Abstract

Spinal epidural lipomatosis is a rare complication of chronic corticosteroid treatment. We report a new pediatric case and an analysis of this and 19 pediatric cases identified in the international literature. The youngest of these combined 20 patients was 5 years old when lipomatosis was diagnosed. Lipomatosis manifested after a mean of 1.3 (+/- 1.5) years (SD) (median, 0.8 years; range, 3 weeks - 6.5 years) of corticosteroid treatment. The corticosteroid dose at the time of presentation of the lipomatosis ranged widely, between 5 and 80 mg of prednisone/day. Back pain was the most common presenting symptom. Imaging revealed that lipomatosis almost always involved the thoracic spine, extending into the lumbosacral region in a subset of patients. Predominantly lumbosacral involvement was documented in only two cases. Although a neurological deficit at presentation was documented in about half of the cases, surgical decompression was not performed in the cases reported after 1996. Instead, reducing the corticosteroid dose (sometimes combined with dietary restriction to mobilize fat) sufficed to induce remission. In summary, pediatric spinal epidural lipomatosis remains a potentially serious untoward effect of corticosteroid treatment, which, if recognized in a timely manner, can have a good outcome with conservative treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal epidural lipomatosis is a rare but well documented untoward effect of chronic corticosteroid treatment that was first described 1975 in an adolescent treated with corticosteroids after a kidney transplant [1]. Besides this iatrogenic etiology, there are idiopathic cases that share adiposity as a risk factor [2, 3] and may manifest even in the pediatric age group [4]. Independent of the cause, an overgrowth of fatty tissue in the epidural sac leads to back pain and symptoms of spinal nerve or cord compression, depending on the location and extent of the lesion. Diagnosis is best made by spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and treatment consists of steroid reduction, which is sometimes combined with dietary restriction of carbohydrate or fat intake to help metabolize the fat. Surgical decompression by laminectomy is reserved for severe cases [2]. The exact pathogenic mechanism of corticosteroid-associated epidural lipomatosis is unclear. Although it likely represents a subtype of iatrogenic Cushing syndrome, it remains to be explained why only a small percentage of individuals on chronic corticosteroid treatment develop an accumulation of fatty tissue at this particular anatomic site. Whereas epidural lipomatosis in adults has been subject to relatively large studies [2], only case reports [1, 5–14] and three small series [15–17] have dealt with this entity in the pediatric age group. We now present a new pediatric case of corticosteroid-associated spinal epidural lipomatosis and an updated analysis of the pediatric cases published in the international literature.

Patients and Methods

Case report

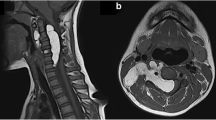

A 10-year-old Caucasian girl (weight, 36 kg) presented with pain of the ear helices and pain and swelling of several ribs bilaterally. There was a history of chronic bilateral Achilles tendonitis and right knee arthritis. One week later, the patient developed laryngeal pain, and otolaryngologic evaluation revealed a partially paralyzed vocal cord. Taken together, these findings established a clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis. The patient was also noted to have bilateral sacroiliac (SI) joint tenderness, and MRI revealed SI joint synovitis. Treatment with methylprednisolone (1 g/d i.v. × 3 d), prednisone (1 mg/kg/d), methotrexate (0.5 mg/kg s.c. once weekly) and etanercept (25 mg s.c. once weekly) was initiated. After one month, the prednisone was reduced to 30 mg/day. Due to the inability to taper the corticosteroids below 15 mg/day, etanercept was switched to anakinra (100 mg s.c. daily) and intravenous immunoglobulins (2 g/kg) after 3 months. Because of persistent clinical activity and pain at the injection sites, cytokine blockade was switched from anakinra to infliximab one month later, and methylprednisolone infusions were resumed. At the end of this month, the patient developed swelling and increasing pain of the lower back. She had gained 11.5 kg, and her body mass index (BMI) had increased from 20.7 (79th percentile) to 23.6 (95th percentile), respectively, by this time. In addition to fluid along the myofascial border and persisting bilateral sacroiliitis, an MRI of the spine and back demonstrated marked epidural lipomatosis involving spinal segments T1-S5 (Figure 1). Assuming that the lipomatosis was the cause of the worsening back pain, methylprednisolone infusions were discontinued and prednisone was tapered from 30 mg daily to 10 mg daily over a 4-week period. Indeed, these changes gradually lead to a complete remission of the back pain without worsening of the polychondritis. A follow up MRI was not performed because of this dramatic improvement. The patient remains free of back pain at 15 months of follow up.

MRI including the lumbar spine, demonstrating spinal epidural lipomatosis in the presented patient after 4.5 months of treatment with prednisone and methylprednisolone. The arrows point to selected areas of the pathological accumulation of fatty tissue in the epidural space. This was not present in a baseline MRI performed before initiation of corticosteroid therapy (image not shown). T1 weighted images; A, sagittal plane; B, axial plane.

Analysis of the literature

PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure [CNKI (available at http://www.cnki.net)] were searched for the terms "lipomatosis AND [spine OR spinal OR epidural]". The identified reports were screened manually for patients fulfilling inclusion criteria (corticosteroid treatment, age of onset of lipomatosis before the 18th birthday) and for additional reports. Sixteen cases were identified and pooled with the 3 cases published by us recently [17]. Together with the presented new case, 20 cases were thus available for analysis.

Results

Results of the literature analysis and the presented case are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 and Figure 2. The average age at diagnosis of epidural lipomatosis was 11 (+/-3.4) years (SD) (median, 11; range, 5-17) (Figure 2a). Eleven patients (55%) were boys. Corticosteroids were given for nephrotic syndrome in 6 cases (33%), after organ transplantation in 4 cases (20%), for juvenile idiopathic arthritis in 3 cases (15%), for systemic lupus erythematosus in 2 cases (10%), and for one case each of Crohn disease, Sjögren syndrome, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, pineoblastoma, and relapsing polychondritis (presented case). Epidural lipomatosis was diagnosed after a mean 1.3 (+/-1.5) years (SD) (median, 0.8 years; range, 3 weeks - 6.5 years) of corticosteroid treatment. Most cases (17/20) presented within the first 18 months of treatment, and one case (patient 19) after only 3 weeks (Figure 2b). Back pain was among the presenting symptoms in nearly all patients (16 patients, 80%) and was the only documented symptom in 8 patients (40%). A neurological deficit was documented in 10 patients (50%) at the time of diagnosis, with lower extremity weakness being the most common one. The diagnosis was made by MRI in all patients published since 1996. Imaging revealed that the lipomatosis almost always involved the thoracic spine. Lumbosacral and/or cervical spine involvement usually resulted from extension of lipomatosis that also involved the thoracic spine. Preferential involvement of the lumbosacral spine occurred in only two cases (9 and 17), and isolated cervical involvement was not reported. Surgical decompression was performed in only 5 cases (25%), all of which were published before 1997. In the other cases, reduction of corticosteroids (combined with a low-carbohydrate and/or low-fat diet and caloric restriction in 4 cases) sufficed to reduce lipomatosis-associated symptoms. In several patients, corticosteroids had to be tapered despite persisting activity of the underlying medical condition. In patient 14 this was facilitated by increasing the cyclosporine A dose [13], in patients 16 and 17 by stepping up disease-modifying therapy by introducing B cell depletion with rituximab [17], in patient 19 by adding the immunosuppressant everolimus [14], and in the presented case by switching to a different tumor necrosis factor-α blocker. The outcome was good in all cases, except for pt. 4 and 12 who died from progression of a malignancy and from sepsis, respectively, shortly after the lipomatosis was diagnosed. Patient 18 experienced remission of the lipomatosis but died from macrophage activation syndrome 1 year later. Importantly, permanent neurological lesions were not reported in any of the cases and did definitively not develop in patients 16-18 and 20, all of whom are known to the authors of this report.

Dot plots illustrating the spread of age (A) and duration of corticosteroid treatment (B) at the time of diagnosis of epidural lipomatosis. Values were obtained from the review of the 19 published cases and the presented case (Table 1). Each dot represents the value from one patient. Horizontal lines, median.

Discussion

The presented case illustrates the general features of epidural lipomatosis that were identified with the literature analysis: onset of symptoms in the context of a pronounced iatrogenic Cushing syndrome --even after a relatively short duration of corticosteroid treatment--, back pain as the most common presenting symptom, and a good neurological outcome without surgical intervention. Therefore, new onset or worsening back pain in a patient on chronic corticosteroid treatment should be warning signs of epidural lipomatosis. Considering the documented value of MRI in the early detection of epidural lipomatosis [15], a spinal MRI should be performed when these warning signs are present. A marked increase in BMI, due to a corticosteroid-induced Cushing syndrome, had taken place in our patient by the time the lipomatosis manifested. In the literature analysis it was not possible to calculate BMIs before initiation of corticosteroid treatment and at the time of diagnosis in a sufficient number of cases. However, features of a Cushing syndrome were documented in most of the cases, thus supporting the notion that corticosteroid-associated epidural lipomatosis represents a variant outcome of iatrogenic Cushing syndrome. As substantiated by the clinical improvement in our patient and by the results of the literature analysis, reducing corticosteroid dosing should be the first-line intervention when epidural lipomatosis is detected. However, it may be difficult to do this without compromising treatment of the underlying chronic illness. As documented in patients 12, 16, 17, 19 and 20, intensifying the disease-modifying treatment regimen with a potentially steroid-sparing agent should be considered strongly. In addition, in patients 16 and 17 prednisone was discontinued in favor of deflazacort, a corticosteroid that may have similar immunosuppressive effectiveness as prednisone but lower glucocorticoid side effects [18]. The role of adjunct dietary interventions geared toward mobilizing fat deposits remains to be defined better. In summary, epidural lipomatosis represents a rare but potentially serious complication of chronic corticosteroid treatment, which, if diagnosed in a timely manner, can be treated effectively with tapering corticosteroids.

It should be pointed out that this analysis of published cases is subject to the well known pitfalls of publication bias. Thus, relatively straight forward cases with a good outcome are likely under reported and may be more common than can be gleaned from our analysis. The authors of this report would therefore welcome input from colleagues around the world who are interested in formulating larger and prospective studies relating to corticosteroid-induced epidural lipomatosis in the pediatric age group.

Consent

Consent for publication of this report was obtained from the patient and her parents and is available for review by the editors of Pediatric Rheumatology.

References

Lee M, Lekias J, Gubbay S, Hurst P: Spinal cord compression by extradural fat after renal transplantation. Med J Aust. 1975, 1: 201-3.

Al-Khawaja D, Seex K, Eslick GD: Spinal epidural lipomatosis--a brief review. J Clin Neurosci. 2008, 15: 1323-6. 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.03.001.

Qasho R, Ramundo OE, Maraglino C, Lunardi P, Ricci G: Epidural lipomatosis with lumbar radiculopathy in one obese patient. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1997, 20: 206-9. 10.1007/BF01105566.

Sener RN: Epidural, paraspinal, and subcutaneous lipomatosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2003, 33: 655-7. 10.1007/s00247-003-0977-7.

George WE, Wilmot M, Greenhouse A, Hammeke M: Medical management of steroid-induced epidural lipomatosis. N Engl J Med. 1983, 308: 316-9. 10.1056/NEJM198302103080605.

Perling LH, Laurent JP, Cheek WR: Epidural hibernoma as a complication of corticosteroid treatment. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1988, 69: 613-6. 10.3171/jns.1988.69.4.0613.

Quint DJ, Boulos RS, Sanders WP, Mehta BA, Patel SC, Tiel RL: Epidural lipomatosis. Radiology. 1988, 169: 485-90.

Arroyo I, Barron K, Brewer EJ: Spinal cord compression by epidural lipomatosis in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31: 447-51. 10.1002/art.1780310320.

Vazquez L, Ellis A, Saint-Genez D: Epidural lipomatosis after renal transplantation--complete recovery without surgery. Transplantation. 1988, 46: 773-774. 10.1097/00007890-198811000-00028.

Shirai I, Ando K: Spinal epidural lipomatosis during steroid therapy (in Japanese). Shoni Naika. 1990, 22: 795-799.

Munoz A, Barkovich J, Mateos F, Simon R: Symptomatic epidural lipomatosis of the spinal cord in a child: MR demonstration of spinal cord injury. Pediatr Radiol. 2002, 32: 865-868. 10.1007/s00247-002-0811-7.

Miller D, Blaser S, Laxer R: Clinical images: epidural lipomatosis in a 14-year-old boy with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 1291-10.1002/art.10285.

Kano K, Yamada Y, Shiraiwa T, Shimizu A, Nishikura K, Arisaka O, Tomita S, Ueda Y: Effectiveness of high trough levels of cyclosporine for 5 months in a case of steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome with severe steroid toxicity. Nephrology (Carlton). 2004, 9: 414-7. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2004.00341.x.

Caruba T, Brunie V, Bousseau V, Guillemain R, Prognon P, Begue D, Sabatier B: Substitution of corticosteroid with everolimus after lung transplantation: a pediatric case report. Pharm World Sci. 2010, 32: 347-9. 10.1007/s11096-010-9376-y.

Kano K, Kuwashima S, Kyo K, Ando T, Ichimura T: Steroid-induced epidural lipomatosis in nephritic children: early recognition with MR imaging. Dokkyo J Med Sci. 1996, 23: 185-191.

Kano K, Kyo K, Ito S, Nishikura K, Ando T, Yamada Y, Arisaka O: Spinal epidural lipomatosis in children with renal diseases receiving steroid therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005, 20: 184-9. 10.1007/s00467-004-1723-6.

Möller J, Girschick HJ, Hahn G, Pessler F: [Steroid-induced spinal epidural lipomatosis in pediatric patients]. Z Rheumatol. 2010, 69: 447-9.

Gonzalez-Perez O, Luquin S, Garcia-Estrada J, Ramos-Remus C: Deflazacort: a glucocorticoid with few metabolic adverse effects but important immunosuppressive activity. Adv Ther. 2007, 24: 1052-60. 10.1007/BF02877711.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Lie Dai (Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China) for searching the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure database, and Dr. Thibaut Caruba (Hopital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France) for providing additional information about patient 19. Aspects of this manuscript were published previously in German in the Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie [17] and were included here with kind permission of Springer Verlag and the editors of Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie. Publication of this report was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JM participated in data collection and writing the manuscript. RQC contributed the case report and edited the manuscript. DWY contributed the MR image and its radiographic interpretation. HJG, DL, DDS, AK, and KS participated in data collection and edited the manuscript. FP initiated and oversaw the study, participated in writing the manuscript and is responsible for its final editing. He had access to all data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Möller, J.C., Cron, R.Q., Young, D.W. et al. Corticosteroid-induced spinal epidural lipomatosis in the pediatric age group: report of a new case and updated analysis of the literature. Pediatr Rheumatol 9, 5 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-5