Abstract

Background

Research on the influence of the physical environment on physical activity is rapidly expanding and different measures of environmental perceptions have been developed, mostly in the US and Australia. The purpose of this paper is to (i) provide a literature review of measures of environmental perceptions recently used in European studies and (ii) develop a questionnaire for population monitoring purposes in the European countries.

Methods

This study was done within the framework of the EU-funded project 'Instruments for Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and Fitness (ALPHA)', which aims to propose standardised instruments for physical activity and fitness monitoring across Europe. Quantitative studies published from 1990 up to November 2007 were systematically searched in Pubmed, Web of Science, TRIS and Geobase. In addition a survey was conducted among members of the European network for the promotion of Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA Europe) and European members of the International Physical Activity and Environment Network (IPEN) to identify published or ongoing studies. Studies were included if they were conducted among European general adult population (18+y) and used a questionnaire to assess perceptions of the physical environment. A consensus meeting with an international expert group was organised to discuss the development of a European environmental questionnaire.

Results

The literature search resulted in 23 European studies, 15 published and 8 unpublished. In these studies, 13 different environmental questionnaires were used. Most of these studies used adapted versions of questionnaires that were developed outside Europe and that focused only on the walkability construct: The Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS), the abbreviated version of the NEWS (ANEWS) and the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study (NQLS) questionnaire have been most commonly used. Based on the results of the literature review and the output of the meeting with international experts, a European environmental questionnaire with 49 items was developed.

Conclusion

There is need for a greater degree of standardization in instruments/methods used to assess environmental correlates of physical activity, taking into account the European-specific situation. A first step in this process is taken by the development of a European environmental questionnaire.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite the numerous health benefits associated with an active lifestyle, the majority of adults in Western countries does not participate in regular physical activities of at least moderate intensity. A survey across member states of the European Union found that about two thirds of adults in these countries does not perform sufficient physical activity for health benefits [1]. For effective interventions, an evidence-based knowledge of physical activity determinants including the environmental ones is essential.

There is increasing interest in comprehensive theoretical frameworks (e.g. ecological models) in which, next to individual, social and cultural factors also physical environmental factors are included [2]. From a public health perspective, research about the influence of the physical or built environment, which is defined as "all of the physical parts of were we live and work (e.g., homes, buildings, streets, open spaces, and infrastructure)" [3], on physical activity appears promising. Indeed, environment-changing interventions have the potential to reach a large proportion of the population as well as to achieve sustainable effects.

Research on the contribution of environmental variables in explaining physical activity behaviour is rapidly expanding. The Active Living Research Network Reference list illustrates this growth, with 101 references in 2004, 160 in 2005 and 301 references in 2006, published in 122 different journals [4]. However, the theoretical gains from such a body of literature have remained modest to date. Bauman re-iterates of this lack of progress, "the plethora of cross sectional analytical papers that show small cross sectional associations ... without really striking gold in terms of identifying the solve-all correlates" [5]. This suggests that measuring environmental determinants is a complex process, both in terms of which environmental variables are relevant to measure as well as how to measure these variables accurately.

Studies of the environment and physical activity have typically used two types of exposure measures, (i) measures of perceptions of the environment using a questionnaire, and (ii) objective measures of the environment derived from observations of the environment (audits, ground truthing) or Geographic Information Systems (GIS) data [6].

Early drafts of measures of perceptions of the environment were criticised for their lack of metric data (e.g. repeatability, face validity) [7]. The development of perceived environmental measures has emerged outside of Europe, either from Australia – in particular the SEID (Social Environmental Individual Determinants) study conducted by Giles-Corti and colleagues [8], or from three research centres in the US (North Carolina – [9]; South Carolina – [10]; California – [11]. As the built environment in Europe differs considerably from those in the US or Australia (e.g. compare the environments of European city centres and those of North American suburbs) this raises questions about the applicability of these questionnaires in a European context. As a consequence a small number of European studies have developed their own questionnaires as part of studies or have adapted international questionnaires to the European context. However, today no consensus exists about which environmental questionnaire should be used in Europe. The latter issue is one of the objectives of an EU-funded project called ALPHA (Instruments for Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and Fitness), that will propose standardised instruments for physical activity and fitness monitoring across Europe [12]. Thus the first objective of this study is to conduct a literature review on currently used questionnaires to assess environmental aspects of physical activity in the general population in Europe. This paper presents the results of this review and based on it proposes a environmental questionnaire for population monitoring purposes in European countries.

Methods

PHASE I: Literature review

Data sources

An extensive and systematic literature search was conducted to identify currently used questionnaires to assess environmental aspects of physical activity in Europe using the online databases PubMed, Web of Sciences, Transportation Research Information System (TRIS) and Geobase. The search strategy was based on those of Wendel-Vos and colleagues [13], including physical activity-related keywords as physical (in)activity, walking, bicycling, sports, active transportation and environmental-related keywords as physical environment, environmental influence, built environment and environment perception. The search strategy was initially developed in Pubmed and tailored for use in other databases. The search was also restricted to human studies published in English between 1 January 1990 and 30 November 2007. Furthermore, reference lists of relevant publications that were found were examined.

In addition to the systematic literature search we also conducted a survey among the members of the European network for the promotion of Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA Europe) and European members of the International Physical Activity & the Environment Network (IPEN). We contacted all key expert authors within Europe and asked for details of published or ongoing studies using perceived measures of the physical environment in relation to physical activity.

Data Extraction

Studies were included if they met following inclusion criteria (i) reporting measuring the association between a physical activity behaviour and an aspect of the environment using a specific perceived environmental measure. (ii) reporting the metrics of a perceived environmental measure (iii) being from European origin (iv) conducted in the general adult population, 18 years and older without any specific diseases.

Studies were excluded if they were narrative or focused only on the social, political or economical environment or measured the objective environment instead of perceptions. Primary papers found by the literature search were first independently scanned on title and abstract to check whether they met the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (HS, CF). After the initial screening of the studies on title and abstract, full text of the selected papers were retrieved and scanned again. Finally the (un)published papers, abstracts or theses retrieved from the HEPA-Europe and the IPEN networks were also screened. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third party (IB).

PHASE II. Designing a European environmental perceptions questionnaire

Similar to the development of both long and short forms of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [14], we aimed at designing a long form of the environmental questionnaire for research purposes and a short form for monitoring purposes.

We did not aim to develop an entirely new questionnaire including a list of new items, but selected themes and items that were already used in other questionnaires. The development process consisted of two steps: (1) selecting the themes and (2) selecting the items. To select the themes we used the results of the literature review to identify the key questionnaires that were used most frequently in Europe. Then, common themes between environmental items in these instruments were analysed and grouped together by themes (such as housing type, access to services, and provision for walking and cycling), each of which was considered for inclusion in the final version of the questionnaire.

To select the items a factor analysis was carried out on data on perceptions of the environment collected in one published European study [15] to identify the highest loading items. Items with factor loading above 0.70 were considered for inclusion in the European questionnaire.

Next, a consensus meeting with an international expert group [see Additional file 1] was organised and all items of both forms of the questionnaire were discussed until consensus was reached on which should be included in the final version

Results

Literature search

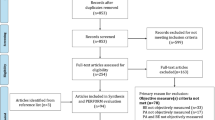

The initial computerised literature search resulted in 1853 studies (see Figure 1). Based on the title or the abstract, 1368 papers did not fulfil the inclusion criteria and were excluded together with 184 duplicates. The remaining 301 papers were retrieved and scanned against the inclusion criteria. At this step, 288 papers were excluded (most of them (253) were non-European papers) resulting in 14 papers [15–28]. The reference search did not result in further papers fulfilling the inclusion criteria.

Contacting the members of the HEPA Europe and the IPEN networks yielded twenty papers, abstracts or theses of recent or ongoing studies and resulted in nine additional studies that were not detected by the online literature search, eight unpublished and one published study([29–32, 21]; Chaix (personal communication); Davey (personal communication); Trayers (personal communication); Van Keulen (personal communication)).

Thus, this systematic review on currently used environmental questionnaires in Europe identified 23 studies that fully met the inclusion criteria.

General characteristics of the studies

All 23 studies are summarized in Table 1. Of the 23 detected studies, 15 had been published at the time of the data collection exercise and eight had not. Eight of the 15 published papers were published in the last two years. Nine of the 23 studies were carried out in the United Kingdom, two each in Belgium and Austria, one each in Germany, Sweden, Turkey, Portugal, France, Denmark and the Netherlands, and three studies in two or more EU countries. Study population size varied from 98 to 16230 participants. In 16 of the studies both female as male adults were included, in two studies the participants were university students, in two studies participants were elderly women and men and one study included only female participants. In total 13 different questionnaires were used; the number of the environmental items in these questionnaires varied from two to 108.

Measures of environmental perceptions

Table 2 presents details for the measures of environmental perceptions used most frequently within a European context. The table also includes details of published data on the metrics of each measure and the definitions and criteria used for scale within each measure.

The Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS) and the abbreviated version of the NEWS (ANEWS) and the Neighbourhood Quality of Life Study (NQLS) have been most commonly used (eight times). NEWS has been used in a number European studies in conjunction with IPAQ. Most studies reported some adaptation of the NEWS items in terms of language and readability. Sometimes NEWS items that were considered unsuitable for the European context were removed and sometimes other items were added. The NEWS was assessed for its metrics in the US, Australia and Belgium and it appeared to have adequate metric properties [11, 33–35, 15] and had adequate correlations with objective assessments of environments [11, 34].

The IPAQ Environmental module (IPAQE) has been used less extensively (two studies) but is closely aligned with the popular IPAQ measure of physical activity. IPAQE was developed by the members of the IPAQ core group [21] and reflects current opinions and experiences on environmental correlates. The measure was developed in conjunction with IPAQ as a tool for population monitoring. The questionnaire can be administered via the mail or telephone.

The Cycling for Transport (C4T) measure was used in an Austrian study of environmental, social and personal correlates of cycling for transportation for university students [28]. The measure was developed using a review of environmental correlates of cycling and subsequent focus group discussions among student cyclists. This measure is the only specific measure for cycling.

The Perceptions of Local Environment (PLE) measure was used as part of Dr David Ogilvie's PhD thesis, looking at perceptions of the environment in relation to active travel. The measure has been assessed for test-retest reliability and is clearly applicable in the UK [31].

The Active for Life (A4L) measure was used as part of a study looking at perceptions of the environment in relation to walking with a sample of adults across England [19, 36]. The measure is specific to walking but has not yet been assessed for its metrics.

The questionnaire Residential Environment and Coronary Disease (RECORD) was developed recently by Basile Chaix in France and assessed aspects of physical activity and of the related residential environment. The questionnaire also includes specific aspects of the social environment but has not yet been assessed for its metrics.

Criteria for perceived environmental measure for Europe

The ideal European perceived environmental measure should be able: (1) to be applicable to the European context across wide range of different environmental contexts and behaviour patterns; (2) to be comparable across European data sets; (3) to have clearly defined neighbourhood and area properties, cogent with resident's definitions; (4) to be comparable with objective measures of the environment as related to physical activity; (5) to have established metric properties (temporality, face validity, repeatability); (6) to relate specific environmental items to specific physical activities, particularly walking and cycling for leisure and transport; (7) to be easy to administer by mail, telephone or face to face.

Not surprisingly, none of the eight key questionnaires met all of the above criteria. Therefore, we developed an environmental questionnaire specific for the European context.

Designing a European environmental questionnaire

The first step in designing a European environmental measure was to select the themes that should be asked for. This was done by analysing the common themes between environmental items in the eight key questionnaires. The table in the additional file 2 [see additional file 2] presents the full list of items from all eight measures, categorised per theme. The measures have very similar clusters of environmental themes, particularly NEWS, ANEWS, and NQLS (as they are modifications of the same base questionnaire). These common themes are: (1) housing types; (2) local facilities; (3) access to services; (4) street connectivity; (5) places for walking and cycling; (6) neighbourhood surroundings/aesthetics; (7) safety from traffic; (8) safety from crime.

The shorter measures (IPAQE, C4T, A4L, PLE, and RECORD) also include items related to other themes. In addition, NEWS asked questions on perceived satisfaction with the neighbourhood levels of facilities, crime, safety, services, connectivity, and aesthetics. NQLS included items related to physical activity opportunities and exercise equipment at home and within the local environment. It also covered aspects of social cohesion and social capital. RECORD also assessed social cohesion. One item unique to IPAQE and PLE was the number of motor vehicles available in the household. RECORD was the only questionnaire that included an item about quality of sports equipments and one item about vandalism and graffiti.

After identifying the common themes, nine of them were selected for the questionnaire (both long and short form version), taking into account the guidelines mentioned earlier. The selected themes were: (1) types of residences in your neighbourhood,(2) distances to local facilities, (3) walking or cycle infrastructure in your neighbourhood, (4) maintenance of infrastructure in your neighbourhood, (5) neighbourhood safety, (6) how pleasant is your neighbourhood, (7) cycling and walking network, (8) home environment, (9) workplace or study environment.

A second step was to select the items for each theme. As the NEWS questionnaire was one of the most commonly used measures, factor analysis was done on NEWS data obtained from a previous study in Belgium [15]. Based on these results, the items with high factor loadings (>0.70) were selected for the questionnaire, e.g.: ' stores are within easy walking distance of my home' 'There are sidewalks in most of the streets in my neighbourhood' 'The sidewalks in my neighbourhood are well maintained' ' The crime rate in my neighbourhood makes it unsafe to go on walks at night.'.

If applicable, NEWS items were included in their original form, making it possible to compare future datasets with international studies using the NEWS questionnaire. A draft questionnaire was constructed following discussions between all authors of this manuscript, and a consensus meeting with an international expert group was then organised to make a final selection of items. This comprised nine themes with a total of 49 items for the long form [see additional file 3]. For the short form of the questionnaire [see additional file 4] the number of items was reduced to 11 items, but a minimum one item was included within each theme.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic overview of perceived environmental measures in relation to physical activity that are currently used in Europe in order to develop a questionnaire for population monitoring purposes in the EU member states. In total 23 published or unpublished European studies were identified by literature search. This is a small number compared with the increasing number of international environmental studies (mostly from the US and Australia) that have been conducted in recent years. This and the fact that most of the studies have been published very recently or are still underway, indicates that research about the influence of the physical environment on physical activity is still in its infancy in Europe.

There were eight key environmental questionnaires that have been identified in the European literature. The NEWS, ANEWS and the NQLS have been most commonly used. However, the NEWS and its modified versions were all developed and tested on their metric properties outside Europe. Most European authors who used these questionnaires in their studies reported some adaptations of the NEWS items both in terms of language and readability as in removing unsuitable items or adding new ones. Consequently, this raises questions about the appropriateness of the use of the original NEWS in a European context. Other authors also developed their own (shorter) questionnaire introducing new items. So, similar with international literature [37] there is inconsistency in measuring the perceived environment in Europe and is it difficult to make inter-study comparisons. Thus there is a need for a greater degree of standardization in perceived environmental measures.

As none of the identified key questionnaires comply with all the desired elements of an ideal European environmental questionnaire, steps were taken to design a European instrument. Two versions (long and short) of a European environmental questionnaire were designed taking into account the earlier mentioned guidelines:

-

(1)

The European instrument was specifically designed for a European situation, including items of key questionnaires designed in Europe. To increase the comparability with international studies, NEWS items were also included on the condition that they were applicable within the European context. Future research should investigate whether this questionnaire represents an appropriate instrument for assessing perceptions of the environment in all parts of Europe, and indeed whether or not a standardised instrument is possible at all. It is, for example, very difficult to measure perceptions of safety across Europe as the ways in which people perceive safety are influenced by many factors, including social and cultural norms, and previous personal experiences, that vary greatly both between and within countries.

-

(2)

The long IPAQ has been thoroughly tested, and validated against objective assessment of physical activity (accelerometry) [14, 38], and has recently been used (in a modified version) for measuring physical activity in European populations [39, 40]. Most of the other measurements discussed in this paper focus on transport-related physical activity (usually walking) and leisure time physical activity (usually walking, sometimes cycling or sports), and only NQLS assesses the domain of physical activity at home. Except for the study by de Geus et al. [29], none of the reviewed questionnaires attempted to assess environmental items in relation to work. In the study of de Geus et al. some questions were added to the NEWS questionnaire including "destinations to work", "facilities for cyclists at the workplace" and "traffic variables on the road to work". However, the European instrument now includes subscales related to all the four physical activity domains i.e. transport-related physical activity, physical activity at work, physical activity at home and leisure time physical activity.

-

(3)

Another issue that increases the inconsistency in measurements is the lack of standardisation in neighbourhood definitions. These are ranging from vague formulations as 'neighbourhood' and 'local area' to more specific definitions 'within a 5 to 10 minute walk'. In the European questionnaire, the following definition of neighbourhood is used: "By your neighbourhood we mean the area ALL around your home that you could walk to in 10–15 minutes – approx 1.5 km" (or "1 mile" for UK-context).

-

(4)

(5) As Bauman [5] already noted there is a need for improved and more sophisticated exposure measures (perceived and objective), and better assessment of walking and related behaviours. Only one of the reviewed studies compared the assessment of perceptions with objective measurements [15]. In the international literature the number of such studies is also limited [13]. However some studies have shown that for example NEWS has adequate correlations with objective assessments of environments [11, 34]. A positive finding is that the questionnaires that are developed inside Europe have shown good metric properties. More research is needed to confirm if the European questionnaire is comparable with objective measures and if the English and translated versions of the questionnaire have valid metric properties in their relevant countries.

-

(6)

In the European instrument items were included to assess the influence of the physical environment on not only walking but also on cycling behaviour. In contrast with the US and Australia, cycling is a prevalent physical activity in many European countries, both as leisure physical activity [41] and as transport-related behaviour [42] and therefore measuring cycling infrastructure is very relevant in European studies.

-

(7)

Most of the existing measurements have been administered by mail which is the most feasible type of administration in population monitoring. Nevertheless the length of some measurements is too long for monitoring (e.g. NQLS 108 items, NEWS, 98 items), especially knowing that the environmental measurement will be part of a broader (physical activity) assessment. Therefore, efforts were done to design a shorter questionnaire. The long version of the European instrument counts 49 items, which seems feasible for research purposes. Further, a short form of 11 items was developed for monitoring purposes.

Conclusion

Most of the identified European studies used adapted versions of questionnaires that were developed outside Europe and focused only on walkability. There is need for a greater degree of standardization in measurements of the perceived environment, taking into account the European-specific situation, and including the influence of the physical environment on cycling behaviour. On behalf of the ALPHA project a first step of standardization was taken: the authors of this review, together with an international expert group, developed an environmental questionnaire specifically for use within the European context. Two versions were developed: a long version for research purposes [see additional file 3] and a short version for monitoring purposes [see additional file 4]. Future research is needed to test this questionnaire for reliability and validity in different languages and in different European countries.

References

Sjöström M, Oja P, Hägströmer M, Smith BJ, Bauman A: Health-enhancing physical activity across European Union countries: the Eurobarometer study. J Public Health. 2006, 14: 291-300. 10.1007/s10389-006-0031-y.

Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M: Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 1998, 15: 379-397. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00076-2.

Centers for Disease control and Prevention: Impact of the built environment on health. 2008, [http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/publications/factsheets/ImpactoftheBuiltEnvironmentonHealth.pdf]

Kerry J, Rosenberg D, Forman H: Introduction to the Active Living Research Reference List for January–December 2006. 2008, [http://www.activelivingresearch.org/alr/alr/files/whole2006_letter_citations_abstract_online.doc]

Bauman A: The physical environment and physical activity: moving from ecological associations to intervention evidence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59: 535-536. 10.1136/jech.2004.032342.

Foster C, Hillsdon M, Jones A, Grundy C, Wilkinson P, White M, et al: Objective Measures of the Environment and Physical Activity – Results of the Environment and Physical Activity Study in English adults. Journal of physical activity & health. 2009.

Humpel N, Owen N, Leslie E: Environmental factors associated with adults' participation in physical activity: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2002, 22: 188-199. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00426-3.

Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ: The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002, 54: 1793-1812. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00150-2.

Emery J, Crump C, Bors P: Reliability and validity of two instruments designed to assess the walking and bicycling suitability of sidewalks and roads. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003, 18: 38-46.

Kirtland KA, Porter DE, Addy CL, Neet MJ, Williams JE, Sharpe PA, et al: Environmental measures of physical activity supports: perception versus reality. Am J Prev Med. 2003, 24: 323-331. 10.1016/S0749-3797(03)00021-7.

Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Black JB, Chen D: Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: an environment scale evaluation. Am J Public Health. 2003, 93: 1552-1558. 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1552.

Meusel D, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Hägströmer M, Bergman P, Sjöström M: Assessing Levels of Physical Activity in the European Population – the ALPHA project. Selección. 2007, 16: 9-12.

Wendel-Vos W, Droomers M, Kremers S, Brug J, Van Lenthe F: Potential environmental determinants of physical activity in adults: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2007, 8: 425-440. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00370.x.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al: International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35: 1381-1395. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sallis JF, Saelens BE: Environmental correlates of physical activity in a sample of Belgian adults. Am J Health Promot. 2003, 18: 83-92.

Rutten A, Abel T, Kannas L, von LT, Luschen G, Diaz JA, et al: Self reported physical activity, public health, and perceived environment: results from a comparative European study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001, 55: 139-146. 10.1136/jech.55.2.139.

Stahl T, Rutten A, Nutbeam D, Kannas L: The importance of policy orientation and environment on physical activity participation – a comparative analysis between Eastern Germany, Western Germany and Finland. Health Promot Int. 2002, 17: 235-246. 10.1093/heapro/17.3.235.

Titze S, Stronegger W, Owen N: Prospective study of individual, social, and environmental predictors of physical activity: women's leisure running. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2005, 6: 363-376. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2004.06.001.

Foster C, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M: Environmental perceptions and walking in English adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58: 924-928. 10.1136/jech.2003.014068.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Teixeira PJ, Cardon G, Deforche B: Environmental and psychosocial correlates of physical activity in Portuguese and Belgian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8: 886-895. 10.1079/PHN2004673.

Alexander A, Bergman P, Hägströmer M, Sjöström M: IPAQ environmental module; reliability testing. J Public Health. 2006, 14: 76-80. 10.1007/s10389-005-0016-2.

Daskapan A, Tuzun EH, Eker L: Perceived barriers to physical activity in university students. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2006, 5: 615-620.

Poortinga W: Perceptions of the environment, physical activity, and obesity. Social Science & Medicine. 2006, 63: 2835-2846. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.018.

Dawson J, Hillsdon M, Boller I, Foster C: Perceived barriers to walking in the neighborhood environment: a survey of middle-aged and older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2007, 15: 318-335.

Dawson J, Hillsdon M, Boller I, Foster C: Perceived barriers to walking in the neighbourhood environment and change in physical activity levels over 12 months. Br J Sports Med. 2007, 41: 562-568. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033340.

Harrison RA, Gemmell I, Heller RF: The population effect of crime and neighbourhood on physical activity: an analysis of 15 461 adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007, 61: 34-39. 10.1136/jech.2006.048389.

Mota J, Lacerda A, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC, Carvalho J: Perceived neighborhood environments and physical activity in an elderly sample. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2007, 104: 438-444. 10.2466/PMS.104.2.438-444.

Titze S, Stronegger WJ, Janschitz S, Oja P: Environmental, social, and personal correlates of cycling for transportation in a student population. Journal of physical activity & health. 2007, 4: 66-79.

de Geus B, De BI, Jannes C, Meeusen R: Psychosocial and environmental factors associated with cycling for transport among a working population. Health Educ Res. 2008, 23: 697-708. 10.1093/her/cym055.

Mygind O: The significance of the neighbourhood for physical activity. 2007, SDU

Ogilvie D: Shifting towards healthier transport? From systematic review to primary research. PhD Thesis, MRC Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. 2007, Glasgow: University of Glasgow

Wright A, Lowry R, Baker G, Frizsimons C: Do environmental perceptions and self-reported and objective physical activity (PA) levels vary by social deprivation and gender? Baseline results from an intervention trial. ISBNPA meeting, Norway, June 2007. 2008

Brownson RC, Chang JJ, Eyler AA, Ainsworth BE, Kirtland KA, Saelens BE, et al: Measuring the environment for friendliness toward physical activity: a comparison of the reliability of 3 questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 2004, 94: 473-483. 10.2105/AJPH.94.3.473.

Leslie E, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Owen N, Bauman A, Coffee N, et al: Residents' perceptions of walkability attributes in objectively different neighbourhoods: a pilot study. Health & Place. 2005, 11: 227-236. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.05.005.

Cerin E, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD: Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale: validity and development of a short form. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006, 38: 1682-1691. 10.1249/01.mss.0000227639.83607.4d.

Foster C, Hillsdon M, Thorogood M: Environmental perceptions and walking in English adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004, 58: 924-928. 10.1136/jech.2003.014068.

Badland H, Schofield G: Transport, urban design, and physical activity: an evidence-based update. Transportation research Part D – Transport and environment. 2005, 10: 177-196. 10.1016/j.trd.2004.12.001.

Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M: The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9: 755-762. 10.1079/PHN2005898.

European Commission: Health and food. Eurobarometer 64.3. 2006., [http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_246_en.pdf]

Abu-Omar K, Rutten A: Relation of leisure time, occupational, domestic, and commuting physical activity to health indicators in Europe. Prev Med. 2008, 47: 319-323. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.012.

Vaz dA, Graca P, Afonso C, D'Amicis A, Lappalainen R, Damkjaer S: Physical activity levels and body weight in a nationally representative sample in the European Union. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2: 105-113.

Pucher J, Dijkstra L: Promoting safe walking and cycling to improve public health: lessons from The Netherlands and Germany. Am J Public Health. 2003, 93: 1509-1516. 10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1509.

Acknowledgements

This study is being carried out with financial support from the Commission of the European Communities, specific the Public Health Programme 2003–2008 of the Directorate General Health and Consumer Protection Luxembourg, 800259 'Instruments for Assessing Levels of Physical Activity and related Health Determinants' (ALPHA). The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission's views and in no way anticipated the Commission's future policy in this area.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MS, PO, IDB, HR and JMO identified the research question and design of this study as part of the ALPHA project. HS led the literature review and designed the search strategy. HS and CF carried out the literature searches and screened the initial results, extracted data, analysed the findings, drafted the tables and the manuscript. HS, CF, HR, PO, JMP and IDB developed a first draft of the environmental questionnaire. All authors participated in the expert meeting, contributed to synthesising the results and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Electronic supplementary material

12966_2009_252_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Items for eight questionnaires in relation to physical activity used in Europe. Table presenting the full list of items from all eight questionnaires, categorised per theme. (PDF 550 KB)

12966_2009_252_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Long measure of environmental perceptions: active travel and physical activity. ALPHA environmental questionnaire (long form) in English. (PDF 93 KB)

12966_2009_252_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Short measure of environmental perceptions: active travel and physical activity. ALPHA environmental questionnaire (short form) in English. (PDF 53 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Spittaels, H., Foster, C., Oppert, JM. et al. Assessment of environmental correlates of physical activity: development of a European questionnaire. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 6, 39 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-39