Abstract

Background

Recent studies have demonstrated the consistently high diagnostic and prognostic value of dobutamine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance (DCMR). The value of DCMR for clinical decision making still needs to be defined. Hence, the purpose of this study was to assess the utility of DCMR regarding clinical management of patients with suspected and known coronary artery disease (CAD) in a routine setting.

Methods and Results

We prospectively performed a standard DCMR examination in 1532 consecutive patients with suspected and known CAD. Patients were stratified according to the results of DCMR: DCMR-positive patients were recommended to undergo invasive coronary angiography and DCMR-negative patients received optimal medical treatment. Of 609 (40%) DCMR-positive patients coronary angiography was performed in 478 (78%) within 90 days. In 409 of these patients significant coronary stenoses ≥50% were present (positive predictive value 86%). Of 923 (60%) DCMR-negative patients 833 (90%) received optimal medical therapy. During a mean follow-up period of 2.1 ± 0.8 years (median: 2.1 years, interquartile range 1.5 to 2.7 years) 8 DCMR-negative patients (0.96%) sustained a cardiac event.

In 131 DCMR-positive patients who did not undergo invasive angiography, 20 patients (15%) suffered cardiac events. In 90 DCMR-negative patients (10%) invasive angiography was performed within 2 years (range 0.01 to 2.0 years) with 56 patients having coronary stenoses ≥50%.

Conclusion

In a routine setting DCMR proved a useful arbiter for clinical decision making and exhibited high utility for stratification and clinical management of patients with suspected and known CAD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Physicians commonly have to determine the need for invasive angiography in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease (CAD). Current guidelines and recent studies have emphasized the importance of non-invasive stress testing for the detection of myocardial ischemic reactions prior to invasive angiography [1–3]. Dobutamine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance (DCMR) is well established for the evaluation of patients with suspected and known CAD [4–9]. Apart from merely detecting stress inducible myocardial ischemia, there is growing evidence supporting the value of DCMR to assess cardiac prognosis [10, 11]. As for other imaging modalities, patients with an intermediate pretest probability for the presence of CAD benefit most from DCMR [12]. However, data on the usefulness of DCMR testing to direct patient treatment regarding medical versus invasive strategies has not been reported yet. Hence, we sought to evaluate the value of DCMR as the sole clinical decision maker in a large unselected patient population and determined its utility for clinical management of patients with suspected and known CAD.

Methods

Patient population

The study was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at the Charité University School of Medicine and written informed consent was given by all patients. Between November 2005 and July 2008, 1699 patients were examined prospectively for the evaluation of chest pain syndromes or dyspnea. Patients were eligible if they had suspected or known CAD including patients with prior interventional or surgical revascularization. Patients with contraindications to either CMR (non-compatible biometallic implants) or dobutamine (e.g. unstable angina, myocarditis, endocarditis) and patients with atrial fibrillation were not considered. All patients were instructed to refrain from beta-blockers 24 hours prior to the MR study. Medical history was obtained immediately before DCMR. Clinical variables were defined according to the Framingham Risk Score assessment [13].

DCMR

As previously described DCMR was performed in the supine position on a 1.5 Tesla Intera CV system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) [7]. Cardiac standard geometries (three short axis views and a four-, two- and three-chamber view) were acquired at rest and during dobutamine/atropine stress to achieve target heart rate, defined as 85% of the maximum predicted heart rate: (220-age) × 0.85. Termination criteria were as previously published [14]. Total examination time was ≈ 30 minutes.

MR Sequences

For cine imaging, balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequences with retrospective gating (50 phases per cardiac cycle) were used during an end-expiratory breath hold [repetition time (TR), 3.4 ms; echo time (TE), 1.7 ms; flip angle, 60°]. In-plane spatial resolution was 1.8 × 1.8 mm with a slice thickness of 8 mm.

Image analysis

The study sought to address the impact of DCMR on clinical management in routine practice, so the results of each study were interpreted at the time of the original examination by cardiologists trained in DCMR. All image analysis was performed on a commercially available View Forum station (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). Segmental analysis of wall motion was performed using a synchronized quad-screen image display and applying a standard 17-segment scoring system during each stage of the protocol (1 = normal, 2 = hypokinetic, 3 = akinetic, or 4 = dyskinetic) [15]. A positive DCMR (DCMR-pos) was defined as a stress inducible wall motion abnormality (IWMA) in ≥ 1 segment; a biphasic response was also considered to indicate a positive DCMR. A negative DCMR (DCMR-neg) was defined as the absence of a stress inducible wall motion abnormality. Left ventricular function was determined using a combined triplane model [16]. DCMR results were made available to the referring physician immediately after finishing the examination using a standardized reporting sheet.

Follow-up

Outcome data were collected from a standardized mailed questionnaire, telephone interview with the patient or a close relative and hospital chart review; all reported clinical events were confirmed by contact with the patient's general practitioner or the treating hospital. Survival information was obtained from the Department of National Registration for patients lost on first contact. Cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction were registered as cardiac events. Cardiac death was defined as death in the presence of acute coronary syndrome, fatal arrhythmia, refractory cardiac failure or sudden unexpected death; nonfatal myocardial infarction was defined by angina and an increase in cardiac-specific enzymes and/or development of new ECG changes (i.e., transient ST-segment elevation). In the case of 2 simultaneous events the worst event was chosen (cardiac death > myocardial infarction). We documented the reasons to perform invasive coronary angiography despite a negative DCMR during the 2 years following the examination with the period being chosen based on data from a previous prognosis study [11]. Conversely, the reasons not to perform invasive angiography within 90 days in patients with a positive DCMR were also noted. Patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting or percutaneous coronary intervention were censored at the time of revascularization.

Coronary Angiography

Invasive coronary angiography was performed at the discretion of the referring physicians. The angiograms were evaluated visually for the presence of significant stenoses (i.e. ≥ 50% luminal diameter reduction) in the three large epicardial coronary arteries and their major branches (i.e. vessel diameter ≥ 2.0 mm) by highly experienced invasive cardiologists.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package release 15.0.1 (Chicago, USA). For all continuous parameters, data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Additionally, follow-up duration is presented as median with lower and upper quartiles. The normality of the distributions was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Comparisons between two groups of continuous data were made with unpaired Student t or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate. Discrete data was analyzed with the chi-square and Fisher's exact test when appropriate. Sensitivity was calculated according to standard definitions. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct plots depicting clinical events as a function of follow-up duration, and curves were compared using the log-rank test. Statistical tests were two-tailed; significance was reached if p < 0.05.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of the initial 1699 patients, 124 were excluded due to claustrophobia (n = 46, 2.7%), technical problems (e.g. ECG mistriggering and insufficient image quality) (n = 17, 1%) and limiting side effects during the administration of dobutamine/atropine with premature termination of the MR examination (n = 61, 3.6%), including 36 patients with severe chest pain and/or dyspnea, 20 with supraventricular tachycardia, 3 with severe increase in blood pressure > 240/120 mmHg and 2 with non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. None of the patients died or suffered from a myocardial infarction related to DCMR testing. Of the remaining 1575 patients, 43 were lost to follow-up (2.7%). Thus, final analysis was performed on 1532 patients. During DCMR target heart rate was achieved in 1442 patients (94%). Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 provide the clinical baseline characteristics and hemodynamic data of the final patient population according to the result of DCMR, respectively.

Outcomes

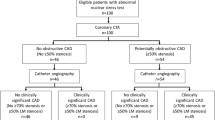

A summary of the outcome data is given in Figure 1. Table 5 provides a summary of events according to DCMR results. In 609 DCMR-pos patients elective invasive angiography was recommended. In 478 out of these 609 patients (78%) invasive angiography was performed within 90 days with 409 patients demonstrating hemodynamically relevant coronary stenoses ≥50% (positive predictive value 86%), see Figure 2 for an example of a DCMR-pos patient. Coronary revascularization was performed in 365 patients. In 69 DCMR-pos patients who underwent invasive angiography without demonstrating coronary stenoses 2 events occurred (event rate 2.9%); these patients had known CAD with moderately reduced LV-function. In 131 patients who did not undergo elective invasive angiography within 90 days 20 events (4 deaths and 16 myocardial infarctions) occurred (event rate 15.3%). The reasons not to perform elective invasive angiography despite a positive DCMR were: patient's refusal (n = 36, 27%; 5 events), few symptoms (n = 20, 15%; 1 event), limited amount of ischemia(n = 16, 12%; mean number of segments with IWMA 1.2 ± 0.4; 1 event), limited amenability to revascularization procedures (e.g. in known chronic coronary vessel occlusion (n = 17, 13%; 3 events)), early occurrence of an event within 90 days (n = 9, 7%) and remained unknown in 33 cases (25%; 1 event).

DCMR in a 56 year old man with exertional dyspnoea and atypical chest pain. He had arterial hypertension and was an active smoker without a prior history of CAD. He was referred for DCMR after a normal exercise ECG and insufficient image quality for a stress echocardiography. DCMR (top and middle) revealed a stress inducible wall motion abnormality of the apical and mid-ventricular anteroseptal segments (white arrows). Invasive angiography (bottom row) demonstrated high grade stenosis of the LAD (white arrow) and intermediate stenoses of the LCX and distal RCA (white arrowheads).

In 923 DCMR-neg patients medical treatment was recommended. No elective invasive angiography was performed within 2 years in 833 out of these 923 patients (90%). Mean follow-up period was 2.1 ± 0.8 years (median: 2.1 years, interquartile range 1.5 to 2.7 years). In this patient subgroup 8 events (3 deaths, 5 myocardial infarctions) occurred (event rate 0.96%; Figure 3). Six out of these 8 patients (75%) had known CAD with prior sustained myocardial infarctions; the mean time to an event was 434 ± 219 days. In 90 DCMR-neg patients elective angiography was performed (10%) with a mean time to invasive angiography of 7 ± 7 months (median: 5 months, interquartile range 0.03 - 13 months), with 56 patients demonstrating coronary stenoses ≥50%. Out of these patients, 34 had single vessel CAD, 16 had double vessel CAD and 6 had triple vessel CAD, no patient had relevant left main disease. Coronary revascularization was performed in 46 patients. In the remaining 34 patients without coronary stenoses no events occurred during follow up. The reasons to perform elective invasive angiography within 2 years of a negative DCMR were: persisting complaints of angina/dyspnea (n = 46; 51%), pathologic findings on another stress test performed within 2 years (n = 21; 23%) or other clinical reasons (e.g. coronary angiography during an electrophysiologic study (n = 23; 26%)).

Table 6 demonstrates cumulative survival rates in patients stratified according to DCMR test results at 1-, 2- and 3-year follow-up intervals; the 3-year event-free survival was 98.5% for patients with negative DCMR and 94% for those with abnormal DCMR.

Segmental extent of ischemia vs. event rate

The mean number of segments with IWMA in the overall population was 1.18 ± 1.73. The number of segments with IWMA in patients with cardiac events was significantly higher compared to those without events (2.1 ± 1.8 vs. 1.2 ± 1.7, respectively; p = 0.003). In particular, patients with an early event occurring <90 days after DCMR showed a significantly higher number of segments with IWMA than those with a late event occurring >90 days after DCMR (3.42 ± 1.62 vs. 1.26 ± 1.41; p = 0.001).

Discussion

The present study addressed the impact of DCMR on clinical management in a large unselected patient population with chest pain syndromes. The main findings are 1) DCMR is applicable in a clinical routine setting with a high success rate and few stressor related complications during a reasonably short examination time of less than 30 minutes, 2) DCMR proved useful as an arbiter for clinical decision making with regard to invasive versus medical treatment in patients with suspected and known CAD, 3) the positive predictive value of DCMR to detect coronary luminal narrowing >50% is high, 4) a positive DCMR is a powerful predictor of future cardiac events, and 5) a negative DCMR test result infers a low risk for subsequent cardiac events (about 1% in the two years after stress testing).

One of the most important clinical questions that non-invasive stress testing has to address is whether patients should be advised to undergo invasive angiography or to continue with medical treatment. As a result of major advances in imaging technology, several diagnostic strategies have become available over the past decades. Although exercise electrocardiography is advocated as a first-line procedure [1], sensitivity may be as low as 45 percent and many patients cannot exercise sufficiently due to poor functional status [17]. In order to determine a patient's most appropriate management multiple tests may be conducted and frequently yield conflicting results. Thus, in a large number of individuals a single imaging test in conjunction with pharmacological stress as the initial strategy may be the most effective approach in patient care. Whereas echocardiography and radionuclide imaging have been evaluated extensively, data on CMR based management strategies are scarce. DCMR has matured into a technically robust method with similarly high values for sensitivity and specificity of ≈ 85% for the detection of myocardial ischemic reactions in the presence of obstructive coronary lesions [12] and has been shown to provide relevant prognostic information [10, 11, 18]. Previous studies focused on the prognostic value of DCMR in low/intermediate versus high risk patient groups as defined by conventional cardiovascular risk factors and reported a relative merit of stress magnetic resonance testing [19]. The design of the present study, however, was unique in that it established the utility of DCMR testing as the sole clinical decision maker in a routine clinical setting: our study attributed DCMR testing an active role in clinical decision making with treatment directed either to a medical or invasive strategy. Consequently, while corroborating the usefulness of DCMR testing, our data closely reflects clinical reality in a tertiary care center setting and as such will be applicable to a similar clinical scenario.

The overall safety profile and frequency of adverse events of DCMR observed in our study are in agreement with previous reports using CMR and other well established methodologies using high dose dobutamine-atropine stress protocols [9, 20]. Results of DCMR were communicated in a timely and definitive manner to the referring physician so that they formed the basis for subsequent clinical decision making.

In our study most patients with a positive DCMR underwent invasive angiography with the intention to perform revascularization. Compared to prior results regarding the diagnostic accuracy of DCMR, this study confirms the high predictive value for the detection of angiographically relevant obstructive coronary stenoses in a population with known or suspected CAD [5, 6]. DCMR-positive patients who did not undergo invasive angiography within 90 days frequently sustained hard cardiac events. Interestingly, the number of patients who sustained early events was relatively high compared to results of the recently published COURAGE and BARI-2D trials which compared invasive vs. conservative management of stable CAD [21, 22]. However, there are certain methodological differences between these trials and our study. First, all patients in the above mentioned trials had to have angiographically proven significant coronary stenosis as an inclusion criterion. In the present study, however, patients were classified with regard to inducible ischemia on the myocardial level. Thus, generalization from these trials to the present patient population is limited. Second, subgroup analyses from COURAGE and BARI-2D showed that outcome is worse with complex CAD and high extent of inducible ischaemia, and that early revascularisation in addition to optimal medical therapy was better than optimal pharmacological therapy alone [3, 23]. Since early revascularization is likely to improve outcome in these high-risk patients, the pivotal role of cardiac imaging as an arbiter in clinical decision making is further corroborated. In our study patients with early events had a significantly greater extent of ischemia suggesting that an early referral to invasive angiography may be advisable in this patient group. Prior studies using SPECT [24] and echocardiography [25] demonstrated that the extent and severity of stress inducible ischemia is associated with a worse outcome, however, similar data using DCMR testing is still limited.

The vast majority of DCMR-negative patients in our study did not undergo invasive angiography during follow-up time. Similar to SPECT imaging and stress echocardiography, a normal DCMR has generally been associated with a hard annual cardiac event rate of ≈ 1% [10, 11, 26, 27]. Data from randomized trials proved that the low rate of cardiac events in patients with negative stress examinations cannot be improved by revascularization as indicated in current guidelines [1, 28]. These patients can be safely treated initially with medical therapy and should only be investigated further if their symptoms cannot be controlled. The impetus for DCMR-driven management has been data from a previously published study dealing with the prognostic value of DCMR and demonstrating a warranty period of two years in case of a negative DCMR test result [11].

In our study 10 percent of the patients with a negative DCMR were subsequently referred for invasive angiography largely owing to recurrent anginal symptoms. In 52 percent revascularization was performed indicating that these patients may have been misclassified as DCMR-neg. The overall "false-negative" rate in our study, however, was low. Previous studies using stress echocardiography have shown that chest pain in the absence of identifiable wall motion abnormalities represents an independent predictor of future cardiac events and should be considered in the interpretation of a normal examination [29]. In addition, it most likely also reflects clinical practice since physicians facing a patient with uncontrolled symptoms are more likely to refer for invasive angiography based on their clinical judgment regardless of the results of prior non-invasive testing. Furthermore, the sensitivity of stress inducible wall motion abnormalities as a marker of ischemia is known to be slightly lower compared to myocardial perfusion imaging techniques. Thus, the addition of perfusion imaging during high dose dobutamine may be helpful in detecting patients with ischemia [4]. Nevertheless, all DCMR-neg patients who underwent invasive angiography without revascularization did not sustain any hard cardiac events supporting the high negative predictive value of the test.

Limitations

Delayed enhancement (DE) images were not acquired for the purpose of this study. The presence and extent of DE has already been demonstrated to carry independent prognostic value [30, 31]. Recently, the combination of CMR vasodilator stress myocardial perfusion and DE was shown to provide complementary prognostic implication for cardiac events [32]. Thus, with regard to prognostication the addition of DE to DCMR may be beneficial in certain patient populations. Visual analysis of invasive angiography by experienced interventional cardiologists was used to determine the degree of coronary luminal narrowing. Quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) is often used as a reference standard in clinical trials, but its usage during routine coronary angiography is rather limited though it may be performed to assist planning of a revascularization procedure. The aim of the present study, however, was to define the role of DCMR testing within a widely seen clinical scenario.

Conclusions

In our study we demonstrated that a DCMR based management strategy can be used as a reliable gatekeeper to invasive procedures or to substantiate the decision to proceed with medical treatment. Thus, DCMR provides a directive for appropriate and profound clinical management of patients with suspected and known CAD.

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

Coronary Artery Disease

- CMR:

-

Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

- DCMR:

-

Dobutamine cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance

- EF:

-

Ejection Fraction

- LV:

-

Left Ventricle

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- IWMA:

-

Inducible Wall Motion Abnormality.

References

Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, Ferguson TB, Fihn SD, Fraker TD, Gardin JM, O'Rourke RA, Pasternak RC, Williams SV, Gibbons RJ, Alpert JS, Antman EM, Hiratzka LF, Fuster V, Faxon DP, Gregoratos G, Jacobs AK, Smith SC: ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation. 2003, 107: 149-158. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047041.66447.29.

Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM, Poon M, Hendel RC, Carr JC, Gerstad NA, Gillam LD, Hodgson JM, Kim RJ, Kramer CM, Lesser JR, Martin ET, Messer JV, Redberg RF, Rubin GD, Rumsfeld JS, Taylor AJ, Weigold WG, Woodard PK, Brindis RG, Hendel RC, Douglas PS, Peterson ED, Wolk MJ, Allen JM, Patel MR: ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 48: 1475-1497. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.003.

Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, Mancini GB, Hayes SW, Hartigan PM, Weintraub WS, O'Rourke RA, Dada M, Spertus JA, Chaitman BR, Friedman J, Slomka P, Heller GV, Germano G, Gosselin G, Berger P, Kostuk WJ, Schwartz RG, Knudtson M, Veledar E, Bates ER, McCallister B, Teo KK, Boden WE: Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008, 117: 1283-1291. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963.

Gebker R, Jahnke C, Manka R, Hamdan A, Schnackenburg B, Fleck E, Paetsch I: Additional Value of Myocardial Perfusion Imaging During Dobutamine Stress Magnetic Resonance for the Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008, 1: 122-130. 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.779108.

Hundley WG, Hamilton CA, Thomas MS, Herrington DM, Salido TB, Kitzman DW, Little WC, Link KM: Utility of fast cine magnetic resonance imaging and display for the detection of myocardial ischemia in patients not well suited for second harmonic stress echocardiography. Circulation. 1999, 100: 1697-1702.

Nagel E, Lehmkuhl HB, Bocksch W, Klein C, Vogel U, Frantz E, Ellmer A, Dreysse S, Fleck E: Noninvasive diagnosis of ischemia-induced wall motion abnormalities with the use of high-dose dobutamine stress MRI: comparison with dobutamine stress echocardiography. Circulation. 1999, 99: 763-770.

Paetsch I, Jahnke C, Fleck E, Nagel E: Current clinical applications of stress wall motion analysis with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2005, 6: 317-326. 10.1016/j.euje.2004.12.008.

Pennell DJ, Sechtem UP, Higgins CB, Manning WJ, Pohost GM, Rademakers FE, van Rossum AC, Shaw LJ, Yucel EK: Clinical indications for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR): Consensus Panel report. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004, 6: 727-765. 10.1081/JCMR-200038581.

Wahl A, Paetsch I, Gollesch A, Roethemeyer S, Foell D, Gebker R, Langreck H, Klein C, Fleck E, Nagel E: Safety and feasibility of high-dose dobutamine-atropine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance for diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia: experience in 1000 consecutive cases. Eur Heart J. 2004, 25: 1230-1236. 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.018.

Hundley WG, Morgan TM, Neagle CM, Hamilton CA, Rerkpattanapipat P, Link KM: Magnetic resonance imaging determination of cardiac prognosis. Circulation. 2002, 106: 2328-2333. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000036017.46437.02.

Jahnke C, Nagel E, Gebker R, Kokocinski T, Kelle S, Manka R, Fleck E, Paetsch I: Prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance stress tests: adenosine stress perfusion and dobutamine stress wall motion imaging. Circulation. 2007, 115: 1769-1776. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.652016.

Nandalur KR, Dwamena BA, Choudhri AF, Nandalur MR, Carlos RC: Diagnostic performance of stress cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50: 1343-1353. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.030.

Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB: Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998, 97: 1837-1847.

Nagel E, Lorenz C, Baer F, Hundley WG, Wilke N, Neubauer S, Sechtem U, van der Wall E, Pettigrew R, de Roos A, Fleck E, van Rossum A, Pennell DJ, Wickline S: Stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance: consensus panel report. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2001, 3: 267-281. 10.1081/JCMR-100107475.

Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, Pennell DJ, Rumberger JA, Ryan T, Verani MS: Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002, 105: 539-542. 10.1161/hc0402.102975.

Thiele H, Paetsch I, Schnackenburg B, Bornstedt A, Grebe O, Wellnhofer E, Schuler G, Fleck E, Nagel E: Improved accuracy of quantitative assessment of left ventricular volume and ejection fraction by geometric models with steady-state free precession. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2002, 4: 327-339. 10.1081/JCMR-120013298.

Froelicher VF, Lehmann KG, Thomas R, Goldman S, Morrison D, Edson R, Lavori P, Myers J, Dennis C, Shabetai R, Do D, Froning J: The electrocardiographic exercise test in a population with reduced workup bias: diagnostic performance, computerized interpretation, and multivariable prediction. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study in Health Services #016 (QUEXTA) Study Group. Quantitative Exercise Testing and Angiography. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 128: 965-974.

Dall'Armellina E, Morgan TM, Mandapaka S, Ntim W, Carr JJ, Hamilton CA, Hoyle J, Clark H, Clark P, Link KM, Case D, Hundley WG: Prediction of cardiac events in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction with dobutamine cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of wall motion score index. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52: 279-286. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.025.

Korosoglou G, Elhmidi Y, Steen H, Schellberg D, Riedle N, Ahrens J, Lehrke S, Merten C, Lossnitzer D, Radeleff J, Zugck C, Giannitsis E, Katus HA: Prognostic value of high-dose dobutamine stress magnetic resonance imaging in 1,493 consecutive patients: assessment of myocardial wall motion and perfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 56: 1225-1234.

Geleijnse ML, Fioretti PM, Roelandt JR: Methodology, feasibility, safety and diagnostic accuracy of dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 30: 595-606. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00206-4.

Boden WE, O'Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GB, Weintraub WS: Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 1503-1516. 10.1056/NEJMoa070829.

Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, Hardison RM, Kelsey SF, MacGregor JM, Orchard TJ, Chaitman BR, Genuth SM, Goldberg SH, Hlatky MA, Jones TL, Molitch ME, Nesto RW, Sako EY, Sobel BE: A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360: 2503-2515.

Chaitman BR, Hardison RM, Adler D, Gebhart S, Grogan M, Ocampo S, Sopko G, Ramires JA, Schneider D, Frye RL: The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes randomized trial of different treatment strategies in type 2 diabetes mellitus with stable ischemic heart disease: impact of treatment strategy on cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009, 120: 2529-2540. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913111.

Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS: Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003, 107: 2900-2907. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41.

Marwick TH, Case C, Sawada S, Rimmerman C, Brenneman P, Kovacs R, Short L, Lauer M: Prediction of mortality using dobutamine echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 37: 754-760. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01191-8.

Beller GA, Zaret BL: Contributions of nuclear cardiology to diagnosis and prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2000, 101: 1465-1478.

Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, Beller GA, Bierman FZ, Davis JL, Douglas PS, Faxon DP, Gillam LD, Kimball TR, Kussmaul WG, Pearlman AS, Philbrick JT, Rakowski H, Thys DM: ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography--summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 42: 954-970. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)01065-9.

Yusuf S, Zucker D, Peduzzi P, Fisher LD, Takaro T, Kennedy JW, Davis K, Killip T, Passamani E, Norris R, et al: Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet. 1994, 344: 563-570. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91963-1.

McCully RB, Roger VL, Mahoney DW, Karon BL, Oh JK, Miller FA, Seward JB, Pellikka PA: Outcome after normal exercise echocardiography and predictors of subsequent cardiac events: follow-up of 1,325 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998, 31: 144-149.

Cheong BY, Muthupillai R, Wilson JM, Sung A, Huber S, Amin S, Elayda MA, Lee VV, Flamm SD: Prognostic significance of delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging: survival of 857 patients with and without left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2009, 120: 2069-2076. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852517.

Yan AT, Shayne AJ, Brown KA, Gupta SN, Chan CW, Luu TM, Di Carli MF, Reynolds HG, Stevenson WG, Kwong RY: Characterization of the peri-infarct zone by contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is a powerful predictor of post-myocardial infarction mortality. Circulation. 2006, 114: 32-39. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613414.

Steel K, Broderick R, Gandla V, Larose E, Resnic F, Jerosch-Herold M, Brown KA, Kwong RY: Complementary prognostic values of stress myocardial perfusion and late gadolinium enhancement imaging by cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2009, 120: 1390-1400. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812503.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge radiographers at the German Heart Institute Gudrun Grosser, Corinna Else, and Janina Dentzer for high-quality CMR examinations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Bernhard Schnackenburg is an employee of Philips Health Care; Hamburg, Germany.

Authors' contributions

RG carried out CMR examinations, collected follow up information and drafted the manuscript. CJ carried out CMR examinations and helped with the revision of the manuscript. RM carried out CMR examinations. TH carried out CMR examinations and collected follow up information. BS participated in the study design and helped with the revision of the manuscript. SK carried out CMR examinations. CK carried out and analyzed invasive angiography. EF participated in the study design and helped with the revision of the manuscript. IP conceived of the study, carried out CMR examinations and helped with the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebker, R., Jahnke, C., Manka, R. et al. The role of dobutamine stress cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the clinical management of patients with suspected and known coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 13, 46 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-13-46

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-13-46