Abstract

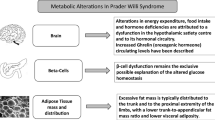

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic disorder, caused by lack of expression of genes on the paternally inherited chromosome 15q11.2-q13. In infancy it is characterized by hypotonia with poor suck resulting in failure to thrive. As the child ages, other manifestations such as developmental delay, cognitive disability, and behavior problems become evident. Hypothalamic dysfunction has been implicated in many manifestations of this syndrome including hyperphagia, temperature instability, high pain threshold, sleep disordered breathing, and multiple endocrine abnormalities. These include growth hormone deficiency, central adrenal insufficiency, hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and complications of obesity such as type 2 diabetes mellitus. This review summarizes the recent literature investigating optimal screening and treatment of endocrine abnormalities associated with PWS, and provides an update on nutrition and food-related behavioral intervention. The standard of care regarding growth hormone therapy and surveillance for potential side effects, the potential for central adrenal insufficiency, evaluation for and treatment of hypogonadism in males and females, and the prevalence and screening recommendations for hypothyroidism and diabetes are covered in detail. PWS is a genetic syndrome in which early diagnosis and careful attention to detail regarding all the potential endocrine and behavioral manifestations can lead to a significant improvement in health and developmental outcomes. Thus, the important role of the provider caring for the child with PWS cannot be overstated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a genetic disorder, with a prevalence of 1/10,000-1/30,000, resulting from lack of expression of genes on the paternally inherited chromosome 15q11.2-q13. DNA methylation analysis within the Prader-Willi critical region detects the condition >99% of the time and is the first-line genetic test [1]. Further testing is required to determine the genetic subtype. Deletion of the paternally inherited 15q11.2-q13 region accounts for 70% of cases and can be determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) or microarray. Maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) of chromosome 15 accounts for 25% of cases and can be determined by DNA polymorphism analysis in the affected individual and both parents. Imprinting defects account for most of the remaining 5% [2].

Major clinical manifestations of PWS include hypotonia with weak suck and poor feeding in infancy leading to failure-to-thrive, with later development of hyperphagia. Other clinical features include developmental delay, cognitive disability, and behavior problems, specifically stubbornness, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and skin picking. Many of the clinical manifestations can be explained by hypothalamic dysfunction, including hyperphagia, temperature instability, high pain threshold, and sleep disordered breathing. The hypothalamic dysfunction also gives rise to variable pituitary hormone insufficiencies.

With improved recognition and availability of testing methodologies, PWS is being diagnosed earlier, often in the first few months of life. Earlier diagnosis, allowing for earlier access to developmental resources, recombinant human growth hormone (hGH) therapy, and anticipatory guidance, has significantly improved the long-term health and developmental outcomes of children with PWS [3]. Several excellent clinical guidelines have been published on the comprehensive management of PWS [3–5]. In this review, we focus on current evidence regarding the endocrine manifestations and their management with the goal of optimizing long-term outcomes for children and adolescents with PWS.

Review

Appetite and nutritional management

The transition from poor feeding and failure-to-thrive to hyperphagia is complex with 7 nutritional phases characterized by Miller et al. [6] (Table 1). Eating behavior and functional MRI studies have identified decreased satiety and increased reward response to food, in contrast to increased hunger, as major factors contributing to the hyperphagia [7–11]. The orexogenic hormone ghrelin is very high in individuals with PWS, even before the hyperphagia occurs [12, 13]. However, decreasing ghrelin levels in these subjects with somatostatin or long-acting octreotide does not have an effect on appetite [14, 15]. Lean body mass (LBM) is also decreased, resulting in decreased total and resting energy expenditure (REE), further promoting weight gain. [16].

A strictly controlled diet and food security, both physical and psychological, are critical in the management of PWS. When children with PWS feel secure around food, their overall stress and anxiety are reduced and behavior is improved. Physical food security consists of locking up food and other physical barriers to food access. Principles of psychological food security include “No Doubt, No Hope (No Chance), and No Disappointment”. There is “no doubt” that the next meal is coming, nor how much and what type of food will be provided. The meal plan is known ahead of time and a structured routine is followed that focuses on the flow of activities rather than specific times. There is “no hope (no chance)” of food acquisition outside of what is provided, and there is “no disappointment” as what is promised is followed through and there are no false expectations [17].

Early dietary intervention and long-term nutrition monitoring lead to better outcomes. In one study, use of a controlled prescribed diet, starting at a median age of 14 months, resulted in normal body mass index (BMI) at age 10 in all subjects. The diet consisted of 10 kcal/cm length per day with a healthy balance of macronutrients. Interestingly, parents rarely reported that their children experienced hyperphagia or food cravings, suggesting a learned behavioral component of the hyperphagia [18]. A diet with carbohydrate content as low as 45% of total calories may have more favorable effects on body composition and fat utilization [19]. Prescribed daily physical activity is also important and contributes to improved body composition and REE [20].

Growth hormone

The reported prevalence of growth hormone (GH) deficiency in PWS ranges from 40-100% depending on the diagnostic criteria used, with most studies reporting a prevalence in the higher end of this range [21, 22]. Clinical manifestations consistent with GH insufficiency include short stature despite obesity, abnormal body composition, low insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels, and decreased GH secretion on provocative testing [23]. Even infants and toddlers, despite an often normal BMI, have increased fat mass and decreased LBM compared to normal children of the same age [24, 25]. Recombinant human growth hormone (hGH) was FDA-approved in the United States in 2000 for the indication of “growth failure due to Prader-Willi syndrome.” In Europe, “improvement of body composition” is included in the approved indication of hGH therapy in PWS. In practice, hGH is primarily used for benefits other than increased height, including improved body composition and motor function. A consensus guideline on hGH therapy in PWS was recently published [23].

The longest term controlled study of hGH in PWS compared a cohort of children aged 6–9 years who had been treated with hGH for 6 years, starting at age 4–20 months, to a cohort of age and gender-matched children who had not been treated [26]. The treated group had significantly lower body fat percentage (36% versus 45%), greater muscle mass, more favorable lipid profiles, and better motor strength and function. Randomized controlled trials of hGH therapy from 12 to 30 months duration in infants as young as 4 months, toddlers, and older children have also shown significant improvements in body composition and height, with the greatest magnitude of change seen in the first year of therapy [27–33]. Improvements have also been reported in fat utilization, inspiratory muscle forces, motor function, hand and foot size, and lipid profiles in studies up to 4 years duration [27, 34, 35]. Cumulative hGH dosage over 10 years has correlated inversely with total body fat percentage [36].

Randomized controlled trials of hGH therapy for 1 and 2 years duration have also shown benefits on development and cognition. In one study, patients started on hGH prior to age 18 months had a significant increase in mobility scores on developmental testing [30]. Significant improvement in cognitive and motor development on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II has been reported with hGH therapy, with those infants having the lower baseline motor skills showing the greatest improvement [31]. In another study, infants and toddlers progressed significantly more in language and cognitive development as assessed by the Capute scales [32]. In a 2 year randomized controlled trial of hGH in prepubertal children, intelligent quotient (IQ) standard deviation score (SDS) decreased in the non-treated group and remained stable in the treated group. IQ SDS then increased over 4 years when all individuals in the study were treated [37]. Proposed mechanisms for these observed improvements in cognition include positive effects of hGH on brain development, suggested by an association with head circumference growth, and an increased ability to interact with the learning environment due to improved motor function [31, 32, 37]. The effect size of these reported improvements however are relatively small so larger long-term studies are needed to further investigate this area.

One study investigating the effect of hGH on behavior in PWS showed improvement in depressive symptoms with the greatest improvement in those over 11 years old [38]. No deterioration in other aspects of behavior was found with hGH in this study, consistent with findings of other studies [39]. Furthermore, hGH had no effect on bone density after 2 years of treatment in prepubertal children and in adults with PWS [40, 41].

The optimal age to start hGH is not known, but expert consensus is to start prior to the onset of obesity, which often occurs by age 2 [23]. Some experts recommend treating as early as 3 months of age[23]. Clinical guidelines recommend a starting dose of 0.5 mg/m2/day with progressive increase to 1 mg/m2/day [4, 5, 23]. A randomized controlled trial of hGH dosing showed that a dose of at least 1 mg/m2/day is required for positive effects on body composition [42]. Furthermore, most of the studies detailed above showing benefits of hGH used a dosage of 1 mg/m2/day.

The benefits of hGH therapy in childhood may persist into adulthood even after the hGH is discontinued. In one study, adults (mean age 25.4 years) who were treated with hGH during childhood had improved body composition and metabolic status compared to those who were not treated. The treated group had a lower mean BMI (32.4 versus 41.2), a greater percentage with BMI <30 (45% versus 18.2%), lower mean hemoglobin A1c, lower mean insulin resistance index, and less hypertension. The treated group had been diagnosed at a younger age (4.8 versus 10.1 years) so other aspects of the earlier diagnosis may have contributed to the improved outcomes [43].

The role of hGH therapy in adults with PWS is less clearly defined. Recent studies have begun to illuminate the risk benefit ratio of hGH treatment in this patient population. The prevalence of GH deficiency in adults with PWS ranges from 15% to 95%, depending on the agents used for stimulation testing and the threshold GH level used to define deficiency [44, 45]. The average reported prevalence of severe GH deficiency is 40-50% [46]. Those with the deletion subtype have higher stimulated GH responses than those with the UPD subtype [47]. Beneficial effects of hGH therapy in adults with PWS when administered for 6 months to several years include decreased fat mass, increase in LBM, and improved respiratory muscle function [44–46]. In several studies, edema was reported after initiation of hGH, but not to a degree that led to cessation of therapy [46]. Evidence is conflicting on the degree that hGH therapy affects fasting glucose, fasting insulin and homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) index but close monitoring of glucose homeostasis in treated patients is warranted [44–46]. Many regulatory agencies require dynamic testing to diagnose GH deficiency prior to treating adults with PWS [23]. However, there is currently no consensus on the need for such testing after the attainment of adult height as those who do not test GH deficient may also benefit from hGH therapy. Further investigation is needed in this area. Recent expert consensus recommends a starting dose of 0.1-0.2 mg/day in adults with maintenance of IGF-1 levels between 0 and + 2 SDS to achieve beneficial effects of hGH with the lowest possible risk for adverse events [23].

HGH therapy in PWS is not without risk and needs to be undertaken thoughtfully. Contraindications according to the pharmaceutical companies and expert consensus include severe obesity, untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), uncontrolled diabetes, active malignancy, and active psychosis [23]. Concerns have been raised regarding the association of hGH with excessive elevations in IGF-1, sleep disordered breathing, scoliosis, alterations in glucose metabolism, and sudden death. There is an increasingly recognized phenomenon of high IGF-1 levels despite relatively low hGH doses that seems to be unique to PWS. Potential concerns related to excessively high IGF-1 levels include lymphoid hyperplasia leading to OSA and a theoretical increase in malignancy risk. In a study of 55 children with PWS treated with GH for 4 years, IGF-1 levels increased significantly in the first year of therapy and decreased slightly at year 4 (mean SDS +2.1). Three subjects had IGF-1 levels >3.5 SDS that declined to 2–3 SDS after GH dose reduction [35]. In one study, IGF-1 and IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) levels were evaluated over a 2 year period in a group of 33 children with PWS treated with hGH. These subjects were compared to 591 subjects treated for GH deficiency. The PWS group had significantly higher IGF-1 levels despite lower doses of hGH. However, there was no significant difference in IGF-1 to IGFBP3 molar ratios between groups, suggesting that bioavailable IGF-1, and therefore risk for adverse effects, may be similar in both groups [48]. The optimal management of these high IGF-1 levels is currently unclear. The potential risk needs to be balanced against the evidence that at least 1 mg/m2/day is required for favorable effects on body composition. Current recommendations are to monitor IGF-1 levels at least every 6 to 12 months and attempt titrate the hGH dosage to maintain levels between +1 and +2 SDS [23].

Patients with PWS have a high incidence of both central and obstructive sleep apnea [49–51]. Factors contributing to the sleep disordered breathing include obesity, restrictive lung disease due to muscle weakness or scoliosis, reduced ventilatory response to hypercapnia, and hypoxia during sleep and wakefulness [52]. HGH therapy potentially worsens sleep disordered breathing because increased IGF-1 levels lead to lymphoid hyperplasia [53, 54]. One study showed decreased central sleep apnea in patients treated with hGH, but worsening of OSA that correlated with elevated IGF-1 levels [53]. In other studies, hGH therapy was also associated with beneficial effects on central aspects of sleep disordered breathing, as well as inspiratory and expiratory muscular strength [34, 39].

Current guidelines recommend the following evaluation of sleep disordered breathing prior to starting hGH: 1). Otolaryngology (ENT) referral if there is a history of sleep disordered breathing, snoring, or if enlarged tonsils and adenoids are present, with consideration of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. 2). Referral to a pulmonologist or sleep clinic. 3). Sleep oximetry in all patients, preferably by polysomnographic evaluation. Significant OSA should be treated prior to starting hGH. Repeat polysomnography is recommended within the first 3–6 months of starting hGH [23].

Due in part to the underlying hypotonia, scoliosis affects 30-80% of patients with PWS [55]. Multiple studies, including randomized controlled trials, have shown no effect of hGH therapy on scoliosis, even in patients started on hGH at younger ages [26, 27, 56–58]. Scoliosis is not considered a contraindication for initiating or continuing hGH therapy in patients with PWS. However, prior to initiating therapy, a spine film with orthopedic referral if necessary is recommended. Once hGH therapy is initiated, a spine film and/or orthopedic assessment should be considered if there is concern about scoliosis progression [23].

Alteration in glucose metabolism is another side effect to consider in patients with PWS receiving hGH. HGH can lead to increased insulin resistance due to its counter-regulatory effects on insulin action. Pediatric studies show no significant alterations in glucose homeostasis with hGH therapy for up to 4 years [26, 27, 35]. Adult studies show a minor increase in fasting glucose and a trend toward increased fasting insulin and HOMA, but no change in hemoglobin A1c [46]. Recent expert consensus recommends surveillance of hemoglobin A1c, fasting glucose, and fasting insulin for those receiving hGH therapy and consideration of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for those who are obese, and/or >12 years old, and/or have a family history of diabetes [23].

The association of hGH therapy with sudden death in PWS has received significant attention. Between 2002 and 2006, 20 deaths were reported in children with PWS treated with hGH, but evidence has not been convincing that there is a causative relationship between sudden death and hGH therapy [59]. In a review of 64 cases of death in children with PWS ranging in age from a few days of life to 19 years, 28 subjects (44%) were receiving hGH therapy at the time of death. Respiratory disorders were the most common cause of death, and there were no differences in cause of death between the hGH treated and untreated group. However, 75% of the deaths in the hGH treated group occurred within 9 months of hGH therapy initiation, a finding that suggests a need for close surveillance for any exacerbation of sleep related breathing disorders during the first year of hGH therapy [60]. Sudden death and the possible association with hGH therapy may be related to the increased risk for central adrenal insufficiency (see below), especially in the setting of an acute respiratory illness [60].

Adrenal insufficiency

Central adrenal insufficiency occurs in PWS but the frequency is unclear. Children and adults with PWS are at risk for adrenal insufficiency due to the generalized hypothalamic dysfunction. In a case series of unexpected death in PWS, autopsies performed in 3 out of 4 young children who presented with febrile or other acute illnesses revealed small adrenal glands by weight criteria. The 4th child’s adrenal weight was below average [61]. Also reported is an adolescent male with PWS who developed symptomatic adrenal insufficiency during spine surgery that resolved promptly after administration of glucocorticoid [62]. None of these patients were reported to have been on hGH. GH inhibits 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11βHSD-1), resulting in less cortisone conversion to active cortisol. Thus hGH may further blunt the stress response to an acute illness when the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is already not functioning optimally. The first published cross-sectional analysis (n = 25) of adrenal insufficiency in children with PWS found that 60% tested insufficient by overnight single-dose metyrapone testing. Baseline hormone levels were not different in those who tested sufficient versus insufficient suggesting that there is a deficit in the reserve necessary for the stress response [63]. Subsequent studies using different testing methodologies, including low-dose and high-dose Synacthen and the insulin tolerance test, did not show the same frequency of adrenal insufficiency with the highest percentages at 14-15% [64–68]. These studies are summarized in Table 2. The true prevalence of central adrenal insufficiency in PWS remains unclear and is an area in need of further investigation.

As a result, no consensus exists on the appropriate evaluation and management of central adrenal insufficiency in PWS. Obtaining cortisol and ACTH levels during an acute illness or other stressful situation may provide useful diagnostic information. One group recommends considering stress-dose steroids for all patients with PWS during stress, to include mild upper respiratory infections, since patients with PWS often do not show significant signs of illness such as fever or vomiting [63]. Another group recommends considering prophylactic stress dose steroids for major surgery or at least having them readily available to administer for symptoms of adrenal insufficiency [62]. In our practice, we discuss with all families the possibility of adrenal insufficiency during stress and provide our patients with stress doses of hydrocortisone to store at home for administration during significant illness. We also recommend peri-operative stress dose steroids.

Hypogonadism

Hypogonadism is a consistent feature of both males and females with PWS. Clinical presentation includes genital hypoplasia, delayed or incomplete puberty, and infertility in the vast majority. Genital hypoplasia is evident at birth. In females it manifests as clitoral and labia minora hypoplasia and can easily be overlooked on physical examination. Males commonly have cryptorchidism, a poorly rugated, under pigmented, hypo plastic scrotum, and may have a small penis. Unilateral or bilateral cryptorchidism is present in 80-90% of males [2]. One author recommends considering a trial of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) to promote testicular descent for potential avoidance of surgical correction and general anesthesia given the risk for respiratory complications. HCG may also increase scrotal size and penile length, which can improve orchidopexy outcomes and facilitate later standing micturition [3]. However, there are no published data regarding the efficacy of this practice in patients with PWS. Surgical correction of cryptorchidism should be completed in the first or second year of life [3, 4].

Hypogonadism was classically thought to be hypothalamic in etiology, similar to many other manifestations of PWS. However, recent evidence has emerged supporting primary gonadal failure as a significant contributor to male hypogonadism [69–71]. A recent longitudinal study of gonadal function in 68 males with PWS ages 6 months to 16 years showed that inhibin B levels were normal in the prepubertal period, but decreased significantly with a concordant rise in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) after puberty onset. Testosterone levels increased during puberty but remained below the 5th percentile, while luteinizing hormone (LH) levels increased but not above the 95% [70]. Other studies have also shown a combined picture of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with relatively low LH levels, and primary hypogonadism with low inhibin B and relatively high FSH levels [71, 72]. Gonadal function has also been evaluated longitudinally in 61 girls with PWS. The primordial follicle pool and the number of small antral follicles were conserved. However, maturation of follicles and progression of pubertal development were impaired. LH levels were relatively low for the low estradiol levels observed, and FSH levels were normal. Pubertal onset was similar in timing to the normal population, but progression was delayed [73].

Although most patients with PWS present with delayed and/or incomplete puberty, other pubertal variations have been reported. Precocious adrenarche occurs in 15-30% of patients and is felt to be secondary to obesity or possibly increased adrenal exposure to insulin or IGF-1 [74]. Precocious puberty has been reported in 4% of both boys and girls [74–76]. Treatment of precocious puberty with gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs is not indicated as pubertal advancement is not sustained [4].

Many patients with PWS require hormonal treatment for induction, promotion or maintenance of puberty. Benefits of sex steroid replacement include positive effects on bone health, muscle mass, and possibly general well-being. No consensus exists as to the most appropriate regimen for pubertal induction or promotion but experts agree that the dosing and timing should reflect as closely as possible the process of normal puberty [4]. Available data suggest that sex steroid deficiency contributes to low bone density in adults with PWS [77, 78]. Therefore, in females, sex hormone replacement should be considered if there is amenorrhea/oligomenorrhea or low bone mineral density (BMD) in the presence of reduced estradiol levels [77]. Testosterone administration should be considered in males with PWS as for any other hypogonadal patient. Androgen therapy can be more physiologically administered using testosterone patches and gel preparations. These delivery systems avoid the peaks and troughs of injections, which may be of particular importance in PWS because of historical concerns about aggressive behaviors with testosterone treatment [4]. However, patients may have difficulty with topical treatment due to skin irritation and skin picking behaviors.

No cases of paternity have been reported in PWS, but 4 pregnancies have been documented in females with PWS. These 4 reported pregnancies resulted in 2 normal offspring and 2 offspring with Angelman Syndrome [79, 80] (unpublished abstract, Cassidy SB and Vats D, 25th annual Prader-Willi Syndrome Association scientific meeting in Orlando, FL Nov 2011). The potential for fertility in females with PWS necessitates discussion of sexuality and birth control at an appropriate age.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism has been reported in approximately 20-30% of children with PWS [22, 81]. Similar to other endocrinopathies in PWS, the etiology is thought to be central in origin. A recent study of children with PWS under 2 years of age revealed that 72.2% had abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis evidenced by low total or free thyroxine (FT4 ) in the presence of normal thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) [82]. Studies of adult patients with PWS show that the frequency of thyroid disease is 2%, which is similar to that of the general population [83]. In a study of thyroid function in 75 children with PWS treated with hGH therapy at 1 mg/m2/day for 1 year, FT4 levels dropped significantly, while triiodothyronine (T3) levels did not change, consistent with increased GH-promoted peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 [84]. Studies investigating the natural history of hypothyroidism in patients with PWS, as well as the effects of thyroid hormone treatment, are needed. We recommend that FT4 and TSH be screened in the first 3 months of life and annually thereafter, especially if the patient is receiving hGH therapy, with initiation of levothyroxine if hypothyroxinemia is discovered.

Glucose metabolism and diabetes

Type 2 diabetes mellitus has been reported in 25% of adults with PWS with onset at a mean age of 20 years. The mean BMI of those who developed type 2 diabetes in this cohort was 37 kg/m2[85]. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance are much less frequent in children with PWS. A study of 74 children with PWS at a median age of 10.2 years showed that none had type 2 diabetes and only 4% had impaired glucose tolerance by OGTT [22]. Several studies have demonstrated that subjects with PWS, not receiving hGH therapy, had lower insulin levels and greater insulin sensitivity compared to controls matched for degree of obesity [86, 87]. Proposed reasons for the increased insulin sensitivity in PWS include relative diffuse as opposed to visceral obesity, lower GH levels, and higher ghrelin levels for the degree of obesity [88, 89]. Periodic surveillance for diabetes and features of the metabolic syndrome should be undertaken in obese individuals as is recommended for obesity in the general population. Similarly, evaluation of diabetes risk is recommended prior to initiation of hGH in obese patients over 12 years of age, with periodic surveillance for those on hGH treatment [23].

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and comprehensive care of patients with PWS have improved outcomes. Table 3 summarizes the screening and management of the endocrine manifestations of PWS. Areas where further research is needed include the etiology and management of hyperphagia, risks and management of high IGF-1 levels associated with relatively low hGH doses, optimal surveillance of sleep disordered breathing, further elucidation of the effect of hGH on cognition, the impact of hGH therapy in adulthood, frequency and management of adrenal insufficiency, and the frequency and natural history of hypothyroidism.

Resources for families and providers can be found through the Prader-Willi syndrome Association USA (http://www.pwsausa.org), the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (http://fpwr.org), and the International Prader-Willi syndrome Organization (http://www.ipwso.org).

Authors’ information

JE is faculty in the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Bethesda and is a CDR in the US Navy. She has a special interest in childhood and adolescent obesity. KV is Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Bethesda and is a LTC in the US Army. She has a 3 year-old son with Prader-Willi syndrome and is active in the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association USA and the Foundation for Prader-Willi Research.

Abbreviations

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- 11βHSD-1:

-

11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ENT:

-

Ears, nose, and throat

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- FT4:

-

Free thyroxine

- GH:

-

Growth hormone

- GnRH:

-

Gonadotropin releasing hormone

- hCG:

-

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- hGH:

-

Human growth hormone

- HOMA:

-

Homeostatic model assessment

- IGF-1:

-

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- IGFBP3:

-

Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3

- IQ:

-

Intelligence quotient

- LBM:

-

Lean body mass

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OGTT:

-

Oral glucose tolerance test

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- PWS:

-

PRADER-Willi syndrome

- REE:

-

Resting energy expenditure

- SDS:

-

Standard deviation score

- T3:

-

Triiodothyronine

- TSH:

-

Thyroid stimulating hormone

- UPD:

-

Uniparental disomy.

References

Driscoll DJMJ, Schwartz S: Prader-Willi syndrome. GeneReviews™ [Internet]. Edited by: Pagon RAAM, Bird TD. 2012, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle

Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ: Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med. 2012, 14 (1): 10-26. 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0.

McCandless SE: Clinical report-health supervision for children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatr. 2011, 127 (1): 195-204.

Goldstone AP, Holland AJ, Hauffa BP, Hokken-Koelega AC, Tauber M: Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, 93 (11): 4183-4197. 10.1210/jc.2008-0649.

Miller JL: Approach to the child with prader-willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012, 97 (11): 3837-3844. 10.1210/jc.2012-2543.

Miller JL, Lynn CH, Driscoll DC, Goldstone AP, Gold JA, Kimonis V, Dykens E, Butler MG, Shuster JJ, Driscoll DJ: Nutritional phases in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2011, 155A (5): 1040-1049.

Lindgren AC, Barkeling B, Hagg A, Ritzen EM, Marcus C, Rossner S: Eating behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome, normal weight, and obese control groups. J Pediatr. 2000, 137 (1): 50-55. 10.1067/mpd.2000.106563.

Holland AJ, Treasure J, Coskeran P, Dallow J: Characteristics of the eating disorder in Prader-Willi syndrome: implications for treatment. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1995, 39 (5): 373-381. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1995.tb00541.x.

Holsen LM, Zarcone JR, Brooks WM, Butler MG, Thompson TI, Ahluwalia JS, Nollen NL, Savage CR: Neural mechanisms underlying hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2006, 14 (6): 1028-1037. 10.1038/oby.2006.118.

Shapira NA, Lessig MC, He AG, James GA, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y: Satiety dysfunction in Prader-Willi syndrome demonstrated by fMRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005, 76 (2): 260-262. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.039024.

Miller JL, James GA, Goldstone AP, Couch JA, He G, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y: Enhanced activation of reward mediating prefrontal regions in response to food stimuli in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007, 78 (6): 615-619. 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099044.

Haqq AM: Serum Ghrelin levels are inversely correlated with body mass index, age, and insulin concentrations in normal children and are markedly increased in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol & Metab. 2003, 88 (1): 174-178. 10.1210/jc.2002-021052.

Feigerlova E, Diene G, Conte-Auriol F, Molinas C, Gennero I, Salles JP, Arnaud C, Tauber M: Hyperghrelinemia precedes obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008, 93 (7): 2800-2805. 10.1210/jc.2007-2138.

Tan TM, Vanderpump M, Khoo B, Patterson M, Ghatei MA, Goldstone AP: Somatostatin infusion lowers plasma ghrelin without reducing appetite in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004, 89 (8): 4162-4165. 10.1210/jc.2004-0835.

De Waele K, Ishkanian SL, Bogarin R, Miranda CA, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Pacaud D, Chanoine JP: Long-acting octreotide treatment causes a sustained decrease in ghrelin concentrations but does not affect weight, behaviour and appetite in subjects with Prader-Willi syndrome. Europ J Endocrinol / Europ Federat Endoc Societ. 2008, 159 (4): 381-388. 10.1530/EJE-08-0462.

Butler MG, Theodoro MF, Bittel DC, Donnelly JE: Energy expenditure and physical activity in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Amer J Med Genet Part A. 2007, 143 (5): 449-459.

Gourash L, Hanchett JE, Forster JL: Management of Prader-Willi syndrome. Edited by: Butler M, Lee PDK, Whitman BY. 2006, New York: Springer, 395-425. 3

Schmidt H, Pozza SB, Bonfig W, Schwarz HP, Dokoupil K: Successful early dietary intervention avoids obesity in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome: a ten-year follow-up. J Pediat Endocrinol & metab: JPEM. 2008, 21 (7): 651-655.

Miller JL, Lynn CH, Shuster J, Driscoll DJ: A reduced-energy intake, well-balanced diet improves weight control in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013, 26 (1): 2-9. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01275.x.

Schlumpf M, Eiholzer U, Gygax M, Schmid S, van der Sluis I, l’Allemand D: A daily comprehensive muscle training programme increases lean mass and spontaneous activity in children with Prader-Willi syndrome after 6 months. J Pediat Endocrinol & metab: JPEM. 2006, 19 (1): 65-74.

Burman P, Ritzen EM, Lindgren AC: Endocrine dysfunction in Prader-Willi syndrome: a review with special reference to GH. Endocrine reviews. 2001, 22 (6): 787-799. 10.1210/er.22.6.787.

Diene G, Mimoun E, Feigerlova E, Caula S, Molinas C, Grandjean H, Tauber M: Endocrine disorders in children with Prader-Willi syndrome–data from 142 children of the French database. Hormone Res Paediat. 2010, 74 (2): 121-128. 10.1159/000313377.

Deal CL, Tony M, Hoybye C, Allen DB, Tauber M, Christiansen JS, Growth Hormone in Prader-Willi Syndrome Clinical Care Guidelines Workshop P, Collaboration E: Growth hormone research society workshop summary: consensus guidelines for recombinant human growth hormone therapy in prader-willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2013, 98 (6): E1072-E1087. 10.1210/jc.2012-3888.

Eiholzer U, Blum WF, Molinari L: Body fat determined by skin fold measurements is elevated despite underweight in infants with Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. J Pediat. 1999, 134 (2): 222-225. 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70419-1.

Bekx MT, Carrel AL, Shriver TC, Li Z, Allen DB: Decreased energy expenditure is caused by abnormal body composition in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediat. 2003, 143 (3): 372-376. 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00386-X.

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Eickhoff J, Allen DB: Long-term growth hormone therapy changes the natural history of body composition and motor function in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2010, 95 (3): 1131-1136. 10.1210/jc.2009-1389.

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Allen DB: Growth hormone improves body composition, fat utilization, physical strength and agility, and growth in Prader-Willi syndrome: a controlled study. J Pediat. 1999, 134 (2): 215-221. 10.1016/S0022-3476(99)70418-X.

Lindgren AC, Hagenas L, Muller J, Blichfeldt S, Rosenborg M, Brismar T, Ritzen EM: Growth hormone treatment of children with Prader-Willi syndrome affects linear growth and body composition favourably. Acta paediatrica. 1998, 87 (1): 28-31. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1998.tb01380.x.

Festen DA, de Lind van Wijngaarden R, van Eekelen M, Otten BJ, Wit JM, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hokken-Koelega AC: Randomized controlled GH trial: effects on anthropometry, body composition and body proportions in a large group of children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2008, 69 (3): 443-451. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03228.x.

Carrel AL, Moerchen V, Myers SE, Bekx MT, Whitman BY, Allen DB: Growth hormone improves mobility and body composition in infants and toddlers with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediat. 2004, 145 (6): 744-749. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.002.

Festen DA, Wevers M, Lindgren AC, Bohm B, Otten BJ, Wit JM, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hokken-Koelega AC: Mental and motor development before and during growth hormone treatment in infants and toddlers with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2008, 68 (6): 919-925. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03126.x.

Myers SE, Whitman BY, Carrel AL, Moerchen V, Bekx MT, Allen DB: Two years of growth hormone therapy in young children with Prader-Willi syndrome: physical and neurodevelopmental benefits. Amer J Med Genet Part A. 2007, 143 (5): 443-448.

Eiholzer U, l’Allemand D, Schlumpf M, Rousson V, Gasser T, Fusch C: Growth hormone and body composition in children younger than 2 years with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediat. 2004, 144 (6): 753-758.

Myers SE, Carrel AL, Whitman BY, Allen DB: Sustained benefit after 2 years of growth hormone on body composition, fat utilization, physical strength and agility, and growth in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediat. 2000, 137 (1): 42-49. 10.1067/mpd.2000.105369.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Siemensma EP, Festen DA, Otten BJ, van Mil EG, Rotteveel J, Odink RJ, Bindels-de Heus GC, van Leeuwen M, Haring DA: Efficacy and safety of long-term continuous growth hormone treatment in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2009, 94 (11): 4205-4215. 10.1210/jc.2009-0454.

Sipila I, Sintonen H, Hietanen H, Apajasalo M, Alanne S, Viita AM, Leinonen E: Long-term effects of growth hormone therapy on patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Acta paediatrica. 2010, 99 (11): 1712-1718. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01904.x.

Siemensma EP, Tummers-de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Festen DA, Troeman ZC, van Alfen-van der Velden AA, Otten BJ, Rotteveel J, Odink RJ, Bindels-de Heus GC, van Leeuwen M: Beneficial effects of growth hormone treatment on cognition in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: a randomized controlled trial and longitudinal study. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2012, 97 (7): 2307-2314. 10.1210/jc.2012-1182.

Whitman BY, Myers S, Carrel A, Allen D: The behavioral impact of growth hormone treatment for children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome: a 2-year, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2002, 109 (2): E35-10.1542/peds.109.2.e35.

Haqq AM, Stadler DD, Jackson RH, Rosenfeld RG, Purnell JQ, LaFranchi SH: Effects of growth hormone on pulmonary function sleep quality, behavior, cognition, growth velocity, body composition, and resting energy expenditure in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2003, 88 (5): 2206-2212. 10.1210/jc.2002-021536.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Festen DA, Otten BJ, van Mil EG, Rotteveel J, Odink RJ, van Leeuwen M, Haring DA, Bocca G, Mieke Houdijk EC: Bone mineral density and effects of growth hormone treatment in prepubertal children with Prader-Willi syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2009, 94 (10): 3763-3771. 10.1210/jc.2009-0270.

Jorgensen AP, Ueland T, Sode-Carlsen R, Schreiner T, Rabben KF, Farholt S, Hoybye C, Christiansen JS, Bollerslev J: Two years of growth hormone treatment in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome do not improve the low BMD. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2013, 98 (4): E753-E760. 10.1210/jc.2012-3378.

Carrel AL, Myers SE, Whitman BY, Allen DB: Benefits of long-term GH therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome: a 4-year study. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2002, 87 (4): 1581-1585. 10.1210/jc.87.4.1581.

Coupaye M, Lorenzini F, Lloret-Linares C, Molinas C, Pinto G, Diene G, Mimoun E, Demeer G, Labrousse F, Jauregi J: Growth hormone therapy for children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome is associated with improved body composition and metabolic status in adulthood. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2013, 98 (2): E328-E335. 10.1210/jc.2012-2881.

Mogul HR, Lee PD, Whitman BY, Zipf WB, Frey M, Myers S, Cahan M, Pinyerd B, Southren AL: Growth hormone treatment of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome and growth hormone deficiency improves lean body mass, fractional body fat, and serum triiodothyronine without glucose impairment: results from the United States multicenter trial. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2008, 93 (4): 1238-1245. 10.1210/jc.2007-2212.

Sode-Carlsen R, Farholt S, Rabben KF, Bollerslev J, Schreiner T, Jurik AG, Christiansen JS, Hoybye C: Growth hormone treatment in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome: the Scandinavian study. Endocrine. 2012, 41 (2): 191-199. 10.1007/s12020-011-9560-4.

Sanchez-Ortiga R, Klibanski A, Tritos NA: Effects of recombinant human growth hormone therapy in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinic Endocrinol. 2012, 77 (1): 86-93. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04303.x.

Grugni G, Giardino D, Crinò A, Malvestiti F, Ballarati L, Di Giorgio G, Marzullo P: Growth hormone secretion among adult patients with Prader-Willi syndrome due to different genetic subtypes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2011, 34 (7): 493-497.

Feigerlova E, Diene G, Oliver I, Gennero I, Salles JP, Arnaud C, Tauber M: Elevated insulin-like growth factor-I values in children with Prader-Willi syndrome compared with growth hormone (GH) deficiency children over two years of GH treatment. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2010, 95 (10): 4600-4608. 10.1210/jc.2009-1831.

Menendez AA: Abnormal ventilatory responses in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Europ J Pediat. 1999, 158 (11): 941-942. 10.1007/s004310051247.

Schluter B, Buschatz D, Trowitzsch E, Aksu F, Andler W: Respiratory control in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Europ J Pediat. 1997, 156 (1): 65-68. 10.1007/s004310050555.

Williams K, Scheimann A, Sutton V, Hayslett E, Glaze DG: Sleepiness and sleep disordered breathing in Prader-Willi syndrome: relationship to genotype, growth hormone therapy, and body composition. J Clinic Sleep Med: JCSM: Official Public Amer Acad Sleep Med. 2008, 4 (2): 111-118.

Nixon GM, Brouillette RT: Sleep and breathing in Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2002, 34 (3): 209-217. 10.1002/ppul.10152.

Miller J, Silverstein J, Shuster J, Driscoll DJ, Wagner M: Short-term effects of growth hormone on sleep abnormalities in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol & Metab. 2006, 91 (2): 413-417.

Nixon GM, Rodda CP, Davey MJ: Longitudinal association between growth hormone therapy and obstructive sleep apnea in a child with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and Metab. 2011, 96 (1): 29-33. 10.1210/jc.2010-1445.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, de Klerk LW, Festen DA, Hokken-Koelega AC: Scoliosis in Prader-Willi syndrome: prevalence, effects of age, gender, body mass index, lean body mass and genotype. Arch Dis Childhood. 2008, 93 (12): 1012-1016. 10.1136/adc.2007.123836.

Odent T, Accadbled F, Koureas G, Cournot M, Moine A, Diene G, Molinas C, Pinto G, Tauber M, Gomes B: Scoliosis in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatrics. 2008, 122 (2): e499-e503. 10.1542/peds.2007-3487.

Diene G, de Gauzy JS, Tauber M: Is scoliosis an issue for giving growth hormone to children with Prader-Willi syndrome?. Arch Dis Childhood. 2008, 93 (12): 1004-1006. 10.1136/adc.2008.141390.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, de Klerk LW, Festen DA, Duivenvoorden HJ, Otten BJ, Hokken-Koelega AC: Randomized controlled trial to investigate the effects of growth hormone treatment on scoliosis in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2009, 94 (4): 1274-1280. 10.1210/jc.2008-1844.

Lee P: Growth hormone and mortality in Prader-Willi syndrome. Growth Genet Horm. 2006, 22 (2): 17-23.

Tauber M, Diene G, Molinas C, Hebert M: Review of 64 cases of death in children with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS). Amer J Med Genet Part A. 2008, 146 (7): 881-887.

Stevenson DA, Anaya TM, Clayton-Smith J, Hall BD, Van Allen MI, Zori RT, Zackai EH, Frank G, Clericuzio CL: Unexpected death and critical illness in Prader-Willi syndrome: report of ten individuals. Amer J Med Genet Part A. 2004, 124A (2): 158-164. 10.1002/ajmg.a.20370.

Barbara DW, Hannon JD, Hartman WR: Intraoperative adrenal insufficiency in a patient with prader-willi syndrome. J Clinic Med Res. 2012, 4 (5): 346-348.

de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Otten BJ, Festen DA, Joosten KF, de Jong FH, Sweep FC, Hokken-Koelega AC: High prevalence of central adrenal insufficiency in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and Metab. 2008, 93 (5): 1649-1654. 10.1210/jc.2007-2294.

Grugni G, Beccaria L, Corrias A, Crino A, Cappa M, De Medici C, Candia SD, Gargantini L, Ragusa L, Salvatoni A: Central adrenal insufficiency in young adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2013, 79 (3): 371-378. 10.1111/cen.12150.

Corrias A, Grugni G, Crino A, Di Candia S, Chiabotto P, Cogliardi A, Chiumello G, De Medici C, Spera S, Gargantini L: Assessment of central adrenal insufficiency in children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2012, 76 (6): 843-850. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04313.x.

Connell NA, Paterson WF, Wallace AM, Donaldson MD: Adrenal function and mortality in children and adolescents with Prader-Willi syndrome attending a single centre from 1991–2009. Clinic Endocrinol. 2010, 73 (5): 686-688. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03853.x.

Nyunt O, Cotterill AM, Archbold SM, Wu JY, Leong GM, Verge CF, Crock PA, Ambler GR, Hofman P, Harris M: Normal cortisol response on low-dose synacthen (1 microg) test in children with Prader Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2010, 95 (12): E464-E467. 10.1210/jc.2010-0647.

Farholt S, Sode-Carlsen R, Christiansen JS, Ostergaard JR, Hoybye C: Normal cortisol response to high-dose synacthen and insulin tolerance test in children and adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2011, 96 (1): E173-E180. 10.1210/jc.2010-0782.

Vogels A, Moerman P, Frijns JP, Bogaert GA: Testicular histology in boys with Prader-Willi syndrome: fertile or infertile?. J Urol. 2008, 180 (4 Suppl): 1800-1804.

Siemensma EP, de Lind van Wijngaarden RF, Otten BJ, de Jong FH, Hokken-Koelega AC: Testicular failure in boys with Prader-Willi syndrome: longitudinal studies of reproductive hormones. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2012, 97 (3): E452-E459. 10.1210/jc.2011-1954.

Radicioni AF, Di Giorgio G, Grugni G, Cuttini M, Losacco V, Anzuini A, Spera S, Marzano C, Lenzi A, Cappa M: Multiple forms of hypogonadism of central, peripheral or combined origin in males with Prader-Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2012, 76 (1): 72-77. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04161.x.

Eiholzer U, l’Allemand D, Rousson V, Schlumpf M, Gasser T, Girard J, Gruters A, Simoni M: Hypothalamic and gonadal components of hypogonadism in boys with Prader-Labhart- Willi syndrome. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2006, 91 (3): 892-898.

Siemensma EP, van Alfen-van der Velden AA, Otten BJ, Laven JS, Hokken-Koelega AC: Ovarian function and reproductive hormone levels in girls with Prader-Willi syndrome: a longitudinal study. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2012, 97 (9): E1766-E1773. 10.1210/jc.2012-1595.

Crino A, Schiaffini R, Ciampalini P, Spera S, Beccaria L, Benzi F, Bosio L, Corrias A, Gargantini L, Salvatoni A: Hypogonadism and pubertal development in Prader-Willi syndrome. Europ J Pediat. 2003, 162 (5): 327-333.

Schmidt H, Schwarz HP: Premature adrenarche, increased growth velocity and accelerated bone age in male patients with Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. Europ J Pediat. 2001, 160 (1): 69-70. 10.1007/s004310000633.

Siemensma EPC, de Lind van Wijngaarden RFA, Otten BJ, de Jong FH, Hokken-Koelega ACS: Pubarche and serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels in children with Prader–Willi syndrome. Clinic Endocrinol. 2011, 75 (1): 83-89. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.03989.x.

Butler MG, Haber L, Mernaugh R, Carlson MG, Price R, Feurer ID: Decreased bone mineral density in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Amer J Med Genet. 2001, 103 (3): 216-222. 10.1002/ajmg.1556.

Vestergaard P, Kristensen K, Bruun JM, Østergaard JR, Heickendorff L, Mosekilde L, Richelsen B: Reduced bone mineral density and increased bone turnover in prader-willi syndrome compared with controls matched for sex and body mass index—a cross-sectional study. J Pediat. 2004, 144 (5): 614-619. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.056.

Akefeldt A, Tornhage CJ, Gillberg C: ‘A woman with Prader-Willi syndrome gives birth to a healthy baby girl’. Dev Med and Child Neurol. 1999, 41 (11): 789-790.

Schulze A, Mogensen H, Hamborg-Petersen B, Graem N, Ostergaard JR, Brondum-Nielsen K: Fertility in Prader-Willi syndrome: a case report with Angelman syndrome in the offspring. Acta paediatrica. 2001, 90 (4): 455-459.

Miller JL, Goldstone AP, Couch JA, Shuster J, He G, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y, Schmalfuss IM: Pituitary abnormalities in Prader-Willi syndrome and early onset morbid obesity. Amer J Med Genet. 2008, 146A (5): 570-577. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31677.

Vaiani E, Herzovich V, Chaler E, Chertkoff L, Rivarola MA, Torrado M, Belgorosky A: Thyroid axis dysfunction in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome during the first 2 years of life. Clinic Endocrinol. 2010, 73 (4): 546-550.

Butler MG, Theodoro M, Skouse JD: Thyroid function studies in Prader-Willi syndrome. Amer J Med Genet Part A. 2007, 143 (5): 488-492.

Festen DA, Visser TJ, Otten BJ, Wit JM, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hokken-Koelega AC: Thyroid hormone levels in children with Prader-Willi syndrome before and during growth hormone treatment. Clinic Endocrinol. 2007, 67 (3): 449-456. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02910.x.

Butler JV, Whittington JE, Holland AJ, Boer H, Clarke D, Webb T: Prevalence of, and risk factors for, physical ill-health in people with Prader-Willi syndrome: a population-based study. Dev Med and Child Neurol. 2002, 44 (4): 248-255. 10.1017/S001216220100202X.

Eiholzer U, Stutz K, Weinmann C, Torresani T, Molinari L, Prader A: Low insulin, IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels in children with Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. Europ J Pediat. 1998, 157 (11): 890-893. 10.1007/s004310050961.

Talebizadeh Z, Butler MG: Insulin resistance and obesity-related factors in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. Clinic Genet. 2005, 67 (3): 230-239.

Krochik AG, Ozuna B, Torrado M, Chertkoff L, Mazza C: Characterization of alterations in carbohydrate metabolism in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J Pediat Endocrinol & metab: JPEM. 2006, 19 (7): 911-918.

Haqq AM, Muehlbauer MJ, Newgard CB, Grambow S, Freemark M: The metabolic phenotype of Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) in childhood: heightened insulin sensitivity relative to body mass index. J Clinic Endocrinol and metab. 2011, 96 (1): E225-E232. 10.1210/jc.2010-1733.

Acknowledgements

We thank Merrily Poth, MD, Nicole Dobson, MD, Sondra Levin, MD and Cheryl Issa, RD for their critical appraisal and comments that contributed to the final version of this manuscript.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Departments of the Army or Navy nor the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JE contributed substantially to the writing of this manuscript. KV drafted the outline of the manuscript and contributed to the writing. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Emerick, J.E., Vogt, K.S. Endocrine manifestations and management of Prader-Willi syndrome. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2013, 14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2013-14

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-9856-2013-14