Abstract

In this work we investigate a model which describes diffusion in petroleum engineering. The original model, which already generalizes the standard one (usual diffusion equation) to a non-local model taking into account the memory effects, is here further extended to cope with many other different possible situations. Namely, we consider the Hilfer fractional derivative which by its nature interpolates the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative and the Caputo fractional derivative (the one that has been studied previously). At the same time, this kind of derivative provides us with a whole range of other types of fractional derivatives. We treat both the Neumann boundary conditions case and the Dirichlet boundary conditions case and find explicit solutions. In addition to that, we also discuss the case of an infinite reservoir.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In order to modernize the public water service of the town of Dijon, France, Henry Darcy made several experiments and wrote an interesting document which soon formed the basis of the theory of fluid conduction. His work was about the download flow of water through filter sands. He established a (diffusion) equation, well known nowadays as ‘Darcy’s law’, which plays the same role as Fourier’s law in heat conduction theory and Ohm’s law in the electricity conduction theory (see [1, 2]). Of course, this law has its limitations. It is restricted to the situations where the flow through the pores can be modeled as Stokes flows. In particular, for large values of the Reynolds number (or at high values of flow rates) Darcy’s law is not valid anymore. It losses its accuracy. Apart from that, Darcy’s law has proved its usefulness in many applications such as the recovery of fuel from underground oil reservoirs. It defines the rock permeability (which controls the directional movement of the flow rate).

Many researchers have shown interest in this law and have worked extensively on extending and generalizing it to more complicated situations and in different contexts. For instance, they observed that this flow is ‘linear’: Darcy himself assumed that the flow is weak and as such the pressure drop is linearly related to the flow discharge rate. This motivated them to extend this law to the ‘nonlinear’ case. They also considered the case when the inertial forces (and/or the deformation of the solid) are not negligible as compared with those arising from viscosity. In particular, they generalized the law from Stokes to ‘non-Stokes’ flows in porous media. In fact, it has been found that more general physical formulations may be obtained by including new parameters and forces in the equation itself. Moreover, we may mention here the transition from a single phase to multiphase and from fixed to growing porous media.

In [3] Caputo modified the standard diffusion equation

by introducing a fractional derivative (in the sense of Caputo) in Darcy’s law [1] to take into account the memory effects that may prevail in the fluid. The equation became

where denotes the Caputo fractional derivative defined by

Similar equations have been derived in other situations like the one in [4] which describes anomalous subdiffusion particles (and p is the probability density function) and in [5] when studying the Stokes first problem (see also [6]). A natural question which arises is: what about the commonly used Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative,

or other types of fractional derivatives?

It is well known by now that the Caputo fractional derivative is often preferred over the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative at least for two main reasons. The Caputo derivative allows us to use the usual initial data (like ), whereas the Riemann-Liouville derivative requires the prior knowledge of when the order of the equation is α (say ). In addition to that, the Caputo derivative of a constant is zero which is not the case for the Riemann-Liouville derivative.

In the present note, we consider a generalized fractional derivative which encompasses both fractional derivatives as special cases and provides a whole range of other types of fractional derivatives in between. This derivative was introduced by Hilfer in [7–9]

where

and therefore we name it after him. This kind of fractional derivative has already proved its usefulness (see [7–9]), and we are witnessing a growing interest in it. The parameter β when equal to zero gives the Riemann-Liouville derivative and when it takes the value one gives the Caputo derivative. For , we obtain many fractional derivatives interpolating these two types of well-known derivatives.

Using the Laplace-Fourier transform, we find the explicit solution for our equation under appropriate boundary conditions. We prove here that, in our case, all these derivatives when considered in diffusion equation (1) lead to similar solutions. Consequently, there is no major benefit in treating separately these derivatives unless there is a need to unify these treatments.

For more on fractional calculus and more on interesting fractional differential equations and treatments, we refer the reader to [10–15].

In the next section, we present some material needed in our arguments. In Section 3 we consider the modified diffusion equation with Neumann boundary conditions and indicate how to find an explicit solution. Section 4 contains the Dirichlet boundary conditions case. Finally, in Section 5 we treat the infinite reservoir case. Our results are illustrated by some graphs.

2 Preliminaries

In this section we present some definitions and results which will be needed later in our arguments (see [12–15] for more).

Definition 1 The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral of order α of f is defined by

when the right-hand side exists.

Definition 2 The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order α of f is defined by

when the right-hand side exists. Note that

Definition 3 The Caputo fractional derivative of order α of f is defined by

(the prime here is for the derivative) when the right-hand side exists. Note that

The relationship between these two types of derivatives is given by the following theorem.

Theorem 1 [12]

We have

Definition 4 The Hilfer fractional derivative of f of order α and type β is defined by

whenever the right-hand side exists.

Note that when ,

which is the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative (see Definition 2), and when ,

which is the Caputo fractional derivative (see Definition 3).

For , the Laplace transforms of these derivatives are given by

It is clear that the differences in these Laplace transforms are in the ‘initial’ data , and (this last one is natural initial data for the Hilfer derivative).

The natural space for the Hilfer fractional derivative is

where

However, here, since our problem is of order one, solutions must be much smoother.

3 The problem

We shall investigate the following linear generalized fractional diffusion problem:

The different parameters μ, ϕ, , k and A are positive constants which account for the viscosity, porosity, total compressibility, permeability and the area, respectively. This model describes the flow of oil in a finite reservoir. A closely related and interesting work is in [16] but for the normal form of the diffusion.

This problem, for the Caputo fractional derivative, was derived and studied in [17]. Here we consider the more general (Hilfer) fractional derivative which covers both the Riemann-Liouville derivative and the Caputo derivative (in addition to many others for β in the interval ). Following the argument in [17], we introduce the dimensionless variables: , and , where .

The next two lemmas will, in particular, show that we obtain the same explicit solution using the Laplace transform as in the case of Caputo derivative (see [17]).

Lemma 1 If , then , , , , .

Proof From Definition 4, we have, for , ,

Let , we see that

Put , then clearly

Put also , it appears that

The proof is complete. □

Lemma 2 Assume that is continuous on for some , then

Proof Let , then

where M is a bound for on . □

In view of our problem (5), the solution must be at least absolutely continuous. Its continuity nearby zero implies by Lemma 2 that . Therefore all three derivatives have equal Laplace transforms (see (2)-(4)) (if in addition ). This fact together with Lemma 1 shows that the argument in [17] is valid without any changes.

Observe that the change of variables has lead to , which by Theorem 1 implies that both the Riemann-Liouville derivative and the Caputo derivative are equal. Another way to see this fact is from the next two lemmas.

Definition 5 A function (the space of summable functions) is said to have a summable fractional derivative if (the space of absolutely continuous functions).

Lemma 3 [[18], p.48]

If has a summable fractional derivative with , then we have

Lemma 4 [[12], p.95]

If , , then , .

Now, Definition 3, Definition 4 and Lemma 3 imply that

This holds if has a summable fractional derivative that is , which is the case when f itself is absolutely continuous on for some . In our case, is absolutely continuous. Lemma 2 ensures that . Therefore,

by Lemma 4 if is continuous. This is the case if and f is continuously differentiable because maps into (it also maps into , see [19]).

4 Dirichlet boundary conditions

Consider the problem

where , are continuously differentiable and is a forcing term.

Putting , with

we see that

implies

Clearly,

Moreover,

So

In addition to that, we have

Therefore from (8)-(11), satisfies

where

and

Definition 6 The finite Fourier sine transform of , , is defined by

and its inverse is

Theorem 2 The following holds:

where is the finite Fourier cosine transform and

Applying first the Laplace transform to the equation in (12), we find

where and denote the Laplace transforms of P and , respectively.

In view of Lemma 2, equation (13) reduces to

Next, we apply the Fourier sine transform to (14) to get

where the ‘hat’ is for the Fourier sine transform. Therefore,

From the relation

it follows that

Furthermore, it is easy to see that

Using the inverse of the Fourier sine transform, we find

and then, inverting the Laplace transform, we obtain

In view of (15) we have

Now, appealing to the formula

we see that

Further

and

Taking into account (20)-(22) in (19), we obtain

Finally, relation (18) leads to

and gives the explicit solution of problem (7).

5 Explicit solution in an infinite reservoir

In this section we consider a similar problem but in an infinite reservoir, which is the case in many practical situations.

The Laplace transform with respect to the time variable applied to the equation in (25) gives

As and , by the continuity of nearby (see Lemma 2), we get

Next, we apply the Fourier transform () to this last equation (26) to arrive at

Therefore

and hence

Now, the inverse Laplace transform of (27) yields

and the inverse Fourier transform gives

Finally we mention that this type of fractional derivative was also studied in [20] and refer the reader to [21, 22] for other interesting problems and methods.

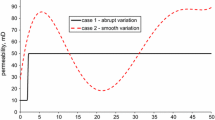

The graphs in Figures 1-6 correspond to different orders and the following data: , , , , .

References

Darcy H: Les Fontaines Publiques de la Ville de Dijon. Dalmont, Paris; 1856.

King M: Darcy’s law and the field equations of the flow of underground fluids. Bull. Int. Assoc. Sci. Hydrol. 1957, 2(1):23-59.

Caputo M: Diffusion of fluids in porous media with memory. Geothermics 1999, 28: 113-130.

Metzler R, Klafter J: The random walk’s guide to anomalous diffusion: a fractional dynamics approach. Phys. Rep. 2000, 339: 1-77.

Salim TO, El-Kahlout A: Solution of fractional order Rayleigh-Stokes equations. Adv. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2008, 1(5):241-254.

Langlands TAM: Solution of a modified fractional diffusion equation. Physica A 2006, 367: 136-144.

Hilfer R: Fractional time evolution. In Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics. Edited by: Hilfer R. World Scientific, Singapore; 2000:87.

Hilfer R: Fractional calculus and regular variation in thermodynamics. In Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics. Edited by: Hilfer R. World Scientific, Singapore; 2000:429.

Hilfer R: Experimental evidence for fractional time evolution in glass materials. Chem. Phys. 2002, 284: 399-408.

Gorenflo R, Mainardi F: Fractional calculus: integral and differential equations of fractional orders. In Fractals and Fractional Calculus in Continuum Mechanics. Springer, New York; 1997.

Herzallah MAE, El-Sayed AMA, Baleanu D: On the fractional-order diffusion-wave process. Rom. J. Phys. 2010, 55(3-4):274-284.

Kilbas AA, Srivastava HM, Trujillo TJ North-Holland Mathematics Studies 204. In Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2006. van Mill, J (ed.)

Miller KS, Ross B: An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York; 1993.

Oldham KB, Spanier J: The Fractional Calculus. Academic Press, New York; 1974.

Podlubny I Mathematics in Sciences and Engineering 198. In Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, San Diego; 1999.

Sandev T, Metzler R, Tomovski Z: Fractional diffusion equation with a generalized Riemann-Liouville time fractional derivative. J. Phys. A, Math. Theor. 2011., 44: Article ID 255203

Malek, NA, Ghanam, RA, Al-Homidan, S: Sensitivity of the pressure distribution to the fractional order α in the fractional diffusion equation (submitted)

Samko SG, Kilbas AA, Marichev OI: Fractional Integrals and Derivatives. Theory and Applications. Gordon & Breach, Yverdon; 1993.

Kou C, Liu J, Ye Y: Existence and uniqueness of solutions for the Cauchy-type problems of fractional differential equations. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2010., 2010: Article ID 142175

Furati KM, Kassim MD, Tatar N-e: Existence and uniqueness for a problem involving Hilfer fractional derivative. Comput. Math. Appl. 2012, 64(6):1616-1626.

Baleanu D, Diethelm K, Scalas E, Trujillo JJ Series on Complexity, Nonlinearity and Chaos. In Fractional Calculus Models and Numerical Methods. World Scientific, Singapore; 2012.

Baleanu D, Machado JAT, Luo AC: Fractional Dynamics and Control. Springer, Berlin; 2012.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support and the facilities provided by King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals and King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) NSTIP research grant No. 11-OIL1663-04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SA and NT solved the problems. RAG participated in establishing the explicit solution and carried out the numerical treatment. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Homidan, S., Ghanam, R.A. & Tatar, Ne. On a generalized diffusion equation arising in petroleum engineering. Adv Differ Equ 2013, 349 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-349

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2013-349