Abstract

Autoimmunity is often observed among individuals with primary immune deficiencies; however, the frequency and role of autoimmunity in Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia (SIOD) has not been fully assessed. SIOD, which is caused by mutations of SMARCAL1, is a rare autosomal recessive disease with its prominent features being skeletal dysplasia, T cell deficiency, and renal failure. We present a child with severe SIOD who developed rituximab resistant Evans syndrome (ES). Consistent with observations in several other immunodeficiency disorders, a review of SIOD patients showed that approximately a fifth of SIOD patients have some features of autoimmune disease. To our best knowledge this case represents the first patient with SIOD and rituximab resistant ES and the first study of autoimmune disease in SIOD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The immune system has evolved to clear pathogens efficiently and to tolerate self. The establishment and maintenance of self-tolerance is a requirement of adaptive immunity. To accomplish this, central tolerance removes self-reactive T cells during thymic development and peripheral tolerance represses self-reactive T cells that escape central tolerance checkpoints. Breakdown of either central or peripheral tolerance can lead to autoimmunity.

One such autoimmune disease is Evans syndrome (ES), which was first described in 1951 [1]. ES is defined by a combination (either simultaneously or sequentially) of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in the absence of an identifiable underlying pathology; ES can also include immune neutropenia [1]. Pediatric ES generally has a chronic course of frequent exacerbations and remissions and a mortality of 7-36%. Most patients respond to corticosteroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), but relapse is frequent. Second-line therapies therefore include splenectomy or immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine A (CsA), mycophenolate mophetil [1]. Recently, consistent with the hypothesis that ES arises from dysregulation of B cells, the monoclonal antibody against the B-cell antigen CD20, rituximab, has shown much promise for treatment of ES [1].

ES may be associated with other diseases or conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus [2], lymphoproliferative disorders [3, 4], or primary immunodeficiencies [5]. The primary immunodeficiencies, which are genetic disorders causing partial immune system dysfunction, are often characterised by aberrant inflammatory responses and autoimmunity [6]. Well-studied examples of this include autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis and ectodermal dystrophy (APECED), immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked inheritance (IPEX), autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), Omenn syndrome, C1q deficiency, interleukin-2 receptor alpha-chain deficiency and common variable immunodeficiency [7–11].

A less well-studied immunodeficiency is Schimke immunoosseous dysplasia (SIOD) [12]. SIOD, which was first described by Schimke et al. in 1971 [13], is a rare multisystem autosomal recessive disorder consisting of facial dysmorphism, spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia leading to dysproportionate growth failure, T-cell immunodeficiency and nephropathy characterised by steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome and frequently focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [14, 15]. Additional features include ischemic cerebral attacks, migraine-like headaches, hematologic abnormalities of leucopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia, enteropathy, hyperpigmented skin macules, unusual hair and microdontia [15–17]. The course of the disease varies from severe with intrauterine or early childhood onset and death in childhood [15, 18, 19] to milder disease with survival into adulthood [15, 20]. For both severe and mild disease, the therapy is mainly symptomatic [15].

SIOD is caused by biallelic mutations in SMARCAL1 (SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily-a-like-1), which encodes a DNA annealing helicase with homology to the SNF2 chromatin remodelling proteins [21]. The SMARCAL1 enzyme plays a role in the DNA stress response and regulates gene expression [22–27].

We report a child with severe SIOD and rituximab resistant Evans syndrome (ES) preceeding the bone marrow failure that can be associated with SIOD. Combined with prior reports of other autoimmune disorders among individuals with SIOD and upon review of our SIOD patient database, we conclude that the T cell immunodeficiency of SIOD compromises self-tolerance.

Materials

Patients

Patients referred to this study gave informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, TX USA), the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, ON Canada), and the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC Canada). Clinical data were obtained from questionnaires completed by the attending physician as well as medical summaries.

Questionnaires

Physicians referring SIOD patients for molecular testing for SIOD complete a questionnaire on the patient being referred. Included in this questionnaire, is a question on whether the patient has an autoimmune disorder and if so to specify the problem, serology and therapy. In addition, there are specific questions asking if the patient had lymphocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, or thrombocytopenia as well as the nature of the cytopenia and any effective therapies.

Results

Case

The proposita was a 4.5-year-old girl born to non-consanguineous parents by caesarean section at 36 weeks of gestation following a pregnancy complicated by intrauterine growth retardation. Her birth weight, length and head circumference were 1450 g (< 3rd percentile), 39 cm (< 3rd percentile) and 34 cm (25th percentile), respectively. She did well in the newborn period with the exception of a self-limited thrombocytopenia. Her abdominal ultrasound detected left-sided unilateral renal agenesis (URA), but her voiding cystography was normal.

She was presented to our centre at the age of 3 years with nephrotic proteinuria of 1-2 g/m2/day without hematuria and a blood pressure of 90/65 mmHg (diastolic - 95th percentile for height). On clinical examination, she had a high-pitched voice, low nasal bridge, short neck and trunk, disproportionate short stature, lumbar lordosis, protruding abdomen and numerous pigmented macules predominantly on her trunk. Her weight was 7.3 kg (< 3rd percentile), and her length was 72 cm (< 3rd percentile). She had normal neurologic development. Initial laboratory studies showed a normal blood count (WBC 5.2 cells per nl, HGB 13.8 g/dl, PLT 415 cells per nl), urea (3 mmol/l), creatinine (28 μmol/l), albumin (38.1 g/l), total protein (65.4 g/l), triglycerides (0.66 mmol/l), cholesterol (7 mmol/l), TSH (4.5 mIU/l), and free T4 (18.1 pmol/l). She also had normal growth hormone function tests. Immunological exam revealed deficiency of CD4+ and CD8+ cells and increased CD4+/CD8+ ratio. Her laboratory results are summarised in tables 1 and 2.

Because of her immunodeficiency, she developed multiple infections. At the age of 3.5 years, she had Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia with positive serology and required hospitalization for parenteral antibiotics. By the age of 4.5 years, she developed severe leucopenia and recurrent protracted infections including Candida albicans sepsis and Epstein Barr virus infection with fever and persistently high viral load associated with a decreased WBC.

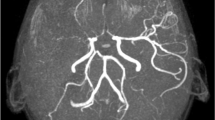

At 4 years, she was hospitalized in status epilepticus. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging showed multiple ischemic changes and narrowing of the middle cerebral artery bilaterally. The seizures responded to phenobarbital; however, she had additional cerebral infarcts and became triplegic with motoric aphasia.

To treat her multiple problems, we initated several therapies. For her nephrotic syndrome, we tried a 6 week course of prednisone (60 mg/m2/day); however, she did not respond and her subsequent renal biopsy showed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. For treatment of her hypertension, we intially used the ACE inhibitor ramipril (2.5 mg daily) and subsequently the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan (12.5 mg daily); her arterial blood pressure declined to the normal range for her age and height. For treatment of her hypercholesterolemia, we introduced simvastatin therapy (5 mg daily), and her cholesterol level declined from 11 mmol/l back to 7.1 mmol/l. To control her recurrent infections, she was placed on prophylactic cotrimoxazole; however, the infections persisted and ultimately she died at 5.5 years from multiorgan failure secondary to Enterobacter cloacae sepsis.

Based on her renal failure, T-cell deficiency and dysmorphic features, we suspected the diagnosis of SIOD. Her skeletal radiographs also demonstrated the typical features including flattened capital femoral epiphyses, dysplastic acetabular fossae and marked thoracic kyphosis. To confirm the diagnosis molecularly, we sequenced PCR amplification products for the coding exons of SMARCAL1. This identified mutations c.2542G > T (p. Glu848X) in exon 17 and c.1439C > T (p.Pro480Leu) in exon 8; both of these mutations have been described previously in patients with SIOD [20, 21]. Confirming compound heterozygosity, c.2542G > T was inherited from her mother and c.1439C > T was inherited from her father.

In addition to the above problems, the proposita developed ITP and anemia without splenomegaly in the latter half of her 5th year of life. The ITP was characterised by severe thrombocytopenia (8 cells per nl) and antiplatelet antibodies detectable by the immunobead assay. A year after her mycoplasma pneumonia, two months after onset of her ITP and before therapy with IVIG, she developed anemia (HGB 7 g/dl, reticulocytes 3.1%, LDH 7.61 μkat/l, bilirubin 11 μmol/l); this was accompanied by a direct antiglobulin test (DAT) that was positive for auto-antierythrocyte antibodies. She received one platelet transfusion and two red blood cell transfusions shortly after the diagnosis of her ITP and DAT-positive anemia, respectively.

Bone marrow aspirations performed at the onset of her ITP and again 3 months later revealed reduced platelet production despite normal numbers, size and morphology (nuclear separation) of megakaryocytes. Each also showed normal to hypercellular trilinear hematopoesis without dysplasia (myeloid precursors 47.2%, erythroid precursors 25%). Overall the bone marrow morphology was compatible with immune cytopenia and atypical for bone marrow failure. Based on this combination of findings and her clinical features, the proposita was diagnosed with ES.

Her ES responded poorly to standard therapies. It did not respond to corticosteroids or to IVIG alone. However, after a month of combination therapy with prednisone (2 mg/kg/day) and CyA (3-4 mg/kg/day) the platelet count and HGB level rose to the lower normal range. Unfortunately, the thrombocytopenia reoccured when the prednisone dose was weaned after 2 months; the relapse, which precipitated bleeding complications, was unresponsive to combined therapy with IVIG and high dose steroids as well as to rituximab (4 doses of 375 mg/m2). Throughout this time, the persistently DAT-positive anemia progressed such that she required 8 transfusions in the last months of her life.

Ten months after presenting with thrombocytopenia and eight months after the development of anemia, the proposita had the onset of progressive neutropenia. She did not have anti-neutrophil antibodies; therefore, we interpreted this as the onset of bone marrow failure. Concomitent with this she developed a severe coagulopathy and required four platelet transfusions.

Autoimmune disease occurs commonly in SIOD patients

To ascertain whether the autoimmune disease observed in the proposita was unique to her or part of the clinical symptoms of SIOD, we sent questionnaires to 63 physicians of SIOD patients in whom we had identified SMARCAL1 mutations (Table 3), and 41 physicians reported checking for autoimmune disease in their patients. Among the 41 patients, 2 female and 6 male patients had one or more indications of autoimmune disease. These manifestations included thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, enteropathy, and pericarditis with anti-cardiolipin antibodies. In one patient with thrombocytopenia, the autoimmune features resolved spontaneously, in another after bone marrow transplantation and in another after splenectomy. All other patients were successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy: steroids, cyclophosphamide or IVIG.

Discussion

As observed for SIOD [15, 28, 29], many other primary immune deficiencies are characterized by infections as well as a defect in self-tolerance. For example, APECED, ALPS and IPEX are defined by the occurrence of autoimmune diseases, whereas for other immune deficiencies the autoimmune manifestations are not as prominent [7–11]. Immunodeficiencies with less prominent autoimmune manifestations include common variable immunodeficiency [30, 31], Good syndrome [32], hyper-IgM syndrome [33], WAS [34, 35], and idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia [36]. About 22% of individuals with common variable immunodeficiency have autoimmune problems, and these include autoimmune cytopenias, pernicious anemia, thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis and vitiligo [30, 31]. Approximately a quarter of individuals with hyper-IgM syndrome develop an autoimmune problem such as cytopenia, nephritis, enteropathy, hepatitis, arthritis, hypothyroidism or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [33]. About half of individuals with WAS have autoimmune problems including neutropenia, arthritis, vasculitis, uveitis, enteropathy and nephritis [34, 35]. Similarly, about 20-25% of those with idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia develop an autoimmune problem such as SLE, antiphospholipid syndrome, Grave's disease, colitis, thyroiditis and vitiligo [36]. Similar to these diseases, SIOD also has variable expression of autoimmune manifestations (Table 3).

The etiology of the autoimmune problems among SIOD patients remains undefined and no consistent inflammatory or serological markers have been reported [15]. As for the immunodeficiency, however, it likely arises from a dysfunction of SMARCAL1, the enzyme mutated in SIOD [21], within the lymphocytic lineages. Consistent with such a cell autonomous model, SMARCAL1 is highly expressed in the bone marrow lineages, and the limited data on one SIOD patient suggests that bone marrow transplantation can ameliorate the immunodeficiency [37, 38].

Conclusion

In conclusion, we report the first SIOD patient with autoimmune problems unresponsive to immunosuppression with steroids, CsA and rituximab. Additionally, we define the frequency and spectrum of autoimmune manifestions in SIOD.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ACLA:

-

anti-cardiolipin antibody

- ACE:

-

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ALPS:

-

autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome

- ANA:

-

antinuclear antibody

- ANCA:

-

anti-neutrophil cytoplasmatic antibody

- APECED:

-

autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis and ectodermal dystrophy

- ATA:

-

anti-transglutaminase antibody

- C1q:

-

complement factor 1q

- C3:

-

complement factor 3

- C4:

-

complement factor 4

- CD:

-

cluster of differentiation protein

- cm:

-

centimeter

- CsA:

-

cyclosporine A

- dl:

-

deciliter

- DNA:

-

deoxyribonucleic acid

- ENA:

-

endonuclear antibody

- ES:

-

Evans syndrome

- F:

-

female

- g:

-

gram

- HGB:

-

hemoglobin

- Ig:

-

immunoglobulin

- IPEX:

-

immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy; enteropathy and X-linked inheritance

- IVIG:

-

intravenous immunoglobulins

- l:

-

liter

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- M:

-

male

- m2:

-

square meter

- mg:

-

milligram

- μmol:

-

micro mole

- mmol:

-

millimole

- nl:

-

nanoliter

- NM:

-

not measured

- p.:

-

protein

- PLT:

-

platelet

- SIOD:

-

Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia

- SLE:

-

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SMARCAL1:

-

SWI/SNF-related matrix associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin; subfamily A-like protein 1

- TSH:

-

thyroid-stimulating hormone

- URA:

-

unilateral renal agenesis

- WAS:

-

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

- WBC:

-

white blood cell count.

References

Evans RS, Takahashi K, Duane RT, Payne R, Liu C: Primary thrombocytopenic purpura and acquired hemolytic anemia; evidence for a common etiology. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1951, 87: 48-65.

Deleze M, Oria CV, Alarcon-Segovia D: Occurrence of both hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenic purpura (Evans' syndrome) in systemic lupus erythematosus. Relationship to antiphospholipid antibodies. J Rheumatol. 1988, 15: 611-615.

Garcia-Munoz R, Rodriguez-Otero P, Pegenaute C, Merino J, Jakes-Okampo J, Llorente L, Bendandi M, Panizo C: Splenic marginal zone lymphoma with Evans' syndrome, autoimmunity, and peripheral gamma/delta T cells. Ann Hematol. 2009, 88: 177-178. 10.1007/s00277-008-0555-z.

Hauswirth AW, Skrabs C, Schutzinger C, Raderer M, Chott A, Valent P, Lechner K, Jager U: Autoimmune thrombocytopenia in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Haematologica. 2008, 93: 447-450. 10.3324/haematol.11934.

Michel M, Chanet V, Galicier L, Ruivard M, Levy Y, Hermine O, Oksenhendler E, Schaeffer A, Bierling P, Godeau B: Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura and common variable immunodeficiency: analysis of 21 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004, 83: 254-263. 10.1097/01.md.0000133624.65946.40.

Carneiro-Sampaio M, Coutinho A: Tolerance and autoimmunity: lessons at the bedside of primary immunodeficiencies. Adv Immunol. 2007, 95: 51-82.

Westerberg LS, Klein C, Snapper SB: Breakdown of T cell tolerance and autoimmunity in primary immunodeficiency--lessons learned from monogenic disorders in mice and men. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008, 20: 646-654. 10.1016/j.coi.2008.10.004.

Agarwal S, Cunningham-Rundles C: Autoimmunity in common variable immunodeficiency. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2009, 9: 347-352. 10.1007/s11882-009-0051-0.

Coutinho A, Carneiro-Sampaio M: Primary immunodeficiencies unravel critical aspects of the pathophysiology of autoimmunity and of the genetics of autoimmune disease. J Clin Immunol. 2008, 28 (Suppl 1): S4-10.

Lehman HK, Ballow M: Immune deficiency disorders with autoimmunity and abnormalities in immune regulation-monogenic autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2008, 34: 141-145. 10.1007/s12016-007-8038-x.

Torgerson TR: Immune dysregulation in primary immunodeficiency disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008, 28: 315-327. 10.1016/j.iac.2008.02.002. viii-ix

Spranger J, Hinkel GK, Stoss H, Thoenes W, Wargowski D, Zepp F: Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: a newly recognized multisystem disease. J Pediatr. 1991, 119: 64-72. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81040-6.

Schimke RN, Horton WA, King CR: Chondroitin-6-sulphaturia, defective cellular immunity, and nephrotic syndrome. Lancet. 1971, 2: 1088-1089.

Ehrich JH, Burchert W, Schirg E, Krull F, Offner G, Hoyer PF, Brodehl J: Steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome associated with spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, transient ischemic attacks and lymphopenia. Clin Nephrol. 1995, 43: 89-95.

Boerkoel CF, O'Neill S, Andre JL, Benke PJ, Bogdanovic R, Bulla M, Burguet A, Cockfield S, Cordeiro I, Ehrich JH: Manifestations and treatment of Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: 14 new cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2000, 159: 1-7. 10.1007/s004310050001.

Kaitila I, Savilahti E, Ormala T: Autoimmune enteropathy in Schimke immunoosseous dysplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998, 77: 427-430. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980605)77:5<427::AID-AJMG14>3.0.CO;2-K.

Kilic SS, Donmez O, Sloan EA, Elizondo LI, Huang C, Andre JL, Bogdanovic R, Cockfield S, Cordeiro I, Deschenes G: Association of migraine-like headaches with Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2005, 135: 206-210.

Ehrich JH, Offner G, Schirg E, Hoyer PF, Helmchen U, Brodehl J: Association of spondylo-epiphyseal dysplasia with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990, 4: 117-121. 10.1007/BF00858821.

Hashimoto K, Takeuchi A, Ieshima A, Takada M, Kasagi M: Juvenile variant of Schimke immunoosseous dysplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1994, 49: 266-269. 10.1002/ajmg.1320490304.

Clewing JM, Fryssira H, Goodman D, Smithson SF, Sloan EA, Lou S, Huang Y, Choi K, Lucke T, Alpay H: Schimke immunoosseous dysplasia: suggestions of genetic diversity. Hum Mutat. 2007, 28: 273-283. 10.1002/humu.20432.

Boerkoel CF, Takashima H, John J, Yan J, Stankiewicz P, Rosenbarker L, Andre JL, Bogdanovic R, Burguet A, Cockfield S: Mutant chromatin remodeling protein SMARCAL1 causes Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia. Nat Genet. 2002, 30: 215-220. 10.1038/ng821.

Bansbach CE, Betous R, Lovejoy CA, Glick GG, Cortez D: The annealing helicase SMARCAL1 maintains genome integrity at stalled replication forks. Genes Dev. 2009, 23: 2405-2414. 10.1101/gad.1839909.

Driscoll R, Cimprich KA: HARPing on about the DNA damage response during replication. Genes Dev. 2009, 23: 2359-2365. 10.1101/gad.1860609.

Yusufzai T, Kong X, Yokomori K, Kadonaga JT: The annealing helicase HARP is recruited to DNA repair sites via an interaction with RPA. Genes Dev. 2009, 23: 2400-2404. 10.1101/gad.1831509.

Ciccia A, Bredemeyer AL, Sowa ME, Terret ME, Jallepalli PV, Harper JW, Elledge SJ: The SIOD disorder protein SMARCAL1 is an RPA-interacting protein involved in replication fork restart. Genes Dev. 2009, 23: 2415-2425. 10.1101/gad.1832309.

Postow L, Woo EM, Chait BT, Funabiki H: Identification of SMARCAL1 as a component of the DNA damage response. J Biol Chem. 2009

Morimoto M, Cho K-S, Myung C, Shaw CA, Beirnes K, Leung D, Fam H-K, Choi K, Huang Y, Huang C: Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: a disorder of transcriptional responses to cell signaling?. Submitted. 2011

Hall CM: International nosology and classification of constitutional disorders of bone (2001). Am J Med Genet. 2002, 113: 65-77. 10.1002/ajmg.10828.

Ming JE, Stiehm ER, Graham JM: Syndromes associated with immunodeficiency. Adv Pediatr. 1999, 46: 271-351.

Brandt D, Gershwin ME: Common variable immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2006, 5: 465-470. 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.03.010.

Knight AK, Cunningham-Rundles C: Inflammatory and autoimmune complications of common variable immune deficiency. Autoimmun Rev. 2006, 5: 156-159. 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.002.

Tarr PE, Sneller MC, Mechanic LJ, Economides A, Eger CM, Strober W, Cunningham-Rundles C, Lucey DR: Infections in patients with immunodeficiency with thymoma (Good syndrome). Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001, 80: 123-133. 10.1097/00005792-200103000-00005.

Jesus AA, Duarte AJ, Oliveira JB: Autoimmunity in hyper-IgM syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2008, 28 (Suppl 1): S62-66.

Dupuis-Girod S, Medioni J, Haddad E, Quartier P, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Le Deist F, de Saint Basile G, Delaunay J, Schwarz K, Casanova JL: Autoimmunity in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: risk factors, clinical features, and outcome in a single-center cohort of 55 patients. Pediatrics. 2003, 111: e622-627. 10.1542/peds.111.5.e622.

Sullivan KE, Mullen CA, Blaese RM, Winkelstein JA: A multiinstitutional survey of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. J Pediatr. 1994, 125: 876-885. 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82002-5.

Zonios DI, Falloon J, Bennett JE, Shaw PA, Chaitt D, Baseler MW, Adelsberger JW, Metcalf JA, Polis MA, Kovacs SJ: Idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia: natural history and prognostic factors. Blood. 2008, 112: 287-294. 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127878.

Elizondo LI, Huang C, Northrop JL, Deguchi K, Clewing JM, Armstrong DL, Boerkoel CF: Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: a cell autonomous disorder?. Am J Med Genet A. 2006, 140: 340-348.

Petty EM, Yanik GA, Hutchinson RJ, Alter BP, Schmalstieg FC, Levine JE, Ginsburg D, Robillard JE, Castle VP: Successful bone marrow transplantation in a patient with Schimke immuno- osseous dysplasia. J Pediatr. 2000, 137: 882-886. 10.1067/mpd.2000.109147.

Ludman MD, Cole DE, Crocker JF, Cohen MM: Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia: case report and review. Am J Med Genet. 1993, 47: 793-796. 10.1002/ajmg.1320470538.

Acknowledgements and Funding

This work was supported in part by grant VZ 0006420301 MZOFNM 2005, the Czech Ministry of Health. It was also supported by the March of Dimes (C.F.B.); the Gillson Longenbaugh Foundation (C.F.B.); the Dana Foundation (C.F.B.), the New Development Award, Microscopy, and Administrative Cores of the Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Baylor College of Medicine (C.F.B.); the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation (C.F.B.); the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (C.F.B.); the New Investigator Grant: Institute of Human Development, Child and Youth Health from the SickKids Foundation - Canadian Institutes of Health Research (C.F.B.); the Association Autour D'Emeric et D'Anthony (C.F.B.); and The Little Giants Foundation (C.F.B.). C.F.B. is a scholar of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and a Clinical Investigator of the Child & Family Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JZ wrote the initial manuscript draft. JD, TS and JL supervised the treatment of the patient and assisted in preparing the draft. MS, NS, SS and TR contributed in taking care of the patient and helped the drafting of the manuscript. AK, MB carried out molecular genetic testing and participated in the drafting of the manuscript. EL and EG-N contributed patient information not in the SIOD patient registry. ABH maintains the SIOD patient registry and complied the data in it for this report. CFB provided the SIOD patient registry and SIOD patient information. All authors critically reviewed and revised drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zieg, J., Krepelova, A., Baradaran-Heravi, A. et al. Rituximab resistant evans syndrome and autoimmunity in Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia. Pediatr Rheumatol 9, 27 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-9-27