Abstract

During the last decade, there has been a rapid increase in development of instruments to measure parent food practices. Because these instruments often measure different constructs, or define common constructs differently, an evaluation of these instruments is needed. A systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify existing measures of parent food practices and to assess the quality of their development. The initial search used terms capturing home environment, parenting behaviors, feeding practices and eating behaviors, and was performed in October of 2009 using PubMed/Medline, PsychInfo, Web of knowledge (ISI), and ERIC, and updated in July of 2012. A review of titles and abstracts was used to narrow results, after which full articles were retrieved and reviewed. Only articles describing development of measures of parenting food practices designed for families with children 2-12 years old were retained for the current review. For each article, two reviewers extracted data and appraised the quality of processes used for instrument development and evaluation. The initial search yielded 28,378 unique titles; review of titles and abstracts narrowed the pool to 1,352 articles; from which 57 unique instruments were identified. The review update yielded 1,772 new titles from which14 additional instruments were identified. The extraction and appraisal process found that 49% of instruments clearly identified and defined concepts to be measured, and 46% used theory to guide instrument development. Most instruments (80%) had some reliability testing, with internal consistency being the most common (79%). Test-retest or inter-rater reliability was reported for less than half the instruments. Some form of validity evidence was reported for 84% of instruments. Construct validity was most commonly presented (86%), usually with analysis of associations with child diet or weight/BMI. While many measures of food parenting practices have emerged, particularly in recent years, few have demonstrated solid development methods. Substantial variation in items across different scales/constructs makes comparison between instruments extremely difficult. Future efforts should be directed toward consensus development of food parenting practices constructs and measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The role of the home environment in shaping a child’s diet and growth is an area of increasing interest, particularly among those working in child obesity prevention and treatment. The home environment has significant influence on child socialization [1], including adoption of eating behaviors [2]. This is particularly true for younger children (2-12 years old) given their limited autonomy and dependence on adult caretakers, who influence dietary intake and eating behaviors through the foods they provide as well as the social environment they create [3].

Parent food practices and feeding style represent a large component of parent behaviors that influence child diet and/or weight. Parent food practices are the specific techniques or behaviors used by parents to influence children’s food intake [4]. Traditionally, food practice constructs have included pressure to eat, restriction, monitoring of the child’s food intake, or the use of rewards for food consumption. More recently, constructs have been expanded to include parent food modeling, family mealtime environments, food preparation practices, involvement of children in food planning and preparation, and control allowed to children over when, where, what and how much they eat. While food practices are specific behaviors or actions, they are often used to categorize parent feeding style [5]. A parent’s feeding style reflects the emotional climate in which these practices occur, or the balance between demanding versus responsive feeding practices [6].

Reviews of family environmental correlates have found fairly consistent associations between child fruit and vegetable consumption and parent food practices such as dietary modeling, food rules, and encouragement [7–9]. However, these reviews have also highlighted gaps in the literature with regard to measurement. How constructs are defined and measured is highly variable across studies, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions. Additionally, studies tend to assess only a limited number of constructs; thus hampering efforts to understand the relative importance of factors and how they might interact. While there have been two recent reviews on measurement of home food availability and accessibility [10, 11], there has not been a similar review focused on measurement of the parent behaviors that influence child diet.

This paper addresses this gap in the literature by presenting results from a comprehensive, systematic review designed to identify and evaluate instruments or specific scales assessing parent food practices. It captures the full array of parental food practices thought to shape the sociocultural food environment of the home in an attempt to bring some order to a field of measurement that has become increasingly complex and confusing.

Methods

This review was conducted in two phases (depicted in Figure 1), beginning with an extensive systematic review of the literature to identify factors within the home environment hypothesized to relate to children’s diet and/or eating behaviors. During this first phase, both social and physical characteristics of the home environment and any evidence of their relationship to child diet, eating behaviors, or weight were explored. This initial review was conducted as part of a larger study to identify potential constructs and items for consideration in the development of a comprehensive measure of the home food environment (known as the Home Self-administered Tool for Environmental assessment of Activity and Diet, or HomeSTEAD, R21CA134986). The search terms used and inclusion and exclusion criteria employed reflect this goal. During the second phase, results of the initial review were used to identify articles describing development of instruments assessing parent food practices.

The initial systematic literature review was conducted in October of 2009 using four search engines: PubMed/Medline, PsychInfo, Web of knowledge (ISI), and ERIC. Search terms were identified to capture the following topic areas: (1) home environment or parent behaviors and (2) feeding practices, dietary habits, or eating behaviors. (A detailed description of search terms is available in Additional file 1). No limits were placed on date of publication, but articles had to be in English.

Titles and abstracts were reviewed to narrow results. Percent agreement between reviewers (AV, RT, MB) based on a 5% sample of search results ranged between 93-95%. Disagreements were discussed by all authors; discrepancies were resolved via consensus; and inclusion/exclusion criteria were refined. Following completion of the title and abstract review, full articles were retrieved and reviewed (by either AV or RT) to determine whether or not the paper met the full inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

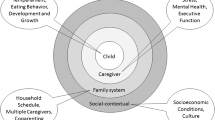

During the first phase, inclusion criteria specified that the methods section had to describe the measurement of physical and/or social-cultural characteristics of the home environment related to diet and/or eating behaviors in children aged 2-18 years. A content map (Figure 2) based on the ANGELO framework [12] guided the review and ensured inclusion of all relevant topics. The ANGELO framework identifies four types of environments – physical, socio-cultural, political, and economic – which were then conceptualized and defined very specifically to factors coming from within the home environment. The economic environment is often captured by assessing household income, parent occupation, parent education, and similar demographic variables. Identifying demographic surveys was not the focus of this review; therefore, the economic environment was viewed as outside the scope. Additional constructs outside the scope of this review included: individual level determinants of behavior (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, barriers, food security, acculturation), child eating behaviors (e.g., picky eating), and parent or child dietary intake, food expenditures, time use, body image, and factors not specific to the home (e.g., restaurant meals, purchasing behaviors). While these factors may influence the home food environment, they are not a direct measure of that environment.

Articles were also excluded at this stage if they were not peer reviewed (e.g., editorials and dissertations), if they would not aid in the identification of close-ended items (literature reviews, qualitative studies, case reports), or if they referenced use of an existing measure and offered no further development. In cases where existing and relevant instruments were reused, reviewers verified that the original measure development article had been retained in the original search. Articles could also be excluded if the original measure could not reasonably be obtained (e.g., surveys administered in another language with no translation of items provided within the article, articles published before 1995 that provided insufficient detail to recreate items).

In the second phase, additional selection criteria were added to narrow results to articles that described development and/or evaluation of an instrument assessing parent food practices in families with 2-12 year old children. Parent food practices was defined broadly, based on the original content map, to include constructs related to the home’s social, cultural and political environment around food. Measures of the home’s physical environment (food preparation space, food consumption areas, food availability and accessibility) were eliminated, but have been described elsewhere [10, 11].

Articles had to contain details regarding instrument development and/or evaluation. This could include steps such as developing items based on formative data, using cognitive interviews to assess item clarity, engaging experts to evaluate content coverage, and at least one method of reliability or validity testing (e.g. test-retest reliability, internal validity, construct validity, etc.). Measures also had to include at least one relevant scale or theory-generated category of items.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction form and quality assessment protocol were developed to facilitate the full appraisal of each measure. While quality assessment protocols of patient-reported outcomes do exist [13–16], review and pilot testing of these tools with papers from this review showed that modifications would be required. Therefore, a new protocol was developed based on common elements from existing protocols and DeVellis’ scale development standards [17]. This process was fully piloted by all authors to ensure accuracy of reporting. Percent agreement between reviewers across items was, on average 83.4% (range: 49.1-100). Additionally, any differences in scoring were discussed until agreement on a final score could be reached. Data extracted, included:

-

General descriptive characteristics of the measurement tool: reference, name of measure, purpose, total number of items

-

Details about sample used for development: sample size, age range and gender (of children), race/ethnicity, SES, country, completed by parent/child/both, subject burden, translation and/or testing in additional populations

-

Content: theory or conceptual model employed, list of scales/categories assessed, number of items in each scale/category

Quality evaluated for the following six key elements:

-

Conceptualization of instrument purpose: Instruments were scored 1-4 depending on how clearly the paper conceptualized the purpose of the tool and defined constructs intended to be measured (4 = strongly agree, concepts are named and clearly defined, 3 = agree, concepts are named and generally described, 2 = disagree, concepts only named, but not defined, and 1 = strongly disagree, concepts are not clearly named or defined). Additionally, reviewers captured whether or not a theory or conceptual model helped inform this conceptualization (yes/no).

-

Development of item pool: Instruments were scored on how systematic the developers’ process was for developing a pool of potential items, taking into consideration the use of multiple methods (e.g., pulling items from existing instruments, consulting expert opinion, extrapolating from qualitative data, and extracting from the literature) and an iterative process. Scores ranged from 1-3 where 3 = fully systematic processes were used, 2 = systematic process were weak or only used for pieces (but not whole instrument), and 1 = no systematic process used/reported.

-

Refinement of item pool: Reviewers extracted information about the methods employed to refine the item pool (e.g., expert review, pilot testing or cognitive interviews with draft instrument, assessment of item performance, and use of exploratory factor analysis. When applicable and available, factor loading were recorded so that they could be compared against generally recognized statistical standards to retain only items with factor loading greater than 0.4 and to address any items with cross-loadings greater than 0.32 [18].

-

Reliability: To capture evidence of reliability, reviewers extracted information regarding the evaluation of test-retest, inter-rater, and/or internal consistency testing. Results of test-retest and inter-rater reliability testing, which generally present correlation analysis, were extracted so that results could be compared against generally accepted standards where 0-0.2 indicates poor agreement, 0.3-0.4 indicates fair agreement, 0.5-0.6 indicates moderate agreement, 0.7-0.8 indicates strong agreement, and >0.8 indicates almost perfect agreement [19]. Results of internal consistency, which generally report Cronbach’s alpha, were extracted so that results could be compared against generally accepted standards where 0.6-0.7 is questionable (but often considered sufficient in exploratory analyses), 0.7-0.8 is acceptable, 0.8-0.9 is good, and ≥0.9 is excellent [20].

-

Validity: Reviewers extracted information about three types of validity: construct validity, structural validity, and criterion validity. Construct validity was defined as evidence that the new scale(s) “behaves the way that the construct it purports to measure should behave with regard to established measures of other constructs.” (DeVellis, pg. 46) This can include evidence of associations/correlations between the new scale(s) and established measures of general parenting practices, child dietary intake or eating habits, and/or child weight. Evaluation of construct validity could employ simple correlations or t-tests, or more complex methods like regression models. While correlations ≥0.3 are considered acceptable, the significance of results must be interpreted in light of the underlying theory. Evidence of structural validity, specifically results from confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), were extracted so that results could be compared against generally accepted cutoffs for “acceptable” fit indices: maximum likelihood-based Tucker-Lewis Index, Bollen’s Delta, Comparative Fit Index, Relative Centrality Index, and Gamma Hat ≥0.95, McDonald’s Centrality Index ≥0.90, Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual ≥0.08, and Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation ≤0.06 [21]. Evidence of criterion validity was also extracted, generally assessed by correlational analysis between the new scale and a gold standard. The criterion used for the gold standard in this review had to be an objective assessment of food parenting practices (e.g., observation protocols completed by trained research staff).

-

Responsiveness: Evidence of responsiveness was also extracted. Responsiveness testing is usually conducted using Effect Size statistics or Standardized Response Means (with values greater than 0.5 considered moderate [22]) or by the Reliable Change Index (with 1.96 considered as a minimally important difference [23]).

An updated literature search was conducted in July 2012 to identify additional measures published since the original search. Given the broad scope of the original search, terms were refined to focus the search on food parenting practices (using the diversity of terms uncovered during the original search) and specifically articles describing the development of measures.

Results

Results from the four search engines were combined and duplicates were identified and removed, resulting in 28,378 unique titles. Review of titles and abstracts narrowed the search to 1,352 articles, and full articles were located and retrieved for all but six. The initial selection criteria narrowed the search to 242 articles; the additional criteria added in the second phase further narrowed the pool to 74 articles; and a review of citations identified 8 additional papers. These 82 articles described development of 57 unique instruments. The updated search identified 18 additional articles, 14 of which represented new instruments. Table 1 provides a description of each instrument identified and Table 2 describes the development processes employed.

Among the food parenting practice questionnaires included in this review, final surveys had between 6 and 221 items (44 items on average). While all instruments had at least one relevant scale or categorical grouping of items to assess parent food practices, items within these scales or categories represented less than half of the items in the instrument. These instruments had between 2 and 76 relevant items (19 relevant items on average) and anywhere between 1 and 12 relevant scales or categories (3 to 4 on average). As described in Table 1, the constructs measured varied widely from one instrument to another. Often instruments focused on measuring either controlling feeding practices or supportive and encouraging feeding practices.

Conceptualization of instrument’s purpose

The terms used to describe what the instruments were intended to measure varied, in part, on the background from which the instrument arose. In addition to parent food practices, common terms included: parent-child feeding practices, feeding strategies, feeding style, feeding dimensions, feeding relationship, mealtime environment, mealtime actions, mealtime interactions, parent-child mealtime behaviors, food socialization practices, home food environment, amongst others. Each of these terms has a slightly different definition; however, all of the instruments included items that measured parent food practices. Despite differences in terms, 87% did conceptualize and define what they intended to measure, with 35 instruments receiving the maximum score of 4 and 27 instruments receiving a 3 for conceptualization. Just under half (33 of 71) noted a theoretical basis for the development of their instrument. More commonly referenced theories included: Social Cognitive Theory (n = 12) [43, 46, 61, 62, 91, 93, 98, 102],[104, 107, 114, 121], Social Ecologic Framework (n = 3) [97, 98, 101], Theory of Planned Behavior (n = 3) [35, 74, 98], Social Learning Theory (n = 2) [37, 82], Costanzo and Woody’s Domain Specific Parenting or Baumrind’s Parenting Styles (n = 4) [6, 52, 64, 123], and Satter’s model of the feeding relationship (n = 3) [27, 29, 113].

Development of item pool

The processes used to develop a pool of items varied widely. Only 14 (20%) received the maximum score of 3, indicating a fully systematic process was employed. Common methods employed for item development included: pulled or modified items from existing instruments (n = 44), extrapolation from qualitative formative data such as focus groups or interviews (n = 36), created items based on a review of the literature (n = 22), expert guidance (n = 19), or some combination of methods (n = 33). Seven instruments had no description regarding how items were created.

Refinement of item pool

About one third (n = 24) of the instruments identified in this review did not report any attempts to refine the pool of items once created. Among those who did attempt to refine their pool of items, factor analysis was the most commonly used method (n = 36). Those who employed factor analyses generally used widely accepted criteria for cut-offs for factor loadings and cross loadings. Only 16 instruments had items reviewed by experts to assess content validity, and only 30 piloted the instrument or conducted cognitive interviews to assess clarity of items and face validity. Item performance was also noted as a means to reduce the item pool for 7 instruments.

Reliability

Some form of reliability was reported for a majority of instruments (n = 57 or 80%). Internal consistency was the most common form of reliability reported (n = 56). Generally those that employed such methods retained only those scales that met generally established cut-off criteria with 38 reporting Cronbach’s alphas of at least 0.6 or higher. None of these 38 instruments had alphas greater than 0.9 for all scales, only 5 had alphas consistently above 0.8, and an additional 23 had alphas consistently above 0.7. Test-retest was reported for 27 instruments, typically using a 1-3 week interval. The two notable exceptions were the GEMS’ Diet-Related Psychosocial Questionnaire [69], which administered test-retest over a 12-week period (during which time there was also an intervention delivered); and the Behavioral Pediatrics Feeding Assessment Scale [31], which administered test-retest over a 2 year interval. Correlations reported for test-retest were generally acceptable (>0.6) for most scales within a given instrument. However, when looking at test-retest correlations of all scales on a given instrument only 5 had correlations for all scales above 0.8; 6 additional had correlations >0.7; and 5 more had correlations >0.6. Inter-rater reliability was reported for 6 instruments, but only 1 instrument reported that all correlations were >0.8, the remaining 5 included correlations less than 0.6 for at least one scale.

Validity

The majority of instruments (n = 61 or 86%) reported some type of validity evidence. Construct validity was by far the most common type of validity evidence evaluated (n = 59), often testing for relationships between food parenting practices and child diet or child weight. Most instruments had one or more scales that were significantly associated with one of these outcomes; however, correlations were generally in the range of 0.15-0.45. While all papers including this type of evidence were given credit for evaluating construct validity, these tests were not always presented as construct validity within the articles. Confirmatory factor analysis was reported for only 10 instruments. Those that did attempt to explore structural validity were generally successful with only minor modifications to their original model. Only two studies attempted to establish criterion validity.

Responsiveness

The Family Eating and Activity Habits Questionnaire [37] was the only paper that formally assessed the instruments’ responsiveness to treatment results. The questionnaire was administered to families taking part in a weight loss program both at baseline and follow-up. Changes in questionnaire scores as well as changes in weight were observed in the intervention group, and weight loss in the child was highly correlated with improvement in the questionnaire score.

Completeness of development process

Ideally, instrument development would involve all 6 components described thus far: (1) clear conceptualization of what the instrument is intended to measure, (2) systematic process for developing item pool, (3) refinement of the item pool (through at least one method: factor analysis, expert review, cognitive interviews, and/or piloting), (4) some type of reliability testing (inter-rater, test-retest, and/or internal consistency), (5) at least one type of validity testing, and (6) responsiveness or stability testing. On average, instruments reported only 2 or 3 of these 6 steps (range: 0 to 4).

Discussion

In the current review, 71 instruments were identified that included assessment of parent food practices. The quality of processes used and reported for instrument development varied widely, but there are instruments that demonstrate reasonably thorough development work. The quality assessment of the 71 instruments in this review highlights many key lessons that should inform future research in the areas of conceptualization of constructs, development and refinement of the item pool, collection of multiple types of reliability and validity evidence, and planning for responsiveness or stability testing.

Conceptualization of constructs

Parent food practices is a rapidly growing area of research that would benefit greatly from a common conceptual model. The content map (Figure 2) represents an initial effort to capture relevant constructs that should be included in this conceptual model. It served as a useful guide for the current review and may help inform future work to develop a conceptual model. Consensus is required in order to develop a clear conceptual model including an indication of what constructs should be included and how those constructs should be defined. The current lack of consensus has resulted in scales from different instruments that may share similar names, but include items measuring very different behaviors. Further, other instruments may include similar items, but employ different names for their scales. For example, the Restriction subscale from the Child Feeding Questionnaire [52] includes items about ensuring the child does not eat too many sweets or high fat foods and items about guiding and regulating child’s intake of certain foods – both of which reflect how “restriction” is typically defined. However, this subscale also includes items regarding offering sweets as a reward for good behavior, which other measures call “instrumental feeding” [65]. Researchers working in this field need consensus and a clear conceptual model based on current knowledge. Future research can then expand upon or clarify components of the model.

The use of theory to guide instrument development helps ensure clear conceptualization of all relevant constructs. Unfortunately, only half of developers noted a theoretical basis for their instruments. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [124] and the Social Ecologic Framework [125, 126] were two of the most commonly referenced theories, both of which recognize the influence that the environment, and the shared environment in particular, has on behavior. A number of instruments originated from family psychology, using theories about Social Learning Theory [127], Parenting Dimensions [128–130], and Domain Specific Parenting [131] to guide development of their instruments. These theories generally recognize that parents play a central role in the socialization of their children and hence the behaviors that a child adopts, including eating behaviors. All of the theories provided useful guidance to instrument development, and should be considered in efforts to develop a conceptual model for parent food practices.

Development and refinement of the item pool

Ideally, development and refinement of the item pool uses a systematic approach that involves multiple methods and allows for multiple iterations. Consulting the current literature is a good starting point, but less than one third of instruments reported reviewing the literature as part of their process. Many instruments reported pulling items from existing instruments, but it is unknown how systematically existing instruments were reviewed before selecting which instruments and items to use for the new measure. Development of a new measure should also address gaps in measurement, creating items and scales for constructs not being measured by current instruments. Informed processes are needed to guide creation of new questions. Qualitative data (e.g., focus groups and interviews) can provide such a resource, but less than half of instruments reported drawing on such data sources. Once an initial item pool is created, it is also important to evaluate and refine that item pool; however, over a third of instruments reported no details on item refinement. Among those that did, factor analysis was the most common strategy employed. Expert review, cognitive interviews and piloting are important steps for ensuring complete content coverage and inclusion of items that are easily interpreted by the target audience. However, very few instruments reported assessment of content or face validity. The development article for the Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire [87] provides a useful example of a thorough and iterative process combining multiple strategies to generate and refine an item pool. To create an initial item pool, these researchers drew items from most widely used instruments, adapted items from adult measures where no existing items existed and reviewed the literature to gather information about additional constructs. The original item pool was piloted and factor analysis used to identify constructs needing additional items. Then, open-ended questions were given to another sample of parents to help generate these additional items. Future researchers interested in instrument development should aim to adopt similar methodologies and incorporate multiple strategies into their own plans for developing and refining the item pool for their new instruments.

Reliability and validity evidence

While almost all instruments received credit for performing some evaluation of reliability (80%) or validity (86%), there was clear reliance on more statistical approaches using data collected from a single time point for supplying such evidence. For reliability, many instruments presented only a Cronbach’s alpha. While this provides information on how well items within a scale group together, it does not provide evidence of repeatability. Assessment of test-retest and inter-rater reliability provides this type of evidence, but requires more investment in data collection. Not surprisingly, few instruments included these latter types of evaluation. Similarly, most validity evidence came from assessment of construct validity. Structural validity and criterion validity require greater investment in data collection to administer the instrument in multiple samples or to collect a gold standard measure. Use of these latter types of validity was limited. A thorough assessment of reliability and validity should include multiple strategies for each, which will require researchers to devote more time to instrument development by collecting data across multiple time points or in multiple samples or incorporating use of a gold standard.

Responsiveness testing

The area of instrument development that clearly needs the most attention is instrument responsiveness. Researchers seeking to evaluate interventions need evidence regarding the level of change that these instruments are able to detect. This type of information is essential when trying to calculate power and sample size needed for a study. While many of these instruments have indeed been used in studies to evaluate interventions, responsiveness testing is almost never reported as part of the development.

Additional issues

Another important consideration when selecting an instrument is its relevance for the target population. The feeding relationship changes as children get older, and hence the feeding practices parents employ change as well. At younger ages, children are more dependent on their parents to provide food choices. As they get older, they become more independent and peers are thought to exert a greater influence on eating habits [132], which may in turn influence the feeding approaches parents employ. All of the instruments included in this review were developed for families with children between the ages of 2 and 12 years old. Similarly, parent food practices may vary across different cultural groups [44, 51]. Some practices may appear to be detrimental to healthy eating habits in certain populations, but those same practices are found to be protective in others. For this reason, Table 1 describes the population in which each instrument was tested.

Limitations

Authors of this review provided a comprehensive inventory and assessment of existing measures of parent food practices. However, the current review is limited to instruments developed for families with children 2-12 years old. Additional instruments that were developed for families with adolescent children are not included. We limited this review to younger children because the parents and the home environment are the predominant influence on child eating behaviors at this age. Similarly, this review is limited to articles written in English. While it includes instruments that were developed in other languages, there are additional non-English instruments that have undoubtedly been left out of the current inventory. The results focus on presenting the primary development articles for each of the identified instruments; however, many of these instruments have been used in later studies with different populations. During the review process, 244 articles were identified that described studies in which existing instruments were used. Some of these may provide additional information about construct validity (e.g., association with child diet or weight), but were not included or summarized here. However, articles in which there was clear development work to adapt and evaluate scales for new populations are captured in Table 1. Also, no attempt was made to provide an overall quality scores for each instrument. To be truly informative, a scoring rubric would need to take into account not just attempts to complete the various development steps, but also the appropriateness of tests used, and the significance of the outcomes across factors measured within an instrument. Such a scoring tool is expected to be complex and is not yet available at the time of writing. Therefore, the authors have summarized the development work that has been done, the reliability and validity evidence reported, and well-accepted criteria for assessing those results. Readers are thus able to judge for themselves the strength of the evidence in light of other factors.

Conclusions

This review was able to identify 71 different measures of parent food practices. However, these existing instruments measure a variety of different constructs. Additionally, the rigor with which they were developed varied widely. Ideally, instrument development and evaluation are multi-staged processes that require time and patience. Researchers or practitioners who do not have the resources to dedicate to instrument development should be encouraged to look for existing instruments that measure the specific constructs needed for their study. Future work should focus on further evaluation of appropriate instruments where possible. Undoubtedly, new instruments will need to be developed; however, this future development work should consider the lessons learned from the current review and to consider all stages of development needed to create a valid and reliable measure.

References

Maccoby E: The role of parents in the socialization of children: an historical overview. Dev Psychol. 1992, 28 (6): 1006-1017.

Patrick H, Nicklas TA: A review of family and social determinants of children's eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005, 24 (2): 83-92.

Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T: Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 12 (2): 1-17.

Blissett J: Relationships between parenting style, feeding style and feeding practices and fruit and vegetable consumption in early childhood. Appetite. 2011, 57 (3): 826-831.

Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski DA: Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr Rev. 2008, 66 (3): 123-140.

Hughes SO, Power TG, Orlet Fisher J, Mueller S, Nicklas TA: Revisiting a neglected construct: parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite. 2005, 44 (1): 83-92.

Pearson N, Biddle SJ, Gorely T: Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12 (2): 267-283.

van der Horst K, Oenema A, Ferreira I, Wendel-Vos W, Giskes K, van Lenthe F, Brug J: A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ Res. 2007, 22 (2): 203-226.

Rasmussen M, Krolner R, Klepp KI, Lytle L, Brug J, Bere E, Due P: Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006, 3: 22.

French SA, Shimotsu ST, Wall M, Gerlach AF: Capturing the spectrum of household food and beverage purchasing behavior: a review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (12): 2051-2058.

Bryant M, Stevens J: Measurement of food availability in the home. Nutr Rev. 2006, 64 (2 Pt 1): 67-76.

Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F: Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999, 29 (6 Pt 1): 563-570.

Valderas JM, Ferrer M, Mendivil J, Garin O, Rajmil L, Herdman M, Alonso J: Development of EMPRO: a tool for the standardized assessment of patient-reported outcome measures. Value Health. 2008, 11 (4): 700-708.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Stratford PW, Alonso J, Patrick DL, Bouter LM, de Vet HC: Protocol of the cosmin study: consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 2.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health: Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006, 4: 79.

Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust: Assessing health status and quality of life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11: 193-205.

DeVellis R: Scale Development Theory and Applications. 2003, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2

Costello AB, Osborne J: Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. 2005, 10 (7).

Landis JR, Koch GG: The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977, 33 (1): 159-174.

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC: Multivariate Data Analysis. 1998, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall International, Inc., 5

Hu L, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999, 6: 1-55.

Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. 1988, New Jersey: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc., 2

Jacobson NS, Truax P: Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991, 59: 12-19.

Jensen EW, James SA, Boyce WT, Hartnett SA: The family routines inventory: development and validation. Soc Sci Med. 1983, 17 (4): 201-211.

Boyce WT, Jensen EW, James SA, Peacock JL: The family routines inventory: theoretical origins. Soc Sci Med. 1983, 17 (4): 193-200.

Stanek K, Abbott D, Cramer S: Diet quality and the eating environment of preschool children. J Am Diet Assoc. 1990, 90 (11): 1582-1584.

Seagren JS, Terry RD: WIC Female Parents’ Behavior and Attitudes Toward Their Children’s Food Intake - Relationship to Children's Relative Weight. J Nutr Educ. 1991, 23 (5): 223-230.

Sherman JB, Alexander MA, Clark L, Dean A, Welter L: Instruments measuring maternal factors in obese preschool children. West J Nurs Res. 1992, 14 (5): 555-569. discussion 569-575

Davies WH, Ackerman LK, Davies CM, Vannatta K, Noll RB: About Your Child’s Eating: factor structure and psychometric properties of a feeding relationship measure. Eat Behav. 2007, 8 (4): 457-463.

Davies CM, Noll RB, Davies WH, Bukowski WM: Mealtime interactions and family relationships of families with children who have cancer in long-term remission and controls. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993, 93 (7): 773-776.

Crist W, McDonnell P, Beck M, Gillespie CT, Barrett P, Matthews J: Behavior at Mealtimes and the Young Child with Cystic Fibrosis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1994, 15 (3): 157-161.

Sallis JF, Broyles SL, Frank-Spohrer G, Berry CC, Davis TB, Nader PR: Child’s home environment in relation to the mother’s adiposity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995, 19 (3): 190-197.

Koivisto UK, Sjoden PO: Reasons for rejection of food items in Swedish families with children aged 2-17. Appetite. 1996, 26 (1): 89-103.

Humphry R, Thigpen-Beck B: Caregiver Role: Ideas about feeding infants and toddlers. Occup Ther J Res. 1997, 17 (4): 237-263.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P: Personal and family determinants of dietary behavior in adolescents and their parents. Psychol Health. 2000, 15 (6): 751-770.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Van Oost P: Family members' influence on decision making about food: differences in perception and relationship with healthy eating. Am J Health Promot. 1998, 13 (2): 73-81.

Golan M, Weizman A: Reliability and validity of the Family Eating and Activity Habits Questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998, 52 (10): 771-777.

Golan M, Fainaru M, Weizman A: Role of behaviour modification in the treatment of childhood obesity with the parents as the exclusive agents of change. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998, 22 (12): 1217-1224.

Hupkens CL, Knibbe RA, Van Otterloo AH, Drop MJ: Class differences in the food rules mothers impose on their children: a cross-national study. Soc Sci Med. 1998, 47 (9): 1331-1339.

Fisher JO, Birch LL: Restricting access to palatable foods affects children’s behavioral response, food selection, and intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999, 69 (6): 1264-1272.

Carper JL, Orlet Fisher J, Birch LL: Young girls’ emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite. 2000, 35 (2): 121-129.

Monnery-Patris S, Rigal N, Chabanet C, Boggio V, Lange C, Cassuto DA, Issanchou S: Parental practices perceived by children using a French version of the Kids’ Child Feeding Questionnaire. Appetite. 2011, 57 (1): 161-166.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Rittenberry L, Cosart C, Owens E, Hebert D, Moor C: Socioenvironmental influences on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption as reported by parents: reliability and validity of measures. Public Health Nutr. 2000, 3 (3): 345-356.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Owens E, De MC, Rittenberry L, Olvera N, Resnicow K: Ethnic differences in social correlates of diet. Health Educ Res. 2002, 17 (1): 7-18.

Humenikova L, Gates GE: Social and physical environmental factors and child overweight in a sample of American and Czech school-aged children: a pilot study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008, 40 (4): 251-257.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M: Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: findings from Project EAT. Prev Med. 2003, 37 (3): 198-208.

Neumark-Stzainer D, Story M, Ackard DM, Moe J, Perry C: Family meals among adolescents: Findings from a pilot study. J Nutr Educ. 2000, 32 (6): 335-340.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M, Fulkerson JA: Are family meal patterns associated with disordered eating behaviors among adolescents?. J Adolesc Health:. 2004, 35 (5): 350-359.

Ross LT, Hill EM: The family unpredictability scale: reliability and validity. J Marriage Fam. 2000, 62: 549-562.

Baughcum AE, Powers SW, Johnson SB, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Jain A, Whitaker RC: Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2001, 22 (6): 391-408.

Seth JG, Evans AE, Harris KK, Loyo JJ, Ray TC, Spaulding C, Gottlieb NH: Preschooler feeding practices and beliefs: differences among Spanish- and English-speaking WIC clients. Fam Community Health. 2007, 30 (3): 257-270.

Birch LL, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Markey CN, Sawyer R, Johnson SL: Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: a measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite. 2001, 36 (3): 201-210.

Johnson SL, Birch LL: Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics. 1994, 94 (5): 653-661.

Haycraft EL, Blissett JM: Maternal and paternal controlling feeding practices: reliability and relationships with BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008, 16 (7): 1552-1558.

Anderson CB, Hughes SO, Fisher JO, Nicklas TA: Cross-cultural equivalence of feeding beliefs and practices: the psychometric properties of the child feeding questionnaire among blacks and hispanics. Prev Med. 2005, 41 (2): 521-531.

Kaur H, Li C, Nazir N, Choi WS, Resnicow K, Birch LL, Ahluwalia JS: Confirmatory factor analysis of the child-feeding questionnaire among parents of adolescents. Appetite. 2006, 47 (1): 36-45.

Boles RE, Nelson TD, Chamberlin LA, Valenzuela JM, Sherman SN, Johnson SL, Powers SW: Confirmatory factor analysis of the child feeding questionnaire among low-income african american families of preschool children. Appetite. 2010, 54 (2): 402-405.

Geng G, Zhu Z, Suzuki K, Tanaka T, Ando D, Sato M, Yamagata Z: Confirmatory factor analysis of the child feeding questionnaire (CFQ) in japanese elementary school children. Appetite. 2009, 52 (1): 8-14.

Corsini N, Danthiir V, Kettler L, Wilson C: Factor structure and psychometric properties of the child feeding questionnaire in australian preschool children. Appetite. 2008, 51 (3): 474-481.

Kasemsup R, Reicks M: The relationship between maternal child-feeding practices and overweight in Hmong preschool children. Ethn Dis. 2006, 16 (1): 187-193.

Cullen KW, Baranowski T, Rittenberry L, Cosart C, Hebert D, de Moor C: Child-reported family and peer influences on fruit, juice and vegetable consumption: reliability and validity of measures. Health Educ Res. 2001, 16 (2): 187-200.

Tibbs T, Haire-Joshu D, Schechtman KB, Brownson RC, Nanney MS, Houston C, Auslander W: The relationship between parental modeling, eating patterns, and dietary intake among African-American parents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001, 101 (5): 535-541.

Moens E, Braet C: Predictors of disinhibited eating in children with and without overweight. Behav Res Ther. 2007, 45 (6): 1357-1368.

Tiggemann M, Lowes J: Predictors of maternal control over children’s eating behaviour. Appetite. 2002, 39 (1): 1-7.

Wardle J, Sanderson S, Guthrie CA, Rapoport L, Plomin R: Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. 2002, 10 (6): 453-462.

Clark HR, Goyder E, Bissell P, Blank L, Walters SJ, Peters J: A pilot survey of socio-economic differences in child-feeding behaviours among parents of primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11 (10): 1030-1036.

Sleddens EF, Kremers SP, De Vries NK, Thijs C: Relationship between parental feeding styles and eating behaviours of Dutch children aged 6-7. Appetite. 2010, 54 (1): 30-36.

Bourcier E, Bowen DJ, Meischke H, Moinpour C: Evaluation of strategies used by family food preparers to influence healthy eating. Appetite. 2003, 41 (3): 265-272.

Cullen KW, Klesges LM, Sherwood NE, Baranowski T, Beech B, Pratt C, Zhou A, Rochon J: Measurement characteristics of diet-related psychosocial questionnaires among African-American parents and their 8- to 10-year-old daughters: results from the Girls’ health Enrichment Multi-site Studies. Prev Med. 2004, 38 (Suppl): S34-S42.

Melgar-Quinonez HR, Kaiser LL: Relationship of child-feeding practices to overweight in low-income Mexican-American preschool-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004, 104 (7): 1110-1119.

Kaiser LL, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Lamp CL, Johns MC, Harwood JO: Acculturation of Mexican-American mothers influences child feeding strategies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001, 101 (5): 542-547.

Vereecken CA, Keukelier E, Maes L: Influence of mother’s educational level on food parenting practices and food habits of young children. Appetite. 2004, 43 (1): 93-103.

Vereecken C, Legiest E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L: Associations between general parenting styles and specific food-related parenting practices and children's food consumption. Am J Health Promot. 2009, 23 (4): 233-240.

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Klepp KI, Due P, Rodrigo CP, de Almeida M, Wind M, Krolner R, Sandvik C, Brug J: Reliability and validity of a questionnaire to measure personal, social and environmental correlates of fruit and vegetable intake in 10-11-year-old children in five European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8 (2): 189-200.

Horodynski MA, Stommel M: Nutrition education aimed at toddlers: an intervention study. Pediatr Nurs. 2005, 31 (5): 364, 367-372.

Hughes SO, Anderson CB, Power TG, Micheli N, Jaramillo S, Nicklas TA: Measuring feeding in low-income African-American and Hispanic parents. Appetite. 2006, 46 (2): 215-223.

Hughes SO, Cross MB, Hennessy E, Tovar A, Economos CD, Power TG: Caregiver's Feeding Styles Questionnaire: establishing cutoff points. Appetite. 2012, 58 (1): 393-395.

Tripodi A, Daghio MM, Severi S, Ferrari L, Ciardullo AV: Surveillance of dietary habits and lifestyles among 5-6 year-old children and their families living in Central-North Italy. Soz Praventivmed. 2005, 50 (3): 134-141.

Vereecken CA, Van Damme W, Maes L: Measuring attitudes, self-efficacy, and social and environmental influences on fruit and vegetable consumption of 11- and 12-year-old children: reliability and validity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005, 105 (2): 257-261.

Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell N, Baquero B, Duerksen S: Is parenting style related to children’s healthy eating and physical activity in Latino families?. Health Educ Res. 2006, 21 (6): 862-871.

Larios SE, Ayala GX, Arredondo EM, Baquero B, Elder JP: Development and validation of a scale to measure Latino parenting strategies related to children’s obesigenic behaviors: the parenting strategies for eating and activity scale (PEAS). Appetite. 2008, 52 (1): 166-172.

Ogden J, Reynolds R, Smith A: Expanding the concept of parental control: a role for overt and covert control in children’s snacking behaviour?. Appetite. 2006, 47 (1): 100-106.

Brown R, Ogden J: Children’s eating attitudes and behaviour: a study of the modelling and control theories of parental influence. Health Educ Res. 2004, 19 (3): 261-271.

Brown KA, Ogden J, Vogele C, Gibson EL: The role of parental control practices in explaining children’s diet and BMI. Appetite. 2008, 50 (2–3): 252-259.

de Moor J, Didden R, Korzilius H: Parent-reported feeding and feeding problems in a sample of Dutch toddlers. Early Child Dev Care. 2007, 177 (3): 219-234.

Gray VB, Byrd SH, Cossman JS, Chromiak JA, Cheek W, Jackson G: Parental attitudes toward child nutrition and weight have a limited relationship with child’s weight status. Nutr Res. 2007, 27 (9): 548-558.

Musher-Eizenman D, Holub S: Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007, 32 (8): 960-972.

Melbye EL, Ogaard T, Overby NC: Validation of the comprehensive feeding practices questionnaire with parents of 10-to-12-year-olds. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011, 11: 113.

Reinaerts E, de Nooijer J, Candel M, de Vries N: Explaining school children’s fruit and vegetable consumption: the contributions of availability, accessibility, exposure, parental consumption and habit in addition to psychosocial factors. Appetite. 2007, 48 (2): 248-258.

Stanton CA, Green SL, Fries EA: Diet-specific social support among rural adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007, 39 (4): 214-218.

Vue H, Reicks M: Individual and environmental influences on intake of calcium-rich food and beverages by young Hmong adolescent girls. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007, 39 (5): 264-272.

Bryant MJ, Ward DS, Hales D, Vaughn A, Tabak RG, Stevens J: Reliability and validity of the Healthy Home Survey: A tool to measure factors within homes hypothesized to relate to overweight in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008, 5 (1): 23.

Burgess-Champoux TL, Rosen R, Marquart L, Reicks M: The development of psychosocial measures for whole-grain intake among children and their parents. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (4): 714-717.

Byrd-Bredbenner C, Abbot JM, Cussler E: Mothers of young children cluster into 4 groups based on psychographic food decision influencers. Nutr Res. 2008, 28 (8): 506-516.

Faith MS, Storey M, Kral TV, Pietrobelli A: The feeding demands questionnaire: assessment of parental demand cognitions concerning parent-child feeding relations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (4): 624-630.

Fulkerson JA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Rydell S: Family meals: perceptions of benefits and challenges among parents of 8- to 10-year-old children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008, 108 (4): 706-709.

Gattshall ML, Shoup JA, Marshall JA, Crane LA, Estabrooks PA: Validation of a survey instrument to assess home environments for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008, 5: 3.

Haerens L, Craeynest M, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I: The contribution of psychosocial and home environmental factors in explaining eating behaviours in adolescents. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008, 62 (1): 51-59.

Haire-Joshu D, Elliott MB, Caito NM, Hessler K, Nanney MS, Hale N, Boehmer TK, Kreuter M, Brownson RC: High 5 for Kids: The impact of a home visiting program on fruit and vegetable intake of parents and their preschool children. Prev Med. 2008, 47 (1): 77-82.

Kroller K, Warschburger P: Associations between maternal feeding style and food intake of children with a higher risk for overweight. Appetite. 2008, 51 (1): 166-172.

Spurrier NJ, Magarey AA, Golley R, Curnow F, Sawyer MG: Relationships between the home environment and physical activity and dietary patterns of preschool children: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008, 5 (1): 31.

Hendy HM, Williams KE, Camise TS, Eckman N, Hedemann A: The Parent Mealtime Action Scale (PMAS): development and association with children's diet and weight. Appetite. 2009, 52 (2): 328-339.

Joyce JL, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ: Parent feeding restriction and child weight. The mediating role of child disinhibited eating and the moderating role of the parenting context. Appetite. 2009, 52 (3): 726-734.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Haines J, Robinson-O’Brien R, Hannan PJ, Robins M, Morris B, Petrich CA: Ready. Set. Action! a theater-based obesity prevention program for children: a feasibility study. Health Educ Res. 2009, 24 (3): 407-420.

Pearson N, Timperio A, Salmon J, Crawford D, Biddle SJ: Family influences on children’s physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009, 6: 34.

Corsini N, Wilson C, Kettler L, Danthiir V: Development and preliminary validation of the Toddler Snack Food Feeding Questionnaire. Appetite. 2010, 54 (3): 570-578.

Dave JM, Evans AE, Pfeiffer KA, Watkins KW, Saunders RP: Correlates of availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables in homes of low-income Hispanic families. Health Educ Res. 2010, 25 (1): 97-108.

MacFarlane A, Crawford D, Worsley A: Associations between parental concern for adolescent weight and the home food environment and dietary intake. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010, 42 (3): 152-160.

McCurdy K, Gorman KS: Measuring family food environments in diverse families with young children. Appetite. 2010, 54 (3): 615-618.

O’Connor TM, Hughes SO, Watson KB, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA, Fisher JO, Beltran A, Baranowski JC, Qu H, Shewchuk RM: Parenting practices are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13 (1): 91-101.

Tremblay L, Rinaldi CM: The prediction of preschool children’s weight from family environment factors: gender-linked differences. Eat Behav. 2010, 11 (4): 266-275.

Zeinstra GG, Koelen MA, Kok FJ, van der Laan N, de Graaf C: Parental child-feeding strategies in relation to Dutch children’s fruit and vegetable intake. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13 (6): 787-796.

Berlin KS, Davies WH, Silverman AH, Rudolph CD: Assessing family-based feeding strategies, strengths, and mealtime structure with the Feeding Strategies Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011, 36 (5): 586-595.

Byrd-Bredbenner C, Abbot JM, Cussler E: Relationship of social cognitive theory concepts to mothers’ dietary intake and BMI. Matern Child Nutr. 2011, 7 (3): 241-252.

McIntosh A, Kubena KS, Tolle G, Dean W, Kim MJ, Jan JS, Anding J: Determinants of children’s use of and time spent in fast-food and full-service restaurants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011, 43 (3): 142-149.

Moreno JP, Kelley ML, Landry DN, Paasch V, Terlecki MA, Johnston CA, Foreyt JP: Development and validation of the Family Health Behavior Scale. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011, 6 (2-2): e480-e486.

Murashima M, Hoerr SL, Hughes SO, Kaplowitz S: Confirmatory factor analysis of a questionnaire measuring control in parental feeding practices in mothers of Head Start children. Appetite. 2011, 56 (3): 594-601.

Murashima M, Hoerr SL, Hughes SO, Kaplowitz SA: Feeding behaviors of low-income mothers: directive control relates to a lower BMI in children, and a nondirective control relates to a healthier diet in preschoolers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012, 95 (5): 1031-1037.

Stifter CA, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch LL, Voegtline K: Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status. An exploratory study. Appetite. 2011, 57 (3): 693-699.

Anderson SE, Must A, Curtin C, Bandini LG: Meals in Our Household: reliability and initial validation of a questionnaire to assess child mealtime behaviors and family mealtime environments. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012, 112 (2): 276-284.

Dave JM, Evans AE, Condrasky MD, Williams JE: Parent-reported social support for child’s fruit and vegetable intake: validity of measures. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012, 44 (2): 132-139.

Moore LC, Harris CV, Bradlyn AS: Exploring the relationship between parental concern and the management of childhood obesity. Matern Child Health J. 2012, 16 (4): 902-908.

Rigal N, Chabanet C, Issanchou S, Monnery-Patris S: Links between maternal feeding practices and children's eating difficulties: validation of French tools. Appetite. 2012, 58 (2): 629-637.

Bandura A: Self-Efficacy: the Exercise of Control. 1997, New York: W.H. Freeman and Co

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K: An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988, 15 (4): 351-377.

Stokols D: Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol. 1992, 47 (1): 6-22.

Bandura A: Social learning theory. 1977, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Baumrind D: Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol Monograph. 1971, 4 (1, Part 2): 1-103.

Baumrind D: Rearing competent children. Child development today and tomorrow. Edited by: Damon W. 1989, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 349-378.

Maccoby E, Martin JA: Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development. Volume 4. Edited by: Hetherington E. 1983, New York: John Wiley, 1-101.

Costanzo P, Woody E: Domain-specific parenting styles and their impact on the child’s development of particular deviance: the example of obesity proneness. J Soc Clin Psych. 1985, 3: 425-445.

Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S: Individual and Environmental Influences on Adolescent Eating Behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002, 102 (3): S40-S51.

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of a projected funded by the National Cancer Institute (R21CA134986). Additional support was received through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL091093). The work was done at the UNC Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, a member of the Prevention Research Centers Program of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (#U48-DP000059). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. In addition to these sponsors, we would like to recognize the efforts of Dr. Robert DeVellis who provided feedback and guidance regarding the development of our quality assessment protocol. We would also like to thank Gracey Uffman, a graduate student in the Department of Maternal and Child Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, for her assistance with compiled responses for the quality assessment and entering data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the design, acquisition of data, and summarization of findings, and all have been involved in writing of the manuscript and given final approval of the version to be published. AV performed the original search and compiled the database of articles. AV, RT and MB reviewed titles and abstracts, and AV and RT applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to narrow the remaining pool. AV, RT, MB and DW all participated in the review of final articles, development of the quality assessment protocol, and use of this protocol to evaluate each instrument identified. AV summarized results and discussed findings with RT, MB and DW to develop structure for paper and tables and identify key messages for the discussion. All authors participated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaughn, A.E., Tabak, R.G., Bryant, M.J. et al. Measuring parent food practices: a systematic review of existing measures and examination of instruments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10, 61 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-61

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-61