Abstract

Background

Understanding the correlates of dietary intake is necessary in order to effectively promote healthy dietary behavior among children and adolescents. A literature review was conducted on the correlates of the following categories of dietary intake in children and adolescents: Fruit, Juice and Vegetable Consumption, Fat in Diet, Total Energy Intake, Sugar Snacking, Sweetened Beverage Consumption, Dietary Fiber, Other Healthy Dietary Consumption, and Other Less Healthy Dietary Consumption in children and adolescents.

Methods

Cross-sectional and prospective studies were identified from PubMed, PsycINFO and PsycArticles by using a combination of search terms. Quantitative research examining determinants of dietary intake among children and adolescents aged 3–18 years were included. The selection and review process yielded information on country, study design, population, instrument used for measuring intake, and quality of research study.

Results

Seventy-seven articles were included. Many potential correlates have been studied among children and adolescents. However, for many hypothesized correlates substantial evidence is lacking due to a dearth of research. The correlates best supported by the literature are: perceived modeling, dietary intentions, norms, liking and preferences. Perceived modeling and dietary intentions have the most consistent and positive associations with eating behavior. Norms, liking, and preferences were also consistently and positively related to eating behavior in children and adolescents. Availability, knowledge, outcome expectations, self-efficacy and social support did not show consistent relationships across dietary outcomes.

Conclusion

This review examined the correlates of various dietary intake; Fruit, Juice and Vegetable Consumption, Fat in Diet, Total Energy Intake, Sugar Snacking, Sweetened Beverage Consumption, Dietary Fiber, Other Healthy Dietary Consumption, and Other Less Healthy Dietary Consumption in cross-sectional and prospective studies for children and adolescents. The correlates most consistently supported by evidence were perceived modeling, dietary intentions, norms, liking and preferences. More prospective studies on the psychosocial determinants of eating behavior using broader theoretical perspectives should be examined in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diets high in fat and sugar, and low in fruit, vegetables and fiber, have been related to obesity, risk for type 2 diabetes [1, 2], cardiovascular disease [3–6], and some cancers [7, 8]. Dietary habits tend to form early and track from childhood into adulthood [9, 10]. Therefore, the promotion of healthy diet in children and adolescents is a priority to help promote health and well-being, prevent future disease, and reduce the current epidemic of pediatric obesity [11].

To develop effective dietary interventions for children and adolescents, it is necessary to understand the factors that determine eating behavior in these populations. Research has repeatedly shown that theory-based interventions that are guided by relevant behavioral theories are more likely to significantly impact dietary behaviors in youth [11–13]. Theory-based research is fundamental to the understanding of health behaviors by providing a framework by which to examine the relationships among constructs [11, 14–16], to assess the impact of the various constructs [11, 14, 17], and to delineate factors and determinants to be studied [11, 15, 16, 18]. Theory adds coherence and effectiveness to research by identifying facilitating situations and relevant processes and guiding timing and sequencing of events [11, 15, 16, 18]. A good theory indicates methods of intervention and evaluation [11, 15, 16, 18].

The current review represents an updated comprehensive review of psychosocial correlates of a broad range of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Earlier reviews in youth and adults have focused mainly on determinants of fruit and vegetable intake [19, 20], healthy eating [21, 22], or environmental factors related to diet [23, 24]. For instance, Rasmussen et al [19] recently published a review that examined a broad range of correlates, including psychosocial and environmental correlates, focused exclusively on fruit and vegetable intake. However, recent science has shown that sugar and fiber intake is closely related to insulin dynamics and body composition [25, 26]. Sugar sweetened beverage intake is associated with weight gain [27]. Dietary fat has also been shown to have an effect on body fat and on total energy intake [28]. Psychosocial determinants that predict dietary behavior in children and adolescents are not necessarily the same as those that predict dietary behavior in adult populations [11]. Psychosocial as well as dietary intake measures that have been validated in adults are not necessarily valid in younger populations [11]. Some research has suggested that less cognitively-based, more emotionally-based determinants drive adolescent health-related behavior [11, 29]. For adolescents and young adults, the immediate satisfaction of psychological needs and adherence to the individual's personal meanings have been shown to be strong motivators and determinants of health behaviors in this age group [30, 31]. Research has shown that these age-related differences may be related to neurological development [32].

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of psychosocial correlates of dietary behaviors in children and adolescents, and included not only fruit and vegetable consumption, but also fat intake, total energy intake, sugar snacking, sweetened beverage consumption, fiber intake, other healthy dietary consumption, and other less healthy dietary consumption. Psychosocial factors are constructs defined here as referring to internal processes in interaction with (but not including) the social environment, and is often used in the context of psychosocial interventions that point towards solutions for individual challenges within the context of the social environment. Socio-demographic and environmental correlates were not reviewed. Our review focused on addressing the following two research questions:

-

a.

Which psychosocial correlates of energy, fruit, juice, vegetable, fat, sugar snacking, sweetened beverages, fiber, and other dietary consumption have been studied specifically in youth?

-

b.

Which psychosocial factors are clearly and consistently associated with these dietary behaviors in youth?

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

Medical and psychosocial databases (e.g. PubMed, PsychINFO, PsycArticles) as well as references cited in earlier reviews, primary studies and collected articles served to identify potential articles that examined associations between psychosocial factors and dietary intake in pediatric populations. Only papers published in English, between 1990 and May 2009, describing psychosocial factors related to dietary intake were considered for review. No literature searches were conducted after May 27, 2009.

Our search strategy involved using a combination of dietary intake keywords with psychosocial factor keywords to identify relevant articles. For dietary intake, the following keywords were used: eating behavior, dietary behavior, consumption, junk food, high fat food, sodium, fiber, calcium, soda, soft drink, snack food, sugar-laden, beverage, sugar, fast food, sweets, fruit, vegetable, juice, fruit consumption, fruit intake, vegetable consumption, vegetable intake, dietary fat, nutrition, and diet. For psychosocial factors, the following keywords were used: determinants, correlates, self-efficacy, social support, mediation, mediating variables, psychosocial variables, social cognitive theory (SCT), self determination theory (SDT), theory of reasoned action (TRA), theory of planned behavior (TPB), transtheoretical model (TTM), health belief model (HBM), stages of change, SCT, TRA, HBM, SDT, TPB, outcome expectancies, barriers, psychosocial correlates, psychosocial predictors, psychosocial determinants, social theory, psychosocial factors, motivation, knowledge, attitudes, theory, and modeling.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Each study had to meet the following inclusion criteria to be included in this review: people less than 18 years (or mean age within this range) as study sample (special populations were excluded, including pregnant women and athletes); at least one psychosocial variable as an independent variable; a measure of dietary intake (e.g. total energy, fat intake, fruit, vegetable, snack, fast food, calcium, fiber or soft drink consumption) as the dependent variable(s); the papers had to include enough statistical data to be incorporated in the review. Specifically, a correlation coefficient, odds ratio, or beta value as well as a p-value to indicate statistical significance of relationships with a measure of dietary intake were required for inclusion. Because the literature on correlates of eating behaviors in youth is vast, we limited this review paper to cross-sectional and prospective studies. We are currently undertaking a review of determinants of dietary change in intervention studies.

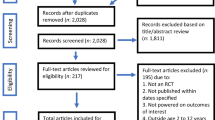

Identification of relevant studies

Potentially relevant papers were selected by screening the titles (first step), abstracts (second step), and the entire article (third step) retrieved through the database searches. Two researchers (A.M. and C.C.) independently conducted this screening. Disagreement about eligibility between the reviewers was resolved through discussion with a third coauthor (S.R).

Data extraction

Two authors (A.M. and C.C.) extracted the data from the identified studies. The research design rating presented for each study was developed by using three previously published rating schemes [33–35]. Based on the quality of the research design, each study was given a rating with one to four asterisks. A.M. and C.C. rated the studies and then cross-checked their results. Disagreement between the reviewers was resolved through discussion with S.R. The criteria used to determine the rating of each study is listed in Table 1. Each study's findings and methodological details, such as sample population details, dietary outcomes, psychosocial determinants assessed, assessment methodology (child and/or parent-report, measurement name, reliability, validity), and statistical analysis methods are listed in Tables 2 and 3.

Summarizing study findings

Modeling after Sallis' review of the psychosocial determinants of physical activity in children and adolescents [36], associations between psychosocial factors and dietary outcomes were coded as '+' for a positive association and '-' for a negative association. Associations were regarded significant when the p-value reported in the study was <0.05. For studies that reported results from univariate and multivariate analysis, we only reported the multivariate results. The results of multivariate analyses provide a more accurate description of a relationship because they control for other potential confounding variables. Using the above-mentioned criteria, 97 distinct psychosocial constructs were found. In order to reduce the number of variables, we combined conceptually similar psychosocial factors (e.g. appeal of food was combined with preference). Outcome categories were created if there were at least 5 articles that addressed the same specific dietary outcome. This decision rule elicited 8 categories, 6 for specific dietary outcomes and 2 'other' categories: Fruit, Juice and Vegetable Consumption, Fat in Diet, Total Energy Intake, Sugar Snacking, Sweetened Beverage Consumption, Dietary Fiber, Other Healthy Dietary Consumption, and Other Less Healthy Dietary Consumption. Findings are reported below using these categories. Consistent findings were defined as having a relationship in the same direction over 60% of the time as seen in at least two independent articles.

Results

Search and selection of studies

The databases search located 4460 titles (Pubmed 3336; PsychInfo 1124) of potentially relevant articles. Other scholarly databases did not yield any new titles. Reference sections of earlier reviews and primary studies added forty-four titles. Screening the titles and abstracts resulted in a selection of 146 articles for full-text review. Sixty-nine of these articles did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in a final inclusion of 77 articles.

From the evaluation of the design and methodology of each paper (Table 2) the main findings are as follows:

-

Forty-eight (62%) of the included papers were studies conducted in the United States (US).

-

Sixty-four (83%) were cross-sectional studies [37–100]. Eleven (14%) were prospective studies [101–111]. Two (3%) were experimental studies [112, 113].

-

Forty-four (57%) studies had a sample smaller than 500 individuals.

-

Forty-three (56%) studies were conducted in children (mean age of less than 13 years); whereas thirty-four (44%) were conducted with adolescents.

-

Thirty-five (45%) studies were conducted in ethnically diverse populations. Six (8%) were among African Americans only; two (3%) among Caucasians only; two (3%) among Hispanics only; and thirty (39%) had insufficient information for assessing representativeness.

-

To assess dietary behaviors, eight studies used variations of a 24-hour dietary recall; twelve used variations of a food record; twenty-seven used a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ); In a majority of the studies (twenty-seven papers) it was unclear whether dietary intake was measured with a FFQ or another type of questionnaire, such as a diet screener; two studies used observation; three studies used weighed food intake. [Note: This does not equal 77 articles and percentages are not presented because there was overlap (two studies (3%) used more than one measure).]

-

Validity and reliability of the dietary intake measure was reported in more than half of the studies. Thirty studies (38%) reported no information on validity. Thirty-seven studies (48%) referenced previous studies. Eleven studies (14%) assessed validity in the article. Twenty-nine studies (38%) reported no information on reliability. Twenty-seven studies (35%) referenced previous studies. Twenty-one studies (27%) assessed reliability in the article.

-

Research design evaluation scores were provided for each study. Forty-nine studies (38%) were rated as strong. Twenty-five studies (32%) were rated as acceptable. Only two studies (3%) were rated as exceptional. One study (1%) rated as weak.

-

Psychosocial determinants of:

-

○ fruit, vegetable, and fruit juice intake were examined in 35 studies;

-

○ fat intake in 16 studies;

-

○ energy intake in 15 studies;

-

○ sugar snacking in 12 studies;

-

○ fiber intake in 10 studies;

-

○ other dietary consumption (e.g. calcium, healthy dietary behavior, milk intake, fast food) in 14 studies.

-

○ 13 studies assessed multiple dietary behaviors (e.g., fruit, vegetable, fruit juice and fat) and since there is overlap, percentages are not presented.

-

Table 3 gives a summary frequency of the use of dietary measures and the percentage of time a dietary measure produced significant findings.

-

35% of studies used a food frequency questionnaire and 36% of studies used other questionnaires (it was unclear whether dietary intake was measured with a food frequency questionnaire or another type of questionnaire such as a food screener).

-

Dietary intake as measured by food frequency questionnaire was significantly related to a psychosocial correlate with 58% frequency; dietary intake as measured by other types of questionnaires was related to a psychosocial correlate with 57% frequency. Dietary intake as measured by food records and food recalls were significantly related to a psychosocial correlate with 61% and 50% frequency, respectively.

Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 summarize the associations between potential determinants of dietary intake among children and adolescents. The determinants were grouped by dietary category: fruit, fruit juice, and/or vegetable consumption, fat intake, total energy intake, sugar snacking, sweetened beverage consumption, fiber intake, other "healthy" dietary consumption, and other less healthy dietary consumption.

Psychosocial Correlates of Fruit, Fruit Juice, and/or Vegetable Consumption

Thirty-five articles tested for psychosocial correlates of fruit, juice, and vegetable consumption defined as consumption of fruit, fruit juice, and/or vegetables (FJV). In several articles, FJV consumption was broken down into more than one outcome variable. Therefore, we report on variables within studies here. Intention to eat healthy was positively associated with FJV consumption in 3 of 5 studies [87, 96, 104] and for 5 out of 7 variables. Knowledge was positively associated with FJV consumption in 6 of 9 articles [40, 42, 70, 84, 96, 97] and for 8 out of 13 variables. Interestingly in one study [84]knowledge was positively associated among girls, but not associated among boys. Liking was positively associated with FJV consumption in 4 of 5 articles [42, 70, 96, 97] and for 6 out of 8 variables. Norms were positively associated with FJV consumption in 3 of 5 articles [48, 63, 92], 6 out of 10 variables. Perceived Modeling was positively associated with FJV consumption in 8 of 9 articles [40, 42, 47, 70, 93, 96, 97, 99] and for 14 out of 16 variables. However, modeling as reported by parent did not show any consistent associations. Preferences were positively associated with FJV consumption in 11 of 13 articles [40, 42, 53, 59, 60, 63, 70, 78, 83, 93, 106] and for 20 out of 26 variables. None of the other psychosocial variables examined, including attitude, availability, perceived barriers, outcome expectations, self-efficacy, social desirability, and social support showed consistent associations with FJV intake. Table 4 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of fruit, juice, and/or vegetable consumption among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Fat Intake

Sixteen articles examined psychosocial correlates of fat intake (combined total daily fat, % energy from fat, saturated fat). Overall, none of the factors examined showed consistent associations with dietary fat intake. Knowledge was not significantly associated with dietary fat in two studies [61, 75] and 4 out of 4 variables. Perceived modeling was not significantly associated with dietary fat in 2 of 3 studies [74, 75] and for 4 out of 5 variables. None of the other factors examined showed consistent associations with dietary fat intake, including social support. However, we were unable to assess the significance of many factors due to the low number of studies that investigated psychosocial variables and their effect on fat intake. Table 5 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of fat intake among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Total Energy Intake

Fifteen articles investigated the psychosocial correlates of total energy intake. Only two variables were consistently significantly positively associated with total energy intake. Knowledge was positively associated with total energy intake in 4 of 6 articles [44, 65, 80, 86] and for 6 out of 9 variables. Social support was positively associated with total energy intake in 2 of 3 articles [86, 98] and for 2 out of 3 variables. None of the other psychosocial variables examined, including intention to eat healthy, perceived modeling, preferences or self-efficacy showed consistent associations with total energy intake. Table 6 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of total energy intake among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Sugar Snacking

Twelve articles examined the psychosocial correlates of sugar intake, which is defined as consumption of snacks and high sugar-sweetened foods, such as candy. Attitude and intentions were the only two variables consistently significantly associated with sugar snacking. In three studies [37, 85, 102], 3 out of 3 variables, attitude towards healthy eating behavior was negatively associated with sugar snacking. Intention to consume sugar was positively associated with sugar snacking in all three of the articles in which it was measured [76, 102, 103] for 3 out of 3 variables. No other factors examined showed consistent associations with sugar snacking due to the small number of articles investigating psychosocial associations with sugar snacking. Table 7 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of sugar snacking among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Sweetened Beverage Consumption

Ten articles examined the psychosocial correlates of sweetened beverage consumption, which is defined as consumption of sodas, sweetened beverages, and/or juice (alone, not in combination with fruits or vegetables). Intention was found to be positively associated with sweetened beverage consumption in two studies [67, 110] and for the two variables measured. Perceived Modeling was shown to be positively associated with sweetened beverage consumption in four studies [47, 64, 97, 110] and for all seven variables measured. However, modeling as reported by parent did not show any consistent associations. Norms were associated with sweetened beverages in all the studies, using all variables. Peer norms and parent norms were positively associated with sweetened beverage consumption in 2 of 3 studies [64, 110]. Milk norms were negatively associated with sweetened beverage consumption in 1 of the 3 studies [91]. None of the other variables examined illustrated consistent associations with sweetened beverage consumption. Table 8 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of sweetened beverage consumption among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Fiber Intake

Five articles evaluated the psychosocial correlates of fiber intake, defined as fiber intake and consumption of high fiber cereal or bread. Both familial and friend social support were positively associated with fiber consumption in 2 studies [38, 89] and for 3 out of 4 variables. No other factors examined showed consistent associations with fiber intake. Table 9 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of fiber intake among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Other "Healthy" Dietary Consumption

Fourteen articles examined the psychosocial correlates of healthy types of dietary consumption, including calcium intake, healthy dietary behavior, green vegetable intake, milk intake, yogurt intake, skim milk (<.1% fat), low fat milk (.5% fat), cereal intake (cornflakes, muesli, etc.), bread intake, and consumption of low fat vending snacks. Norms were positively associated with healthy dietary consumption in 2 of 3 articles [55, 91], 5 out of 8 variables. Perceived modeling was positively associated with healthy dietary consumption in two articles [72, 97], and for 11 out of 16 variables. Modeling as reported by parent did not show any consistent associations. Social support was positively associated with healthy types of dietary consumption in 3 out of 3 articles [66, 71, 72] and for 5 out of 8 variables. This association held true among boys, but not girls [71]. Self-efficacy was significantly positively associated with healthy dietary consumption in 4 out of 5 articles [57, 66, 71, 91], 6 out of 9 variables. None of the other variables examined, including attitude or knowledge, illustrated consistent associations with other healthy dietary consumption. Table 10 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of healthy dietary consumption among children and adolescents.

Psychosocial Correlates of Other Less Healthy Dietary Consumption

Thirteen articles examined the psychosocial correlates of less healthy types of dietary consumption, including fast food, sodium, medium fat milk (1.5% fat), full fat milk (3% fat), margarine/spread intake, inadequate fruit consumption, inadequate vegetable consumption, and inadequate dairy consumption. Intentions to eat a particular less healthy food were positively associated with less healthy dietary consumption in 3 out of 4 studies [76, 107, 110] and for 4 out of 5 variables. Perceived Modeling was positively associated with less healthy dietary consumption for 2 of 2 articles [97, 110] and for 7 out of the 8 variables measured. Modeling as reported by parent did not show any consistent associations. None of the other variables examined, including attitude towards health or norms, were consistently associated with less healthy dietary consumption. Table 11 summarizes the psychosocial correlates of unhealthy dietary consumption among children and adolescents.

Table 12 gives a summary review of the most frequently studied psychosocial correlates by dietary outcome.

Discussion

This review of the literature on psychosocial correlates of dietary intake in children and adolescents illustrates that perceived modeling and dietary intentions to make healthy or less healthy dietary changes (such as intentions to decrease consumption of sugary beverages or intentions to increase consumption of medium fat milk) have the most consistent and positive associations with eating behavior. Other psychosocial correlates such as liking, norms, and preferences were also consistently and positively associated with eating behavior in children and adolescents. However, somewhat surprisingly, availability, knowledge, outcome expectations, self-efficacy and social support did not show consistent relationships across dietary outcomes.

The recurring relationship between the psychosocial correlates of perceived modeling [19, 23, 24, 114], norms [115], and preferences [19, 22, 114] in predicting eating behavior in children and adolescents is supported in other reviews [19, 22–24, 114, 115]. For example, in a review that focused on the environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behavior in youth, van der Horst et al. found the most consistent associations between parental intake and children's fat and F&V intake [23]. That review also found the most consistent association between parent and sibling intake with adolescents' energy and fat intake [23]. A review on determinants of fruit and vegetable intake by Rasmussen et al. also illustrated a positive association between parental intake and fruit and vegetable intake [19]. The current review supports modeling as one of the most powerful psychosocial predictors of dietary intake in youth. However, our review is unique because it illustrates that perceived modeling is the single most consistent correlate of eating behavior. Modeling as reported by a parent is not consistently correlated with dietary intake. Second, this review is unique in its finding that intentions was also a consistent correlate of eating behavior across various samples of children and adolescents and various dietary outcomes.

Our results are quite dissimilar to a recent review of predictors of dietary behavior (fruit and vegetable intake in particular) among adults [20], and this emphasizes the need to examine psychosocial correlates of youth separately from those of adults. The recent review among adults showed that knowledge, self-efficacy, and social support were consistent predictors of fruit and vegetable intake, while we found that these variables did not predict eating behavior in children and adolescents. This finding highlights the fact that findings from adult research do not necessarily apply to pediatric populations; thus it is imperative that research and interventions in youth be tailored specifically to that population.

Self-report food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) and other types of self-report questionnaires or screeners were the most frequently used methods to measure dietary intake in youth. Only 10% of studies used dietary recalls and 16% used dietary records, which are considered to be more valid means of assessing dietary intake [116, 117]. FFQs delivered a higher percentage of significant correlations with psychosocial variables while stronger measures of dietary intake (i.e. dietary recalls or dietary records) resulted in lower frequency of correlation with psychosocial variables. Different methods of measuring dietary intake delivered different results. More research is needed in the implementation of different outcome measures.

Intentions, a cognitive variable, was the second most consistent variable in predicting eating behavior, which runs contrary to literature suggesting that children's behavior is driven by more affective, rather than cognitive determinants. However, the finding that knowledge and self-efficacy were not predictive of eating behavior in children suggests that children may not be as cognitive as their adult counterparts. This review was limited by the fact that there are few studies that incorporate theories of health behavior that focus on affective behavioral pathways. Therefore, assessment of affective predictors of health behaviors in pediatric populations remains limited. Further, most theory-based studies are based on cognitive theories of behavior. However, neurobiological evidence demonstrates age-related changes in cerebral functioning from lower-order, emotionally-based, sensory processing towards higher-order, more cognitive and rational, processing of stimuli by means of the prefrontal cortical systems that involve reward anticipation, self-monitoring, and behavioral inhibition [32]. Thus, the ability to make beneficial nutritional choices and regulate behavior may be affected by the neurobiological development of cognitive abilities that permit the inhibition of responses, delay of gratification and voluntary change of behavior to bypass short-term rewards in favor of longer-term goals [32]. This research supports the hypothesis that the cognitively-based health behavior models developed for adults may not be appropriate for adolescents who tend to be less rational, and more driven by affect. These findings illustrate that it is important to study children separately from adults and to focus on more affect driven psychological models.

Limitations

Despite the strict protocol for assessing each article, there were some limitations to this study. Most of the studies (83%) included in this review were cross-sectional. Consequently, although such designs are useful in identifying possible theory-based associations, drawing conclusions about directionality and possible causality of associations is not possible. Cross-sectional designs can result in systematic error and an overestimation of associations between the psychosocial variables and eating behaviors [118].

The studies included in this review were diverse in the measurement of the psychosocial variables as well as dietary intake, samples, and analyses used. Therefore, it was not possible to conduct a true meta-analysis. Additionally, in order to summarize the findings of the studies, the authors combined conceptually similar psychosocial determinants into one category, which may have introduced bias.

There are also limitations to many of the studies reviewed here. If only the studies ranked as strong or exceptional were included in the review, twenty-six of the 77 articles would be excluded, resulting in a final inclusion of 51 articles. If only these 51 studies are included, norms are no longer associated with eating behavior. Additionally, there are no longer any articles to judge the association between outcome expectations and eating behavior. Besides these changes, the overall results of the review would remain the same. However, the review would be less reflective of the entire literature.

Additionally, most studies relied on self-report of dietary intake, which has been shown to be considerably unreliable, having high rates of mis-reporting, usually in the direction of under-reporting among youth [119]. Furthermore, bias might have been introduced due to possible lack of validity or reliability of both dietary and psychosocial measures. Unfortunately, reliability and validity of dietary and psychosocial measures were not reported in the some of the studies and only a few studies used objective observation to measure the dietary outcome. This illustrates the need for ongoing validity and reliability evaluation to ensure valid and reliable psychosocial and dietary outcome measures for use in cross-sectional as well as longitudinal studies.

Furthermore, certain studies reported only significant findings and did not address non-significant findings; thus there is a potential bias towards significant findings. Our search strategy also only included studies that were published in English in peer-reviewed journals and referenced in electronic databases; therefore, this review may have overlooked important studies published in other languages.

Lastly, this review did not separate children and adolescents into distinct categories, although research has suggested that children and adolescents exhibit different health behaviors [11]. However, separation by age-group yielded too few studies per variable per group to enable interpretation of findings.

Implications and Future Directions

The goal of this literature review was to assess and report the most promising psychosocial correlates of eating behavior in children and adolescents in order to inform development of interventions. A major strength of this review is that it included a diverse and large sample of studies. For example, studies included samples from many different countries, thus enhancing the generalizability of findings to children and adolescents around the world. Because previous reviews have looked at a single eating behavior (e.g. FVJ consumption only) among adult populations [20], this study addresses a key gap in the literature to serve as a tool for behavioral theorists and interventionists by investigating the psychosocial correlates of diverse eating behaviors in children and adolescents. Strong evidence was found for intentions, perceived modeling, norms, liking, and preferences as consistent correlates of the eating behavior of children and adolescents across dietary outcomes. Comparison of the outcomes of this review paper with recent reviews of the adult literature suggests that determinants of eating behavior differ between adult and pediatric populations. For instance, among adults, knowledge and outcome expectations are consistent correlates of eating behaviors, while in children, they are not. This supports our earlier work showing that knowledge does not impact behavior consistently in youth [11]. A key finding from this review is that health behavior theory as well as research on affective pathways relevant to youth populations is lacking.

Future intervention research may benefit from the incorporation of findings from this review to create more effective adolescent and childhood dietary interventions by targeting the variables shown in this review that are most consistently associated with the various eating behaviors such as intentions, modeling, norms, liking, and preferences. Based on the fact that these constructs have repeatedly been found to be related to dietary behavior, intervening on these factors may be the best way to elicit dietary change. Future research should also investigate the variables that have been insufficiently examined to date, particularly the variables rooted in affective theories. It is quite plausible that affective factors, such as motivation [120], executive control [121], or meanings of behavior [122] might drive the dietary behavior of children and adolescents.

Lastly, future research should investigate the psychosocial correlates of several dietary behaviors that are known to influence weight and metabolic health such as fat and fiber [123] that have been understudied.

Conclusion

This review examined the correlates of various dietary intake; Fruit, Juice and Vegetable Consumption, Fat in Diet, Total Energy Intake, Sugar Snacking, Sweetened Beverage Consumption, Dietary Fiber, Other Healthy Dietary Consumption, and Other Less Healthy Dietary Consumption in cross-sectional and prospective studies for children and adolescents. The correlates most consistently supported by evidence were perceived modeling, dietary intentions, norms, liking and preferences. More prospective studies on the psychosocial determinants of eating behavior and broader theoretical perspectives should be examined in future research.

References

Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S: Diet and risk of type ii diabetes: The role of types of fat and carbohydrate. Diabetologia. 2001, 44: 805-817. 10.1007/s001250100547.

Mann JI: Diet and risk of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2002, 360: 783-9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09901-4.

Garcia-Palmieri MR, Sorlie P, Tillotson J, Costas R, Cordero E, Rodriguez M: Relationship of dietary intake to subsequent coronary heart disease incidence: The puerto rico heart health program. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980, 33: 1818-27.

Hooper L: Dietary fat intake and prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review. BMJ. 2001, 322: 757-763. 10.1136/bmj.322.7289.757.

Mensink RP, Aro A, Den Hond E, German JB, Griffin BA, ten Meer HU, Mutanen M, Pannemans D, Stahl W: Passclaim-diet-related cardiovascular disease. Eur J Nutr. 2003, 42: I6-27. 10.1007/s00394-003-1102-2.

Ness AR: Fruit and vegetables, and cardiovascular disease: A review. Int J Epidemiol. 1997, 26: 1-13. 10.1093/ije/26.1.1.

Howe GR, Benito E, Castelleto R, Cornee J, Esteve J, Gallagher RP, Iscovich JM, Deng-ao J, Kaaks R, Kune GA: Dietary intake of fiber and decreased risk of cancers of the colon and rectum: Evidence from the combined analysis of 13 case-control studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992, 84: 1887-96. 10.1093/jnci/84.24.1887.

Cummings JH, Bingham SA: Diet and the prevention of cancer. BMJ. 1998, 317: 1636-40.

DiPietro L, Mossberg HO, Stunkard AJ: A 40-year history of overweight children in stockholm: Life-time overweight, morbidity, and mortality. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994, 18: 585-90.

Freedman DS, Shear CL, Burke GL, Srinivasan SR, Webber LS, Harsha DW, Berenson GS: Persistence of juvenile-onset obesity over eight years: The bogalusa heart study. Am J Public Health. 1987, 77: 588-92. 10.2105/AJPH.77.5.588.

Spruijt-Metz D: Adolescence, affect and health. Studies in adolescent development. Edited by: Jackson S. 1999, London: Psychology Press

Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Baranowski J: Psychosocial correlates of dietary intake: Advancing dietary intervention. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999, 19: 17-40. 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.17.

Baranowski T, Lin LS, Wetter DW, Resnicow K, Hearn MD: Theory as mediating variables: Why aren't community interventions working as desired?. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997, 7: 10.1016/S1047-2797(97)80011-7.

Brown L, DiClemente R, Reynolds L: Hiv prevention for adolescents: Utility of the health belief model. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1991, 3: 50-59.

Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK: Moving forward: Research and evaluation methods for health behavior and health education. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. The jossey-bass health series. 1990, San Francisco, CA, US:Jossey-Bass, 428-435.

eds: Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 1997, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2

Bentler PM, Speckart G: Models of attitude-behavior relations. Psychological Review. 1979, 86: 452-464. 10.1037/0033-295X.86.5.452.

Green LW, Kreuter MW: Health promotion planning: An educational and environmental approach. 1991, Mountain View, Toronto, London: Mayfield Publishing Company

Rasmussen M, Krolner R, Klepp KI, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E, Due P: Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part i: Quantitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006, 3: 22-10.1186/1479-5868-3-22.

Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeah M-C, Resnicow K: Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2008, 34: 535-543. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028.

Taylor JP, Evers S, McKenna M: Determinants of healthy eating in children and youth. Can J Public Health. 2005, 96 (Suppl 3): S20-6-S22-9.

Shepherd J, Harden A, Rees R, Brunton G, Garcia J, Oliver S, Oakley A: Young people and healthy eating: A systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. Health Educ Res. 2006, 21: 239-57. 10.1093/her/cyh060.

Horst van der K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe F, Brug J: A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res. 2007, 22: 203-26. 10.1093/her/cyl069.

Patrick H, Nicklas TA: A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005, 24: 83-92.

Davis JN, Hodges VA, Gillham MB: Normal-weight adults consume more fiber and fruit than their age-and height-matched overweight/obese counterparts. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006, 106: 833-840. 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.013.

Pereira MA, Jacobs DR, Pins JJ, Raatz SK, Gross MD, Slavin JL, Seaquist ER: Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 75: 848.

Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB: Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: A systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 84: 274.

Westerterp KR, Verboeket-Van De Venne W, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Velthuis-Te Wierik EJM, De Graaf C, Weststrate JA: Dietary fat and body fat: An intervention study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996, 20: 1022-1026.

Kirscht JP: Preventive health behavior: A review of research and issues. Health Psychology. 1983, 2: 277-301. 10.1037/0278-6133.2.3.277.

Spruijt-Metz D, Saelens B: Behavioral aspects of physical activity in childhood and adolescence. Handbook of pediatric obesity: Etiology, pathophysiology and prevention. 2005, Boca Raton, FL:Taylor & Francis Books/CRC Press, 227-250.

Spruijt-Metz D, Spruijt R, Xie B, Chou C-P: Factorial validity, invariance and generalizability of the meanings of exercise scale. Obes Res. 2004, 12: A74-A75.

Killgore WD, Yurgelun-Todd DA: Developmental changes in the functional brain responses of adolescents to images of high and low-calorie foods. Dev Psychobiol. 2005, 47: 377-97. 10.1002/dev.20099.

Ammerman AS, Lindquist CH, Lohr KN, Hersey J: The efficacy of behavioral interventions to modify dietary fat and fruit and vegetable intake: A review of the evidence. Prev Med. 2002, 35: 25-41. 10.1006/pmed.2002.1028.

Wilson MG, Holman PB, Hammock A: A comprehensive review of the effects of worksite health promotion on health-related outcomes. Am J Health Promot. 1996, 10: 429-35.

Seymour JD, Yaroch AL, Serdula M, Blanck HM, Khan LK: Impact of nutrition environmental interventions on point-of-purchase behavior in adults: A review. Prev Med. 2004, 39 (Suppl 2): S108-36. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.002.

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC: A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000, 32: 963-75. 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014.

Astrom AN, Kiwanuka SN: Examining intention to control preschool children's sugar snacking: A study of carers in uganda. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006, 16: 10-8. 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00671.x.

Ayala GX, Baquero B, Arredondo EM, Campbell N, Larios S, Elder JP: Association between family variables and mexican american children's dietary behaviors. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007, 39: 62-69. 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.025.

Befort C, Kaur H, Nollen N, Sullivan DK, Nazir N, Choi WS, Hornberger L, Ahluwalia JS: Fruit, vegetable, and fat intake among non-hispanic black and non-hispanic white adolescents: Associations with home availability and food consumption settings. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006, 106: 367-73. 10.1016/j.jada.2005.12.001.

Bere E, Klepp KI: Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among norwegian schoolchildren: Parental and self-reports. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7: 991-8.

Berg MC, Jonsson I, Conner MT, Lissner L: Relation between breakfast food choices and knowledge of dietary fat and fiber among swedish schoolchildren. J Adolesc Health. 2002, 31: 199-207. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00391-9.

Brug J, Tak NI, te Velde SJ, Bere E, de Bourdeaudhuij I: Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: Results from observational studies. Br J Nutr. 2008, 99 (Suppl 1): S7-S14.

Campbell KJ, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Carver A, Garnett SP, Baur LA: Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity. 2007, 15: 719-730. 10.1038/oby.2007.553.

Corwin S, Sargent R, Rheaume C, Saunders R: Dietary behaviors among fourth graders: A social cognitive theory approach. American Journal of Health Behavior. 1999, 23: 182-197.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Klesges LM, Watson K, Sherwood NE, Story M, Zakeri I, Leachman-Slawson D, Pratt C: Anthropometric, parental, and psychosocial correlates of dietary intake of african-american girls. Obes Res. 2004, 12 (Supl): 20S-31S. 10.1038/oby.2004.265.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Owens E, Marsh T, Rittenberry L, de Moor C: Availability, accessibility, and preferences for fruit, 100% fruit juice, and vegetables influence children's dietary behavior. Health Educ Behav. 2003, 30: 615-26. 10.1177/1090198103257254.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Rittenberry L, Cosart C, Hebert D, de Moor C: Child-reported family and peer influences on fruit, juice and vegetable consumption: Reliability and validity of measures. Health Educ Res. 2001, 16: 187-200. 10.1093/her/16.2.187.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Rittenberry L, Olvera N: Social-environmental influences on children's diets: Results from focus groups with african-, euro- and mexican-american children and their parents. Health Educ Res. 2000, 15: 581-90. 10.1093/her/15.5.581.

Cusatis DC, Shannon BM: Influences on adolescent eating behavior. J Adolesc Health. 1996, 18: 27-34. 10.1016/1054-139X(95)00125-C.

Dausch JG, Story M, Dresser C, Gilbert GG, Portnoy B, Kahle LL: Correlates of high-fat/low-nutrient-dense snack consumption among adolescents: Results from two national health surveys. Am J Health Promot. 1995, 10: 85-8. 10.1093/heapro/10.2.85.

Di Noia J, Schinke SP, Prochaska JO, Contento IR: Application of the transtheoretical model to fruit and vegetable consumption among economically disadvantaged african-american adolescents: Preliminary findings. Am J Health Promot. 2006, 20: 342-8.

Djuric Z, Cadwell WF, Heilbrun LK, Venkatramanamoorthy R, Dereski MO, Lan R, Casey RJ: Relationships of psychosocial factors to dietary intakes of preadolescent girls from diverse backgrounds. Matern Child Nutr. 2006, 2: 79-90. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2006.00051.x.

Domel SB, Thompson WO, Davis HC, Baranowski T, Leonard SB, Baranowski J: Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption among elementary school children. Health Educ Res. 1996, 11: 299-308. 10.1093/her/11.3.299.

Feunekes GIJ, des Graaf C, Meyboom S, van Staveren WA: Food choice and fat intake of adolescents and adults: Associations of intakes within social networks. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory. 1998, 27: 645-656.

Fila S, Smith C: Applying the theory of planned behavior to healthy eating behaviors in urban native american youth. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006, 3: 11-10.1186/1479-5868-3-11.

Fisher JO, Birch LL: Fat preferences and fat consumption of 3- to 5-year-old children are related to parental adiposity. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995, 95: 759-64. 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00212-X.

French SA, Story M, Hannan P, Breitlow KK, Jeffery RW, Baxter JS, Snyder MP: Cognitive and demographic correlates of low-fat vending snack choices among adolescents and adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999, 99: 471-5. 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00117-0.

Frenn M, Malin S, Villarruel AM, Slaikeu K, McCarthy S, Freeman J, Nee E: Determinants of physical activity and low-fat diet among low income african american and hispanic middle school students. Public Health Nurs. 2005, 22: 89-97. 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220202.x.

Gallaway MS, Jago R, Baranowski T, Baranowski JC, Diamond PM: Psychosocial and demographic predictors of fruit, juice and vegetable consumption among 11–14-year-old boy scouts. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10: 1508-14. 10.1017/S1368980007000742.

Gibson EL, Wardle J, Watts CJ: Fruit and vegetable consumption, nutritional knowledge and beliefs in mothers and children. Appetite. 1998, 31: 205-28. 10.1006/appe.1998.0180.

Gonzales EN, Marshall JA, Heimendinger J, Crane LA, Neal WA: Home and eating environments are associated with saturated fat intake in children in rural west virginia. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002, 102: 657-63. 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90151-3.

Gracey D, Stanley N, Burke V, Corti B, et al: Nutritional knowledge, beliefs and behaviours in teenage school students. Health Education Research. 1996, 11: 187-204. 10.1093/her/11.2.187.

Granner ML, Sargent RG, Calderon KS, Hussey JR, Evans AE, Watkins KW: Factors of fruit and vegetable intake by race, gender, and age among young adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004, 36: 173-80. 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60231-5.

Grimm GC, Harnack L, Story M: Factors associated with soft drink consumption in school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004, 104: 1244-9. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.05.206.

Harvey-Berino J, Hood V, Rourke J, Terrance T, Dorwaldt A, Secker-Walker R: Food preferences predict eating behavior of very young mohawk children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997, 97: 750-3. 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00186-7.

Ievers-Landis CE, Burant C, Drotar D, Morgan L, Trapl ES, Kwoh CK: Social support, knowledge, and self-efficacy as correlates of osteoporosis preventive behaviors among preadolescent females. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003, 28: 335-45. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg023.

Kassem NO, Lee JW: Understanding soft drink consumption among male adolescents using the theory of planned behavior. J Behav Med. 2004, 27: 273-296. 10.1023/B:JOBM.0000028499.29501.8f.

Koui E, Jago R: Associations between self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption and home availability of fruit and vegetables among greek primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11: 1142-8. 10.1017/S1368980007001553.

Kremers SPJ, Brug J, de Vries H, Engels RCME: Parenting style and adolescent fruit consumption. Appetite. 2003, 41: 43-50. 10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00038-2.

Kristjansdottir A, Thorsdottir I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Due P, Wind M, Klepp K-I: Determinants of fruit and vegetable intake among 11-year-old schoolchildren in a country of traditionally low fruit and vegetable consumption. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006, 3: 41-10.1186/1479-5868-3-41.

Larson NI, Story M, Wall M, Neumark-Sztainer D: Calcium and dairy intakes of adolescents are associated with their home environment, taste preferences, personal health beliefs, and meal patterns. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006, 106: 1816-24. 10.1016/j.jada.2006.08.018.

Lee S, Reicks M: Environmental and behavioral factors are associated with the calcium intake of low-income adolescent girls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003, 103: 1526-9. 10.1016/j.jada.2003.08.020.

Lin W, Yang HC, Hang CM, Pan WH: Nutrition knowledge, attitude, and behavior of taiwanese elementary school children. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007, 16 (Suppl 2): 534-46.

Martens MK, van Assema P, Brug J: Why do adolescents eat what they eat? Personal and social environmental predictors of fruit, snack and breakfast consumption among 12–14-year-old dutch students. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8: 1258-65. 10.1079/PHN2005828.

Masu R, Sallis JF, Berry CC, Broyles SL, Elder JP, Nader PR: The relationship between health beliefs and behaviors and dietary intake in early adolescence. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002, 102: 421-4. 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90099-4.

Mesters I, Oostveen T: Why do adolescents eat low nutrient snacks between meals? An analysis of behavioral determinants with the fishbein and ajzen model. Nutr Health. 1994, 10: 33-47.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum RW: Correlates of inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Prev Med. 1996, 25: 497-505. 10.1006/pmed.1996.0082.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M: Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents. Findings from project eat. Prev Med. 2003, 37: 198-208. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00114-2.

Perez-Lizaur AB, Kaufer-Horwitz M, Plazas M: Environmental and personal correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in low income, urban mexican children. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008, 21: 63-71.

Pirouznia M: The association between nutrition knowledge and eating behavior in male and female adolescents in the us. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2001, 52: 127-32. 10.1080/713671772.

Rafiroiu AC, Anderson EP, Sargent RG, Evans A: Dietary practices of south carolina adolescents and their parents. Am J Health Behav. 2002, 26: 200-12.

Reinaerts E, de Nooijer J, Candel M, de Vries N: Explaining school children's fruit and vegetable consumption: The contributions of availability, accessibility, exposure, parental consumption and habit in addition to psychosocial factor. Appetite. 2007, 48: 248-258. 10.1016/j.appet.2006.09.007.

Resnicow K, Davis-Hearn M, Smith M, Baranowski T, Lin LS, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Wang DT: Social-cognitive predictors of fruit and vegetable intake in children. Health Psychol. 1997, 16: 272-6. 10.1037/0278-6133.16.3.272.

Reynolds K, Hinton A, Shewchuck R, Hickey C: Social cognitive model of fruit and vegetable consumption in elementary school children. J Nutr Educ Behav. 1999, 31: 23-30. 10.1016/S0022-3182(99)70381-X.

Rise J, Holund U: Prediction of sugar behaviour. Community Dent Health. 1990, 7: 267-72.

Risvas G, Panagiotakos DB, Chrysanthopoulou S, Karasouli K, Matalas AL, Zampelas A: Factors associated with food choices among greek primary school students: A cluster analysis in the elpydes study. J Public Health (Oxf). 2008, 30: 266-73. 10.1093/pubmed/fdn039.

Sandvik C, Gjestad R, Brug J, Rasmussen M, Wind M, Wolf A, Pérez-Rodrigo C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Samdal O, Klepp K-I: The application of a social cognition model in explaining fruit intake in austrian, norwegian and spanish schoolchildren using structural equation modelling. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007, 4: 57-10.1186/1479-5868-4-57.

Sharma M, Wagner DI, Wilkerson J: Predicting childhood obesity prevention behaviors using social cognitive theory. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2005, 24: 191-203. 10.2190/CPVX-075A-L30Q-2PVM.

Stanton CA, Green SL, Fries EA: Diet-specific social support among rural adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007, 39: 214-218. 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.10.001.

Sun WY, Wu JS: Comparison of dietary self-efficacy and behavior among american-born and foreign-born chinese adolescents residing in new york city and chinese adolescents in guangzhou, china. J Am Coll Nutr. 1997, 16: 127-33.

Thompson VJ, Bachman C, Watson K, Baranowski T, Cullen KW: Measures of self-efficacy and norms for low-fat milk consumption are reliable and related to beverage consumption among 5th graders at school lunch. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11: 421-6.

Thompson VJ, Bachman CM, Baranowski T, Cullen KW: Self-efficacy and norm measures for lunch fruit and vegetable consumption are reliable and valid among fifth grade students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007, 39: 2-7. 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.06.006.

Vereecken CA, Van Damme W, Maes L: Measuring attitudes, self-efficacy, and social and environmental influences on fruit and vegetable consumption of 11- and 12-year-old children: Reliability and validity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105: 257-61. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.008.

Videon TM, Manning CK: Influences on adolescent eating patterns: The importance of family meals. J Adolesc Health. 2003, 32: 365-73. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00711-5.

Wardle J, Carnell S, Cooke L: Parental control over feeding and children's fruit and vegetable intake: How are they related?. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105: 227-32. 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.006.

Wind M, de Bourdeaudhuij I, te Velde SJ, Sandvik C, Due P, Klepp KI, Brug J: Correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption among 11-year-old belgian-flemish and dutch schoolchildren. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2006, 38: 211-21. 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.02.011.

Woodward DR, Boon JA, Cumming FJ, Ball PJ, et al: Adolescents' reported usage of selected foods in relation to their perceptions and social norms for those foods. Appetite. 1996, 27: 109-117. 10.1006/appe.1996.0039.

Wu T, Stoots JM, Florence JE, Floyd MR, Snider JB, Ward RD: Eating habits among adolescents in rural southern appalachia. J Adolesc Health. 2007, 40: 577-80. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.12.018.

Young EM, Fors SW, Hayes DM: Associations between perceived parent behaviors and middle school student fruit and vegetable consumption. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2004, 36: 2-8. 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60122-X.

Zabinski MF, Daly T, Norman GJ, Rupp JW, Calfas KJ, Sallis JF, Patrick K: Psychosocial correlates of fruit, vegetable, and dietary fat intake among adolescent boys and girls. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006, 106: 814-21. 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.014.

Arcan C, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P, Berg van den P, Story M, Larson N: Parental eating behaviours, home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy foods: Longitudinal findings from project eat. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10: 1257-65. 10.1017/S1368980007687151.

Astrom AN: Validity of cognitive predictors of adolescent sugar snack consumption. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004, 28: 112-121.

Astrom AN, Okullo I: Temporal stability of the theory of planned behavior: A prospective analysis of sugar consumption among ugandan adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004, 32: 426-34. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00186.x.

Backman DR, Haddad EH, Lee JW, Johnston PK, Hodgkin GE: Psychosocial predictors of healthful dietary behavior in adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002, 34: 184-92. 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60092-4.

Baker CW, Little TD, Brownell KD: Predicting adolescent eating and activity behaviors: The role of social norms and personal agency. Health Psychol. 2003, 22: 189-98. 10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.189.

Baxter SD, Thompson WO: Fourth-grade children's consumption of fruit and vegetable items available as part of school lunches is closely related to preferences. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002, 34: 166-171. 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60086-9.

Berg C, Jonsson I, Conner M: Understanding choice of milk and bread for breakfast among swedish children aged 11–15 years: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2000, 34: 5-19. 10.1006/appe.1999.0269.

Gummeson L, Johnsoon I, Conner M: Predicting intentions and behaviour of swedish 10–16 year-olds at breakfast. Food Qual Pref. 1997, 297-306. 10.1016/S0950-3293(97)00013-X.

Lien N, Jacobs DR, Klepp KI: Exploring predictors of eating behaviour among adolescents by gender and socio-economic status. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5: 671-81. 10.1079/PHN2002334.

Horst van der K, Timperio A, Crawford D, Roberts R, Brug J, Oenema A: The school food environment associations with adolescent soft drink and snack consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2008, 35: 217-23. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.022.

Zive MM, Frank-Spohrer GC, Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Elder JP, Berry CC, Broyles SL, Nader PR: Determinants of dietary intake in a sample of white and mexican-american children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998, 98: 1282-9. 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00288-0.

Salvy SJ, Vartanian LR, Coelho JS, Jarrin D, Pliner PP: The role of familiarity on modeling of eating and food consumption in children. Appetite. 2008, 50: 514-8.

Salvy S-J, Romero N, Paluch R, Epstein LH: Peer influence on pre-adolescent girls' snack intake: Effects of weight status. Appetite. 2007, 49: 177-182. 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.011.

Blanchette L, Brug J: Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among 6–12-year-old children and effective interventions to increase consumption. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2005, 18: 431-43. 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2005.00648.x.

Adams LB: An overview of adolescent eating behavior barriers to implementing dietary guidelines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997, 817: 36-48. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48194.x.

Barreti-Connor E: Nutrition epidemiology: How do we know what they ate? 3. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991, 54: 182S-187S.

Gibson RS: Principles of nutritional assessment. 1990, New York, NY: Oxford University Press

Weinstein ND: Misleading tests of health behavior theories. Ann Behav Med. 2007, 33: 1-10. 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_1.

Livingstone MB, Robson PJ: Measurement of dietary intake in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000, 59: 279-93.

Deci EL, Ryan RM: Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. 1985, Springer

Allan JL, Johnston M, Campbell N: Why do people fail to turn good intentions into action? The role of executive control processes in the translation of healthy eating intentions into action in young scottish adults. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 123-10.1186/1471-2458-8-123.

Spruijt-Metz D: Personal incentives as determinants of adolescent health behavior: The meaning of behavior. Health Education Research. 1995, 10: 355-364. 10.1093/her/10.3.355.

Ventura E, Davis J, Byrd-Williams C, Alexander K, McClain A, Lane CJ, Spruijt-Metz D, Weigensberg M, Goran M: Reduction in risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in response to a low-sugar, high-fiber dietary intervention in overweight latino adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009, 163: 320-7. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.11.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NCI-funded USC Center for Transdisciplinary Research on Energetics and Cancer (U54 CA 116848)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

ADM carried out the literature review, data extraction, conceptualization, interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript. CC participated in the literature review, data extraction, and interpretation of the data. STN participated in the data extraction, interpretation of the data and helped to draft the manuscript. ALY contributed to the conceptualization, data interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. DSM participated in the conceptualization, data extraction, interpretation of the data and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

McClain, A.D., Chappuis, C., Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T. et al. Psychosocial correlates of eating behavior in children and adolescents: a review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 6, 54 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-54

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-54