersham Bioscience) in dilution for 30 minutes on a rocker, followed by one wash in TBS-T for 15 minutes and three washes of 5 minutes each. Chemiluminescent detection was applied to peroxidase conjugates on membrane to detect the amount of RpoB, σ70, and σ38.

Availability of supporting data

All raw and processed data files have been deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus (accession number GSE46740).

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

ATP-binding cassette

- ChIP:

-

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ChIP-chip:

-

chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray

- E:

-

RNA polymerase core enzyme

- IOPR:

-

Intensively overlapped Eσ-binding promoter region

- IP:

-

immunoprecipitation

- OPR:

-

Overlapped Eσ-binding promoter region

- RACE:

-

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- RMA:

-

Robust multiarray analysis

- RNAP:

-

RNA polymerase

- SPR:

-

Single Eσ-binding promoter region

- TBE:

-

Tris-borate-EDTA

- TF:

-

transcription factor

- TSS:

-

Transcription start site

- TU:

-

Transcription unit

- σ-TUG:

-

σ-factor-transcription unit gene

- WT:

-

wild type.

References

Ishihama A: Functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000, 54: 499-518. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.499.

Osterberg S, del Peso-Santos T, Shingler V: Regulation of alternative sigma factor use. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011, 65: 37-55. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134219.

Sharma UK, Chatterji D: Transcriptional switching in Escherichia coli during stress and starvation by modulation of sigma activity. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010, 34: 646-657.

Yamamoto K, Hirao K, Oshima T, Aiba H, Utsumi R, Ishihama A: Functional characterization in vitro of all two-component signal transduction systems from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280: 1448-1456.

Herring CD, Raffaelle M, Allen TE, Kanin EI, Landick R, Ansari AZ, Palsson BO: Immobilization of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and location of binding sites by use of chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarrays. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187: 6166-6174. 10.1128/JB.187.17.6166-6174.2005.

Gama-Castro S, Jimenez-Jacinto V, Peralta-Gil M, Santos-Zavaleta A, Penaloza-Spinola MI, Contreras-Moreira B, Segura-Salazar J, Muniz-Rascado L, Martinez-Flores I, Salgado H, Regulon DB, et al: (Version 6.0): gene regulation model of Escherichia coli K-12 beyond transcription, active (experimental) annotated promoters and Textpresso navigation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36: D120-D124. 10.1093/nar/gkn491.

Cho BK, Zengler K, Qiu Y, Park YS, Knight EM, Barrett CL, Gao Y, Palsson BO: The transcription unit architecture of the Escherichia coli genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2009, 27: 1043-1049. 10.1038/nbt.1582.

Qiu Y, Cho BK, Park YS, Lovley D, Palsson BO, Zengler K: Structural and operational complexity of the Geobacter sulfurreducens genome. Genome Res. 2010, 20: 1304-1311. 10.1101/gr.107540.110.

Kim D, Hong JS, Qiu Y, Nagarajan H, Seo JH, Cho BK, Tsai SF, Palsson BO: Comparative analysis of regulatory elements between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae by genome-wide transcription start site profiling. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8: e1002867-10.1371/journal.pgen.1002867.

Sharma CM, Hoffmann S, Darfeuille F, Reignier J, Findeiss S, Sittka A, Chabas S, Reiche K, Hackermuller J, Reinhardt R, et al: The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 2010, 464: 250-255. 10.1038/nature08756.

Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H: Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol. 2006, 2: 0008-

Typas A, Becker G, Hengge R: The molecular basis of selective promoter activation by the sigmaS subunit of RNA polymerase. Mol Microbiol. 2007, 63: 1296-1306. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05601.x.

Typas A, Hengge R: Role of the spacer between the −35 and −10 regions in sigmas promoter selectivity in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2006, 59: 1037-1051. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04998.x.

Weber H, Polen T, Heuveling J, Wendisch VF, Hengge R: Genome-wide analysis of the general stress response network in Escherichia coli: sigmaS-dependent genes, promoters, and sigma factor selectivity. J Bacteriol. 2005, 187: 1591-1603. 10.1128/JB.187.5.1591-1603.2005.

Ishihama A: Promoter selectivity of prokaryotic RNA polymerases. Trends Genet. 1988, 4: 282-286. 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90170-9.

Loewen PC, Hu B, Strutinsky J, Sparling R: Regulation in the rpoS regulon of Escherichia coli. Can J Microbiol. 1998, 44: 707-717. 10.1139/cjm-44-8-707.

Farewell A, Kvint K, Nystrom T: Negative regulation by RpoS: a case of sigma factor competition. Mol Microbiol. 1998, 29: 1039-1051. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00990.x.

Jishage M, Ishihama A: Regulation of RNA polymerase sigma subunit synthesis in Escherichia coli: intracellular levels of sigma 70 and sigma 38. J Bacteriol. 1995, 177: 6832-6835.

Seo JH, Hong JS, Kim D, Cho BK, Huang TW, Tsai SF, Palsson BO, Charusanti P: Multiple-omic data analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae MGH 78578 reveals its transcriptional architecture and regulatory features. BMC Genomics. 2012, 13: 679-10.1186/1471-2164-13-679.

Datsenko KA, Wanner BL: One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97: 6640-6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297.

Powell BS, Court DL, Inada T, Nakamura Y, Michotey V, Cui X, Reizer A, Saier MH, Reizer J: Novel proteins of the phosphotransferase system encoded within the rpoN operon of Escherichia coli, Enzyme IIANtr affects growth on organic nitrogen and the conditional lethality of an erats mutant. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270: 4822-4839. 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4822.

MOSAIK: MosaikAligner. http://code.google.com/p/mosaik-aligner,

Cho BK, Barrett CL, Knight EM, Park YS, Palsson BO: Genome-scale reconstruction of the Lrp regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105: 19462-19467. 10.1073/pnas.0807227105.

Cho BK, Knight EM, Barrett CL, Palsson BO: Genome-wide analysis of Fis binding in Escherichia coli indicates a causative role for A-/AT-tracts. Genome Res. 2008, 18: 900-910. 10.1101/gr.070276.107.

Salgado H, Peralta-Gil M, Gama-Castro S, Santos-Zavaleta A, Muniz-Rascado L, Garcia-Sotelo JS, Weiss V, Solano-Lira H, Martinez-Flores I, Medina-Rivera A, et al: RegulonDB v8.0: omics data sets, evolutionary conservation, regulatory phrases, cross-validated gold standards and more. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41: D203-D213. 10.1093/nar/gks1201.

Cho BK, Federowicz S, Park YS, Zengler K, Palsson BO: Deciphering the transcriptional regulatory logic of amino acid metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2012, 8: 65-71.

Systems Biology Research Group: MetaScope: a genome browser implementing interactive visualization and data integration for analyzing and integrating genome-scale multiple -omic data. http://systemsbiology.ucsd.edu/Downloads/MetaScope,

Acknowledgements

We thank Hojung Nam and Qiu Yu for the assistance for the data processing, and Marc Abrams for helpful assistance in writing the manuscript. This research was supported by US National Institutes of Health (through grants GM062791 and GM057089), Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability, and Samsung Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BKC, DK, and BOP conceived the idea and designed the research. BKC, DK, and EMK performed the experiments. D, and BKC analyzed the data. DK, BKC, KZ, and BOP wrote the paper, with comments from other authors. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Byung-Kwan Cho, Donghyuk Kim contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

12915_2014_747_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Strand specificity of RNA polymerase (RNAP) binding. Figure S2. Sequence motifs of σ-factors. Figure S3. The majority of σ38-specific promoters were bound by σ70 when rpoS is missing. Figure S4. Examples of up-regulated and down-regulated genes when rpoS was knocked out. Figure S5. Comparison of transcriptional regulation by two major σ-factors, σ70 and σ38, in two closely related bacteria. Figure S6. Comparison of transcriptional level of σ-factors and their anti-σ-factors. Figure S7. Purine and pyrimidine preferences at transcription start site (TSS) and −1 site. Figure S8. Number of TSSs found in one or multiple conditions. Figure S9. Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) clustering analysis of σ-factor regulons. (DOCX 1 MB)

12915_2014_747_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 2: Table S1: Escherichia coli strains and culture conditions for chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray (ChIP-chip) experiments. (XLSX 12 KB)

12915_2014_747_MOESM7_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 7: Table S6: Reconstructed σ-factor-transcription unit gene (σ-TUG) network in Escherichia coli.(XLSX 317 KB)

12915_2014_747_MOESM8_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 8: Table S7: Transcription levels of Escherichia coli genes in the wild type and the ΔrpoS strain. (XLSX 484 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, BK., Kim, D., Knight, E.M. et al. Genome-scale reconstruction of the sigma factor network in Escherichia coli: topology and functional states. BMC Biol 12, 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-12-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-12-4