Abstract

Background

Consensus Conferences and Guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis have been published, which recommend the use of prophylactic heparins in patients with risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The aim of this study was the assessment of the prophylaxis of VTE and the adherence to accepted guideline recommendations throughout the hospital.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out in a teaching hospital after guidelines were implemented. Patients' risk factors of deep vein thrombosis, risk categories of patients, and prophylaxis used in different wards were recorded. Appropriate adherence to the guidelines was analysed.

Results

Of 397 patients, prophylaxis was used in 231 patients (58%), and low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) were used in 224 of them (97%). Patients with prophylaxis had a higher mean number of risk factors (SD) than those without prophylaxis [3.1 (1.4) vs 1.9 (1.4); p < 0.05)]. Prophylaxis was used in 72% and 90% of moderate and high-risk patients respectively. Appropriate adherence to all guideline recommendations was observed in 42% of patients. Adherence to guidelines was high as regards the use of prophylaxis according to patients' risk factors (78%) and the use of appropriate types of prophylaxis (99%), but was low regarding appropriate heparin dosage (47%) and preoperative dosage (37%). Appropriate prophylaxis use was higher in critical care and surgical wards than in medical wards.

Conclusion

Prophylaxis of VTE is generally used in risk patients, but appropriate adherence to guidelines is less frequent and variable among different wards. Continuing medical education, discussion and dissemination of guidelines, and regular clinical audit are necessary to improve prophylaxis of VTE in clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Several clinical trials and meta-analysis have showed efficacy and safety of prophylaxis with non-fractionated and fractionated heparins for preventing VTE [1–10]. In addition to this, Consensus Conferences and Guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis have been published, which recommend the use of prophylactic heparins in patients at risk of venous thrombosis [11–14]. In spite of this scientific evidence, several studies have shown underuse of prophylaxis [15–18]. Previous studies carried out in our hospital on the use of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis showed poor adherence to accepted recommendations [16, 19]. The main problem was low use of prophylaxis in moderate/high risk patients. Subsequently, a guideline was elaborated in our institution, based on mentioned recommendations and disseminated through multifaceted intervention. Few studies have assessed the use of the thromboprophylaxis after implementing guidelines and differences among different wards in hospitals. The aims of the study were the assessment of the use of the prophylaxis of VTE throughout the hospital after implementation and dissemination of the guideline; and the assessment of the adherence to recommendations of the guidelines in the whole hospital and in different wards.

Methods

A cross-sectional study throughout a teaching hospital was carried out in 1999, four years after the institutional guideline was disseminated. A working group developed the guideline for preventing VTE in a two-stage process. Initially, an ad hoc institutional working group with members of the different parties concerned (i.e., haematologists, clinical pharmacologists, surgeons, other clinical specialists, and nurses) reviewed current practice as well as accepted scientific standards, and produced specific guidelines. The recommendations were based on widely accepted guidelines (table 1) [11, 12]. Afterwards, an attractive, pocket-size booklet was edited, which was presented, discussed and distributed to all nurses' shifts and physicians at specially convened meetings. In addition, during the following four years the booklet was also distributed to all junior physicians that were doing postgraduate training programs at the centre.

All patients admitted to the General Area of the hospital were selected for inclusion in the study. Patients from Maternity and Paediatric Area, and Traumatology-Orthopaedics Area were not included, and therefore children, obstetrical and gynaecological patients, orthopaedic and traumatology patients were not included in our study as such areas are located in different premises and separately managed in our institution. In addition, patients who might require anticoagulant treatment for medical reasons (venous thromboembolic disease, peripheral arterial disease, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation and prosthesic heart valves) were also excluded. Physicians trained for data extraction reviewed all medical records and nurse sheets. Information about demographic characteristics of patients, patients' risk factors of deep vein thrombosis, type of prophylaxis used, contraindications for using anticoagulants, the ward where the patient was admitted, and adherence to the guideline's recommendations were recorded. A specific committee ensured that all patients were correctly screened before being included in the study and decided the allocation of the patients to one of the risk groups. The patient could be admitted to the following wards: medical wards (internal medicine and other medical specialities), surgical wards (general surgery and other surgical specialities), critical care units, and emergency department. According to guideline recommendations patients were classified in three risk categories: low, moderate and high, and the risk scoring was a part of guideline implementation. Recommendations of guidelines were: a) early physical activity without other prophylaxis, such as heparins, in low risk patients; b) prophylaxis with low LMWH dose in moderate risk patients (or physical measures in patients with contraindications for the use heparins or acetylsalicylic acid in specific cases); and c) prophylaxis with higher LMWH dose in high risk patients (or physical measures in patients with contraindications for the use of heparins or acetylsalicylic acid in specific cases).

Appropriate adherence to the guidelines was assessed. The following indicators of adherence to guideline recommendations were analysed:

1) The proportion of patients receiving appropriate prophylaxis according to patients' risk category (no prophylaxis in low-risk patient and prophylaxis in moderate and high-risk patients);

2) The proportion of appropriate types of prophylaxis in moderate and high-risk patients (heparins in patients without contraindications and physical measures in patients with contraindications);

3) The proportion of appropriate dosage of heparins in moderate (low prophylactic dosage) and high-risk patients (high prophylactic dosage);

4) The proportion of preoperative dose used in surgical patients;

Data was analysed with SPSS/PC statistical software package. Statistical analysis was performed using Pearson χ2 test or test for trends to compare proportions and ANOVA to compare means. A 5 per cent level of significance was accepted for all statistical tests.

Results

Of 582 patients admitted to the hospital, 397 patients were included (figure 1), of which 166 (42%) were hospitalised in medical wards, 155 (39%) in surgical wards, 44 (11%) in critical care units, and 32 (8%) in the emergency department. The mean age (SD) of patients was 60 (17) years old [median age 64; range 15 – 92] and 229 patients (58%) were men. The majority of patients had risk factors of deep vein thrombosis [mean (SD) 2.6 (1.5); median 2, range 0–8], thus 302 (76%) had two or more risk factors, and 190 (48%) had three or more. The most frequent risk factors were age ≥ 40 years (335; 84%), surgery 148 (37%), immobilisation (145; 36.5%), cancer (128; 32%), obesity (61; 15%) and heart failure (24; 6%). According to guideline's assessment of risk, 297 patients (75%) were classified as having moderate or high risk. A relationship was observed between the number of risk factors and risk categories according to guidelines on the basis of the guideline specifications. The mean number of risk factors (SD) was 1 (0.7) in low-risk patients, 2.9 (1.2) in moderate-risk patients, and 4.1 (1.1) in high risk patients (F = 150.8; p < 0.0001).

Prophylaxis of venous thrombosis was used in 231 patients (58%). Pharmacological prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) was applied to 224 patients (97%) and with non-fractionated heparin (NFH) to only one patient (0.5%). Non pharmacological prophylaxis with elastic stockings was utilised in 6 patients (2.5%). Only 42 patients (11%) had some contraindication, absolute or relative, concerning the use of heparins (21 active haemorrhage, 9 conditions that may lead to bleeding, such as an active peptic ulcer or hepatic injury, 8 haemorrhagic stroke, 2 severe coagulopathy and 2 hypersensitivity to heparins). Of 166 patients without prophylaxis only 31 (19%) had some contraindication for the use of heparins.

Patients in whom prophylaxis was used had a higher mean number (SD) of risk factors than patients without prophylaxis [3.1 (1.4) vs. 1.9 (1.4); p < 0.05)]. The higher the patients' number of risk factors, the more often prophylaxis was used (table 2). Prophylaxis was used in the majority of moderate and high-risk patients (71.6% and 90% respectively). Of 77 moderate and high-risk patients who did not receive prophylaxis, only 14 (18%) had some contraindication for the use of heparins. Table 3 shows characteristics of the patients and prophylaxis in different risk categories established in guidelines. Prophylaxis was used in 81% (120) of patients undergoing surgery (148), 90% in moderate-risk and 91% in high-risk patients. Table 4 shows characteristics of patients according to risk factors and use of prophylaxis of VTE in different wards; the results varied widely between different wards.

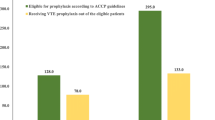

Adherence to all guideline recommendations only was observed in 167 patients (42%). Figure 2 shows appropriate adherence to guidelines according to patients' risk factors. Adherence to guidelines was high in relation to the prophylaxis use (308 of 397 patients; 77.6% appropriate) and the type of prophylaxis (217 of 220; 98.6 % appropriate), but was low with regard to heparin dosage (101 of 213; 47% appropriate) and preoperative dosage (55 of 148; 37% appropriate). Appropriate prophylaxis use was higher in surgical (85.2%) and critical care (90.9%) wards than in emergency (62.5%) and medical (69.9%) wards.

Discussion

The study explores the gap between practice and available knowledge or evidence and shows a high use of VTE prophylaxis (two out of every three hospitalised patients). The adherence to guideline recommendations regarding indications according to risk level and type of prophylaxis used was also high. Our results coincide with a French study, which assessed the adequacy of prophylaxis in surgical patients and compared it with generally accepted published guidelines [20]. However, our results also suggest that there may be overuse in low-risk patients (12%) and some underuse in moderate and high-risk patients (25%). It is interesting to note that most studies point out, as could be expected, to underutilisation of prophylaxis in high-risk patients [15, 16]; but there are no studies indicating the problem of overuse. In addition, the adherence was low regarding dose levels and the use of a preoperative dose. Similarly, George et al [21] also noticed that most protocol violations in routine surgical practice consisted of starting subcutaneous heparins postoperatively. Another finding to be commented on is the variability of the utilisation of VTE prophylaxis among different wards. Adherence was particularly high in critical care and surgery wards and lesser in medical wards and emergency units. A wide variability in the use of VTE prophylaxis between different wards has already been identified in other studies [17, 20, 22–24]. One of the conclusions arising from these results is that more educational efforts should be made to improve adherence to all guideline recommendations and throughout the hospital.

Our main results are similar to other studies in which the proportion of patients who received effective methods of prophylaxis also increased after educational interventions, such as guidelines [25, 26]. We had previously documented an underuse of VTE prophylaxis before the institutional guideline was available [16, 19] and an increased use of VTE prophylaxis two years after its implementation (unpublished data). A trend towards greater use of VTE prophylaxis is apparent during a ten-year period (table 5). Dissemination of guidelines may have played a role in improving prophylaxis use, but this could be related to many other factors. In addition, the degree of improvement with guidelines can be largely influenced by the methods used in its development, dissemination and implementation. The guidelines seems to be quite effective when its development is internal, the dissemination is undertaken through specific educational intervention and the implementation is via patient-specific reminder at the time of consultation [27, 28]. Thus, for instance, the publication of the Fourth ACCP Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy [12] alone was insufficient to change routine practice in prevention of VTE in a study that included several American hospitals [23]. In contrast, in a study performed in various short-stay hospitals a formal continuing medical education program significantly increased the frequency of prophylaxis for VTE [25]. However, even after those interventions, prophylaxis for VTE remained underutilised, suggesting that other types of interventions should be developed [25]. In addition to this, other factors may also be related to increasing use of prophylaxis, because this has been observed even in control groups in hospitals without any guideline implementation [25]. One of these factors may be the introduction of new drugs and their promotion by pharmaceutical companies. Specifically in the field of VTE prophylaxis, at the beginning of the nineties, a new type of heparins, fractionated heparin or LMWH, was introduced. So, variations in thromboprophylaxis may be due to different factors such as the clinical guideline implementation, the introduction and promotion of LMWH, as well as general awareness among physicians over time.

Our study has several important limitations. First of all, we did not include a control group in order to determine the real effect of guideline; so, we can not exclude the effect of confounding factors mentioned above. In addition, we can not establish the external validity of our results, because our hospital is a tertiary teaching hospital with typical and non-typical patients, and with expertise staff that is non-representative of those throughout the country.; so we do not know whether these results are similar in other hospitals. A key issue is the validity of guideline used as a reference of the evidence for assessing the practice. It has been argued that official guidelines are hardly ever evidence-based because the input of expert groups is above minimum and the long delay between arising new data and guideline completion or updating. Nevertheless, the guidelines were based on the best possible evidence, and the main recommendations of guidelines, for instance appropriate prophylaxis use in moderate and high-risk patients, have clearly showed themselves to be effective [1–10] and efficient [29–32].

Conclusions

Prophylaxis of VTE is generally used in risk patients, but appropriate adherence to guidelines is less frequent and variable among different wards. There is room for improvement and more efforts need to be made in order to better disseminate and implement the guidelines' recommendations throughout the hospital and to reduce variability in daily practice decision making. Appropriate corrective measures to improve prophylaxis of VTE may be continuing medical education with discussion and consensus with physicians, dissemination of guidelines with relevant information and regular clinical audit as feedback on prescribing patterns for groups of physicians.

References

Colditz GA, Tuden RL, Oster G: Rates of venous thrombosis after general surgery: combined results of randomised clinical trials. Lancet 1986, 2: 143-146. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91955-0

Collins R, Scrimgeour A, Yusuf S, Peto R: Reduction in fatal pulmonary embolism and venous thrombosis by perioperative administration of subcutaneous heparin. Overview of results of randomized trials in general, orthopedic and urological surgery. N Engl J Med 1988, 318: 1162-1173.

Claggett GP, Reisch JS: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgical patients. Results of meta-analysis. Ann Surg 1988, 208: 227-240.

Nurmohamed MB, Rosendaal FR, Büller HR, Dekker E, Hommes DW, Vandebroucke JP, Briet E: Low molecular weight heparin versus standard heparin in general surgery and orthopedic surgery: a meta-analysis. Lancet 1992, 340: 152-156. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93223-A

Leizorovicz A, Haugh MC, Chapuis FR, Samama MM, Boissel JP: Low molecular weight heparin in prevention of perioperative thrombosis. BMJ 1992, 305: 913-920.

Imperiale TF, Speroff TA: Meta-analysis of methods to prevent venous thromboembolism following total hip replacement. JAMA 1994, 271: 1780-1785. 10.1001/jama.271.22.1780

Mismetti P, Laporte-Simitsidis S, Tardy B, Cucherat M, Buchmuller A, Juillard-Delsart D, Decousus H: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in internal medicine with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparins: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Thromb Haemost 2000, 83: 14-19.

Iorio A, Agnelli G: Low-molecular-weight and unfractionated heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in neurosurgery: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160: 2327-2332. 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2327

Brookenthal KR, Freedman KB, Lotke PA, Fitzgerald RH, Lonner JH: A meta-analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2001, 16: 293-300. 10.1054/arth.2001.21499

Koch A, Ziegler S, Breitschwerdt H, Victor N: Low molecular weight heparin and unfractionated heparin in thrombosis prophylaxis: meta-analysis based on original patient data. Thromb Res 2001, 102: 295-309. 10.1016/S0049-3848(01)00251-1

Thromboembolic Risk Factors (THRIFT) Consensus Group: Risk of and prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in hospital patients. BMJ 1992, 305: 567-574.

Clagett GP, Anderson Jr FA, Heit J, Levine MN, Wheeler HB: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 1995, 108(4 Suppl):312S-334S.

Clagett GP, Anderson Jr FA, Heit JA, Knudson M, Lieberman Jr, Merli GJ, Wheeler HB, Geets W: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 1998, 114(5 Suppl):531S-560S.

Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA Jr, Wheeler HB: Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 2001, 119(Suppl 1):132-175. 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.132S

Anderson FA, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan A: Physician practices in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 1991, 115: 591-595.

Vallès JA, Vallano A, Torres F, Arnau JM, Laporte JR: Multicentre hospital drug utilization study on the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1994, 37: 255-259.

Keane MG, Ingenito EP, Goldhaber SZ: Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the medical intensive care unit. Chest 1994, 106: 13-14.

Braztzler DW, Raskob GE, Murray CK, Bumpus LJ, Piatt DS: Underuse of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for general surgery patients. Arch Intern Med 1998, 158: 1909-1912. 10.1001/archinte.158.17.1909

Vallano A, Vallès JA, Gracia RM, Arnau JM, Duran S, Laporte JR: Use of heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1994, 3: 211-214.

Lepaux DJ, Charpentier C, Pertek JP, Pinelli C, Delagoutte JP, Delorme N, Hoffman M, Lecompte T, Nace L, Voltz C, Wahl D, Briancon S: Assessment of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in surgical patients: a study conducted at Nancy University Hospital, France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1998, 54: 671-676. 10.1007/s002280050533

George BD, Cook TA, Franlin IJ, Nethercliff J, Galland RB: Protocol violation in deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1998, 80: 55-57.

Egermayer P, Robins C, Town GI: Survey of the use of thromboprophylaxis for medical patients at Christchurch Hospital. N Z Med J 1999, 112: 246-248.

Stratton MA, Anderson FA, Bussey HI, Caprini J, Comerota A, Haines ST, Hawkins DW, O'Connell MB, Smith RC, Stringer KA: Prevention of venous Thromboembolism. Adherence to the 1995 American College of Chest Physicians Consensus Guidelines for surgical patients. Arch Intern Med 2000, 160: 334-340. 10.1001/archinte.160.3.334

Riskpam RP, Trottier SJ: Utilization of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in a medical-surgical ICU. Chest 1998, 113: 162-164.

Anderson FA, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Forcier A, Patwardhan A: Changing clinical practice. Prospective study of the impact of continuing medical education and quality assurance programs on use of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism. Arch Intern Med 1994, 154: 669-677. 10.1001/archinte.154.6.669

McEleney P, Bowie P, Robins JB, Brown RC: Getting a validated guideline into local practice: implementation and audit of the SIGN guideline on the prevention of deep thrombosis in a district general hospital. Scott Med J 1998, 43: 23-25.

Grimshaw JM, Russell IT: Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet 1993, 342: 1317-1322. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92244-N

Byrne GJ, McCarthy MJ, Silverman SH: Improving uptake of prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in general surgical patients using prospective audit. BMJ 1996, 313: 917.

Hull RD, Hirsh J, Sackett DL, Stoddart GL: Cost-effectiveness of primary and secondary prevention of fatal pulmonary embolism in high-risk surgical patients. Can Med Assoc J 1982, 127: 990-995.

Szucs TD, Schramm W: The cost-effectiveness of low-molecular-weight heparin vs unfractionated heparin in general and orthopaedic surgery: an analysis for the German healthcare system. Pharmacol Res 1999, 40: 83-89. 10.1006/phrs.1999.0479

Matzsch T: Thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin: economic considerations. Haemostasis 2000, 30(Suppl 2):141-145.

Bell GK, Goldhaber SZ: Cost implications of low molecular weight heparins as prophylaxis following total hip and knee replacement. Vasc Med 2001, 6: 23-29. 10.1191/135886301670156965

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

VA, participated in the design of the study, its coordination, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript.

AM, participated in the design of the study, its coordination and helped in writing the manuscript.

PMiralda G, conceived of study, and participated in the design of the study.

PJ, participated in the design of the study.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Vallano, A., Arnau, J.M., Miralda, G.P. et al. Use of venous thromboprophylaxis and adherence to guideline recommendations: a cross-sectional study. Thrombosis J 2, 3 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-9560-2-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-9560-2-3