Abstract

In this paper we obtain approximate analytical solutions of systems of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations (FPDEs) by using the two-dimensional differential transform method (DTM). DTM is a numerical solution technique that is based on the Taylor series expansion which constructs an analytical solution in the form of a polynomial. The traditional higher order Taylor series method requires symbolic computation. However, DTM obtains a polynomial series solution by means of an iterative procedure. The fractional derivatives are described in the Caputo fractional derivative sense. The solutions are obtained in the form of rapidly convergent infinite series with easily computable terms. DTM is compared with some other numerical methods. Computational results reveal that DTM is a highly effective scheme for obtaining approximate analytical solutions of systems of linear and nonlinear FPDEs and offers significant advantages over other numerical methods in terms of its straightforward applicability, computational efficiency, and accuracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Mathematical modeling of many physical systems leads to linear and nonlinear fractional differential equations in various fields of physics and engineering. For the last several decades, fractional calculus has found diverse applications in various scientific and technological fields such as control theory, computational fluid mechanics, signal and image processing, and many other physical processes (see, for instance, [1] for further applications).

The numerical and analytical approximations of FPDEs and systems of FPDEs have been an active research area for computational scientists since the work of Padovan [2]. Recently, several mathematical methods including the Adomian decomposition (ADM) [3], variational iteration (VIM) [4], differential transform [5], and homotopy perturbation (HAM) [6] have been developed to obtain exact and approximate analytic solutions of FPDEs. Some of these methods use some sort of transformations in order to reduce equations into simpler equations or systems of equations, and some other methods express the solution in a series form which converges to the exact solution. For instance, VIM and ADM provide immediate and visible symbolic terms of analytic solutions as well as numerical approximate solutions to both linear and nonlinear differential equations without linearization or discretization.

In this paper we use DTM to obtain approximate analytical solutions of systems of nonlinear FPDEs. DTM was not often applied to the solution of systems of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations in the literature. DTM is a numerical solution technique that is based on the Taylor series expansion which constructs an analytical solution in the form of a polynomial. The traditional high order Taylor series method requires symbolic computation. However, DTM obtains a polynomial series solution by means of an iterative procedure. DTM was first applied in the engineering domain in [5]. Recently, the application of DTM was successfully extended to obtain analytical approximate solutions to linear and nonlinear ordinary differential equations of fractional order [7, 8]. The fact that DTM solves nonlinear equations without using Adomian polynomials can be considered as an advantage of this method over the Adomian decomposition method. A comparison between DTM and the Adomian decomposition method for solving fractional differential equations is given in [9]. Further applications of DTM might be seen at [10, 11].

Organization of this paper is as follows. Section 2 overviews fractional calculus briefly and provides some basic definitions and properties of fractional calculus theory. Section 3 describes the generalized two-dimensional DTM. In the same section, several numerical experiments as the application of DTM to some linear and nonlinear systems of FPDEs are presented. Comparison of DTM with HAM and VIM is studied in the final part of the paper.

2 Fractional calculus

There are several different definitions of the concept of a fractional derivative [12]. Some of these are Riemann-Liouville, Grunwald-Letnikow, Caputo, and generalized functions approach. The most commonly used definitions are the Riemann-Liouville and Caputo derivatives.

Definition 2.1 A real function , , is said to be in the space , , if there exists a real number p (>μ) such that , where , and it is said to be in the space iff , .

Definition 2.2 The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral operator of order of a function , , is defined as

It has the following properties. For , , , and :

The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative is mostly used by mathematicians, but this approach is not suitable for physical problems of the real world since it requires the definition of fractional order initial conditions which have no physically meaningful explanation yet. Caputo introduced an alternative definition which has the advantage of defining integer order initial conditions for fractional order differential equations.

Definition 2.3 The fractional derivative of in the Caputo sense is defined as

for , , , .

Lemma 2.1 If , , and , , then

The Caputo fractional derivative is considered here because it allows traditional initial and boundary conditions to be included in the formulation of the problem. In this paper, we have considered some systems of linear and nonlinear FPDEs, where fractional derivatives are taken in Caputo sense as follows.

Definition 2.4 For m to be the smallest integer that exceeds α, the Caputo time-fractional derivative operator of order is defined as

3 Generalized two-dimensional DTM

In this section we shall derive the generalized two-dimensional DTM that we have developed for the numerical solution of linear partial differential equations with space and time-fractional derivatives.

Consider a function of two variables and suppose that it can be represented as a product of two single-variable functions, i.e., . Based on the properties of the generalized two-dimensional differential transform, the function can be represented as

where , , is called the spectrum of . The generalized two-dimensional differential transform of the function is given by

where , k-times. In case of and , the generalized two-dimensional differential transform (1) reduces to the classical two-dimensional differential transform. Next we give some useful theorems about writing the generalized differential transform in equivalent forms under certain conditions.

Theorem 3.1 [13]

Suppose that , , and are the differential transformations of the functions , , and , respectively, then

-

1

if , then ,

-

2

if , , then ,

-

3

if , then ,

-

4

if , then .

Theorem 3.2 [13]

If , , then the generalized differential transform (1) can be written as

Theorem 3.3 [13]

Assume that and the function , where and has the generalized Taylor series expansion . If

-

(a)

and α is arbitrary or

-

(b)

and α is arbitrary and for , where .

Then the generalized differential transform (1) becomes

Theorem 3.4 [13]

If , and , then the generalized differential transform (1) can be written as

In the next section, we apply DTM to some systems of FPDEs which might have applications in mathematical biology and computational chemistry.

4 Analytical solutions of systems of linear and nonlinear FPDEs

Example 1 Consider the following system of linear FPDEs. For (, ),

with initial conditions and . Using DTM, we can write

The transformed initial conditions are

Substituting (3) in (2), we get the following closed form solutions:

If , we obtain

which are exactly the same as the solutions obtained by HAM converging to the closed-form solutions:

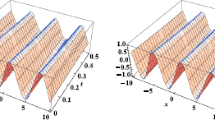

For , Figure 1 illustrates exact and approximate solutions obtained by DTM of and , respectively.

Example 2 Consider the following nonlinear system. For (, ),

with the initial conditions and . The transformed version of (4) is

The transformed version of the initial conditions is

Substituting (7) in (5) and (6), we obtained the following closed form solutions:

If , we get , , which are the exact solutions of the system of equations (4).

We can obtain similar figures for this example as well, but for the sake of brevity, we omit those figures.

5 Conclusion and discussion

In this work, the differential transform method is extended to solve linear and non-linear systems of fractional partial differential equations. The present study has confirmed that DTM offers significant advantages in terms of its straightforward applicability, computational efficiency, and accuracy.

References

Hilfer R (Ed): Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics. Academic Press, Orlando; 1999.

Padovan J: Computational algorithms for FE formulations involving fractional operators. Comput. Mech. 1987, 5: 271–287.

Wu L, Xie L, Zhang J: Adomian decomposition method for nonlinear differential-difference equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2009, 14(1):12–18. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2007.01.007

Odibat Z, Momani S: Application of variational iteration method to nonlinear differential equations of fractional order. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2006, 7(1):15–27.

Zhou JK: Differential Transformation and Its Applications for Electrical Circuits. Huazhong University Press, Wuhan, China; 1986.

Xu H, Liao S, You X: Analysis of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations with the homotopy analysis method. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2009, 14(4):1152–1156. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2008.04.008

Ma S, Xu Y, Yue W: Existence and uniqueness of solution for a class of nonlinear fractional differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2012., 2012: Article ID 133. doi:10.1186/1687–1847–2012–133

Khan NA, Jamil M, Ara A, Khan N-U: On efficient method for system of fractional differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2011., 2011: Article ID 303472. doi:10.1155/2011/303472

Arikoglu A, Ozkol I: Solution of fractional differential equations by using differential transform method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 34: 1473–1481. 10.1016/j.chaos.2006.09.004

Momani S, Odibat Z, Erturk V: Generalized differential transform method for solving a space and time fractional diffusion-wave equation. Phys. Lett. A 2007, 370(5–6):379–387. 10.1016/j.physleta.2007.05.083

Ravi Kanth ASV, Aruna K: Differential transform method for solving linear and non-linear systems of partial differential equations. Phys. Lett. A 2008. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2008.10.008

Podlubny I: Fractional Differential Equations. An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, Some Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications. Academic Press, San Diego; 1999.

Jafari H, Seifi S: Solving a systems of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations using homotopy analysis method. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2009, 14: 1962–1969. 10.1016/j.cnsns.2008.06.019

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The idea of applying the differential transform method (DTM) to the systems of fractional partial differential equations (FPDE) came up as a result of a sequence of scientific discussions by the authors. We, the authors, all together, realized that the DTM has not often been applied to the system of FPDEs in the literature. In particular, AS suggested to applying derivative in the Caputo fractional derivative sense which is different from other fractional derivatives. MAA made a literature search about the related work and tried to found the useful theorems about the subject. AS and AC applied the DTM to some systems of FPDEs. AS implemented the solution algorithm in the Maple programming language. Finally, the authors interpreted the results all together.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Secer, A., Akinlar, M.A. & Cevikel, A. Efficient solutions of systems of fractional PDEs by the differential transform method. Adv Differ Equ 2012, 188 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2012-188

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-1847-2012-188