Abstract

Background

Modernisation and urbanisation have led to lifestyle changes and increasing risks for chronic diseases in China. Physical activity and sedentary behaviours among rural populations need to be better understood, as the rural areas are undergoing rapid transitions. This study assessed levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviours of farming and non-farming adults in rural Suixi, described activity differences between farming and non-farming seasons, and examined correlates of leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and TV viewing.

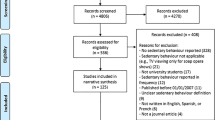

Methods

A random sample of rural adults (n = 287) in Suixi County, Guangdong, China were surveyed in 2009 by trained interviewers. Questionnaires assessed multiple physical activities and sedentary behaviours, and their correlates. Analysis of covariance compared activity patterns across occupations, and multiple logistic regressions assessed correlates of LTPA and TV viewing. Quantitative data analyses were followed by community consultation for validation and interpretation of findings.

Results

Activity patterns differed by occupation. Farmers were more active through their work than other occupations, but were less active and more sedentary during the non-farming season than the farming season. Rural adults in Suixi generally had a low level of LTPA and a high level of TV viewing. Marital status, household size, social modelling for LTPA and owning sports equipment were significantly associated with LTPA but not with TV time. Most findings were validated through community consultation.

Conclusions

For chronic disease prevention, attention should be paid to the currently decreasing occupational physical activity and increasing sedentary behaviours in rural China. Community and socially-based initiatives provide opportunities to promote LTPA and prevent further increase in sedentary behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is an emerging epidemic worldwide. In the last few decades, rapid urbanisation and economic growth in China have led to increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity [1]. China is in an epidemiological transition defined by positive energy balance and mounting prevalence of non-communicable diseases [2, 3]. In 2000, 25.6% of the urban and 17.3% of the rural populations were overweight or obese, compared to 12.2% and 7.7% in 1989 [1].

In addition to a dramatic increase in energy intake [4, 5], China has experienced a noticeable decrease in energy expenditure in both urban and rural areas [6]. Decreases in physical activity have been reported for several domains, including occupation, transportation and household activity [7]. In China, occupation has been a major source of physical activity [8]. According to the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), between 1991 and 2000, energy expenditure from occupational physical activity decreased by 22% among men and 24% among women, and the decrease contributed to the increase in body weight [9]. During the same nine-year period, energy expenditure from household physical activity decreased by 57% among men and 51% among women [9]. A similar trend was found with transportation physical activity [6]. As the Chinese society moves toward modern inactive lifestyles [7], leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) remains low [10]. Population survey data from 2006 found that only 13% of Chinese men and 8% of women engaged in any LTPA [6]. Although population data have shown a slight increase in LTPA, the increase has not been sufficient to compensate for declines in occupational and household activity [6].

Sedentary behaviour (too much sitting) is distinct from too little physical activity. Multiple studies have concluded that sedentary time is an independent risk factor for metabolic risk and chronic diseases [11, 12]. TV viewing particularly has been associated with increased risks for overweight/obesity [13, 14], diabetes [13, 15], and metabolic syndrome [16, 17]. Sedentary behaviours are understudied in China. One survey study in urban Qingdao found that adults spent an average of 3.2 sedentary hours per day watching TV, reading, or using a computer during non-working time [18]. Excess sedentary time is a public health concern in China given high rates of TV and personal computer ownership, particularly among urban residents [1]. No study could be found that examined sedentary behaviours in rural China.

In China, rural residents are currently more physically active and less obese than their urban counterparts [19]. However, a national study found a greater decrease in physical activity in rural areas than in urban areas over a recent ten-year period [20]. The current study was conducted in Suixi County, Guangdong, China, an area that has experienced farming-to-business shifts and some degree of economic modernisation, in common with many rural areas in China. Study objectives are: to assess levels of physical activity and sedentary behaviours of farming and non-farming adults in rural Suixi; to describe different activity patterns during farming and non-farming seasons; and to examine factors associated with LTPA and TV viewing.

Methods

Population and sampling

Participants were rural adults in Suixi County, Guangdong, China. The Suixi County population has been documented to be some 1.03 million (47% female), rural (>90% rural residents), and 77% of the working population are employed in farming or farming-related business/industry [21]. Households were randomly selected based on village, street, block, and house numbers. A list of 70 villages was enumerated based on information from the local government website http://cwgk.zhanjiang.gov.cn/. Ten villages were selected randomly. In each selected village, a map was obtained through local sources, and streets and blocks were randomly selected accordingly. In each selected household, the adult with the most recent birthday was invited to participate. If no one was home during the first visit, interviewers would return on the next two consecutive days for interview attempts. Inclusion criteria were 18 years or older and having lived in the village for at least three years. Written informed consent was obtained and small monetary incentives were provided. The San Diego State University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

In July 2009, 454 local residents were contacted and 287 participated in the survey (63% participation rate) during 14 days of data collection, which took place on both week days and weekend days depending on participants' availability. Interviewers kept notes of the gender and estimated age (young, middle-age, old) of each individual they approached and found no differential refusal rates by gender or age. Participants ranged from 18 to 82 years of age (mean = 40, SD = 16), 53% were women, 73% were married, and 65% completed middle school (nine-year mandatory education in China). About 32% were farmers, 18% were employed in non-farming occupations, 23% were self-employed shop keepers, and 26% were unemployed. The unemployed category included those who were retired, those not actively seeking employment, and those between jobs; the unemployed were usually not financially independent and were taken care of by families. It was possible, however, that they worked episodically for money.

Procedures

Face-to-face interviews were conducted by trained interviewers, who were local college students speaking Mandarin and at least one of the two local dialects (Cantonese, Leizhou Dialect). Interviews were conducted in participant's preferred language. About 62% of interviews were conducted in Cantonese, 30% in Leizhou Dialect, and 8% in Mandarin. Verbal explanation and visual aids were provided if participants had problems understanding certain questions. For quality-control purposes, two interviewers were paired for each interview: one asked questions and wrote down answers while the other checked progress with the interview protocol and the accuracy of recorded answers.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was developed from existing measures, informant interviews and focus groups. An iterative process of questionnaire development, informant interviews/focus groups, and questionnaire revision was used. Chinese-translated items were back-translated to English to compare with original questions. The final questionnaire was shortened, simplified, and was considered culturally appropriate by focus group participants, informants and interviewers.

Measurement

Physical activity

Physical activity was measured in three domains: occupation, household, and leisure-time, using questions modelled after the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) [22]. Occupational moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was defined as "activity that causes at least small increases in breathing and heart rate" through occupation; examples were provided such as lifting loads, digging, or farm work. Household physical activity was defined as any housework that involves physical activity, such as cleaning and maintaining the yard. Leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) was defined as any physical activity for the purpose of recreation and/or fitness, such as leisure walking, playing basketball, and martial arts. For each type of activity, two questions were asked about the number of days and hours/minutes per day in a typical week. A weekly time for each activity was calculated from the two questions.

Sedentary behaviour

This was defined as "sitting or reclining". Questions were modelled after GPAQ [22] regarding the days per typical week and time per day spent on each of the sedentary behaviours. Specific behaviours listed were suggested by focus groups as being "the most common sedentary activities" in rural Zhanjiang. These included TV viewing (when this was the primary behaviour and did not include doing other non-sedentary activities while TV was switched on [23]), recreational computer use (prevalent among young people), sitting chatting, playing Mahjong (a popular board game), and driving/riding a car/bus.

Seasonality of activity

Activity patterns of farmers are seasonal. Farmers do moderate-to-high-intensity, long-hour planting and harvesting activities during the farming season and less-intense field maintenance during the non-farming season. In the study sample, the length of the farming season ranged from two weeks to six months, depending on the type of crops under cultivation. To capture seasonality of activities, those in the farmer subsample was asked to estimate the length of farming season every year, and to recall physical activity and sedentary behaviours separately for a typical week during the farming and non-farming seasons.

Neighbourhood characteristics

The Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS) [24] aesthetics and safety subscales were translated and tested in formative interviews and focus groups. Based on their feedback, several items were deleted due to lack of relevance or appropriateness in rural China (e.g. crosswalks, posted speed limits). Items were simplified in language and response categories were reduced from four to two ("agree" vs. "disagree"). The final safety subscale included six items concerning walking/biking safety, crime rates, day-time safety, night-time safety, and street lights. The aesthetics subscale included three items regarding sidewalk condition, trees/shades, and cleanness.

Social modelling

Participants were asked "how many of your family members participate in physical activity for recreation or exercise?" Parallel questions were asked about friends and neighbours. Response options ranged from "none" (1) to "all" (5). Due to a large proportion of the "none" response, variables were dichotomized into "none" and "any".

Data analyses

Activity data were examined for distribution and outliers. Outliers were identified and recoded to the 95th percentile of the distribution. Most of the physical activity and sedentary behaviour variables were highly skewed, and were therefore log transformed.

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) compared hours of physical activity and sedentary behaviours across occupations, adjusting for age as a covariate, and separately for men and women. Additional ANCOVA compared hours of activity between men and women for each employment category. For farmers, weighted physical activity hours were calculated based on the lengths of farming/non-farming seasons and activities in each season.

Participation in LTPA was dichotomized as "none" and "any" due to a large proportion of zero values (66%) and the lack of variance in LTPA time for those who reported any (around 80% reported an hour or less per week). TV time was median-split at 12 hours/week. χ2 tests and t-tests examined bivariate associations between independent variables and dependent variables (LTPA, TV time).Variables with a significance level of p < 0.05 were included in the multiple logistic regression model. Analyses were first conducted for men and women separately, and then combined if similar associations were observed for both genders. Social-modelling variables were summed as an overall index in the logistic regression model.

Informant consultation

Member checking [25], a qualitative research method, was used to obtain community feedback and to validate findings. Informants (n = 10) were rural adults who did not participate in the previous survey, and were randomly selected from the villages where the survey interviews were conducted. Key findings from quantitative data analyses were abstracted into simple sentences and graphs, and were presented to informants both individually and as a group. Informants were encouraged to provide feedback and interpretation of findings, which were audio taped and transcribed.

Results

Descriptive statistics of physical activity and sedentary behaviours

As Table 1 shows, farmers had more occupational physical activity compared to other groups. Farmers and those who were self-employed had more TV viewing time than did non-farming, and unemployed respondents. Farmers reported almost no recreational computer use, and more sitting chatting time compared to other occupations (statistically significant only among women).

In general, men and women showed similar activity patterns across occupation categories. Geometric means for different types of activity were similar between genders. Exceptions were that women spent much more time on household physical activity and less time on motorized transportation.

Seasonal activity patterns for farmers

Compared to the farming season, farmers had significantly less occupational physical activity (geometric mean 6.79 vs. 19.54 hr/week, p < 0.01) and more TV viewing (15.54 vs. 10.45, p < 0.05) during the non-farming season (Figure 1). LTPA level was low for both the farming and non-farming seasons (0.22 vs. 0.33, p = 0.340).

Correlates of leisure-time physical activity and TV time

Bivariate analyses (Table 2) showed higher participation in LTPA among those who were younger, men, single, middle school graduated, living in a smaller household, employed in non-farming occupations or not employed, having sports equipment in the home, living in a safer neighbourhood, and having family, friends, and neighbours who exercised regularly.

In the multiple logistic regression model (Table 3), those who were married had less than one third the odds of participating in LTPA compared to those who were single. An additional person living in the household was associated with a 21% decrease in odds of LTPA. Those who had sports equipment in the home had twice the odds of participating in LTPA. A one-unit increase in the social modelling scale was associated with a more than two-fold increase in the odds of LTPA. Similar patterns of associations were found among men and women.

Gender-stratified and combined bivariate analyses and multiple logistic regressions suggested that none of the correlates tested was significantly associated with TV viewing time; therefore, no logistic regression model is presented.

Discussion

This study in rural Suixi found differences in physical activity and sedentary behaviour by occupation. Farmers had significantly more occupational physical activity compared to their non-farming counterparts, however, they appeared to substitute farming activities with sedentary behaviours (primarily TV viewing) during non-farming seasons. Based on this pattern, one may expect further decreases in occupational physical activity as a result of fewer farming-related occupations, less labour-intensive farm work, and shorter farming seasons. Without compensating forms of physical activity or reduction of TV time, this pattern suggests future increases in overweight/obesity and associated chronic diseases.

The prevalence of LTPA was low in the study sample, which was consistent with findings from previous studies [6, 10, 19]. Correlates of LTPA were explored. After adjusting for other demographic characteristics and environmental variables, those in our study were more likely to participate in LTPA if they were unmarried, living in a smaller household, having sports equipment in the home and if their family, friends, or neighbours participated in LTPA.

The strongest correlate of LTPA was social modelling. During the "member checking" phase of the study, informants strongly agreed with this finding. A woman informant stated, "We are in a very collective society and nobody exercises alone." Other informants confirmed that families, friends, and neighbours in their communities were closely connected (i.e., "The social circle is small here. If one person goes out for a walk, immediately others will notice and probably will follow. They can chat while walking.") Studies in western countries have suggested that seeing other people exercise was associated with individuals' own participation in LTPA, possibly through modelling and prompting [26–28]. In the context of rural China, exercising with others may provide additional and possibly essential social reinforcement. Social support and group activity interventions are effective in Western countries [29], and they may be even more effective in China, but this remains to be demonstrated.

Another finding was that those who had sports equipment in the home had twice the odds of engaging in LTPA. In a cross-sectional study, such a finding should be interpreted with caution, since it is possible that those who had already been active would be more likely to obtain such equipment. Informants suggested that home equipment was only half of the equation if access to exercise facilities and localities was limited. For example, a young man stated "It is true that I am more active because I have a basketball, but I play in streets where it is not safe. I would have played a lot more if there was a basketball court around." Although the Chinese government has implemented the "Sports for All" program to expand relevant facilities and infrastructure [30], rural residents still have limited access to such facilities, as demonstrated by one informant's comment, "Sometimes we have to travel for hours to a bigger town for sports. We do not have anything here in our village." In this study sample, adults who were married or who were living in a larger household were less active. This may be a result of related lifestyles and competing priorities of other household activities. An informant said: "We have to travel so far for any activity. If one is married and has children (like me), how can s/he have time for any recreation?"

TV viewing was the major sedentary behaviour. The median TV time was 12 hours per week, and 39% watched TV for 14 hours or more. This is comparable to TV viewing time reported by adults in the US [31, 32]. A woman informant described the "common" lifestyle in her village: "People in my village tend to turn on TV immediately after meals, and then they rest (sitting or lying down) for one hour after lunch, and another hour after dinner." In the current sample, 96% of participants had a TV set in the home, indicating substantial influences from modernisation. Although computers were not as common (23% participants had a computer at home), it is reasonable to postulate that as computer ownership increases, screen time sedentary behaviour may further increase in rural China.

None of the correlates of LTPA was significantly associated with TV time. This finding was similar to a previous study, in which environmental variables that facilitated physical activity were not related to TV time [33]. Furthermore, no association was found between TV time and LTPA in the current sample (Table 2). This suggests that TV viewing may be a behaviour that is independent of physical activity in rural Suixi [11].

A major strength of the study was using community participation to enhance the design, survey administration and results interpretation. These procedures improved the cultural relevance of research questions, qualitatively validated research findings, and provided interpretations that extended quantitative results. Although a small sample from one county in southern China limits generalizability, and a cross-sectional study cannot establish causality, these findings provide insights to guide future larger-scale and prospective studies that employ objective measures of the environment, physical activity, multiple sedentary behaviours (including sleeping) [34], and health outcomes. Future studies should assess additional aspects of the built and social environments and explore variables related to sedentary behaviours, especially TV viewing.

Conclusions

The current study, together with previous studies on the consequences of modernisation in China [6, 9, 10, 35], suggests that if no effective public health actions or social and environmental initiatives are implemented, further decreases in physical activity and increases in sedentary behaviours leading to higher risk of major chronic diseases are likely, as a by-product of the economic development, modernisation, and urbanisation in China.

In rapid social and epidemiological transitions, Chinese central and local governments are in the position of making health-promoting changes and taking preventive measures through city planning initiatives, infrastructure building, and land-use development to provide activity environments [36]. Physical activity programs should be implemented in rural China targeting multiple levels of influences [37]. Interventions to improve accessibility of recreational facilities and to promote physical activity as a social behaviour may be culturally tailored.

References

Wang H, Du S, Zhai F, Popkin BM: Trends in the distribution of body mass index among Chinese adults, aged 20-45 years (1989-2000). Int J Obes (Lond). 2007, 31 (2): 272-278. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803416.

Du S, Lu B, Zhai F, Popkin BM: A new stage of the nutrition transition in China. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5 (1A): 169-174.

Popkin BM, Horton S, Kim S, Mahal A, Shuigao J: Trends in diet, nutritional status, and diet-related noncommunicable diseases in China and India: the economic costs of the nutrition transition. Nutr Rev. 2001, 59 (12): 379-90.

Popkin BM, Du S: Dynamics of the nutrition transition toward the animal foods sector in China and its implications: a worried perspective. J Nutr. 2003, 133 (Suppl 2): 3898-3906.

Zhai F, Wang H, Du S, He Y, Wang Z, Ge K, Popkin BM: Lifespan nutrition and changing socio-economic conditions in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007, 16: 374-382.

Ng SW, Norton EC, Popkin BM: Why have physical activity levels declined among Chinese adults? Findings from the 1991-2006 China Health and Nutrition Surveys. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 68 (7): 1305-1314. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.035.

Bauman A, Allman-Farinelli M, Huxley R, James WPT: Leisure-time physical activity alone may not be a sufficient public health approach to prevent obesity--a focus on China. Obes Rev. 2008, 9 (Suppl 1): 119-126.

Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM: Weight gain and its predictors in Chinese adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001, 25 (7): 1079-1086. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801651.

Monda KL, Adair LS, Zhai F, Popkin BM: Longitudinal relationships between occupation and domestic physical activity patterns and body weight in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008, 62 (11): 1318-1325. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602849.

Monda KL, Gordon-Larsen P, Stevens J, Popkin BM: China's transition: the effect of rapid urbanization on adult occupational physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2007, 64 (4): 858-870. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.019.

Healy GN, Wijndaele K, Dunstan DW, Shaw JE, Salmon J, Zimmet PZ, Owen N: Objectively measured sedentary time, physical activity, and metabolic risk: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Diabetes Care. 2008, 31 (2): 369-371.

Owen N, Bauman A, Brown W: Too much sitting: a novel and important predictor of chronic disease risk?. Br J Sports Med. 2009, 43 (2): 81-83.

Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE: Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA. 2003, 289 (14): 1785-1791. 10.1001/jama.289.14.1785.

Salmon J, Bauman A, Crawford D, Timperio A, Owen N: The association between television viewing and overweight among Australian adults participating in varying levels of leisure-time physical activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000, 24 (5): 600-606. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801203.

Hu FB, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rimm EB: Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Arch Intern Med. 2001, 161 (12): 1542-1548. 10.1001/archinte.161.12.1542.

Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Owen N, Armstrong T, Zimmet PZ, Welborn TA, Cameron AJ, Dwyer T, Jolley D, Shaw JE: Associations of TV viewing and physical activity with the metabolic syndrome in Australian adults. Diabetologia. 2005, 48 (11): 2254-2261. 10.1007/s00125-005-1963-4.

Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N: Television time and continuous metabolic risk in physically active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008, 40: 639-645. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181607421.

Chen X, Pang Z, Li K: Dietary fat, sedentary behaviors and the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Qingdao adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009, 19 (1): 27-34. 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.01.010.

Muntner P, Gu D, Wildman RP, Chen J, Qan W, Whelton PK, He J: Prevalence of physical activity among Chinese adults: results from the International Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease in Asia. Am J Public Health. 2005, 95 (9): 1631-1636. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044743.

Xie G, Mai J, Zhao L, Liu X: Physical activity status of working time and its change over a ten-year period in Beijing and Guangzhou populations. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2008, 37 (1): 33-6.

University of Michigan-China Data Center. [http://chinadatacenter.org/]

Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T: Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009, 6: 790-804.

Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Balkau B, Magliano DJ, Cameron AJ, Zimmet PZ, Owen N: Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation. 2010, 121 (3): 384-391. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894824.

Cerin E, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD: Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale: Validity and development of a short form. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006, 38: 1682-1691. 10.1249/01.mss.0000227639.83607.4d.

Yanow D, Schwartz-Shea P: Interpretation and method: Empirical research methods and the interpretive turn. 2006, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc

Ainsworth BE, Wilcox S, Thompson WW, Richter DL, Henderson KA: Personal, social, and physical environmental correlates of physical activity in African-American women in South Carolina. Am J Prev Med. 2003, 25 (3 Suppl 1): 23-29.

King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC: Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of U.S. middle-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychol. 2000, 19 (4): 354-364.

Mota J, Almeida M, Santos P, Ribeiro JC: Perceived neighborhood environments and physical activity in adolescents. Prev Med. 2005, 41 (5-6): 834-836. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.07.012.

Kahn EB, Ramsey LT, Brownson RC, Heath GW, Howze EH, Powell KE, Stone EJ, Rajab MW, Corso P: The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2002, 22 (4 Suppl): 73-107.

Chen JD: National policies promoting better nutrition, physical fitness and sports for all in China. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1997, 81: 114-121.

Bowman SA: Television-viewing characteristics of adults: correlations to eating practices and overweight and health status. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006, 3 (2): A38.

King AC, Goldberg JH, Salmon J, Owen N, Dunstan D, Weber D, Doyle C, Robinson TN: Identifying subgroups of U.S. adults at risk for prolonged television viewing to inform program development. Am J Prev Med. 2010, 38 (1): 17-26. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.032.

Williams CD, Sallis JF, Calfas KJ, Burke R: Psychosocial and demographic correlates of television viewing. Am J Health Promot. 1999, 13 (4): 207-214.

Tremblay MS, Esliger DW, Tremblay A, Colley R: Incidental movement, lifestyle-embedded activity and sleep: new frontiers in physical activity assessment. Can J Public Health. 2007, 98 (S2): S208-217.

Popkin BM: Will China's nutrition transition overwhelm its health care system and slow economic growth?. Health Aff. 2008, 27 (4): 1064-1076. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1064.

Sallis JF, Bowles HR, Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Bull FC, Craig CL, Sjöström M, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Lefevre J, Matsudo V, Matsudo S, Macfarlane DJ, Gomez LF, Inoue S, Murase N, Volbekiene V, McLean G, Carr H, Heggebo LK, Tomten H, Bergman P: Neighborhood environments and physical activity among adults in 11 countries. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36 (6): 484-490. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.031.

Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB: Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. 2008, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 4

Acknowledgements and Funding

The authors wish to thank the following students from Zhanjiang Normal University for their invaluable help in the project: Caihong Shen, Fenglian Zeng, Xiaoting Zhang, Qi Yuan, Jianhua Peng, Rihui Wu, Yueyu Xie, & Shangru Ke.

This study was supported by grant HL066307 to Dr. Melbourne F. Hovell from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood institute, National Institutes of Health, and by discretionary funds from Drs. Melbourne F. Hovell and James F. Sallis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

DD designed the study, developed research plans and instrument, conducted focus group interviews, data collection, analyses, community consultation, and drafted the manuscript. MFH and JFS provided guidance and advice throughout the entire study and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. JD coordinated the involvement of Zhanjiang Normal University, provided input to study design, organized trainings, and supervised interviewers. MZ and HH organized focus group interviews, provided input to instrument development, and conducted interviews. NO provided guidance on the focus and organisation of content, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, D., Sallis, J.F., Hovell, M.F. et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviours among rural adults in suixi, china: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8, 37 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-37

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-37