Abstract

Background

Newer approaches for classifying gradations of pediatric obesity by level of body mass index (BMI) percentage above the 95th percentile have recently been recommended in the management and tracking of obese children. Examining the prevalence and persistence of severe obesity using such methods along with the associations with other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension is important for characterizing the clinical significance of severe obesity classification methods.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in an integrated healthcare delivery system to characterize obesity and obesity severity in children and adolescents by level of body mass index (BMI) percentage above the 95th BMI percentile, to examine tracking of obesity status over 2–3 years, and to examine associations with blood pressure. Moderate obesity was defined by BMI 100-119% of the 95th percentile and severe obesity by BMI ≥120% × 95th percentile. Hypertension was defined by 3 consecutive blood pressures ≥95th percentile (for age, sex and height) on separate days and was examined in association with obesity severity.

Results

Among 117,618 children aged 6–17 years with measured blood pressure and BMI at a well-child visit during 2007–2010, the prevalence of obesity was 17.9% overall and was highest among Hispanics (28.9%) and blacks (20.5%) for boys, and blacks (23.3%) and Hispanics (21.5%) for girls. Severe obesity prevalence was 5.6% overall and was highest in 12–17 year old Hispanic boys (10.6%) and black girls (9.5%). Subsequent BMI obtained 2–3 years later also demonstrated strong tracking of severe obesity. Stratification of BMI by percentage above the 95th BMI percentile was associated with a graded increase in the risk of hypertension, with severe obesity contributing to a 2.7-fold greater odds of hypertension compared to moderate obesity.

Conclusion

Severe obesity was found in 5.6% of this community-based pediatric population, varied by gender and race/ethnicity (highest among Hispanics and blacks) and showed strong evidence for persistence over several years. Increasing gradation of obesity was associated with higher risk for hypertension, with a nearly three-fold increased risk when comparing severe to moderate obesity, underscoring the heightened health risk associated with severe obesity in children and adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Data from U.S. population surveys demonstrate a significant increase in obesity prevalence among children age 2–19 years old, from 5.5% in 1976–1980[1] to 16.9% in 2007–2010[1, 2], with obesity defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 growth charts[3]. As obesity rates have climbed in all age groups[4–7], the prevalence of severe obesity has also risen, increasing from 1.1% to 5.1% in boys and 1.3% to 4.7% in girls from 1976–2006[7]. Historically, severe obesity in children has been described in broad terms, with fewer studies examining gradations of obesity severity in relation to potentially adverse secondary complications. Methods for classifying extremely high BMI have evolved in the past decade, related in part to the limited utility of BMI percentiles and Z scores where contraction of values occurs at the upper range[8]. As an alternative, expressing BMI as a percentage of the 95th BMI percentile has been recommended for characterizing and tracking children with high BMI[9–11], where a threshold of BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile has been used to define severe obesity[7, 9–12]. New growth charts with additional growth curves representing higher order BMI as a percentage of the 95th percentile have also been recently published[10, 11] and may allow for more precise stratification of risk among obese children.

The present study conducted in a contemporary, diverse population of children followed in routine pediatric clinical care settings was designed with three specific aims. First, we characterized obesity severity by expressing BMI as a percentage of the 95th BMI percentile for age and sex. Second, we examined obesity status over 2–3 years follow-up, to determine tracking of both obesity and severe obesity in children and early adolescents. Third, we applied these new obesity stratification criteria to examine the association of obesity severity and hypertension as a potential indicator of the degree of cardiovascular health risk.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research approved the study with ceding of oversight authority by the KPNC Institutional Review Board. A waiver of informed consent was obtained due to the nature of the study.

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is a large integrated healthcare delivery system providing comprehensive care for more than three million members annually. For this study, we examined data from a large retrospective multicenter study of pediatric hypertension[13], using a subcohort that included 117,936 children aged 6–17 years receiving care within three large KPNC subregions. Data pertaining to age, height, weight and blood pressure were obtained from the electronic medical record for the first (index) well child visit with measured height, weight and blood pressure between July 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010 as previously described[13]. Data for race/ethnicity, sex and membership were obtained from administrative databases.

Height was measured by stadiometer and weight was measured on a calibrated scale as part of routine clinical care. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2), with percentiles calculated from the year 2000 CDC growth charts and reference datasets[14] to classify children as normal weight or underweight (BMI <85th BMI-for-age percentile); overweight (BMI 85th-94th (94.9) BMI-for-age percentile); or obese (BMI ≥95th BMI-for-age percentile)[3, 4] as previously described[13, 15]. For the purposes of this study, obese children were further classified based on BMI expressed as a percentage above the 95th BMI percentile according to age and sex[9, 11], with a BMI 100-119% of the 95th percentile used to define moderate obesity and a BMI ≥120% of the 95th BMI percentile used to define severe obesity[7, 9, 12]. For children aged 6–13 years, a follow-up BMI was also examined when the child was 2–3 years older (available in 73.1% of subjects, requiring a minimum of 600 days between visits; 89.5% of follow-up visits were for well child care).

To address potential BMI errors in the electronic medical record for the index visit, we first excluded those with height flagged as “biologically implausible” by the CDC program[16] and those with height <91.4 or >213.4 cm, weight <9.1 or >272.2 kg, or BMI <10 or >120 kg/m2. Next, 540 growth charts were manually reviewed if the index anthropometric data met any of the following criteria: (1) high values of weight or BMI flagged as “biologically implausible” by the CDC program[16] (except adolescents 12–17 years old with another BMI <5% different from the index value); (2) severely obese children with another height, weight or BMI differing by >15-20% per year within 2 years; and (3) obese children with subsequent non-obese BMI. Review of these outlying values resulted in the exclusion of 97 children with data errors.

Blood pressure measurements were obtained using oscillometric devices as previously described[13], with levels classified according to the Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents[17]. Normal blood pressure was defined as a systolic and diastolic blood pressure <90th percentile, prehypertension was defined as a systolic or diastolic blood pressure between the 90th and <95th percentile (or blood pressure ≥120/80 mmHg for adolescents) and an elevated BP in the hypertension range was defined by a systolic or diastolic BP ≥95th percentile[17]. Among children and adolescents with an index (initial) elevated BP ≥95th percentile, hypertension was classified based on two additional consecutive BP measurements ≥95th percentile[17] or SBP ≥140 and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg for subsequent BP obtained at age ≥18 years and older (0.24% of the overall cohort) as previously described[13]. There were 730 (3.5% of the overall cohort) who did not have follow-up BP to allow final BP classification.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Means with standard deviation and medians with interquartile range for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables were computed. Differences between subgroups and classification methods were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. The trend in proportions across categories was examined using the Cochrane-Armitage test. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the independent relationship of obesity severity and elevated blood pressure, adjusting for differences in age, race/ethnicity and sex. These multivariable analyses, conducted in obese children, excluded 107 (0.5%) who received treatment with blood pressure lowering medication (the majority received clonidine or guanfacine, for presumably non-hypertensive indications) in the six months prior to the index well-child visit. A p-value of <0.05 was chosen as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

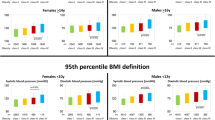

The final study population consisted of 117,618 children and adolescents aged 6–17 years with measured height, weight and blood pressure at well child visits between July 1, 2007 and December 31, 2010. Half (49.5%) were female and 55.3% were age 12–17 years old. There was substantial racial and ethnic diversity, with 31.3% white, 8.8% black, 26.2% Hispanic, 21.0% Asian/Pacific Islander (PI) and the remainder of other or unknown race/ethnicity (12.8%). Overall, 17.9% met criteria for obesity defined by BMI ≥95th percentile, with a greater proportion among boys versus girls, and slightly greater among younger versus older age group (Table 1). Differences were also seen by race/ethnicity. Among boys, the highest prevalence of obesity was seen in Hispanics (28.9%), followed by blacks (20.5%), Asians (17.6%) and whites (15.6%, p < 0.001 for all comparisons). Among girls, the highest prevalence was seen in blacks (23.3%) followed by Hispanics (21.5%), whites (12.1%) and Asians (9.2%, p <0.01 for all comparisons). Figure 1 further compares prevalence findings by race/ethnicity within each age-sex subgroup. Overall, 5.6% of the cohort had severe obesity defined by BMI ≥120% of the 95th BMI percentile, with a greater proportion among boys compared to girls (6.6% vs. 4.5%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of severe obesity also varied by race/ethnicity, ranging from 3.5% in Asians and 3.8% in whites to 8.3% in blacks and 8.5% in Hispanics (p <0.001 for Asians and whites vs. blacks and Hispanics). When examined across age-sex subgroups (Figure 1), the prevalence of severe obesity was highest in Hispanic boys aged 6–11 (9.7%) and 12–17 (10.6%) years and Black girls aged 12–17 (9.5%) years. In multivariable analyses, increasing age, male sex (adjusted odds ratio OR 1.5, 95% confidence interval CI 1.5-1.6), Hispanic ethnicity (OR 2.4, 95% CI 2.2-2.5) and black race (OR 2.3, 95% CI 2.1-2.5) were independent predictors of severe obesity.

The proportion of children and adolescents with moderate and severe obesity by age, sex and race/ethnicity. Comparisons by race/ethnicity within each age-sex group showed that the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile) was significantly different between all racial/ethnic subgroups (p < 0.01) except for differences in obesity prevalence for black vs Asian 6–11 year old boys (p = 0.90), black vs. Hispanic 6–11 year old girls (p = 0.64), and white vs. Asian 12–17 year old boys (p = 0.37). The prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile) was also significantly different between all racial/ethnic subgroups (p < 0.01), except for white vs. Asian (p = 0.06) and black vs. Hispanic 6–11 year old girls (p = 0.96), and white vs. Asian 12–17 year old boys (p = 0.58).

Table 2 shows the proportion of children within each BMI percentage category above the 95th percentile, by age and sex. For the 21,013 obese children (BMI ≥95th percentile), nearly one third were severely obese (BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile). Half of severely obese youth had BMI 120-129% of the 95th percentile and the remainder were evenly distributed across BMI 130-139% and BMI ≥140% of the 95th percentile. The remaining two thirds of obese children met criteria for moderate obesity (BMI 100-119% of the 95th percentile). For both boys and girls with BMI ≥95th percentile, a greater proportion of older compared to younger children met criteria for severe obesity (p < 0.05 comparing age 6–11 vs. 12–17 years old).

There was a strong tendency for obese children to remain in an obese BMI category over the follow-up period of this study. Follow-up analyses conducted using data from 80,697 children age 6–13 years old at the index visit and 2–3 years older at the time of subsequent BMI measurement (median 2.3 years, interquartile range 2.1-2.8 years after the index visit) demonstrated that 71.9% of children with severe obesity continued to be severely obese (with an even greater proportion among younger children) and an additional 24.7% remained obese but their BMI declined to the moderately obese range (Figure 2D). Among moderately obese children, 10.5% became severely obese (14.1% for children ages 6–7) while 57.1% remained moderately obese and 26.6% became overweight but not obese (Figure 2C). Less than one fifth (15.3%) of overweight children became moderately obese, while half (51.2%) remained overweight and one third (33.2%) had follow-up BMI in the normal range (Figure 2B).

Follow-up BMI category based on BMI percentile and BMI percentage of the 95thpercentile by age and BMI at the index visit. (A) For children with normal BMI at the index visit (N = 50,685), an increasing proportion of younger children were overweight at 2–3 years of follow-up (p < 0.001 comparing 6–7 and 8–9 year olds to 12–13 year olds, with no differences between 10–11 and 12–13 year olds, p = 0.6). (B) For children who were overweight at the index visit (N = 14,057), an increasing proportion of younger children were obese at follow-up (p <0.001, test for trend). (C) For children who were moderately obese at the index visit (BMI 100-119% of the 95th percentile, N = 9848), an increasing proportion of younger children were obese at follow-up (p <0.001, test for trend). The proportions of moderately obese children who remained obese at follow-up were significantly different between all age groups (p <0.01) except for 10–11 year olds compared to 12–13 year olds. (D) For children who were severely obese at the index visit (N = 4295), nearly all were obese or severely obese at follow-up (95.7-99.3%). Children in the youngest age group (6–7 years old) had the highest prevalence of severe obesity at follow-up compared to other age groups (p <0.05). Differences between the older age groups were not significantly different.

Among obese children, we also examined whether there was a graded relationship between increasing BMI percentage above the 95th percentile and elevated blood pressure. As shown in Table 3, the proportion of children with normal blood pressure fell while those with prehypertension or hypertension increased as BMI percentage increased above the 95th percentile. Adjusting for differences in age, sex and race/ethnicity, a significant graded relationship between obesity severity and hypertension remained, with the adjusted odds of hypertension increasing across increasing BMI strata: OR 1.5 (CI 0.9-2.3) for BMI 110-119%, OR 1.8 (CI 1.1-3.0) for BMI 120-129%, OR 3.5 (CI 2.1-5.8) for BMI 130-139%, and OR 5.7 (CI 3.6-8.9) for BMI ≥140% of the 95th BMI percentile, compared to BMI 100-109% of the 95th BMI percentile. Severe obesity (BMI ≥120% of the 95th BMI percentile) was associated with a 2.7-fold increased odds of hypertension compared to those with moderate obesity (BMI 100-119% of the 95th percentile; adjusted OR 2.7, CI 2.0-3.7). These results were similar when restricting analyses to the subset of 11,705 obese children and adolescents who had three consecutive BP measurements (data not shown).

Discussion

This study extends results from previously published studies of pediatric obesity by examining gradations in severe obesity by gender, age and race/ethnicity. In addition, we evaluated the persistence of obesity and obesity severity over 2–3 years, as well as the association between obesity severity and hypertension. Severe obesity was found in 5.6% of children and adolescents age 6–17 years old, with prevalence highest among children of Hispanic ethnicity or black race, similar to findings for overall obesity (BMI ≥95th percentile). National data[7] and other racially and ethnically diverse cohorts[12] also demonstrate a disproportionately higher prevalence of severe obesity in Hispanic boys and non-Hispanic black girls. Furthermore, longitudinal data on BMI tracking from more than 80,000 children and adolescents included within this study cohort (of whom 9848 were moderately obese and 4295 severely obese at the index visit) demonstrate that severely obese children tend to maintain the same degree of obesity over time, particularly when evident at a young age. These findings support data from other longitudinal pediatric cohorts documenting a strong tracking effect of elevated BMI in childhood, as well as into adulthood[18–23]. Similar shifts in BMI across normal, overweight, obese and severely obese categories were also observed in a multisite school-based study of 3993 U.S. sixth graders re-examined later in eigth grade, where 76% of severely obese youths (alternatively defined by the 99th BMI percentile) remained severely obese after 2.5 years of follow-up[24].

While previous findings from this source cohort demonstrated that pediatric obesity was significantly related to an increased prevalence of hypertension[13], in this study we applied new obesity stratification criteria and found that the risk of hypertension increased as the degree of obesity increased, with a nearly three-fold greater risk of hypertension among severely obese children compared to moderately obese children. These findings are consistent with the known interrelationship of adiposity, hypertension and cardiometabolic factors in children[5, 25–29], supporting evidence of greater risk with extreme or severe obesity[5, 30–32], and further quantify the association between obesity severity and hypertension as a representation of cardiovascular health risk. The persistence of severe obesity in longitudinal analyses, supporting data from other pediatric studies examining longitudinal shifts in BMI category among smaller population cohorts[24], also documents an ongoing highly significant adverse cardiovascular impact and emphasizes the need for early weight loss management.

These data have several clinical and public health implications. First, consistent with recently published concensus statements emphasizing the importance of identifying and tracking severe obesity in children and adolescents[10], current approaches to classifying obesity in the clinical setting should be refined at the higher end of the BMI spectrum to more precisely identify those with severe obesity. Categorization based strictly on BMI percentiles does not adequately stratify risk within the extreme BMI range (>99th percentile). In addition, conventional growth charts have a BMI limit of 36–37 kg/m2, which is problematic for tracking of weight status in adolescents with extremely high BMI[11]. In this study, we found that classifying obesity severity based on BMI percentage of the 95th percentile, as previously proposed by others[9, 11], has the advantage of more precisely categorizing extremely obese individuals for both clinical tracking and research purposes. More importantly, our data demonstrate that this new obesity classification system results in clinically relevant thresholds of higher order obesity associated with graded health risk, as defined by hypertension.

Several factors may constrain the interpretation of our data. First, these data were limited to a subset of children receiving well-child care in a northern California healthcare delivery system and thus may not be fully representative of other population demographics or regions. Second, there is the theoretical possibility that growth chart reference data may differ by age, with implications for examining longitudinal trends. However, our BMI thresholds focus on well-established reference data for the 85th and 95th BMI percentiles thresholds, deriving higher order obesity based on the 95th percentile rather than the 97th or 99th BMI percentiles. Third, while we believe the measurements of BP in these subjects were accurate, assessment of BP in extremely obese children is a challenge due to limitations in cuff size[26, 33, 34]. Finally, we limited our cardiovascular risk assessment to blood pressure, since lipid measurements were not uniformly available to further estimate cardiovascular risk in addition to blood pressure. As such, we believe that the previously documented tracking effect for blood pressure in this age range to adulthood[17] supports the use of hypertension as an important component of overall cardiovascular risk.

In summary, among the substantial number of children with obesity (BMI at or above the 95th percentile), identifying subsets of those with more extreme obesity is of clinical importance. Stratification of obesity by percentage above the 95th BMI percentile shows a graded increased risk of hypertension and may be related to increased risk of other cardiovascular risk factors such as dyslipidemia and prediabetes. A more refined and precise classification of severe pediatric obesity using contemporary criteria[10] may serve to improve clinical practice, tracking, as well as public health surveillance, and facilitate research on the best approaches to managing cardiovascular risk in these subgroups of varying obesity severity.

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD: Prevalence of Obesity Among Children and Adolescents: United States, Trends 1963–1965 Through 2007–2008. 2010, National Center for Health Statistics E-Stat, Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_child_07_08.pdf

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM: Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012, 307: 483-490. 10.1001/jama.2012.40.

Ogden CL, Flegal KM: Changes in terminology for childhood overweight and obesity. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010, 25: 1-5.

Barlow SE: Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007, 120 (Suppl 4): S164-S192.

Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH: Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007, 150: 12-17. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. e12

Skelton JA, Cook SR, Auinger P, Klein JD, Barlow SE: Prevalence and trends of severe obesity among US children and adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2009, 9: 322-329. 10.1016/j.acap.2009.04.005.

Wang YC, Gortmaker SL, Taveras EM: Trends and racial/ethnic disparities in severe obesity among US children and adolescents, 1976–2006. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011, 6: 12-20.

Woo JG: Using body mass index Z-score among severely obese adolescents: a cautionary note. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009, 4: 405-410. 10.3109/17477160902957133.

Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR: Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 centers for disease control and prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 90: 1314-1320. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335.

Kelly AS, Barlow SE, Rao G, Inge TH, Hayman LL, Steinberger J, Urbina EM, Ewing LJ, Daniels SR: Severe obesity in children and adolescents: identification, associated health risks, and treatment approaches: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2013, 128: 1689-1712. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a5cfb3.

Gulati AK, Kaplan DW, Daniels SR: Clinical tracking of severely obese children: a new growth chart. Pediatrics. 2012, 130: 1136-1140. 10.1542/peds.2012-0596.

Koebnick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, Getahun D, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, Porter AH, Der-Sarkissian JK, Jacobsen SJ: Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010, 157: 26-31. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.025. e22

Lo JC, Sinaiko A, Chandra M, Daley MF, Greenspan LC, Parker ED, Kharbanda EO, Margolis KL, Adams K, Prineas R, Magid D, O'Connor PJ: Prehypertension and hypertension in community-based pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2013, 131: e415-e424. 10.1542/peds.2012-1292.

A SAS Program for the 2000 CDC Growth Charts (ages 0 to < 20 y). [http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm]

Lo JC, Maring B, Chandra M, Daniels SR, Sinaiko A, Daley MF, Sherwood NE, Kharbanda EO, Parker ED, Adams KF, Prineas RJ, Magid DJ, O'Connor PJ, Greenspan LC: Prevalence of obesity and extreme obesity in children aged 3–5 years. Pediatric Obesity. 2013

Cut-offs to define outliers in the 2000 CDC Growth Charts. [http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/resources/BIV-cutoffs.pdf]

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004, 114: 555-576.

Biro FM, Huang B, Morrison JA, Horn PS, Daniels SR: Body mass index and waist-to-height changes during teen years in girls are influenced by childhood body mass index. J Adolesc Health. 2010, 46: 245-250. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.023.

Thompson DR, Obarzanek E, Franko DL, Barton BA, Morrison J, Biro FM, Daniels SR, Striegel-Moore RH: Childhood overweight and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. J Pediatr. 2007, 150: 18-25. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.09.039.

Kvaavik E, Tell GS, Klepp KI: Predictors and tracking of body mass index from adolescence into adulthood: follow-up of 18 to 20 years in the Oslo Youth Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003, 157: 1212-1218. 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1212.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH: Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997, 337: 869-873. 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301.

Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF: Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 76: 653-658.

Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Daniels SR, Wang P: Race, childhood insulin, childhood caloric intake, and class 3 obesity at age 24: 14-year prospective study of schoolgirls. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012, 20: 597-604. 10.1038/oby.2011.126.

Marcus MD, Foster GD, El Ghormli L, Baranowski T, Goldberg L, Jago R, Linder B, Steckler A, Trevino R: Shifts in BMI category and associated cardiometabolic risk: prospective results from HEALTHY study. Pediatrics. 2012, 129: e983-e991. 10.1542/peds.2011-2696.

Charakida M, Jones A, Falaschetti E, Khan T, Finer N, Sattar N, Hingorani A, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Deanfield JE: Childhood obesity and vascular phenotypes: a population study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012, 60: 2643-2650. 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.1017.

Sorof J, Daniels S: Obesity hypertension in children: a problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002, 40: 441-447. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000032940.33466.12.

Sorof JM, Poffenbarger T, Franco K, Bernard L, Portman RJ: Isolated systolic hypertension, obesity, and hyperkinetic hemodynamic states in children. J Pediatr. 2002, 140: 660-666. 10.1067/mpd.2002.125228.

Flynn J: The changing face of pediatric hypertension in the era of the childhood obesity epidemic. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013, 28: 1059-1066. 10.1007/s00467-012-2344-0.

Tu W, Eckert GJ, DiMeglio LA, Yu Z, Jung J, Pratt JH: Intensified effect of adiposity on blood pressure in overweight and obese children. Hypertension. 2011, 58: 818-824. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.175695.

Ice CL, Murphy E, Cottrell L, Neal WA: Morbidly obese diagnosis as an indicator of cardiovascular disease risk in children: results from the CARDIAC Project. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011, 6: 113-119. 10.3109/17477161003792556.

Valerio G, Maffeis C, Balsamo A, Del Giudice EM, Brufani C, Grugni G, Licenziati MR, Brambilla P, Manco M: Severe obesity and cardiometabolic risk in children: comparison from two international classification systems. PloS One. 2013, 8: e83793-10.1371/journal.pone.0083793.

Marcus MD, Baranowski T, DeBar LL, Edelstein S, Kaufman FR, Schneider M, Siega-Riz AM, Staten MA, Virus A, Yin Z: Severe obesity and selected risk factors in a sixth grade multiracial cohort: the HEALTHY study. J Adolesc Health. 2010, 47: 604-607. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.017.

Gomez-Marin O, Prineas RJ, Rastam L: Cuff bladder width and blood pressure measurement in children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 1992, 10: 1235-1241. 10.1097/00004872-199210000-00018.

Whincup PH, Cook DG, Shaper AG: Blood pressure measurement in children: the importance of cuff bladder size. J Hypertens. 1989, 7: 845-850. 10.1097/00004872-198910000-00010.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joel Gonzalez, Jena Joy MD and Gabriela Sanchez for assistance with literature review and manuscript preparation. This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health 1RO1HL093345 to HealthPartners Research Foundation (Patrick O’Connor, Principal Investigator) and conducted within the Cardiovascular Research Network, a consortium of research organizations affiliated with the HMO Research Network and sponsored by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (U19 HL91179-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JL, SD, AS and LG conceptualized and designed the study. MC conducted the data analyses. JL, LG, BM, AS and RP drafted the initial manuscript. All authors (JL, MC, AS, SD, RP, BM, EP, NS, MD, EK, KA, DM, PO, LG) provided critical input on data analysis and interpretation, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, J.C., Chandra, M., Sinaiko, A. et al. Severe obesity in children: prevalence, persistence and relation to hypertension. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2014, 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2014-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2014-3